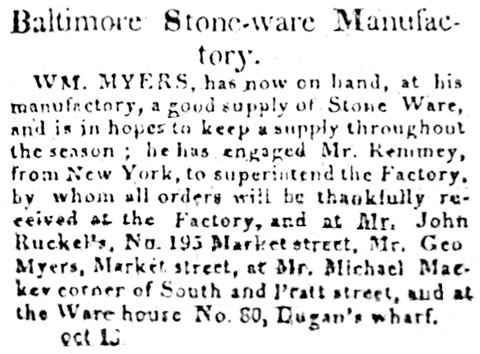

Newspaper advertisement for china merchant William Myers’s Baltimore Stoneware Manufactory, October 13, 1812. This is the first known reference to Henry Remmey in Baltimore.

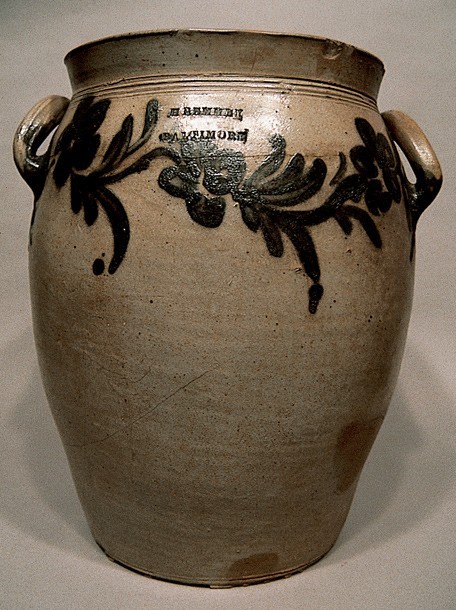

Henry Remmey’s Baltimore maker’s mark. (All photos, Luke Zipp.) Since Remmey never owned his own stoneware pottery in Baltimore, he probably produced stoneware bearing this mark at the Baltimore Stoneware Manufactory under Jacob Myers, 1818–1821, although an earlier date for this stoneware is possible.

Mark used on stoneware made at the Baltimore Stoneware Manufactory under Henry Myers’s ownership. Henry Remmey superintended the manufactory from 1821 to 1829.

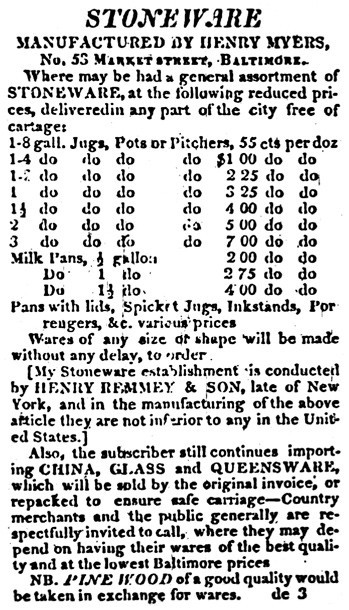

Newspaper advertisement and price list for merchant Henry Myers’s stoneware manufactory, July 3, 1823. Not only does this advertisement serve as proof that Henry Remmey and Henry Remmey Jr. manufactured “H. MYERS” stoneware, but it also clarifies the types of stoneware they produced for Myers.

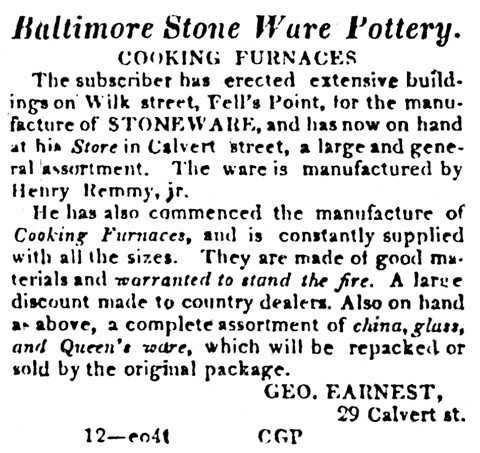

Newspaper advertisement announcing the opening of merchant George Earnest’s stoneware manufactory, August 14, 1824. According to this ad, Earnest secured Henry Remmey Jr. as the superintendent of his new pottery.

Jar, Henry Remmey, Baltimore, 1812–1821. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15". (Private collection.) Impressed “H. REMMEY / BALTIMORE,” this storage jar has a form identical to examples made in Manhattan in the early nineteenth century. The cobalt decoration is typical of Remmey’s earlier Baltimore work.

