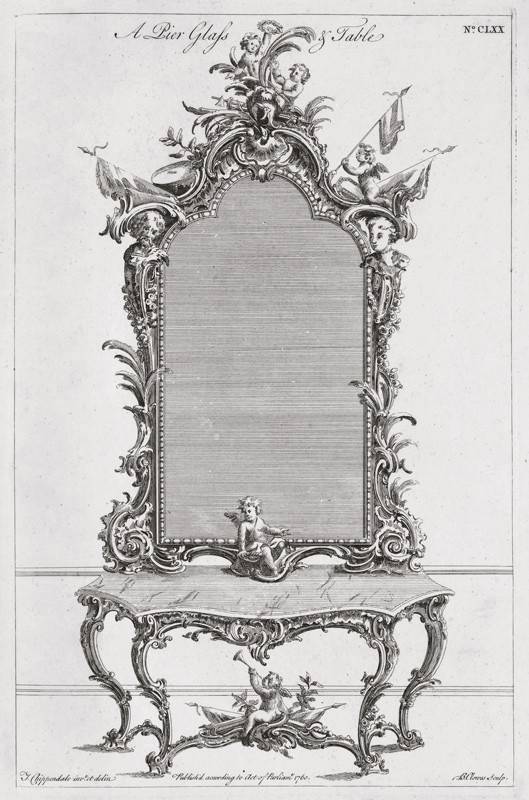

Plate 170 in the third edition of Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1762). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) This plate does not appear in the 1754 and 1755 editions.

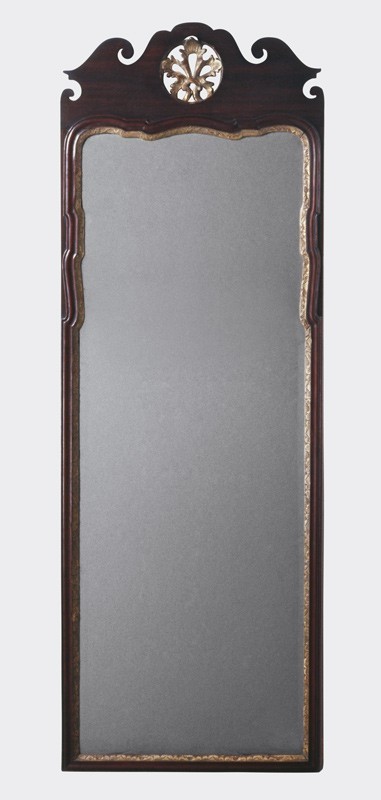

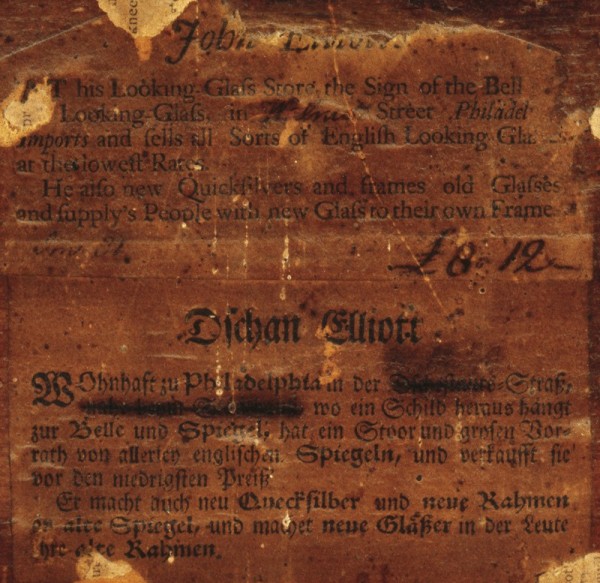

Looking glass bearing the label of John Elliott, England, ca. 1765. Mahogany with spruce and scots pine. 57" x 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) The label on this looking glass is in English and German.

Looking glass bearing the label of John Elliott, England, ca. 1765. Mahogany with spruce and scots pine. 57" x 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) The label on this looking glass is in English and German.

