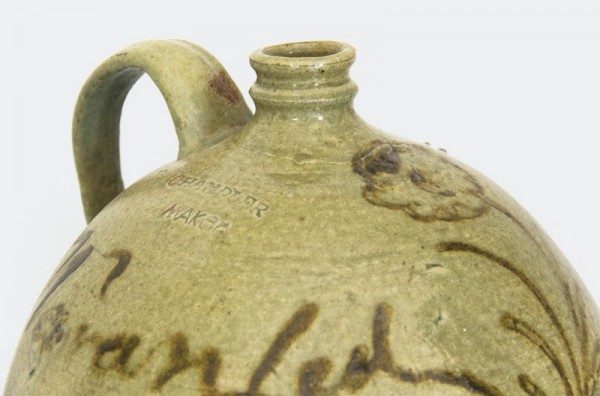

Detail of jug, Thomas Chandler, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1847–1852. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. Capacity mark: 3. Stamped mark: “CHANDLER MAKER” (Author’s collection; photo, Jan Todd.)

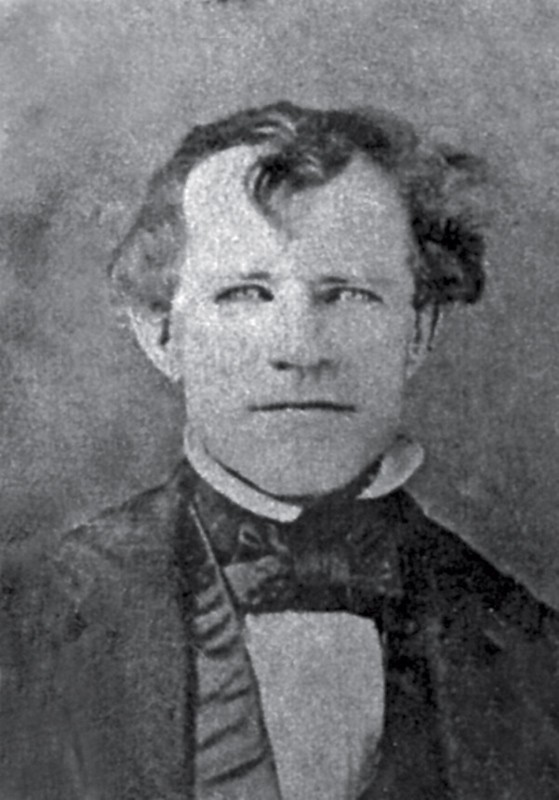

Daguerreotype of Thomas Chandler Jr., Edgefield District, South Carolina, ca. 1850. (Courtesy, William Robert Mathis, a direct descendant.)

Portrait of Elizabeth Wise Chandler, attributed to Joshua Johnson, ca. 1815, Accomack County, Virginia. Oil on artist board. 19 1/2 x 13 1/2". (Courtesy, Freeman’s Auctioneers and Appraisers, Philadelphia; photo, Elizabeth Field.) Elizabeth Wise Chandler was Thomas Chandler Jr.’s mother.

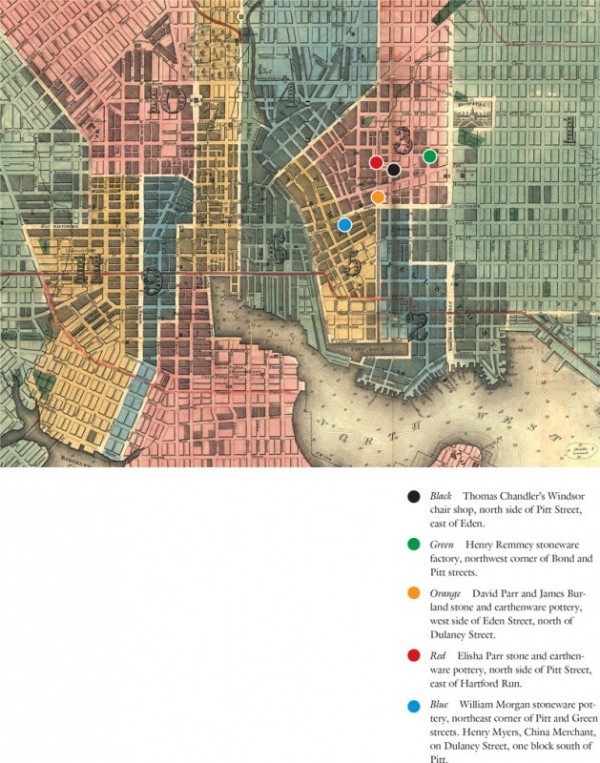

Plan of the City of Baltimore compiled from actual survey by Fielding Lucas Jr., 1822, improved 1836. (Courtesy, Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.)

