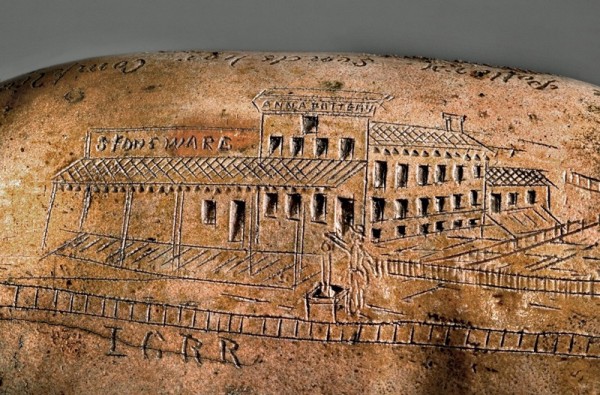

Pig flask, Anna Pottery, (act. 1859–1896), Anna, Illinois, ca. 1865. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 3 1/2", L. 8". (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

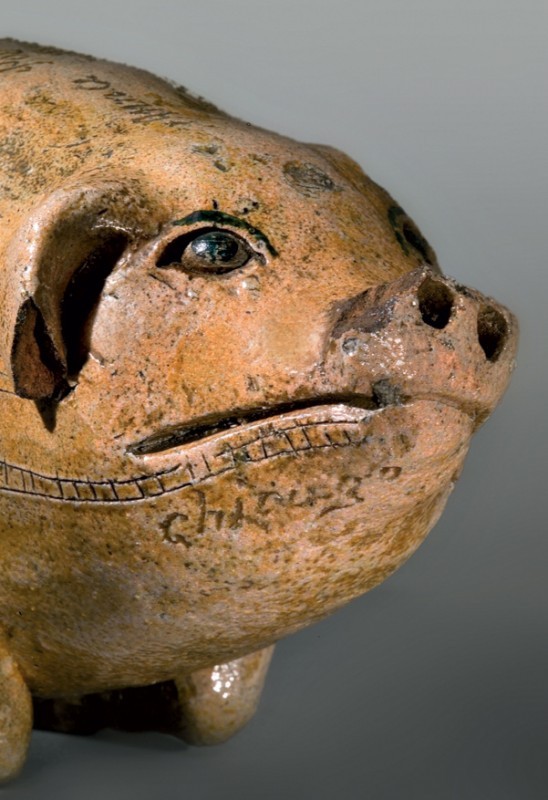

Detail of the Anna Pottery inscription on the pig flask illustrated in fig. 1.

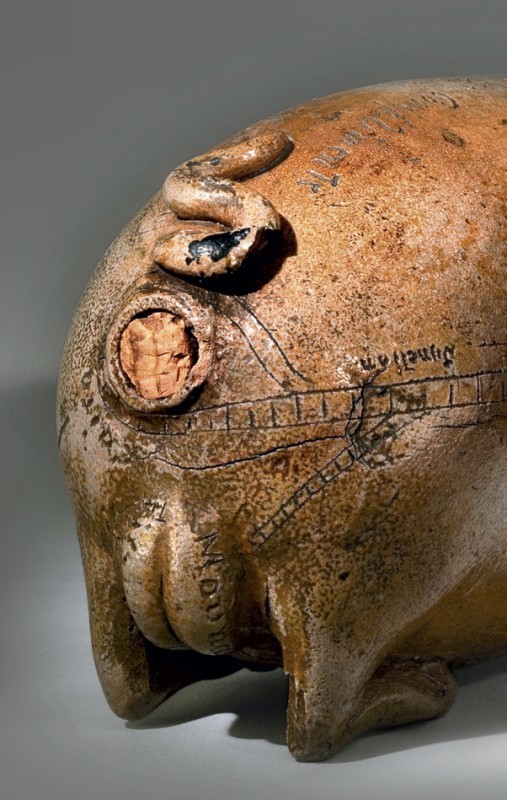

Detail of the painted eyes on the pig flask illustrated in fig. 1.

Detail of the underside of the pig flask illustrated in fig. 1.

View of the inscription on the reverse side of the pig flask illustrated in fig. 1.

Detail of the flask opening on the pig flask illustrated in fig. 1.

Founded in 1859 in the newly incorporated town of Anna in southern Illinois by brothers Cornwall Kirkpatrick (1814–1890) and Wallace Kirkpatrick (1828–1896), the Anna Pottery primarily produced utilitarian stoneware.[1] Unlike many contemporary pottery owners, the Kirkpatricks were working potters as well as businessmen. While their employees threw crocks, jugs, milk pans, reed-stem tobacco pipes, and other functional wares, the brothers fashioned creative pieces.[2] Cornwall was primarily interested in incised decoration and Wallace in modeling, although they overlapped occasionally in their artistic pursuits.[3] Today the Anna Pottery is associated with fanciful wares such as sculptural delirium tremens whiskey jugs, vessels with allover incised decoration, and flasks in the shape of pigs, the most common of the imaginative wares they created.[4]

In 2005 Colonial Williamsburg had the good fortune to acquire an Anna Pottery pig flask for the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Collection (fig. 1).[5] The pottery made thousands of hand-thrown and -modeled flasks in the shape of pigs. They were often commissioned by businesses—saloons, railroad companies, and glass and china merchants—for distribution to their customers as premiums or as advertising.[6] Some, like Colonial Williamsburg’s example, were given by the Kirkpatricks as presentation pieces to specific individuals. On one side of Williamsburg’s flask is an incised personalized inscription and on the other is an image of the pottery itself (fig. 2). While there are a handful of surviving pieces from the Anna Pottery that are decorated in this way, this is the only known pig flask to include this ornamentation. The pottery building is shown with the “Anna Pottery” sign at the top and another sign to the left advertising “stoneware.” Even a well located across the street is visible, as are the tracks of the Illinois Central Railroad (ICRR) running past the pottery.[7] Lines representing the routes of railroads were commonly incised into the pigs, and this piece is no exception. The stops included on this flask are Chicago, Cairo, Mound City (home of the recipient of this piece), and Porkokolis, a name often given to Cincinnati. Finally, the Williamsburg pig is exceptional in its ornamentation with cold painted decoration on its eyes and penis (figs. 3, 4).

