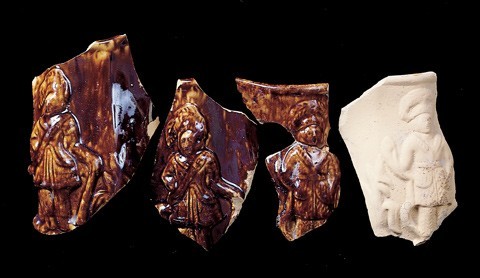

Sherds, Clinton Street Pottery, Trenton, New Jersey, 1863–1868. Rockingham-type ware. (All photos, Gavin Ashworth.) These sherds are from small pitchers with a molded plumed cavalier on opposing sides.

Sherds, Clinton Street Pottery, Trenton, New Jersey, 1863–1868. Rockingham-type ware. Sherds from a teapot with a molded scene of two ladies having tea.

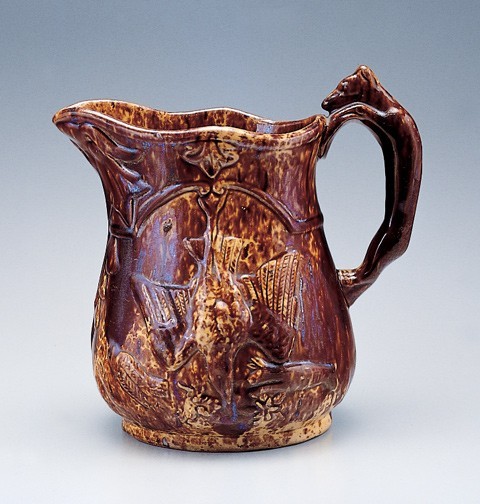

Sherds, Clinton Street Pottery, Trenton, New Jersey, 1863–1868. Rockingham-type ware. These fragments are from a hound-handled hunt scene pitcher depicting a running stag and a hanging game bird around the body over a small standing bird and a running rabbit near the base.

Pitcher, Clinton Street Pottery, Trenton, New Jersey, 1863–1868. Rockingham-type ware. H. 10". (William B. Liebeknecht collection.) An antique example of a Rockingham glazed hound-handled hunt scene pitcher. Note the eagle head that forms the spout.

Sherds, Clinton Street Pottery, Trenton, New Jersey, 1863–1868. Biscuit fired earthenware from a small Toby pitcher with a scowling face.

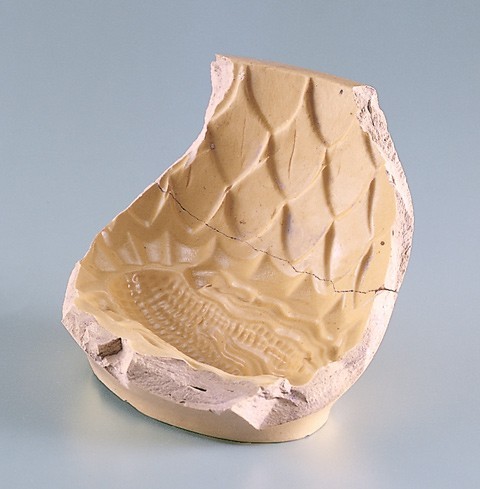

Sherds, Clinton Street Pottery, Trenton, New Jersey, 1863–1868. Yellow ware. A yellow ware corncob food mold fragment with overlapping scaled sides.

In September 2000, archaeological monitoring conducted by Hunter Research, Inc. prior to the construction of the recently opened Marriott Hotel in downtown Trenton, New Jersey, included sampling of a waster deposit of plain yellow ware, Rockingham ware, and related kiln furniture.[1] The deposit, observed in the side of a construction trench, was roughly twenty feet in length and up to two and half feet thick, and consisted of a densely packed lens of several thousand sherds and kiln fragments. Analysis of these materials and of the land use history of the hotel site has enabled the assemblage to be attributed to Charles Coxon’s Clinton Street Pottery and assigned a manufacturing date between 1863 and 1868.[2]

Several vessel forms are represented in the assemblage, with the most common being shallow undecorated pie plates and nappies of various sizes. The majority of the sherds consist of plain yellow ware, but some pieces display distinctive relief-molded decoration. Approximately forty percent of the sherds have a clear alkaline glaze, with roughly half of this material being covered with the streaked or mottled brown manganese glaze that is characteristic of Rockingham ware. The remaining sherds are bisque-fired and show a range of yellow ware body types, most likely the result of multiple clay sources or impurities in the clay. No makers’ marks are in evidence, which is not surprising since “some 90% of all yellow ware is unmarked.”[3] Dating and attribution of this ware has long been the subject of frustrating speculation; in this instance, however, there is sufficient evidence to pinpoint both an approximate date and likely manufacturer.[4]