Churn, Thomas Chandler Jr., likely Baltimore Stoneware Manufactory, Baltimore, Maryland, 1829. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14 1/2". Incised: “Mitchel · Chandler / 1829” (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The scene is believed to be the Mitchell Chandler homestead in Accomack. The handles, rim, and overall form are much like churns made by Henry Remmey while he was working for Henry Myers in Baltimore ca. 1825–1829.

Side views of the churn illustrated in fig. 5.

Incised inscription on the bottom of the churn illustrated in fig. 5: “Thomas M. Chandler / Maker / Baltimore August / 12 / 1829”

Storage jar, attributed to Thomas Chandler, Baltimore, Maryland, or possibly Richmond, Virginia, 1820s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14". (Author’s collection; photo, Jan Todd.)

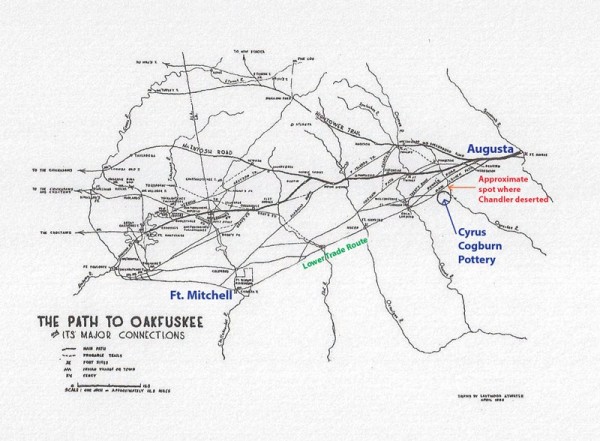

“The Path to Oakfuskee,” drawn by John H. Goff, reproduced in Georgia Historical Quarterly (March 1955): inserted between pages 4 and 5. The lower trade route between Augusta, Georgia, and Fort Mitchell, Alabama, is shown, with the parts pertinent to Thomas Chandler highlighted. The circle notates the proximity of the Cyrus Cogburn pottery to the lower trade path, which was used by the U.S. Infantry in March–April 1833. The arrow shows the approximate place of Chandler’s desertion. (Courtesy, Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library/University of Georgia Libraries.)

Detail showing production mark “C” on iron-slip alkaline-glazed stoneware jar from Edgefield District, South Carolina, attributed to Thomas Chandler, 1836–1840. (Author’s collection; photo, Jan Todd.) This mark is associated with Thomas Chandler at various production sites, but it has not been found in archaeology.

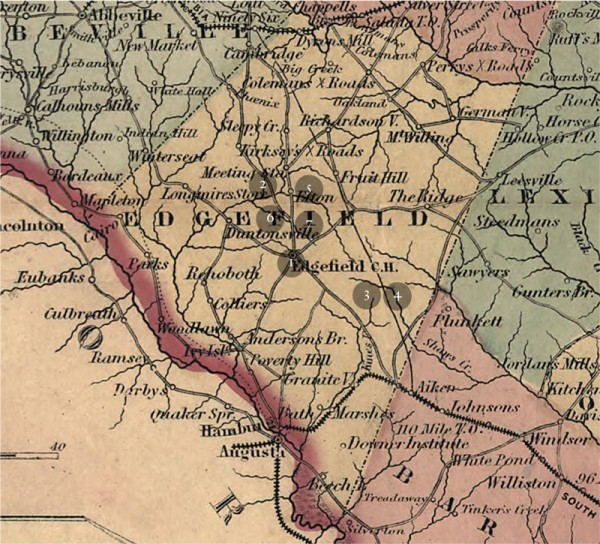

Sites of potteries where Thomas Chandler worked in the Old Edgefield District of South Carolina between 1835 and 1853, superimposed on J. H. Colton & Co.’s 1855 map of South Carolina.

