View of Shepherd Mountain looking northwest from Interstate 64, just west of its intersection with the Uwharie River. The peak is 1,150 feet above sea level. (Photo, Alain C. Outlaw.)

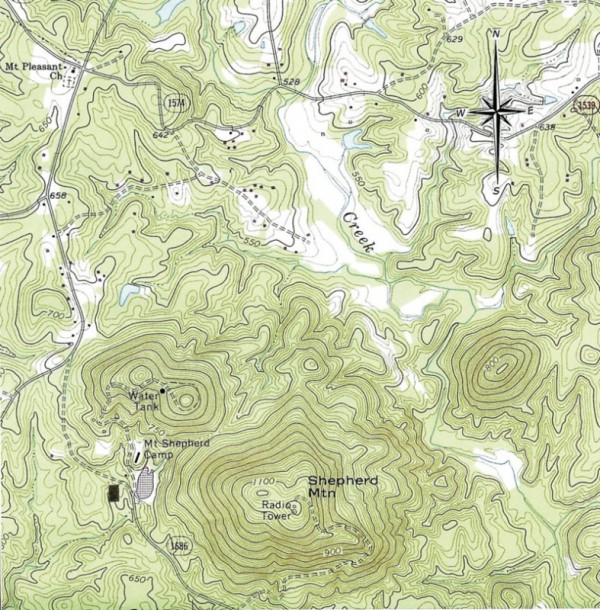

Detail of U.S. Geological Survey Quadrangle of Glenola, North Carolina, 1981, showing the topographic setting of the Mount Shepherd pottery site and the network of roads to the north, several likely dating to the colonial period. The site, marked by a black rectangle, measures 200' x 200'; the contour interval is 10'.

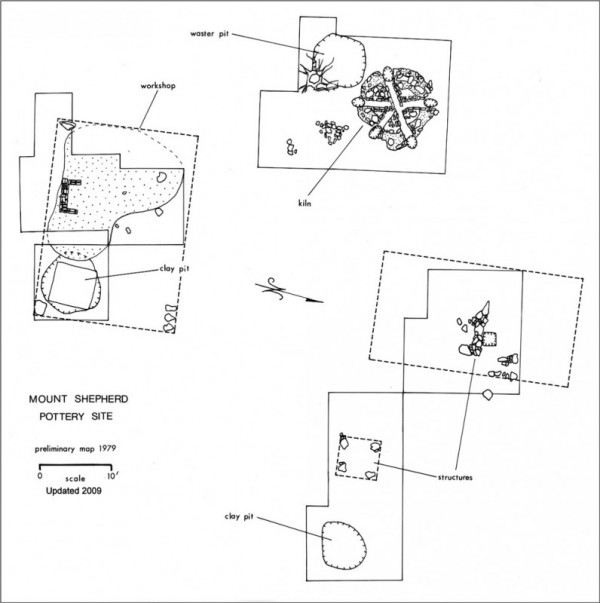

Drawing showing conjectured structure outlines. (All site drawings by Alain C. Outlaw.) This drawing is an updated version of the one submitted in 1979 with the National Register of Historic Places nomination form.

