Tea table attributed to William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1745–1755. Walnut. H. 29 5/8"; Diam. of top: 34 3/4". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; purchased with

the Haas Community Fund and the J. Stodgell Stokes Fund.)

Tea table, eastern Virginia, 1750–1770. Mahogany. H. 27 1/8"; Diam. of top: 32 3/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Joseph Highmore, Mr. B. Finds Pamela Writing, England, 1743–1744. Oil on canvas. 25 5/8" x 29 7/8". (Courtesy, Tate Gallery, London/Art Resource, N.Y.) This scene is based on Samuel Richardson’s popular novel, Pamela (1740). According to Charles Saumarez Smith, “Pamela is shown in a space which she is clearly able to treat as her own with writing implements on the table in front of her; but her private space is invaded by Mr. B.” The tilt-top table is clearly the central fixture in Pamela’s specifically feminine space.

Gawen Hamilton, Family Group, England, ca. 1730. Oil on canvas. 28 1/2" x 35 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Tea table, probably Williamsburg, Virginia, 1710–1720. Walnut. H. 27 1/2", W. 26 1/2", D. 21 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) This is one of the earliest tea tables from the colonial period. It has finely turned columnar legs and an edge molding nailed to the top rather than being set into a rabbet.

Joseph van Aken, An English Family at Tea, ca. 1720. Oil on canvas. 39" x 45 3/4". (Courtesy, Tate Gallery.) The rectangular tea table illustrated in this painting has an applied edge molding, shaped skirt, and angular cabriole legs.

Tea table, possibly from the shop of Peter Scott, Williamsburg, Virginia, 1725–1740. Mahogany. H. 26 3/4", W. 29 1/2", D. 17 3/8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Nicolaas Verkolje (1673–1746), Two Ladies and a Gentleman at Tea, 1715–1720. Dimensions not recorded. (© V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London, www.vam.ac.uk) Art historian Peter Thornton notes that small oval tables like the one depicted in this scene were very popular in Holland. “Such forms often had a painted top which was hinged on a tripod pillar, so that when not in use, it could be placed close to the wall where it provided colorful decoration” (Authentic Décor: The Domestic Interior, 1720–1920 [New York: Viking, 1984], p. 79, no. 95).

Tea table, Philadelphia area of Pennsylvania, ca. 1720. Walnut and cherry. H. 27 1/8"; Diam. of top: 31 5/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Candle stand, Philadelphia, 1710–1720. Walnut. H. 28 7/8", W. 17 3/4", D. 16 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tea table, Philadelphia, 1730–1740. Mahogany. H. 28"; Diam. of top: 29 1/4". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; gift of Lydia Thompson Morris.)

Tea table with carving attributed to the shop of Samuel Harding, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1735–1745. Mahogany. H. 27"; Diam. of top: 31". (Courtesy, Diplomatic Reception Rooms, U. S. Department of State.)

Tea table attributed to Peter Scott, Williamsburg, Virginia, 1740–1750. Mahogany. H. 28 3/4"; Diam. of top: 32 13/16". (Courtesy, Robert E. Lee Memorial Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

View of the Dominy shop showing a table top mounted on a lathe. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) The Dominy family shop was located in East Hampton, Long Island.

Tea table, probably Norfolk, Virginia, 1760–1775. Mahogany. H. 28 3/4"; Diam. of top: 29 3/4". (Collection of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) This tea table probably represents the work of a cabinetmaker, a turner, and a carver.

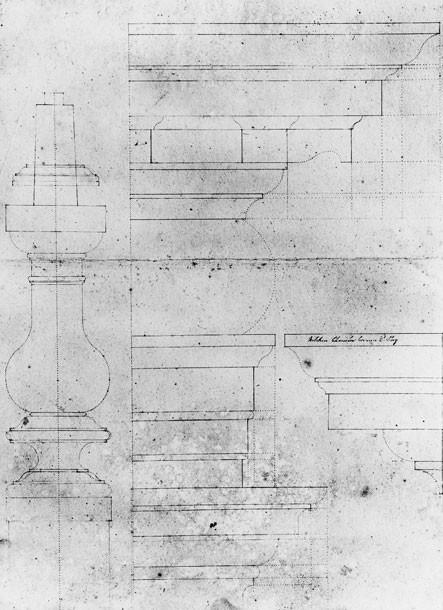

Thomas Hayden drawing of a baluster for a tilt-top tea table, Windsor, Connecticut, 1787. Dimensions not recorded. Ink on paper. The Great River: Art and Society of the Connecticut Valley, 1635–1820, edited by Gerald W. R. Ward and William N. Hosley, Jr. (Hartford, Conn.: Wadsworth Atheneum of Art, 1985), p. 225.

Tea table, Newport, Rhode Island, 1760–1770. Mahogany. H. 26 5/8"; Diam. of top: 31 7/8". (Photo, Israel Sack, Inc.)

Detail of three balusters in Touro Synagogue, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1763. (Courtesy, Touro Synagogue; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

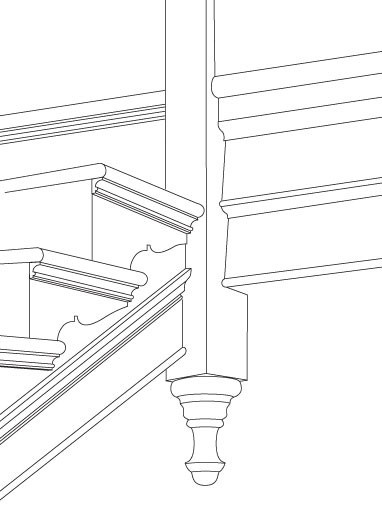

Detail of a pendant in the George Wythe House, Williamsburg, Virginia, 1750–1755. (Redrawn from an original by Singleton Peabody Moorehead; courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Tea table, New York, 1760–1770. Mahogany. H. 29"; Diam. of top: 29". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tea table, New York, 1760–1770. Mahogany. H. 29"; Diam. of top: 29". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the pillar of the tea table illustrated in fig. 20.

Detail of the pillar of the table illustrated in fig. 21.

Tea table with carving attributed to the shop of James Reynolds, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1766–1775. Mahogany. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; photo, Christie’s.)

Tea table with carving attributed to Bernard and Jugiez, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770–1775. Mahogany. H. 29 3/4"; Diam. of top: 31 1/2". (Courtesy, Dietrich American Foundation.)

Tea table, probably Boston, Massachusetts, 1750–1765. Mahogany. H. 27 1/2"; Diam. of top: 36". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

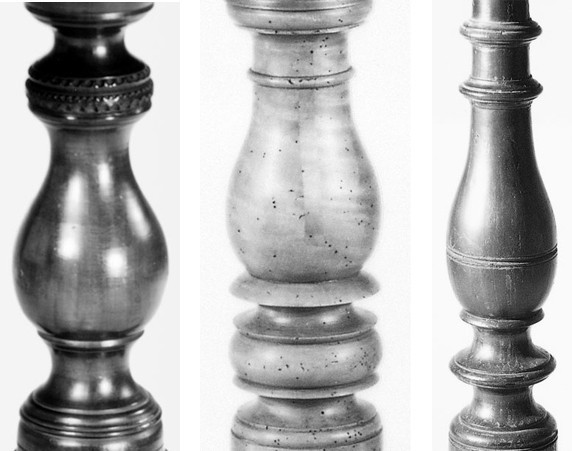

Detail showing the pillars on (from left to right): tea table, Boston or Salem, Massachusetts, 1760–1770; tea table, Newport, Rhode Island, 1760–1780; tea table, eastern Virginia, 1750–1770. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; John Nicholas Brown Center for the Study of American Civilization; private collection, photo, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Detail showing the pillars on (from left to right): tea table, Massachusetts, 1750–1770; tea table, Newport, Rhode Island, 1755–1775; tea table, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1740–1755; tea table, eastern Virginia, 1750–1770. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, gift of Mrs. H. K. Estabrook, photo, David Bohl; Philadelphia Museum of Art; Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Detail showing the pillars on (from left to right): tea table by Theodosius Parsons, Windham, Connecticut, 1787–1793; tea table, Pennsylvania, 1760–1780; tea table, Norfolk, Virginia, 1765–1775. (Courtesy, Mabel Brady Garvan Collection, Yale University Art Gallery; Winterthur Museum; Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Tea table, Norfolk, Virginia 1765–1785. Mahogany. H. 29 1/2"; Diam. of top: 37". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Tea table by Theodosius Parsons, Windham, Conecticut, 1787–1793. Cherry. H. 27 3/8"; Diam. of top: 36 1/4". (Courtesy, Mabel Brady Garvan Collection, Yale University Art Gallery.)