1 38ED11, 1835–1837: Chandler appears to first work with Rueben Drake and Collin Rhodes at Pottersville.

2 38GN169, 1837–1838: Chandler is found working with John Isaac Durham north of Edgefield.

3 38AK495, early 1839: Chandler has moved to a site on Shaw’s Creek and begins experimenting with iron and kaolin slip decoration on alkaline-glazed pots.

4 38AK495, early 1840–1844: When Phoenix Factory is created as a partnership at Shaw’s Creek in early 1840, Chandler becomes primary turner and decorator of stoneware produced there. When the partnership dissolves in late 1840, Chandler remains at Shaw’s Creek until ca. 1844, likely working for Collin Rhodes. By 1844 he no longer turns pottery at site 38AK495, but decorates for Rhodes part time until about 1851.

5 38GN16, 1844–1848: It appears Chandler has opened and is working at “Chandler Site I.” This is near the Durham/Trapp/Chandler site 38GN169.

6 38GN169, 1848–1850: Chandler enters into partnership with John Trapp at the old Durham/Mathis pottery, now known as the Trapp/Chandler/Presley pottery, where he works for about two years.

7 38GN343, 1850: Chandler opens his second shop, “Chandler Site II,” about a mile south of site 38GN169 on the old Martintown Road. By 1853 it appears Thomas Chandler has left Edgefield and moved to Mecklenburg County, North Carolina.

Storage jar, John Landrum’s Horse Creek Pottery or Abner Landrum’s stoneware factory at Pottersville, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1821. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 11". (Private collection; photo, Jan Todd.) This represents some of the earliest alkaline-glazed ware from Edgefield.

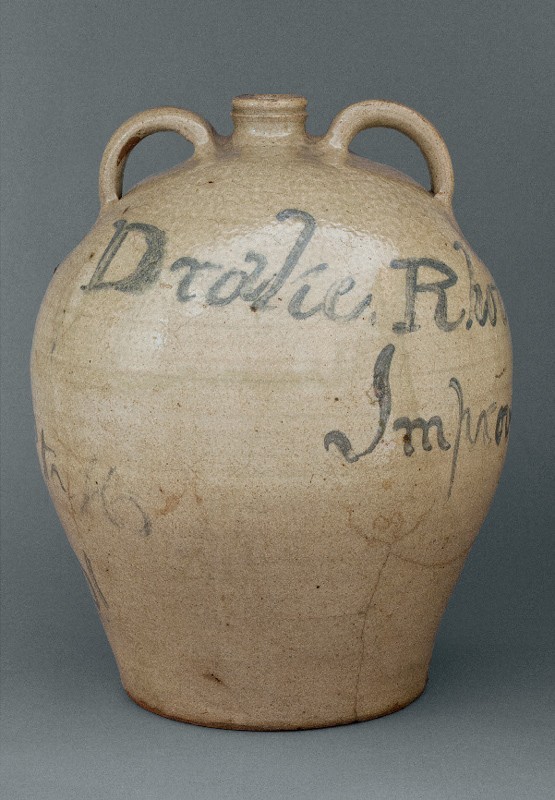

Two-handle jug, Rueben Drake and Collin Rhodes Pottery, Pottersville, South Carolina, 1836. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 17 1/2". Inscribed in cobalt: “Drake Rhodes & Co Improved Stoneware Edgefield Ct H S.C. 1836” (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Storage jar, Thomas Chandler Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1844. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 17 3/4". Inscribed in iron slip: “Chandler / Maker / 1844”; on reverse, in iron slip: “Mr. B. Harland” (Courtesy, Steve and Terry Ferrell; photo, Jan Todd.) The handwriting appears to be the same as that on the 1836 jug illustrated in fig. 13.