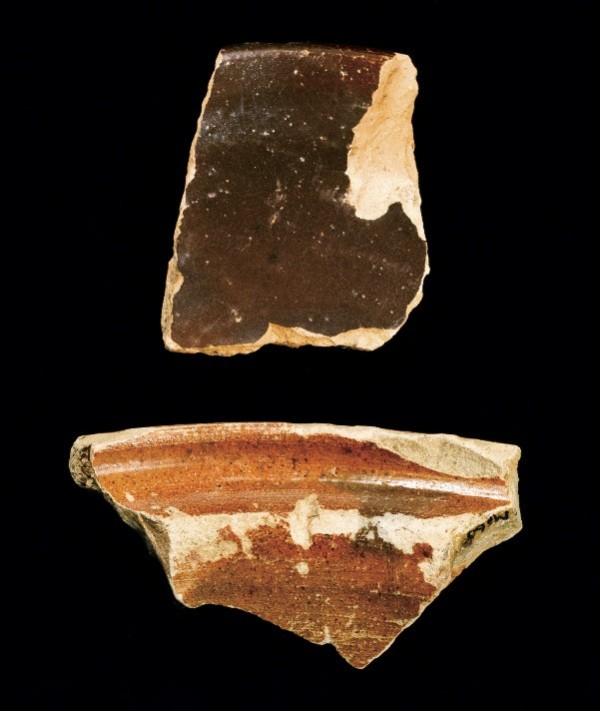

Native American pottery sherds, North Carolina piedmont, 500–1000. Low-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center; unless otherwise noted, photos by Gavin Ashworth.) Only seven prehistoric ceramics sherds were found during excavations, indicating that Native Americans did not occupy the site during the Woodland period.

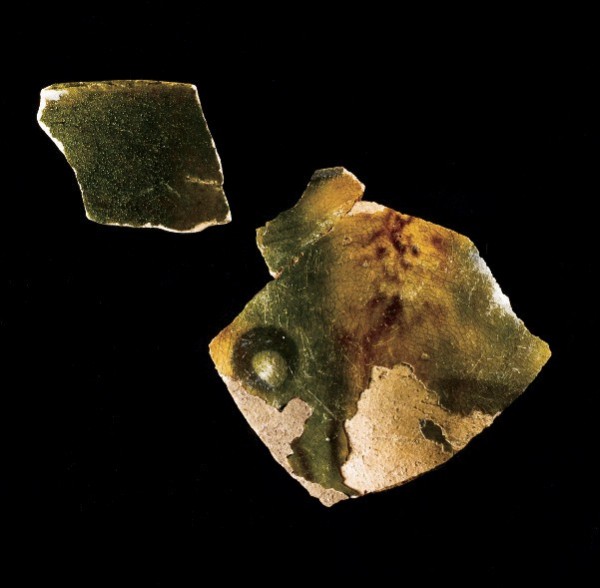

Jug fragments, Germany, 1750–1770. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.) The decorative checkerboard design on this vessel may have been a design source for the fragmentary dish illustrated in fig. 46.

Saucer (left) and teabowl (right) fragments, England, post-1770. Creamware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.) The presence of this ware type helped to date the site to post-1770.

View of the kiln at the Mount Shepherd site prior to excavation. (Photo, Alain C. Outlaw.) This feature was covered by a circular mound of rocks. J. H. Kelly and A. R. Mountford excavated the backfilled trench on the left in 1971.

Post-excavation view of the kiln. (Photo, Alain C. Outlaw.) A waster pit is visible in the upper left corner of the excavated area.

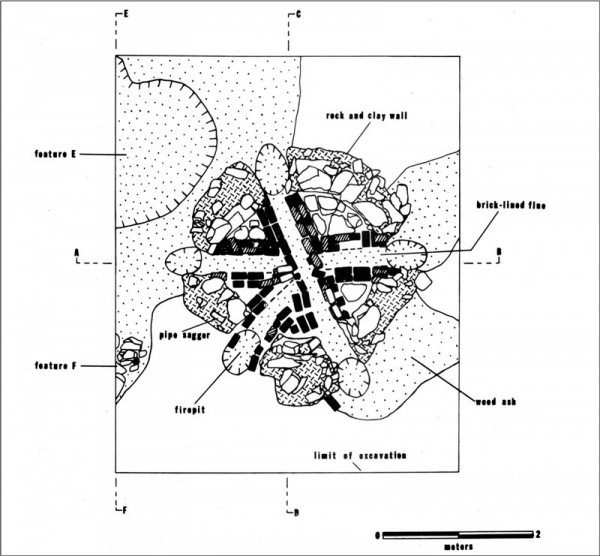

Drawing of the floor plan of the Mount Shepherd kiln.