Detail showing the scalloped tops on (a) tea table, probably Connecticut, 1765–1785; (b) tea table, New York, 1765–1785; (c) tea table, Philadelphia, 1765–1775; (d) tea table, Charleston, South Carolina, 1760–1770. (Courtesy, Milwaukee Art Museum, Layton Art Collection; Chipstone Foundation; Winterthur Museum; Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Detail showing the legs of (from left to right): tea table, Virginia, 1750–1770; tea table, Philadelphia, 1765–1775. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Tea table, Charleston, South Carolina, 1760–1770. Mahogany. H. 28 1/2"; Diam. of top: 31 1/4". (Collection of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Tea table attributed to a member of the Chapin family, Hartford or East Windsor, Connecticut, 1775–1790. Cherry. H. 29 1/4"; Diam. of top: 31 1/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Eliphalet Chapin (1741–1807) worked as a journeyman in Philadelphia in the 1760s. When he returned to his native Connecticut, he continued to use construction features, proportions, and decorative details common in Philadelphia. His work influenced his cabinetmaker family members, Amzi (1768–1835) and Aaron (1753–1838).

Tea table, probably Newport, Rhode Island, 1750–1780. Mahogany. H. 28 1/4"; Diam. of top: 33". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Tea table, Newport, Rhode Island, 1760–1780. Mahogany. H. 27 1/2"; Diam. of top: 33 5/8". (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) Most Newport tea tables that appear to have been exported are relatively plain. It is doubtful that venture cargo shipments included elaborate examples like those occasionally made for Rhode Island patrons.

Desk, Newport, Rhode Island, 1760–1770. Maple with chestnut and tulip poplar. H. 40 7/8", W. 38 3/8", D. 20 7/16". (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Tea table, Chester County, Pennsylvania, 1788. Walnut, maple, ash, and lightwood inlay. H. 27"; Diam. of top: 23 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Epergne by William Cripps, London, 1759/60. Silver. H. 15 3/4", L. 26 1/4", W. 26". (Courtesy, Colonial Wiliamsburg Foundation.)

Robert West, Thomas Smith and His Family, Britain, 1733. Oil on canvas. 35 1/8" x 23 3/8". (Courtesy, National Trust Photographic Library/ Upton House, Beardstead Collection; photo, Angelo Hornak.)

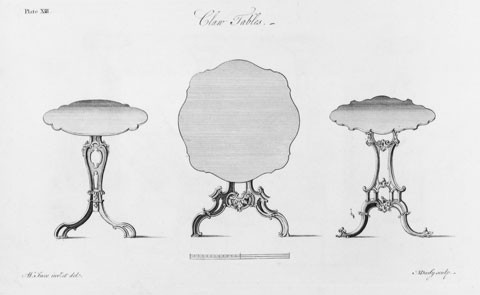

Designs for “Claw Tables” illustrated on plate 13 of the 1762 edition of William Ince and John Mayhew’s The Universal System of Household Furniture. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection.)

Tea table, Philadelphia, 1765–1775. Mahogany. H. 28 1/2"; Diam. of top: 36 1/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carving on the pillar of the tea table illustrated in fig. 43.

Tea table attributed to the shop of Peter Scott, Williamsburg, Virginia, 1765–1775. Mahogany. H. 28"; Diam. of top: 31 1/4 ". (Collection of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Kettle stand attributed to the shop of Peter Scott, Williamsburg, Virginia, 1765–1775. Mahogany. H. 31 1/4"; Diam. of top: 21". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the top of the kettle stand illustrated in fig. 46.

Tea table with carving attributed to Bernard and Jugiez, ca. 1765. Mahogany. H. 28 3/8"; Diam. of top: 36". (Kaufman Americana Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a leg on the tea table illustrated in fig. 48.

Tea table, probably Charleston, South Carolina, 1765–1775. Mahogany. H. 28 3/8"; Diam. of top: 29 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Detail of a leg on the tea table illustrated in fig. 50.

Similar creamware plates with different decorative treatment. (Left) probably Staffordshire, ca. 1775–1785; (right) possibly Leeds, ca. 1780–1790. (Courtesy, Audrey and Ivor Noël Hume; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Perhaps no single piece of American cabinetware of the Georgian period is so universally admired, so eagerly sought after by collectors . . . as a tripod tea table fabricated of rich grained wood, skillfully elaborated with a scalloped top cut from an individual part of solid crotch mahogany, ball-and-claw feet, and . . . various ornamentations on the pedestal and legs.

—William McPherson Hornor, Jr.

Few American furniture forms are more iconic than the tilt-top tea table. Over the years, antique dealers, curators, and collectors adopted their own language for the features of these tables that were most valued in the modern marketplace. Circular tops with carved edges—usually called “scallop’d” in the eighteenth century—acquired the name “piecrust,” and the mechanism that allowed the tops of some tables to tilt up into a vertical position, rotate, and be removed entirely—referred to as a “box” by many colonial tradesmen—became known as a “birdcage.” These and other stylistic and structural features attracted some collectors, while large tops made of highly figured mahogany or tables with histories of ownership in prominent colonial families captivated others. Today, tilt-top tea tables are in virtually every major collection of eighteenth-century American furniture, and they remain in great demand. Indeed, in 1986, a Philadelphia tilt-top tea table was the first piece of American furniture to exceed $1,000,000 at auction.[1]

Despite this long-standing admiration of tilt-top tea tables, their initial development in the eighteenth century, their subsequent rise to popularity, and their importance as cultural texts remains largely unexplored. Documentary sources and surviving tables suggest that the arrival and proliferation of this new form were inextricably linked to changes in the economy, increased Atlantic trade, and accelerating consumerism that emerged among the middle ranks of English society. By the mid-1730s, middle-market tilt-top tables like those made in London and the outlying provinces began appearing in well-to-do American homes. Associated from the start with genteel social interactions—especially tea drinking—tilt-top tables became indispensable components of fashionable parlors and symbols of status and refinement for politicians and planters as well as artisans and laborers. Furniture historians have traditionally studied tilt-top tea tables as landmarks of eighteenth-century cabinetmaking. In contrast, this article will address the tilt-top tea table in cultural context by investigating the circumstances that propelled it to the forefront of fashion and exploring the effects of its arrival on consumer behavior and social life.

New Tables

From the outset, tilt-top tables looked very different from conventional tables (fig. 1). Dining tables, dressing tables, and rectangular tea tables have joined frames, fixed tops, and four or more legs, whereas tilt-top tables typically feature a single pillar supported by three legs. Although people generally invent new types of furniture to accommodate changing needs, this novel table form gained popularity more for its appearance than its utility. Undeniably, tilt-top tables were versatile and useful. Their tops tilted up and down on battens (fig. 2), and many had castors making them easier to move and store. Also, tables with box mechanisms could be oriented so the tripod feet either fit into the corner of a room or along a wall. Tables that changed shape to save space, however, were by no means a new invention. For centuries Europeans had been making tables with falling leaves, foldable frames, and removable tops. A tripod table with a tilting top did not offer considerably more convenience. It was simply a new solution to the old problem of spatial efficiency. Why did English colonists in the 1730s want a new type of table? What social, psychological, economic, or aesthetic needs did tables with central pillars, tripod legs, and tilting tops fulfill? How did their success change the way people interacted or experienced life inside their houses?[2]

To answer these types of questions, scholars from several fields have demonstrated the benefits of studying both production and consumption. Consumption has been a popular topic of inquiry since 1982 when social historians Neil McKendrick, John Brewer, and J. H. Plumb used the phrase “consumer revolution” to describe the increased demand for a growing variety of goods among eighteenth-century residents of the British Atlantic world. Starting in 1675, ownership of domestic goods increased dramatically in England. Scholars have shown that middling artisans and farmers owned goods that their grandparents would have considered luxuries: forks, table knives, linens, mirrors, books, and of course, tea cups and tea tables. Many factors contributed to this increase, including cheaper production due to technological advances, improved transportation, and less hierarchical political climates. As historian Gloria Main has written, “a major change did take place during the eighteenth century [among] ordinary people—in their style of life as well as their standard of living.”[3]

Objects experts and material culture scholars who traditionally focus on modes of production have also emphasized in recent years the need for studying consumption. Social historian Cary Carson’s memorable mantra, “Demand came first!” has inspired innovative rethinking about the hand-in-hand development of consumer desire and new production. Other scholars have emphasized the importance of studying all the parties who create an object and assign it cultural meaning. In these studies, exploring human motivation rather than quantifying artifactual evidence becomes the intellectual goal.[4]

The tea table occupied a potent position in the imagination of eighteenth-century consumers. The social ritual of tea drinking, made popular by the English elite beginning in the 1680s, was increasingly affordable and widespread in the colonies after the turn of the century. It became a venue for a new genteel code of conduct that spread throughout the middling social ranks over the course of the eighteenth century. This set of polite manners emphasized physical cleanliness, graceful deportment, and pleasant conversation. It was a model of how people should treat one another that allowed individuals from different social backgrounds to comfortably interact according to a shared set of rules. In the common imagination, the ritual of tea drinking was frequently identified by the tea table itself. For instance, a Philadelphia advertisement for “so very neat” pewter tea wares began “To all Lovers of Decency, Neatness and Tea-Table decorum.” Here, “tea table” functioned as a metonym that succinctly denoted politeness. Rather than using the words “refined” or “fashionable,” this retailer and many others used the tea table to associate their products with the genteel lifestyle.[5]

