Chest, Catawba County, North Carolina, 1800–1820. Yellow pine. H. 14", W. 24 1/4", D. 12". (Private collection; photo, Wesley Stewart.) This small chest was made in the Catawba Valley region of the piedmont. The façade is decorated with seven compass roses and an inscription in script. Only the first name of the owner—“Sarah”—is legible. The lid has ovolo-molded edges and wooden pintle hinges that are nailed to the back and sides of the top. The wedged dovetails and use of a center foot suggest that the maker was of Germanic descent.

Chest, Davidson County, North Carolina, 1800–1820. Yellow pine. H. 22 1/2", W. 51 3/4", D. 19 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The wedged dovetails and pinned feet and moldings suggest that the maker of this chest was trained in the Germanic tradition. The decorator probably used a rag to dab on the salmon paint and then brushed in the black background of the compass roses. No other chests with a similarly shaped central drop and foot are known.

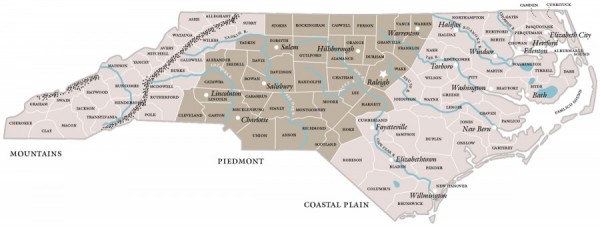

Map illustrating the eastern and western boundaries of the North Carolina piedmont, modern North Carolina counties, and major towns about 1800. (Artwork, Wynne Patterson.)

Map illustrating the major routes taken by early North Carolina settlers into the piedmont region and the major rivers along which they settled. (Adapted from a map in Catherine W. Bishir and Michael T. Southern, A Guide to the Historic Architecture of Piedmont North Carolina [Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003], p. 11; artwork, Wynne Patterson.)

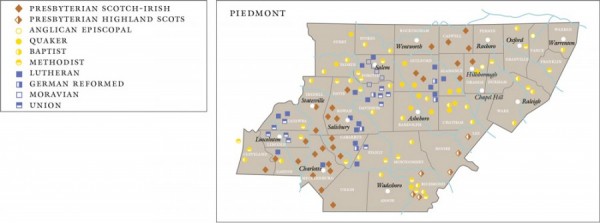

Map illustrating the ethnic settlement patterns in piedmont North Carolina as indicated by religious congregations about 1800. (Adapted from a map in Catherine W. Bishir and Michael T. Southern, A Guide to the Historic Architecture of Piedmont North Carolina [Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003], p. 12.)

John and Rachel Allen House, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1782. (Courtesy, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources.) The Allen House is representative of a typical log dwelling inhabited by early settlers in piedmont North Carolina. Until 1967 the house stood on its original site near Snow Camp but now is part of the Alamance Battleground State Historic Site.

Chest, Rowan County, North Carolina, possibly 1768. Tulip poplar with oak. H. 23", W. 50 1/2", D. 23". (Courtesy, North Carolina Museum of History; photo, Eric Blevins.)

Detail of fingerpainted tulips on the chest illustrated in fig. 7. (Photo, Eric Blevins.)

Detail of crab lock on the chest illustrated in fig. 7. (Photo, Eric Blevins.)

Latta Plantation, Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, early nineteenth century. (Courtesy, Historic Latta Plantation, Huntersville, North Carolina.) Latta Plantation exemplifies the type of frame house a member of North Carolina’s emerging backcountry elite might have occupied. The home was built by James Latta, who came from Ireland in 1785 and married Jane Knox. They were part of the strong Presbyterian community in Mecklenburg County. Today Latta Plantation is a living history farm located within Latta Plantation Nature Preserve.

Chest, probably Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1820. Yellow pine. H. 26 1/4", W. 49 1/4", D. 20 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The chest has three lower drawers (the central one was never fitted with a brass pull) separated by panels with molded surrounds. The corners of each drawer front are decorated with quarter fans like those at the corners of the case above. The front edges of the case, the recessed panels separating the three lower drawers, and most of the moldings are painted in colors that contrast with the ochre background. Marks on the surface of the chest indicate that the decorator used a compass, templates, and straightedge to lay out his work.

