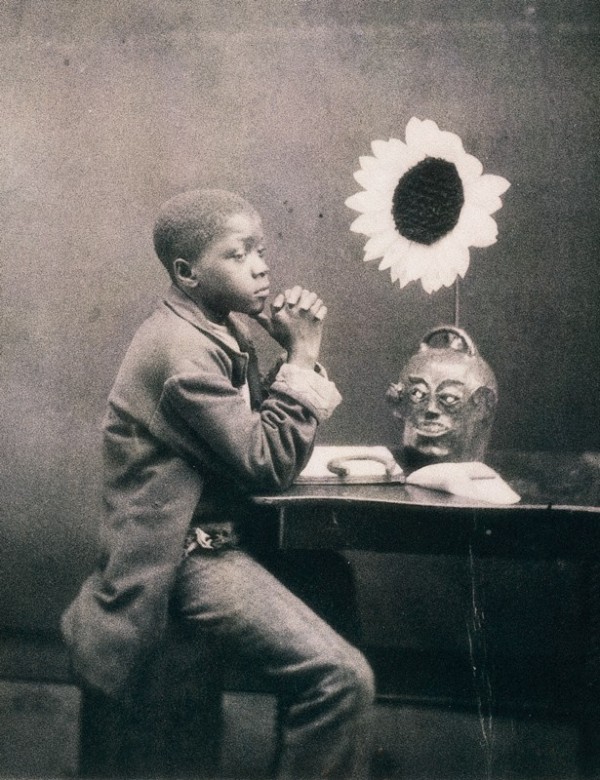

An Aesthetic Darkey, from a series of stereoscopic cards by photographer J. A. Palmer of Aiken, South Carolina, 1882. (Courtesy, J. Garrison Stradling.)

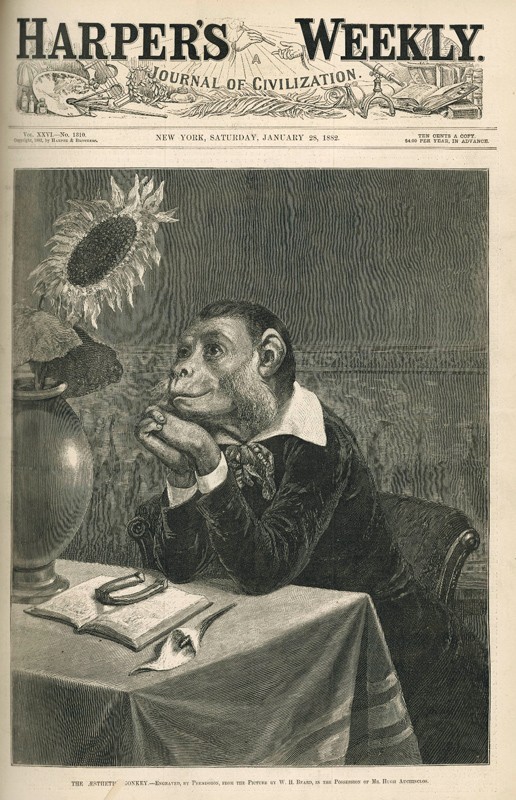

The Aesthetic Monkey, W. H. Beard, 1882. (Courtesy, Wisconsin Historical Society, whs-91892.) This image is a harsh, and possibly homophobic, visual satire of British writer and cultural commentator Oscar Wilde, who embarked on his North American tour in 1882.

Face jug, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1860–1870. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 7". (Courtesy, April Hynes; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Plumber Robert Strang discovered this jug in the 1950s in the Germantown section of Philadelphia, while digging a trench for the foundation and plumbing of the soon-to-be-built Leeds Middle School. The jug was buried at the site of a house that belonged to Leroy Stockton Wingate, who had two live-in servants from the Edgefield District. According to the 1930 U.S. Census, Lewis Gardner was Wingate’s chauffeur and Lewis’s wife, Leatha, was his cook. A World War I draft card for Lewis Gardner states that he was born in Edgefield. Genealogical records indicate that the Gardners’ ancestors were slaves at the plantation of Colonel Thomas J. Davies, a pottery owner interviewed by Edwin Atlee Barber in 1909. “Thomas Jones Davies Bible Records Transcription,” Thomas Jones Davies Bible Records, available online at http://digital.tcl.sc.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/davies/id/75/show/63/rec/19 (accessed March 12, 2013).