Other advertisements further demonstrate the centrality of the tea table in the imaginations of refined consumers. Retailers selling imported stoneware and porcelain teawares suggested that customers purchase “blue and white tea table setts” or “a genteel tea table sett.” Rather than being identified as “tea sets” or “tea drinking vessels,” the ceramic wares were described as being of the table. The tea table, more than the teapot or the tea cup that rested on its surface, was the object by which the ritual gained recognition and acceptance. In other words, the piece of furniture around which people gathered to entertain each other with wit and flirtation became the signifier of that particular mode of interaction. The tea table was as much an idea as a particular piece of furniture. As luxurious dining equipage previously restricted to the wealthy and powerful became increasingly affordable, all the excitement of fashionable social gatherings became bound up in one item—the tea table.[6]

In addition to being a primary signifier of gentility, the tea table also connoted a “new female gentility” (fig. 3). As historian David S. Shields has demonstrated, women brought social tea drinking into the home in the first decades of the eighteenth century. Originally, tea drinking and its associated rituals of visits and lively conversation provided the wives of socially prominent husbands an entré into the public sphere. The “brash honesty” that characterized tea table discussions constituted a sort of circumspection that effectively policed the actions of the powerful and elite by threatening to expose scandal and subject any wrong-doers to ridicule. Critics of the ladies’ new power used the tea table much like advertisers to succinctly identify a mode of interaction—in this case, frivolous gossip between women. “Tea table chat” was frequently disparaged in newspapers, books, and private accounts by men whose authority felt threatened.[7]

Open criticism of gossip did not hinder the widespread embrace of tea table interactions by either gender. Through the eighteenth century, more and more people learned the ins and outs of the tea drinking ritual, which existed in countless variations in different towns and cities. The tilt-top tea table probably contributed to tea’s popularity because it facilitated lively interactions among guests while maximizing opportunities to display refinement. A circular table—effectively the social stage—provided spatial parity to all players. No one dominated from the head of the table and no one “sat below the salt.” In addition, a table with a central pillar rather than traditionally joined legs created open spaces for ladies to display their silk brocaded skirts, and for men to elegantly cross their legs and show off their stockinged calves. No vertical table legs obscured a person’s clothing or posture, both primary means for display in the eighteenth century (fig. 4).[8]

Of course, early Americans owned several different kinds of tea tables. In addition to the circular tilt-top tables there were joined rectangular examples with molded tops. Both versions were frequently called “tea tables” in documents, making their relative popularity and use difficult to decipher. Rodris Roth suggested that the circular tea tables enjoyed greater popularity than rectangular versions. Roth based her statement on the frequent appearance of tilt-top tables in prints and paintings from the era. An equally subjective piece of evidence is the much greater number of circular tea tables that survive in comparison to rectangular versions. Though impossible to pin-point, the popularity of the tilt-top table probably stemmed in part from its unusual form that departed dramatically from traditional table construction. This novelty makes it an informative cultural text carrying significant meaning for the historian.[9]

Inception and Arrival

During the 1680s, European joiners began mounting tea trays imported from the Far East on joined frames. This probably led to the production of rectangular tea tables, the earliest of which had turned (fig. 5) or scrolled legs. London joiners probably began making examples with cabriole legs (fig. 6) by the late 1710s, but the earliest American examples appear to date from the 1720s (fig. 7). Tilt-top tables probably developed as a hybrid of different forms. Candle stands with central pillars and fixed tops were popular in Europe during the seventeenth century. Elaborate versions with carved and gilded surfaces were often made in pairs. In court or other elite settings, they typically flanked a central table and mirror in the French-inspired ensemble sometimes called the “triad.” The inventory of James Brydges, first Duke of Chandos, listed a “large Tea Table cover’d with silver” with a pair of stands to match valued at £750. British craftsmen may have modified their stand designs by adding round, table-sized tops during the early eighteenth century. Dutch artisans began producing tables with central pillars and relatively large, oval tilting tops somewhat earlier (fig. 8). These distinctive forms were conceptual forerunners of the British tilt-top tea table. Given the considerable amount of travel and stylistic exchange between Holland and England during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, it is conceivable that British artisans borrowed the idea of a tilting top from Netherlandish sources and adapted it to their own stand or table forms.[10]

Most English appraisers, merchants, and tradesmen used the term “pillar and claw” to describe tilt-top tea tables (the word “claw” designated the three legs). Other common nomenclature included “claw table” and “snap table,” an onomatopoetic name inspired by the catch that held the top in a horizontal position. One of the earliest American references to this form is in the probate inventory of Captain George Uriell (d. 1739) of Anne Arundel County, Maryland. His household possessions included “two Mohogany Claw Tables” worth £3.3. Documentary references increased during the following decades. The inventory of a Charleston man taken in 1740 listed “one round mahogany claw foot table.” Five years later, Philadelphia cabinetmakers Joseph Hall and Henry Rigby advertised a “Pillar and Claw table” and an “old Pillar & Claw Mahogy Table.” The qualifier “old” implies that the table was made well before 1745.[11]

Some colonists struggled to describe this new furniture form. In 1749 appraisers for the estate of John Calder of Wethersfield, Connecticut, referred to his tilt-top tea table as a “stand” with a “fashion swivel leaf.” In this context “fashion” probably meant “modish” or “stylish.” “Stand table” was used throughout the colonies, most consistently in Wethersfield and Rhode Island. Many appraisers alluded to the kinetic action of the top in describing these tables. The 1757 estate inventory of Boston merchant Peter Minot, for example, listed a “Mahogany Turn up Table.”[12]

“Tea table” with no qualifier was the most common name for the tilt-top variety in British North America. References to “tea tables” occur in advertisements and inventories from the first quarter of the eighteenth century, but they probably denoted rectangular forms. During the 1730s, the term became more ambiguous as it was increasingly applied to circular as well as rectangular tea tables. This shift is evident in merchant advertisements that offer iron and brass “tea table ketches.” Occasionally appraisers, merchants, and artisans differentiated between circular and rectangular tea tables. An inventory taken in Savannah, Georgia, in 1768 lists “1 Mahogany Tea Table Round” valued at one pound. Some regions adopted consistent habits of nomenclature. People in Philadelphia tended to call rectangular tea tables “square.” A lack of descriptive language generally implied a tilt-top form in that city. The fact that Americans consistently used “tea table” rather than “pillar and claw table” or other English terms may suggest a more common association among colonists between tilt-top tables and tea drinking.[13]

The earliest surviving American tilt-top tea table was made in the Philadelphia vicinity and probably dates from the 1720s (fig. 9). Its pillar turnings, faceted base block, and flat-sided cabriole legs appear to be just one step removed from the baroque stand illustrated in figure 10. Moreover, the use of a wrought iron catch rather than an imported brass one suggests that the latter hardware was not readily available when the table was made. Another tea table with a faceted base block survives (fig. 11), but it was probably made a decade later. Its rounded legs, pad feet, and columnar pillar illustrate the transition in Philadelphia from baroque Netherlandish designs toward the tilt-top table form that became popular among English consumers. By the early 1740s, at least one Philadelphia shop was producing relatively uniform tilt-top tables (fig. 12). Examples in this group typically have complex tops with up to twelve repeats, inverted balusters, and battens with short cross pieces that fit snugly around the top board of the box.