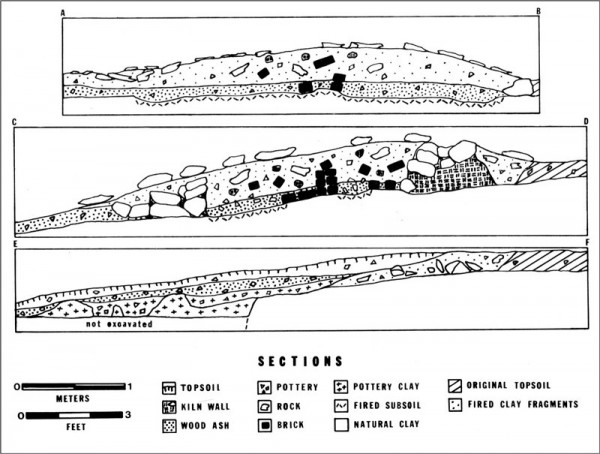

Sectional drawing of the Mount Shepherd kiln.

Drawing of a pottery kiln (left) and pipe kiln (right) by Reinhold Rücker Angerstein, probably England, 1753–1755. (R. R. Angerstein’s Illustrated Travel Diary, 1753–1755: Industry in England and Wales from a Swedish Perspective, trans. Torsten Berg and Peter Berg [London: Science Museum, 2001], pp. 204, 311.) According to Angerstein, the pottery kiln was near Prescott, England. The pipe kiln was near Liverpool and had “six little fireplaces.”

Trivets, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. High-fired clay. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Kiln props and spacers, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. High-fired clay. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Saggers, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. High-fired clay. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Jar fragments from the last firing lie in a brick-lined flue inside the kiln. (Photo, Alain C. Outlaw.) The center of the kiln is at top center.

Crocks, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. of crock at right 7 1/8". (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Crock rim fragment, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Crocks and chamber pot, recovered at Gottlob Krause’s pottery site, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1789–1802. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

View of the excavated workshop area at the Mount Shepherd site. (Photo, Alain C. Outlaw.)

Reassembled marlys from five dishes, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Bowl fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

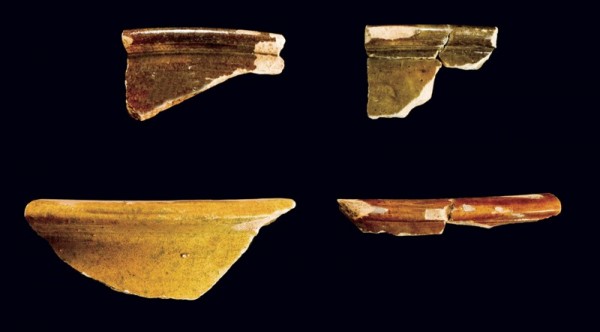

Bowl fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Bowl fragment, recovered at Gottfried Aust’s pottery site, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1756–1770. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park; photo, Wesley Stewart.)

Cream jar rims, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Jar base fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.) The illustrated marks are VI, VIII, and X.

Partially reassembled dish, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Dish rim fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.) Salem dishes with similar backs and rims are illustrated in “Eighteenth-Century Earthenware from North Carolina” by Luke Beckerdite and Johanna Brown in this volume.

Partially reassembled dish, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Dish fragment, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

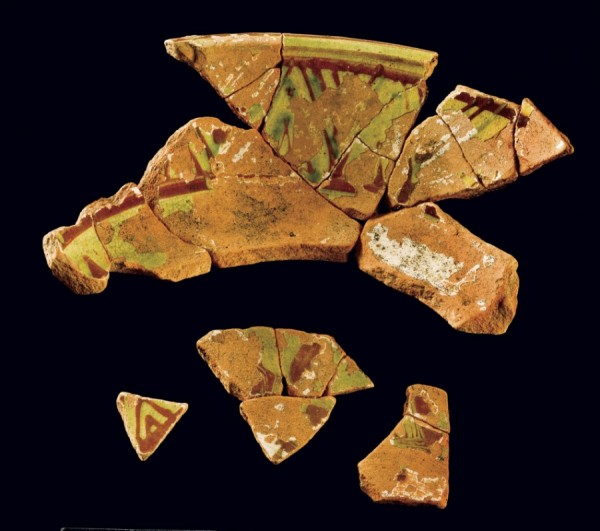

Dish fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Partially reassembled marly from a dish, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Partially reassembled marlys from two dishes, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Dish fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.) The decoration on the cavetto fragments is closely related to that on sherds recovered at Gottlob Krause’s pottery site in Bethabara (see in this volume Beckerdite and Brown, “Eighteenth-Century Earthenware from North Carolina,” fig. 69).

