Tea table attributed to William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1745–1755. Walnut. H. 29 5/8"; Diam. of top: 34 3/4". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; purchased with

the Haas Community Fund and the J. Stodgell Stokes Fund.)

Tea table, eastern Virginia, 1750–1770. Mahogany. H. 27 1/8"; Diam. of top: 32 3/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Joseph Highmore, Mr. B. Finds Pamela Writing, England, 1743–1744. Oil on canvas. 25 5/8" x 29 7/8". (Courtesy, Tate Gallery, London/Art Resource, N.Y.) This scene is based on Samuel Richardson’s popular novel, Pamela (1740). According to Charles Saumarez Smith, “Pamela is shown in a space which she is clearly able to treat as her own with writing implements on the table in front of her; but her private space is invaded by Mr. B.” The tilt-top table is clearly the central fixture in Pamela’s specifically feminine space.

Gawen Hamilton, Family Group, England, ca. 1730. Oil on canvas. 28 1/2" x 35 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Tea table, probably Williamsburg, Virginia, 1710–1720. Walnut. H. 27 1/2", W. 26 1/2", D. 21 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) This is one of the earliest tea tables from the colonial period. It has finely turned columnar legs and an edge molding nailed to the top rather than being set into a rabbet.

Joseph van Aken, An English Family at Tea, ca. 1720. Oil on canvas. 39" x 45 3/4". (Courtesy, Tate Gallery.) The rectangular tea table illustrated in this painting has an applied edge molding, shaped skirt, and angular cabriole legs.

Tea table, possibly from the shop of Peter Scott, Williamsburg, Virginia, 1725–1740. Mahogany. H. 26 3/4", W. 29 1/2", D. 17 3/8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Nicolaas Verkolje (1673–1746), Two Ladies and a Gentleman at Tea, 1715–1720. Dimensions not recorded. (© V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London, www.vam.ac.uk) Art historian Peter Thornton notes that small oval tables like the one depicted in this scene were very popular in Holland. “Such forms often had a painted top which was hinged on a tripod pillar, so that when not in use, it could be placed close to the wall where it provided colorful decoration” (Authentic Décor: The Domestic Interior, 1720–1920 [New York: Viking, 1984], p. 79, no. 95).

Tea table, Philadelphia area of Pennsylvania, ca. 1720. Walnut and cherry. H. 27 1/8"; Diam. of top: 31 5/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Candle stand, Philadelphia, 1710–1720. Walnut. H. 28 7/8", W. 17 3/4", D. 16 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tea table, Philadelphia, 1730–1740. Mahogany. H. 28"; Diam. of top: 29 1/4". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; gift of Lydia Thompson Morris.)

Tea table with carving attributed to the shop of Samuel Harding, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1735–1745. Mahogany. H. 27"; Diam. of top: 31". (Courtesy, Diplomatic Reception Rooms, U. S. Department of State.)

Tea table attributed to Peter Scott, Williamsburg, Virginia, 1740–1750. Mahogany. H. 28 3/4"; Diam. of top: 32 13/16". (Courtesy, Robert E. Lee Memorial Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

View of the Dominy shop showing a table top mounted on a lathe. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) The Dominy family shop was located in East Hampton, Long Island.

Tea table, probably Norfolk, Virginia, 1760–1775. Mahogany. H. 28 3/4"; Diam. of top: 29 3/4". (Collection of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) This tea table probably represents the work of a cabinetmaker, a turner, and a carver.

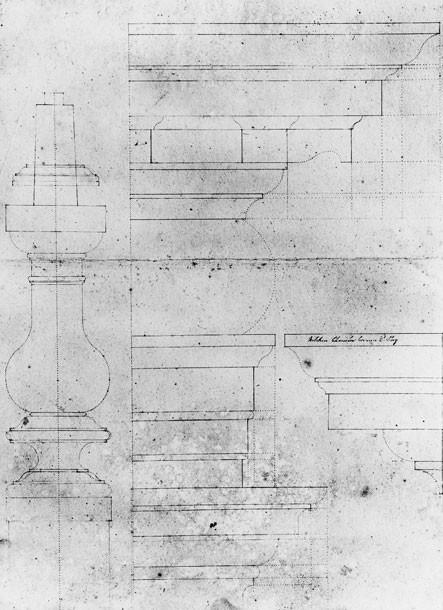

Thomas Hayden drawing of a baluster for a tilt-top tea table, Windsor, Connecticut, 1787. Dimensions not recorded. Ink on paper. The Great River: Art and Society of the Connecticut Valley, 1635–1820, edited by Gerald W. R. Ward and William N. Hosley, Jr. (Hartford, Conn.: Wadsworth Atheneum of Art, 1985), p. 225.