The production of tilt-top tea tables increased during the following decades throughout the colonies. Some colonial cabinetmakers made examples that rivaled those of their London counterparts. Williamsburg, Virginia, cabinetmaker Peter Scott began producing highly sophisticated tilt-top tables about 1745. An elaborate example that descended in the Lee family of Stratford Hall (fig. 13) may have served as a model for tables that he made for other prominent Virginia families. A walnut tilt-top tea table labeled by Philadelphia cabinetmaker William Savery (fig. 1) is roughly contemporary with Scott’s but has no carving on the top or pillar. This pair illustrates that elaborately carved and relatively plain tilt-top tables were being made simultaneously in the 1740s.[14]

Production

The patterns of production and distribution of tilt-top tables within the colonies indicate that they were being built inexpensively for a mid-level market. Making a tilt-top table required turning skills and the ability to perform simple joinery. In addition to the pillar, the turned components on a tilt-top table could include colonettes or miniature balusters if the object had a box and the top if it had a scalloped or molded edge. Because such tops were too large to be turned over the bed of the lathe, they were typically mounted on an arbor and cross (fig. 14). Some tables represent the work of a single artisan whereas others are the products of several tradesmen (fig. 15).[15]

Growing demand in this era encouraged specialization and collaboration between artisans. In the seventeenth century, English craftsmen and traders challenged Dutch dominance of the Atlantic market by espousing mercantilism, a system of commercial trade that took advantage of English holdings in America and the Caribbean. The success of this carrying trade convinced English tradesmen as well as the Crown that making and marketing goods efficiently and selling them inexpensively to middle range consumers could yield substantial profits. Glenn Adamson has demonstrated that caned chairs made first in London and later in Boston between 1700 and 1730 pioneered a mercantilist production strategy in America. Caned chair makers imitated the carved crests and front stretchers that were fashionable among the late seventeenth-century elite. They could sell them inexpensively, however, by buying the stretchers and stiles in large number from specialist turners who made them quickly and efficiently. Merchants then sold the caned chairs throughout the Atlantic rim to consumers hoping to ally themselves with their fashionable counterparts in London.[16]

Artisans on both sides of the Atlantic recognized that focusing production and cooperating with other specialists made all of their jobs easier, reduced their costs, and raised their profits. Tilt-top tables, whose parts required distinct sets of skills and tools, lent themselves to collaborative production. Documentary records indicate that turners sold and traded tilt-top table pillars and tops on the open market much like caned chair makers had traded stiles and stretchers in previous decades. In the May 30, 1751, issue of the Pennsylvania Gazette, Joseph Pattison, “Turner from London,” directed his advertisement for “tea table tops, and tea boards, pillars, balusters” to other artisans. In 1754 Joshua Delaplaine, a New York carpenter, joiner, and merchant, bought three “pillers of Mahogany” from John Paston and sold “a mahogany round tea table” to Samuel Nottingham, Jr. The account book of Charleston cabinetmaker Thomas Elfe documents a similar business relationship with turner William Wayne. In September 1771 Elfe paid Wayne £1.10 for “2 tea table pillars & turning.”[17]

Some craftsmen traded tilt-top table parts over considerable distances. Beginning in 1766 Samuel Williams repeatedly advertised “mahogany and walnut tea table columns” and “mahogany tea table tops” for local use or for “exportation.” This suggests that he sold components to merchants engaged in the venture cargo trade. On June 10, 1784, Solomon Lathrop, a joiner in Springfield, Massachusetts, recorded “carrying 8 tea table pillars to Windsor,” about fifteen miles away. By the second half of the eighteenth century, the demand for tilt-top tea tables and other furniture forms had become sufficient to sustain specialization and collaboration in rural areas.[18]

Most artisans who routinely produced tilt-top tables probably kept parts on hand to be assembled on short notice. Large cabinet shops in Britain often stockpiled sizable quantities of standard components. The 1763 inventory of London carver, cabinetmaker, and upholsterer William Linnell listed “38 setts of claws for pillar and claw tables” and “4 setts of carved table claws Do.” Similarly, Philadelphia joiner Joshua Moore had “13 tea table pillars” and “1 Tea Table top” at his death in 1778.[19]

Some turners sustained their businesses by making pillars for uses other than tilt-top tables. At least two baluster-shaped tilt-top table pillars have been connected to craftsmen involved in architectural construction. In 1787 Thomas Hayden of Windsor, Connecticut, rendered a cross-section drawing of a baluster-and-ring pillar for a tilt-top table on the same page as plans for architectural cornice moldings (fig. 16). William Hosley and Philip Zea have attributed one table with an identical pillar to Hayden and suggest that he may have made the drawing as a guide to local craftsmen producing similar tables. Patricia E. Kane and Wallace Gusler have established more tangible links between furniture and architectural turnings. Kane has shown that the pillar on one Newport tilt-top table (fig. 17) matches the balusters on the second floor of Touro Synagogue (built 1763) (fig. 18), and Gusler has demonstrated that the pendant on the Peter Scott table illustrated in figure 13 is similar to those in the George Wythe and Galt houses in Williamsburg, Virginia (fig. 19).[20]

Some artisans who produced tilt-top table parts began their careers in the chair making trade. William Savery apprenticed with Solomon Fussell, a Philadelphia chair maker who maintained a large shop that produced seating in competition with Boston exports. Fussell made both joined and turned chairs and bought seat lists and slats from specialists outside his shop. By the time Savery completed his apprenticeship in 1741, he would have known how to assemble chairs using parts obtained from other craftsmen. Even though he continued to work at the “Sign of the Chair,” Savery broadened his repertoire by making tables and case furniture. Tilt-top tables may have been one of the first new forms he produced since they could be made quickly and easily using piecework, possibly pillars and tops furnished by the same turners who sold him and his master chair components. The requisite hardware was readily available from Fussel who advertised “brass tea table catches” in 1755.[21]

Carved tables required additional collaboration. Some large cabinet shops had workforces that included cabinetmakers, turners, carvers, and other specialists. Regrettably, cabinetmakers’ account books rarely specify whether a tradesman was a shop employee or an independent contractor. For instance, Thomas Elfe paid Thomas Burton seven pounds “for Carving a Pillar and Claws” in 1771, but the nature of their business relationship remains unclear. Evidence suggests, however, that cabinetmakers making tables and other furniture for wealthy customers went to great lengths to secure skilled carvers. In the May 31, 1762, issue of the New York Mercury, immigrant “Cabinet and Chair-Maker” John Brinner reported that he had “brought over from London six Artificers” and offered:

all sorts of Architectural, Gothic, and Chinese, Chimney Pieces, Glass and Picture Frames, Slab Frames, Gerondoles, Chandaliers, and all kinds of Mouldings and Frontispieces, &c. &c. Desk and Book-Cases, Library Book-Cases, Writing and Reading Tables, Commode and Bureau Dressing Tables, Study Tables, China Shelves and Cases, Commode and Plain Chest of Drawers, Gothic and Chinese Chairs; all Sorts of plain or ornamental Chairs, Sofa Beds, Sofa Settees, Couch and easy Chair Frames, all Kinds of Field Bedsteads

Philadelphia cabinetmaker Benjamin Randolph also imported labor from England. His principal carvers—John Pollard and Hercules Courtenay—trained in major London shops, signed indentures to pay for their passage to the colonies, and established their own businesses after their terms had expired. It is unlikely that either Randolph or Brinner required much outside labor when their shops were fully staffed.[22]

Luke Beckerdite has identified a group of four New York tilt-top tables that were made in one large cabinet shop but carved by four different artisans. Two of the tables (figs. 20-23) were clearly carved in the same shop because the tradesmen who decorated each of them collaborated on a chimneypiece in Van Cortlandt Manor. Although Beckerdite theorized that all four tables may have been produced and carved under the same roof, it is also possible that they are the products of a single cabinet shop and three independent carving firms, one of which employed two hands.[23]

Even the largest cabinet shops occasionally required piecework or services from specialists. Randolph’s competitor Thomas Affleck commissioned carving from independent artisans, particularly James Reynolds (fig. 24) and the firm Bernard and Jugiez. The tea table illustrated in figure 25 has carving attributed to Bernard and Jugiez, and its pillar has details that relate to those on firescreens that Affleck made for Philadelphia merchant John Cadwalader.[24]

Dispersal

Between 1740 and 1790 tilt-top tea tables became nearly ubiquitous fixtures in American parlors and drawing rooms. Their increased production coincided with a substantial escalation of travel and trade throughout the British Empire in the 1740s and economic prosperity in the Americas. Historians John J. McCusker and Russel R. Menard have argued that the colonial economy grew in two spurts. The first spurt directly followed initial settlement in the seventeenth century. The second spurt, which began in the 1740s and continued until the Revolutionary War, coincides with the spreading popularity of tilt-top tea tables. After almost a century of “stagnation,” the colonial economy began offering people more opportunity for financial gain than the English economy. More people in the colonies became involved in harvesting, transporting, and selling foodstuffs and raw materials from America to Europe. As their assets grew, these colonists developed a desire for fashionable household goods including new forms like the tilt-top table.[25]

The economic boom lured not only merchants but also ambitious craftsmen prepared to profit from increased demand. Among these were cabinetmakers, joiners, turners, and carvers trained in British urban centers and in the provinces. Immigrant artisans arrived with distinctive stylistic vocabularies and work habits. This led to the dispersal of leg profiles, pillar shapes, and construction details characteristic of many British shop, town, city, and regional furniture making traditions. For example, pillars with spiral-fluted urns occur on tables made in eastern Massachusetts, Newport, Rhode Island, and eastern Virginia (figs. 26, 27). This motif crossed the ocean with English furniture makers who frequently turned spiral-fluted urns on pillars for tilt-top tables as well as bedposts and other forms. Newport absorbed large numbers of English immigrants after the Seven Years’ War ended in 1763, and Norfolk was a much larger city where the majority of craftsmen either had trained in England or with an English master. It is equally plausible that British tilt-top tables themselves inspired the design for spiral-fluted urns, particularly in the Boston-Salem area where imported furniture had a strong influence on local production.

