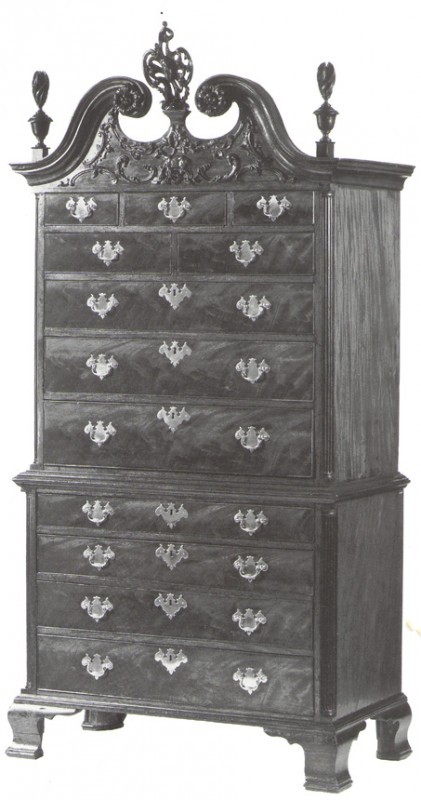

Pretreatment view of the lamb-and-ewe chest-on-chest showing the locations where finish samples were taken, Philadelphia, 1765-1775. Mahogany with white oak, white cedar, and yellow pine. H. 86", W. 42 7/8", D. 22 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, ace. 60.1056.)

Pediment of the chest-on-chest showing the locations where finish samples were taken. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Francis Barlow, engraving for Theophilia, London, 1652. (Courtesy, Chapin Library, Williams College.)

Detail of a carved tablet on a chimneypiece, Sanbeck Park, Yorkshire, England, 1750-1760. (Photo, Bradley Brooks.)

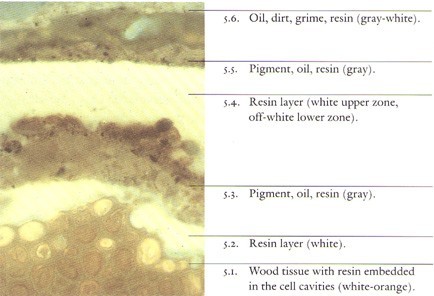

Sample from the scrollboard, average surface thickness 1.8 microns. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.) This sample was taken from a protected area of the scrollboard adjacent to the appliquÈ. Because the six layers represent an extensive finish history that might be complete, this sample was used as a standard for comparisons with other finish samples.

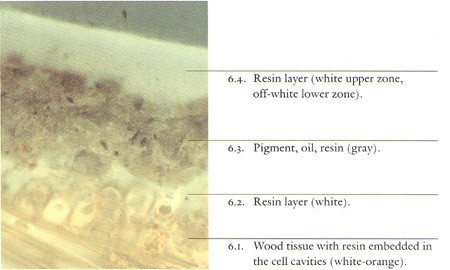

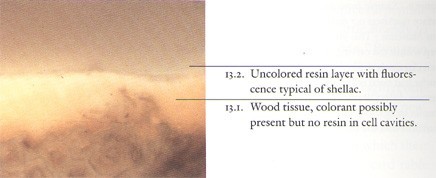

Sample from the rear leg of the ewe, average surface thickness 0.9 microns. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.) The layers in this sample compare favorably with four bottom lavers of the standard (5.1-5.4). There is also a faint film on top of layer 6.4 that could be an oil polish corresponding to laver 5.6. The correlation between the layers on these samples supports the visual observation that the ewe is original.

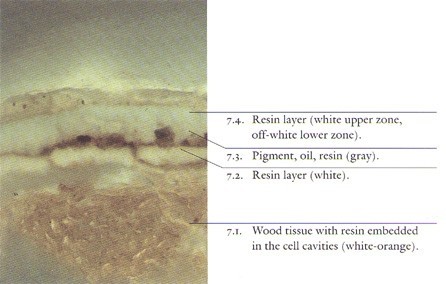

Sample from the right rosette, average surface thickness 0.75 microns. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.) The layers in this sample are consistent with the four bottom layers of the samples in figs. 5, 6. They also match cross sections taken from the left rosette, indicating that both rosettes are original to the chest-on-chest.