Tea table, Newport, Rhode Island, 1760–1770. Mahogany. H. 26 5/8"; Diam. of top: 31 7/8". (Photo, Israel Sack, Inc.)

Detail of three balusters in Touro Synagogue, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1763. (Courtesy, Touro Synagogue; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

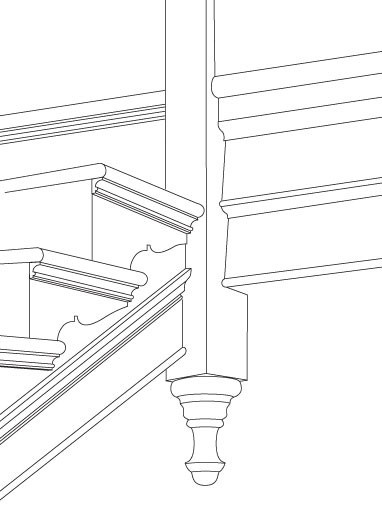

Detail of a pendant in the George Wythe House, Williamsburg, Virginia, 1750–1755. (Redrawn from an original by Singleton Peabody Moorehead; courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Tea table, New York, 1760–1770. Mahogany. H. 29"; Diam. of top: 29". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tea table, New York, 1760–1770. Mahogany. H. 29"; Diam. of top: 29". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the pillar of the tea table illustrated in fig. 20.

Detail of the pillar of the table illustrated in fig. 21.

Tea table with carving attributed to the shop of James Reynolds, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1766–1775. Mahogany. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; photo, Christie’s.)

Tea table with carving attributed to Bernard and Jugiez, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770–1775. Mahogany. H. 29 3/4"; Diam. of top: 31 1/2". (Courtesy, Dietrich American Foundation.)

Tea table, probably Boston, Massachusetts, 1750–1765. Mahogany. H. 27 1/2"; Diam. of top: 36". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

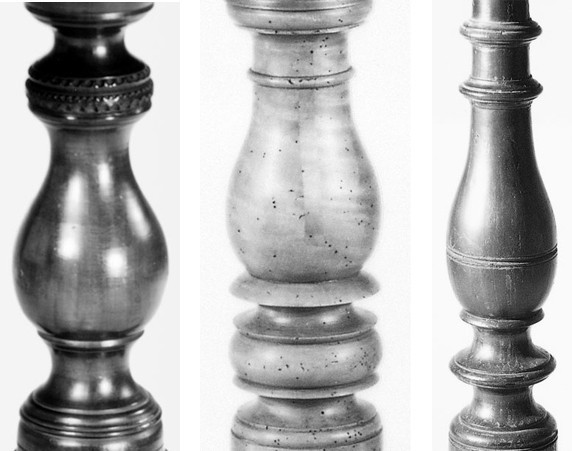

Detail showing the pillars on (from left to right): tea table, Boston or Salem, Massachusetts, 1760–1770; tea table, Newport, Rhode Island, 1760–1780; tea table, eastern Virginia, 1750–1770. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; John Nicholas Brown Center for the Study of American Civilization; private collection, photo, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Detail showing the pillars on (from left to right): tea table, Massachusetts, 1750–1770; tea table, Newport, Rhode Island, 1755–1775; tea table, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1740–1755; tea table, eastern Virginia, 1750–1770. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, gift of Mrs. H. K. Estabrook, photo, David Bohl; Philadelphia Museum of Art; Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Detail showing the pillars on (from left to right): tea table by Theodosius Parsons, Windham, Connecticut, 1787–1793; tea table, Pennsylvania, 1760–1780; tea table, Norfolk, Virginia, 1765–1775. (Courtesy, Mabel Brady Garvan Collection, Yale University Art Gallery; Winterthur Museum; Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Tea table, Norfolk, Virginia 1765–1785. Mahogany. H. 29 1/2"; Diam. of top: 37". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Tea table by Theodosius Parsons, Windham, Conecticut, 1787–1793. Cherry. H. 27 3/8"; Diam. of top: 36 1/4". (Courtesy, Mabel Brady Garvan Collection, Yale University Art Gallery.)

