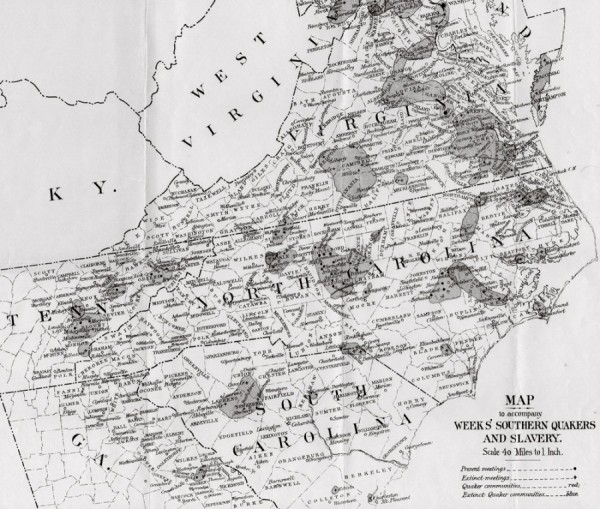

Map showing southern Quaker communities. Reproduced from Stephen B. Weeks, Southern Quakers and Slavery: A Study in Institutional History (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins Press, 1896). (Courtesy, Friends Historical Collection, Guilford College.)

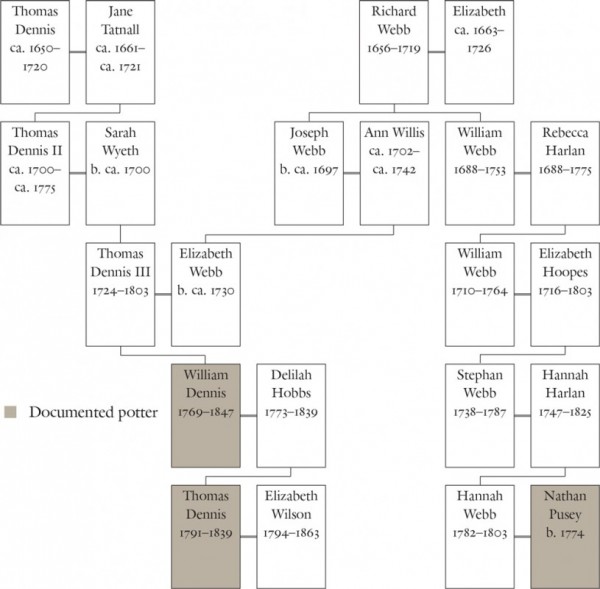

Dennis and Webb family tree. (Compiled by Hal Pugh and Eleanor Minnock-Pugh; artwork, Wynne Patterson.)

n Documented potter

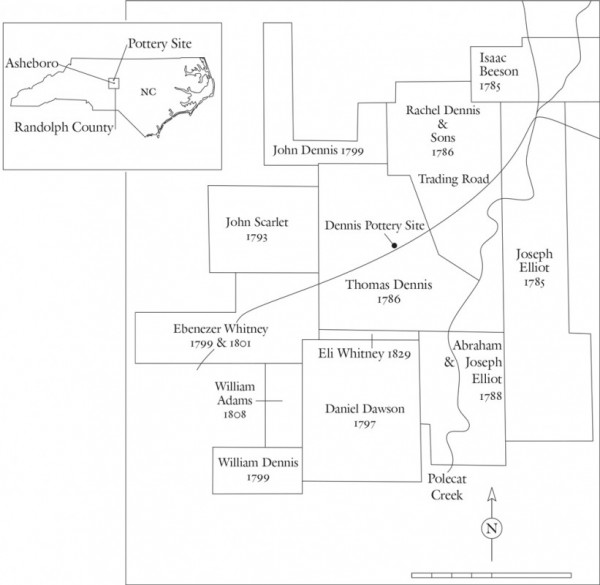

Plat map showing the location of the Dennis Pottery and surrounding landowners. Dates represent the year individuals either applied for or were granted land from the state of North Carolina.

