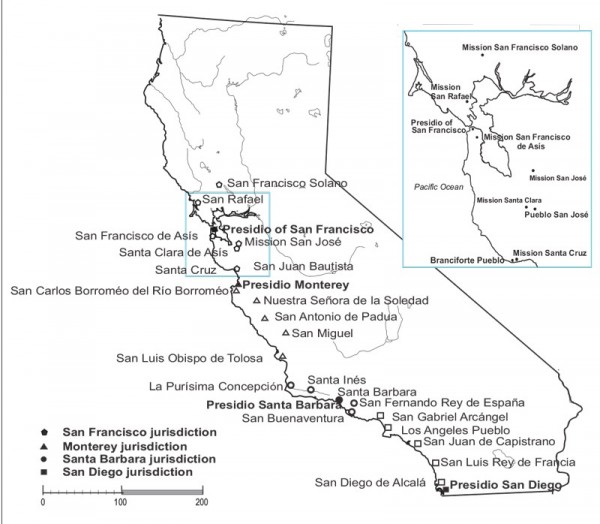

Map of Alta California showing presidio districts and associated missions, pueblos, and presidios during the Spanish and Mexican era, 1769–1848. (Ronald L. Bishop, Smithsonian Institution.)

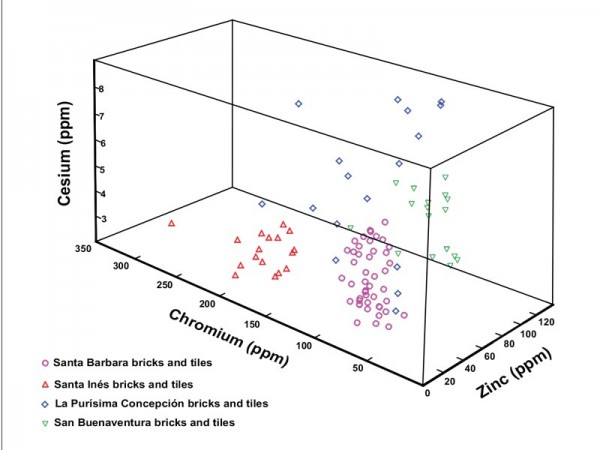

Plot of the data obtained for the architectural ceramics from Santa Barbara Presidio and Missions Santa Barbara, Santa Inés, La Purísima Concepción, and San Buenaventura. The sample locations are shown relative to their abundance of cesium, chromium, and zinc. (M. James Blackman, Smithsonian Institution.)

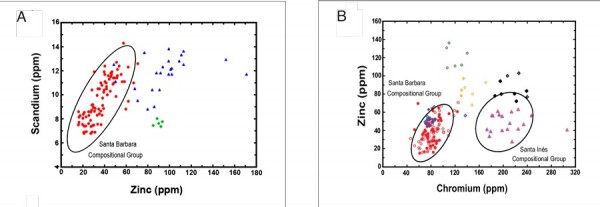

(A) Plot of the bricks, tiles, and plain ceramic ware from the Santa Barbara Presidio, Missions Santa Barbara and San Buenaventura, and the Olivas Adobe relative to the abundances of scandium and zinc. The two statistically refined groups enclosed with 95% confidence ellipses are composed of the samples from Santa Barbara and San Buenaventura chemical group 1. The green down-pointing triangles represent Mission San Buenaventura bricks and tiles of chemical group 2. (B) Plot of the bricks, tiles, and plain ceramic ware from the Santa Barbara Presidio, Missions Santa Barbara and San Buenaventura, and Olivas Adobe relative to the abundances of chromium and zinc showing all of the San Buenaventura ceramics from the Santa Barbara chemical group. (M. James Blackman, Smithsonian Institution.)

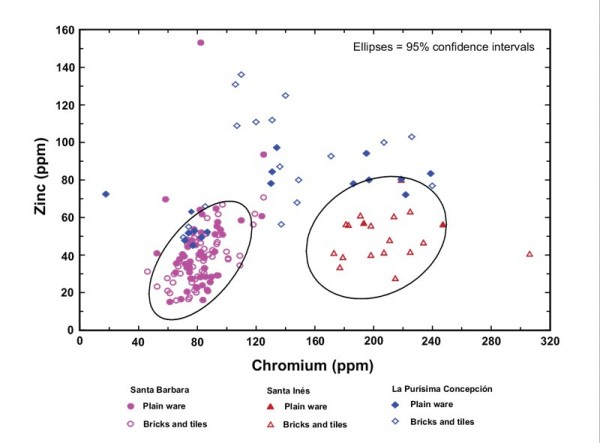

Plot of bricks, tiles, and plain earthenware ceramics relative to the abundance of chromium and zinc. The two statistically refined groups are enclosed with 95% confidence ellipses. Resolution of the overlap between ceramics from Mission Santa Barbara and La Purísima Concepción is illustrated in fig. 5. (M. James Blackman, Smithsonian Institution.)