Detail of the central panel on the chest illustrated in fig. 11. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the right panel on the chest illustrated in fig. 11. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, probably Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1820. Yellow pine. H. 26 3/4", W. 49 3/4", D. 21 1/4". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Unlike the chest illustrated in fig. 11, this example has two drawers separated by painted lines that simulate inlaid fluting, another possible concession to neoclassical taste

Sugar pot, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1780–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 7 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

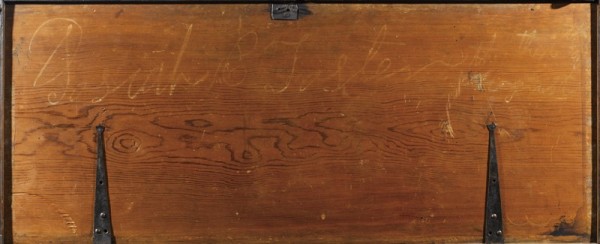

Signature of Josiah C. Foster on the underside of the lid on the chest illustrated in fig. 14. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest attributed to Daniel Anthony or Henry Anthony, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1850. Walnut with tulip poplar. H. 26 1/2", W. 49 3/8", D. 20 1/2". (Courtesy, North Carolina Museum of History; photo, Eric Blevins.)

Composite detail showing the drawer dovetails on the chests illustrated in figs. 11 (left) and 17 (right). (Photos, Gavin Ashworth [left] and Eric Blevins [right].)

Details of the left front feet of the chests illustrated in figs. 14 (left) and 17 (right). (Photos, Gavin Ashworth [left] and Eric Blevins [right]).

Chest, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Tulip poplar with yellow pine. H. 23 1/2", W. 43 1/2", D. 19 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) As on the chests illustrated in figs. 11 and 14, the polychrome areas of decoration are painted on a light ochre background. The base and lid moldings on this chest are painted reddish orange to contrast with the case. The lid is attached to the case with forged iron strap hinges. The case and the feet are joined with wedged dovetails, and the lid, base moldings, and feet are attached with both wooden pins and nails. The maker produced a walnut chest identical to this example, which also has a recovery history in the Kimesville area.

Detail of the left panel on the chest illustrated in fig. 20. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, Stanly County, North Carolina, 1820–1840. Yellow pine. H. 25 3/4", W. 47 1/4", D. 20". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The decorator used a round brush or wadded cloth to produce overlapping circular patterns in the salmon and blue grounds. After laying out his designs with a straightedge and compass, the decorator used the same ornamental technique to apply the white paint.

Detail of the central fylfot on the lid of the chest illustrated in fig. 22. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The decorator used a brush to apply the thin black line accentuating the lobes of the fylfots.

Chest, Cabarrus County, North Carolina, 1808–1840. Tulip poplar with yellow pine. H. 25", W. 49 5/8", D. 22 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The inner foot profile is a single cove and ovolo.

Chest, Stanly County, North Carolina, 1823–1840. Yellow pine. H. 30 1/2", W. 50 1/2", D. 24". (Collection of Elbert H. Parsons Jr.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a side of the chest illustrated in fig. 22. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet on this chest terminate with an ovolo at the top.

Detail of a side of the chest illustrated in fig. 25. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet on this chest terminate with an additional cove at the top, making them taller and broader than those illustrated in fig. 26.

Detail showing coped moldings on the chest illustrated in fig. 25. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Cupboard attributed to the Jacob Sanders shop, Montgomery County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Yellow pine. H. 84 1/4", W. 50 1/4", D. 21 3/8". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) A front baseboard that descends to a pronounced peak is common on pieces from this group. Approximately twenty examples are known.

Detail showing the case dovetails, heavy beading, and applied ogee moldings on the cupboard illustrated in fig. 29. (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing a mitered and nailed foot joint and a strap-and-pintle hinge on the cupboard illustrated in fig. 29. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The pintle hinges allow the doors to be easily removed.