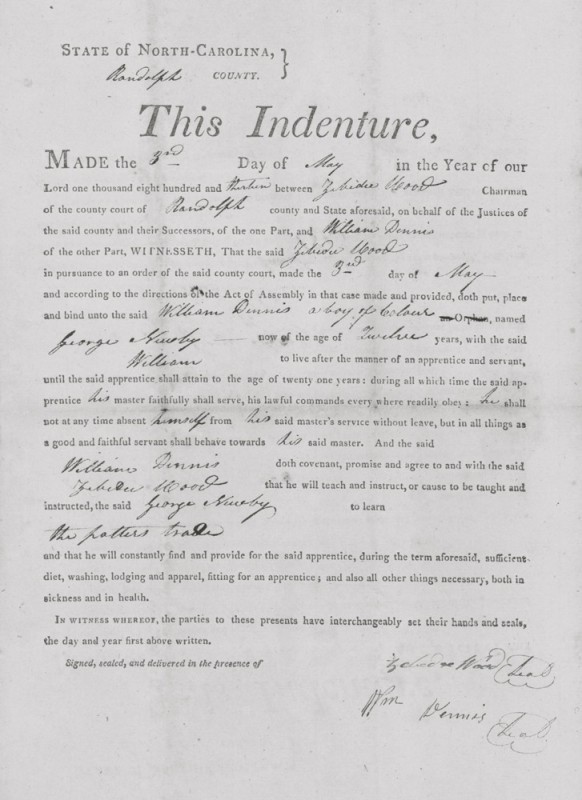

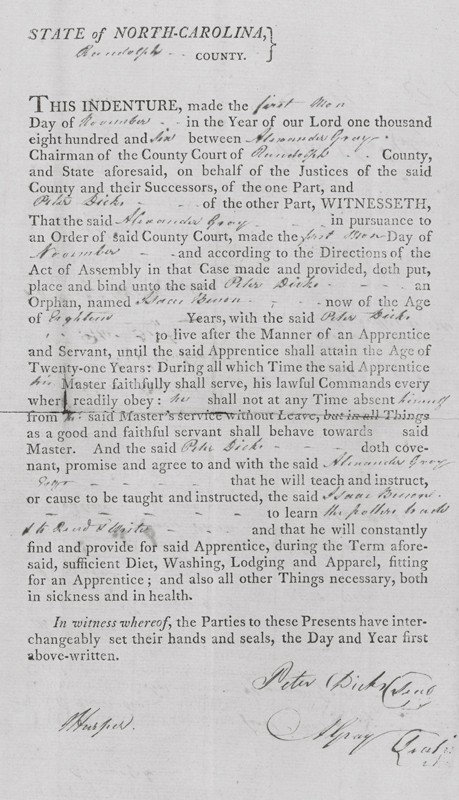

Indenture of George Newby, Randolph County, North Carolina, May 3, 1813. (Courtesy of the North Carolina Office of Archives and History, Raleigh, North Carolina.)

William Dennis House, New Salem, North Carolina, ca. 1820. (Photo, Hal Pugh.)

Dish fragment recovered at the Thomas Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1812–1821. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Private collection; unless otherwise noted, all photos by Gavin Ashworth.)

Kiln tiles recovered at the Thomas Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1812–1821. High-fired clay. (Private collection.) The tiles on the right are fused together with glaze.

Saggar recovered at the Thomas Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1812–1821. H. 7". High-fired clay. (Private collection.) The saggar is representative of the type and size used at both Dennis potteries. On this example, part of the rim has been pinched between the thumb and forefinger to form a decoration, but the vessel was never finished.

Kiln furniture recovered at the William Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. High-fired clay. (Private collection.) The ungrooved tile shown at top is vitrified from continual refiring and has adhering saggar and creampot rims from a kiln mishap.

