Left: Ivor Noël Hume and Michelle Erickson. (Unless otherwise noted, all photos by Robert Hunter.) Right: Jacqui Pearce (photo, courtesy of the author).

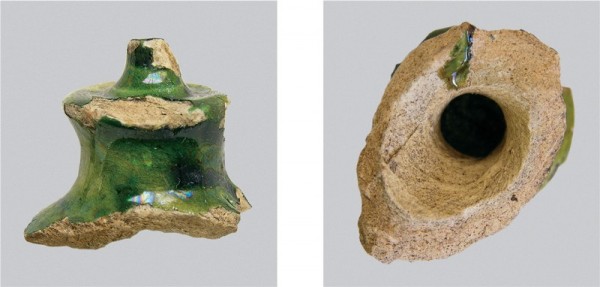

Money box, Surrey/Sussex, England, 1560–1620. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 3 1/2". (Courtesy, Noël Hume Collection.) This shows the enigmatic hole in the shoulder of the green-glazed Border Ware money box. The lower side of the body has been restored.

Money boxes from London’s old Guildhall Museum Collection. Left: miter-shaped, probably from Cheam, Surrey, England, late medieval, lead-glazed earthenware; center, right: green-glazed Border Ware, Surrey/Sussex, England, 1560–1620. H. of money box on right 3 15/16". (Courtesy, Museum of London; photo, Ivor Noël Hume.)

Money box, probably Cheam, Surrey, England, ca. 1500. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 3 1/2". (Courtesy, Noël Hume Collection.) The coin slot of this miter-shaped money box measured 1 1/4 x 1/16" before it was widened.

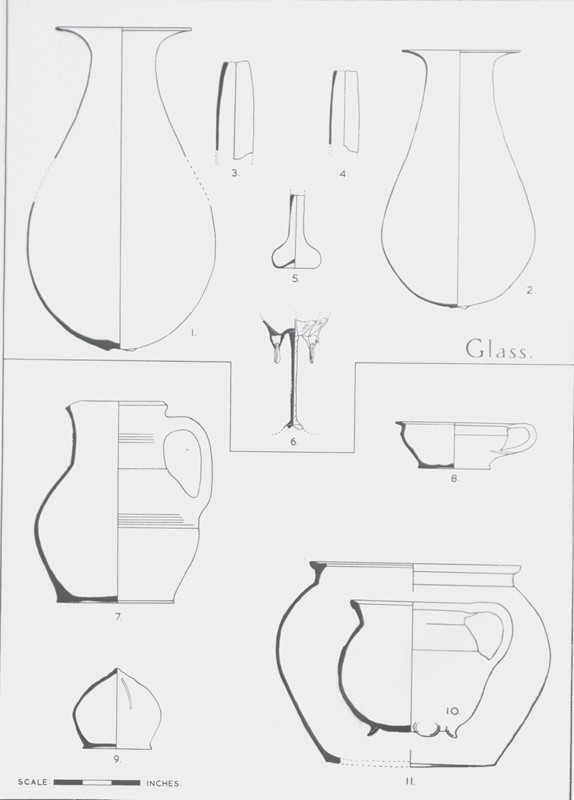

Drawing of a Border Ware pitcher and miter-shaped money box found in a closely datable London refuse pit, 1480–1510. (Courtesy, Guildhall Museum Collection; artwork by Ivor Noël Hume.)

Money box, Farnborough, Hampshire, England, 1565–1580. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 3 1/2". (Courtesy, Guildford Museum; photo, Jacqui Pearce.) This Border Ware money box is a waster found in a kiln flue (No. 3) on the Farnborough Hill site.

Button-knopped reproduction money box showing its documented method of suspension.

The shaft of an Elizabethan pin snuggly fits the mystery hole on the money box illustrated in fig. 2.

Piercing the hole into the wet clay and cutting the coin slot when leather hard.

Fired fragments show the different impacts of piercing the wet clay and cutting the slot at the leather-hard stage.

Lead-glazed knop fragment from The Theatre, Shoreditch (1576–1598), site reveals glaze bleeding through the concealed pinhole. (© Museum of London Archaeology; photo, Tim Braybrooke.)

Turning the button knop and trimming the base before drying.