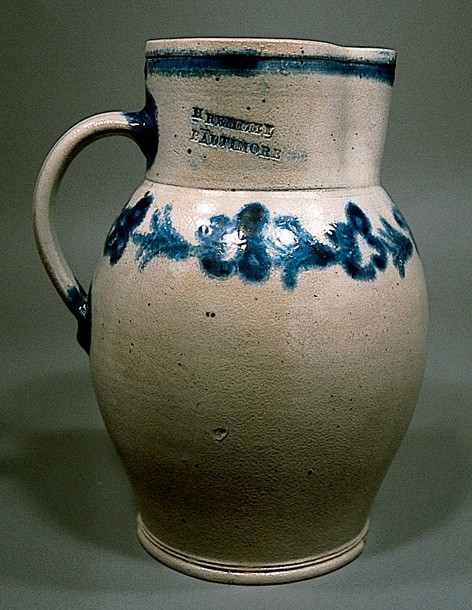

Pitcher, Henry Remmey, Baltimore, 1812–1821. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 11Ω". (Private collection.) The pitcher’s decorative motif, vibrant cobalt, and pure gray clay are typical of Remmey’s Baltimore stoneware. The impressed “H. REMMEY / bALTIMORE” mark is illustrated in fig. 2

Wine cooler, Baltimore, ca. 1815. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 11". (Private collection.) Although unsigned, this keg was almost certainly made by Henry Remmey in Baltimore. The keg form is rarely seen in Baltimore stoneware but is not uncommon in Manhattan stoneware.

Pitcher, Henry Remmey, Baltimore, 1812–1821. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 11". (Private collection.) Impressed “H. REMMEY / BALTIMORE,” this pitcher, with its incised bird decoration, displays Remmey’s command of incising. He included fine details of the birds and flowering trees, and washed the decoration with vibrant cobalt confined almost entirely within the incised lines.

Ink bottle, Henry Remmey, Baltimore, 1812–1821. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 5". (Private collection.) The type used in the “H. REMMEY” mark on this bottle is the same as that used on the “H. REMMEY / BALTIMORE” stamp. This comparison, combined with the clay color of the bottle, confirms a Baltimore attribution.

Cooler, Henry Myers, Baltimore, 1821–1829. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 16". (Courtesy, Olde Hope Antiques, Inc.) Impressed “H. MYERS,” this incised bird-decorated vessel is referred to as a “Spicket Jug” in Myers’s price lists. Certainly made by Remmey while working for Myers, the close link between the decoration on this piece and “H. REMMEY / BALTIMORE” stoneware suggests that this cooler was probably made by Remmey toward the beginning of Henry Myers’s tenure. The form of the bird as well as the quality of incising are similar to the pitcher illustrated in fig. 9. A fine flowering-vine decoration on the reverse of the cooler matches Remmey’s early decorative motifs.

Jars, Henry Myers, Baltimore, 1821–1829. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15". (Private collection.) These impressed “H. MYERS” jars were manufactured while Henry Remmey worked for Myers and reflect Remmey’s shift toward mass production. The forms are simpler than those seen in his earlier wares and the decoration is less finely executed

Pitchers, Henry Myers, Baltimore, 1821–1829. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 10 1/2". (Private collection.) Both of these pitchers are impressed “H. MYERS” and reflect Remmey’s standardization of this form under Henry Myers. The pitcher on the left displays Remmey’s standard “H. MYERS” brushed cobalt decoration. The decoration on the pitcher at right shows up on Remmey Philadelphia stoneware and possibly was made by Henry Remmey Jr

Jug, Henry Myers, Baltimore, 1821–1829. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15". (Private collection.) Although undecorated, this impressed “H. MYERS” jug is elaborate for its form. An ovoid shape and incising at the base and neck add to the visual appeal of this vessel.

Milk pan, Henry Myers, Baltimore, 1821–1829. Salt-glazed stoneware. D. 9 3/4". (Private collection.) This milk pan, impressed “H. MYERS,” bears a variation of Remmey’s standard decoration.

Churn, Henry Myers, Baltimore, 1821–1829. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12 1/2". (Private collection.) Impressed “H. MYERS.” Although not a standard production item at the Henry Myers pottery, stoneware churns are not unusual in Baltimore stoneware.

Flowerpot, Baltimore, ca. 1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 7". (Private collection.) Excavated in Baltimore City (part of the bird at left has been restored), this incised bird-decorated flowerpot was almost certainly made by Henry Remmey Jr. in Baltimore. While its clay and cobalt color substantiate its Baltimore origin, the flowerpot’s incising is very similar to incising found on Remmey Jr.’s Philadelphia stoneware.

