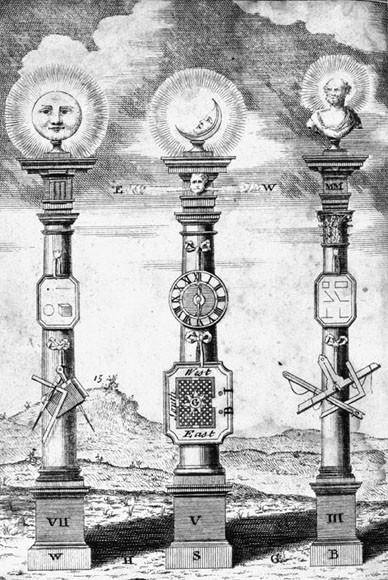

From Johann Martin Bernigeroth “Les Costumes des Francs-Macons dans leurs Assemblees,” ca. 1745. (By permission of the Board of General Purposes of the United Grand Lodge of England.) This rare French print depicts the Masonic third-degree ritual: the raising of the master Mason. Although the “teardrop” symbol is associated specifically with French Masonry, other elements are characteristic of the British ritual.

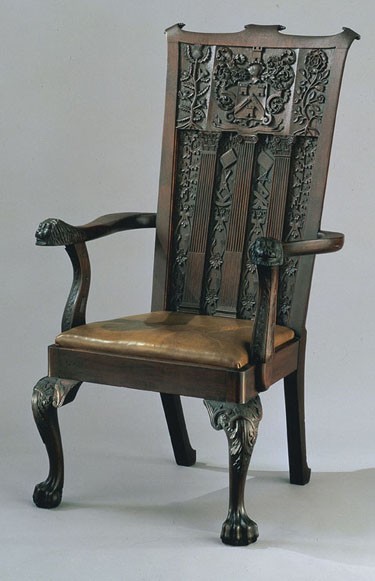

Masonic master’s chair by Benjamin Bucktrout, Williamsburg, Virginia, 1769–1775. Mahogany with walnut; painted and gilded ornament, original leather upholstery. H. 65 1/2", W. 31 1/4", D. 29 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Masonic master’s chair, Williamsburg Lodge No. 6, Williamsburg, Virginia, 1765–1770. Mahogany. H. 52 1/4", W. 29 1/2", D. 26 1/4". (Courtesy, Williamsburg Lodge No. 6, A.F. & A.M.; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Masonic master’s chair, Fredericksburg Lodge No. 4, Fredericksburg, Virginia, ca. 1775. Mahogany with walnut. H. 42 1/2", W. 27 1/2", D. 18 7/8". (Courtesy, Fredericksburg Lodge No. 4, A.F. & A.M; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) The Fredericksburg Lodge was chartered by the Grand Lodge of Scotland in 1758. The symbol of the sundial on this chair associates it with Scottish Freemasonry.

Masonic chair, Union Kilwinning Lodge No. 4, Charleston, South Carolina, ca. 1770. Mahogany; ash slip seat. H. 53 1/2", W. 27 1/2". (Collection of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) The painted square and compass cover an original inlaid plumb rule, indicating that this chair served the senior warden of the lodge.

Masonic master’s chair attributed to Richard Hall, Royal White Hart Lodge No. 2, Halifax, North Carolina, ca. 1765. Walnut; yellow pine slip seat. H. 48 9/16", W. 24", D. 17" (seat). (Courtesy, Royal White Hart Lodge No. 2, A.F. & A.M.; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Detail of the carved dolphin leg on the chair illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, Hans Lorenz.)

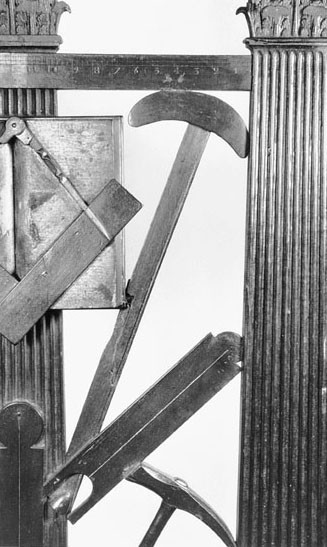

Detail of plate 21 in Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director, 1st ed. (London, 1754). (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Detail of the stamped signature and layout lines for the carving on the back of the Composite capital on the chair illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, F. C. Howlett.)

