Pipe bowl, recovered from 44WM12, Westmoreland County, Virginia, 1647–1672. Earthenware. H. 1 5/8". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Brian Palmer.) Recovered from the Nomini Site, the “Angel Deer of Nomini” is arguably the finest artwork from the early Virginia colony. Algonquians commonly used this “Quadruped” motif. This thumb-sized example was created with a rectangular-toothed stamp, probably cut with European tools. Given the “Creole” nature of the colony, the only certain attribution is that the creator had Native American, or European, or African roots.

Pierre Pena and Mathias de l’Obel, Stirpium adversaria nova (London: Thomas Purfoot, 1571), p. 252. This is the earliest English print depicting tobacco being smoked. The caption states a palm leaf was used to wrap the weed.

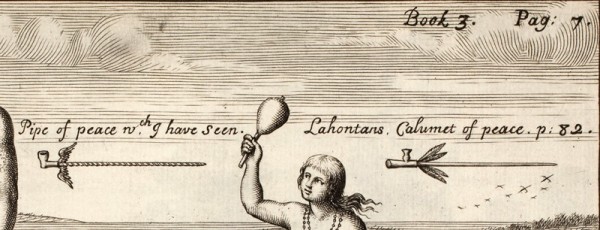

Engraving from Robert Beverly, The History of Virginia, in Four Parts, 2nd ed. (London: Printed for B. and S. Tooke, 1722), pt. 3, p. 145. (Courtesy, Library of Congress.) Beverly’s History of Virginia provides a 1705 record of Native pipes with bowls attached to reed stems (calumet is a French word for reed). Beverly lived in the vast “Virginia” claimed by the Elizabethans, and he included excerpts from the Baron de Lahontan’s description of New France while basing this engraving on John White’s images of the Roanoke Island area. Carolus Clusius credited White’s 1585 expedition with carrying back the Indian pipes, which started the British clay-pipe industry.

Pipe bowl, Aquia Landing, Stafford County, Virginia, probably Late Woodland, ca. 1600. Earthenware. H. 2 3/16". (Private collection; photo, Laura Powell Kiser.) This bowl, with its reed stem long since vanished, belongs to a ceremonial pipe of the Patawomeck people. A horizontal band of chevrons is faintly visible below the rim, while its ringed surface hints of Iroquoian style in the Algonquian world. A storm revealed this pipe in 1997, whereupon it was returned to the care of a Patawomeck chief.

Pipe bowl, recovered from 44PG51, Prince George County, Virginia, ca. A.D. 1300 or earlier. Earthenware. H. 1 3/8". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Katherine Ridgway.) In the mid-Atlantic United States, the earliest known smoking implements are tubes. Some later types had one end closed down to a small hole for sucking out the smoke. In one variation, that tapering end grew into a stemmed “elbow” pipe. Although shattered, most of this pipe was recovered, implying it may have been ritually destroyed, or “killed.”

Pipe bowl, recovered from 44BO3, Botetourt County, Virginia, probably Late Woodland, ca. 1600. Earthenware. H. 1 1/8". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Katherine Ridgway.) This pipe probably dates to the Late Woodland, before the arrival of English colonists, and was excavated from a possible Siouan site many miles inland on the Roanoke River. This Native form is believed to have served as the prototype for the very first English pipes, rounded “belly” bowls, which appeared in the 1580s. The origin of the English clay-pipe industry is credited to a 1585 expedition which may have traveled up the Roanoke River as far as today’s Roanoke Rapids.

Pipe bowl, probably London, ca. 1607–1610. Earthenware. L. 2 3/4". (Courtesy, Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation [Preservation Virginia]; photo, Michael Lavin.) Excavated from the 1610 well of James Fort, this “belly” bowl is one of the very first European clay tobacco pipes, made for smoking the expensive new “miracle drug.”

Tobacco pipe, Robert Cotton, Jamestown, Virginia, ca. 1608–1610. (Courtesy, Jamestown Rediscovery [Preservation Virginia]; photo, Michael Lavin.) These were made at James Fort by Robert Cotton, the very first Anglo-American pipe maker. Cotton may have been a London-trained pipe maker, but he did not use a European-style mold in Virginia. These hand-built works are statements of cultural fusion, an Algonquian-style elbow bowl turning into an octagonal stem that goes round, like a European musket barrel.