Dish fragment, recovered at Lot 49, Salem, North Carolina, 1775–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) This glazed marly fragment shows how Meyer’s scrolling-vine-and-leaf motif would have looked after firing (see fig. 32).

Detail of the marly of a fragmentary plate, recovered at Lot 49, Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1810. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Dish fragment, recovered at Gottlob Krause’s pottery site, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1789–1802. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Dish fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

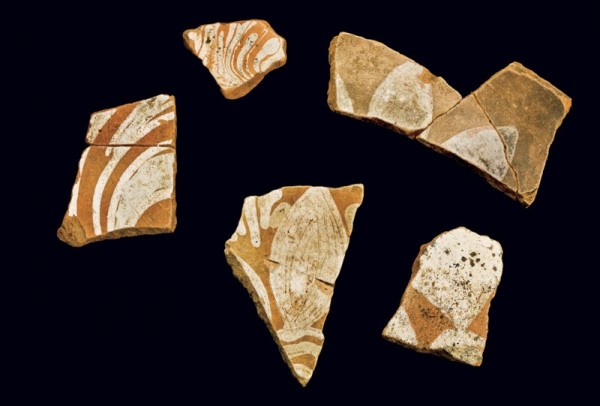

Dish fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.) The leaves are strikingly similar to those on fragments recovered at Salem and on several of the intact examples of Wachovia slipware illustrated in this volume in Beckerdite and Brown, “Eighteenth-Century Earthenware from North Carolina,” figs. 32, 35.

Dish, Salem, North Carolina, 1780–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 11 5/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

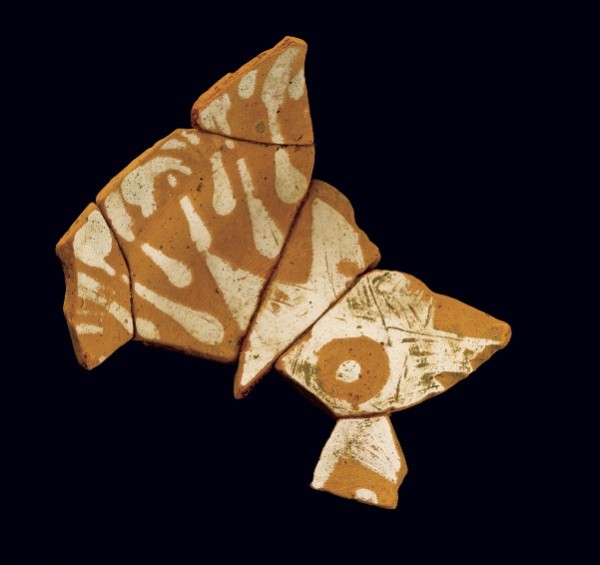

Dish fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.) Marks left by the decorator’s trailer are visible on the broad leaf on the triangular sherd in the center.

Detail of a dish probably made during Rudolph Christ’s tenure as master of the pottery at Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1810. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, The Barnes Foundation.) Marks left by the tip of the decorator’s trailer are visible on the tulip-shaped flower.

Dish fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Dish fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Dish fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Dish fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware and lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Dish fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Porringer fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Porringer fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Porringer fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Interior view of the porringer illustrated in fig. 49.

Porringer, probably Salem, North Carolina, 1780–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Private collection.)

Porringer, probably Salem, North Carolina, 1780–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Private collection.)