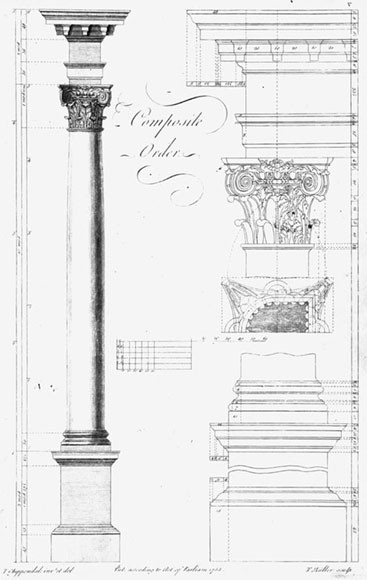

“Composite Order” from Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director, 1st ed. (London, 1754). (Courtsey, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

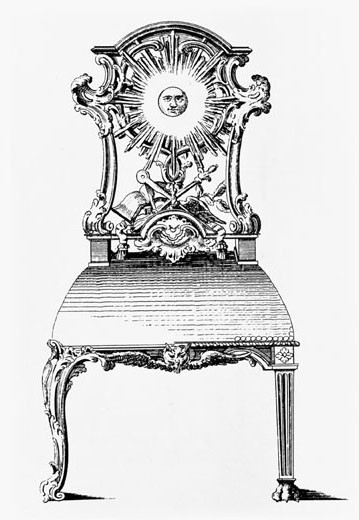

Masonic chair illustrated on plate 25 of Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director, 3d ed. (London, 1762).

Preconservation view of the chair illustrated in fig. 2, showing many of the symbolic elements missing or obscured by darkened varnish and overpaint. (Photo, Hans Lorenz.)

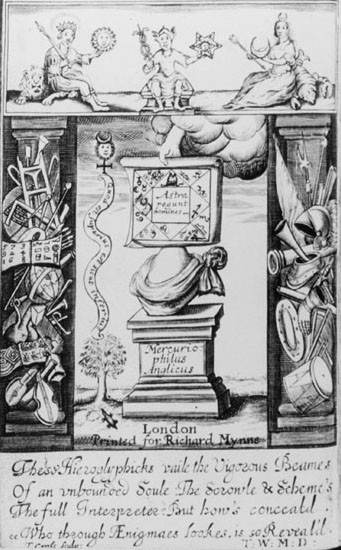

Frontis of James Hasolle, esq., Chymical Collections (London, 1650). (By permission of the Board of General Purposes of the United Grand Lodge of England.) The frontis of this seventeenth-century alchemical text has symbols later incorporated into speculative Masonry.

Frontis of James Anderson’s The Constitutions of the Freemasons (London: William Hunter and John Hooke, 1723). (By permission of the Board of General Purposes of the United Grand Lodge of England.) This was the first publication authorized by the newly formed (1717) Grand Lodge of England.

William Hogarth, Night, from the Times of Day series, London, 1738. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) Hogarth was a Freemason who nonetheless parodied the association of the Craft with late-night drunkenness.

Preconservation detail of the right capital of the chair illustrated in fig. 2, showing numerous losses and a poor repair mimicking the form of the missing upper portion. (Photo, F. C. Howlett.)

Detail of the right capital of the chair illustrated in fig. 2 during treatment, which included removal of old repairs, glue, and varnish from areas of loss prior to attaching replacements. (Photo, F. C. Howlett.)

Post-conservation detail of the right capital of the chair illustrated in fig. 2 with replacements carved and toned to match the adjacent surfaces. (Photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Frontis of Thomas and Batty Langley’s The Builder’s Jewel: or the Youth’s Instructor, and Workman’s Remembrancer (1741; reprint ed., London: R. Ware, 1754). (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Preconservation detail of the sun on the chair illustrated in fig. 2, showing degraded bronze paint obscuring earlier layers of gold leaf. (Photo, Hans Lorenz.)