Dish fragments recovered at the William Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Private collection.)

Saggar fragments recovered at the William Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. High-fired clay. (Private collection.)

Dish, attributed to the William Dennis pottery, New Salem, North Carolina, 1812. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 13 1/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Dish, attributed to the Dennis potteries, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 13 1/2". (Courtesy, North Carolina Pottery Center.)

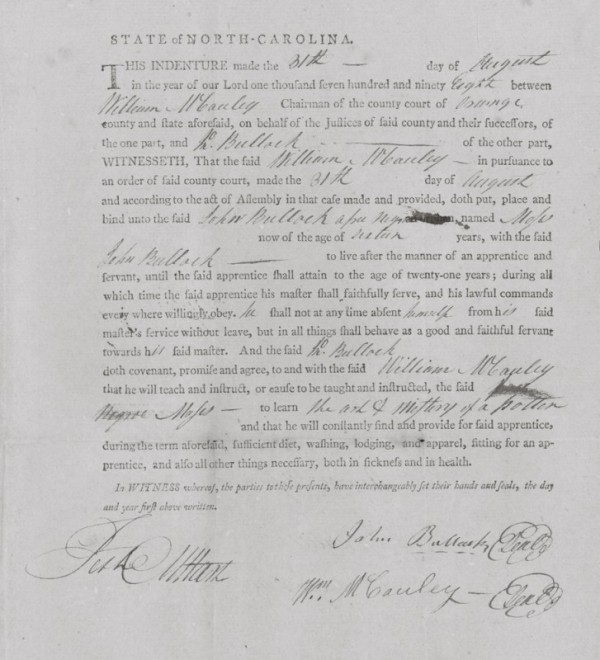

Indenture of Moses Newby, Orange County, North Carolina, August 31, 1798. (Courtesy of the North Carolina Office of Archives and History, Raleigh, North Carolina.)

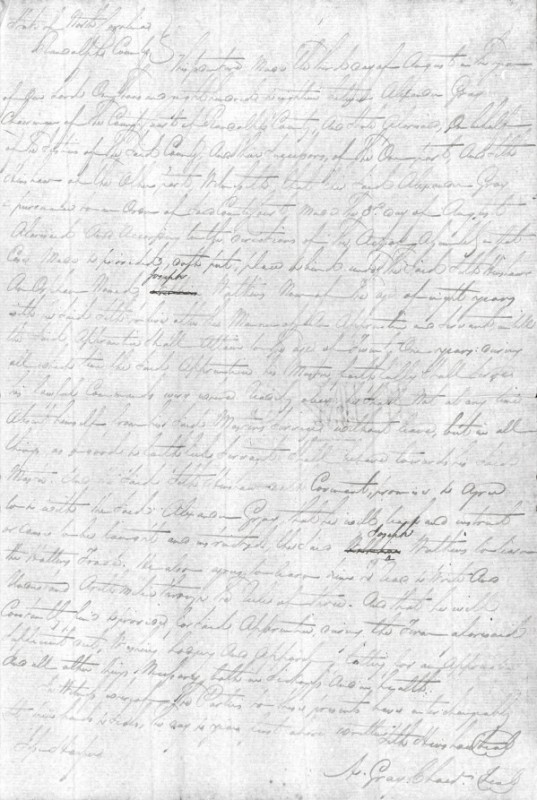

Indenture of Joseph Watkins, Randolph County, North Carolina, August 3, 1818. (Courtesy of the North Carolina Office of Archives and History, Raleigh, North Carolina.)

