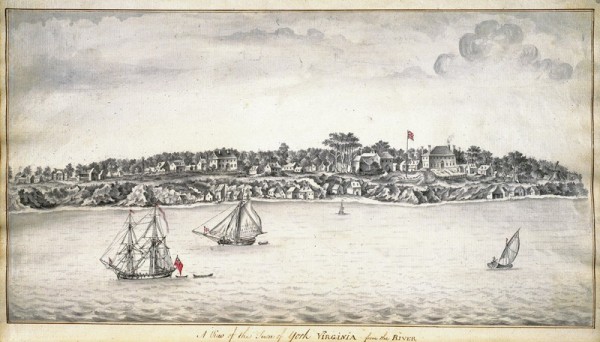

View of the Town of York Virginia from the River, 1754–1756. Colored drawing from Logbook #406 Voyage of HMS Success and HMS Norwich to Nova Scotia and Virginia. (Courtesy, The Mariner’s Museum.) Despite its industrial character, the William Rogers pottery was situated just one block from Yorktown’s Main Street and within eyesight of the town’s grandest residences.

Earthenware and stoneware “wasters” recovered from the William Rogers site in Yorktown, Virginia, ca. 1720–1745. (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park, Yorktown Collection.)

View of the archaeological excavations of the main workshop of the William Rogers pottery building complex, facing north. (Photo, Norman F. Barka.)

An oblique view photograph of the large kiln at the William Rogers pottery. These are the best preserved remains of an eighteenth-century stoneware kiln in America. (Photo, Norman F. Barka.)

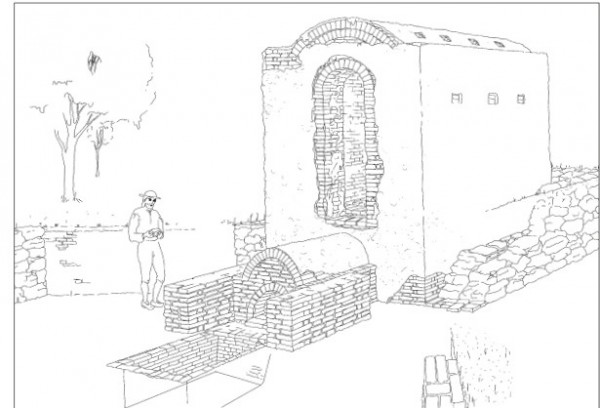

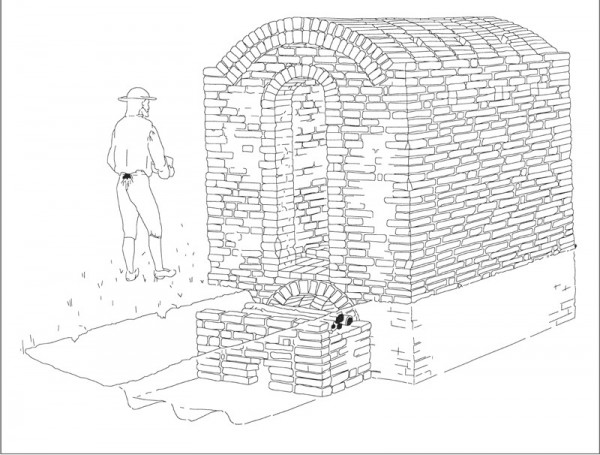

An artist’s reconstruction of the large kiln at the William Rogers pottery. (Drawing, Toni Gregg.).

View of the smaller of two kilns excavated at the William Rogers pottery. (Photo, Norman F. Barka.) The kiln is 5'6" high.

An artist’s reconstruction of the small kiln at the William Rogers pottery. (Drawing, Toni Gregg.)