Detail of the stacked cornice and fascia on the cupboard illustrated in fig. 29. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The lunettes were laid out with a compass and then sawed.

Chest attributed to the Jacob Sanders shop, Montgomery County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Yellow pine. H. 37 1/2", W. 37 1/2", D. 21 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Fylfots and compass roses like those on this chest are the most common motifs on piedmont North Carolina furniture.

Detail of a strap-and-pintle hinge on the chest illustrated in fig. 33. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

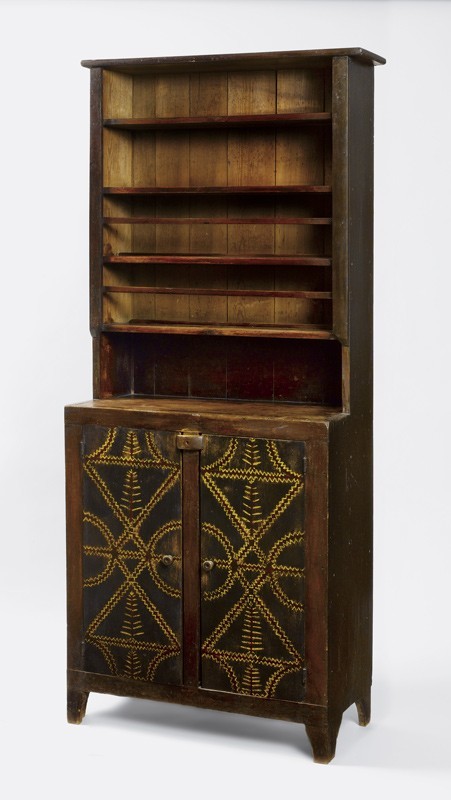

Dish dresser attributed to the Jacob Sanders shop, Montgomery County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Yellow pine. H. 85", W. 50", D. 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Craig McDougal.) This object has incurved feet like those on the dish dresser and chest illustrated in figs. 38 and 43. Like this example, most dish dressers in the group have central stiles, although not all are shaped.

Detail of the cornice decoration on the dish dresser illustrated in fig. 35.

Hanging cupboard attributed to the Jacob Sanders shop, Montgomery County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Yellow pine. H. 27 1/4", W. 18 1/2", D. 9 1/2". (Courtesy, Greensboro Historical Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Early photograph of a dish dresser with scalloped stiles similar to those on the hanging cupboard illustrated in fig. 37. (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) The crescent-shaped scallops terminate at a shelf or plate rail and are connected by a vertical rod. The stiles on this dresser were removed and discarded during the twentieth century.

Hanging cupboard attributed to the Jacob Sanders shop, Montgomery County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Yellow pine. H. 29 3/4", W. 25 1/2", D. 13". (Wilkinson Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a strap-and-pintle hinge on the door of the hanging cupboard illustrated in fig. 39. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest of drawers attributed to the Jacob Sanders shop, Montgomery County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Walnut and light wood with yellow pine. H. 52 3/4", W. 39", D. 19 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the lightwood cock-beading, lunetted fascia, and crescent inlay on the chest of drawers illustrated in fig. 41. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest attributed to the Jacob Sanders shop, Montgomery County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Yellow pine. H. 17 1/4", W. 31 1/4", D. 13 1/4". (Courtesy, Greensboro Historical Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dish dresser, Montgomery or Randolph County, North Carolina, 1820–1850. Yellow pine. H. 80 1/2", W. 61 1/2", D. 21 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This piece does not have a central stile like the four other related dressers.

Chest, Rowan County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Tulip poplar with yellow pine. H. 24", W. 49 1/4", D. 20 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Wesley Stewart.) The cream-colored paint on this chest was originally much thicker. The sides and feet are joined with wedged dovetails and the base is nailed in place. The foot is unusual in having sawtooth shaping where the bracket rises toward the base molding.

Detail of the central motif on the chest illustrated in fig. 45. (Photo, Wesley Stewart.) Although now worn, the paint used for the lobe-and-spade-shaped design may have been patterned.