Similarly, tilt-top tea tables with plain columnar pillars and baluster shaped pillars survive from nearly every port city in America (figs. 28, 29). Both of these ubiquitous turnings have clear British precedents (see figs. 3, 4, 41), but, like the spiral-fluted urn pattern, they display considerable variety in shape, proportion, and molded detail (see figs. 1, 11, 30, 31).[26]

As a result of furniture importation and immigration, many generic tilt-top tables made in the North American colonies looked more alike than different. Not only did similar turned pillars appear hundreds of miles from each other, but tables made throughout the colonies also shared the same basic top and leg designs. Tables with plain tops, turned tops, and scalloped tops (fig. 32) were made from New England to Charleston. Most artisans who produced tilt-top tea tables used dovetails to attach the legs to the pillar rather than to a base block like the examples shown in figures 9 and 11. Although the legs on tilt-top tea tables display considerable variation in shape, arch, and splay, most fall into two basic categories: those with strong cyma shapes and high arched knees, and those with weaker cyma shapes and relatively flat knees (fig. 33).

Of course, variations from shop to shop and region to region do exist. Some Charleston tables (fig. 34) resemble English examples more closely than those from other American cities, whereas many Connecticut tables combine designs commonly found in Philadelphia (fig. 35), New York, and Boston. A small group of Newport tables even deviates from the standard pillar and claw design by incorporating multiple pillars or a cabinet with drawers (fig. 36). Despite these decorative differences, tilt-top tables of the same basic type were available to those who could afford them in all the American cities in the mid-eighteenth century.

The suggestion that similar tilt-top tables were made throughout the colonies challenges the regional differences traditionally catalogued by furniture historians. In “Regionalism in Early American Tea Tables,” furniture scholar Albert Sack suggested that artisans in each colony made pillar forms specific to their location. To some degree, Sack is correct. Tables similar to the ones he illustrated certainly do survive from the regions he indicated; however, more specific information is usually needed to pinpoint a table’s place of origin. More importantly, the pillars, tops, and legs shown in figures 27–29, 32 and 33, point out that reality often defies regional categorization. An approach focused on the people who made and used tilt-top tables—rather than the tables themselves—yields a more complex story of trans-Atlantic migration and trade.[27]

Like chairs, which could be produced quickly and economically using specialized labor and piecework, tilt-top tables were perfectly suited for the furniture export trade. Following the model established by Boston tradesmen, merchants, and ship captains during the 1720s, sea-faring entrepreneurs increasingly carried raw materials and finished goods between ports in England, North America, and the West Indies. A Rhode Island tea table that descended in the family of Wilmington, North Carolina, Judge Joshua Grainger Wright (fig. 37) may have been exported by a Newport Quaker merchant who maintained business ties with Friends communities in North Carolina. A similar Newport table was probably carried to Berwick, Maine, around mid-century and sold to the father or grandfather of Ichabod Goodwin.[28]

The Wright and Goodwin tables resemble examples with plain columnar pillars from England, Newport, Norfolk, and elsewhere. Patricia E. Kane has argued that some Newport furniture makers developed standardized models exclusively for the export market. Some Newport tradesmen referred to tilt-top tea tables as “fly tables.” In 1758 Job Townsend, Jr., charged Isaac Elizer forty-five pounds for “a Mohogony Fly Table with a Turned Top.” Over the next two years Elizer bought two additional fly tables and four tea boards, which suggests that he may have acquired them for export. “Fly tables” appear frequently in other Newport records, especially in the early 1760s when merchant activity was at its height in that city.[29]

Historians have demonstrated that Newport artisans such as John Cahoone and John Townsend made plain furniture—primarily desks, chests of drawers, and tables—to ship with merchants trading along the Atlantic coast and with the West Indies. The tilt-top tables that Kane identified as “standard models” fit in with this genre of work. Like the desk illustrated in figure 38, they were sturdy forms that could be assembled quickly and inexpensively through the use of piecework, patterns, and collaborative arrangements. The frequent appearance of tilt-top tables in venture cargo shipments also attests to the form’s popularity with mid-level consumers throughout the colonies.[30]

The correlation between increased production of tilt-top tables and economic growth in the colonies after 1740 may explain why tilt-top tables from Massachusetts survive in much lower numbers than those from more southerly areas. New England never took full advantage of the “burgeoning Atlantic economy” in part because the markets for their products grew much slower than the region’s rapidly increasing population. Agricultural land was becoming scarce, towns more crowded, and people in northern New England lived under constant threat of attack from the French and Native Americans who launched violent assaults on British settlements during King George’s War (1739–1748) and the Seven Years’ War (1756– 1763). These factors may have discouraged artisans from immigrating to the region and impeded the importation and local production of certain luxury goods including tilt-top tea tables.[31]

By the last quarter of the eighteenth century, artisans in rural areas and in non-English communities made tilt-top tables that mimicked mainstream urban versions. Were it not for the chip carved ring and unusually deep cove at the top of its pillar, a table with the label of Windham, Connecticut, furniture maker Theodosius Parsons could be attributed to almost any city or town (fig. 31). By contrast, the artisan responsible for the unusual form illustrated in figure 39 made an Anglo-American tilt-top table using Pennsylvania German construction and design sensibilities. The top is inlaid in traditional Pennsylvania German fashion with the owners’ initials and the date in lightwood stringing. The top tilts on hinged iron straps that are screwed to a large wooden cube at the top of the plain turned pillar, a creative interpretation of the conventional block or box. The tilt-top table had become sufficiently widespread among the rural populace that it crossed cultural boundaries.[32]

Consumer Choices

Timothy H. Breen has argued that the “challenge of the eighteenth-century world of goods was its unprecedented size and fluidity, its openness, its myriad opportunities for individual choice, that subverted traditional assumptions and problematized customary social relations.” As part of this world of goods, the novelty of the tilt-top table form and the choices it offered consumers suggest shifting needs, tastes, and buying habits.[33]

At its inception, the tilt-top table was a new aesthetic choice. When covered with a cloth, the tops of tilt-top tables almost seemed to float in space. Other domestic objects from the second and third quarters of the eighteenth century reflected similar aesthetic sensibilities. Delicate arms and feet (fig. 40) supported the center sections and cups of silver epergnes, and wineglasses and goblets rested on thin stems with double-helix twists.[34]

The tilt-top table form might be viewed as a quintessential anglo-American interpretation of the rococo, defined by Jonathan Prown and Richard Miller as a combination of “rational thought” and the “public articulation of unorthodox, hedonistic, and erotic forms of expression.” In some ways, the tilt-top tea table was symmetrical and ordered. Even when the top was tilted up, the table’s façade was visually balanced. On the other hand, the form communicated a degree of precariousness. A heavy item placed too close to the edge of the top could topple the whole structure to the floor. Judging from the number of tables with broken tops, pentil blocks, and boxes, this happened with considerable frequency. The tilt-top table’s simultaneous embodiment of order and unpredictability and its strong association with women potentially locate it in “rococo culture.” Certainly less expensive and more widely owned than the pedimented and carved high chests studied by Prown and Miller, the tilt-top table probably contributed to the spreading enthusiasm for a mainstream expression of imaginative forms.[35]

The tilt-top table retained its imaginative form through the eighteenth-century, but consumer preferences in decoration shifted. The tastes of some early American consumers were similar to those of their English counterparts. Many upper-class British patrons commissioned relatively simple tilt-top tea tables as the paintings illustrated in figures 3 and 4 suggest. Robert West’s painting of Thomas Smith and his family (fig. 41) depicts a tea table of the same basic design as the Savery one (fig. 1). Both objects have circular tops that are about as wide as the tables are high, boxes, simple columnar pillars, and graceful cabriole legs. Neither exhibit carving or any other significant decoration.

In the 1750s more wealthy American patrons commissioned elaborately carved tilt-top tables. An example that descended in the Wharton family of Philadelphia is one of the earliest with carved ornament (fig. 12). The shells and husks on its knees are associated with Samuel Harding, a prominent tradesman whose shop furnished much of the architectural carving in the Pennsylvania State House (Independence Hall). Although Harding’s birthplace is unknown, many of the carvers whose work is represented on existing tilt-top tea tables immigrated to the colonies during the third quarter of the eighteenth century. A large percentage arrived during the 1760s, attracted by the growth in America’s economy after the Seven Years’ War.[36]

English design books, including William Ince and John Mayhew’s The Universal System of Household Furniture (1759) and the Society of Upholsterers’ Genteel Household Furniture in the Present Taste (1760), illustrated “Claw Tables,” but the engravings bear little resemblance to American work (fig. 42). The bases of the English tables are extremely sculptural and organic, whereas those on most American examples simply have carved details overlaid on an otherwise conventional form. Some of the most elaborate English tables may have been constructed and decorated by carvers. American tables, in contrast, were usually made by cabinetmakers and carved by professionals working in the same shop or independently.

