Attributed to Jacques Cortelyou, Afbeeldinge van de Stadt Amsterdam in Nieuw Neederlandt (the Castello plan), ca. 1660. (Photo, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, New York Public Library; New York Public Library Digital Collections, https://digitalcollections. nypl.org/items/510d47d9-7c0b-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99, accessed May 20, 2017.) This is a photograph of the manuscript map in the Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana in Florence, Italy. It is the earliest known plan of New Amsterdam, and the only one dating from the Dutch period.

Detail, Totius Neobelgii Nova et accuratissima tabula (the Restitutio-Carolus Allard map), 1674. (Photo, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, New York Public Library; New York Public Library Digital Collections, http://digitalcollections. nypl.org/items/510d47d9-7c40-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99, accessed February 5, 2017.) In 1673 the Dutch reclaimed New York from the English but returned it permanently the following year as part of the treaty that ended the Third Anglo-Dutch War. The canal shown is the Herren Gracht, which is today’s Broad Street.

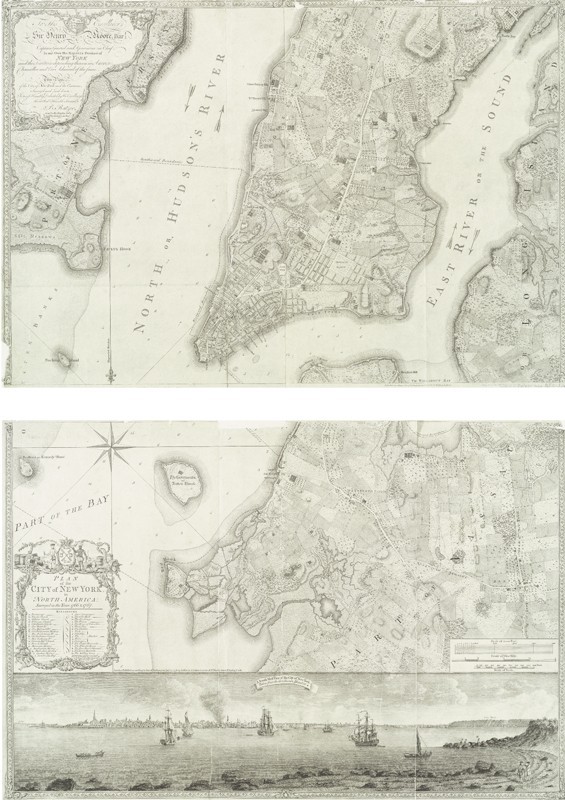

Bernard Ratzer, Plan of the City of New York, in North America, surveyed in the years 1766 and 1767, 1776. The vignette at the bottom is a southwest view of the city, taken from Governors Island in New York Harbor. (Courtesy, New York Public Library.)

Archaeological excavations at the Stadt Huys Block site, 1979. (Photo, courtesy of Nan A. Rothschild.)

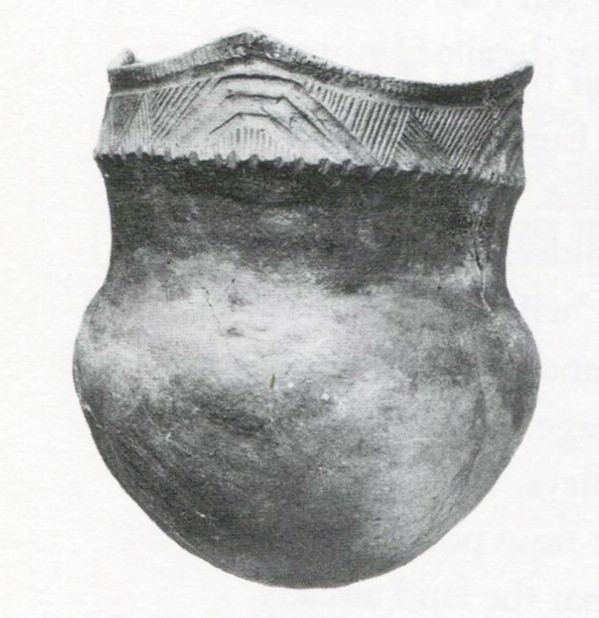

Pot, Late Woodland period, A.D. 900–1600. Low-fired earthenware. H. 13". (Courtesy, National Museum of the American Indian, negative no. 5551.)

William L. Calver, New York City avocational archaeologist, excavating this or a very similar pot at 214th Street and Tenth Ave., 1906. (Photo, Department of Library Sciences, American Museum of Natural History, negative no. 24449.)

Jan Jansz. Buesem (Dutch, ca. 1600–ca. 1649), Peasant Meal, 1625–1650. Oil on panel, 8 1/16 x 11 7/16". (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, SK-A-2555.) A red earthenware pan and porringer sit on the table. On the floor, from left to right, are a small, red earthenware pot with a spout, a small brazier with a square-shaped rim, a pitcher, a large cook pot, and a pitcher with a broken rim.