Chest, Chatham County, North Carolina, 1801–1830. Yellow pine. H. 29", W. 48", D. 18". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Beneath the black ground is a red primer coat, probably applied to seal the resinous yellow pine. The chest has wedged dovetails, unusually tall bracket feet, and an applied, filleted ogee beneath its molded top.

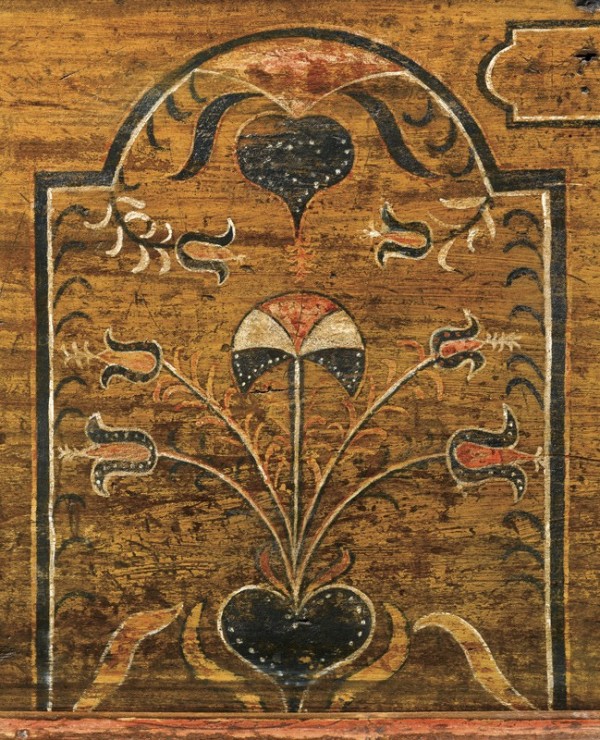

Detail of the central motif on the chest illustrated in fig. 47. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Doubloon, Ephraim Brasher, New York, 1787. Gold. (Courtesy, American Numismatic Society.)

Touchmark of Jehiel Johnson, Fayetteville, North Carolina, 1817–1819. Pewter. (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Detail of the right side of the chest illustrated in fig. 47. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The case extends about one inch beyond the rear edge of the back feet, presumably to accommodate an architectural baseboard.

Chest, Chatham or Randolph County, North Carolina, 1801–1830. Yellow pine. H. 27 3/8", W. 51 1/8", D. 22 3/8". (Courtesy, High Museum of Art.)

Chest, Chatham County, North Carolina, 1840–1850. Yellow pine. H. 24 1/2", W. 41", D. 19". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the central façade decoration on the chest illustrated in fig. 53. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Three chests in this group have the owner’s initials painted in script. The circular belly of the vase and some of the leaves originally had a light pink wash, but only faint outlines and tiny fragmented areas of color remain. The upper section of the vase retains a thicker, darker coat of pink paint like that on the flowers and buds.

Detail of a rear foot on the chest illustrated in fig. 53. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, Chatham County, North Carolina, 1840–1850. Yellow pine. H. 23 1/2", W. 43 1/2", D 18 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The case and feet of this chest are joined with wedged dovetails. The rear feet do not extend beyond the back of the case, and their supports are nailed into the bottom in a conventional manner.

Chest, possibly Rutherford County, North Carolina, 1800–1850. Yellow pine. H. 26 3/4", W. 41 1/2", D. 16". (Private collection; photo, Wesley Stewart.) The decorator of this chest probably used a sponge or rag dipped in black paint to apply the arcs and dots on the façade. This object and the chest illustrated in fig. 58 are similar in form, but their construction differs. The case of the former is dovetailed, whereas the case of the latter is joined and secured with screws.

Chest, possibly Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, 1800–1850. Yellow pine. H. 30 1/4", W. 44 1/2", D. 19 7/8". (Private collection; photo, courtesy Deanne Levison.) The front and back boards are screwed to the side boards, the frame is constructed with pinned mortise-and-tenon joints, and both the case and waist molding are nailed to the frame.