Jar, Henry Watkins, Randolph or Guilford County, North Carolina, 1821–1850. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 7 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

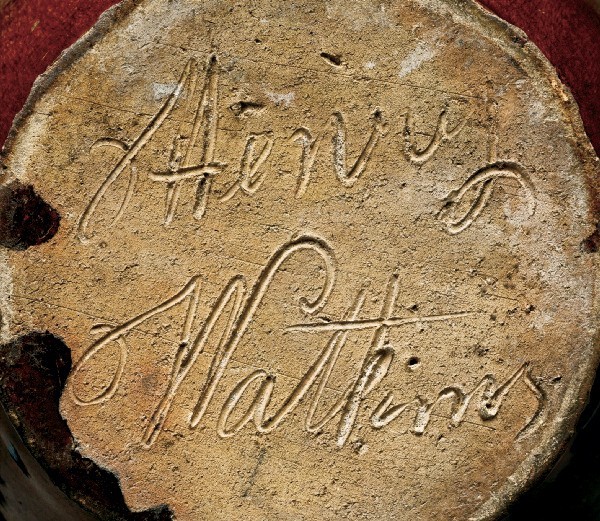

Detail of the incised signature on the bottom of the jar illustrated in fig. 16.

Dish, attributed to Henry Watkins, Randolph or Guilford County, North Carolina, 1821–1850. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 12". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Fat lamps, attributed to Henry Watkins, Randolph or Guilford County, North Carolina, 1821–1850. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 6 1/8" (right). (Private collection [left]; courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens [right].) The example on the right shifted in the kiln and fired upside down.

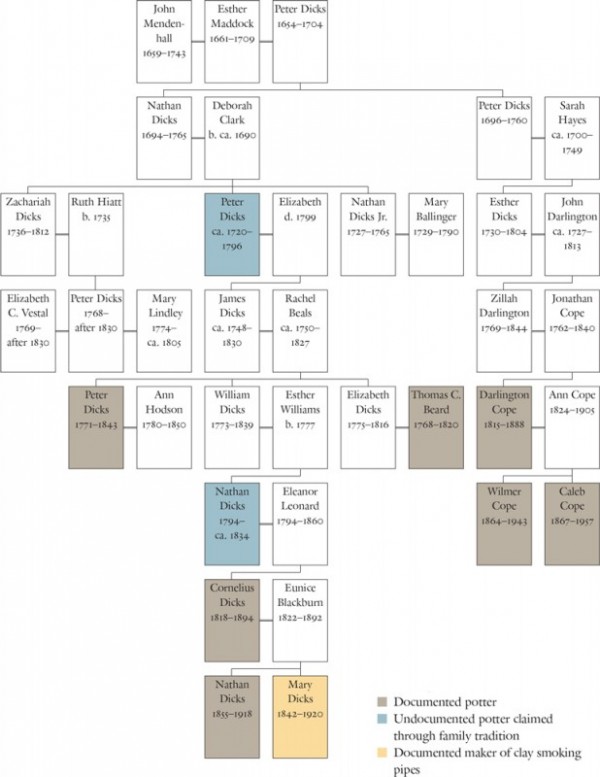

Dicks Family of Potters. (Compiled by Hal Pugh and Eleanor Minnock-Pugh; artwork, Wynne Patterson.)

n Documented potter

n Undocumented potter claimed through family tradition

n Documented maker of clay smoking pipes

Indenture of Isaac Beeson, Randolph County, North Carolina, November 3, 1806. (Courtesy of the North Carolina Office of Archives and History, Raleigh, North Carolina.)

Pipe press and molds, Cornelius Dicks, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1850–1920. Hardwood (press) and pewter (molds). H. 13 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Hal Pugh.)

Photograph of Mary Elizabeth Dicks Davis (1842–1920). (Courtesy, Ann S. Turner.)

Clay smoking pipes, Mary Elizabeth Dicks Davis, Randolph County, North Carolina, ca. 1900. (Private collection.)