Reverse of the flowerpot illustrated in fig. 17.

The Remmeys stand in American decorative arts history as arguably the most influential family of stoneware potters. Although the history of their potteries in Manhattan and Philadelphia has been sufficiently fleshed out, their potting activity in Baltimore remains largely undocumented. Based on the scant mention of the name Remmey in Baltimore business directories and the rarity of extant examples of stoneware signed "H. REMMEY / BALTIMORE," it has long been assumed that Henry Remmey Jr. briefly operated a pottery in Baltimore but returned to his father's successful Philadelphia manufactory when his Baltimore experiment failed. As a result, his tenure in Baltimore exists as a footnote and a failure in the history of the Remmeys. However, new research has revealed that both Henry Remmey Sr. and Henry Remmey Jr. worked in Baltimore, and their impact there was, in fact, far greater than previously thought.[1]

Remmey Sr. was born around 1770 and inherited an American stoneware potting tradition handed down by his grandfather, John Remmey I, who arrived in New York in 1735. John's family had been practicing in France and Germany for centuries when he set up his shop in New York, and the stoneware that he and his descendants produced in Manhattan was recognized as the finest in the country. In 1793 Henry took over operation of the pottery with his brother, John Remmey III, but his association with the shop did not last long; he left his brother in 1796 and began a series of independent business ventures.[2]

In 1806, however, Henry Remmey's fortunes in New York changed. Louis Zukofsky, in his Depression-era radio script entitled "Remmey and Crolius Stoneware," describes the dramatic turn of events:

In 1803, [Henry Remmey] had been appointed to the position of Superintendent of City Scavengers — street cleaners we call them today — and when three [years] later the office was abolished, he was found guilty of appropriating city funds. He begged, "on account of the distressed state of his family," to be excused from repaying the money which he had collected during his term of office. But the Council refused.[3]

Unable to comply with the council's ruling, Remmey took his family and fled New York City.[4]

Henry Remmey arrived in Baltimore in the summer or early fall of 1812.[5] Although the colonies had won their independence, the emerging United States remained financially bound to Britain and American consumers continued to crave British products. It was not until events leading up to the War of 1812 halted trade relations with England that America began to respect its homegrown artisans for their skills, and in the realm of American stoneware no potters were respected more than those from New York City.

In June 1812 William Myers, a Baltimore china merchant, decided to manufacture his own pottery when he "purchased of Mr. James Johnson, his well known Manufactory of stone ware" on Bond Street, north of Pitt Street, and retained Johnson to superintend the operation. Initially Myers supplemented his inventory with superior stone- and earthenware produced in Hartford, Connecticut, while he made plans to expand the manufactory. He added new materials and workers and renamed the business "Baltimore Stone Ware Manufactory."[6] But his chief aim was to produce stoneware of the highest possible quality, and for that he hired a new manager. On October 13, 1812, he announced that he had "engaged Mr. [Henry] Remmey, from New York, to superintend the Factory . . ." (fig. 1).[7]

The arrangement between Myers and Remmey benefited both men. With Remmey's help Myers anticipated manufacturing stoneware that rivaled the best New York products. Myers's mention that his new pottery superintendent was from New York surely carried implications of quality to Baltimore consumers. As an impoverished fugitive, Henry Remmey was undoubtedly delighted to manage a large pottery without having to own it and to enjoy status as a master craftsman in a city that had a dearth of them. Moreover, Myers seems to have compensated Remmey well for his skill; in addition to a fair daily wage, Remmey eventually was given a house to live in rent-free.[8]

Remmey Sr.'s arrival in 1812 represents a major turning point in Baltimore's stoneware products. Baltimore merchants relished the opportunity to offer stoneware from Manhattan. Myers clearly knew the value of the Remmey family name, as he referred to it for more than three straight months in Baltimore newspapers. As manager of the manufactory, Remmey Sr. not only produced a large amount of high-quality stoneware for Myers to sell, he also ensured superior products by the workers under his charge. And his position as superintendent gave him added status, which led to the improvement of the Baltimore potting school in general.[9]

The documentary evidence for Remmey Sr.'s early years in Baltimore remains sparse. He does not appear in the Baltimore business directories until 1817, he does not appear in Baltimore land records as a purchaser or lessee of property, and he is absent from Baltimore court records. Presumably this lack of information is related to his problems in New York; as a fugitive with known financial problems, he would not have wanted to make his whereabouts widely known, and he did not — probably could not — purchase property. As a result, little about his activity for much of the 1810s is known.

