Face jug fragment, Miles Mill, Edgefield, South Carolina, ca. 1867–1872. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 5". (All fragments courtesy Georgia Archaeological Institute; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Toby jug, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1785. Pearlware. H. 10". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Face jug, Edgefield, South Carolina, ca. 1860–1870. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 5 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Face jug, Edgefield, South Carolina, ca. 1860–1870. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 6 5/8". (Courtesy, James Witkowski; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Face jug, Edgefield, South Carolina, ca. 1860–1870. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 4 7/8". (Courtesy, Arthur Goldberg; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Nkisi figure, Zaire, Africa, ca. 1900. Canarium schweinfurthii. H. 18 7/8". (Courtesy, Georgia Archaeological Institute; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the nkisi figure illustrated in fig. 6

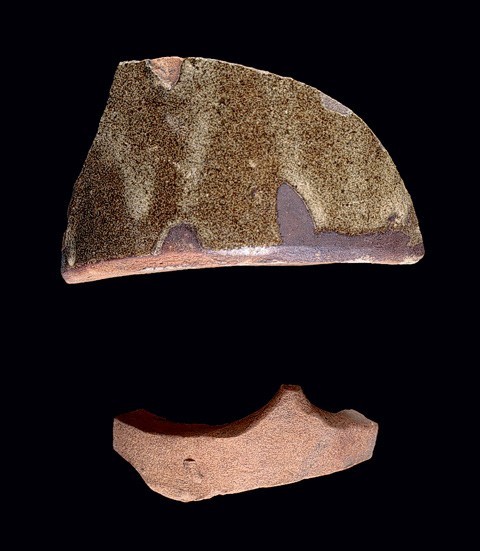

Face jug fragments, Miles Mill, Edgefield, South Carolina, ca. 1867–1872. Alkaline-glazed stoneware.

Face jug fragments, Miles Mill, Edgefield, South Carolina, ca. 1867–1872. Alkaline-glazed stoneware.

Face jug fragments, Miles Mill, Edgefield, South Carolina, ca. 1867–1872. Alkaline-glazed stoneware.

Face jug fragments, Miles Mill, Edgefield, South Carolina, ca. 1867–1872. Alkaline-glazed stoneware.

Face jug neck fragments, Miles Mill, Edgefield, South Carolina, ca. 1867–1872. Alkaline-glazed stoneware.

Face jug fragments, Miles Mill, Edgefield, South Carolina, ca. 1867–1872. Alkaline-glazed stoneware.

Face jug handle fragment, Miles Mill, Edgefield, South Carolina, ca. 1867–1872. Alkaline-glazed stoneware.

Face jug base fragments, Miles Mill, Edgefield, South Carolina, ca. 1870. Alkaline-glazed stoneware.

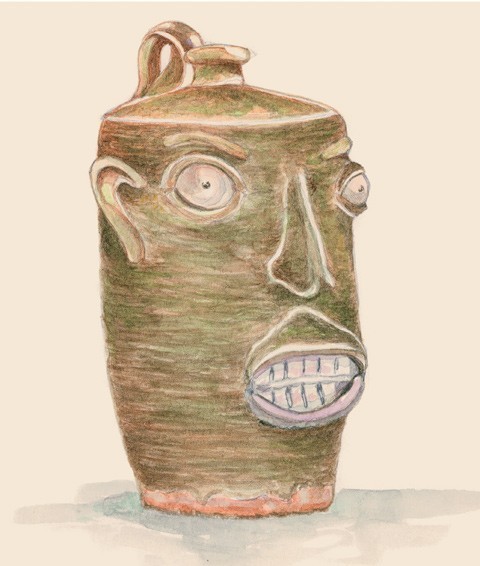

Artist’s reconstruction based on the fragments recovered from the John L. Miles site. (Drawing, Christine Madigan.) The best guess for the shape of the face jug came from an intact storage jug found on the Miles site.

