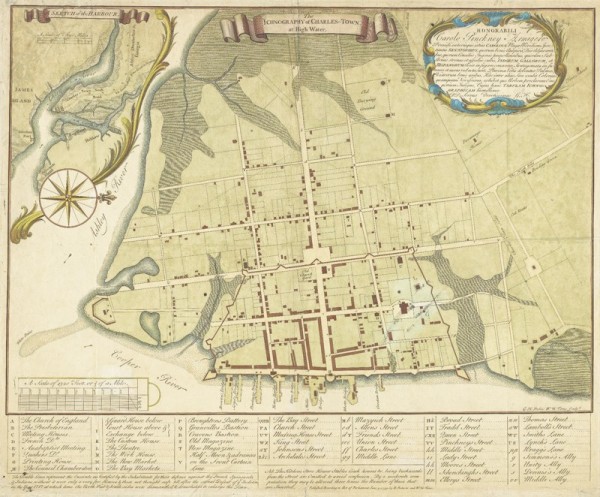

B. Roberts and William Henry Toms, Ichnography of Charles-Town at High Water, London, England, 1739. 13 x 18 3/8". (Courtesy, Brown University.) The map shows the outline of the walled city and growth beyond those fortifications.

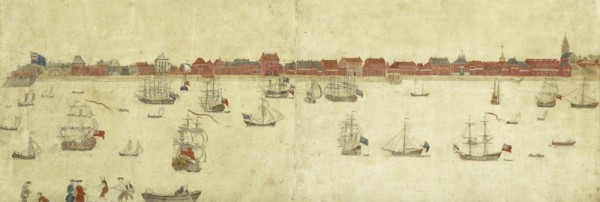

Bishop Roberts, Prospect of Charles Town, watercolor and ink on paper, Charleston, South Carolina, 1737–1738. 18 1/2 x 46 1/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) A fire in 1740 destroyed many of the buildings shown in this view.

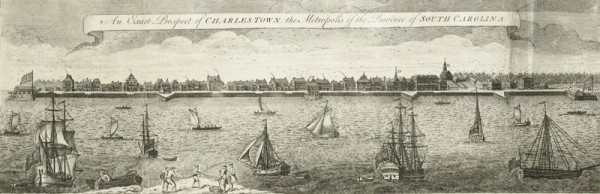

Bishop Roberts (painter) and William Henry Toms (engraver), An Exact Prospect of Charlestown, the Metropolis of the Province of South Carolina, London, England, 1739. 10 1/4 x 23 5/8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) This engraving was based on Roberts’s watercolor illustrated in fig. 2.

John William Hill, Panorama of Charleston, 1851. Hand-tinted lithograph on paper. 24 x 41 1/2". (Courtesy, Gibbes Museum of Art / Carolina Art Association.)

Bowl fragments, Barbados, ca. 1800. Green lead-glazed earthenware. (Codrington Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These were recovered from excavations at Codrington College, St. John, Barbados.

Bowls, Barbados, twentieth century. Unglazed earthenware. D. 6 3/4". (Courtesy, Michael Stoner; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The bowl in front is typical of the modern form of Barbados redware (not of Barbadian clay) that was made for the Barbados tourism industry by Chalky Mount Pottery ca. 1990. The bowl in back is a modern reproduction of a 1690–1700 bowl excavated at Codrington College, St. John, Barbados.

Sarah Stroud Clarke, Drayton Hall Archaeologist and Curator of Collections, excavating a ditch feature that predates the ca. 1750 Drayton Hall. (Courtesy, Drayton Hall Preservation Trust.)

Teapot fragments, attributed to Pieter Adriaensz Kocks, The “Greek A” Factory, Delft, Netherlands, 1705–1720. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Drayton Hall, National Trust for Historic Preservation.)

Teapot, Pieter Adriaensz Kocks, The “Greek A” Factory, Delft, Netherlands, 1705–1720. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 4 3/4". (Courtesy, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.) This rare black delft, which was made for a short period at the beginning of the eighteenth century, was intended to mimic Chinese lacquer.

Building façade of the Planter’s Hotel, Charleston, South Carolina, 1920s. (Collections of The Charleston Museum.) This photo was taken before 1936, when the hotel was converted to a theater on the site of the original 1736 Dock Street Theatre.

