Teapot, Staffordshire, 1765–1775. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 4 1/2". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation; unless otherwise noted, photos by Gavin Ashworth.)

Map showing locations related to the activities of John Bartlam and William Ellis. (Artwork by Wynne Patterson.)

Waster fragments, John Bartlam, Cain Hoy, South Carolina, 1765–1770. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology.)

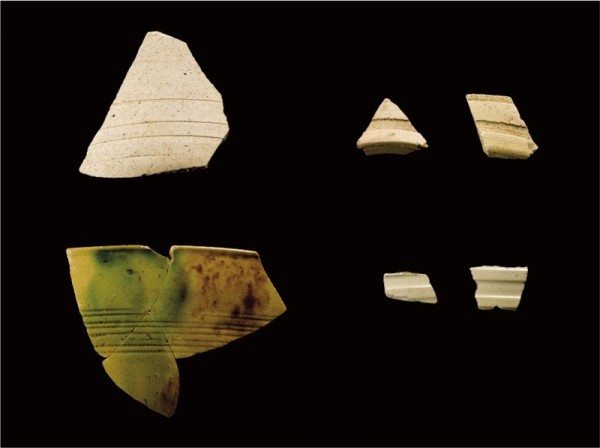

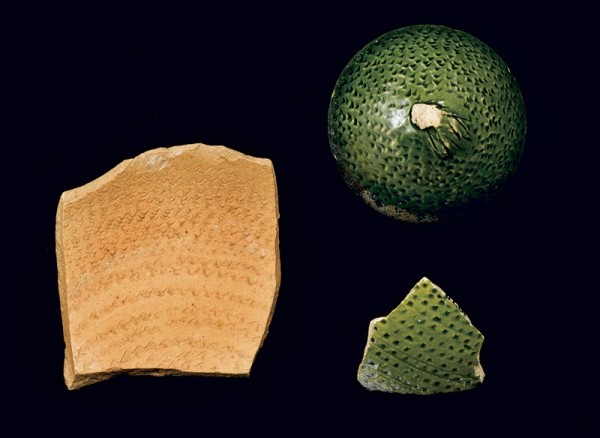

Waster fragments, John Bartlam, Cain Hoy, South Carolina, 1765–1770. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology.)

Bowl and mug fragments, John Bartlam, Cain Hoy, South Carolina, 1765–1770. Bisque-fired and lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology.) These fragments show clear evidence of lathe-turning. The four mug fragments at far right are virtually identical to a popular decorative technique used on Staffordshire hollow wares in the 1770s.

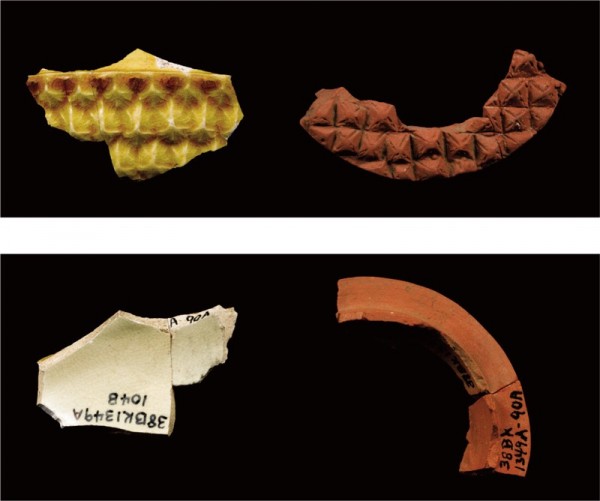

Teapot fragments, John Bartlam, Cain Hoy, South Carolina, 1765–1770. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology.) Note the incorporation of the molded Barleycorn design on the panels of the vessel.

Teapot fragments, attributed to John Bartlam, Cain Hoy, South Carolina, 1765–1770. Lead-glazed earthenware and unglazed red stoneware. (Courtesy,p> South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology.) This form in red stoneware has not been seen in English examples.

Bowl fragments, John Bartlam, Cain Hoy, South Carolina, 1765–1770. Bisque-fired and lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology.)

Dish fragments, attributed to John Bartlam, Cain Hoy, South Carolina, 1765–1770. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology.)

Dish, Staffordshire, 1765–1775. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 8 3/8". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation.)

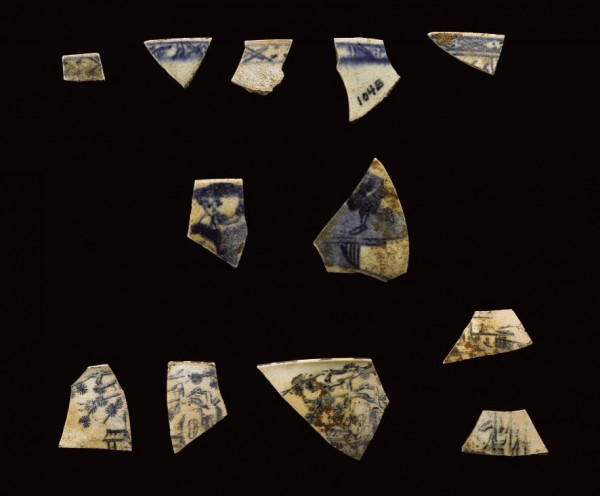

Teabowl fragments, John Bartlam, Cain Hoy, South Carolina, 1765–1770. Soft-paste porcelain. (Courtesy, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology.)