In this sequence of photographs, Peter Lenzo forms the jug on the wheel. First the clay is centered and opened, then a cylinder is raised and the shaping of the body is done. After the body contours are defined, the shoulder and neck are closed to create the jug. The initial finishing of the neck and lip begins at this stage.

In this sequence of photographs, Peter Lenzo forms the jug on the wheel. First the clay is centered and opened, then a cylinder is raised and the shaping of the body is done. After the body contours are defined, the shoulder and neck are closed to create the jug. The initial finishing of the neck and lip begins at this stage.

In this sequence of photographs, Peter Lenzo forms the jug on the wheel. First the clay is centered and opened, then a cylinder is raised and the shaping of the body is done. After the body contours are defined, the shoulder and neck are closed to create the jug. The initial finishing of the neck and lip begins at this stage.

In this sequence of photographs, Peter Lenzo forms the jug on the wheel. First the clay is centered and opened, then a cylinder is raised and the shaping of the body is done. After the body contours are defined, the shoulder and neck are closed to create the jug. The initial finishing of the neck and lip begins at this stage.

In this sequence of photographs, Peter Lenzo forms the jug on the wheel. First the clay is centered and opened, then a cylinder is raised and the shaping of the body is done. After the body contours are defined, the shoulder and neck are closed to create the jug. The initial finishing of the neck and lip begins at this stage.

In this sequence of photographs, Peter Lenzo forms the jug on the wheel. First the clay is centered and opened, then a cylinder is raised and the shaping of the body is done. After the body contours are defined, the shoulder and neck are closed to create the jug. The initial finishing of the neck and lip begins at this stage.

In this sequence of photographs, Peter Lenzo forms the jug on the wheel. First the clay is centered and opened, then a cylinder is raised and the shaping of the body is done. After the body contours are defined, the shoulder and neck are closed to create the jug. The initial finishing of the neck and lip begins at this stage.

In this sequence of photographs, Peter Lenzo forms the jug on the wheel. First the clay is centered and opened, then a cylinder is raised and the shaping of the body is done. After the body contours are defined, the shoulder and neck are closed to create the jug. The initial finishing of the neck and lip begins at this stage.

In this sequence of photographs, Peter Lenzo forms the jug on the wheel. First the clay is centered and opened, then a cylinder is raised and the shaping of the body is done. After the body contours are defined, the shoulder and neck are closed to create the jug. The initial finishing of the neck and lip begins at this stage.

Peter Lenzo finishes the neck and lip of the jug.

The thrown jug body is cut from the wheel head with a wire tool.

A typical method of forming handles is known as “pulling,” whereby the clay is drawn out in successive pulls until the right thickness is achieved. The pulled strip is then cut to size.

The cut handle is attached first to the shoulder and then to the body.

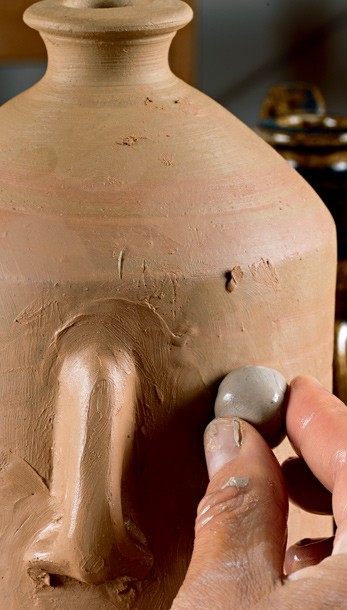

The first facial feature to be placed is the nose, which is attached as a wedge-shaped coil and subsequently modeled by hand.

The first facial feature to be placed is the nose, which is attached as a wedge-shaped coil and subsequently modeled by hand.

The first facial feature to be placed is the nose, which is attached as a wedge-shaped coil and subsequently modeled by hand.

After the nose is formed, two balls of the kaolin that will become the eyes are pressed into position.

After the nose is formed, two balls of the kaolin that will become the eyes are pressed into position.

