By the time of Sir William Edward Parry’s second voyage (1821-23) in search of the Northwest Passage, the British public was already fascinated by the Commonwealth’s expansion into “exotic” lands like the arctic. British explorers knew that if they found a way to successfully navigate the treacherous ice flows that make up the Northwest Passage – a direct trade route between Europe and Asia through the Canadian north – they would gain both personal and national wealth. Until Parry’s time, the Northwest Passage had proven elusive for centuries. Still, early expeditions like Parry’s offered new opportunities for visual and textual observations of this landscape. After making it about half way through the Passage, the crew met impenetrable ice and was forced to turn around. During that time, Parry’s co-captain George Francis Lyon drew his impressions of the Canadian north, which were engraved by Edward Finden for Parry’s book Journal of a Second Voyage for the Discovery of a North-West Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific Performed in the Years 1821-22-23, in His Majesty’s Ships Fury and Hecla, Under the Orders of Captain William Edward Parry, R.N., F.R.S., and Commander of the Expedition.

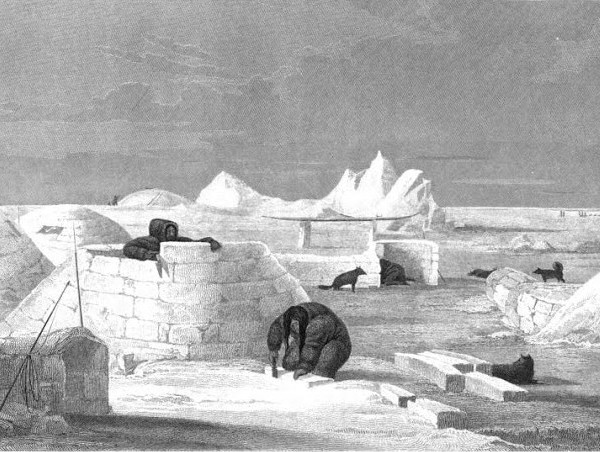

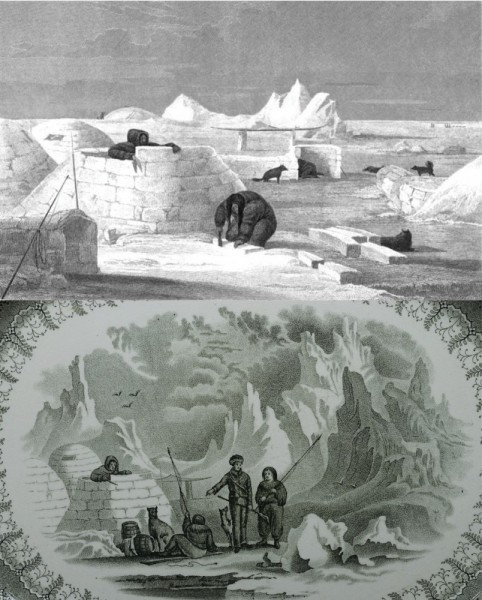

In an effort to take advantage of the widespread popularity of Parry’s journey, an unknown Staffordshire pottery subsequently translated Lyon’s imagery onto transfer printed ceramics for the “Arctic Scenery” table service [fig. 1, 2]. The central image on the circa 1835 Arctic Scenery platter in Chipstone’s collection is adapted from the print “Esquimaux [Inuit] Building a Snow Hut [Igloo]” [fig. 3, 4]. Associations between this platter and “Esquimaux Building a Snow Hut” are clear in the similar appearance of an Inuit person in an igloo working on its construction, the two igloos to the left that feature a prominent ice window, the harpoons, and the thin pointed kayak characteristic of the Caribou, Copper, and Netsilik Central Canadian Inuit nations for their practice of hunting swimming Caribou (a scene depicted in the following plate in Parry’s book). The Staffordshire potter then added a white man with a gun, perhaps meant to depict Parry or one of his crewmen in dialogue with an Inuit person. What’s more, these Inuit figures were given the same facial features as the British explorers and were drawn wearing oddly draped and inappropriately thin clothing.

These figures are also accompanied by dogs closer in appearance to Dobermans than their northern sledge dog counterparts seen in Finden's print. Even the snowy landscape that surrounds these figures is strangely rendered into high rounded peaks, transforming the Northern landscape into a surreal British dreamscape that blends into the clouds. In effect, this Staffordshire platter is a British interpretation of a British interpretation of the central Canadian north, thematically distorting reality to allude to the foreignness of the Arctic Scene in ways that visually colonize the Inuit and their landscape.