Milk pans, William Rogers pottery, Yorktown, Virginia, 1720–1745. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 14". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park, Yorktown Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Mugs, William Rogers pottery, Yorktown, Virginia, 1720–1745. Salt‑glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park, Yorktown Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

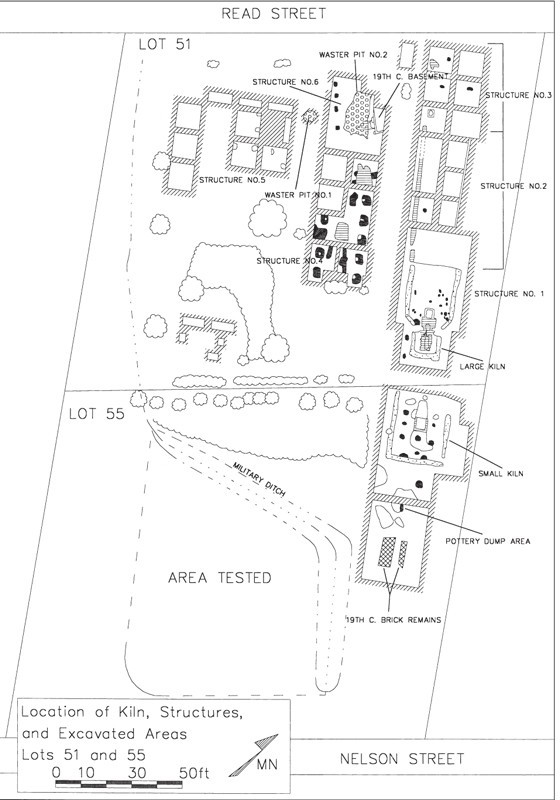

A plan drawing of the excavations detailing the locations of the kilns and related structures and features of the William Rogers pottery.

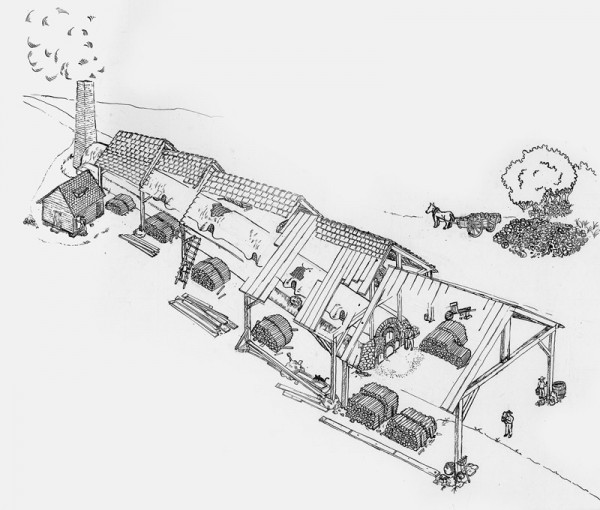

Artist’s reconstruction of the William Rogers pottery (ca. 1720–1745) in Yorktown, Virginia. (Drawing, Cary Carson.)

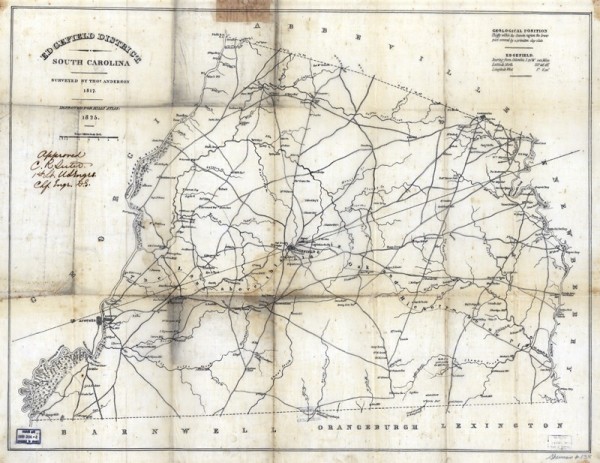

Mills Atlas of South Carolina, ca. 1825. These tracings, by the U.S. Army, are ca. 1860.