Chest, Wake County, North Carolina, 1800–1820. Yellow pine. H. 24", W. 29", D. 15". (Wilkinson Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The lid has lost much of its paint, but it appears to have been blue with red edges and moldings. The front and side boards are joined with blind dovetails, the rear and side boards are joined with half-blind dovetails, and the front and side feet are joined with fully exposed dovetails. The lid battens are attached with pinned tongue-and-groove joints, and the moldings and base are secured with cut nails.

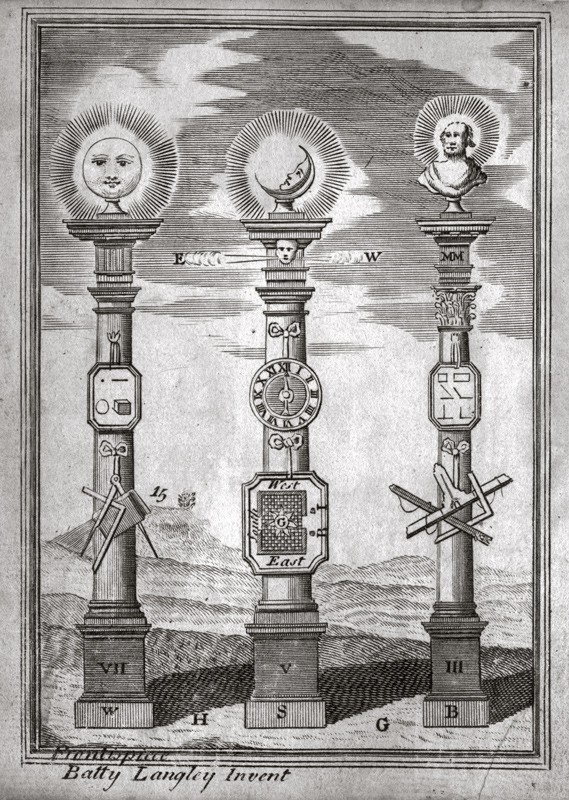

Frontispiece of B. Langley and T. Langley, The Builder’s Jewel: or the Youth’s Instructor and Workman’s Remembrancer, 12th ed. (Dublin: James Williams in Skinner-Row, 1768). (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Detail of the central motif on the façade of the chest illustrated in fig. 59. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

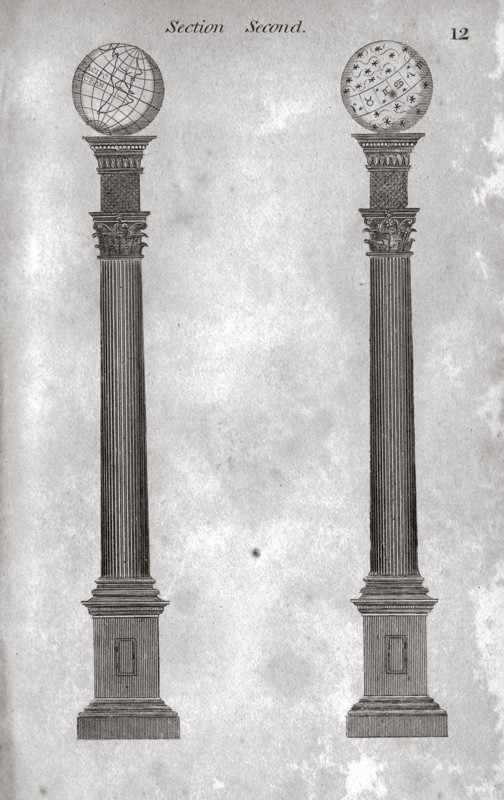

Detail of pillars topped with terrestrial and celestial globes (R. W. Jeremy L. Cross, G.L., The True Masonic Chart or Hieroglyphic Monitor, 5th ed. [New York, 1842], p. 12). (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) These pillars symbolized the Fellow Crafts Degree, Section Second.