Waster fragment, John Bartlam, Cain Hoy, South Carolina, 1765–1770. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology.) This fragment clearly shows a collapsed vessel, the result of overfiring in the kiln.

Bowl fragments, John Bartlam, Cain Hoy, South Carolina, 1765–1770. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology.) The tortoise-glazed fragment on the left shows a rouletted rim pattern.

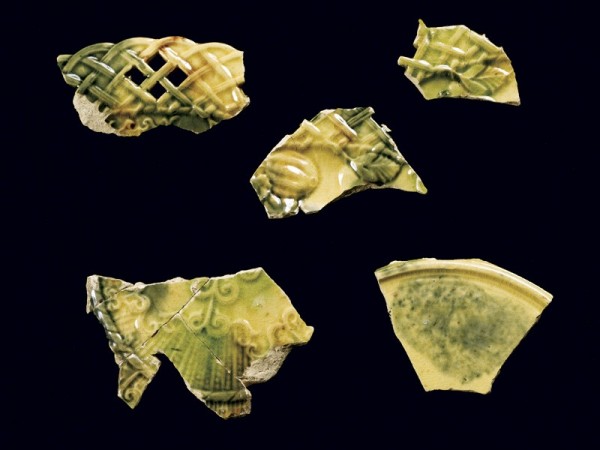

Plate and hollow ware fragments in the Barleycorn design, John Bartlam, Cain Hoy, South Carolina, 1765–1770. Bisque-fired and lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology.)

Plate fragments in the Dot, Diaper, and Basket design, John Bartlam, Cain Hoy, South Carolina, 1765–1770. Bisque-fired and lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology.)

Plate fragments in the Ring and Dot design, John Bartlam, Cain Hoy, South Carolina, 1765–1770. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology.)

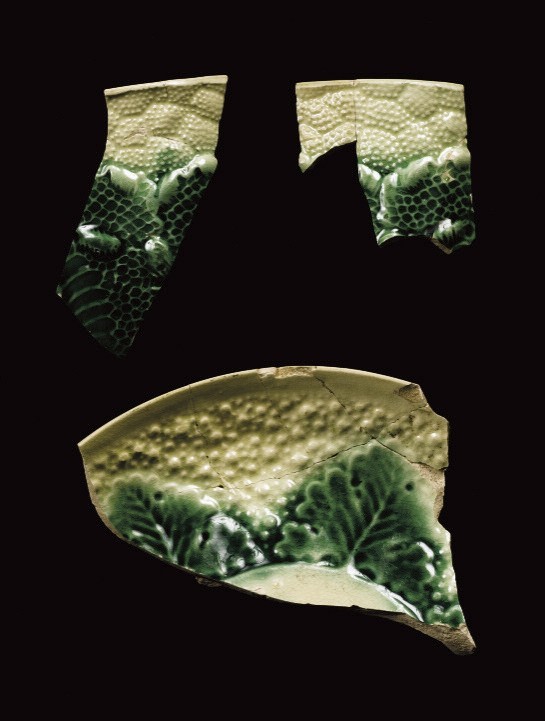

Bowl and saucer fragments in the molded Cauliflower pattern, attributed to John Bartlam, Cain Hoy, South Carolina, 1765–1770. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology.)

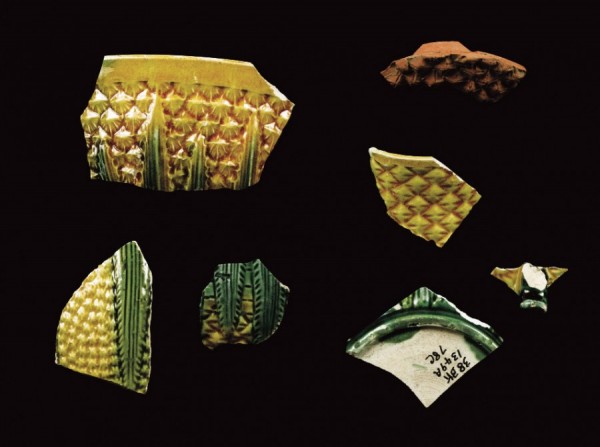

Fragments in the molded Pineapple pattern, attributed to John Bartlam, Cain Hoy, South Carolina, 1765–1770. Lead-glazed earthenware and unglazed red stoneware. (Courtesy, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology.)

Hollow ware fragments, John Bartlam, Cain Hoy, South Carolina, 1765–1770. Bisque-fired and lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology.)

Jug fragment, John Bartlam, Cain Hoy, South Carolina, 1765–1770. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology.)

Tortoise-glaze fragments, John Bartlam, Cain Hoy, South Carolina, 1765–1770. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology.)

Hollow ware fragment, John Bartlam, Cain Hoy, South Carolina, 1765–1770. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology.)

Figural fragments, attributed to John Bartlam, Cain Hoy, South Carolina, 1765–1770. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology.) These fragments might be from wares Bartlam produced using molds that were widely available in the Staffordshire ceramic industry.