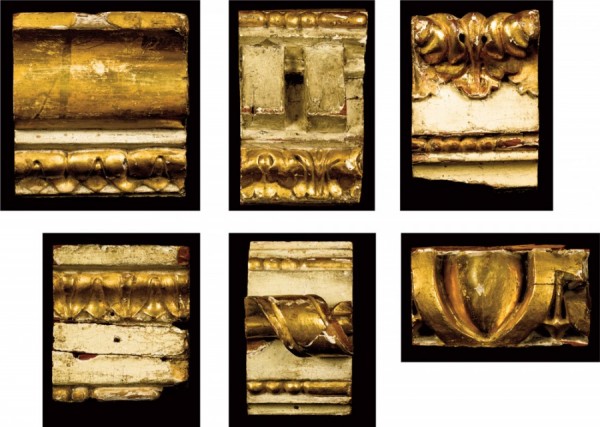

John Singleton Copley, Ezekiel Goldthwait, Boston, Massachusetts, 1771. Oil on canvas, 50 1/8" x 40". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, bequest of John T. Bowen in memory of Eliza M. Bowen.) The frame is attributed to Boston carver John Welch.

Detail of the carving on the frame illustrated in fig. 3.

Looking glass attributed to John Welch, Boston, Massachusetts, 1775–1790. Mahogany and white pine (gilded components) with white pine. 43 1/2" x 19 1/2". (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

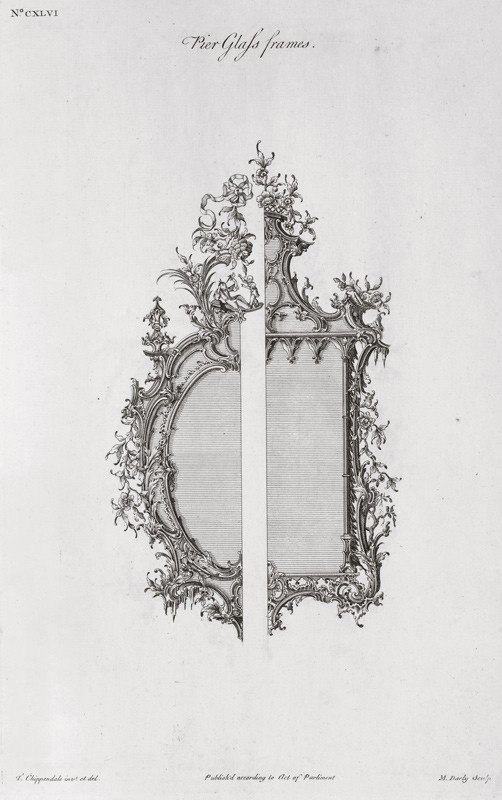

Plate 146 in the first and second editions of Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1754, 1755). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Desk-and-bookcase, Boston, Massachusetts, 1770–1790. Mahogany with cherry and white pine. H. 98 1/2", W. 47 1/4", D. 24 3/4". (Courtesy, Historic New England, gift of Elizabeth Inches Chamberlain in memory of her father, Henderson Inches; photo, Richard Cheek.)

Detail of the bird ornament on the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 7.