Face jug, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1860–1880. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 5 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Initially made by slaves and later by free African-Americans, early Edgefield face vessels are wheel-turned from stoneware clay and fired with alkaline glazes that range in color from sandy brown to olive green. The most distinctive feature of these objects is their highly expressive, applied face, which typically includes wide-open eyes, mouths with bared teeth, and idiosyncratic ears, noses, and eyebrows. On the earliest forms, the eyes and teeth are made from white kaolin clay, often left unglazed. Art historian Robert Farris Thompson notes that “the white . . . eyes and teeth, set against the glaze, make the finest Afro-Carolinian face vessels appear to roar where works three times their size merely whisper. . . . [N]othing in Europe [is] remotely like them, for the use of kaolin insets into the body seem[s] peculiar to the Afro-Carolinian and his imitators.” Robert Farris Thompson, “African Influence on the Art of the United States,” in William R. Ferris, ed., Afro-American Folk Art and Crafts (Boston: G. K. Hall, 1983), p. 39.

Face cup, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1860. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 4 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Face jug, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1860–1880. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 6". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Power figure (nkisi nkondi), Vili, Republic of the Congo, early- to mid-nineteenth century. Wood, metal, glass, fabric, fiber, cowrie shell, bone, leather, gourd, and feather. H. 28 1/4". (Courtesy, Ada Turnbull Hettle Endowment, 1998.502, The Art Institute of Chicago; photo © The Art Institute of Chicago.)

Postcard of a Kongo village with three minkisi (sing. nkisi) in foreground. Reproduced from Hans-Joachim Koloss, ed., Africa: Art and Culture (Munich: Prestel for the Ethnological Museum, Berlin, 2002), p. 126.

Photograph of a man sitting on a mat with a variety of minkisi. The image is stamped “Congo France” and dated October 20, 1909. Reproduced from Raoul Lehuard, Art BaKongo: Les centres de style, 2 vols. (Arounville, France: Arts d’Afrique Noire, 1989), 1: 81.

Power figure, Democratic Republic of the Congo. (Private collection; photo, Marc Felix.) The kaolin on this figure signifies the white skin of the dead.

Toby jug, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1785. Pearlware. H. 10". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Kongo terracotta head. (Courtesy, Royal Museum of Central Africa, Tervuren, Belgium, EO.1949.1.18; photo, J. Van de Vyver, © RMCA Tervuren.)

Face jug, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1860–1880. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 7 1/8". (Courtesy, New York Historical Society, 1937.141.)

Face jug, Lanier Meaders (American, 1917–1998), 1987. Glazed low-fired stoneware. H. 10". (Courtesy, Milwaukee Art Museum, Gift of Ruth and Robert Vogele, M2000.84.)

Face pitcher, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1860–1880. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, David B. Ward; photo, Jim Wildeman.)

Face jug, Thomas Chandler, Edgefield District, South Carolina, ca. 1850. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 11". (Private collection; photo, McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina.)

Two-face monkey-form jug, attributed to Henry Remmey Jr. or his son Richard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1858. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 11". (Ex-collection of Tony and Marie Shank; photo, Tony Shank.)

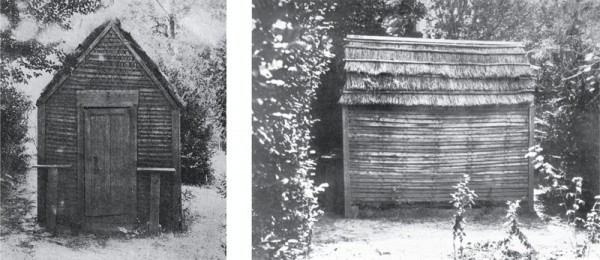

“Place where the pots of the deceased are kept,” photographed by Friedrich August Louis Ramseyer, Ghana, 1888–1908. 4 3/4 x 6 1/2". (Basel Mission Archives D-30.23.022; www.bmarchives.org/items/show/57131; photo, courtesy Basel Mission Archives.)

Ewe terracotta pots. Reproduced from Karl-Ferdinand Schaedler, Earth and Ore: 2500 Years of African Art in Terra-cotta and Metal (Eurasburg, Germany: Panterra Verlag, 1997), p. 191.

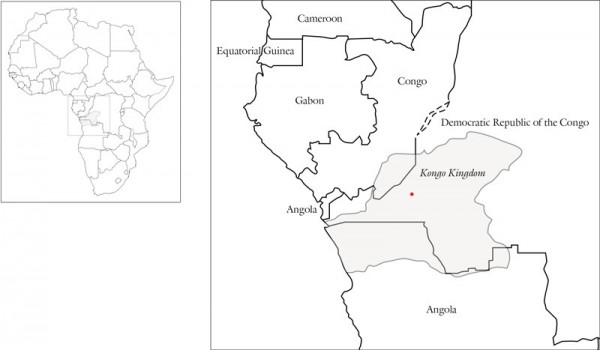

Map of Africa. Area in gray showing the Kingdom of Kongo, ca. 1850. Red dot indicates Madimba in the valley of the Mbidizi River in the Kongo Kingdom. (Map by Wynne Patterson.)