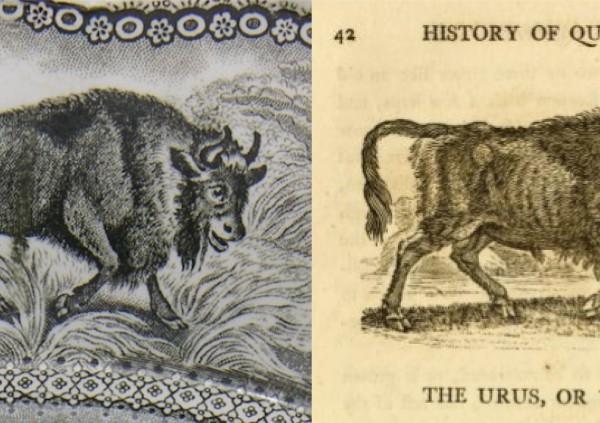

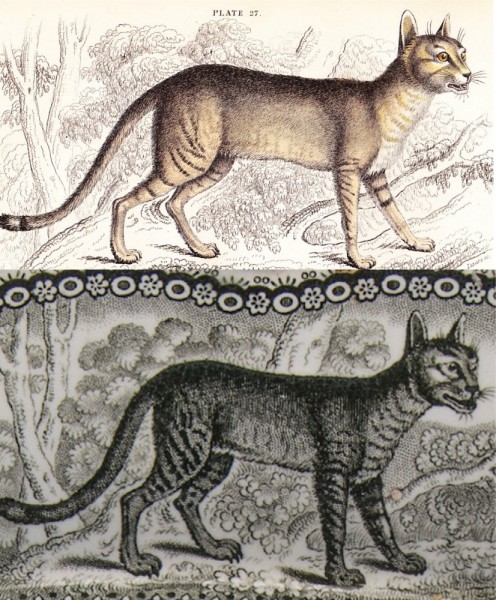

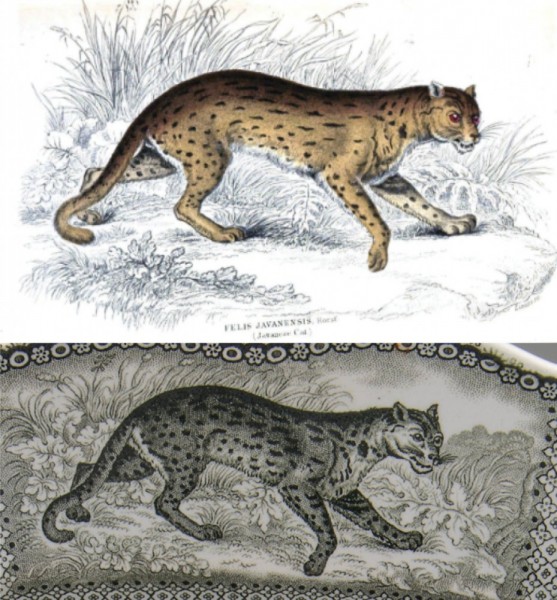

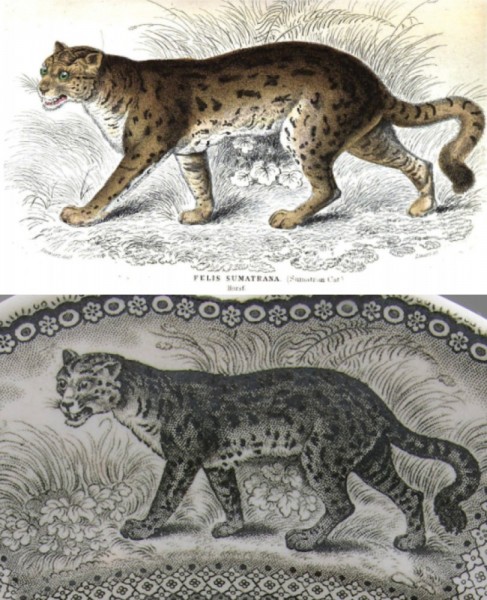

But what of the incongruous inclusion of tropical animals and flowers around the edge of the platter? On one hand, it evidences the widespread popularity of early nineteenth century natural history books, most notably those from which the illustrations were borrowed [fig. 5-8]. William Jardine’s Naturalist’s Library (1837) and T. Bewick’s A General History of Quadrupeds (1790) capitalized on the British public’s desire for “exotic” landscapes, animals, and people – a desire that this Staffordshire pottery attempted to capitalize on, as well.

Yet both Jardine’s and Bewick’s volumes also feature images of northern animals such as seals and whales that would have been more appropriate for this table service. It is then possible that the pottery’s engraver or illustrator employed these images to advance “the sun never sets on the British empire” argument, which posits that the British Empire was so expansive that the sun would always shine on British territory. Notably, none of these animals were from British colonized areas at the time of this platter's creation, indicating a confident assertion that all warm climate regions would or could soon be British, and a simultaneous subversion of that assertion.

While in its own time this blurring of geographic boundaries may have been a marketing or imperialist move, today it stands as an increasingly possible and poignant reality, an eerily accurate commentary on climate change in the twenty-first century. The tropical Arctic Scenery imagery could well come to fruition in the decades to come as our climate warms and the ice zones melt.

Once impenetrable and unpredictable ice flows that held Parry and so many others back are today melting and breaking apart. The Northwest Passage will soon be open, and the ramifications for ecosystems are dire. As Inuit activist and author Sheila Watt-Cloutier argues, when the ice melts and cracks, so too will the Inuit identity and community, which rely on traditions and livelihoods that in turn rely on this landscape. As Watt-Cloutier has flagged time and again, these threats of lost cultural identity have today led in some Inuit communities to shockingly high suicide rates, a symptom of what she terms “climate trauma.” When viewed through a contemporary lens, this “curious” nineteenth-century Staffordshire platter takes on new and troubling meaning, drawing attention to contemporary issues that demand resolution and action.

For a map showing the geography of the images used on Chipstone's Arctic Scenery platter, click here.

For more on Central Canadian Inuit, the kayaks they make and use, and their hunting traditions, click here.

To see more of Edward Finden's engravings of Sir William Edward Parry's second voyage, click here.