A tilt-top tea table that descended in the Eyre family of Philadelphia is one of the most refined examples made in the colonies (fig. 43). It has well-drawn and finely executed cabochons and leaves on the knees, a flower-and-ribbon motif on the astragal at the base of the pillar, and expressive foliage on the compressed ball above (fig. 44). Although the carving contributed greatly to the rich appearance of the table, it did not challenge the basic design formula. The shape of the legs, their attachment to the pillar, and the pillar design—a compressed ball surmounted by a slightly tapering column—have precise parallels in uncarved tea tables from the Philadelphia area. The same relationship between carved and uncarved forms can be observed on Philadelphia case furniture from the 1730s through the 1780s.[37]

The makers and sellers of tilt-top tables offered consumers several options, all of which affected price. The 1756 and 1757 price agreements from Providence, Rhode Island, listed “stand tables” in three woods. Mahogany tilt-top tables cost one and a quarter times more than walnut, which cost one and a quarter times more than maple. A similar ratio appears in the Philadelphia cabinetmaker’s price list of 1772.[38]

Size also influenced price. The Providence agreements indicated that “stand tables” were more expensive than “candlestands.” Similarly, the “tea table” section of the Philadelphia price list included a lower priced “folding stand,” which had a top less than twenty-two inches in diameter and could be made with or without a box. Thomas Elfe offered tops in five sizes priced from ten pounds to fourteen pounds at increments of one pound. He generally referred to the most expensive tilt-top examples as “large tea tables.”[39]

The idea that some craftsmen conceived of turned tops in incremental sizes with incremental prices is supported by entries in the account book of Job Townsend, Jr. He sold tea boards ranging from six to twenty inches in diameter, priced from £1.15 to twenty pounds. Townsend’s customers paid from ten shillings to several pounds extra for each additional inch. Although he did not sell turned tops individually, he owned a lathe and undoubtedly made them for the tilt-top tables he sold.[40]

Repetitive production and demand allowed furniture makers to establish standard prices for generic ornamental details such as “Leaves on the Knees” and “Claw feet.” Even elaborate carving like that on Peter Scott’s tea tables and kettle stands (see figs. 13, 45–47) could be offered as an option with a set price. This was especially true of objects constructed and carved in the same shop or made and decorated by tradesmen who collaborated regularly. In many instances, cabinetmakers simply added on charges for the carver’s labor. Thomas Affleck’s bill to John Cadwalader for eighteen major pieces of furniture made between October 13, 1770, and January 14, 1771, included references “To Mr. Reynolds Bill for Carving the Above £37” and “To Bernard & Jugiex for Ditto £24.”[41]

A tea table that reputedly belonged to Michael and Miriam Gratz of Philadelphia has legs with enormous C-scrolls and carving attributed to Bernard and Jugiez (fig. 48). The maker had to saw the legs from unusually thick stock to accommodate the scroll volutes, and the carver had to decorate the sides of the legs rather than just the top (fig. 49). This extra material and labor would have increased the price of this table significantly. In contrast, the C-scrolls on the legs of the South Carolina table illustrated in figures 50 and 51 may have been a standard option since they required minimal work.[42]

The fact that tilt-top tables were sold at different price levels locates them among other commodities that revolutionized the way people of middling wealth acquired stylish goods. Textiles were the first luxury household goods that came within reach of the non-elite. Over the course of the seventeenth century, laborers, artisans, and tradesmen who formerly could afford only woolens suddenly found themselves choosing between a bewildering array of weaves, colors, and decorative combinations. After textiles, other fashionable commodities began to follow this pattern. Stylish but relatively inexpensive leather chairs and caned chairs became available to members of the middle class, tin-glazed earthenware and refined stoneware emerged as alternatives to porcelain, and importers began selling green tea at cheaper prices to compete with Bohea tea in the 1710s. Although not widely popular in the colonies before the 1740s, the tilt-top table may have been the furniture form most successfully marketed to the middle class.[43]

Because of its distinct role as a consumer commodity affiliated with female gentility, the tilt-top table might be considered in the category of teaware rather than furniture. When choosing a tea table, consumers probably considered how it would complement their teapot, salver, spoons, and ceramics rather than other furniture they owned. Few tilt-top tables were made en suite with other furniture forms, with the possible exception of the Philadelphia examples that descended in the Stevenson family. Tilt-top tea tables, however, often have details that relate to those on teawares (figs. 46, 47). Consumers may have purchased tables with scalloped tops that complemented the edge treatment of salvers and tea boards or vice versa. Even the more modest dished tops had visual cognates in silver and brass trays and tazza.[44]

It is difficult to generalize at which point in their acquisition of requisite tea-related objects consumers chose to buy tea tables. Historians and archaeologists examining several geographic areas have suggested that colonists bought refined artifacts little by little as their funds allowed. Fittingly, it seems that middling consumers tended first to acquire the equipment required for brewing and consuming tea. Owning a few tea cups or a tea pot, however, did not necessarily indicate a full shift toward the genteel lifestyle. In contrast, buying a tea table—whose very name signified refinement—may have been a more meaningful choice. By all accounts, tilt-top tea tables cost more than ceramic tea wares. On the other hand, they tended to cost much less than silver teapots, kettles, and salvers. Many consumers were willing to spend more for their teawares than their tablewares. Evidence from the Chesapeake region suggests that some consumers bought porcelain teawares but could only afford creamware for their tables. By extension, middling families who may not have been able to afford a set of carved chairs or a looking glass may have purchased a tea table.[45]

The popularity of tilt-top tea tables may have helped spread the consumerist impulse that made possible later increases in stylish goods, most notably Wedgwood’s successful creamware. Creamware introduced a much less expensive type of polite ware to the ceramic market and also offered different types of decoration at varied prices (fig. 52). Consuming fashionable goods in considerable number was a new activity for the British middling ranks in the eighteenth century. It required a change in attitude and often a change in the patterns of daily life. When creamware appeared on the market in the late 1760s, the appetites of middle-class consumers were already whetted for tea-related objects that signified status but fell within their financial reaches. Within a decade, wealthy Americans as well as those with less financial wherewithal had replaced their old tea and table wares with the new type. The attitudes and infrastructure necessary for this rapid and total change in ceramic consumption patterns had been generated over the previous decades by a wide range of fashionable goods—calicos, forks, mirrors, and many others. Among these goods was the tilt-top tea table.[46]

Ironically, the success of creamware probably contributed to the eventual demise of the tilt-top tea table’s status. Craftsmen continued to make tripod tables through the Federal era (often with attenuated, neo-classical style legs and pillars) but they did not carry the same connotations. The tables that often signified wealth and status in the early nineteenth century were long segmented dining tables that filled large dining rooms and entertaining halls. Tilt-top tables may have lost their ability to communicate status when tea drinking and ownership of teawares—particularly creamware—became nearly ubiquitous after 1770. In the stores of Chesapeake retailers, creamware plates represented 73.3 percent of all plates sold in the 1770s, and 96.2 percent in the 1780s.[47]

In 1774 several colonial newspapers published rhymes titled “A Ladies’ Adieu to her Tea Table.” The poems all differed somewhat, but shared the patriotic fervor that led men and women throughout the colonies to boycott tea in protest of England’s high taxes. The abandonment of tea seemed to accompany a heavy heart, not for want of the drink but rather for the tea table accoutrements. “Farewell the Tea Board, with its gaudy Equipage, / Of Cups and Saucers, Cream Bucket, Sugar Tongs, / The pretty Tea Chest also, lately stor / With Hyson, Congo and best Double Fine.” By making these tea-related goods more widely available, the consumer revolution had engendered a desire for material objects among middling people faster than ever before. The tilt-top tea table was the product of its particular historical moment. Its production relied on the commercial trade networks that characterize the mid-eighteenth century, and its function and appearance not only facilitated but came to symbolize the fashionable modes of social interaction that changed daily life for so many. With changes in society and taste after the American Revolution, the tilt-top table lost its potency in the imaginations of American consumers.[48]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For their generous assistance and encouragement, the author thanks Glenn Adamson, Luke Beckerdite, Eleanore Gadsden, J. Ritchie Garrison, Dudley and Constance Godfrey, Wallace B. Gusler, Charles F. Hummel, Jack Lindsey, Ann Smart Martin, and Jonathan Prown.

William McPherson Hornor, Jr., “A Study of American Piecrust Tables,” International Studio 99, no. 411 (November 1931), 38–40, 78–79; Christie’s, New York, January 25, 1986.

For a discussion of tables that change shape, see Peter Thornton, Seventeenth-Century Interior Decoration in England, France & Holland (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1978), pp. 226–30; and Adam Bowett, English Furniture, 1660–1714 From Charles II to Queen Anne (Woodbridge, Eng.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2002), pp. 106–7.