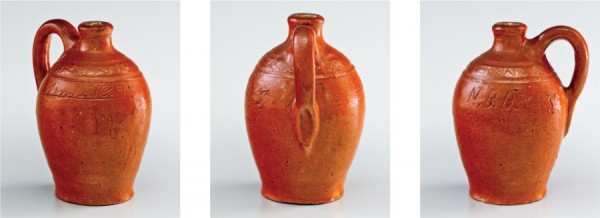

Jug, Nathan Dicks, Randolph County, North Carolina 1890. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5 1/2". Inscribed on shoulder: “N. B. DICKS. new market n.c. Jan 12 1890 1 Pt.” (Private collection.) Handles on earthenware associated with Dicks family potters often have an elongated lower terminal.

Skillet, attributed to Nathan Dicks, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1875–1910. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 10 5/8" with 5 1/4" handle. (Private collection.)

Pitcher, attributed to Nathan Dicks, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1875–1910. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 6 1/4". (Private collection.)

Jars, attributed to Nathan Dicks, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1875–1910. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 9 1/2" (right). (Private collection.) These jars exhibit the elongated handle terminal and incised wavy line decoration characteristic of Nathan Dicks.

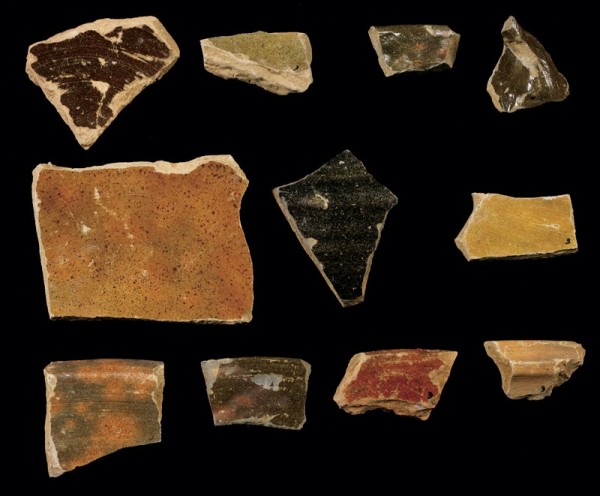

Fragments recovered at the Nathan Dicks pottery site, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1875–1910. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Private collection.)

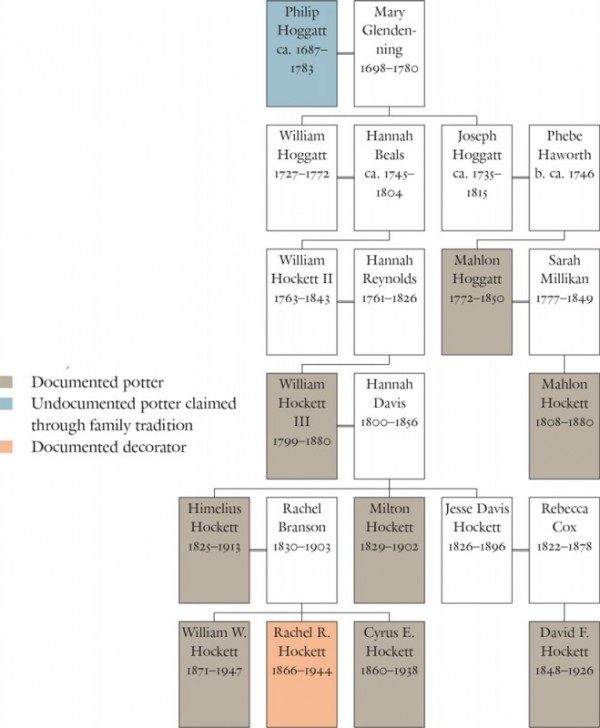

Hoggatt/Hockett Family of Potters. (Compiled by Hal Pugh and Eleanor Minnock-Pugh; artwork, Wynne Patterson.)

n Documented potter

n Undocumented potter claimed through family tradition

n Documented decorator

Dish, possibly made by a member of the Hoggatt/Hockett family of potters, northern Randolph/southern Guilford County, North Carolina, 1785–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 6 1/2". (Private collection.) The rear profile of this dish is similar to that of Moravian examples, but it was removed from the wheel with a twisted cord—a technique not associated with Moravian work.

