Left: Jug, Robert and Thomas Swaine, Prescot, Merseyside (Lancashire), England, ca. 1825. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 16 5/8". Mark: SWAINE. Center: Bottle, probably Frechen, Germany, ca. 1660–1680. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8 1/2". Right: Flagon, probably Frechen, Germany, mid-eighteenth century. Salt‑glazed stoneware. H. 12 1/2". (Author’s collection; unless otherwise noted, all photos by Jason Dowdle.)

Jug, attributed to Peter Herrmann, Baltimore, Maryland, ca. 1870s–1880s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9". Mark: SLADE.JONES.&.CO / DEALERS IN GENERAL / MERCHANDISE / HAMILTON. NC (Author’s collection.)

Jug, Salisbury, Rowan County, North Carolina, ca. 1755–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware with copper and manganese oxides. H. 10 1/2". (Author’s collection.) This jug fragment was found beneath a Salisbury building during its demolition. Similarly colored ware has been collected nearby.

Left: Standing-eagle bottle, attributed to Rudolph Christ, Salem, Forsyth County (Stokes County before 1849), North Carolina, ca. 1800–1821. Lead-glazed earthenware with copper oxide. H. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) Right: Turtle bottle, attributed to Rudolph Christ, Salem, Forsyth County, North Carolina, ca. 1800–1821. Lead-glazed earthenware with colored oxides. L. 8 1/2". (Author’s collection.)

Left: Standing flask, Alamance County, North Carolina (old St. Asaph’s District, Orange County), ca. 1770–1790. Lead-glazed earthenware with slip-trailed decoration. H. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) Right: Bottle, Alamance County, North Carolina, ca. 1790–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware with slip-trailed decoration. H. 6". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Left: Jug, Jamestown, Guilford County, North Carolina, dated 1834. Salt‑glazed stoneware. H. 15 3/4". Marks: “10” and “1834”. (Courtesy, Richard and Carol Hay.) Right: Jug, Nathan B. Dicks, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1890. Lead-glazed earthenware.

H. 5 1/2". Mark (inscribed): N. B. DICKS new market n.c. Jan 12 1890 1 Pt. (Courtesy, Elizabeth Edmonds.)

Ten-gallon, two-handle jug, Daniel Seagle, Lincoln County, North Carolina, ca. 1840–1850. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 16". Mark: D.S. 10 (From Nancy Sweezy and Mark Hewitt, The Potter’s Eye: Art and Tradition in North Carolina Pottery [Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006]. Used by permission of the publisher.)

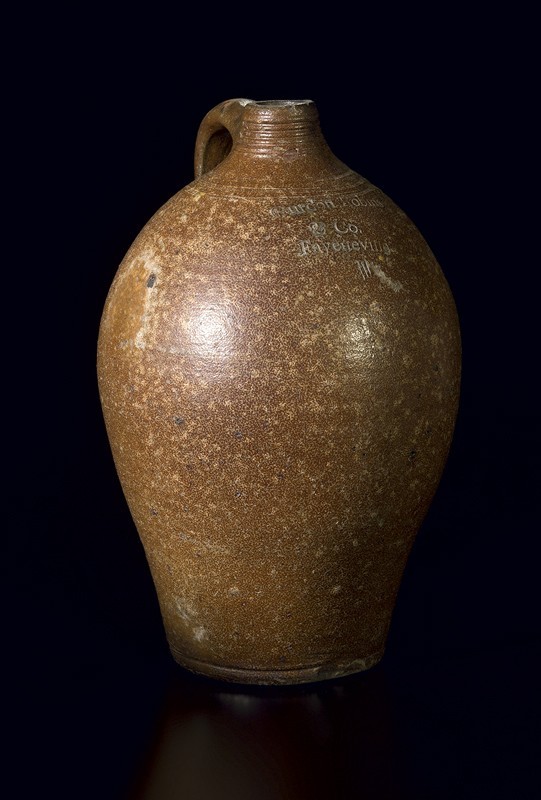

Three-gallon jug, attributed to Edward Webster, Fayetteville, North Carolina, ca. 1820–1823. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 16 5/16". Mark: Gurdon Robins & Co. Fayetteville III (Courtesy, Quincy Scarborough.)