After the nose is formed, two balls of the kaolin that will become the eyes are pressed into position.

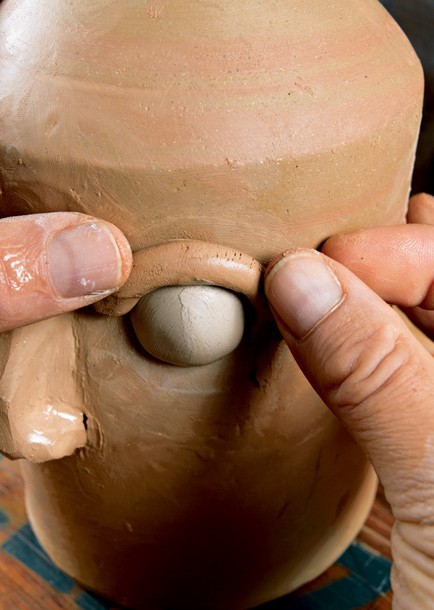

Coils of clay are placed over the top and bottom of the kaolin balls to create the eye sockets. This step is one of the most critical because the shrinkage rate of the two clay bodies differs

Coils of clay are placed over the top and bottom of the kaolin balls to create the eye sockets. This step is one of the most critical because the shrinkage rate of the two clay bodies differs

Coils of clay are placed over the top and bottom of the kaolin balls to create the eye sockets. This step is one of the most critical because the shrinkage rate of the two clay bodies differs

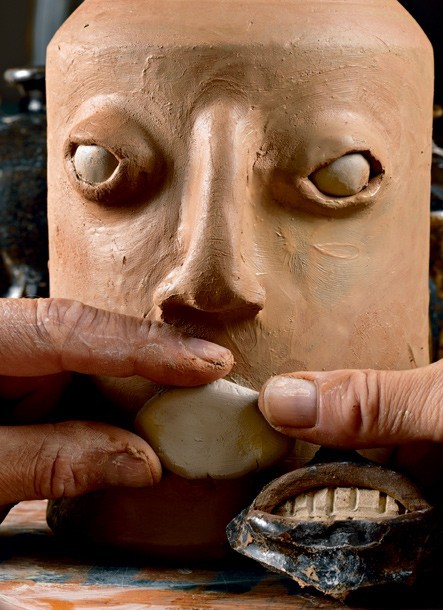

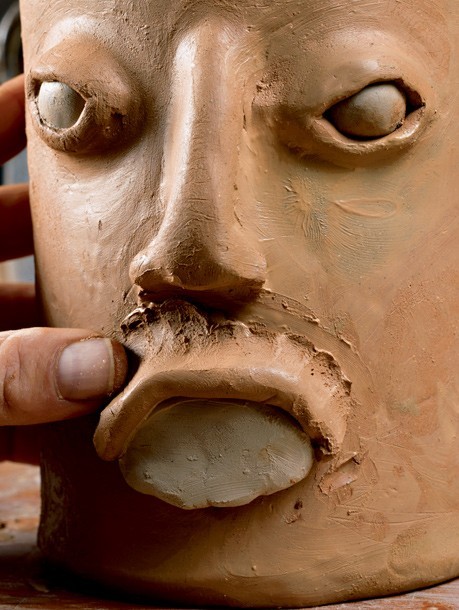

An oval pad of kaolin is prepared and pressed onto the body of the jug. Coils of clay are then placed and modeled to create the lips.

An oval pad of kaolin is prepared and pressed onto the body of the jug. Coils of clay are then placed and modeled to create the lips.

An oval pad of kaolin is prepared and pressed onto the body of the jug. Coils of clay are then placed and modeled to create the lips.

Clay coils are positioned to form the eyebrows, which are modeled with the help of a stick tool.

Clay coils are positioned to form the eyebrows, which are modeled with the help of a stick tool.

An original eye fragment is compared to Lenzo’s prototype.