Porringer fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Porringer, recovered at Gottfried Aust’s pottery site, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1756–1771. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Jug or bottle mouths, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

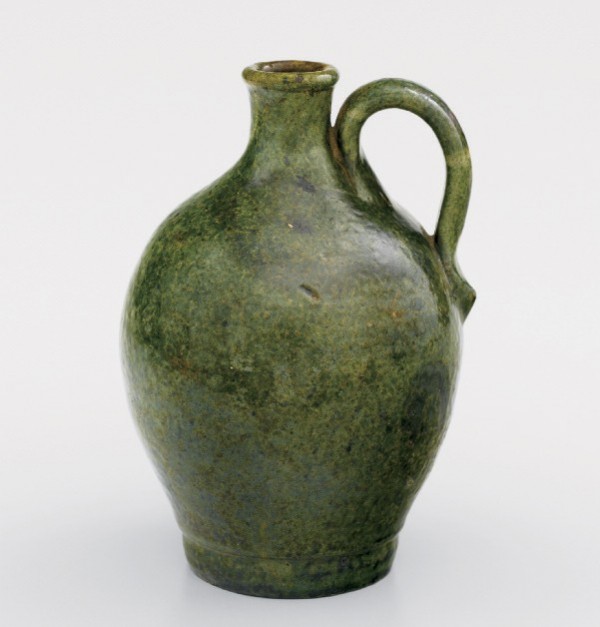

Jug, probably Salem, North Carolina, 1780–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Private collection.)

Jug, probably Salem, North Carolina, 1780–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Private collection.)

Jug fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Base fragments from mugs, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Base fragments from mugs, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Mug rim fragment, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Mug, probably Salem, North Carolina, 1780–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Fragmentary teabowl, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center; photo, John Bivins.) The current location of this fragment is not known.

Teabowl fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.) These sherds and those illustrated in fig. 63 could be from the same teabowl.

Teabowls, recovered at Gottlob Krause’s pottery site, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1789–1802. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.) The white-slip coatings of these bowls suggest that they were intended to have green or tortoiseshell glazes.

Milk pan fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Handle fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Lid fragment and rim fragment, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Jar fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Tile stove, Salem, North Carolina, 1775–1830. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens; photo, Wesley Stewart.)

Photograph of a pottery workroom, Salem, North Carolina, 1905. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The stove was used at the Schaffner-Krause pottery in Salem.

Stove tile, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

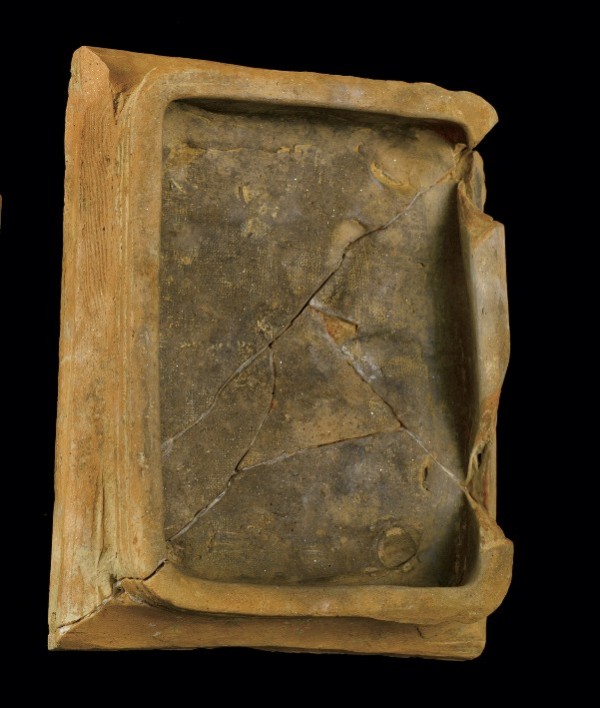

Stove tile, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

View of the back of the stove tile illustrated in fig. 72.

Detail of the back of the stove tile illustrated in fig. 72.

Fragmentary stove tile, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Pipe bowl, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Pipe bowl (front view), Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Side view of the pipe bowl illustrated in fig. 78.

Bottom view of the pipe bowl illustrated in figs. 78 and 79, showing the tripartite motif.

Sagger fragment with pins and pipes, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Dish fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Sugar bowl, possibly Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Private collection.)