Photograph of William Hockett III (1799–1880). (Courtesy, Jane Coltrane Norwood.)

Bottle, attributed to William Hockett III, northern Randolph/southern Guilford County, North Carolina, 1879. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 7 1/4". Inscribed on shoulder: “WM RR H 4-19-1879.” (Private collection).

Photograph of Rachel Rodema Hockett (1866–1944), granddaughter of William Hockett III and daughter of Himelius Mendenhall Hockett. (Courtesy, Jane Coltrane Norwood.)

Photograph of Himelius Mendenhall Hockett (1825–1913). (Courtesy, Jane Coltrane Norwood.)

Chest, attributed to William Hockett III, northern Randolph/southern Guilford County, North Carolina, 1828. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 3 3/8". (Private collection.) The chest is slab-built.

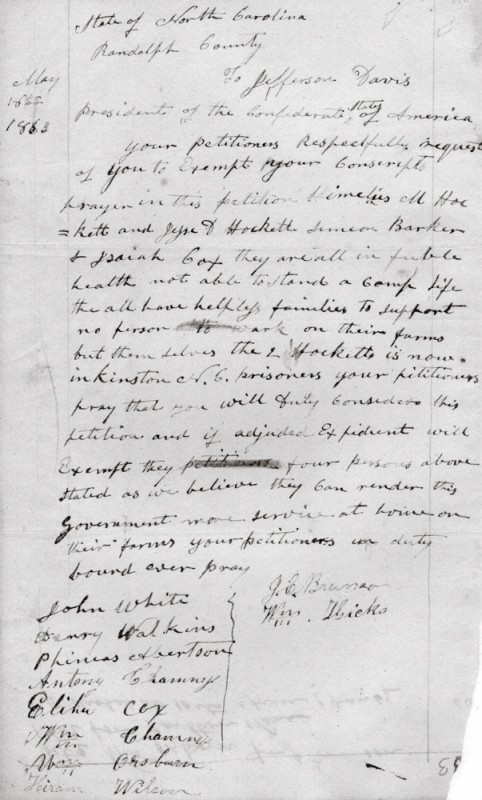

Petition from John Branson to Jefferson Davis, May 18, 1863, requesting the exemption of Himelius Hockett and others. The petition, written on an older account ledger page, was signed by ten neighbors, including potter Henry Watkins. (Courtesy, Friends Historical Collection, Guilford College.)

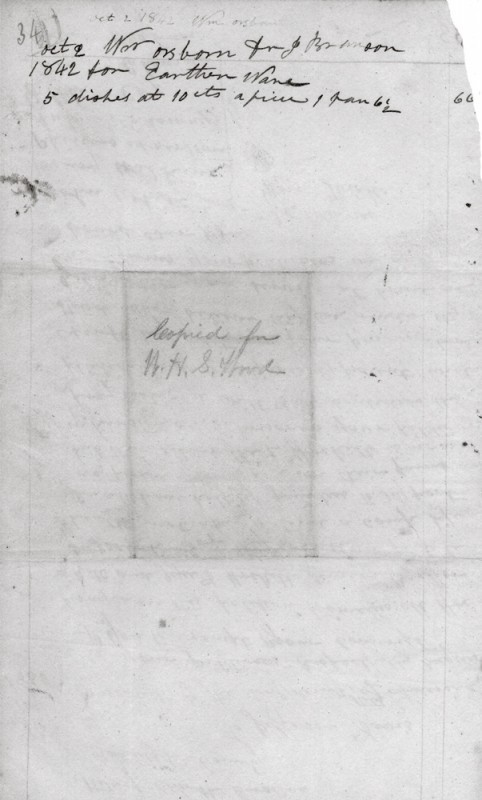

Reverse side of the petition illustrated in fig. 37. On this side, numbered page 34, is recorded an earthenware sale between John Branson and William Osborn: “Oct. 2 1842 Wm Osborn fr J Branson for Earthen Ware 5 dishes at 10 cts a piece 1 pan 6 1/2.”