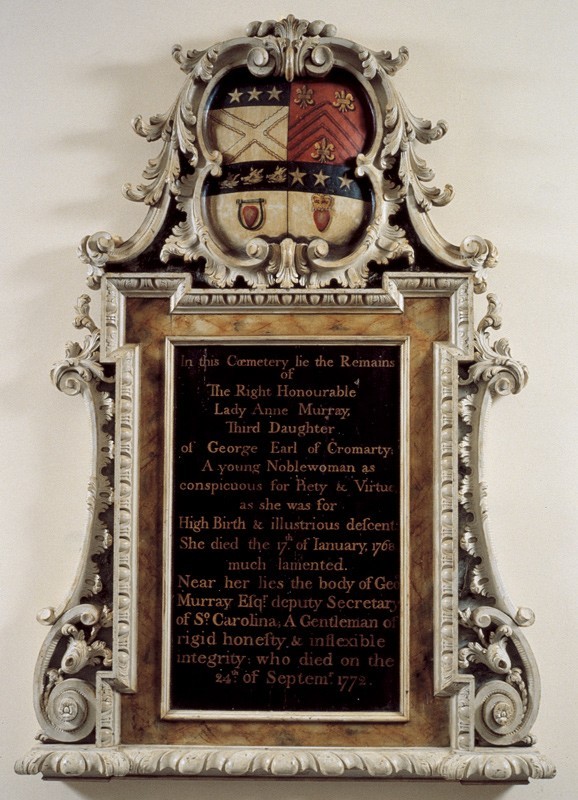

Memorial to Lady Anne Murray, attributed to John Lord, Charleston, South Carolina, 1768–1772. White pine. 73 1/2" x 51 1/4". (Courtesy, First Scots Presbyterian Church; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) As is the case with this memorial, some eighteenth-century looking glasses were painted in imitation of stone.

Looking glass attributed to John Pollard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770–1780. Mahogany with white pine. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Comparative illustration showing (left) the garland on the right side of the looking glass illustrated in fig. 10, (right) a garland from the parlor of the Thomas Ringgold House in Chestertown, Maryland. (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.) All of the carving in the Ringgold House is attributed to John Pollard. Eighteenth-century patrons occasionally commissioned the same tradesman to furnish both furniture and architectural carving. Although there is no evidence that Thomas Ringgold owned this looking glass, its garlands and those in his house show how harmonious the visual interplay between furniture and architectural carving could have been.

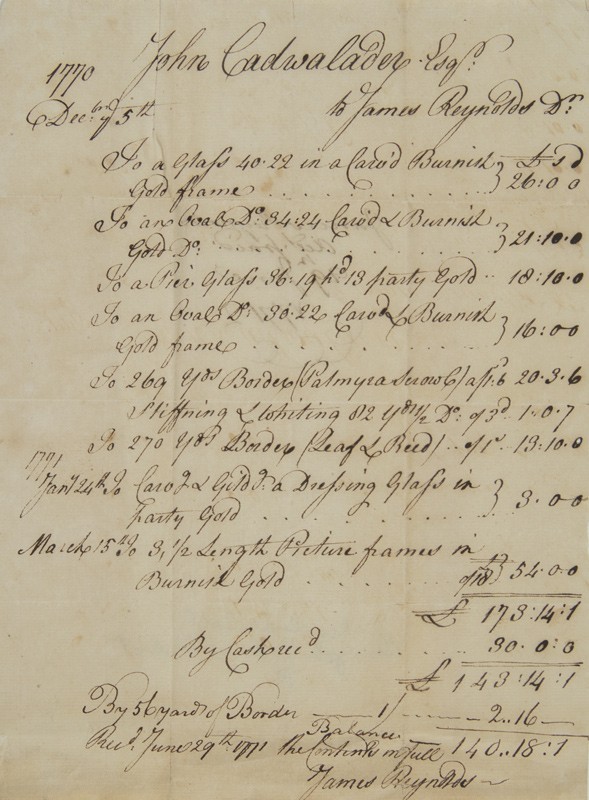

Bill from James Reynolds to John Cadwalader for work performed between December 5, 1770, and March 15, 1771. (Courtesy, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.)

Pier glass attributed to the shop of James Reynolds, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770–1771. White pine with tulip poplar. 55 1/2" x 28 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Detail of the iron armature on the back of the pier glass illustrated in fig. 13.

Detail of the upper left corner of the pier glass illustrated in fig. 13. Reynolds applied three coats of relatively coarse gesso to the frame. The entire gesso zone is off-white in color with a gradation from dark to light. This may indicate a reduction in the percentage of glue used in the second and third coats.

Pier glass attributed to the shop of James Reynolds, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1766–1775. White pine. 60 1/2" x 30 1/4". (Courtesy, Cliveden, a co-stewardship property of the National Trust for Historic Preservation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The sides of the Fisher and Cadwalader frames appear to have been laid out with the same pattern (figs. 13, 16, 17).