We do know that he worked at the Baltimore Stoneware Manufactory between October 13, 1812, and January 20, 1813, based on Myers's newspaper ads. And he was definitely potting at the Baltimore Stoneware Manufactory with his son Remmey Jr. in April 1818, because an advertisement placed that month by Jacob Myers (presumably William's brother), who owned the manufactory by then, states that Myers's "Stone Ware is manufactured by Henry Remmey & Son, of New-York, and is inferior to none in the United States, they being regularly brought up to the business...."[10] Between 1815 and 1818, however, there is virtually no evidence concerning the whereabouts of Remmey Sr., though it is quite possible he never left the Baltimore Stoneware Manufactory despite changes in ownership.

By June 1815 William Myers wanted to expand his potting establishment to keep up with demand. He placed a newspaper advertisement that announced, "Two or more potters are wanted at the stoneware manufactory as journeymen."[11] He also sought a partner who could help finance the expansion. (Remmey Sr., of course, would not have qualified.) That month, potter Elisha Parr came to the manufactory and became William Myers's business partner.

Elisha Parr remained a partner in the Baltimore Stoneware Manufactory until March 1818, when he opened his own stone- and earthenware pottery a couple of blocks west, on Pitt Street. In the intervening three years, William Myers left the stoneware business, selling out to Jacob Myers. When Parr left, Jacob attempted to sell the business but changed his mind, instead advertising in April of that year that he "continues manufacturing Stone Ware, at his factory, upper end of Pitt street, old town." He refers to "Henry Remmey & Son, of New-York" in the ad, which, along with other evidence discussed below, supports a contention that extant stoneware impressed "H. REMMEY / BALTIMORE" (see, for example, fig. 2) was manufactured at the Baltimore Stoneware Manufactory under the ownership of Jacob Myers.[12]

Jacob Myers owned the manufactory until November 1, 1821, when, at age sixty-three, he passed the business to his son, Henry.[13] Under Henry's ownership the manufactory produced vessels impressed "H. MYERS" (fig. 3); a significant number of them survive.

In his first year of business, Henry Myers advertised his stoneware price list in the Baltimore newspapers (fig. 4) and, like his father before him, notified the public, "My Stoneware establishment is conducted by HENRY REMMEY & SON, late of New York, and in the manufacturing of the above article they are not inferior to any in the United States."[14] That same year the Baltimore business directory lists Remmey as working at a stoneware factory on the northwest corner of Bond and Pitt Streets (the Myers pottery). Other directory listings place Remmey Sr. continuously at the Baltimore Stoneware Manufactory through 1829, the year he probably left the city altogether.[15]

Since Remmey Sr. worked for Henry Myers for approximately seven years, a large portion of the extant "H. MYERS" pieces were probably manufactured by Remmey Sr. himself, or at least under his direct supervision. Since extant stoneware from New York and Baltimore signed by Remmey Sr. is rare, his most significant representation in the American stoneware record is probably vessels marked "H. MYERS." Myers stoneware reflects a combination of skill and efficient production uncommon for stoneware in 1820s Baltimore.[16] Remmey Sr. ended his forty-year career working at Henry Myers's pottery in 1829, when he retired to live in Philadelphia with Remmey Jr., who two years earlier had established a pottery there.

Surprisingly little documentary evidence exists about Remmey Sr.'s Baltimore activities. Earlier assumptions about the Remmeys are based on an entry in an 1824 business directory that lists Remmey Jr. as living at Pitt and Bond Streets and working at a stoneware factory on Wilk Street. Since Remmey Sr. is not mentioned, scholars have interpreted this record to mean that only Remmey Jr. worked in Baltimore. Furthermore, it had been assumed that Remmey Jr. owned the pottery. Remmey Jr.'s purchase, along with Enoch Burnett, of Branch Green's Philadelphia pottery in May 1827, just three years after the beginning of the Wilk Street pottery, led many to assume Remmey Jr. had failed at his first attempt at pottery ownership.[17]

In actuality, Remmey Jr. worked with his father at the Baltimore Stoneware Manufactory until 1824, when he was hired away from Myers to be the main potter for another merchant-owned operation. George Earnest, a Baltimore china merchant, followed in the footsteps of the Myers family by attempting to manufacture his own stoneware. His initial announcement of his pottery (fig. 5) stated that he had "erected extensive buildings . . . for the manufacture of STONEWARE." And, as a testament to the quality of stoneware produced by his new establishment, Earnest declared, "The ware is manufactured by Henry Remmy, Jr."[18]

Since Earnest, who catered to southern markets, infrequently advertised his pottery establishment in local publications, this manufactory has been recognized for its short-lived association with Remmey Jr. The manufactory, which eventually passed to Earnest's heirs, did last more than thirty years, which could be credited to Remmey Jr.'s early management. Certainly, when Remmey Jr. moved to Philadelphia in 1827, the stoneware manufactory he purchased would dominate the city's potting industry into the twentieth century.