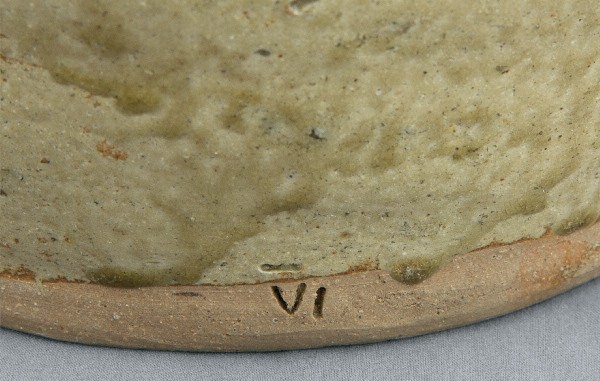

Detail of production/capacity mark, roman numeral VI. (Photo, Jan Todd.) This mark is attributed to Thomas Chandler at the Pottersville stoneware factory and the Trapp and Chandler Pottery location.

Detail of production/capacity mark roman numeral II. (Photo, Jan Todd.) This mark has been found at the pre–Trapp and Chandler site (38GN169).

Storage jar, detail of production mark oblate or elongated “C” near the rim, attributed to Thomas Chandler, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1835–1840 (38GN169). Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 13 1/2". Production/capacity mark near base: “II” (see fig. 16). (Author’s collection; photo, Jan Todd.)

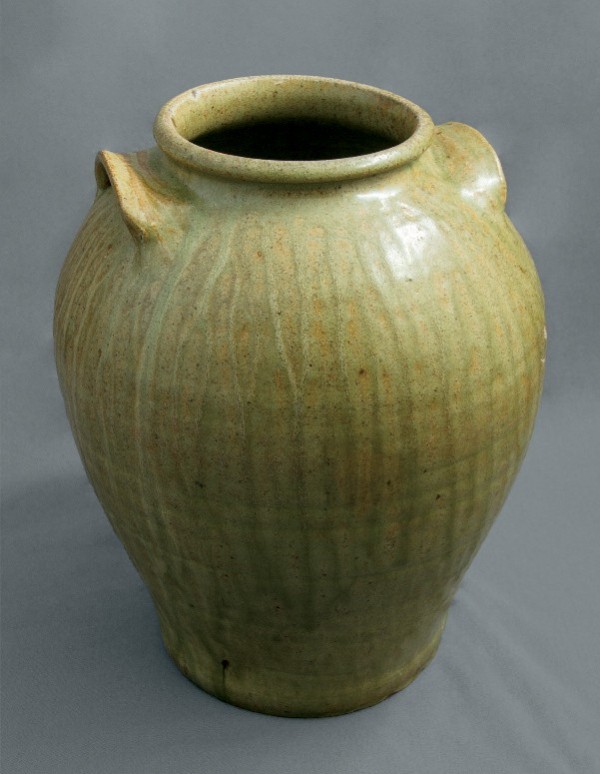

Storage jar, attributed to Thomas Chandler, Edgefield District, South Carolina, ca. 1837. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 16". Production/capacity mark at base: “VI” (see fig. 15). (Author’s collection; photo, Jan Todd.)

Storage jar, attributed to Thomas Chandler or John Isaac Durham, Edgefield District, South Carolina (site 38GN169), ca. 1837. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 12 1/2". Stamped capacity mark near base: “II” (see fig. 16). (Author’s collection; photo, Jan Todd.)

Storage jar, attributed to Thomas Chandler, Edgefield District, South Carolina (site 38GN169), ca. 1837. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 11 1/2". Production mark: oblate or elongated “C” (see fig. 17); production/capacity mark near base: “II” (Author’s collection; photo, Jan Todd.)

Storage jar, attributed to Thomas Chandler, Edgefield District, South Carolina (site 38GN169), ca. 1837. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 13 1/2". Production/capacity mark: “III” partially filled in with glaze. (Author’s collection; photo, Jan Todd.) In this surviving example, Chandler had begun to transition his glaze toward celadon.

Detail of the production/capacity mark “II” on the jar illustrated in fig. 20.

Storage jar, attributed to Thomas Chandler, Edgefield District, South Carolina, ca. 1837. Iron-slip alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 10". Three small “C”s are impressed equidistant around the rim and three additional roman numeral marks are at the base (see fig. 10); compare with the mark on the jug illustrated in fig. 24.