Comparative illustrations showing, from left to right, the lower right corner of the pier glass illustrated in fig. 13 and the lower right corner of the pier glass illustrated in fig. 16. Patterns typically transferred only the basic outlines of carved detail, which accounts for variations within and between these looking glass frames. After laying out the carving on one side, Reynolds simply flipped the pattern to lay out the other side.

Pier glass attributed to the shop of James Reynolds, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1766–1775. White pine. 48" x 26". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Pier glass attributed to the shop of James Reynolds, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, probably 1772. White pine. 78" x 42". (Courtesy, Cliveden, a co-stewardship property of the National Trust for Historic Preservation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This glass is one of a pair.

Girandole attributed to the shop of James Reynolds, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, probably 1772. White pine. 38 1/2" x 23 1/4". (Courtesy, Cliveden, a co-stewardship property of the National Trust for Historic Preservation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The branches are missing. Their original place of attachment corresponds with the oval element above the opposing C-scrolls at the bottom of the frame.

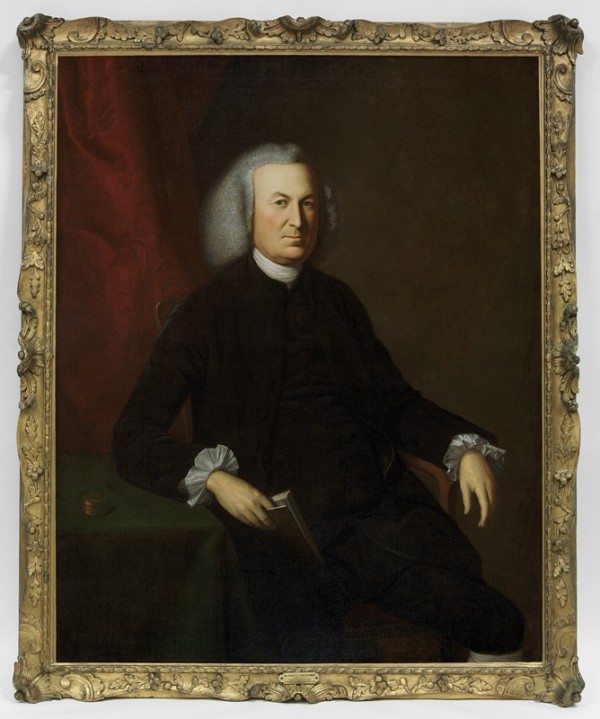

Charles Willson Peale, Thomas Cadwalader, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770. Oil on canvas. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; purchased for the Cadwalader Collection with funds contributed by the Mabel Pew Myrin Trust and the gift of an anonymous donor, 1983.) The frame is attributed to the shop of James Reynolds and measures approximately 60" x 50". All four sides have had their outer edges altered. This example is one of the three “1/2 Length Picture frames in Burnish Gold” listed in the bill illustrated in fig. 12.

Charles Willson Peale, Hannah Cadwalader, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770. Oil on canvas. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; purchased for the Cadwalader Collection with funds contributed by the Mabel Pew Myrin Trust and the gift of an anonymous donor, 1983.) The frame is attributed to the shop of James Reynolds and measures approximately 60" x 50". All four sides have had their outer edges altered. This example is one of the three “1/2 Length Picture frames in Burnish Gold” listed in the bill illustrated in fig. 12.

Charles Willson Peale, Lambert Cadwalader, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770. Oil on canvas. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; purchased for the Cadwalader Collection with funds contributed by the Mabel Pew Myrin Trust and the gift of an anonymous donor, 1983.) The frame is attributed to the shop of James Reynolds and measures approximately 60" x 50". All four sides have had their outer edges altered. This example is one of the three “1/2 Length Picture frames in Burnish Gold” listed in the bill illustrated in fig. 12.

Charles Willson Peale, The John Cadwalader Family, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1771. Oil on canvas. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; purchased for the Cadwalader Collection with funds contributed by the Mabel Pew Myrin Trust and the gift of an anonymous donor, 1983.) The frame is attributed to the shop of James Reynolds and measures approximately 60" x 50". All four sides have had their outer edges altered.