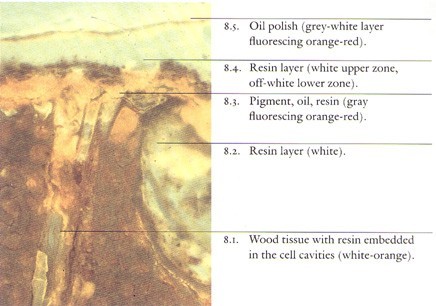

Sample from the left side of the upper case, average surface thickness 0.45 microns. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.) This sample was taken from a protected area on the back edge of the side. A reactive dye was added to this section to cause the oil layers to fluoresce orangered. The surface stratification of samples in figs. 5-7 is repeated with the exception of the uppermost layer (8.5) that corresponds with 5.6 in the standard sample. It is clear from the deep, orange-red fluorescence of layers 8.2 and 8.3 that the original finish included oil mixed with a resin.

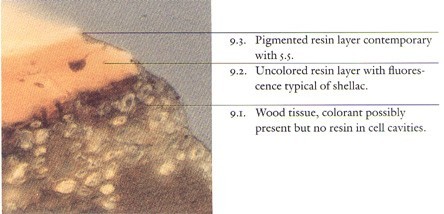

Sample from the cartouche, average surface thickness 0.7 microns. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.) This sample was taken from deep within the carving where it would have been extremely difficult to reach if the cartouche had been refinished. The surface stratification differs dramatically from that of the samples in figs. 5-8, lending support to the statement that the cartouche was added later.

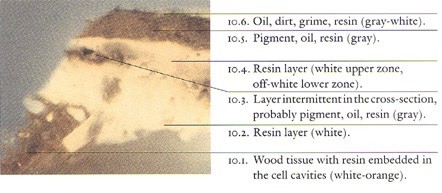

Sample from the flame section of the finial, average surface thickness 1 micron. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.) Although a note in the accession file states that the flames are new, they have a substantial finish history. The stratigraphy is very similar to that of the standard and suggests that the finials are old and probably original (compare with fig. 5). Philadelphia flame finials typically were made in three or four sections. Because individual sections could be lost or broken, a substantial number of period examples survive in a similarly restored condition.

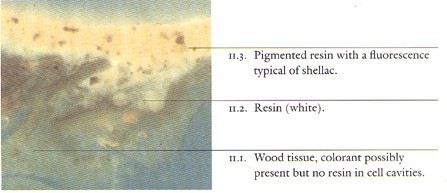

Sample from the turned section of the finial, average surface thickness 0.3 microns. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.) The surface history of this component contrasts with the flame but is similar to that of the replaced cartouche (figs. 9, 10). It may have been added at the same time as the cartouche.

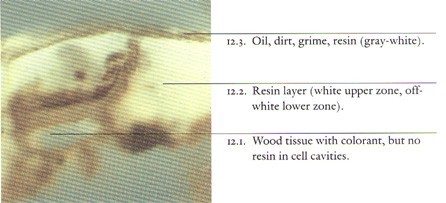

Finial plinth, average surface thickness 0.6 microns. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.) Although this section has a stratification that relates to part of the standard (5.4, 5.6), it is not possible to prove that the plinths are original. They probably are either original and have been refinished, or they are old replacements.

Sample from a scroll volute of the appliqué, average surface thickness 0.2 microns. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.) Samples were taken from areas of the carving which were thought to have been restored. This sample, taken from a scroll volute, has a stratigraphy that corresponds to the first two layers on the replaced cartouche (9.1, 9.2).

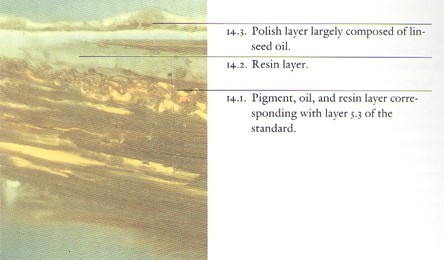

Sample from a drawer front, average surface thickness 0.5 microns. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.) This sample was taken from a section of the drawer less than 5 millimeters from the sample in fig. 15. It shows the finish prior to the enzyme treatment with the oil polish layer intact.

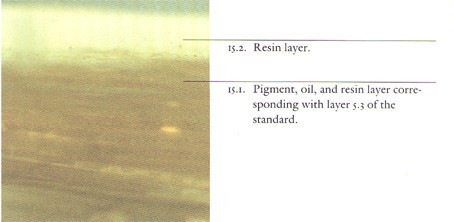

Sample from a drawer front, average surface thickness 0.5 microns. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.) This sample was taken from a section of the drawer less than 5 millimeters from the sample in fig. 14. after the application of the enzyme gel. The oil polish layer evident in fig. 14 has been removed and the underlying coatings left intact.

After-treatment view of the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)