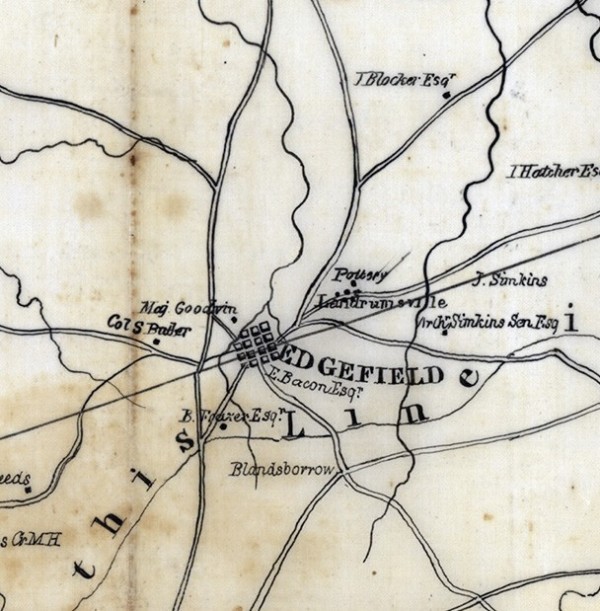

Detail of the map illustrated in fig. 12 showing the Edgefield community and the Landrum pottery to the northeast.

Bottle, Abner Landrum, Edgefield County, South Carolina, dated 1820. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 8". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) This small bottle is incised “July 20th 1820 / A. Landrum.” It is one of the earliest known pieces of dated Edgefield stoneware, and the only known example signed by Abner Landrum.

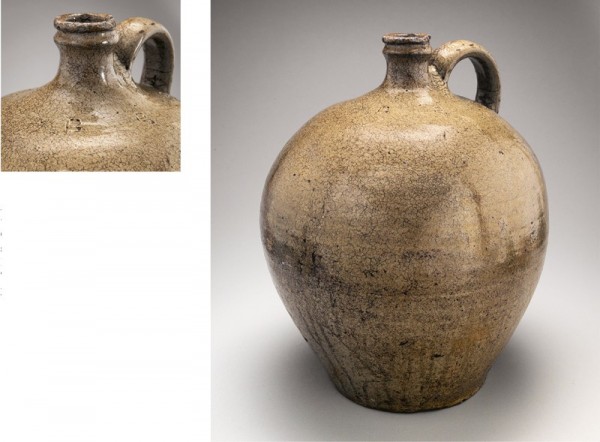

Storage jar, attributed to Pottersville, Edgefield, South Carolina, dated 1821. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) One of the earliest dated production vessels, this well-formed two-gallon storage jar is inscribed “1821” and further embellished with a series of circular punctates.

Storage jar, attributed to Pottersville, Edgefield, South Carolina, dated 1822. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) Another early dated example, this two-gallon storage jar is inscribed “July the 30th 1822.” In addition, it is stamped with seven “B”-like marks.

Storage jar, attributed to Pottersville, Edgefield, South Carolina, ca. 1820–1822. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) The jug has four stamped “B”-like marks, identical to those on the jar illustrated in fig. 16.

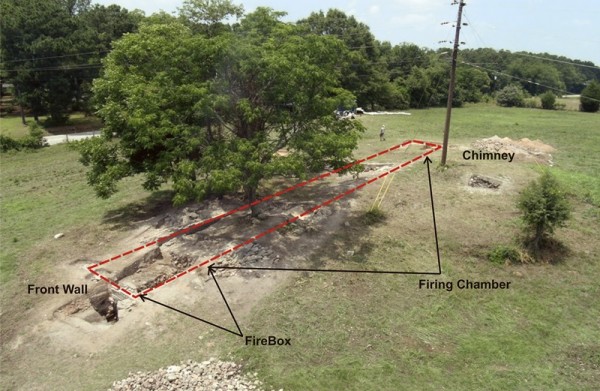

Excavated remains of the Pottersville kiln in 2011, with key architectural features indicated. (Photo, George Calfas.)