The Remmeys' Baltimore Wares

Remmey Baltimore stoneware is well thrown and evenly fired. Most is decorated with cobalt oxide. Enough examples of signed or definitively attributable Remmey Baltimore stoneware exist to qualitatively judge the potters' abilities, and these pieces reveal a mastery of forming, decorating, and firing. A few surviving vessels bear ornate incised decoration attributable to Remmey Sr.'s skill. All of the stoneware discussed in this section was made by Remmey Sr. (or under his supervision), with the exception of a flowerpot that is attributed to his son.

The stoneware impressed "H. REMMEY / BALTIMORE" that Remmey Sr. produced during part or all of the period 1812-1821 more clearly resembles products in the Manhattan style. His Baltimore pots look nearly identical to early Manhattan pots, with loop handles, high-neck collars, and incised lines below the rim. He certainly produced the stoneware bearing his name at the Baltimore Stoneware Manufactory, and there is no documentary evidence linking him to any other manufactory (and we know the Remmeys did not own a shop of their own in Baltimore). Furthermore, the same one-and-one-half-gallon capacity mark found on a marked Remmey Baltimore pitcher is found on "H. MYERS" vessels as well, further suggesting that these articles were made at the same shop.[19]

It is unusual for a pottery owner to encourage an employee to mark the stoneware he produced with his own name, but Remmey Sr. and Remmey Jr. were unusually skilled potters and had particular eminence in the context of Baltimore pottery. While it is possible that Remmey Sr. produced stoneware marked with his name at the Baltimore Stoneware Manufactory under both William and Jacob Myers, it is more likely that the "H. REMMEY / BALTIMORE" stoneware was produced between 1818 and 1821, when Jacob Myers was the sole owner of the manufactory. No other Baltimore stoneware producer used an impressed maker's mark until after the War of 1812, when resumed trade with Britain spurred local craftsmen to market their products, and the Myers family probably held to this pattern as well.[20]

While not representative of the evenly fired clay and vibrant cobalt decoration of Remmey Baltimore stoneware, a large, four-gallon stoneware pot marked "H. REMMEY / BALTIMORE" (fig. 6) does demonstrate the Manhattan form Remmey Sr. used in his earlier pots.[21]A tall collar, a series of incised lines below the collar and at the base, loop handles, and ovoid shape typify early-nineteenth-century production in New York City by the Remmeys, Croliuses, and others. Remmey Sr. decorated this pot with the same motif (horizontal vine with four-petal flowers) that he used on his "H. REMMEY / BALTIMORE" stoneware.

Two vessels attributed to Henry Remmey, Baltimore — a marked one-and-one-half-gallon pitcher (fig. 7) and a wine keg (fig. 8) — are decorated with variations of this floral motif. Both exhibit the evenly fired gray clay and bright cobalt-oxide slip characteristic of Remmey Sr.'s Baltimore work. The unsigned wine cooler is easily attributed based on these attributes and its Baltimore-area provenance. The cooler or keg form, common in Manhattan, is virtually unknown to stoneware production south of Pennsylvania. The extravagant use of cobalt slip and the word "Wine" in script are features more typical of Remmey Sr. than any other Baltimore potter at the time.[22]

Baltimore pitchers marked by Remmey do not exhibit many common characteristics. Although they all are fashioned with ovoid bodies with footed bases and ribbed handles, the collars vary sharply in style. The collar on the pitcher in figure 7 seems fairly typical of most nineteenth-century examples, with a short spout and single incised line at the top. A signed "H. REMMEY / BALTIMORE" pitcher with incised decoration in the Henry Ford Museum, Dearborn, Michigan (acc. no. 57.65.21) has a collar with an extremely elongated spout, reminiscent of period silver forms. The form of a one-gallon pitcher signed "H. REMMEY / BALTIMORE" and with incised bird decoration (fig. 9) is not nearly as exaggerated as the pitcher in figure 7. The decoration around the collar is blurred but resembles the potter's characteristic vine-and-flower decoration. Remmey Sr. used a fine implement to incise the details into the clay — the wings, feathers, and eyes of the birds, and even the veins of the leaves. He carefully applied thick cobalt slip, keeping it within the incised decorations[23]