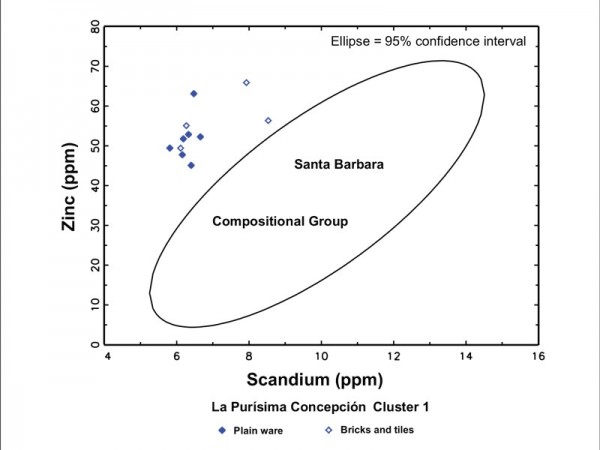

Plot of La Purísima Concepción cluster 1 plain earthenware and architectural ceramics shown relative to concentrations of scandium and zinc. All of the La Purísima Concepción ceramics are shown to lie outside of the 95% confidence interval for the Santa Barbara compositional group. (M. James Blackman, Smithsonian Institution.)

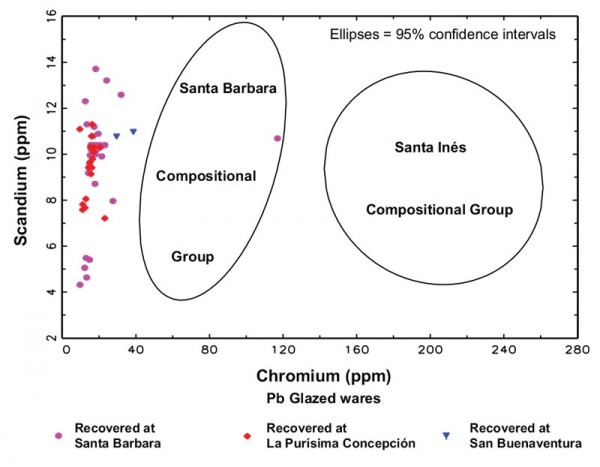

Plot of the concentrations of chromium vs. scandium for all the lead-glazed earthenwares recovered from sites in the Santa Barbara jurisdiction relative to the 95% confidence ellipses for the Santa Barbara and Santa Inés architectural and plain earthenware ceramics compositional groups. (M. James Blackman, Smithsonian Institution.)

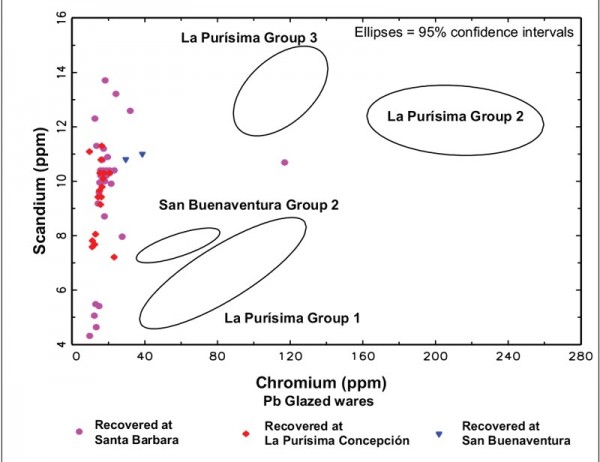

Plot of the concentrations of chromium vs. scandium for all the lead-glazed earthenwares recovered from sites in the Santa Barbara jurisdiction relative to the 95% confidence ellipses for the San Buenaventura and La Purísima Concepción architectural and plain earthenware ceramics compositional groups. (M. James Blackman, Smithsonian Institution.)

Fragments of bricks and tiles recovered from archaeological excavations at El Presidio de Santa Barbara (CA-SBA-133), Santa Barbara, California, 2005. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

Civilian Conservation Corps members making roof tiles at La Purísima Concepción, near Lompoc, California, ca. 1938. (Courtesy, La Purísima Mission State Historic Park Archives.)

The arc of a curved roof tile replicated by students at El Presidio de Santa Barbara State Historic Park, 2007. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

Unfired roof tiles drying on curved plaster molds cast from original Presidio roof tiles, 2007. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

(Left) Roof tile made with somewhat dry clay; (right) roof tile formed with somewhat wet soft clay, which is relatively flat or collapsed, 2007. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

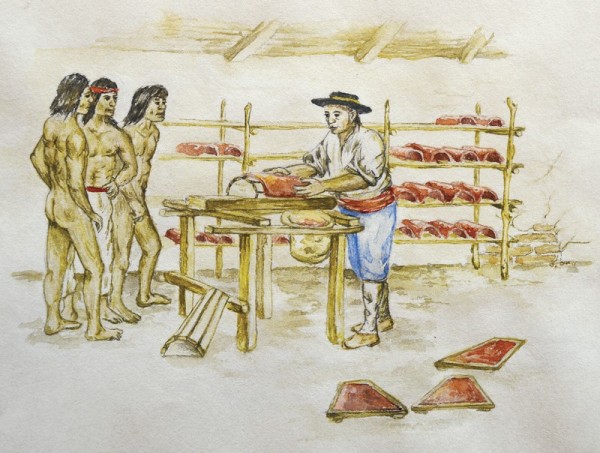

The Chumash Indians learned tile making at La Purísima Concepción and other missions in the region. Oil painting, artist and date unknown. (Courtesy, Santa Barbara Presidio Research Center.)

Clamp-style brick kiln at Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.) Note the multiple stoking holes.