Cooking pots, Netherlands and possibly New York, ca. 1650–1690. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. of red vessel 4 1/2"; D. 4"; D. of buff vessel 12". (Courtesy, New York City Archaeological Repository of the Landmarks Preservation Commission; photo, Donghyun Kim and Jeanette Miller.)

Nieu Amsterdam, ca. 1643–1650. (The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, New York Public Library; New York Public Library Digital Collections, http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-7c02-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99, accessed February 5, 2017.) The Dutch man on the right is holding tobacco leaves in his left hand. Slaves carry goods in trays balanced on their heads.

Contents of the barrel discovered at the Broad Financial site in Lower Manhattan. This group of artifacts has been tentatively identified as a spirit cache created by an African in the mid-seventeeenth century. (Courtesy, New York State Museum; photo, Josh Nefsky.)

Dish, attributed to Gerrit Willemsz Verstraeten (Dutch, b. ca. 1615), ca. 1650. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 10". (Courtesy, New York State Museum; photo, Josh Nefsky.)

Jan Havicksz. Steen (Dutch, ca. 1625–1679), Tavern Scene, ca. 1661–1665. Oil on canvas, 17 7/16 x 14 1/2". (Courtesy, Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection, on loan © Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, CTB.1957.3.) Stoneware jugs, such as the one seen on the table here, were likely the models for the tavern jugs made by a New York potter using local earthenware clays. The man shown with a pipe has cut tobacco from the roll on the table and is lighting it in a red earthenware brazier that holds smoldering peat. Smoking was a popular activity in New York taverns, based on the number of white clay pipe fragments found in the excavation of King’s House Tavern.

Jugs, New York, New York, ca. 1670–1706. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 8" and 7 3/4". (Courtesy, New York City Archaeological Repository of the Landmarks Preservation Commission; photo, Donghyun Kim and Jeanette Miller.)

Barber’s bowl and basin, Crolius or Remmey potteries, New York, New York, ca. 1730–1775. Salt-glazed stoneware. D. 8 1/2". (Courtesy, New York City Archaeological Repository of the Landmarks Preservation Commission; photo, Donghyun Kim and Jeanette Miller.) The painted motifs are symbols of the barber’s trade: a straight razor, a scissors, and what might be a brush or powder puff.

Philip Dawe and Robert Sayer, The Patriotick barber of New York, or the Captain in the suds, 1775. Mezzotint. Plate 13 3/4 x 9 3/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Museum Purchase, 1946-100.) The incident portrayed is said to have occurred when a barber on Barclay Street refused to finish shaving a customer after the latter was revealed—by the delivery of a letter addressed to “Capn Crozer”—as a British officer. The half-shaven and suds-covered officer was summarily pushed out the door as onlookers laughed. One of the engravings on the wall is of William Pitt (see fig. 16), and wig boxes labeled with the names of local patriots, including Isaac Sears and Jacobus van Zent (Zandt), are piled against the wall and on the floor. The broken bowl on the floor to which the barber is pointing is the same shape as the stoneware one illustrated in fig. 14 but was probably made of refined earthenware.

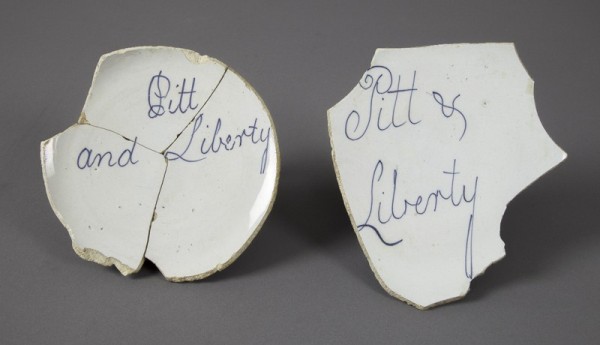

Punch bowl fragments, probably Liverpool, England, ca. 1750–1775. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, New York State Museum; A2005.29C.999.11-12; photo, Donghyun Kim.) These bowls and three others with the same patriotic motto have no wear marks and were probably damaged in transit. William Pitt, an influential member of the British government in the 1750s and 1760s, was popular with American colonists because he opposed the Stamp Act and the Townshend Duties.

Teapot, England, ca. 1765–1783. Creamware. H. 4 1/2". (Courtesy, New York City Archaeological Repository of the Landmarks Preservation Commission; photo, Donghyun Kim and Jeanette Miller.) This enamel-decorated “chintz-style” vessel was likely a personal possession of a British officer. Vessels with this sort of decoration have been attributed to either the Leeds or Greatbatch potteries, decorated by David Rhodes or in his style.

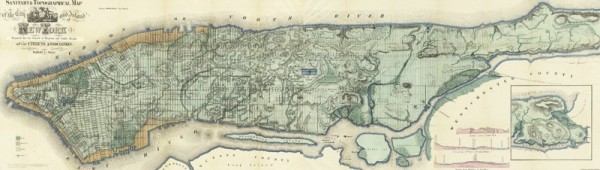

Egbert Viele, Sanitary & Topographical Map of the City and Island of New York (the Viele map), 1865. (Courtesy, David Rumsey Map Collection.) This map shows the extent of landfill along the shores of Manhattan Island prior to that year.