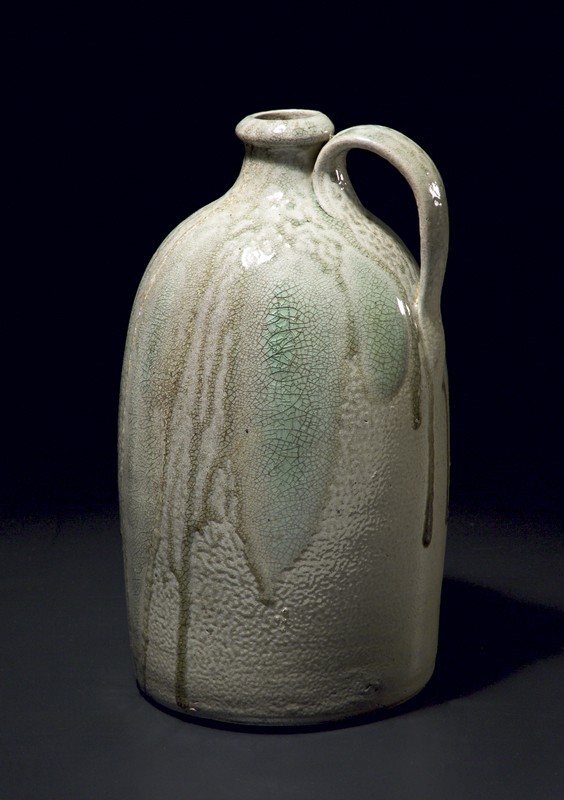

Four-gallon jug, attributed to Chester Webster, Randolph County, North Carolina, ca. 1840–1882. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 18". (Courtesy, Tommy and Ann Cranford.)

Left: Jug, John Anderson Craven, Randolph County, North Carolina, ca. 1850. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15". Mark: J.A.C. (Courtesy, David Ward.) Right: Jug, possibly Edward Stone, Buncombe County, North Carolina, ca. 1850–1870. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 6 1/4". (Courtesy, Rodney H. Leftwich.) The glassy greenish-brown runs might be the result of applied slab glass. Most fly-ash runs are coincidental to a jug’s manufacture, yet they are so commonly found on North Carolina jugs that some effort may have been made to encourage them to satisfy customers’ preferences. The intentional addition of slab glass before firing was a simple way to add color and texture to a vessel’s surface.

Jug, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, ca. 1830–1860. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 13". (Collection of Robert and Jimmie Hodgin; photo, Nancy Sweezy and Mark Hewitt, The Potter’s Eye: Art and Tradition in North Carolina Pottery [Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006]. Used by permission of the publisher.)

Jug, Nicholas Fox, Chatham County, North Carolina, ca. 1818–1858. Salt-glazed stoneware with incised circumferential bands. H. 19 1/2". Mark: N FOX [twice]. (Courtesy, North Carolina Pottery Center.) Highlighted by a distinctive salt-glaze “orange peel” surface and incidental kiln arch drips, this sturdy and handsome jug exemplifies the best of North Carolina’s eastern Piedmont stoneware production. Jugs made by Nicholas and his son Himer often bore an impressed Masonic “square and compass” symbol, suggesting that the potters were Freemasons.

Jug, William Nicholas Craven, Randolph County, North Carolina, ca. 1845–1857. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14 11/16". Marks, in cobalt blue (inscribed): S[t]ate / of nc / randolph / county; (stamped): W.N. CRAVEN (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Jug, David Hartzog, Lincoln County, North Carolina, ca. 1830–1840. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 12 7/8". Mark: DAVIDHARTZOGHISMAKE. [The 'S' is backwards.] (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