Pipe, recovered from 44PG302, Prince George Country, Virginia, ca. 1619–1635. Earthenware. H. 1 1/4". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Katherine Ridgway.) Excavated from Cecily Jordan Farrar’s well at Jordan’s Point on the James River, this was probably made by a Siouan speaker. It has the typical undecorated stem of a Native pipe, with Algonquian-style bands stamped around the bowl, along with a single hanging triangle. The stamp had rectangular teeth, possibly cut with European tools. Traces of white infill make this one of the two earliest datable examples of that decoration. Elizabeth Bollwerk most often found sculptural elaboration and inverted rims on Iroquoian and Siouan sites, but acute carination is more typical on sites believed to have been Siouan.

Pipe bowl, recovered from 44SK56, Suffolk, Virginia, ca. 1640. Earthenware. H. 1 7/16". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Katherine Ridgway.) Although found in Suffolk, an Algonquian area, this was probably made by an Iroquoian speaker. “Ring” bowls with impressed surfaces are common in the northeastern U.S., but relatively rare south of Pennsylvania.

Tobacco pipe stems, Bookbinder, Virginia, ca. 1640. Earthenware. (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Taft Kiser.) The remarkably strict decorative grammar of Bookbinder pipes makes it almost certain they were the products of a single individual. That person apparently lived in Virginia Beach, and may have been trained as a pipe maker in Britain or the Netherlands.

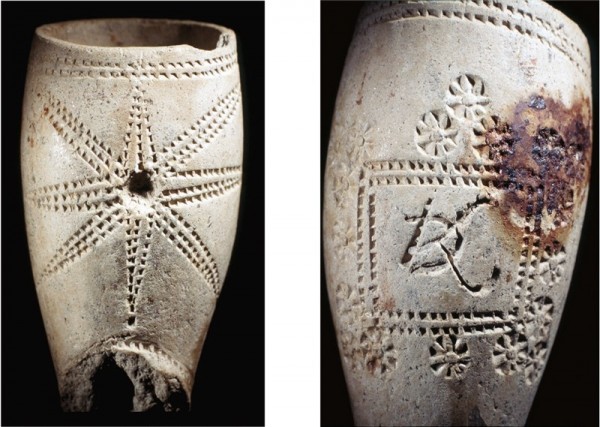

Pipe bowls, recovered from 44CC178, Charles City County, Virginia, ca. 1640. Earthenware. H. 1 5/8". (Courtesy,Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Katherine Ridgway.) Large stamped stars are the most common motif found on local pipes in the lower James River drainage. The type probably originated in Charles City County as a venture of Walter Aston. Workers at Aston’s house created distinctively colonial pipes, molding an Algonquian form adjusted toward European tastes.

Tobacco pipe, Star Maker school, ca. 1640. (Courtesy, Colony of Avalon Foundation; photo, Jim Tuck and Barry Gaulton.) Archaeologists excavated this star bowl, monogrammed “DK,” in Canada from a building associated with Newfoundland’s governor Sir David Kirke. Made in Virginia at the Walter Aston site, the excavation of that production center recovered a bowl fragment with the same “DK” monogram.

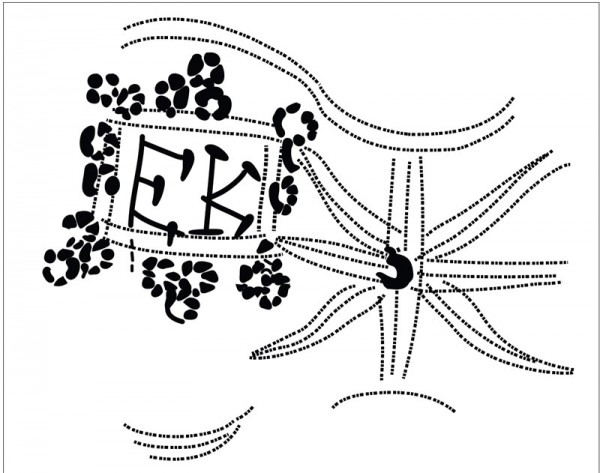

Drawing of a tobacco pipe, recovered from 44CC178, Charles City County, Virginia, ca. 1640–1667. (Artwork by Wynne Patterson.) Martha McCartney searched the records associated with Walter Aston but did not find a possible identification for the “EK” stamped on this pipe. It seems likely that Aston’s star pipes decorated with initials were presents for business associates.