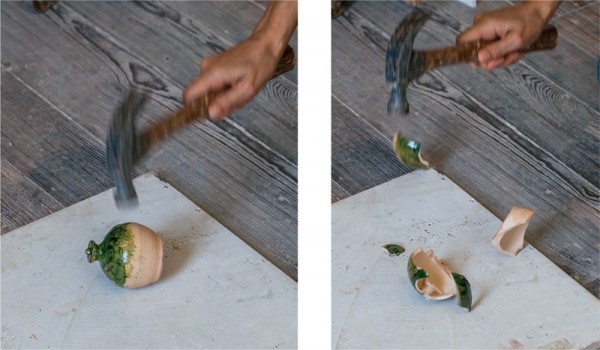

One method of opening the (reproduction) box.

The hammer crew.

Unfired reproductions show concave (left) and flat (right) bases.

The white arrow points to the scar on the period money box, which provided a clue to the method of kiln stacking.

Tiny lumps on the base of the period money box showed that it had stood on top of another, separated by a trivet-style stilt.

Money box, Donyatt, Somersetshire, England, 1828. Slipware. H. 4", slot length 1 1/2", slot width 3/16". Inscription: E B R / May 21 / 1828. (Courtesy, Jacqui Pearce.) This pin-pierced Donyatt sgraffito slipware money box is the earliest dated example yet recorded from that Somersetshire factory.

Pinhole revealed on the interior of the ca. 1800 brown stoneware money box illustrated in fig. 27.

Money box, London, England, ca. 1650. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 6 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Alan Tabor, Robert Woolley Ceramics & Works of Art.)

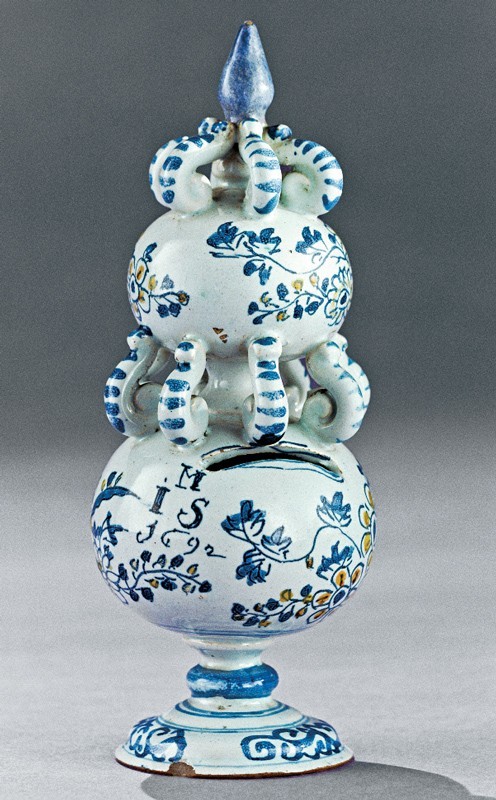

Money box, London, England, 1692. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 7 3/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg.)

Money box, Donyatt, England, 1905. Slipware. H. 6"; slot 1 3/4 x 1/4". Sgraffito inscription: “Ralph Coles / Xmas / 1905.” (Courtesy, Noël Hume Collection.)

Money box, northern Netherlands, 1600s–1700s. Lead-glazed and white-slipped redware. H. 3 1/2"; slot 1 1/2", width damaged. (Courtesy, Noël Hume Collection.) This pedestal-based money box has been restored.

Money box, Normandy, France, 1600s. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 4 3/8"; slot 1 1/4 x 1/8". (Courtesy, Noël Hume Collection.) This button-knopped, green-glazed, white-bodied money box has a pedestaled foot and vertical coin slot. It is believed to be Norman French in the English style.

Testing coin receptivity of the money box illustrated in fig. 2 shows that its slot will accept neither a 1607 James I shilling nor a 1566 Elizabethan sixpence.

An undated Elizabethan silver penny is of the size that the money box illustrated in fig. 2 will accept, which was the price of admission to The Rose, where most of London’s boxes were found.

Money boxes, Derbyshire, England, 1800s. Brown stoneware. Left: H. 6 1/4"; slot 1 3/4 x 1/4"; right: H. 4 1/2". (Courtesy, Noël Hume Collection.) The slots of these examples were made to receive George III twopences (left) and pennies (right), which were issued only at the Soho mint in 1797.

The 1806 return to numismatic normalcy inspired a century and more of turned and molded but nonpinholed money boxes. H. of Staffordshire dog 4 1/4". (Courtesy, Noël Hume Collection.)