Clay coils are placed for the ears, which are modeled by hand.

Clay coils are placed for the ears, which are modeled by hand.

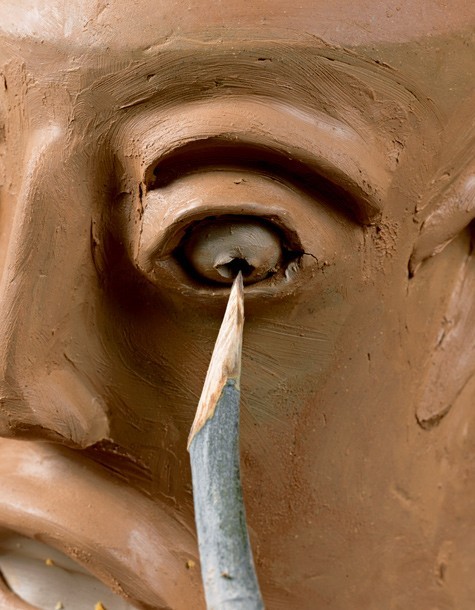

A sharpened stick is used to create the iris. Most of the punctures observed on the fragments were deep and tubular.

The teeth are etched with a stick. Close examination of the fragments reveals that these marks were made after the lips had been applied.

The teeth are etched with a stick. Close examination of the fragments reveals that these marks were made after the lips had been applied.

As clay normally shrinks 10 to 15 percent during drying and firing, the unfired prototype face jug appears larger than the intact storage jug recovered from the site.

One of the demonstration jugs was cut in half to show the interior depressions resulting from the pressure applied when attaching the various facial features. These depressions are an exact match for many of the original sherds.

Melted wax is brushed over the kaolin mouth and eyes. This resist, which prevents the glaze from sticking to the kaolin, will burn off during firing leaving the applied areas white and unglazed. Some type of beeswax is thought to have been used by the Edgefield potters.

Melted wax is brushed over the kaolin mouth and eyes. This resist, which prevents the glaze from sticking to the kaolin, will burn off during firing leaving the applied areas white and unglazed. Some type of beeswax is thought to have been used by the Edgefield potters.

The liquid glaze—a mixture of commercially prepared fine clay, hardwood ash secured from fireplaces and woodstoves, and mined feldspar—is poured into the interior of the jug and allowed to drain. The exterior of the jug is then dipped in the glaze and allowed to air dry. Note how the wax over the eyes and mouth repels the glaze. Many original sherds and vessels exhibit finger marks on the bases of the jugs (see fig. 35). The absence of glaze on the pot’s bottom helps keep them from sticking to the kiln during firing.

The liquid glaze—a mixture of commercially prepared fine clay, hardwood ash secured from fireplaces and woodstoves, and mined feldspar—is poured into the interior of the jug and allowed to drain. The exterior of the jug is then dipped in the glaze and allowed to air dry. Note how the wax over the eyes and mouth repels the glaze. Many original sherds and vessels exhibit finger marks on the bases of the jugs (see fig. 35). The absence of glaze on the pot’s bottom helps keep them from sticking to the kiln during firing.

Face jugs, Peter Lenzo, Columbia, South Carolina, 2006. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 9 1/2". At left is the glazed but unfired face jug. At right is a previously fired example of a jug, shown to illustrate the alkaline glaze color.

Face jug, Miles Mill, Edgefield, South Carolina, ca. 1867–1872. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Charlton Brasher.) Note that the lips and teeth have spalled away on this example at their points of attachment.

Face jug, Miles Mill, Edgefield, South Carolina, ca. 1867–1872. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Charlton Brasher.) Note that the lips and teeth have spalled away on this example at their points of attachment.

Face jug, Miles Mill, Edgefield, South Carolina, ca. 1867–1872. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 5 9/16". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.).

Face jug, Miles Mill, Edgefield, South Carolina, ca. 1867–1872. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 5 9/16". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.).