Detail of the right bird on the façade of the chest illustrated in fig. 59. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The design of the birds on the chest is similar to that of the eagle in the lower right quadrant of the shield shown in fig. 65.

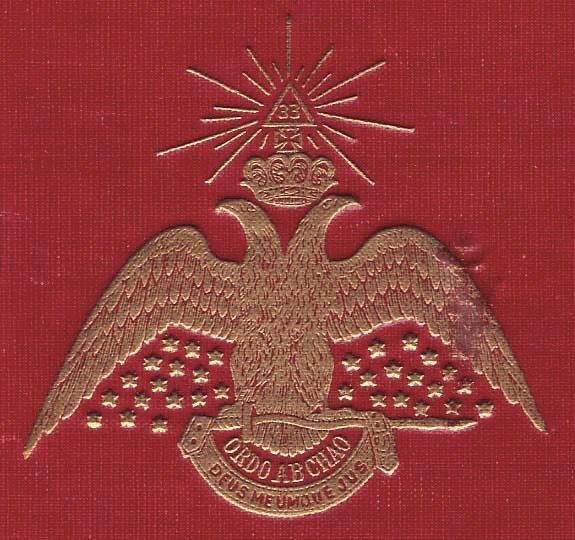

Detail of the cover of Albert Pike, Morals and Dogma of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry (1873).

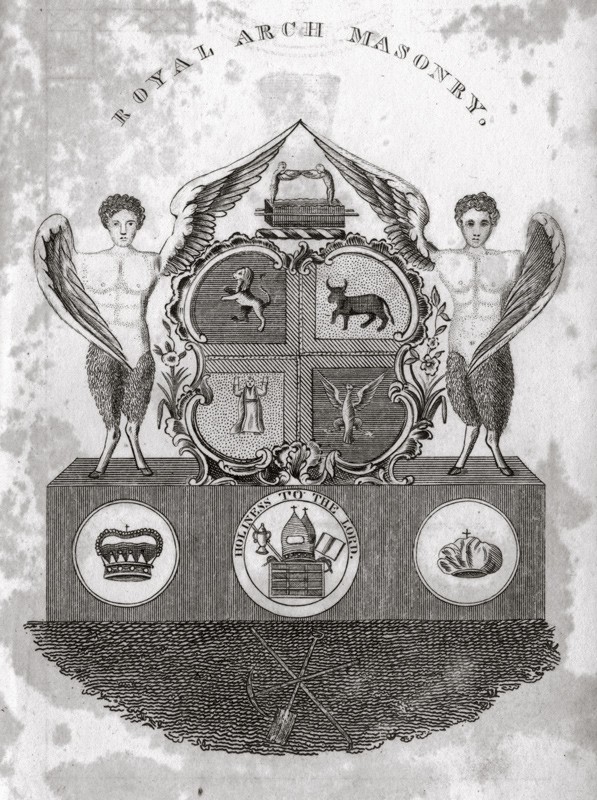

Detail of facing cherubim guarding the ark of the covenant (R. W. Jeremy L. Cross, G.L., The True Masonic Chart or Hieroglyphic Monitor, 5th ed. [New York, 1842], p. 42). (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Detail of the right building on the façade of the chest illustrated in fig. 59. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the right side of the chest illustrated in fig. 59. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