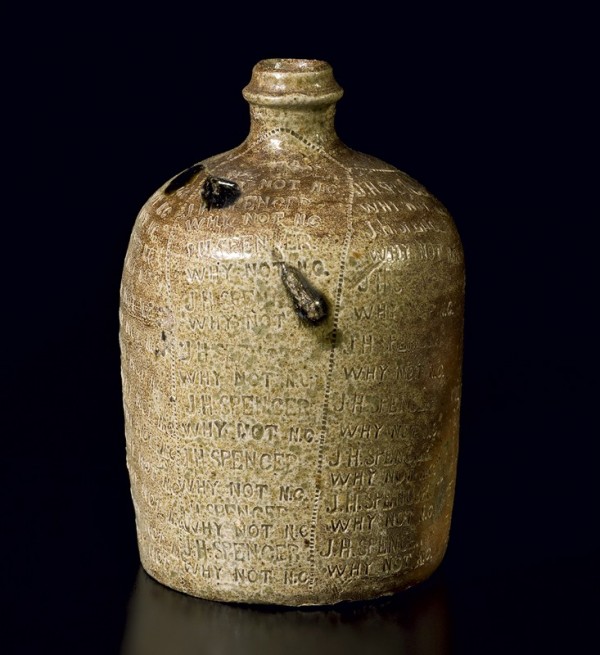

Bottle, Jordan Harris Spencer, Why Not, Randolph County, North Carolina, ca. 1868-1926. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8". Mark: J. H. SPENCER / WHY NOT N.C. [multiple times]. (Courtesy, Tommy and Ann Cranford.)

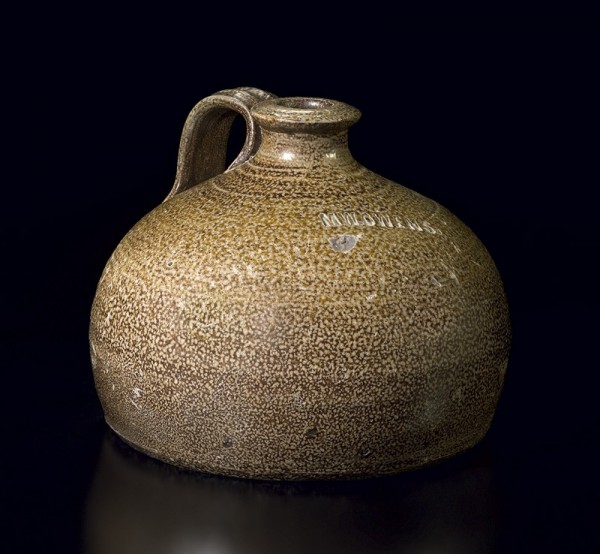

Buggy jug, Manley William Owen (or Owens), Randolph County, North Carolina, ca. 1880–1900. Salt‑glazed stoneware. H. 5 1/2". Mark: MW. OWENS. (Author’s collection.) As its name indicates, this modified tall jug was made short and wide, ensuring its stability when placed on the floorboards of a buggy or wagon.

Left: Rundlet, Nathaniel H. Dixon, Chatham County, North Carolina, ca. 1848–1863. Salt-glazed stoneware. L. 11". Mark: N. H. DIXON. (Courtesy, Steve Garner.) Right: Rundlet with bail handle, possibly Baxter Welch pottery shop, Harpers Crossroads area, Chatham County, North Carolina, mid-nineteenth century. High-fired earthenware. L. 7 1/2". (Author’s collection.) Rundlets were popularly used for transportation and storage of whiskey, beer, cider, and brandy. Some, like the smaller one seen on the right with a pouring spout protruding from its bung hole, could also be used for serving in a home or tavern.

Ring bottles. Left: Piedmont region, North Carolina, late eighteenth–mid-nineteenth century. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 9". (Author’s collection.) Right: William Henry Hancock, Moore County, North Carolina, ca. 1865–1900. Salt-glazed stoneware. D. 8". Mark: W. H. HANCOCK (Courtesy, North Carolina Pottery Center.) A footed ring-bottle form, allowing the jug or bottle to stand upright, is also known.

Jugs, James Otis Trull, Buncombe County, North Carolina, 1911–1912. Left: Single-chamber monkey jug, dated September 15, 1911. Albany slip–glazed stoneware. H. 9 3/4". Mark (inscribed): Sept 15 1911 Preasented by J O Trull (Courtesy, Rodney H. Leftwich.) Right: Long-necked jug, dated August 1912. Albany slip–glazed stoneware with fly-ash highlights. H. 7". Mark (inscribed): Made By J. O. Trull for C. B. Brock Candler R.F.D. August 1912 (Author’s collection.) No one knows with certainty how the term monkey jug came to be applied to a bulbous-bodied jug with a strap handle overhead and multiple openings. Similar jugs are common in Spain, Africa, and the Caribbean. Typically, one spout is for pouring and the other opening allows air to come in, improving the outflow of the jug’s contents.