Colander, attributed to the William Hockett/Hoggatt family of potters, northern Randolph/southern Guilford County, North Carolina, ca. 1860. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 4 3/8". (Private collection.)

Drain tile, David Franklin Hockett, Randolph County, North Carolina, ca. 1875. Unglazed earthenware. L. 6 1/2". (Private collection.)

Exterior view of the David Franklin Hockett kiln, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1875–1910. (Photo, Hal Pugh.)

Interior view of the David Franklin Hockett kiln showing rock lining, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1875–1910. (Photo, Hal Pugh.)

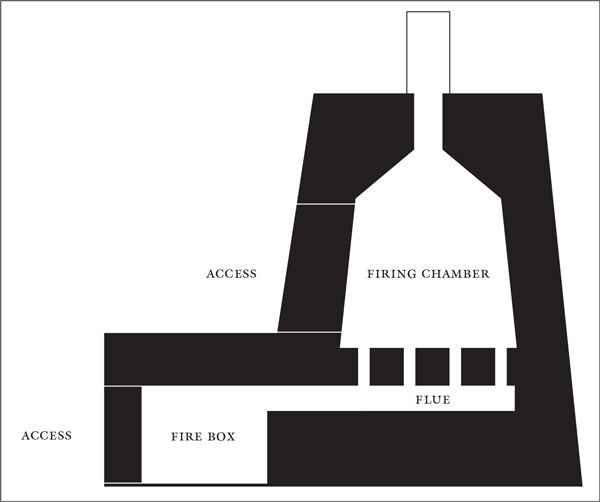

Drawing of the David Franklin Hockett kiln, based on eyewitness accounts.

Overhead view of the partially excavated William Dennis kiln footprint, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1790–1832. (Photo, Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton.) It is similar in size and shape to the firing chamber of the David Franklin Hockett kiln.

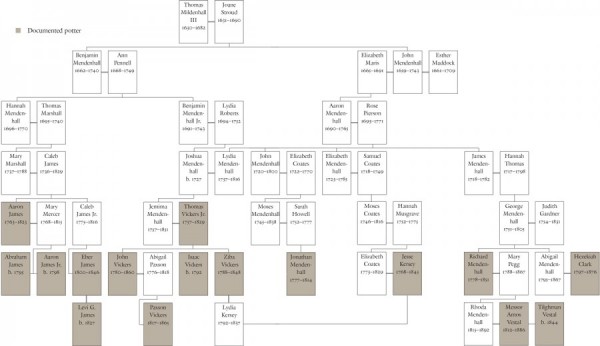

Mendenhall Family of Potters. (Compiled by Hal Pugh and Eleanor Minnock-Pugh; artwork, Wynne Patterson.)

n Documented potter

Richard Mendenhall house, Jamestown, Guilford County, North Carolina, ca. 1811. (Courtesy of the North Carolina Office of Archives and History, Raleigh, Norh Carolina.)

Richard Mendenhall store, Jamestown, Guilford County, North Carolina, 1824. (Courtesy of the North Carolina Office of Archives and History, Raleigh, North Carolina.) The store was situated across the road from the house illustrated in fig. 46.