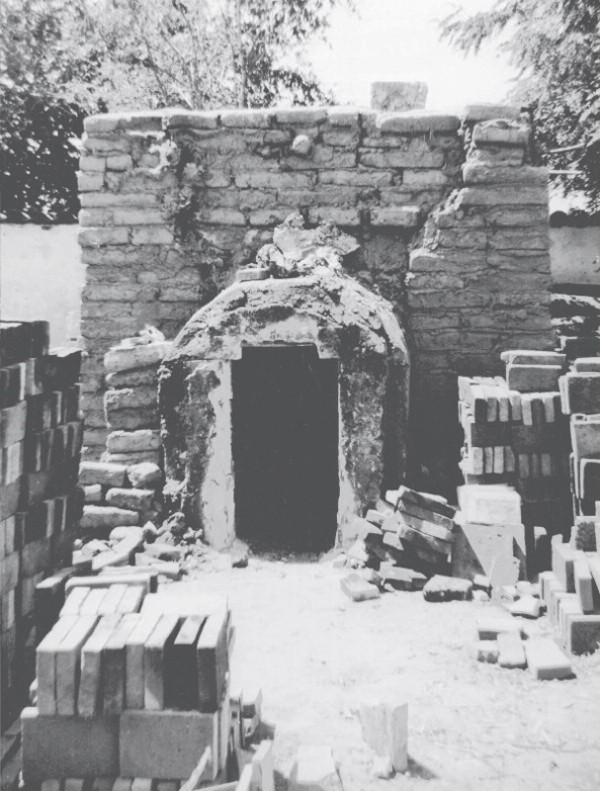

Brick and tile kiln, Mexico, ca. 1950s. (Courtesy, Santa Barbara Mission Archive Library, Edith Webb Collection; photo, Arthur Woodward.)

Located in Tecate, Mexico, this brick-and-tile kiln owned by George Davidson fired the roof and floor tiles for the 1985 reconstruction of the Santa Barbara Presidio Chapel. (Photo, Michael Pownall.)

Two-chamber updraft brick kiln used by Franciscan friars during the 1942 restoration of Mission San Miguel in California. (Courtesy, Santa Barbara Mission Archive Library, Edith Webb Collection.)

Bricks and tiles produced by the Redwind Native American Community in San Luis Obispo, California, 1980. (Courtesy, Santa Barbara Presidio Research Center; photo, Norman Caldwell.)

Updraft brick-and-tile kiln used by the Redwind Native American Community, 1980. (Courtesy, Santa Barbara Presidio Research Center; photo, Norman Caldwell.)

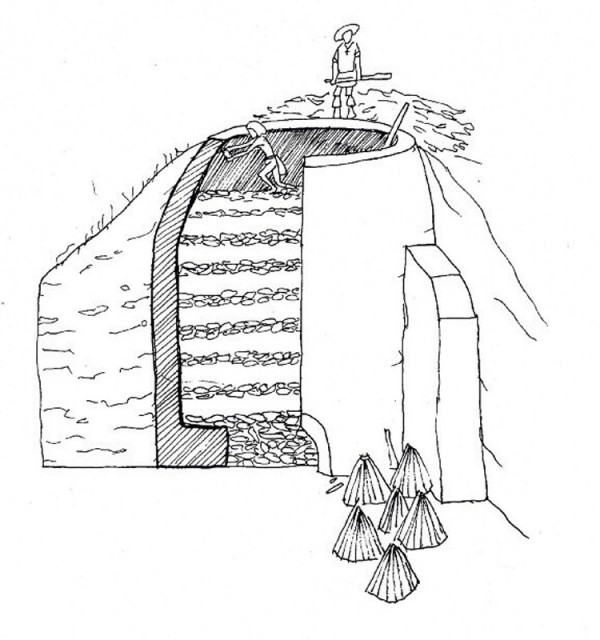

“Volcano-style” kiln at Mission San Juan Capistrano. (Drawing by Jack S. Williams; illustrated in “Field Notes: Kiln Documentation, Mission San Juan Capistrano [CA-ORA-856H],” 1996.)

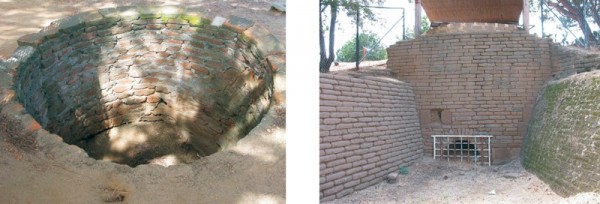

(Left) Small, open-top circular tile kiln at Mission San Luis Rey de Francia; (right) large, open-top circular tile kiln at Mission San Luis Rey de Francia, 2009. (Photos, Michael Imwalle.)

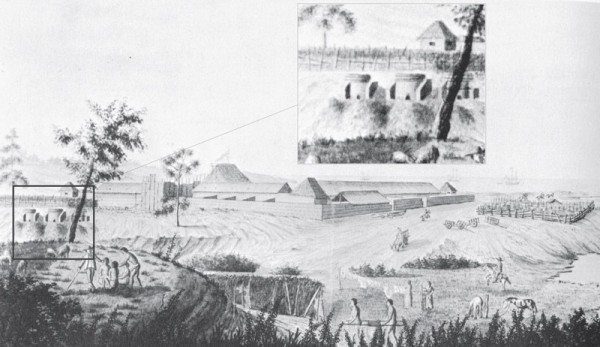

Sketch by José Cardero of the Monterey Presidio, with inset showing tile kiln details, 1791. (Courtesy, Bancroft Library.)