Molding sections, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1765–1775. White pine. (Courtesy, Powell House; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The moldings at the upper left and center are cornice sections. The molding at the upper right appears to be the lower element of a chair rail. The molding at the bottom center may be a picture slip or a section of an architrave surround.

Card table attributed to Thomas Affleck with carving attributed to the shop of James Reynolds, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1771. Mahogany with yellow pine, white oak, and tulip poplar. H. 28", W. 39 1/2", D. 19 1/4". (Courtesy, Dietrich American Foundation; photo, Will Brown.) Either this table or its mate is depicted in Charles Willson Peale’s portrait The John Cadwalader Family illustrated in fig. 24.

Details showing the cabachon and acanthus on the pier glass illustrated in fig. 13.

Details showing the cabachon and acanthus on the front rail of the card table illustrated in fig. 26.

Details showing the acanthus in the upper left corner of the pier glass illustrated in fig. 13.

Details showing the acanthus on the front rail of the card table illustrated in fig. 26.

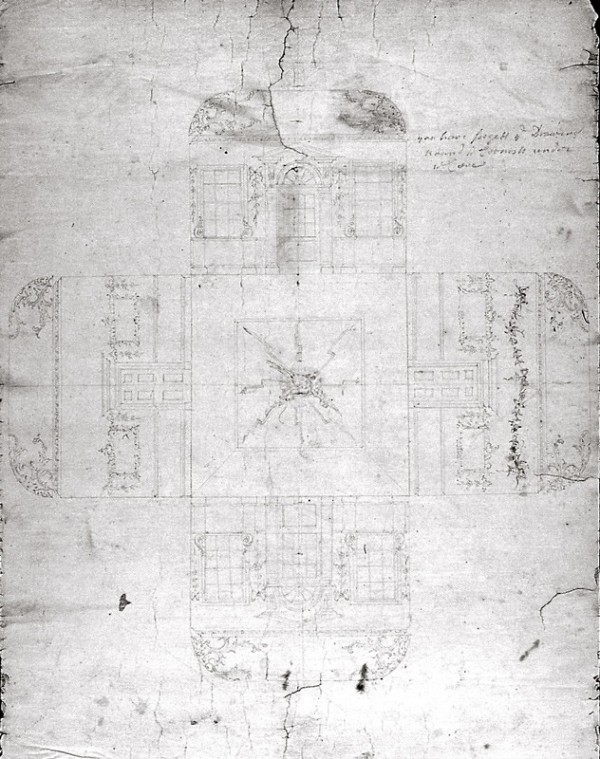

A Draft of Ornaments for the Hall at Whitehall, Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1765. Pencil on paper. Dimensions not recorded. (Photo, Luke Beckerdite.)

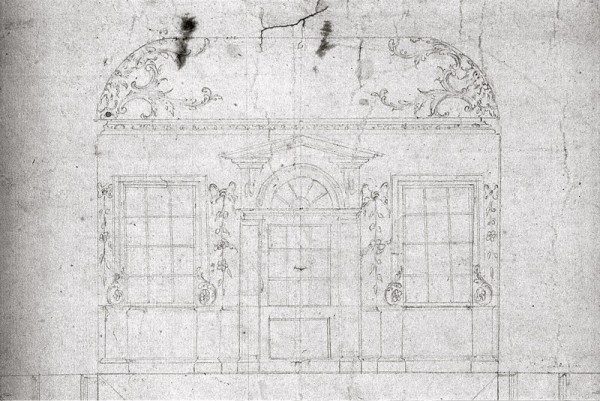

A Draft of Ornaments for the Hall at Whitehall, Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1765. Pencil on paper. Dimensions not recorded. (Photo, Luke Beckerdite.)

Detail of a mask representing one of the four winds in the great hall of Whitehall, Anne Arundel County, Maryland, 1765–1770. White pine. Dimensions not recorded. (Photo, Luke Beckerdite.)

Detail of a garland in the hall of Whitehall, Anne Arundel County, Maryland, 1765–1770. White pine. Dimensions not recorded. (Photo, Luke Beckerdite.)