Small bowl, possibly Wood and Caldwell, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1801–1809. Pearlware. D. 10 1/2". (Courtesy, New York City Archaeological Repository of the Landmarks Preservation Commission; photo, Donghyun Kim and Jeanette Miller.) A number of objects in this pattern were part of a shipment that likely was damaged in transit and dumped into the fill of Whitehall Slip.

Teabowl and saucer, China, ca. 1785–1810. Porcelain. D. 3 1/2". (Courtesy, New York State Museum, A2005.29A.1544.83, 84; photo, Donghyun Kim.) Two teacups and three saucers with the enameled motif of two lovebirds on a bar were found in a deposit probably associated with the Bowne family, whose residence and druggist shop was on Hanover Square during the early nineteenth century. Teawares with this lovebird motif were often given as marriage gifts, according to David Sanctuary Howard, New York and the China Trade (New York: New-York Historical Society, 1984), pp. 95–96.

Teapot, Thomas, John, and Joseph Mayer, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, 1842–1855. Whiteware, printed “Florentine” pattern. H. 6 1/2". (Courtesy, New York City Archaeological Repository of the Landmarks Preservation Commission; photo, Donghyun Kim and Jeanette Miller.) Printed motifs purportedly showing images of faraway European or Asian scenes evoked the romance of foreign locales for both English and American consumers.

Teacup and saucer, Spode, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1810–1833. Whiteware, printed “Geranium” pattern. H. of teacup 2 1/4", D. of saucer 5 1/2". (Courtesy, the New York State Museum, A2005.29G.999.2, 3; photo, Donghyun Kim.)

Plate, unknown maker, probably England, ca. 1830–1850. Whiteware, printed “Willow” pattern. D. 9 7/8". (Courtesy, the New York State Museum, A2005.29G.999.4; photo, Donghyun Kim.) All were found in a ca. 1840–1850 deposit.

Plate, Thomas, John, and Joseph Mayer, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, 1842–1855 (possibly 1846–1855). White granite. D. 8". Marked “T.J. & J. Mayer’s Berlin Ironstone.” (Courtesy, the New York State Museum, A2005.29G.999.30; photo, Donghyun Kim.)

Teacup and saucer, probably French, ca. 1840–1860. Hard-paste porcelain with painted gilded motif. H. of teacup 3 1/4". (Courtesy, the New York State Museum, A2005.29G.331.2, A2005.29G.348.2; photo, Donghyun Kim.)

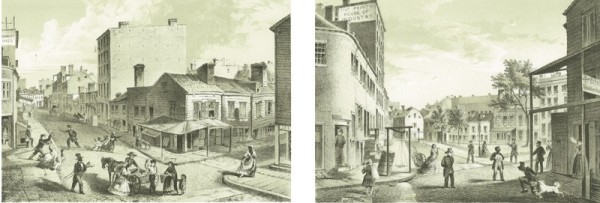

The Five Points in 1859: Crossing of Baxter (late Orange) Park (late Cross) and Worth (late Anthony) Sts.; The Five Points in 1859: View Taken from the Corner of Worth and Little Water St., 1860. (Photo, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library; New York Public Library Digital Collections. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-26ef-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99, accessed February 5, 2017.)

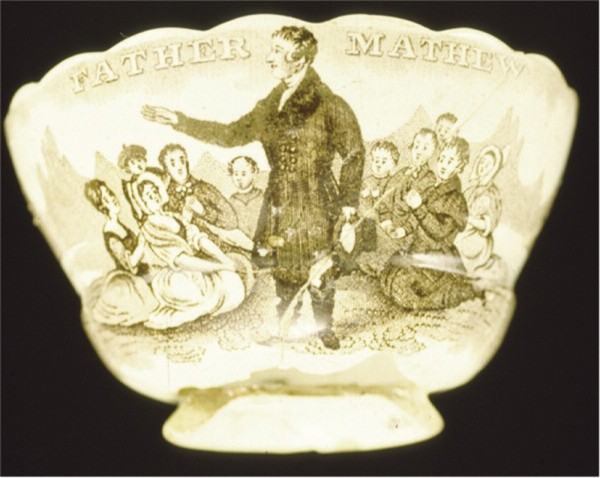

Teabowl, William Adams and Sons, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, ca. 1838–1861. Whiteware, printed “Father Mathew” pattern. H. 3 1/4". (Courtesy, Museum of the City of New York.) This image, printed in other colors in addition to brown, depicts Father Theobald Mathew, an Irish priest who became president of the Cork Total Abstinence Society in 1838, preaching to his flock about the virtues of temperance. He came to America on speaking tours in 1849 and 1851, and addressed at least one large crowd at City Hall near the Five Points.