Spirits jug, attributed to Thomas Chandler, Phoenix Factory, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1840. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 16 3/4". Impressed mark: “PHOENIX FACTORY ED: SC / C” (Courtesy, Collection of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Jar, Shaw’s Creek Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1837–1839. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 9 1/4". (Author’s collection; photo, Jan Todd.) Chandler adapted and developed the swag-and-tassel decoration from the Remmey family of potters of New York and Baltimore; this is one of his first examples decorated with iron slip.

Storage-jar fragments, Shaw’s Creek Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1837–1839. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Steve and Terry Ferrell; photo, Jan Todd.) These fragments, found by ceramics historian Steve Ferrell at Shaw’s Creek, exhibit slip-trailed decoration that is remarkably similar to the delicate swag-and-tassel decoration in cobalt on the salt-glazed stoneware jar illustrated in fig. 8. See also fig. 38.

Stew pot, Shaw’s Creek Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1837–1839. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 8". (Courtesy, Randy Windham; photo, Jan Todd.) This early stew pot presents iron-slip decorative elements that are some of the first developed by Chandler in Edgefield. One can see from this example that Chandler had not yet developed the right liquid consistency for his decorative slip.

Storage jar, Thomas Chandler, Phoenix Factory, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1840. Alkaline-glazed stoneware with brushed iron-slip decoration. H. 19 1/4". Incised: “Phoenix Factory”; “1840” (Courtesy, Steve and Terry Ferrell; photo, Jan Todd.) Compare the iron-slip brushed flowers between the handles on this example to the cobalt trailed flowers on the jar illustrated in fig. 8.

Storage jar, attributed to Thomas Chandler, Shaw’s Creek/Phoenix Factory area, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1841–1845. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 16 3/4". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) With a shape more bulbous than ovoid, this approximately ten-gallon storage jar was likely produced after Phoenix Factory had dissolved. Based on the large volume of waster material at Phoenix Factory, it appears that Chandler continued potting at the site under the auspices of Collin Rhodes.

Storage jar, Edgefield District, South Carolina, ca. 1845. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 14 1/2". (Courtesy, Vivian and Gerald Gowitt; photo, Jan Todd.) In my opinion this example was made at the first site Chandler operated independently (38GN16), near Trapp and Chandler (38GN169). The iron-trailed sprigs match potsherds found at site 38GN16.

Storage jar, Thomas Chandler Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1845–1850. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 12 1/2". (Courtesy, Doug and Brenda Howard; photo, Louis Tonsmeire Studio.) Thomas Chandler began using two-color slip decoration and elaborated on the swag-and-tassel theme by 1840 while at Phoenix Factory. The design on this example is almost identical to the design on the jar illustrated in fig. 25, but the outline in white slip makes a bolder, more neoclassical statement.

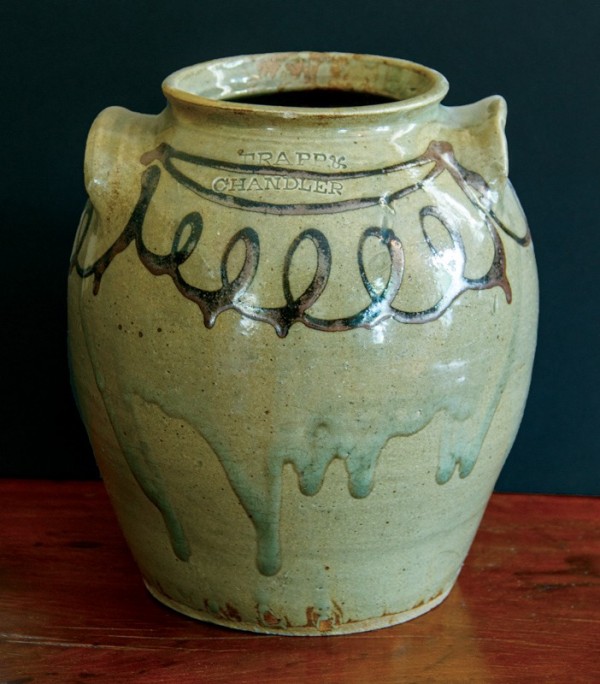

Storage jar, Trapp and Chandler Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1848–1850. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 11 1/2". Impressed mark: “TRAPP & CHANDLER” (Courtesy, L. C. Lynch; photo, Jan Todd.) By 1848 Chandler was using draped lines with loops beneath, in iron or kaolin slip, as his primary decorative motif. The thick yet translucent celadon overglaze makes a stunning presentation.