Circular, open-top tile kilns used during the 1920s restoration of the San Bernadino Asistencía of Mission San Gabriel. (Courtesy, Santa Barbara Mission Archive Library, Edith Webb Collection.)

Archaeologist M. R. Harrington alongside La Purísima Concepción tile kiln, 1940. (Courtesy, La Purísima Mission State Historic Park Archives.)

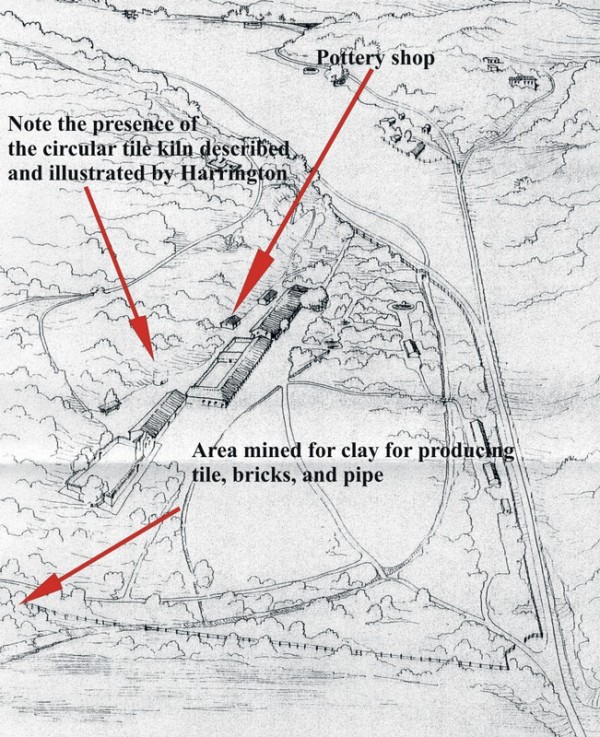

Map of La Purísima Concepción complex with ruins of circular tile kiln, 1938. (Courtesy, La Purísima Mission State Historic Park Archives.)

Reconstructed arch of feature interpreted as a tile kiln by M. R. Harrington at La Purísima Mission State Historic Park, 2007. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

Large tallow vat added to top of feature formerly interpreted as a tile kiln by M. R. Harrington, 2007. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

Scale model (1/10th) of Mission San Antonio tile kiln based on Julia Costello’s 1997 plan. (Photo, Ruben Reyes.)

Scale model (1/10th) of Mission San Antonio tile kiln with one of the added slanted or “cockeyed” entryways removed. (Photo, Ruben Reyes.)

Close-up of Mission San Antonio kiln model showing position of fired tile arches that would form the firing chamber of a two-chamber updraft kiln. (Photo, Ruben Reyes.)

Top of arches forming the open floor or grate of the ware chamber, La Purísima Mission State Historic Park, 2007. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

Interior arches of a two-chamber updraft kiln, La Purísima Mission State Historic Park, 2007. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

Firing of 1/10th-scale model of the tile kiln at Mission San Antonio, 2007. (Photo, Ruben Reyes.) This demonstration helped to better understand how the structure was modified from its original use.

Kelly Greenwalt learned the fundamentals of making pottery in about forty hours under the watchful eye of master potter Ruben Reyes, 2006. (Photo, Russell K. Skowronek.)

A bucket of unprocessed clay from Mission Creek near Mission San José close to the eastern shores of San Francisco Bay, 2006. (Photo, Ruben Reyes.)

Reconstructed pottery shop at Mission La Purísima Concepción, 2007. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.) Large amounts of clay would have been pulverized in this mixing vat. Historically a burro would have provided the power for reducing the clay to a satisfactory consistency.

Mixed clay from Mission San José ready for aging and drying, 2006. (Photo, Ruben Reyes.)

Block of clay from Mission San José ready for wedging, 2006. (Photo, Ruben Reyes.)

Wedging, a very labor- and time-intensive endeavor, is necessary for removing air bubbles prior to pottery making, 2006. (Photo, Kelly Greenwalt.)

A ball of processed clay from Mission San José ready to be used, 2006. (Photo, Ruben Reyes.)

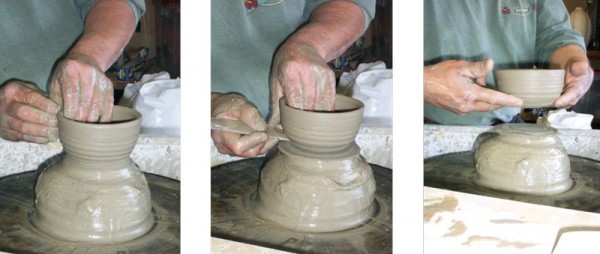

Throwing from the mound was one of the techniques used in Spanish California. (Left) a small bowl or cup is being “pulled” from the mound; (center) the nearly finished cup is cut from the mound; (right) the finished vessel is lifted from the mound, leaving the remainder of the clay for the next vessel, 2006. (Photos, Kelly Greenwalt.)

Base of a ceramic vessel found at Mission San Antonio de Padua, near Jolon, California, bearing the distinctive marks associated with vessels thrown from the mound, 2006. (Photo, Ruben Reyes.)