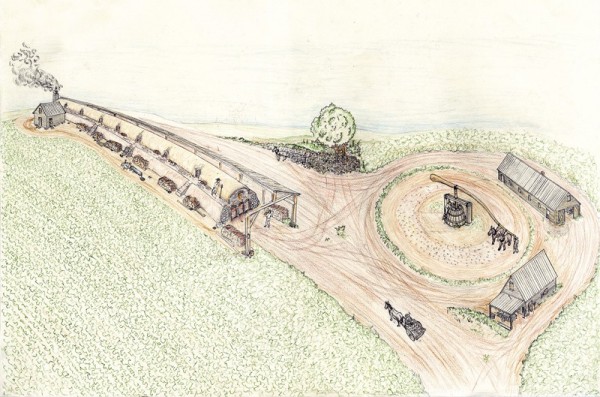

Conjectural reconstructive drawing of the Pottersville kiln. (Drawing, Oliver Mueller-Heubach.)

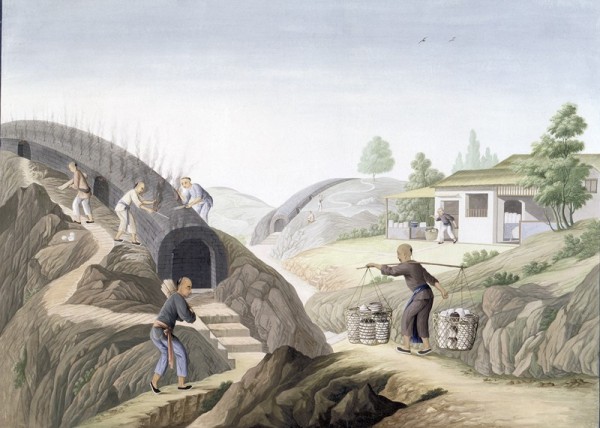

Painting of a dragon kiln, China, ca. 1825. Gouache on paper. 20 7/8 x 15 3/8". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex; Museum purchase with funds donated anonymously, 1983, E81592.14.)

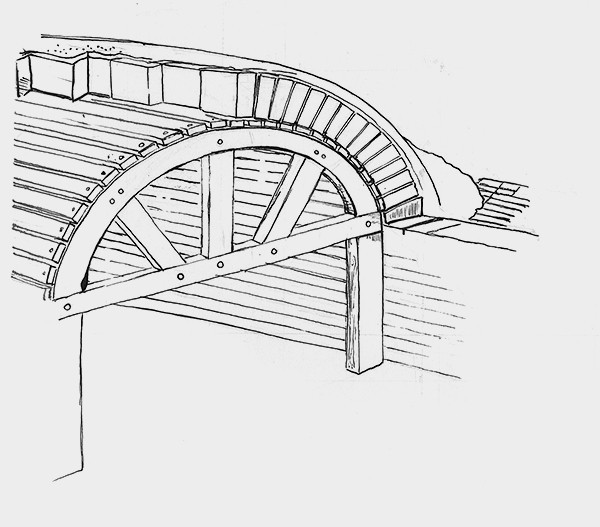

A conjectural drawing suggesting how the kiln’s catenary arch might have been constructed using a wooden form that was subsequently removed after the bricks were laid. (Drawing, Oliver Mueller-Heubach.)

Storage jar, Lewis Miles pottery, Edgefield, South Carolina, dated 1840. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 15 1/2". (Harvard Art Museums; photo, Robert Hunter.) This six-gallon jar is inscribed “January 27th 1840” and “Mr Miles Dave” with punctuates and slashes. It is a highly important example of David Drake’s work, the earliest known example signed with his name, “Dave.”

Conjectural reconstructive drawing of the Pottersville kiln. (Drawing, Oliver Mueller-Heubach.)