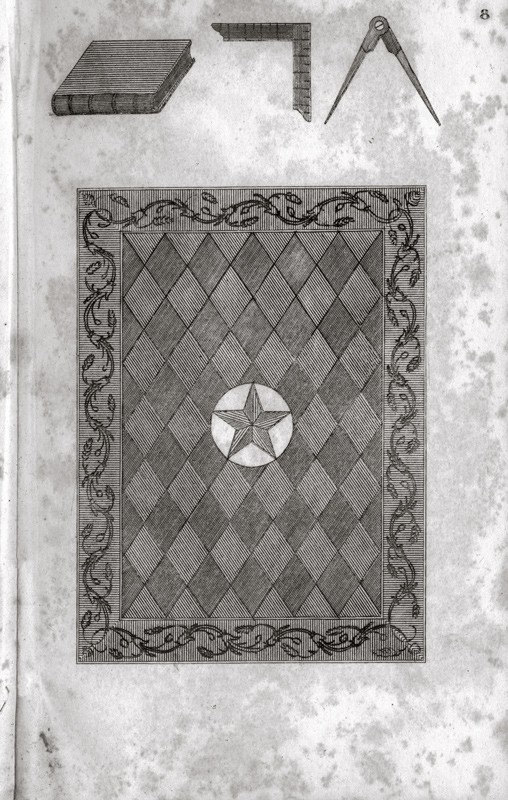

Detail of a Masonic floorcloth (R. W. Jeremy L. Cross, G.L., The True Masonic Chart or Hieroglyphic Monitor, 5th ed. [New York, 1842], p. 8). (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

John Luker, Masonic master’s chair, pillars, and candlestands, Vinton County, Ohio, 1870. (Courtesy, Scottish Rite Masonic Museum and Library, gift of the Estate of Charles V. Hagler; photo, David Bohl.) The shape of the large pillars is similar to that of the central motif on the chest illustrated in fig. 59.

Cupboard, Catawba, Lincoln, Cleveland, or Burke County, North Carolina, 1880–1920. Yellow pine. H. 52 1/2", W. 35 3/4", D. 15". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The decorator typically used one ground color for the stiles and rails and another for the doors, top, and case sides. This allowed him to frame his ornamental designs.

Cupboard, Catawba, Lincoln, Cleveland, or Burke County, North Carolina, 1880–1920. Yellow pine. H. 53", W. 36", D. 16". (Private collection; photo, Wesley Stewart.) The brown may be a stain or wash rather than an opaque paint.

Dish dresser, Catawba, Lincoln, Cleveland, or Burke County, North Carolina, 1880–1920. Yellow pine. H. 76", W. 34", D. 15". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The thick application of bright paint makes the more methodical decorator’s work particularly dramatic.

Composite detail showing the door decoration on (from left to right) a dish dresser (fig. 72) and two cupboards (figs. 70, 71). (Photo, Gavin Ashworth [left and middle] and Wesley Stewart [right].)

Cupboard, Catawba, Lincoln, Cleveland, or Burke County, North Carolina, 1880–1920. Yellow pine. H. 53", W. 36", D. 16 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Wesley Stewart.) The name “Zara Havner” is written in pencil on the inside surface of the left door. The only person with that name in North Carolina census records from the early twentieth century was an eight-year-old girl who lived in Icard Township in Burke County in 1900. She was the daughter of farmer Daniel A. Havner and his wife, Margaret.

Cupboard, Catawba, Lincoln, Cleveland, or Burke County, North Carolina, 1880–1920. Yellow pine. H. 52", W. 36", D. 16". (Private collection; photo, Wesley Stewart.) On this cupboard and the example illustrated in fig. 76, the decorator used lunettes to outline the diamonds and the designs beneath them. The methodical painter of the related cupboards and dish dresser used sawtooth lines in the same context. This cupboard is the only example with quatrefoil motifs, which may have been intended to represent flowers.

Cupboard, Catawba, Lincoln, Cleveland, or Burke County, North Carolina, 1880–1920. Yellow pine. H. 53", W. 36", D. 15 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Wesley Stewart.)

Composite detail showing the door decoration on cupboards illustrated in (from left to right) figs. 74, 75, and 76. (Photos, Wesley Stewart.)

Basket, Qualla Boundary, North Carolina, ca. 1950. River cane. H. 11", W. 9", D. 8 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Wesley Stewart.)

Basket, Qualla Boundary, North Carolina, ca. 1950. River cane. H. 16", W. 17 1/2", D. 8". (Private collection; photo, Wesley Stewart.)

Washstand, Iredell County, North Carolina, ca. 1850–1875. Yellow pine. H. 30 1/2", W. 31", D. 17". (Private collection; photo, Wesley Stewart.)

Detail of the compass rose on top of the washstand illustrated in fig. 80. (Photo, Wesley Stewart.)