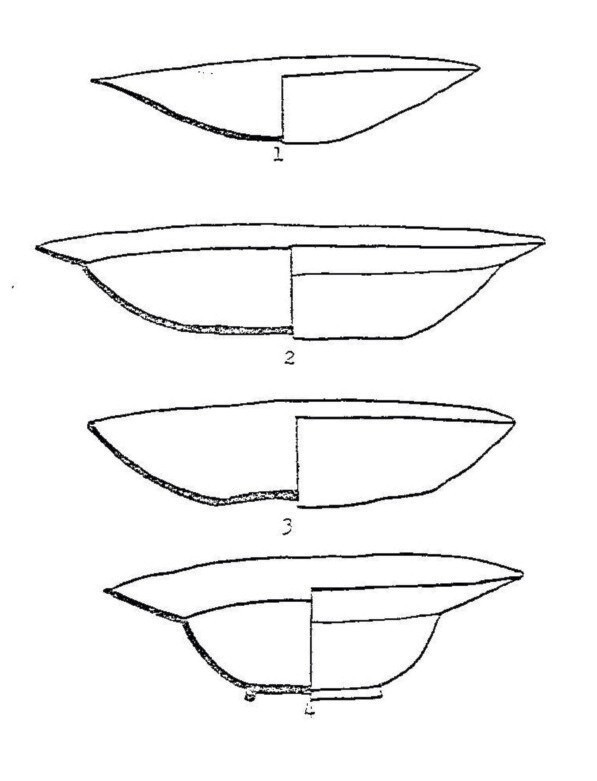

Jack Williams was able to reconstruct several forms of plates and brimmed bowls in his analysis of ceramics from Mission San Antonio de Padua. (Drawing by Elizabeth Skowronek, based on original in Williams, “Early Nineteenth Century Plainware Pottery from Mission San Antonio de Padua Alta California” [1983], ms. on file at Mission San Antonio Archives, Jolon, California.)

Replicated 10 1/2" wheel-thrown brimmed bowl based on forms from Mission San Antonio de Padua, 2015. (Photo, Ruben Reyes.)

This nearly intact 4" diameter wheel-thrown small bowl or cup was excavated at Mission San Antonio de Padua, 2006. (Photo, Ruben Reyes.)

Replicated 4" diameter wheel-thrown small bowl or cup based on the original found at Mission San Antonio de Padua, 2006. (Photo, Ruben Reyes.)

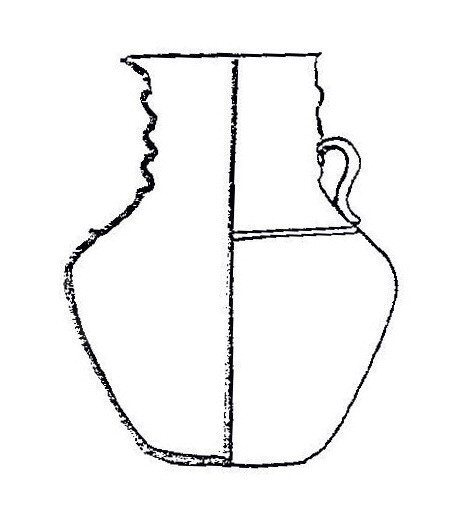

Jack Williams was able to reconstruct a chocolotera (chocolate pot) based on sherds found at Mission San Antonio de Padua. (Drawing by Elizabeth Skowronek, based on original in Williams, “Early Nineteenth Century Plainware Pottery from Mission San Antonio de Padua.”)

Replicated 9" wheel-thrown chocolotera with pulled handle, based on Jack Williams’s 1983 reconstruction at Mission San Antonio de Padua, 2015. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

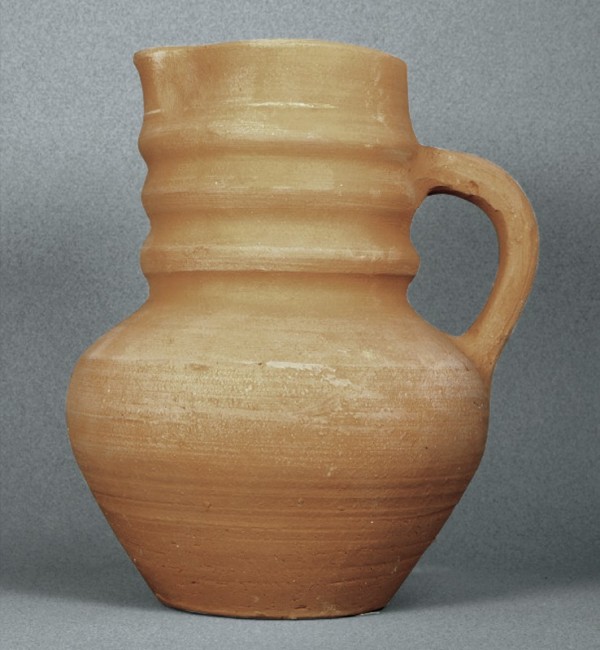

Found at Mission San Antonio de Padua, this 10" wheel-thrown storage or cooking vessel may have been modeled after basketry forms. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

Replicated wheel-thrown storage or cooking vessel based on one found at Mission San Antonio de Padua, 2015. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

This shallow, 7" diameter bowl or plate was found at Mission Santa Clara de Asís. (Photo, Ruben Reyes.) It was made using the anvil technique.

Ceramic anvils made by Ruben Reyes, 2006. (Photo, Ruben Reyes.)