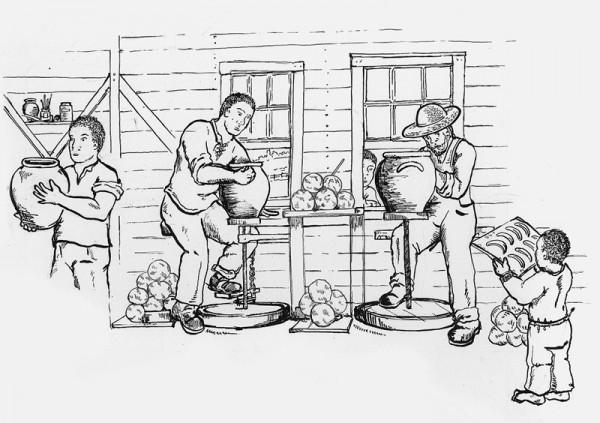

Conjectural drawing of workshop activities at Pottersville showing the throwing of large jars. (Drawing, Oliver Mueller-Heubach.) Activities were organized in an assembly-line fashion with individuals assigned specific tasks such as preparation of clay balls for throwing and handle making.

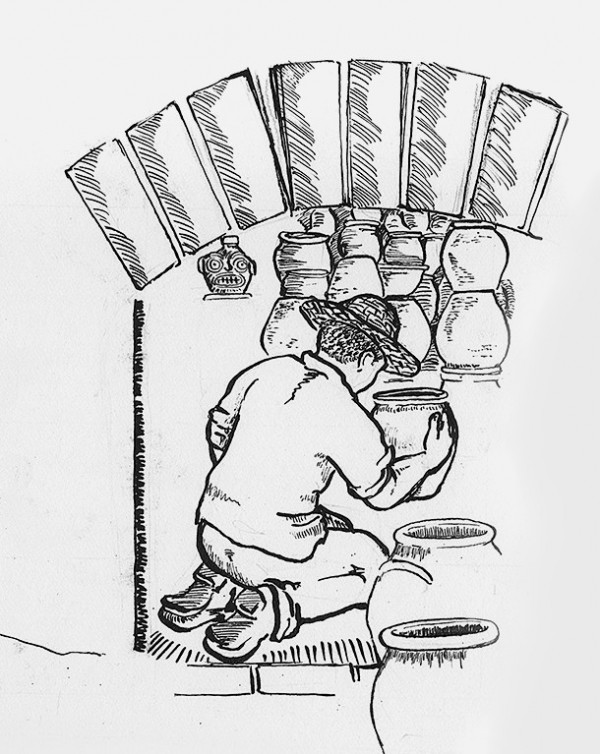

Loading the kiln. (Drawing, Oliver Mueller-Heubach.) The loading of the kiln was one of the most critical aspects of the entire manufacturing progress.

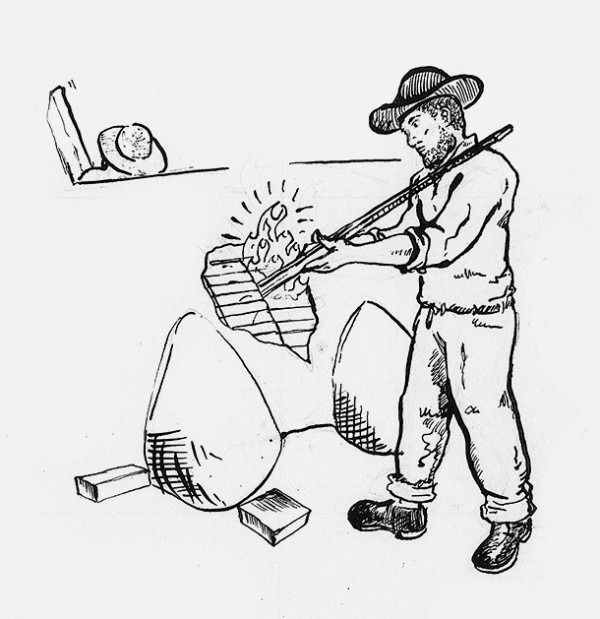

Conjectural drawing of workers stoking the side ports of the kiln. (Drawing, Oliver Mueller-Heubach.) The fuel used for these side ports was generally smaller than the larger planks used in the main firebox.