The inscription on the reserve side of the flask reads: “Anna Pottery sends her compliments to Howard editor of the Mound City Journal, and clerk of the city council. Please accept this token of regard with a little good old Bourbon in a hogs. . .” (fig. 5). The message ends near the rear of the animal, and the flask opening is its anus (fig. 6). Some variation of the second half of this inscription can be found on most of the surviving Anna pigs. The intention of such inscriptions has been debated. Some contend the flasks were meant to deter drinking, as imbibing from the anus of a pig would remind people that consuming alcohol is a dirty endeavor and to be avoided. An alternative interpretation suggests the words were intended to be a humorous and ironic juxtaposition. Advocates of the latter theory believe the Kirkpatricks were social liberals who did not support the growing temperance movement.[8]

Hiram Reese Howard, to whom this flask was presented, may have known the Kirkpatricks; they were all members of the Masons, although not of the same lodge. It is also possible Howard was active in the Republican Party and met the brothers in that capacity.[9] Whatever their relationship, Hiram Howard was given this pig flask while he was “editor of the Mound City Journal”—a publication founded in 1864. It is unclear when Howard became editor of the journal, but that was certainly his position in April 1865 when, according to family tradition, he wrote an editorial for the paper about the assassination of President Lincoln. That same year he was listed as publisher on the masthead of the September 28 issue.[10] Sometime between September 28, 1865, and January 16, 1866, Hiram Howard left Mound City for Point Pleasant, West Virginia, where he married Nannie A. Rogers.[11] Given the inscription, Howard had to have been presented with the flask between 1864 and early January 1866. Whether it was bestowed as a parting gift or at some earlier date, it could not have been fashioned any later than January 16, 1866, thus making it the earliest known Anna Pottery pig flask.[12] After Hiram Howard’s death on May 9, 1912, it passed to his daughter, Helen Howard Williams, and later to her daughter Helen Williams Pressley.

Whether the original intentions of the Kirkpatrick brothers were to inspire amusement with their flasks or to promote temperance, it is clear that this particular piece stimulated laughter. Hiram Howard’s granddaughter, Helen Pressley, recalled that this pig flask was sent back and forth between family members for more than one hundred years, accompanied by rhymed verse describing the pig’s anatomical attributes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank Ellen Denker, Robert Hunter, Richard Mohr, and Susan Shames for their assistance. I would also like to thank Janine Skerry, Curator of Ceramics and Glass at Colonial Williamsburg, for her support and encouragement.

Suzanne Findlen Hood, Assistant Curator of Ceramics and Glass,

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; shood@cwf.org

Ellen Paul Denker, The Kirkpatricks’ Pottery at Anna, Illinois (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986), pp. 5–6.

Ibid., p. 12.

Richard D. Mohr, Pottery, Politics, Art: George Ohr and the Brothers Kirkpatrick (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003), pp. 15–16.

Published examples of the Kirkpatricks’ fanciful wares can be found in Ellen Paul Denker, “Forever Getting up Something New”: The Kirkpatricks’ Pottery at Anna, Illinois 1859–1896 (master’s thesis, University of Delaware, 1978); Denker, The Kirkpatricks’ Pottery; Mohr, Pottery, Politics, Art; and Richard D. Mohr, “Stonewares Light and Dark: The Nature and Importance of the Kirkpatricks’ Anna Pottery,” Folk Art 32 (Fall 2007): 70–81.

Two other Anna Pottery pieces are in the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Collection at Colonial Williamsburg: a delirium tremens whiskey jug entitled “In Side Out” (1976.900.5); and a “Little Brown Jug” (1975.900.5).

Denker, The Kirkpatricks’ Pottery, p. 16; Mohr, Pottery, Politics, Art, p. 188.

Denker, The Kirkpatricks’ Pottery, p. 13.

There has been considerable debate among scholars over whether Cornwall and Wallace Kirkpatrick were supporters of the temperance movement or very much against it. For detailed accounts of both arguments, see Denker, The Kirkpatricks’ Pottery; and Mohr, Pottery, Politics, Art.

During the nineteenth century the Republican Party was associated with liberalism and the Democrats with social conservatism. Cornwall and Wallace Kirkpatrick were members of the Republican Party. It is unclear which party Hiram Howard was affiliated with, but he had served in the Union Army and was involved in local politics. Mohr, Pottery, Politics, Art, p. 19; Denker, The Kirkpatricks’ Pottery, pp. 9–10; Hiram Howard’s obituary, Mountaineer, May 17, 1912.

The WorldCat catalog entry for The Mound City Journal, a weekly publication, is based on the issue of September 28, 1865 (vol. 1, no. 46). The most complete run of the paper is held by the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, Springfield, Illinois.

West Virginia Marriage Records, 1863–1900, West Virginia State Vital Statistics Office, Charleston, W.Va.

The earliest published examples of pig flasks date to 1868–1869. See Mohr, Pottery, Politics, Art, p. 15.