A slab of clay is placed on the anvil, then paddled over the anvil, 2006. (Photo, Kelly Greenwalt.)

The anvil is carefully removed from the now-formed clay bowl, 2006. (Photo, Kelly Greenwalt.)

The clay bowl awaiting a final trimming of excess clay, 2006. (Photo, Kelly Greenwalt.)

College students from Santa Clara University in 2007 were making vessels in less than thirty minutes using the anvil technique. (Photo, Ruben Reyes.)

Experiments with open-pit fires demonstrated the utility of this production process, 2007. (Photo, Ruben Reyes.)

Close-up of “firing clouds” produced on vessels during experimental pit firing, 2007. (Photo, Ruben Reyes.)

Ruben Reyes adjusting flue to regulate heat of demonstration kiln during experimental firing at El Presidio de Santa Barbara State Historic Park, 2006. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

Saggers produced by Ruben Reyes for experimental glaze firing, 2006. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

Example of both clavos and clay rods supporting mayólica vessels in a cutaway view of a sagger, 2006. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

Replica San Elizario Polychrome mayólica vessel supported by fired clay rods used to support maiolica vessels. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

Example of Spanish colonial caballitos found at Mission Nuestra Señora del Espíritu Santo de Zúñiga in Goliad, Texas, 2008. (Photo, Russell Skowronek.)

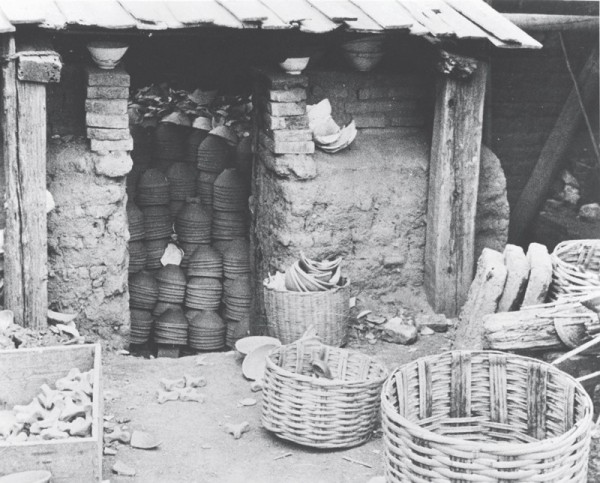

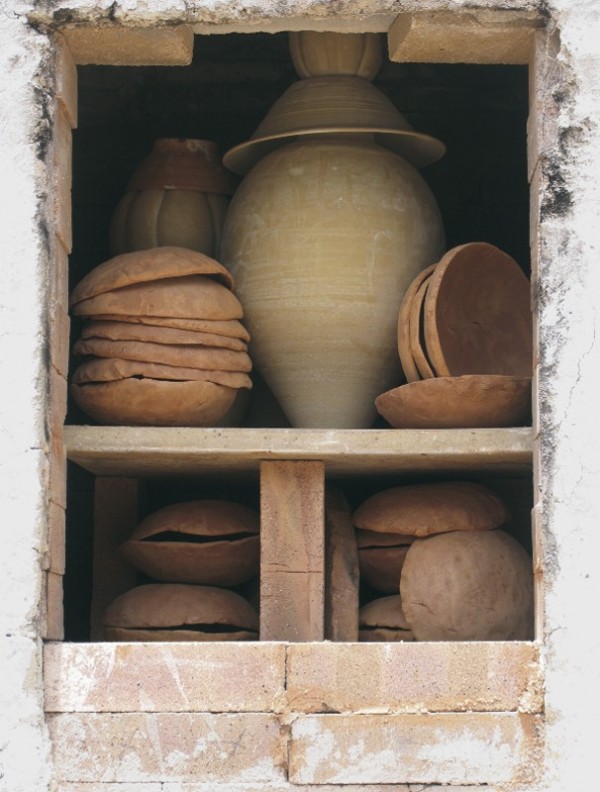

Mexican kiln loaded with vessels for a bisque firing, ca. 1950s. (Courtesy, Santa Barbara Mission Archive Library, Edith Webb Collection; photo, Arthur Woodward.) Note caballitos in left foreground.

Replicated San Agustín Blue-on-white mayólica replica with caballito in place after firing, 2007. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

Visible in this close-up are the scars left in the surface of the glaze of this replicated San Elizario Polychrome mayólica vessel, a result of breaking the caballito free of the vessel, 2007. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

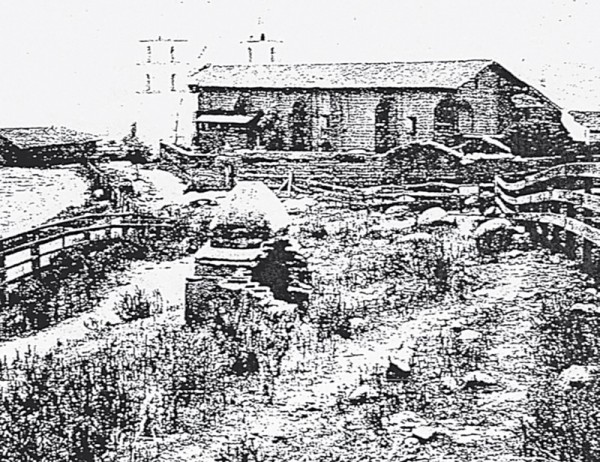

Santa Barbara Mission with pottery kiln in foreground, 1880s. (Courtesy, Santa Barbara Mission Archive Library, Edith Webb Collection.)