Buttermilk pitcher, possibly eastern Texas, 1860–1870. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 8 1/2". (Courtesy, John Lafoy; photo, Jan Todd.) One of the few slip-decorated stoneware examples surviving from the post-Chandler era, ca. 1860. After Chandler’s death, in 1854, only a handful of slip-decorated Southern stoneware examples were produced by potters in South Carolina or points west.

Mixing pan, William Morgan Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1825. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 6 3/4". (Courtesy, Crocker Farm Auction.) The squared pouring spout and the slab handles were adapted by Thomas Chandler. Compare the zigzag decoration to that on the jug illustrated in fig. 24.

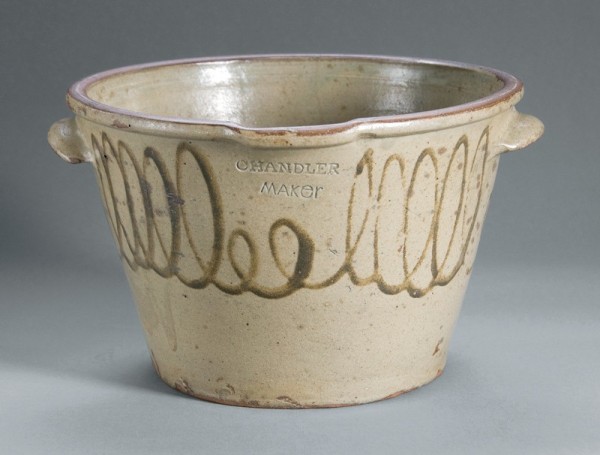

Mixing pan, Trapp and Chandler Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1848–1850. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 7 1/4". Impressed mark: “CHANDLER MAKER”(Collection, Doug and Brenda Howard; photo, Louis Tonsmeire Studio.) Squared pouring spouts are commonly seen on Baltimore stoneware; they were not made in Edgefield prior to Chandler’s arrival.

Stoneware wasters, Thomas Chandler Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1840. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, University of South Carolina, McKissick Museum; photo, Carl Steen.) Archeologist Carl Steen found these collapsed vessels on top of the waster at the Thomas Chandler Pottery during a survey in 1988.

Storage jar, attributed to Thomas Chandler, Phoenix Factory, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1840. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Dr. and Mrs. John Hoar; photo, Brewster Photography). A magnificent surviving example of Chandler’s work at Phoenix Factory. Here the kaolin is applied with a brush instead of a slip cup.

Storage jar, attributed to John Remmey III, New York or New Jersey, 1810–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9". (Courtesy, Bruce and Vicki Waasdorp, American Pottery Auction.) This decoration matches the decoration on the Phoenix Factory jar illustrated in fig. 37.

Pitcher, Baltimore Stoneware Manufactory, Baltimore, Maryland, 1825–1828. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 10". Stamped: “BALTIMORE, / H. REMMEY” (Courtesy, Crocker Farm Auction.) The cobalt-trailed floral decoration is the same basic design that Chandler would use some twenty years later.