Double-chambered monkey jugs, Vale, North Carolina. Left: attributed to William D. Bass, 1900–1935. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 9 1/2". (Courtesy, North Carolina Pottery Center.) Right: Harvey or Enoch Reinhardt, Reinhardt Bros. Pottery, ca. 1932–1936. Agateware (swirl) with clear glass glaze. H. 10 7/8". Mark: REINHARDT BROS. / VALE, N.C. (Author’s collection.) Like other, more whimsical jug shapes, there is no clear explanation for why some potters made double‑chambered monkey jugs.

Left: Saddle jug, Thomas Ritchie, Lincoln or Catawba County, North Carolina, ca. 1846–1900. Alkaline‑glazed stoneware. H. 7 1/2". Mark: TR 2 (Courtesy, Scott and Wendy Smith.) Right: Pinch bottle with cup/lid, Lincoln or Catawba County, North Carolina, late nineteenth–early twentieth century. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 6 3/4". (Author’s collection.)

Puzzle jug, Baxter Welch Pottery, Harpers Crossroads, Chatham County, North Carolina, ca. 1900. Salt‑glazed stoneware. H. 8 1/4". (Courtesy, Quincy Scarborough.) A purely whimsical form, this jug has a single spout but three miniature jugs masterfully mounted to its top. None of the small jugs opens into the larger host jug, which disqualifies it from being a true puzzle jug in the way of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century European examples. Nevertheless, someone three sheets to the wind might be amusingly befuddled when chasing a swig from this peculiar jug.

A typical moonshine still. (From Margaret W. Morley, The Carolina Mountains [1913]; photo, Courtesy of the State Archives of North Carolina, N71.11.153.)

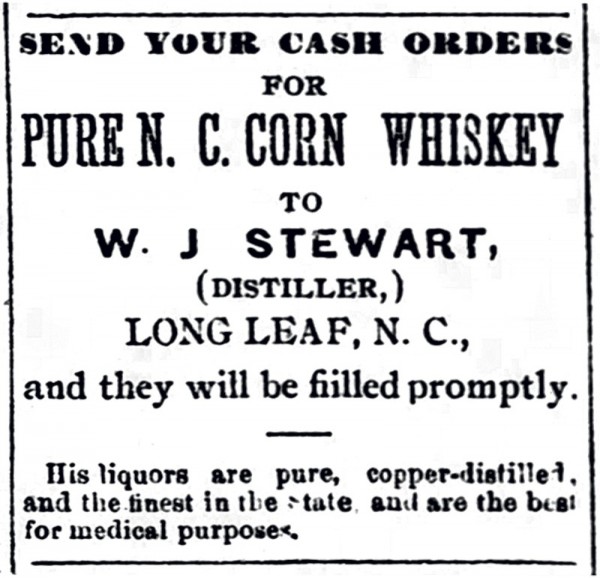

Advertisement for W. J. Stewart, potter and distiller, of Long Leaf, Moore County, North Carolina, who reportedly made whiskey on one side of his creek and jugs for it on the other side. (From The Carthage [N.C.] Blade, May 9, 1893.)

