A group of hollow ware vessels, Staffordshire, 1720–1740. Slipware. (All objects courtesy, State Museum of Pennsylvania; photos, Gavin Ashworth.) A grouping of some of the ceramics recovered from the Market Street excavations. The candlestick fragment in the center is the only object not recovered from the well.

Double and single-handled cups, Staffordshire, 1720–1740. Slipware. These large drinking vessels were recovered from the Market Street well.

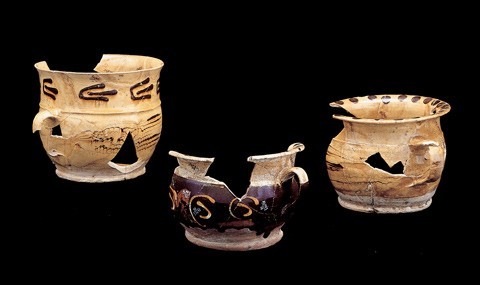

Two chamber pots, center and right, and a posset pot, left, Staffordshire, 1720–1740. Slipware. Posset pot H. 5 3/4".

Large cup, Staffordshire, 1720–1740. Slipware. H. 4". A striking slipware cup decorated on the exterior with brown slip below the rim, and in reverse on the bowl.

Dishes, Samuel Malkin, Burslem, Staffordshire, 1720–1740. Slipware. D. 6". These molded dishes are simply embellished with brown slip dots. They are sooted on the exterior, indicating they were used as cookware.

Detail of “S M” initials from a dish illustrated in fig. 5.

Sunface dish, probably Samuel Malkin, Burslem, Staffordshire, 1720–1740. Slipware. D. 11 1/8". The sooted exterior of this dish evidences its use in the oven

Sunface dish, probably Samuel Malkin, Burslem, Staffordshire, 1720–1740. Slipware. D. 7 1/2". This dish displays no evidence of oven use.

Fragments of other sunface dishes. Probably Burslem, Staffordshire, ca. 1720–1740. Slipware. These fragments, also from the Market Street well, are from sunface dishes most likely made by Samuel Malkin.

During the winter of 1976, Charles E. Hunter and Herbert W. Levy conducted archaeological excavations on historic sites located between Market and Church Streets and between Front and Second Streets in downtown Philadelphia to mitigate highway construction in the area.[1] Among the many colonial features excavated, a well on Market Street was one of the most significant. Sealed around 1760, it yielded a rich harvest of early eighteenth-century ceramics, including a remarkable assemblage of slipware vessels made in Staffordshire, England (figs. 1, 2).

Neither subtle nor especially ground breaking, this article is to inform readers about one small group from the vast collections of material unearthed during the seminal years of historical archaeology. Like Pompeii, where I have labored for almost forty years, Philadelphia possesses an immense collection of archaeological data that sorely needs description and further study.[2] As the Market Street slipware assemblage illustrates, the unreported ceramic heritage from our historic past is extremely significant and intrinsically exciting (figs. 3, 4).

Most notable among the slipware vessels in the Market Street assemblage are several dishes manufactured by Samuel Malkin (1688–1741) of Burslem in Staffordshire, England. Malkin’s distinctive relief-decorated and press-molded earthenware is well recognized.[3] He was one of the last important Staffordshire slipware potters to employ press molding, which by the end of the eighteenth century had declined there considerably.[4] In 1939, excavations of Malkin’s factory site in Burslem yielded a number of important fragments of his labors, including molds for making slipware. Among his many signed pieces are examples that display the initials “SM” in molded relief.

Two important small dishes from the Market Street assemblage parallel the examples recovered in Burslem. They carry the initials “SM” in relief flanking a central dot of slip decoration and four small crosses (figs. 5, 6). Also in the collection are two almost intact sunface dishes and sherds from two others (figs. 7, 8). It is believed that Malkin made these impressive large dishes.[5] Press-molded, they are emblazoned in relief with a sun’s radiating countenance, magnificently achieving the ancient Renaissance desire for “filling the tondo.” The fragmented sunface dishes are tantalizing because they are decorated much differently. For example, the possible eye sherd may belong to an undocumented sunface design (fig. 9).