The First archaeological evidence of nineteenth-century face jug production within South Carolina’s Edgefield District has been announced by the Georgia Archaeological Institute (fig. 1). The production site, located on one of the Miles family potteries near Eureka, sheds light not only on the manufacturing process but also on the origin of some of the vessels in major collections. Study of the recovered fragments proved invaluable, enabling exploration of the technology of face jug production by re-creating several facsimile vessels. This should provide a basis for understanding similar jugs and make it easier to attribute them to specific makers or places.

Origins of Southern Face Vessels

The origin of face vessels made by Southern slaves has been the subject of great debate in recent years.[1] Anthropomorphic representations have appeared on clay pots in virtually all cultures since people first began molding clay. Some researchers claim, perhaps ethnocentrically, that slave-made face jugs got their start with the help of the English Toby jug.[2] The Toby, an eighteenth-century figural vessel most commonly made as a pitcher or decorative piece (fig. 2), was introduced through trade into Africa where it reportedly was adopted and adapted by African artisans. Even a cursory study of African art and religious beliefs, however, would not support such a speculation. Although in 1858 Edgefield saw an influx of slaves from the Congo, the distinct form of the Toby jug, with its traditional tricorn hat and colorful attire, has never been found among the African clay forms of this region. One vessel in the collection of the Charleston Museum, attributed to black potter Jim Lee from Kirksey, South Carolina, is reminiscent of the form—a figural bottle in the shape of a man—but bears no direct morphological connection.[3]

Early American ceramic historian Edwin AtLee Barber interviewed plantation and pottery owner Colonel Davies from Bath, South Carolina. In commenting about the face vessels made circa 1862 by African slave potters, Davies suggested that the slaves had made them “for their own purposes.”[4] Even at that early date the strange objects aroused curiosity. Interest in their origin and function has intensified over the years, particularly since the only known vessels had been in private and museum collections (figs. 3-5).

Some of the face jugs, which functioned as water vessels, were called “monkey” jugs—after monkeyed, a Southern term for the dehydrating effect of summer heat.[5] The functionality of these jugs does not explain the use of staring eyes and gaping mouths, however, nor does it address why most of the early forms were too small to have any obvious purpose.

Colonel Davies hinted at the connection between the jugs and the “aboriginal art of . . . the Dark Continent,” a point further developed by contemporary folklorist John Vlach.[6] Vlach has suggested a direct connection between the face vessels and the nkisi figures of central and western Congo, now Zaire.[7]

The African minkisi (plural for nkisi), also called power figures, are associated with fetishism and ritual magic. Traditionally wooden figures with wide, bright eyes and gaping mouths, they are made up of various components designated for the practice of magic. The nkisi n’kondi, or nail figure, for example, is a ritual figurine carved from a light, cypresslike wood (Canarium schweinfurthii) believed for this purpose to be sacred (fig. 6). By itself the nkisi does not represent a spiritual personality but is a container for one, and it is up to one member of each village, the nganga n’kondi, to make sure that the capture of the appropriate spirit is accomplished. Taking on the role as expert in such rituals, the nganga n’kondi conceals a mixture of minerals, herbs, and other substances inside the nkisi, usually within its protruding belly cavity. The aromatic blend lures curious spirits, or spiritual powers, who are entrapped when the cavity is sealed.[8] Spirits are also attracted by the bright whites of nkisi eyes, which are either painted with white kaolin clay or inset with glass (fig. 7). The early nkisi were made exclusively of kaolin clay, which was regarded as a sacred substance.[9] As with other parallels, the functional features of the nkisi closely match those of the slave-made face jug, an analogy strengthened by evidence that variations of these rituals are still in existence in America.[10]

It is well accepted that slaves in America practiced their religious beliefs in secrecy. In the tradition of their ancestors, some African Americans, especially in rural areas such as modern-day Edgefield County, still maintain a vigorous belief in “root magic,” a fact confirmed by various informants, from local ministers to descendants of slave families.[11]