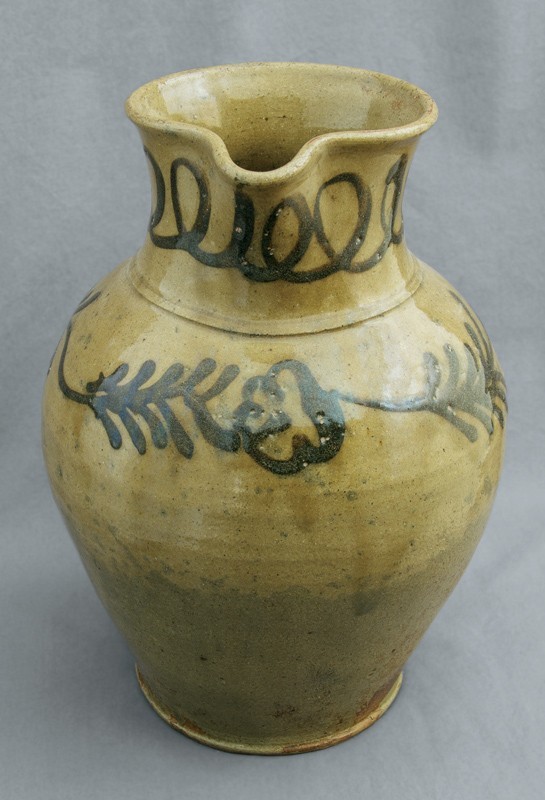

Pitcher, Trapp and Chandler Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1848–1850. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 13 1/2". (Courtesy, Donny Taylor; photo, Jan Todd.) This wonderfully executed sprig-and-flower-head decoration is a Chandler adaptation of Henry Remmey’s design in Baltimore.

Detail of mark on a storage jar, David or Elisha Parr Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, 1820–1830. Salt-glazed stoneware. Capacity mark, stamped within a circle of coggle-impressed teeth: “3” (Author’s collection; photo, Jan Todd.)

Spirits jug, Thomas Chandler Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1850–1852. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 16". Capacity mark: “3”; stamped signature: “CHANDLER / MAKER” (Author’s collection; photo, Jan Todd.) Chandler developed his own technique for indicating capacity by evolving the coggled circle on the jar illustrated in fig. 41 into a large, slip-cup-executed cartouche surrounding a slip-drawn freehand arabic numeral. In some instances he framed the capacity with a daisy flower head instead of a cartouche. This was done in a kaolin or iron slip. After 1840 Chandler used this method to indicate gallons, as he no longer marked his ware with roman numerals, slashes, capacity stamps, or incised arabic numerals. This is in stark contrast to his contemporaries, who continued to use slashes, punctuates, crosses, and dots to indicate gallons until the 1860s.

Jug, Collin Rhodes Stoneware Factory, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1844–1851. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 15 1/2". Capacity mark: “3” (Courtesy, Sam Phillips; photo, Jan Todd.) This jug was decorated by Chandler, who decorated virtually all of the ware produced at this pottery. Note the capacity surrounded by a daisy flower head.

Storage jar, attributed to Thomas Chandler, Shaw’s Creek Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1839. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 17". Inscribed in slip: “Shaws Creek / Pottery / 1839” (Courtesy, Sam Phillips; photo, Jan Todd.) This is an early example of a Chandler presentation piece, bearing a type of flower decoration he used primarily for Collin Rhodes. The sprigs, bell flowers, and daisy heads are all Baltimore-influenced Chandler designs. The writing is in his hand. This establishes that Chandler had mastered the art of slip decoration on alkaline-glazed stoneware by 1839.

Water cooler, attributed to Thomas Chandler, Phoenix Factory, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1840. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 31 1/4". Stamped: “PHOENIX FACTORY ED:SC” on reverse. (Courtesy, High Museum of Art, Purchase in honor of Audrey Shilt, President of the Members Guild, 1996–1997, with funds from the Decorative Arts Endowment and Decorative Arts Acquisition Trust.) This mammoth water cooler was possibly a presentation to slaves in the Chandler household. The drawing on this surviving example is very similar to the drawing on the Chandler Baltimore churn illustrated in figs. 5–7.

Detail of the water cooler illustrated in fig. 45, showing the scratch decoration of the facing slaves. Compare the hands and facial features with the incising of the Baltimore churn illustrated in fig. 5.

Storage jar, Trapp and Chandler Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1845–1850. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 29". (Courtesy, Sam Phillips; photo, Jan Todd.) This massive jar with an agglutinated glaze and four handles has an unusual double-rolled rim, apparently adopted by Chandler from his time working with Remmey in Baltimore.

Water cooler, Baltimore Manufactory, Baltimore, Maryland, 1821–1829. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15". Impressed mark: “H. Myers” (Courtesy, Crocker Farm Auction.) Attributed to Henry Remmey while he was working for Henry Myers. The unusual double-rolled rim was adapted by Chandler and used by him sporadically in the Edgefield District.