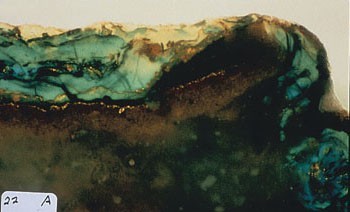

Cross-section of a sample taken from the sun (200x), viewed with a combination of visible light and near-ultraviolet light to reveal original gilding and restoration layers. (Photo, F. C. Howlett.)

22.1 Bronze paint (bronze powder in plant resin)

22.2 Bronze paint (bronze powder in plant resin)

22.3 Gold leaf

22.4 Oil size

22.5 Original gold leaf

22.6 Red bole

22.7 Gesso

Post-conservation detail of the sun on the chair illustrated in fig. 2, showing early oil gilding. (Photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Preconservation detail of the moon on the chair illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, F. C. Howlett.) Two coats of dark, degraded varnish are above the mahogany.

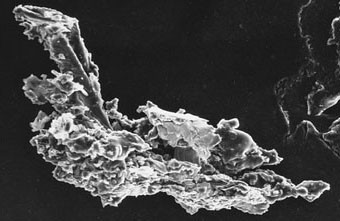

Scanning electron microscope photomicrograph of a particle taken beneath the moon’s lower lip (350x). (Courtesy, Smithsonian Center for Materials Research and Education, Smithsonian Institution; photo, Melanie Feather.)

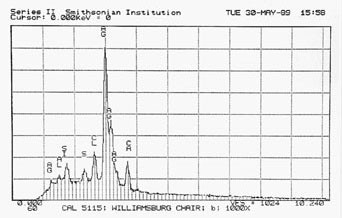

Scanning electron microscope–EDX spectrum indicating the presence of silver in the particle illustrated in FIg. 25. (Courtesy, Smithsonian Center for Materials Research and Education, Smithsonian Institution.)

Detail of the moon on the chair illustrated in fig. 2 during treatment, showing the application of new silver leaf above an acrylic barrier coating. (Photo, F. C. Howlett.)

Post-conservation detail of the moon on the chair illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Detail of the bust of the worshipful master on the chair illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, Hans Lorenz.)

X-radiograph of the bust illustrated in fig. 29. (Courtesy, Robert Berry, Fabrication Division, Nondestructive Evaluation Section, NASA—Langley Research Center.)

Josiah Wedgwood Factory, Bust of Matthew Prior, England, ca. 1775. Basalt stoneware. H. 9", W. 5". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Detail of the scroll on the keystone of the chair illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, F. C. Howlett.) The letters “VIR” began to appear during removal of the degraded bronze paint.

Post-conservation detail of the scroll illustrated in fig. 32. (Photo, Hans Lorenz.)

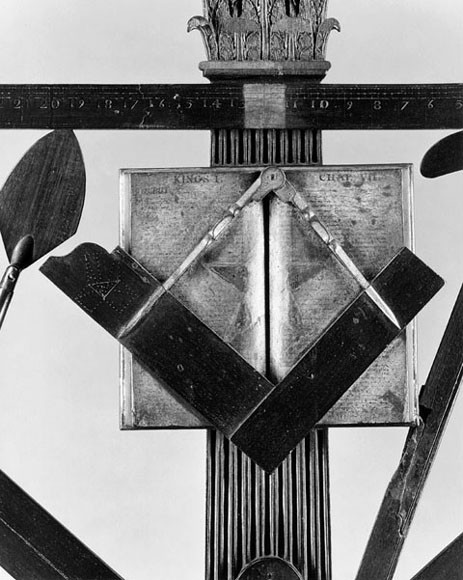

Preconservation detail of the three great lights on the chair illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Detail of the Bible during treatment, showing removal of the degraded varnish layers. (Photo, F. C. Howlett.)