Neil McKendrick, John Brewer, and J. H. Plumb, The Birth of a Consumer Society: The Commercialization of Eighteenth-Century England (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1982). Lorna Weatherill, Consumer Behavior and Material Culture in Britain, 1660–1760 (New York: Routledge, 1988), pp. 25–42. Lois Green Carr and Lorena S. Walsh, “Changing Lifestyles and Consumer Behavior in the Colonial Chesapeake,” in Of Consuming Interests: The Style of Life in the Eighteenth Century, edited by Cary Carson, Ronald HoVman, and Peter J. Albert (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1994), pp. 59–166. Gloria L. Main, “The Standard of Living in Southern New England, 1640–1773,” William and Mary Quarterly 45, no. 1 (January 1988), p. 127. Other recent volumes that address eighteenth-century consumerism include Consumption and the World of Goods, edited by John Brewer and Roy Porter (New York: Routledge, 1993); The Consumption of Culture, 1600–1800: Image, Object, Text, edited by Ann Bermingham and John Brewer (New York: Routledge, 1997); Richard Bushman, Refinement of America: Persons, Houses, Cities (New York: Vintage, 1992), p. 184.

Cary Carson, “The Consumer Revolution in British North America: Why Demand?,” in Of Consuming Interests, p. 486; Ann Smart Martin, “Makers, Buyers, and Users: Consumerism as a Material Culture Framework,” Winterthur Portfolio 28, nos. 2/3 (summer/autumn 1993), pp. 141–57.

Pennsylvania Gazette, March 15, 1733, Accessible Archives, item 1225. Unless otherwise noted, all further references to this newspaper are from Accessible Archives and only the date and item number will be cited. For a succinct discussion of politeness, see John Styles, “Georgian Britain, 1714–1837, Introduction,” in Design and the Decorative Arts, Britain 1500–1900, edited by Michael Snodin and John Styles (London: V&A Publications, 2001), p. 183. For a more in-depth discussion of politeness, see Norbert Elias, The Civilizing Process: The Development of Manners, translated by Edmund Jephcott (New York: Urizen Books, 1978). For histories of tea drinking in Britain and America, see William H. Ukers, All about Tea (New York: Tea and Coffee Trade Journal Company, 1935); William H. Ukers, The Romance of Tea: An Outline History of Tea and Tea-Drinking Through Sixteen Hundred Years (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1936); and Rodris Roth, “Tea Drinking in 18th-Century America: Its Etiquette and Equipage,” in Material Life in America, 1600–1860, edited by Robert Blair St. George (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1988), pp. 439–62.

Pennsylvania Gazette, April 18, 1771, item 48630; and May 25, 1769, item 44688.

David S. Shields, Civil Tongues and Polite Letters in British America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1997), pp. 99–140.

Carson, “The Consumer Revolution in British North America: Why Demand?,” pp. 586–92.

Roth, “Tea Drinking in 18th-Century America,” p. 447.

Thornton, Seventeenth-Century Decoration in England, France & Holland, pp. 229–30. See p. 229, fig. 216, for a Javaese laquer tea table mounted on a circa 1680 English base. Also see Bowett, English Furniture, p. 25. London chair maker Thomas Phil sold chairs with sawn cabriole legs, described as “frames of ye newest fashion,” to Edward Dryen of Canons Ashby in Northamptonshire in 1714 (see Nancy E. Richards and Nancy Goyne Evans, New England Furniture at Winterthur: Queen Anne and Chippendale Periods [Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Winterthur Museum, 1997], p. 27). Wallace B. Gusler was the first furniture scholar to suggest that the tea table illustrated in fig. 7 could be by Peter Scott. See Wallace B. Gusler, “The Tea Tables of Eastern Virginia,” Antiques 135, no. 5 (May 1989): 1247. A dining table with related feet reputedly came from Robert Carter’s house Corotomin, which burned in 1729 (the author thanks Luke Beckerdite for this information which is based on Carter family tradition). Bowett, English Furniture, p. 14. Ralph Edwards and Percy Macquoid, The Dictionary of English Furniture from the Middle Ages to the Late Georgian Period, 3 vols. (1924–1927; reprint and rev., London: Barra Books Ltd., 1983), 3:145–54. Ralph Edwards, The Shorter Dictionary of English Furniture from the Middle Ages to the Late Georgian Period (London: Country Life, Ltd., 1964), p. 528. For more on the possible Netherlandish influences on the development of the tilt-top tea table, see Thornton, Seventeenth-Century Decoration in England, France & Holland, p. 230; and Peter Thornton, Authentic Décor: The Domestic Interior, 1720–1920 (New York: Viking, 1984), p. 79, no. 95.

For a succinct discussion of English names for tilt-top tables, see Richards and Evans, New England Furniture at Winterthur, p. 274, nt. 1. For Uriell’s inventory, see card file, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (hereafter cited MESDA), Winston-Salem, North Carolina. E. Milby Burton, Charleston Furniture, 1700–1825 (Narberth, Pa.: Livingston Publishing Company for the Charleston Museum, 1955), p. 49. Jack L. Lindsey, Worldly Goods: The Arts of Early Pennsylvania, 1680–1758 (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1999), p. 151. Among these unusual descriptors, English terms continued to appear in American records through the eighteenth century. The 1767 probate inventory of George Johnson of Fairfax County, Virginia, listed a “Moho Snap Table” valued at £1.1.0 (MESDA card file).

Kevin M. Sweeney, “Furniture and the Domestic Environment in Wethersfield, Connecticut, 1639–1800,” in St. George, ed., Material Life in America, 1600–1860, p. 277. Providence Price Agreement, 1757, Crawford Papers, Rhode Island Historical Society, reprinted in Michael Moses, Master Craftsmen of Newport (Tenafly, N.J.: MMI Americana Press, 1984), p. 357. David L. Barquist, American Tables and Looking Glasses in the Mabel Brady Garvan and Other Collections at Yale University (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Art Gallery, 1992), p. 233.

For early references to tea tables, see David B. Warren, Michael K. Brown, Elizabeth Ann Coleman, and Emily Ballew Neff, American Decorative Arts and Paintings in the Bayou Bend Collection (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press for the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1998), p. 36; and Barquist, American Tables and Looking Glasses, p. 90. The earliest known advertisement for “tea table ketches” appeared in the Pennsylvania Gazette in 1741 (Barquist, American Tables and Looking Glasses, p. 232; and William McPherson Hornor, Jr., Blue Book, Philadelphia Furniture, William Penn to George Washington, [Philadelphia: privately printed, 1935], p. 143).

The tea tables and stand shown in figures 9–11 are illustrated and discussed in Jack Lindsey, Worldly Goods, pp. 150–54, nos. 82, 83, 85, 99. Lindsey dated the earliest table (fig. 9) 1715–1735 and suggested that the faceted base block may be a transitional feature linking it stylistically to the stand (fig. 10) and tea table shown in figure 11. Although his proposal may be correct in this instance, faceted base blocks occur much later on furniture from Newport, Rhode Island. (See Antiques 94, no. 6 [December 1968]: 827; and Richards and Evans, New England Furniture, pp. 278–79, 287–88.) For more on the table illustrated in fig. 12, see Clement E. Conger and Alexandra W. Rollins, Treasures of State: Fine and Decorative Arts in the Diplomatic Reception Rooms of the U.S. Department of State (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1991), p. 81. Gusler, “The Tea Tables of Eastern Virginia,” pp. 1245–46; the example shown in fig. 9 of Gusler’s article is not of the period.

Evidence regarding this type of turning is scant because no seventeenth- or eighteenth-century encyclopedias illustrate the process. Craftsmen probably used a lathe attachment similar to the “Arbor & Cross for Turning Stands,” which survived in the workshop of the Dominy family of cabinetmakers in East Hampton, Long Island (see Charles F. Hummel, With Hammer in Hand [Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press for the Winterthur Museum, 1968], p. 90). Similar to modern day face-plates, the attachment had an iron cross with four holes for screws that engaged the stock. This allowed the workpiece to spin on a vertical plane. Many tabletops have four holes in the undersides measuring equal distances from the center point and from each other (see Patricia E. Kane, “The Palladian Style in Rhode Island Furniture: Fly Tea Tables,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite [Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1999], pp. 14–15, nt. 8). Even tops without such holes may have been turned. Some craftsman may have glued the top to a board that was attached the cross. The author thanks Michael S. Podmaniczky for his insights on these processes.

Glenn Adamson, “The Politics of the Caned Chair,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2002), pp. 175–206. For more on caned chair makers trading chair parts, see Benno Forman, American Seating Furniture, 1630–1730, An Interpretive Catalog (New York: W. W. Norton, 1988), pp. 248–49.