Detail of the photograph illustrated in fig. 67.

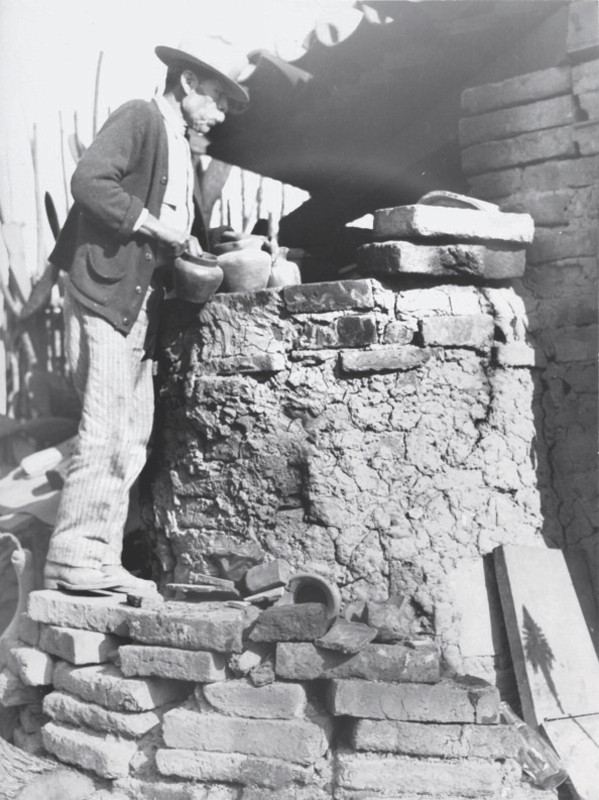

Potter Ireneo Mendoza with top-loading, updraft pottery kiln at Mission San Juan Capistrano, 1937. (Courtesy, Santa Barbara Mission Archive Library, Edith Webb Collection; photo, Hugh Pascal Webb.)

Overview of pottery production and firing demonstration at El Presidio de Santa Barbara State Historic Park, Santa Barbara, California, 2006. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

Pottery shop and potter’s wheel at La Purísima Mission State Historic Park, 2006. (Photo, Ruben Reyes.)

Replica pottery kiln at La Purísima Mission State Historic Park, 2006. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

Ruben Reyes constructing arches, frame, and walls of a two-chamber updraft demonstration kiln at El Presidio de Santa Barbara State Historic Park, 2006. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

Ruben Reyes stoking during experimental kiln firing at El Presidio de Santa Barbara State Historic Park, 2007. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

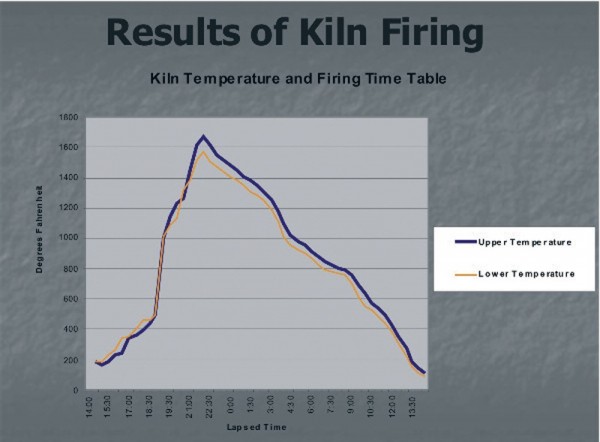

Graph showing the progression of kiln temperatures during experimental kiln firing in 2007.

Presidio demonstration kiln with bisqued vessels after initial experimental firing in April 2006. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

Ruben Reyes adjusting the flue on California’s only wood-fired, Spanish colonial–style updraft kiln, El Presidio de Santa Barbara, June 2006. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

Anacapa School students Joshua Figueroa, Aubrey Cazabat, and Wishiah Roper screening clay for ceramic production, 2007. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

Ruben Reyes demonstrating wheel-thrown pottery for schoolchildren at El Presidio de Santa Barbara State Historic Park’s “Early California Days” living-history program, 2007. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

A group of green and bisque-fired ceramics ready for experimental firing at El Presidio de Santa Barbara State Historic Park, 2007. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

San Diego Polychrome mayólica plate fragment, Puebla, Mexico, 1750–1835. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.) The tin-glazed ceramics of the Spanish colonial world are very colorful. This fragment with a sunflower design was recovered from archaeological investigations at El Presidio de Santa Barbara in 2009.

San Elizario Polychrome mayólica plate fragment, Puebla, Mexico, 1750–1830. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.) This was recovered at El Presidio de Santa Barbara.

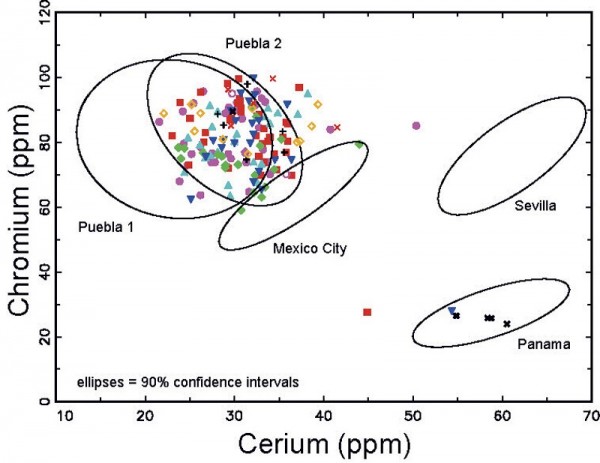

Plot of cerium vs. chromium showing the association of the California mayólica samples with the major Mexican production centers at Puebla and Mexico City, the Spanish center at Sevilla/Triana, and the Panama City production in Panama. The ellipses represent 90% confidence intervals. Each symbol represents a different mission, presidio, or pueblo (individual sites not identified). (M. James Blackman, Smithsonian Institution.)