History of Face Jug Production

The distinctive African-made, green-glazed jug with red clay body and kaolin inserts is thought to date from after 1858, although there is evidence that white potters made face-decorated harvest vessels even earlier. Virginia-born potter Thomas Chandler, for example, made at least one harvest jug at his Shaw Creek site sometime between 1840 and 1857.[12]

The earliest Edgefield face jugs generally have been attributed to potters working in the upper Horse Creek Valley watershed. The Miles Mill pottery is known to have been located in this area, although the actual location of the site discussed in this paper was not known at the time of these attributions. Various extant examples exhibit rich green or brown glazes, high-ridged noses, and eyes and mouths set within separately applied eyelids and lips. The clay bodies fire to a purplish red color, and the eyes and teeth are made of white kaolin clay. These early vessels exhibit two types of teeth construction: sharp and angular, and flat, square teeth etched into a single piece of kaolin.

The tradition of white Southern potters copying the African-style face jug appears to have begun with South Carolina potter Mark Baynham.[13] A recently discovered circa 1900 face jug bearing his stamp (“MARK”) was reported in the 2003 issue of Ceramics in America.[14] The Baynham vessel appears to have been directly modeled on the slave-made versions: the ears and nose are applied, as are the lips and eyelids, and the eyes and teeth are attached directly onto the vessel’s unglazed body. The teeth, which are especially reminiscent of the African-style vessels, and the eyes were left unglazed, implying use of a wax resist (see figs. 31, 32), and an attempt to mimic the African practice. Baynham did not, however, make separate kaolin inserts for each. Like other white potters who followed him, he probably did not consider the detail and extra work necessary, unaware of their possible religious significance.

Discovery of Face Jug Production

Despite the far-ranging interest in these early face jug forms, no archaeological evidence of their manufacture has ever been recorded.[15] An ongoing reassessment by the Georgia Archaeological Institute (GAI) of the Joseph G. Baynham site (38ED221) at Eureka found conclusive proof of early face jug production.[16] During the first few days, GAI encountered evidence that occupation of the Baynham site dated to the 1870s.[17] Furthermore, beneath the Baynham context an earlier pottery was discovered, which had produced wares entirely different from the Baynham wares in body clay, glaze, and style—including a neck style that was known from an existing face jug.

Face jug fragments were first encountered in a test pit selectively located away from the main Baynham context on a wooded slope near a small dam. It was in fact isolated from all other pottery production areas. A two-meter-by-five-meter excavation subsequently revealed a shallow deposit of face jug fragments, bowl fragments, kiln furniture, and kiln debris. Careful testing of the surrounding area indicates that this one spot might have been selected solely for the production of face jugs.

In all, more than two thousand large fragments and small sherds were recovered from the area at depths ranging from 1.18 to 3.93 inches and representing at least seven face jugs (figs. 8-13). The fragments’ neck styles, in combination with the Miles Mill face jugs housed in collections, allow us to develop a tentative chronology for their manufacture. The earliest appear to be those with double-collared necks, a style found on the lowest levels of the Sunnybrook site, a mile from the Baynham site on Horse Creek. It is believed that this dates to the earliest Lewis Miles occupation of the site, from the 1850s to circa 1867. Stratigraphic evidence enables us to date with some confidence the flat-lipped neck style (see fig. 10) to about 1867–1872, the John L. Miles occupation of both the Baynham and Sunnybrook sites. This same neck type appears on a Davies pottery vessel dated to circa 1862.[18] The similarity of neck styles is attributed to the movement of the upper Horse Creek slave potters from one local pottery to another. The tubular Bodie-style neck appears to be the last of its kind and is documented on Baynham-made dispensary jugs of the early 1880s.[19]

Experimental Production of a Face Jug

Following initial development of the construction sequence and the techniques based on analysis of the recovered sherds it was decided that an experimental reconstruction project might shed further light on the process (fig. 14).[20] Peter Lenzo, a potter in Columbia, South Carolina, was enlisted to reproduce the GAI finds. Lenzo, who maintains a studio on Rosewood Avenue, has gained national recognition for his explorative work and interpretation of the American face jug tradition.