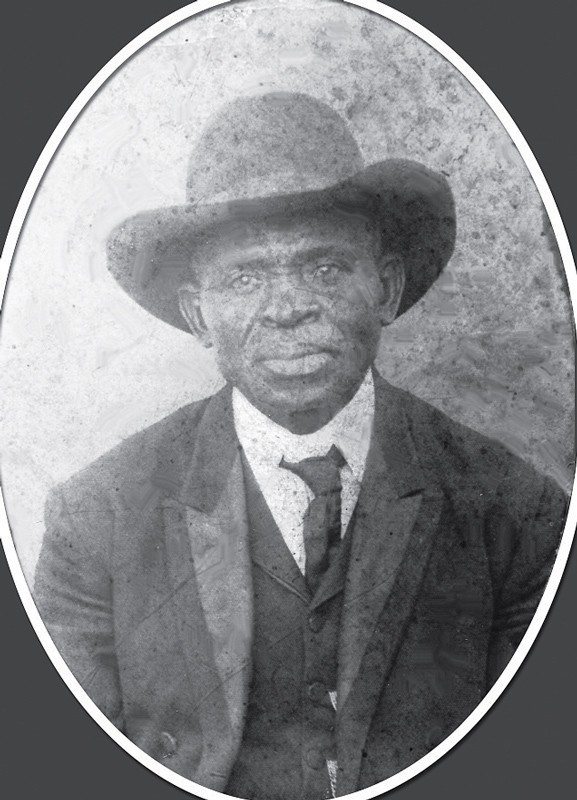

Photograph of Ward Lee, Edgefield County, South Carolina, ca. 1900. (Courtesy, Lee family.)

Face jug attributed to Ward Lee, Edgefield District, South Carolina, ca. 1880. Unglazed stoneware. H. 5". (Courtesy, Georgia Archeological Institute.)

Photographs showing the front and right side of the Romeo Thomas House, Edgefield District, 1908. Reproduced from Charles J. Montgomery, “Survivors from the Cargo of the Negro Slave Yacht Wanderer,” American Anthropologist, n.s., 10, no. 4 (1908): between pages 616–17 and 618–19.

“Catholic Priest Burning Idol House, Sogno, Kingdom of Kongo, 1740s,” reproduced from Paola Collo and Silvia Benso, eds., Sogno: Bamba, Pemba, Ovando . . . (Milan: Franco Maria Ricci, 1986), p. 163. (Photo, courtesy Biblioteca Civica Centrale di Torino.)

Diboondo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, ca. 1800. Terracotta. H. 17 11/16". (Courtesy National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, purchased with funds provided by the Smithsonian Collections Acquisition Program, 89-13-7; photo, Franko Khoury.)

Male and female divination figures, Baule, Côte d’Ivoire, nineteenth or early twentieth century. Wood, pigments, beads, and iron. H. of male 21 7/8"; H. of female 2 5/8". (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Gift of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1969, 1978.412.390, .391.)

Nkisi nkonde with tongue, Lekela Kongo (Yombe), Democratic Republic of Congo, 1913(?). (Courtesy, Coll. G. Rosselli-Lorenzini, Museo Nazionale Preistorico Etnografico “Luigi Pigorini,” inv. 84205; photo © S-MNPE “L. Pigorini” Roma EUR, courtesy MiBAC.)

Face jug, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1860–1880. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 4 1/2". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Jim Wildeman.)

Entry from 1900 U.S. Census, Schultz Township, Aiken, South Carolina.

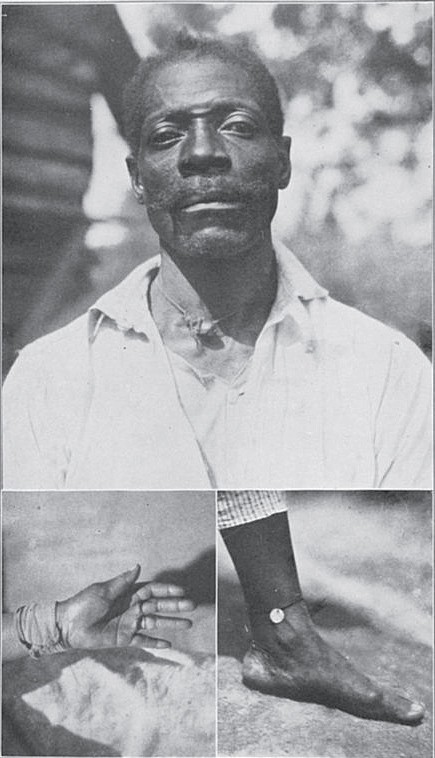

“Nutmeg, red flannel and silver,” in Newbell Niles Puckett, Folk Beliefs of the Southern Negro (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1926), between pp. 314–15. (Courtesy, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture / General Research and Reference Division.)

Face jug, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1860–1880. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 6 5/8". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the inscription on the back of the face jug illustrated in fig. 31.