All together, this remarkable collection brings to mind the familiar words of Henry Glassie, “Pottery works in the world. Displaying the complexity of the human condition, it brings the old and the new, the personal and the social, the mundane and transcendent into presence and connection.”[6] Archaeologically, its story awaits a full contextual examination of its provenience before its significance can be fully addressed.

For Philadelphia, with its own thriving earthenware factories in operation, this Staffordshire slipware assemblage raises a number of questions. For instance, what did these vessels mean to the Philadelphia consumers? Were they specially selected for their curious iconography? Did they have religious connotations, as did some signed Malkin dishes with biblical illusions that promoted a virtuous life? Did they carry political overtones, as did other Malkin examples that illustrated Jacobite political references? Or, were they simply the products of a flourishing Atlantic trade in which an enormous variety and quantity of pottery arrived regularly from the homeland?

Much historical archaeology has been carried out in the city of Philadelphia over the last half century.[7] Could more sunfaces or slipware with other messages and images still slumber in the relative oblivion of collections from these excavated sites? Future studies of these archaeological materials promise to lead us into new avenues of understanding and interpreting the social and economic history of Philadelphia and its surroundings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

First, kudos and a golden Marshalltown trowel are awarded to the excavators who, in 1976, with their accurate recording and interpretative drawings, helped put this material into the proper context. Second, the staff of the State Museum of Pennsylvania is thanked for its outstanding job in conserving this material and for graciously permitting its publication. Assistant curator Janet Johnson, ably assisted by Elizabeth Wagner and Rich Petyk, is to be warmly thanked not only for her cooperation with the author, but for her boundless enthusiasm for these objects as well. Janet is also acknowledged for mercifully encouraging me to fully analyze this feature in the future.

David G. Orr, Ph.D.

Senior Regional Archaeologist

Northeast Region, National Park Service

<DLORR44@msn.com>

Charles E. Hunter and Herbert W. Levy, “Report on the Archaeological Salvage Excavations on the Northwest Side of Market and Front Streets, Philadelphia, Pa. Winter, 1976” (report for the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, on file Pennsylvania State Museum, Harrisburg, Pa.). Herbert Levy, a graduate student at the American Civilization Department at the University of Pennsylvania, brought some of this material to my attention at that time while I was on the faculty. I attributed several of the objects to the StaVordshire potter Samuel Malkin, and used them in various unpublished works, including a paper I presented in the fall of 1999 on early archaeology in Philadelphia at “The Arts of Baroque Pennsylvania: a Symposium” sponsored by the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The assemblage is published for the first time in this journal.

A group called the Philadelphia Archaeological Forum was founded in Philadelphia recently. Among its goals is to provide support and funding for Philadelphia’s “orphan collections,” as well as those of the major institutions.

See especially Leslie B. Grigsby, The Longridge Collection of English Slipware and Delftware, 2 vols. (London: Jonathan Horne Publications, 2000), and Michelle Erickson and Robert Hunter, “Dots, Dashes, and Squiggles: Early English Slipware Technology,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001) pp. 94–114. The latter article provides an outstanding description of exactly how these decorative dishes were made and decorated.

David Barker, Slipware (Princes Risborough, Eng.: Shire Publications Ltd., 1989), p. 18

Other sunface dishes are known and most are attributed to Malkin. Michael Cooper illustrates one larger than figure 3 (13" in diameter), and another was discovered in the excavations at the Wetherburn Tavern site in Colonial Williamsburg. Ronald G. Cooper, English Slipware Dishes, 1650–1850 (London: Alec Tiranti, 1968), fig. 248. Leslie B. Grigsby, English Slip-Decorated Earthenware at Williamsburg (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1993), p. 44.

Henry Glassie, The Potter’s Art (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, and Philadelphia: Material Culture, 1999), p. 17.

John Cotter, Daniel G. Roberts, and Michael Parrington, The Buried Past: An Archaeological History of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992). See especially p. 470, where the authors state: “Conserving archaeological data and making them readily accessible are among other top priorities for future Philadelphia archaeology.”