Highly decorative vessels are not all that bear Remmey's mark, however (a jug signed by him only uses cobalt decoration to highlight his name). And the diversity of his forms is indicated by a stoneware ink bottle (fig. 10). Although not listed in any of Myers's price lists, the ink bottle form was probably one of Remmey's regular production items, because another, virtually identical bottle exists. However, neither is decorated with the cobalt oxide or heavy salt glaze characteristic of Remmey's Baltimore wares.[24]

The "H. MYERS" stoneware example most similar to Remmey's signed Baltimore work is a four-gallon water cooler with incised bird decoration (fig. 11). An uncommon form for early Baltimore, this water cooler is related to the "Spicket Jugs" listed on Henry Myers's 1822-1823 stoneware price list. Remmey Sr. decorated the reverse of this cooler with his typical vine-and-floral motif. The overall form — ovoid shape and footed base — resembles that of "H. REMMEY / BALTIMORE" pitchers. The clay color, even salt glaze, and vibrant cobalt-oxide decoration are all typical of Remmey Sr.'s Baltimore work. The incised grouse-on-branches decoration covering the front of the cooler highlights Remmey's command of the incising technique.[25] The form and decorative detail of this bird closely match the birds on the pitcher illustrated in figure 9. Given the similarities between this water cooler and the piece marked "H. REMMEY / BALTIMORE," the cooler was probably manufactured by Remmey Sr. at the Baltimore Stoneware Manufactory shortly after Henry Myers took over ownership from his father.

Other extant "H. MYERS" stoneware articles have Remmey attributes. In the seven years that Remmey Sr. potted for Henry Myers, the form and decoration of his vessels changed, perhaps due a greater emphasis on mass production at the pottery.[26] Delicate freehand details, including open flower petals and berries, are replaced by broader, rapidly applied brushstrokes, resulting in a thicker band of decoration. But Remmey Sr.'s decoration of Myers's stoneware retains similarities to his earlier decorations, continuing, for example, the motif of flowers rising and falling from a central horizontal vine that surrounds the entire vessel.

Remmey Sr. also altered the forms of his "H. MYERS" stoneware to promote mass production. Instead of loop handles, all Myers pots are adorned with smaller, tablike handles. Instead of high-neck collars, many Myers pots have short rims. Nevertheless, the overall decorative appeal of Remmey Sr.'s stoneware from this manufactory remains, and artistic decoration, vibrant blue, evenly fired gray clay, and ovoid forms characterize his late pieces. For example, in figure 12 the pot on the left, which holds three gallons,[27] has a high-neck collar similar to those on Remmey Sr.'s earlier Baltimore pots and early Manhattan stoneware, and he incised lines at the base of both of these pots, as he had in his early days in Baltimore. The decorations on both pots is very similar, with horizontal flowering garlands surrounding the body. However, these vessels are adorned with tab ears, and Remmey left out the series of incised lines beneath the collar. To create the flower heads, he made a series of thick brushstrokes instead of outlining four petals, as he had on his "H. REMMEY / BALTIMORE" stoneware.

Remmey's "H. MYERS" stoneware pitchers are much more consistent in form than his early examples. A side-by-side comparison of two signed "H. MYERS" pitchers (fig. 13), a one-gallon and a half-gallon,[28] reveals this standardization. Both have slightly ovoid bodies, incised lines at their bases, vertical collars with incised lines bisecting each collar, and slightly drooping pouring spouts. (The handle on the half-gallon pitcher, at right, is a modern restoration, so the variation in the forms of these handles probably did not exist when these pitchers were manufactured.) The decoration on the one-gallon pitcher, at left, is an example of Remmey Sr.'s standard stoneware decoration under Henry Myers. The decoration on the half-gallon pitcher, at right, appears on Remmey Philadelphia stoneware, suggesting that it may have been decorated by Remmey Jr.

The few extant signed Myers jugs do not display much deviation from the earlier signed Remmey jug form. A two-gallon "H. MYERS" jug (fig. 14) illustrates what was most likely the typical jug form Remmey used under Henry Myers.[29] Incised lines accentuate a foot at the jug's base, and a series of incised lines cover the jug's neck, supporting a wider mouth. There is no cobalt decoration.