Detail of a storage jar, Thomas Chandler Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1850–1852. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. Stamped on the shoulder: “FLINT WARE” (Courtesy, L. C. Lynch; photo, Jan Todd.) Stamped “flint ware” examples are some of the highest-fired stoneware made by Chandler.

Jug, Thomas Chandler Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1850. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 19". Inscribed in dark slip on shoulder: “Waranted”; “1850”; and “5” within a cartouche; stamped: “CHANDLER MAKER” (Courtesy, L.C. Lynch; photo, Jan Todd.) This five-gallon spirits jug is decorated with the Chandler daisy flower head.

Water cooler, Thomas Chandler Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1852. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 20". Stamped: “CHANDLER MAKER” (Courtesy, Steve and Terry Ferrell; photo, Jan Todd.) This approximately fifteen-gallon vessel displays a delicate slip-trailed kaolin decoration as well as a classic celadon glaze. The sprig-and-flower-head decorations on this piece are nearly identical to those on the jar illustrated in fig. 44 right, which were executed some thirteen years earlier.

Harvest face vessel, Thomas Chandler, Edgefield District, South Carolina, ca. 1845. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 11". Stamped on reverse, near center top beneath handle: “CHANDLER / MAKER” (Private collection; photo, Philip Wingard.) The bell handle, nipple spout, and double-collar spout, not to mention the facial expression, are distinctive. I believe this was Chandler’s personal drinking jug, and remained in his possession until his death.

Reverse side of the harvest face vessel illustrated in fig. 52. (Photo, Philip Wingard.)

Face-vessel fragment, Phoenix Factory, Edgefield District, South Carolina, ca. 1840. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Steve and Terry Ferrell; photo, Dr. John Hoar.) The true-to-life eyes are like those executed on other face vessels of 1838–1852 by Thomas Chandler. In the Edgefiield District, no fragments or surviving face vessels from a period prior to 1838 are known to exist. Chandler brought the idea of the face vessel with him, having learned about the form while in Baltimore, most likely from Henry Remmey.

Face vessel, attributed to the Phoenix Factory, Edgefield District, South Carolina, ca. 1840. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 9 1/4". (Courtesy, Dr. and Mrs. John Hoar; photo, Dr. John Hoar.) This face vessel was recovered from the marsh of the Charleston harbor in the 1920s. Based on the archaeology from site 38GN169, where Chandler worked prior to Shaw’s Creek and Phoenix Factory, dipping large sections of vessels in a contrasting iron wash was being done at this Martintown Road site. This decorative technique was first developed here by Chandler and others prior to their arrival at Shaw’s Creek.

Face harvest vessel, attributed to the Trapp and Chandler Pottery, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1845–1848. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 8 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Carl Steen.) The nose, mouth, and eyes are very similar to those on the signed Chandler example illustrated in fig. 52. Also shared are the small nipple spout and double-collar spout. There is applied iron wash at the base of the missing bail handle.

Face jug, Trapp and Chandler Pottery or possibly Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, attributed to Thomas Chandler, 1848–1854. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 10 1/4". (Courtesy, David Good; photo, Carole Wahler.) Traces of blue rutile, a characteristic of alkaline-glazed North Carolina stoneware, and the darker clay body and glaze indicate that this jug might have been made in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, during Chandler’s short tenure there.

Face harvest vessel, Baltimore, Maryland, 1825–1829, Chandler school. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 10 1/8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg, Abby Aldrich Folk Art Museum.) There are at least three known lead-glazed earthenware face harvest vessels made by the same potter. That these vessels have facial features very closely related to the known signed Chandler example, as well as the four unsigned stoneware examples attributed to Chandler, suggests that they were likely made in Baltimore and that Chandler either made them or was trained by the potter who did.

Face harvest vessel, Chandler school, Baltimore, Maryland, 1825–1829. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 9". (Courtesy, David Good; photo, Carole Wahler.) This example has a strong provenance to Baltimore.

Face harvest vessel, Edward Stone Pottery, Buncombe County, North Carolina, 1860–1870. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 9". Stamped: “J. H. Stone” (Courtesy, Donnie Garrett; photo, Jan Todd.) James Henry Stone, son of Edward Stone, was born in Buncombe County in 1847.