Masonic apron presented by George Washington to General William Schuyler, ca. 1770. (Courtesy, Alexandria—Washington Lodge No. 22, A.F. & A.M.; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

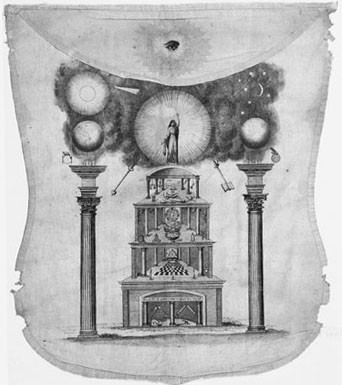

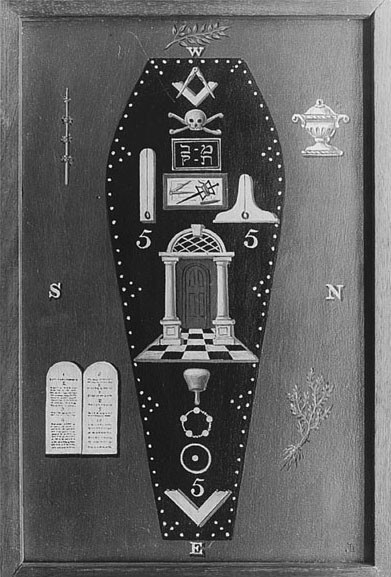

Floor cloth presented by Joseph Montfort to the Royal White Hart Lodge No. 2, Halifax, North Carolina, ca. 1765. (Courtesy, Royal White Hart Lodge No. 2, A.F. & A.M.; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

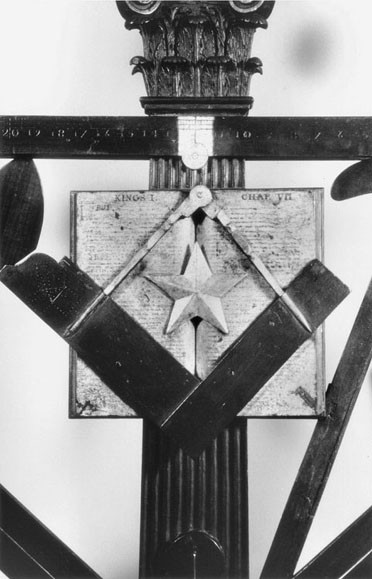

Post-conservation detail of the three great lights and the five-pointed star on the chair illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Grand master’s jewel, probably Williamsburg, Virginia, 1778. Silver gilt. H. 5 1/2", W. 6 1/4". (Courtesy, Grand Lodge of Virginia; photo, F. C. Howlett.) The jewel dates from the founding of the independent Grand Lodge of Virginia.

Detail of the replacement tool on the back of the chair illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, F. C. Howlett.) The tool probably dates from the late nineteenth century.

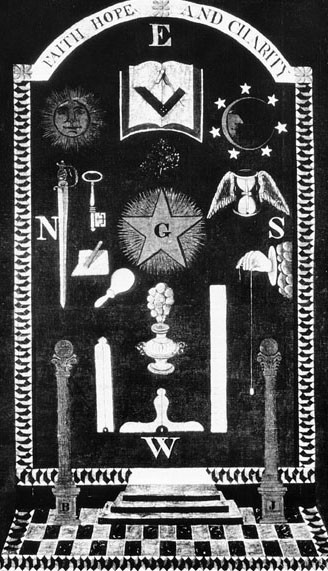

Third-degree tracing board by J. Bowring, Britain, 1819. Painted wood. (By permission of the Board of General Purposes, United Grand Lodge of England.) The English working tools of the master mason (compass, pencil, and skirret) appear in the rectangle above the arch.

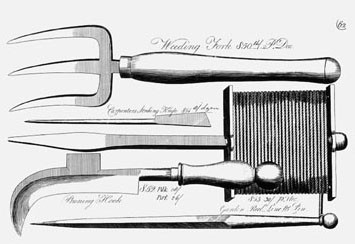

“Garden Reel” illustrated on pl. 62 of a Birmingham, England, tool catalogue, ca. 1798. (Courtesy, Peabody-Essex Museum.) In British Freemasonry, the tool described here as a “garden reel” is a version of the wooden “line” or “chalk line,” a tool given the name “skirret” by British Freemasons.

Detail of the cushion above the arch on the chair illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, F. C. Howlett.)

Detail of the crown and cushion in Allan Ramsay’s portrait of Queen Charlotte, ca. 1770. Oil on canvas. 96 7/8" x 61 3/8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

The Benjamin Bucktrout Masonic master’s chair, computer enhanced to illustrate speculations about the missing symbols. (Photography, Hans Lorenz; system work, GIST.)