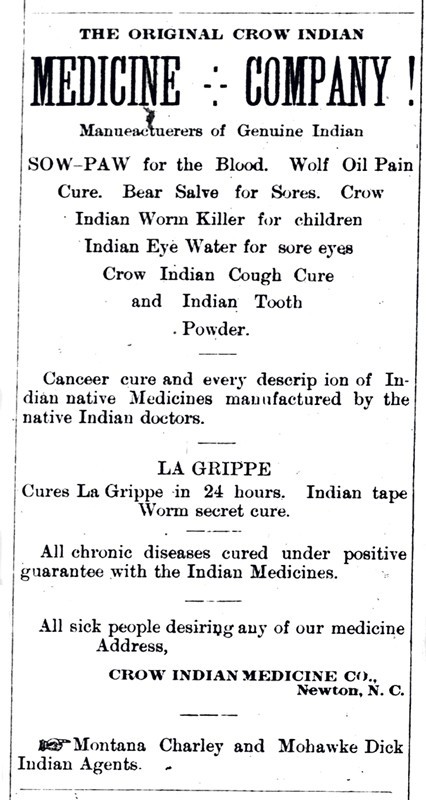

Advertisement for Crow Indian Medicine Co.’s Genuine Indian Sow Paw in Raleigh (N.C.) Signal, September 26, 1891.

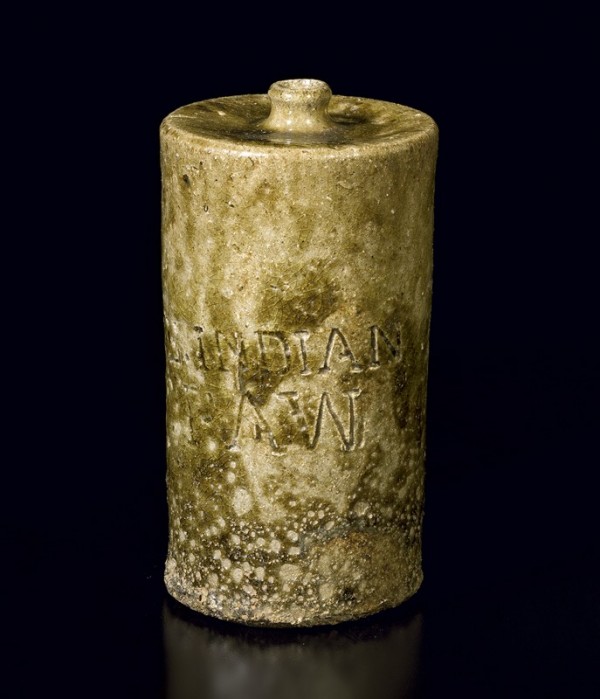

Patent-medicine bottle, Lincoln or Catawba County, North Carolina, ca. 1892. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 6". Mark: GENUINE INDIAN / SOW PAW. (Courtesy, Scott and Wendy Smith.)

Jug, Luther Seth Ritchie, Catawba County, North Carolina, ca. 1895–1905. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 8 1/4". Mark: FROM J. C. SOMERS STATESVILLE, N.C. (Courtesy, L. A. and Suzan Rhyne.)

Stacker, or shoulder jugs. Left: ca. 1900. H. 11". Mark (incised): Lamort & Golay / Tryon N.C. (Courtesy, Scott and Wendy Smith). Center: C. C. Ballard, Wilkes County, North Carolina, ca. 1880. H. 8 1/4". (Author’s collection.) Right: ca. 1885–1900. H. 10 1/2". Mark (incised): Jay Bradley / Best Copper Distilled / Corn & Rye Whiskies / Jarretts / N.C. (Courtesy, Pem Woodlief.) Lamort and Golay were vintners and wine distributors in Tryon, Polk County, N.C. Jay Bradley operated a saloon in the state’s mountainous Nantahala Valley, at Jarretts, N.C., where he also produced corn and rye whiskey. The potter C. C. Ballard produced a hand-turned stacker jug festooned with a slab of glass melted over one side. In the early part of the twentieth century, Wilkes County, where the Ballard jug was made, was noted for its moonshining. The region’s fast-driving bootleggers triggered the creation of NASCAR racing.

“Swiglet” jugs, attributed to Auman Pottery, Seagrove, Randolph County, North Carolina, ca. 1928. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. of both 3 1/4". Marks (inscribed): Left, Al Smith; right, REGARDS TO O. J. COFFIN SHUCKS AND NUBBINS Z. H. RUSH (Author’s collection.)