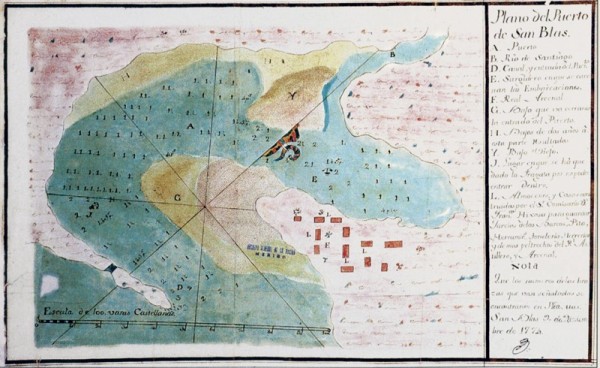

Eighteenth-century plan of the port and naval supply depot at San Blas, Mexico. (Courtesy, Archivo General de Nación, Mexico City, Mexico.)

Mayólica reproductions from Mexico. (Left) Puebla tradition, twentieth century; (right) Aranama tradition. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

Partially reconstructed Aranama Polychrome, 1750–1800, and Puebla Blue-on-white, 1750–1850, Puebla, Mexico. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.) These fragments are from archaeological excavations at Soledad Mission.

The dining room (comedor) of the commandant’s quarters (comandancia) at El Presidio de Santa Barbara State Historic Park in Santa Barbara, California, 2009. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

Replicated soup plate (sopero) on potter’s wheel in Pottery Shop at La Purísima Mission near Lompoc, California, 2006. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

Ruben Reyes wore a protective mask and gloves while mixing the tin glaze for the 2007 experimental glazing and painting project conducted at El Presidio de Santa Barbara State Historic Park in Santa Barbara, California. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

Iron-oxide concretions excavated on the grounds of El Presidio de Santa Barbara State Historic Park were manually ground into fine powder for use as a black or brown pigment in oxide paints for decorating glazed ceramics. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

Dr. Russell Skowronek grinding, mixing, and weighing oxides for paints, 2007. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

Composite of mayólica patterns reconstructed by Anita Cohen-Williams and Jack S. Williams. (Adapted in 2007 by authors, from “Reconstructing Maiolica Patterns from Spanish Colonial Sites in Southern California,” California Mission Studies Meeting, San Luis Obispo, 2004.)

Mayólica patterns painted by volunteers in 2007 to replicate patterns reconstructed by Cohen-Williams and Williams in “Reconstructing Maiolica Patterns from Spanish Colonial Sites in Southern California.” (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

Dr. Robert Hoover painting a Puebla Blue-on-white sopero, 2007. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

(Left) San Elizario Polychrome sopero (illustrated in Cohen-Williams and Williams, “Reconstructing Maiolica Patterns from Spanish Colonial Sites in Southern California”); (center) San Elizario Polychrome sopero replica painted by Karen Anderson and Toni Clark before firing, 2007; (right) San Elizario Polychrome sopero painted by Karen Anderson and Toni Clark after firing, 2007. (Photos, Michael Imwalle.)

(Left) Replica Tucson Polychrome sopero fired in a sagger; (right) San Elizario Polychrome sopero fired without a sagger, 2007. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.) Note the clear, bright, glossy glaze of the saggered vessel and the dark, dull appearance of the carbon trapped in the unprotected vessel.

Elizabeth Skowronek, our “research assistant,” at the beginning of the project in 2000, holding a 200-year-old escudilla at Mission San Antonio, and in 2010, holding a replicated escudilla. (Photos, Russell Skowronek.) Currently a college student studying engineering, Elizabeth continues to work on aspects of this and related projects.

Two-chamber Spanish-colonial updraft kiln at El Presidio de Santa Barbara State Historic Park during the firing of the mayólica, 2007. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

Assortment of mayólica vessels produced during glazing and painting project, 2007. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

Replicated mayólica apothecary jars on exhibit in the circa-1830s Casa De la Guerra store, Santa Barbara, California, 2009. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

Replicated San Elizario Polychrome soperos on edge in the cupboard (second and third row from top) of the comandancia (commandant’s quarters), El Presidio de Santa Barbara State Historic Park, 2009. (Photo, Michael Imwalle.)

For five years (2009–2014) a bilingual exhibition on the California Pottery Project at El Presidio de Santa Barbara State Historic Park explained the processes of pottery fabrication and analysis. (Courtesy, El Presidio de Santa Barbara State Historic Park, Santa Barbara, California.)

A panel in the exhibition “Ceramics Rediscovered” at El Presidio de Santa Barbara State Historic Park details how instrumental neutron activation analysis can “fingerprint” ceramics. (Courtesy, El Presidio de Santa Barbara State Historic Park, Santa Barbara, California.)