The initial task was to select a local clay for the trial pieces, and Bethune clay from a mine east of Columbia was chosen. The clay was used for the last vessels produced by an early-twentieth-century pottery once owned by Thomas Daugherty, a former partner of Horace Baynham at the Edgefield District pottery at the head of School House Creek.[21] He used a mixture of Bethune clay and Otis Norris’s clay, which Otis digs from around McBee, South Carolina, near the Lynches River. Bethune clay fires to a red color and has a more aggressive tooth (a coarser, stronger body) than Edgefield’s Horse Creek clays, but it was deemed acceptable for the project since the latter was unavailable. Lenzo also experimented with a variety of iron-bearing glaze formulas with the hope of reproducing the rich green glaze the original potters applied over the dark red and purplish fired clay body.

After careful study of the sherds, vessel production began with the throwing of a jug on the wheel (fig. 15). In the absence of a readily identifiable antique prototype, an intact jug recovered from the site that had similar handle and neck characteristics as the face jug sherds was used as a model. The distinctive broad flat lip at the opening of the face jug is unique in the Edgefield tradition and specific to the John L. Miles pottery (fig. 16). After removing the thrown jug from the wheel (fig. 17), a handle was pulled and attached in the manner suggested by the recovered artifacts (figs. 18, 19).

While the jug was still in a wet, plastic state, work began on the various facial components, beginning with the nose. While there is no direct evidence of sequence, starting with the nose helped set up the proportions and balance of the final face. Created from a cone-shaped section of clay, the nose was attached to the vessel’s center and subsequently modeled (fig. 20). It is not known whether these attachments were scored and moistened with water or slip, in keeping with modern hand-building techniques. None of the recovered fragments bears any evidence of scoring. It is clear that considerable force was used to ensure the reliability of the attachment (see fig. 30).

The flat, oval eyes—the vessel’s focal point—were achieved by rolling and pressing small balls of kaolin-based white clay in the palm of the hand. Probably mixed with a binding and fluxing agent, each eye was attached to the jug without any application of slip between it and the vessel’s surface (fig. 21). Small strips of clay rolled on a flat surface into a coil measuring .12 inches in diameter formed the eyelids. Sections of the coil were placed over the eye’s top (fig. 22) and bottom edges and then carefully smoothed.

As with the eyes, the teeth were created from a ball of kaolin-based clay that was rolled and flattened into an oval plate and pressed onto the surface of the jug above the vessel base (fig. 23). Since the kaolin clay has a much higher shrinkage rate during firing than the body clay, potters had to use enough overlapping clay for the eyelids and lips to ensure that neither the eyes nor the teeth fell out. Many of the recovered fragments and related antique face jugs indicate that the kaolin eyes shrank in the firing and moved unnervingly within their sockets. None of the recovered fragments, however, exhibited loose teeth.

Adding a somewhat quizzical expression to the face, coils of clay were used to fashion eyebrows—modeled with a wooden tool (fig. 24)—and ears (fig. 26).

Once the facial features had been attached and modeled, attention was turned to the details. To simulate the iris (fig. 27), a sharp stick was used to create a small, triangular hole in each eye. In most of the recovered eyes, the hole was a deep tubular piercing, probably made with an instrument of uniform width. An object that had a worked edge, possibly a wooden rib, scored the clay to make straight, square teeth but only after two coils of clay had formed the lips (fig. 28).

After the vessel was thoroughly air-dried (fig. 29), preparation for glazing began with the application of wax to the eyes and teeth. This resist technique—the Edgefield potters probably used an application of beeswax—was employed to ensure that the eyes and teeth were left unglazed (fig. 31), and also might have allowed the teeth and eyes to move slightly. The intention, however, is unknown. There is some indication from Edgefield County sources that the effect may have been desirable—that is, the “best” face jugs had eyes that rolled and teeth that chattered.