In addition to jugs, pots, and pitchers ranging in capacity from one pint to three gallons, Remmey produced other unusual forms, according to Myers's 1822-1823 price list. He made "spicket jugs," inkstands, porringers, pans with lids, and milk pans. A surviving "H. MYERS" one-and-one-halfgallon milk pan (fig. 15) bears his standard decoration.[30]

Remmey also produced stoneware forms not advertised by Myers. A one-and-one-half-gallon churn (fig. 16), impressed "H. MYERS" and decorated with Remmey's vine-and-flower motif, survives. Although this form is not mentioned on the manufactory's price list, the presence of other Baltimore stoneware churns from roughly the same period reveals the popularity of the form in Baltimore. And the mention at the bottom of the price list that "Wares of any size or shape will be made without any delay, to order," indicates that Remmey made stoneware forms that were not typical production items.[31]

Judging by Philadelphia stoneware bearing his name, Remmey Jr. unquestionably had great skill in forming, decorating, and firing stoneware. However, while we know that stoneware from Philadelphia signed "Henry Remmey" can only be the work of Remmey Jr., Baltimore vessels signed "H. REMMEY / BALTIMORE" and "H. MYERS" were made by or under the supervision of his father. Remmey Jr. could have made some of the vessels discussed herein, but his influence at the Baltimore Stoneware Manufactory was secondary to his father's and his presence at the Myers pottery did not last as long. Unfortunately, no known Baltimore stoneware exists that was personally signed by him, nor is there surviving stoneware signed George Earnest, whose pottery Remmey Jr. superintended. Therefore, any discussion of Remmey Jr.'s Baltimore stoneware would rely heavily on speculation.

One piece, a heavily incised stoneware flowerpot with bird-and-flower decoration (fig. 17), was almost certainly made by Remmey Jr. while in Baltimore, however. Although unsigned, the flowerpot's Baltimore attribution is definite, given its clay and cobalt color and the fact that it was excavated in an early-nineteenth-century Baltimore privy. And of all potters in Baltimore at that time, only the Remmeys could have achieved the high quality of the incised decoration. Remmey Jr. would have made the flowerpot either at the Baltimore Stoneware Manufactory or at George Earnest's Wilk Street manufactory.[32] The deeply incised decoration is good, and, although Henry Remmey Jr.'s potting abilities were not equal to those of his father, they unquestionably were superior to the rest of his Baltimore peers.

Before Henry Remmey Sr. arrived in Baltimore in 1812, the quality of stoneware production in the city was such that William Myers chose to import from Hartford rather than sell local wares in his shop. But Remmey Sr. changed the whole dynamic of Baltimore stoneware, producing pottery for the Baltimore Stoneware Manufactory that was without parallel. The expertly formed, decorated, and fired Remmey Baltimore stoneware adequately testifies that Henry Myers was no mere braggart when he stated that the stoneware potters Henry Remmey & Son, late of New York, were "not inferior to any in the United States."[33]

W. Oakley Raymond expresses the common belief about the Remmeys in Baltimore: "Evidence drawn from the Baltimore directories makes it certain that Henry Remmey, founder of the Philadelphia works, sought to command two profitable markets by placing his son Henry Harrison [Henry Remmey Jr.] in charge of a Baltimore branch. . . . Whatever the father's purpose in entering the Baltimore market, he either found, or presently developed, plenty of local competition. . . . This may help to explain why by September 25, 1835 . . . we find [Henry Remmey Jr.] in Philadelphia." W. Oakley Raymond, "Remmey Family: American Potters, Part II," Antiques 32 (1937), quoted in Diana Stradling and J. Garrison Stradling, The Art of the Potter (New York: Main Street/Universe Books, 1977), p. 116.

Stradling and Stradling, Art of the Potter, pp. 114-16.

Louis Zukofsky, A Useful Art: Essays and Radio Scripts on American Design (Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 2003), p. 197. This script was penned for the Works Progress Administration.

Stradling and Stradling, Art of the Potter, p. 116.

Henry Remmey Jr., who was by then eighteen years old, almost certainly accompanied his father to Baltimore. He potted with him from 1812 until he gained enough experience to be recognized as a highly skilled potter in his own right.

American & Commercial Daily Advertiser, July 4, 1812, p. 1; American, July 3, 1812, p. 4.

American, October 15, 1812, p. 2.