Dating of the waster deposit was accomplished in part through the archaeological stratigraphy and known history of the site. The lens containing the sherds and kiln furniture was sealed approximately one foot beneath a thick layer of flint nodules and chunks of quartz and feldspar, materials that derive from the use of the site by the Golding & Company flint and spar mill, a supplier of tempering materials to the Trenton potteries. The Golding Company was in operation at this location from 1868 until the late 1920s, thereby providing a terminus ante quem of 1868 for the waster deposit.[5]

Assignation of the ceramic materials in the waster deposit to Charles Coxon’s Clinton Street Pottery stems in part from the dating of the deposit, but is based primarily on the attributes of the sherds showing relief-molded decoration. Among the Rockingham ware motifs identified are: a cavalier figure, typically found on creamers (fig. 1); two ladies having tea, typically found on teapots (fig. 2); a hunt scene, found on handled pitchers where a stag and hanging bird are molded on the body and the handle is formed as an outstretched hound (figs. 3, 4); a small Toby pitcher (fig. 5); and a corn cob impression, found on food molds (fig. 6). Several Trenton pottery experts, among them Jay Lewis and the late David J. Goldberg, agree that these relief patterns are most likely the product of the Clinton Street Pottery. The clarity of the design and attention to detail suggest that the molds were probably the work of John Coxon, rather than his better-known father, Charles.

Charles Coxon founded the Clinton Street Pottery, a two-kiln facility, in 1863 in the Coalport section of Trenton. Coxon, a native of Longton, Staffordshire, immigrated to the United States in 1849, working first in the Bennett Pottery in Baltimore (1849–1858) and then the Swan Hill Pottery in South Amboy (1858–1861), before relocating to Trenton and working for the firms of Millington & Astbury and William Young & Sons. In the year following the establishment of the Clinton Street Pottery, John S. Thompson joined with Coxon to form the company “Coxon & Thompson,” and the firm began concentrating on the manufacture of “creamware and white graniteware.” Yellow ware and Rockingham ware were likely also being produced during these early years, as this is the material for which Charles Coxon is best known. Coxon died of sunstroke in July of 1868, but his widow and sons reorganized the pottery under the name Coxon and Company. This firm thrived in the production of hotel china until 1883 when it was sold to the firm of Alpaugh and McGowan. The pottery was eventually renamed the Empire Pottery and in 1900 became absorbed by the Trenton Potteries Company.[6]

The identification of the yellow ware and Rockingham ware materials from the Marriott Hotel site as products of Charles Coxon’s Clinton Street Pottery in the mid-1860s supplies a useful benchmark for ceramic historians, collectors, and archaeologists. This find demonstrates the value of documenting and analyzing ceramic waste deposits in major industrial pottery centers, even when these are located some distance from the manufacturing site.

William B. Liebeknecht

Principal Archaeologist

Hunter Research, Inc.

<wbl@hunterresearch.com>

Rebecca White

Archaeologist

Hunter Research

Laboratory Supervisor

<rwhite@hunterresearch.com>

Richard W. Hunter, Ph.D.

President and Principal Archaeologist

Hunter Research, Inc.

<rwhunter@hunterresearch.com>

<http://hunterresearch.com>

An initial archaeological study of the Marriott Hotel site was completed in 1998. See Hunter Research, Inc., “Phase I Archaeological Investigation, Proposed Marriott Hotel Conference Center, City of Trenton, Mercer County, New Jersey” (report on file, New Jersey Historic Preservation Office, Trenton, 1998). An expanded article on the Coxon waster deposit is to appear in Trenton Potteries, the Newsletter of the Potteries of Trenton Society, Volume 3, Issues 1 and 2. A full report on all aspects of the archaeological monitoring at the Marriott Hotel site, including a detailed inventory of the Coxon ceramic waste, is forthcoming in 2003.

In the case of this deposit, waste was carted just over a mile from the Coxon kilns down to the mouth of Assunpink Creek on the Delaware River, where it was used as fill. Much of the Delaware River shoreline below Assunpink Creek, especially in Lamberton, is composed of similar waste from a range of Trenton’s industrial potteries.

Joan Leibowitz, Yellow Ware: The Transitional Ceramic (Clinton, Mass.: Colonial Press, Inc., 1985), p. 9.

John Spargo, Early American Pottery and China (New York, N.Y.: Garden City Publishing Company, 1926), pp. 196–97.

Trenton Historical Society, A History of Trenton, 1679–1929: Two Hundred and Fifty Years of a Notable Town with Links in Four Centuries (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1929), pp. 920, 955; “Golding Sons Company Build New Feldspar Mill,” Trenton Magazine (September 1928): 2–3, 20.

For further detail on the Coxon family and their potteries, see Edwin Atlee Barber, “Early Ceramic Printing and Modeling in the United States,” Old China 3, no. 3 (1903): 51–52; David J. Goldberg, “Charles Coxon: Nineteenth-Century Potter, Modeler-Designer and Manufacturer,” Journal of the American Ceramic Circle 9 (1994), pp. 28–64; Hunter Research, Inc., “The Trenton Potteries Database” (Electronic Database, Property of New Jersey Department of Transportation, Trenton, 1999).