Kennedy Pottery, North Wilkesboro, Wilkes County, North Carolina, ca. 1933. (Courtesy, Charles G. Zug III; photo, Ray A. Kennedy.) Claude L. Kennedy (left), Bulo Jackson Kennedy (center), and Converse Harwell mockingly pretend to pour their jug’s intended product into mugs of their own manufacture. For many years, the Kennedys, who employed a bevy of skilled potters, supplied jugs of many sizes to nearby moonshiners and government-licensed distillers.

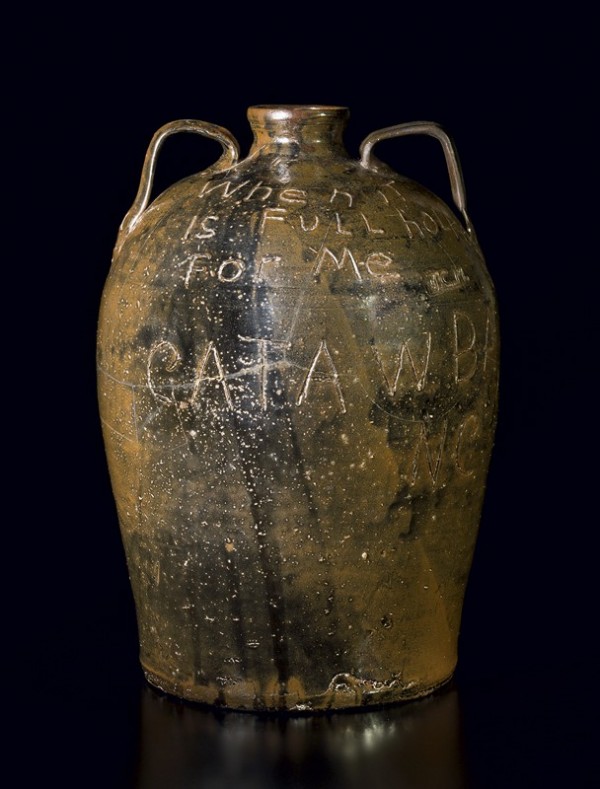

Five gallon, two-handle jug, T. Casey Meaders, Catawba, Catawba County, North Carolina, ca. 1922–1940. Albany slip glazed stoneware. H. 17 3/4". Marks (inscribed): When IT / IS FULL hollow [holler] / For Me / T.C.M. / CATAWBA / N.C.; on opposite side: Mr. Will Hedrick On The Road To Cat-fish. (Courtesy, L. A. and Suzan Rhyne.)

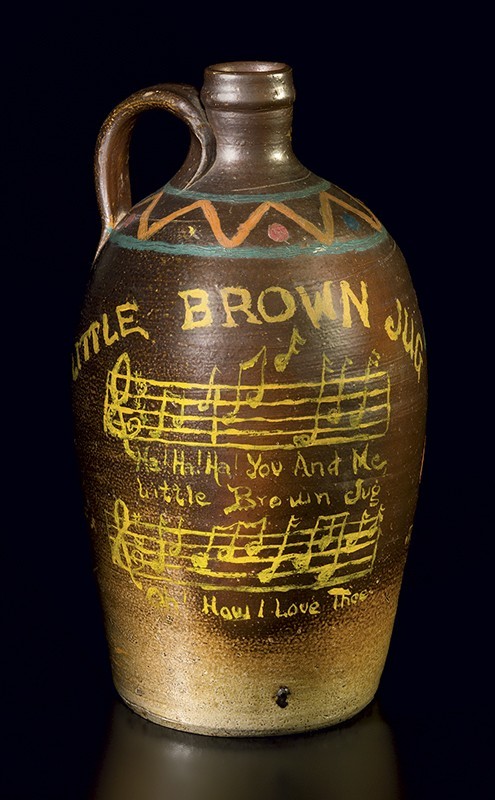

Jug, Jacob Dorris Craven, Randolph County, North Carolina, ca. 1860–1890. Albany slip-glazed stoneware. H. 12". Mark: J. D. CRAVEN (Author’s collection.) Decorated with painted-on chorus from the song “The Little Brown Jug,” words and music by Joseph Eastburn Winner, circa 1869. Originally written as a drinking song, “The Little Brown Jug” retained its popularity for many decades, including the years of Prohibition. In 1939 Big Band leader Glenn Miller recorded one of the best-known versions of it.