Portion of the Dock Street Theatre privy revealed in an elevator shaft. (Courtesy, The Charleston Museum; photo, Martha Zierden.)

Teabowl, Fukien (Fujian) province, China, 1750s. Porcelain. D. 2 15/16". (Collections of The Charleston Museum; photo, Sean Money.)

Jar and bowl, Charleston area, South Carolina, eighteenth century. Low-fired earthenware. H. of jar 6", D. of bowl 11 1/16". (Courtesy, The Charleston Museum; photo, Sean Money.) Typical vessel forms for colonoware are globular jars and open bowls. These vessels were found at the Meeting Street Office site and Heyward-Washington House, respectively.

Colonoware plate fragments, Charleston area, South Carolina, eighteenth century. Low-fired earthenware. D. 7 5/8". (Courtesy, The Charleston Museum; photo, Sean Money.) These unusual colonoware plates are from the Meeting Street Office site (left) and Heyward-Washington House (right). The rim of the vessel on the left features painted black dots reminiscent of delftware; the vessel on the right is impressed with the edge of a cockleshell or unknown tool.

Teapot fragments, John Bartlam, Cain Hoy, South Carolina, 1765–1770. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, The Charleston Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Note the incorporation of the molded Barleycorn design on the panels of the vessel.

Teabowl fragment, John Bartlam, Cain Hoy, South Carolina, 1765–1770. Soft-paste porcelain. Extrapolated h. of bowl 3 15/16". (The Charleston Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Teapots, Yixing, China, (left) ca. 1825; (right) ca. 1750. Unglazed stoneware. H. of left example 3 3/4". (Courtesy, The Charleston Museum; photo, Sean Money.) The fragmentary teapot illustrated on the right was recovered from the ca. 1770 privy fill at the South Carolina Society Hall, Meeting Street.

Pièrre Eugene du Simitiere (b. Pierre-Eugène du Cimetière, 1736–1784), Drayton Hall S.C., dated 1765 on reverse. Watercolor on paper. 8 3/8" x 12 1/2". (Courtesy, J. Lockard Collection; photo, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation and Craig McDougal.) The watercolor depicts the original design and eighteenth-century appearance of Drayton Hall, North America’s earliest example of fully executed Palladian architecture.

Teapot with archaeologically recovered fragments, probably Staffordshire, England, 1765–1770. Unglazed stoneware. H. 4 7/16". (Courtesy, Drayton Hall Preservation Trust and Drayton Hall, National Trust for Historic Preservation.) Modeled after a Chinese Yixing example, this is the only known example of this type of English dry-bodied stoneware found in an American archaeological context.

Punch bowls. (Left) England, ca. 1760. Tin-glazed earthenware. Inscribed: “Success to Trade”. (Right) China, ca. 1760. Chinese export porcelain. D. 11". (Collections of The Charleston Museum; photo, Sean Money.)

Heyward-Washington House, Charleston, South Carolina, ca. 1772. (Photo, Sean Money.) The brick double house built by Thomas Heyward in 1772 was at least the third home on the Church Street site. Excavations by Elaine Herold in 1975–1977 and Martha Zierden in 2002 revealed structures and deposits spanning the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The property is a historic house museum owned by The Charleston Museum.

Earthenwares, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1760–1780. Slip-trailed wares, clouded wares, and lead-glazed earthenware. D. of center dish 9 5/16". (Collections of The Charleston Museum; photo, Sean Money.) The objects in this group were recovered in Charleston, South Carolina.

Pipkin or sauce pot, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1760–1780. Lead-glazed earthenware. L. including handle 9 5/16". (Collections of The Charleston Museum; photo, Sean Money.)

Children’s cups, Staffordshire or Yorkshire, England, 1810–1830. Pearlware, creamware, and whitewares. H. 2 5/8". (Collections of The Charleston Museum; photo, Sean Money.) These cups were archaeologically recovered from Charleston Place, Heyward-Washington House, and the Meeting Street Office site.

Children’s cup, Staffordshire or Yorkshire, England, 1810–1830. Pearlware, D. 2 5/8". Inscribed: “A PRESENT FOR WILLIAM” (Collections of The Charleston Museum; photo by Sean Money.)