Pennsylvania Gazette, May 30, 1751, item 13033. J. Stewart Johnson, “New York Cabinetmaking prior to the Revolution” (master’s thesis, University of Delaware, 1964), p. 28. Barquist, American Tables and Looking Glasses, pp. 232–23. “The Thomas Elfe Account Book,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 36, no. 2 (April 1936): 57, 61.

Pennsylvania Gazette, December 19, 1771, item 50175. Also see an earlier version of the same advertisement on May 15, 1766, item 37944. The Great River: Art and Society of the Connecticut Valley, 1635–1820, edited by Gerald W. R. Ward and William N. Hosley, Jr. (Hartford, Conn.: Wadsworth Atheneum, 1985), p. 226, nt. 3. For a discussion of how craftsmen negotiated their exchange relationships in individual social economies, see Edward S. Cooke, Jr., Making Furniture in Preindustrial America: The Social Economy of Newtown and Woodbury, Connecticut (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), p. 5. For examples of the relationships between less specialized rural artisans in North Carolina, see John Bivins, Jr., The Furniture of Coastal North Carolina, 1700–1820 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for MESDA, 1985), pp. 60–63.

Helena Hayward and Pat Kirkham, William and John Linnell: Eighteenth-Century London Furniture Makers, 2 vols. (New York: Rizzoli International, 1980), 1:171. Nancy Ann Goyne, “Furniture Craftsmen in Philadelphia, 1760–1780. Their Role in Mercantile Society” (master’s thesis, University of Delaware, 1963), p. 215.

Ward and Hosley eds., The Great River, pp. 225–26. Kane, “The Palladian Style in Rhode Island Furniture,” pp. 7–9. The author thanks Wallace Gusler for this information.

Benno M. Forman, “Delaware Valley ‘Crookt Foot’ and Slat-Back Chairs: The Fussell-Savery Connection,” Winterthur Portfolio 15, no. 1 (spring 1980): 46. For Savery labels, see Hornor, Blue Book, pls. 88–93. Pennsylvania Gazette, September 25, 1755, item 18764.

“The Thomas Elfe Account Book, 1765–1775,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine, 36, no. 2 (April 1935): 57, 61. Luke Beckerdite, “Immigrant Carvers and the Development of the Rococo Style in New York, 1750–70,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1996), pp. 246–47. Luke Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops, Part III: Hercules Courtenay and His School,” Antiques 131, no. 5 (May 1987): 1046. Leroy Graves and Luke Beckerdite, “New Insights on John Cadwalader’s Commode-Seat Side Chairs,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2000), pp. 153–60.

Beckerdite, “Immigrant Carvers,” pp. 249–55.

The author thanks Alan Miller and Luke Beckerdite for the information on the table illustrated in figure 24. Luke Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops, Part II: Bernard and Jugiez,” Antiques 128, no. 9 (September 1985): 505.

John J. McCusker and Russell R. Menard, The Economy of British North America, 1607– 1789 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1985), pp. 60–68, 268–69. Carson, “The Consumer Revolution in British North America: Why Demand?,” p. 617.

Ronald L. Hurst and Jonathan Prown, Southern Furniture 1680–1830, The Colonial Williamsburg Collection (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1997), p. 318. Ronald L. Hurst, “Cabinetmakers and Related Tradesmen in Norfolk, Virginia, 1770–1820” (master’s thesis, College of William and Mary, 1989), pp. 10, 15. Margaretta M. Lovell, “‘Such Furniture as Will Be Most Profitable,’ The Business of Cabinetmaking in Eighteenth-Century Newport,” Winterthur Portfolio 26, no. 1 (spring 1991): 29–30. Hurst discusses the transfer of furniture-making traditions between American cities in “Cabinetmakers and Related Tradesmen in Norfolk,” pp. 19–20. For more about the influence of London commerce and production on the rural Chesapeake, see Lois Green Carr and Lorena S. Walsh, “The Standard of Living in the Colonial Chesapeake,” William and Mary Quarterly 45, no. 1 (January 1988): 139.

Albert Sack, “Regionalism in Early American Tea Tables,” Antiques 131, no. 1 (January 1987): 248–63.

David Hancock, Citizens of the World: London Merchants and Integration of the British Atlantic Community, 1735–1785 (Cambridge, Eng.: Cambridge University Press, 1995). John Bivins, Jr., “A Catalog of Northern Furniture with Southern Provenances,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 15, no. 2 (May 1989): 61. John Bivins, Jr., “Rhode Island Influence in the Work of Two North Carolina Cabinetmakers,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1999), pp. 79–80. For Goodwin’s table, see Brock Jobe and Myrna Kaye, New England Furniture: The Colonial Era (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1984), pp. 298–99.

Kane, “The Palladian Style in Rhode Island Furniture,” pp. 1–2. In England the term “fly table” typically referred to a breakfast table with short leaf supports or “flys” (Christopher Gilbert, The Life and Work of Thomas Chippendale, 2 vols. [New York: Macmillan Publishing, Co., 1978], 1:302). Martha H. Willoughby, “The Accounts of Job Townsend, Jr.,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1999), p. 131.

Jeanne Vibert Sloane, “John Cahoone and the Newport Furniture Industry,” in New England Furniture, Essays in Memory of Benno M. Forman, edited by Brock Jobe (Boston: Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, 1987), pp. 88–112. Lovell, “‘Such Furniture as Will Be Most Profitable,’” pp. 27–62. For more on the desk illustrated in fig. 38, see Luke Beckerdite, “The Early Furniture of Christopher and Job Townsend,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2000), p. 47. Beckerdite argues that many aspects of Newport case design and construction were developed to facilitate the furniture export trade.

McCusker and Menard, The Economy of British North America, p. 102; John J. McCusker, Money and Exchange in Europe and America, 1600–1775, a Handbook (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1978), p. 133. Main, “The Standard of Living in Southern New England,” p. 127. Kerry A. Trask, In the Pursuit of Shadows: Massachusetts Millenialism and the Seven Years War (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1989), pp. 2–3. Kenneth Lockridge, “Land, Population, and the Evolution of New England Society 1630–1790,” Past and Present 39 (April 1968): 68–69.

For a discussion about how some Pennsylvania German communities adopted and adapted Anglo-American designs, see Cynthia G. Falk, “Symbols of Assimilation or Status? The Meanings of Eighteenth-Century Houses in Coventry Township, Chester County, Pennsylvania,” Winterthur Portfolio 33, no. 2/3 (summer 1998): 107–34.

T. H. Breen, “The Meanings of Things: Interpreting the Consumer Economy in the Eighteenth Century,” in Brewer and Porter eds., Consumption and the World of Goods, p. 251.

For further discussion of the growing choices available to eighteenth-century consumers, see Martin, “Makers, Buyers, and Users,” p. 155; and Breen, “‘The Baubles of Britain’: The American and Consumer Revolutions of the Eighteenth Century,” in Carson, Hoffman, and Albert eds., Of Consuming Interests, p. 452; and Breen, “The Meanings of Things,” p. 251.

Jonathan Prown and Richard Miller, “The Rococo, the Grotto, and the Philadelphia High Chest,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1996), p. 108.

For more on Harding, see Luke Beckerdite, “An Identity Crisis: Philadelphia and Baltimore Furniture Styles of the Mid-Eighteenth Century,” in Shaping a National Culture: The Philadelphia Experience, 1750–1800, edited by Catherine E. Hutchins (Winterthur, Del.: Winterthur Museum, 1994), pp. 243–81. For more on furniture carving, see Luke Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops, Part I: James Reynolds,” Antiques 124, no. 5 (May 1984): 1120–33; and Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops, Part II: Bernard and Jugiez,” pp. 498–513; and Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops, Part III: Hercules Courtenay and His School,” pp. 1044–63; and Beckerdite, “Carving Practices in Eighteenth Century Boston,” in New England Furniture: Essays In Memory of Benno M. Forman, pp. 123–62; and Beckerdite, “Immigrant Carvers,” pp. 233–65.

Christie’s, “The Collection of Mr. and Mrs. James L. Britton,” New York, January 16, 1999, lot 592. Prown and Miller, “The Rococo, the Grotto, and the Philadelphia High Chest,” p. 105.

For the Providence price list, see Moses, Master Craftsmen of Newport, p. 357. For the Philadelphia price list, see Martin Eli Weil, “A Cabinetmaker’s Price Book,” American Furniture and Its Makers, edited by Ian M. G. Quimby (Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press for the Winterthur Museum, 1979), p. 187. The 1772 Philadelphia price list only includes mahogany and walnut, but maple was an option available throughout the region.

Weil, “A Cabinetmaker’s Price Book,” p. 187. “The Thomas Elfe Account Book, 1765–1775,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 37, no. 4 (October 1936): 151.

Willoughby, “The Accounts of Job Townsend, Jr.,” pp. 109–61.