In eighteenth-century Britain, the bust as a sculptural form was enjoying a revival. The truncated head and shoulders placed on a plinth was an integral part of the material culture of neoclassicalism, the revival of classical forms in Euro-American design. The British Isles were also in the midst of a religious revival, part of the “awakenings” that were happening across the northern hemisphere, from the Urals to the Alleghenies. While the bust as a representational form reached back to classical history, particularly Greco-Roman design, religious revivals also sought to bring the power of the early Christian church into modern history.

This 1784 bust of eighteenth-century Methodist leader John Wesley embodies both of these simultaneous revivals—classical and religious. John Wesley was one of the most significant religious figures of the eighteenth-century Anglo-American world, overseeing the revivalist movement within the Anglican Church known as Methodism. The bust in neoclassicism didn’t just replicate ancient objects but was also used to elevate modern historical figures of significance, from politicians to poets. By doing so, a visual connection was made between the greatness of the classical past and that of the enlightenment and the age of revolutions. The Staffordshire potteries were crucial in popularizing neo-classical design, including the bust and cameo portrait, in addition to many other potted copies of classical objects, such as the famous Portland Vase. But Staffordshire was also a place where the religious revival thrived, particularly Methodism.

The original sculptor of this bust, Enoch Wood, became one of the most important potters in Staffordshire. His medium was not marble but clay. This humbler, yet local, medium allowed for mass production of decorative objects, and inventive uses of color. Wood made busts and figurines throughout his career. His business, Enoch Wood and Sons, had a particular focus on the American market from the late eighteenth to the middle of the nineteenth centuries, which he supplied with ample potted busts of George Washington, statuettes of Benjamin Franklin, and plates decorated with American naval victories during the War of 1812. Enoch Wood apprenticed as a potter in Josiah Wedgewood’s Bell Works, but soon struck out on his own to great success. When Wood died in 1840, he asked to be buried with three copies of his best work in pottery—one of which was a copy of this bust. He sculpted John Wesley from life in modeling clay in five separate sittings in 1781, when Wesley was the ripe age of 78 and Wood was a young 22. Wesley himself was impressed with Wood’s work and told Wood after he was finished to not touch the piece lest he “mar it.” Those who knew Wesley in this period were astounded by the “perfect likeness” of the bust, the “very faithful copy of nature.” Of all the objects made to represent Wesley, from horse vertebrae busts to oil-on-canvas portraits, Wood’s bust in pottery was immediately recognized as the most accurate; this is ironic given that mass-produced pottery was not known in the period for physiognomic accuracy. Wood tried to copy every detail possible: Wesley’s rumpled robe (from traveling), his loose jowls and prominent wrinkles, even the vein that protruded from his forehead. One admirer of Wesley was so taken by Enoch Wood’s bust that he interrogated Wood about his method and used the potter’s craft as a spontaneous sermon illustration for the role of the Holy Spirit in shaping the human soul. It was fitting that Wesley was so memorably represented in clay not marble, by a sculptor that was as much tradesman as artist, and with all his physical imperfections on display. Wesley was a true believer in enlightenment empiricism but also in encouraging humility in dress, taste and lifestyle. Wesley often preached that the Holy Spirit in the human being was like a treasure hidden in “earthen vessels,” after the words of St. Paul, the body like “what we term earthenware; china, porcelain, and the like.” Much like the empty, hollow center of this bust, Wesley believed the unseen God dwelt within visible human beings, clay temples of the Holy Spirit. Though the body was “weak” and “easily broken in pieces!” pottery remained a fitting metaphor for “a holy Christian.”

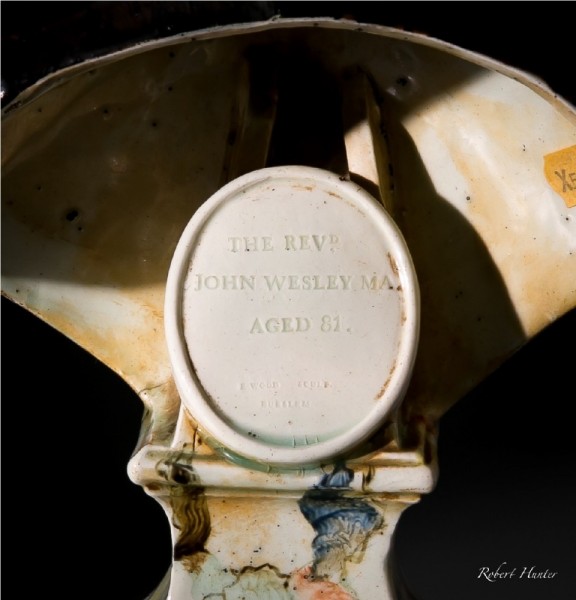

Wood made a cast of his sculpture and started distributing the bust in 1781 in terra cotta to “preachers and friends” who wanted copies for their own homes. This rare copy can be reliably dated to 1784, the second run of busts, probably for the wider market. This was the first time Wood distributed the bust in pearlware. There is evident continuity in molds between the 1781 and 1784 editions, both of which are distinguished by an open back; later editions closed the back and added medallions that often noted Wesley’s death. Wesley is stated as 81 in this copy, his age at the time of manufacture. Subsequent potted busts would lose the close attention to bodily fidelity, and instead became more fanciful representations of Wesley. This bust inaugurated an explosion of ceramics out of Staffordshire known as “Wesleyana,” arguably making Wesley the most depicted person in English ceramics. One twentieth-century guide noted that not only could the busts be seen “in the windows and fanlights over the doors” of Staffordshire cottages, but that “nearly every potter strove to produce mementoes of that great preacher.” The beginning of that trend lies in this bust of the head of the Methodist revivals.

Bibliography

Christopher Allison, “Holy Man, Holy Head: John Wesley’s Busts in the Atlantic World,” Common-Place 15, no. 3 (Spring 2015), http://www.common-place-archives.org/vol-15/no-03/lessons/#.V0M0A77SQ5w.

Malcolm Baker, The Marble Index: Roubiliac and Sculptural Portraiture in Eighteenth-Century Britain (New Haven: Published for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art by Yale University Press, 2014).

Arthur D. Cummings, A Portrait in Pottery (London: Epworth Press, 1962)

George Woolliscroft Rhead and Frederick Alfred Rhead, Staffordshire Pots & Potters (London: Hutchinson and Company, 1906), 265–66.