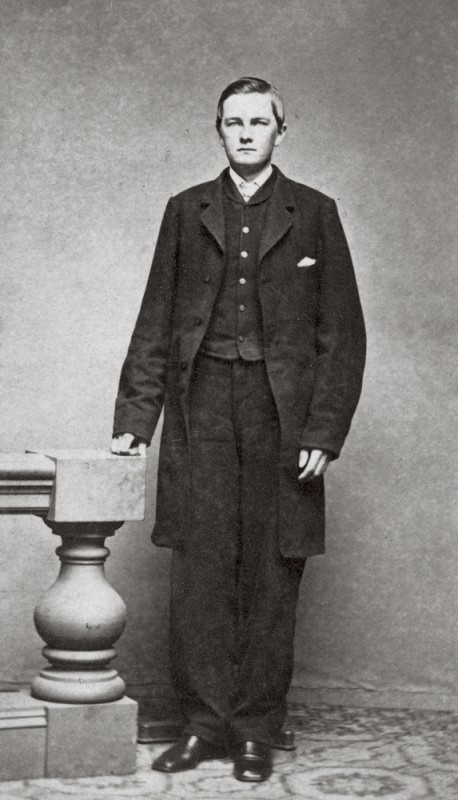

Tilghman Vestal, photo taken in 1866 by H. G. Pearce, Providence, Rhode Island. (Courtesy, Friends Historical Collection, Guilford College.)

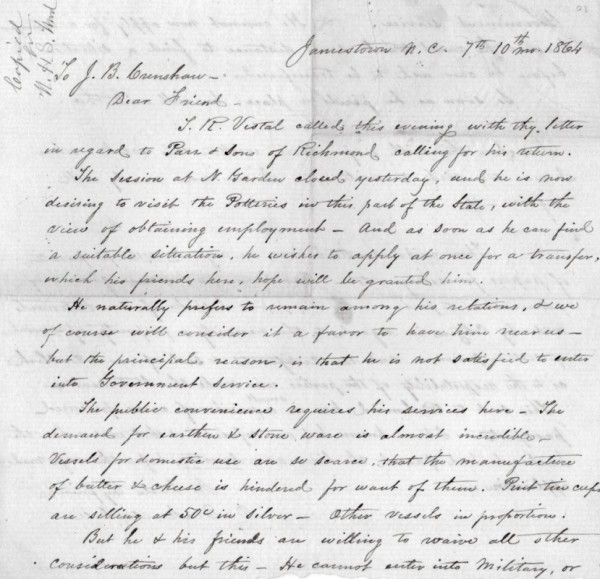

Letter from Delphina Mendenhall to J. B. Crenshaw, October 7, 1864. (Courtesy, Friends Historical Collection, Guilford College.) The letter describes the difficulty in acquiring pottery.

Fat lamp, attributed to the William Hockett/Hoggatt family of potters, northern Randolph/southern Guilford County, North Carolina, ca. 1860. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 4". (Private collection.)

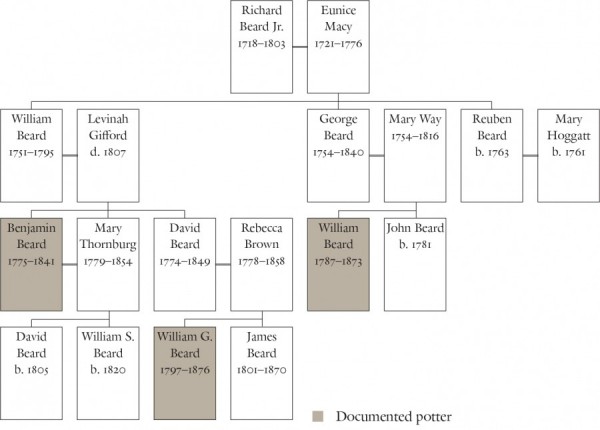

Beard Family of Potters. (Compiled by Hal Pugh and Eleanor Minnock-Pugh; artwork, Wynne Patterson.)

n Documented potter

Jar, Benjamin Beard, Guilford County, North Carolina, 1810–1830. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9 11/16". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Detail of the unusual pulled and pinched handle on the jar illustrated in fig. 52.

Detail of the impressed mark on the jar illustrated in fig. 52.

Deep River Friends Meeting, Deep River Community, Guilford County, North Carolina, 1873–1875. (Courtesy, Friends Historical Collection, Guilford College.) The meetinghouse was built using 133,000 bricks made of clay dug at Benjamin Beard’s land.