The final step before firing was coating the interior of the jug and then the exterior in a glaze mixture of a clay slip, wood ash, and possibly some iron (figs. 32, 33).

After the experimental phase of the project had been completed, two antique examples of the face jugs discussed herein came to light. The first was illustrated in the arts section of the New York Times during “Antique Week,” January 2006 (fig. 34). The jug’s overall shape and facial features corresponded very closely with the experimental reconstruction, with the exception of its height. The antique example suggested that some of the face jugs were slightly squatter. A subsequent example confirmed this shape as being more typical of the production on the site (fig. 35).

Undoubtedly, more face jug examples residing in antique collections can now be firmly attributed to the Miles Mill production site. A full report on the face jug find is due to be published by GAI late in 2006.

See John A. Burrison, Fluid Vessel: Journey of the Jug, pp. 92–121 of this volume.

Cinda K. Baldwin, Great and Noble Jar: Traditional Stoneware of South Carolina (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1993), p. 81.

Ibid., pp. 83–84, figs. 3.11, 3.12.

Edwin AtLee Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States: An Historical Review of American Ceramic Art from the Earliest Times to the Present Day (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1909), p. 466.

John Michael Vlach, The Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1990), pp. 86–90.

Barber, Pottery and Porcelain of the United States.

Vlach, Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts; Mark M. Newell, “Echoes of Africa,” GAI Research Manuscript 433/1966, which covers 1996 iconographic research in Zaire.

Robert Farris Thompson, “The Grand Detroit N’Kondi,” Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of the Arts 56, no. 4 (1978): 207–22.

Denba Saccoh, Zaire, personal communication, 1996.

Personal communication with an African-American minister in Edgefield, who wishes to remain anonymous.

A highly sensitive topic among rural blacks, root magic is a continuing research interest of the Georgia Archaeological Institute. Much of the sensitivity and secrecy are connected directly with the power attributed to the grave sites of important blacks of the past one hundred and fifty years.

Baldwin, Great and Noble Jar, pp. 47, 51–54.

Nancy Baynham, Baynham: A History of a South Carolinian Family (Augusta, Ga.: Hamburg Press, 1999).

Mark M. Newell, “Making His “MARK,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2003), pp. 273–75.

Stephen Ferrell, an avocational Edgefield potter-historian, found two face-vessel fragments in the 1980s while raking through a waster pile at Sunnybrook, one of the Lewis Miles sites.

George J. Castille, Cinda K. Baldwin, and Carl Steen, Archaeological Survey of Alkaline-Glazed Pottery Kiln Sites in Old Edgefield District, South Carolina ([Columbia, S.C.]: McKissick Museum, 1988). Researchers on this site in the 1980s published findings to the eVect that Baynham had not been a part of the Edgefield stoneware tradition but that his pottery operation represented a cultural intrusion from Ohio in 1900. GAI’s preliminary survey of the site in 1996 also determined that the two sites extended over a far greater area than the earlier archaeologists had supposed—1.5 miles in length as opposed to the 328 feet originally reported. The GAI’s reassessment discovered that the boundaries of the site, which previously had been described as encompassed within a few hundred feet, in fact extend beyond a 1.5-by-.5-mile strip.

Mark M. Newell, “A Spectacular Find at the Joseph Gregory Baynham Pottery Site,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 229–32.

Making Faces: Southern Face Vessels 1840–1990, exh. cat. ([Columbia, S.C.]: McKissick Museum, 2001), p. 17.

Baldwin, Great and Noble Jar, p. 103. By 1870 the J. P. Bodie pottery was in operation at Kirksey’s Crossroads in the Edgefield District.

A grant from the Chipstone Foundation funded the cost of materials and documentation.

Baldwin, Great and Noble Jar, p. 141