Detail showing the scalloped tops on (a) tea table, probably Connecticut, 1765–1785; (b) tea table, New York, 1765–1785; (c) tea table, Philadelphia, 1765–1775; (d) tea table, Charleston, South Carolina, 1760–1770. (Courtesy, Milwaukee Art Museum, Layton Art Collection; Chipstone Foundation; Winterthur Museum; Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Detail showing the legs of (from left to right): tea table, Virginia, 1750–1770; tea table, Philadelphia, 1765–1775. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Tea table, Charleston, South Carolina, 1760–1770. Mahogany. H. 28 1/2"; Diam. of top: 31 1/4". (Collection of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Tea table attributed to a member of the Chapin family, Hartford or East Windsor, Connecticut, 1775–1790. Cherry. H. 29 1/4"; Diam. of top: 31 1/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Eliphalet Chapin (1741–1807) worked as a journeyman in Philadelphia in the 1760s. When he returned to his native Connecticut, he continued to use construction features, proportions, and decorative details common in Philadelphia. His work influenced his cabinetmaker family members, Amzi (1768–1835) and Aaron (1753–1838).

Tea table, probably Newport, Rhode Island, 1750–1780. Mahogany. H. 28 1/4"; Diam. of top: 33". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Tea table, Newport, Rhode Island, 1760–1780. Mahogany. H. 27 1/2"; Diam. of top: 33 5/8". (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) Most Newport tea tables that appear to have been exported are relatively plain. It is doubtful that venture cargo shipments included elaborate examples like those occasionally made for Rhode Island patrons.

Desk, Newport, Rhode Island, 1760–1770. Maple with chestnut and tulip poplar. H. 40 7/8", W. 38 3/8", D. 20 7/16". (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Tea table, Chester County, Pennsylvania, 1788. Walnut, maple, ash, and lightwood inlay. H. 27"; Diam. of top: 23 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Epergne by William Cripps, London, 1759/60. Silver. H. 15 3/4", L. 26 1/4", W. 26". (Courtesy, Colonial Wiliamsburg Foundation.)

Robert West, Thomas Smith and His Family, Britain, 1733. Oil on canvas. 35 1/8" x 23 3/8". (Courtesy, National Trust Photographic Library/ Upton House, Beardstead Collection; photo, Angelo Hornak.)

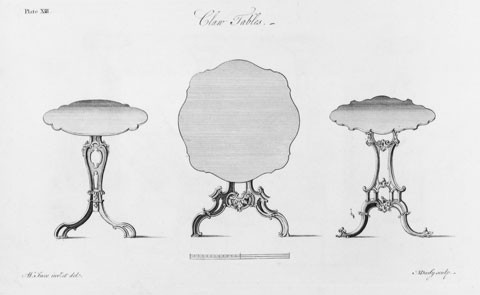

Designs for “Claw Tables” illustrated on plate 13 of the 1762 edition of William Ince and John Mayhew’s The Universal System of Household Furniture. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection.)

Tea table, Philadelphia, 1765–1775. Mahogany. H. 28 1/2"; Diam. of top: 36 1/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carving on the pillar of the tea table illustrated in fig. 43.

Tea table attributed to the shop of Peter Scott, Williamsburg, Virginia, 1765–1775. Mahogany. H. 28"; Diam. of top: 31 1/4 ". (Collection of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Kettle stand attributed to the shop of Peter Scott, Williamsburg, Virginia, 1765–1775. Mahogany. H. 31 1/4"; Diam. of top: 21". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the top of the kettle stand illustrated in fig. 46.

Tea table with carving attributed to Bernard and Jugiez, ca. 1765. Mahogany. H. 28 3/8"; Diam. of top: 36". (Kaufman Americana Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a leg on the tea table illustrated in fig. 48.

Tea table, probably Charleston, South Carolina, 1765–1775. Mahogany. H. 28 3/8"; Diam. of top: 29 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Detail of a leg on the tea table illustrated in fig. 50.

Similar creamware plates with different decorative treatment. (Left) probably Staffordshire, ca. 1775–1785; (right) possibly Leeds, ca. 1780–1790. (Courtesy, Audrey and Ivor Noël Hume; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)