Dish, Harlow, Essex, England, dated 1632. Metropolitan slipware. D. 13 7/16". (Courtesy, Museum of London; site code CEH12, context [105]; photo, Andy Chopping.) European slipwares seem to be the most logical inspiration for stamped decoration filled with white clay, which appears ca. 1620. Dishes such as this may also have served as samplers inspiring colonial pipe makers. Native artists appear to have followed traditional patterns, but colonials new to the craft had to invent their own decorative grammars.

Pipe bowl, recovered from 44WM12, Westmoreland County, Virginia, ca. 1647–1679, Earthenware. H. 1 3/4". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Katherine Ridgway.) This bowl, possibly decorated using a shark’s tooth, shows the stamped horizontal bands often used in Algonquian decoration. It may have been made by a Matchotic working for the colonists living on the Potomac’s Nomini Bay. Overall this is a typical Algonquian elbow pipe, but the carinated rim hints at Siouan or Iroquoian influence.

Pipe bowl, recovered from 44VB48, Virginia Beach, Virginia, ca. 1640–1680. Earthenware. H. 1 15/16". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Katherine Ridgway.) This Running Deer pipe, rotated to show the decoration, matches a pipe found in the Netherlands. Both belong to a group of eight known bowls called “Quadrupeds with ‘Knees,’” which may come from the Delmarva Peninsula. Those eight show variations, but all have bent legs drawn with eight or twelve stamps—the Quadruped motif typically used four straight lines. Two of the Knees group also depict male deer with antlers—the only branched antlers on all of the known Quadruped pipes.

The wife of a “werowance” (chief of Secotan), leaf from a volume (now consisting of 113 leaves of drawings) associated with John White, 1585–1593. Watercolor on papers. (British Museum, SL,5270.5.) This woman “of Secotan” exhibits decorated Algonquian elbow “pipes” on her flesh. The geometrical designs used on Native pipes are probably traditional patterns adapted from weaving, or pottery, or tattoos such as this.

Pipe bowl, recovered from 44JC39, James City County, Virginia, ca. 1650. Earthenware. H. 1 9/16". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Katherine Ridgway.) The pipe shown here looks like a classic bowl from Bénin, but was almost certainly made in Virginia. The form originated with American Indians and appeared in Africa at roughly the same time as tobacco, about 1600. This bowl probably was made a few miles below Jamestown and belongs to an intriguing group of carved pipes generally confined to the James River drainage.

Tobacco pipes, Emanuel Drue, Maryland, ca. 1660–1669. Earthenware. Top: Drue Type B, belly bowl. Center: Drue Type A, angular elbow. Bottom: presentation “Crumm Horn” pipe. (Courtesy, Anne Arundel County, Maryland; photo, Al Luckenbach.) Emanuel Drue made the two classic forms of seventeenth-century English America, the European-style belly bowl, and the Algonquin-style elbow. His elbow pipes include Bookbinder school pipes, and he was the only other maker to produce agated and marbled surfaces. Drue also molded European-style belly bowls in white clay, and made more challenging pipes like the Crumm Horn.

Pipe bowl, found in Schermer, North Holland, ca. 1640–1680. Earthenware. H. 1 3/4". (Photo, Ewout Korpershoek.) Probably made on the Delmarva Peninsula, this is one of only two seventeenth-century American tobacco pipes known to have been found in Europe. One of the Quadrupeds with “Knees,” this was almost certainly decorated by the same person as the Virginia Beach find, illustrated in fig. 17.