The evidence that supports a rent-free arrangement is persuasive. Remmey does not appear in Maryland land records as leasing or purchasing property in Baltimore. In 1817-1818 he is listed as living at the north end of Happy Alley, which was near the Baltimore Stoneware Manufactory (although it was also close to other stoneware potteries, notably the Pitt and Green Street pottery of Morgan and Amoss, and the Eden Street pottery of Parr and Burland). The records of 1822-1823, 1824, and 1829 show Remmey living on Bond Street. From an 1838 newspaper listing for the trustee's sale of the property of Henry Myers (Jacob Myers's son) we know that the Myers family owned on Bond Street "a small dwelling . . . heretofore occupied by the person who has conducted [the] pottery." This dwelling presumably is where Remmey lived in the 1820s. The Baltimore Directory for 1817-18 (Baltimore, Md.: Printed by James Kennedy, 1817), p. 157; The Baltimore Directory for 1822-23 (Baltimore, Md.: Printed by R. J. Matchett, 1822), p. 231; Matchett's Baltimore Directory for 1824 (Baltimore, Md.: Printed by R. J. Matchett, 1824), p. 253; Matchett's Baltimore Directory for 1829 (Baltimore, Md.: Printed by R. J. Matchett, 1829), p. 265; American, September 11, 1838, p. 3.

It is interesting to note, however, that he never took a formal apprentice in Baltimore. Information concerning Baltimore stoneware prior to 1812 is sketchy, but the fact that William Myers needed to import Hartford stoneware in 1812 (American, July 4, 1812, p. 1.) is a strong indication that Baltimore-manufactured stoneware was of inferior quality. A stoneware pitcher excavated from a Baltimore privy dating to the early 1800s is probably an example of the type of stoneware produced in Baltimore before Remmey's arrival. Its form is not much different from the form of Remmey's pitchers, but it is decorated with only a small amount of cobalt. Also, it has a very light salt glaze and its clay has an uneven, blotchy appearance. Known examples of Baltimore stoneware dating after Remmey's arrival are of much higher quality, especially in terms of decoration and glaze.

Baltimore Directory for 1817-18, pp. 129, 146, 157 (emphasis added); Supplement to the American, April 28, 1818, p. 1.

American, June 8, 1815, p. 4.

American, December 23, 1815, p. 4; Supplement to the American, March 27, 1816, p. 1; American, March 7, 1818, p. 4; American, July 2, 1818, p. 4; Supplement to the American, April 28, 1818, p. 1.

American, September 25, 1822, p. 2. This issue of the American lists the obituary for Jacob Myers, who died less than a year after passing his business to Henry Myers.

American, July 3, 1823, p. 1.

Baltimore Directory for 1822-23, p. 231; Matchett's Baltimore Directory for 1824, p. 253; Matchett's Baltimore Directory for 1829, p. 265. It is clear that Remmey Sr. was still working for Myers in 1824, because a directory listing places his son, Henry Harrison Remmey (Henry Remmey Jr.), at another pottery at the time. The directory gives Remmey Jr.'s dwelling at the corner of Pitt and Bond; undoubtedly he lived there with his father, since we know that Henry Myers owned a house adjacent to the pottery for the use of the manufactory's superintendent (see n. 8). In 1829 the business directory still lists Remmey Sr.'s residence as being at Pitt and Bond.

The forms, standardized decorations, and even firing exhibited in "H. MYERS" stoneware are more typical of stoneware produced circa 1840 and later in Baltimore and Virginia.

Matchett's Baltimore Directory for 1824, p. 253; Philadelphia County Recorder of Deeds, 1827, vol. gwr 17, p. 250.

American, August 14, 1824, p. 1.

Capacity-mark stamps were part of the tools of a shop, and pieces bearing identical capacity marks usually were manufactured at the same shop.

David Parr began marking his stoneware no earlier than 1815, Elisha Parr marked his no earlier than 1818, and William Morgan began marking his stoneware with incised signatures circa 1819.

This pot is an example of the largest size stoneware on Myers's price lists. In 1815 it retailed for $1.25. American, October 23, 1815, p. 4.

In 1815 a one-and-one-half-gallon stoneware pitcher retailed at Myers's shop for $.62 1/2. Kegs, water coolers, and similar forms do not appear on Baltimore price lists for the 1810s. Ibid.

This pitcher is the only signed "H. REMMEY / BALTIMORE" vessel with a different maker's mark. While the mark on other Remmey pieces consists of movable letters arranged to form the words, the mark on this pitcher is created from two stamps of permanently affixed letters, one for "H. REMMEY" and one for "BALTIMORE."