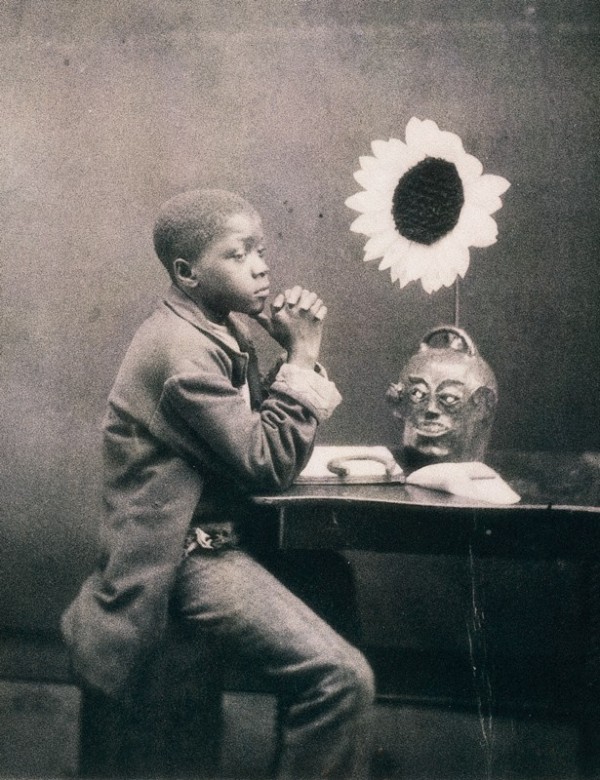

An Aesthetic Darkey, from a series of stereoscopic cards by photographer J. A. Palmer of Aiken, South Carolina, 1882. (Courtesy, J. Garrison Stradling.)

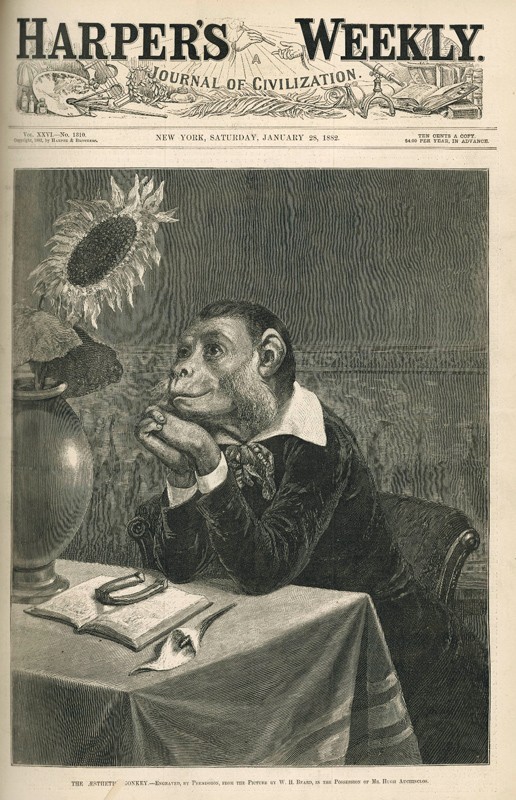

The Aesthetic Monkey, W. H. Beard, 1882. (Courtesy, Wisconsin Historical Society, whs-91892.) This image is a harsh, and possibly homophobic, visual satire of British writer and cultural commentator Oscar Wilde, who embarked on his North American tour in 1882.

Face jug, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1860–1870. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 7". (Courtesy, April Hynes; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Plumber Robert Strang discovered this jug in the 1950s in the Germantown section of Philadelphia, while digging a trench for the foundation and plumbing of the soon-to-be-built Leeds Middle School. The jug was buried at the site of a house that belonged to Leroy Stockton Wingate, who had two live-in servants from the Edgefield District. According to the 1930 U.S. Census, Lewis Gardner was Wingate’s chauffeur and Lewis’s wife, Leatha, was his cook. A World War I draft card for Lewis Gardner states that he was born in Edgefield. Genealogical records indicate that the Gardners’ ancestors were slaves at the plantation of Colonel Thomas J. Davies, a pottery owner interviewed by Edwin Atlee Barber in 1909. “Thomas Jones Davies Bible Records Transcription,” Thomas Jones Davies Bible Records, available online at http://digital.tcl.sc.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/davies/id/75/show/63/rec/19 (accessed March 12, 2013).

Face jug, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1860–1880. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 5 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Initially made by slaves and later by free African-Americans, early Edgefield face vessels are wheel-turned from stoneware clay and fired with alkaline glazes that range in color from sandy brown to olive green. The most distinctive feature of these objects is their highly expressive, applied face, which typically includes wide-open eyes, mouths with bared teeth, and idiosyncratic ears, noses, and eyebrows. On the earliest forms, the eyes and teeth are made from white kaolin clay, often left unglazed. Art historian Robert Farris Thompson notes that “the white . . . eyes and teeth, set against the glaze, make the finest Afro-Carolinian face vessels appear to roar where works three times their size merely whisper. . . . [N]othing in Europe [is] remotely like them, for the use of kaolin insets into the body seem[s] peculiar to the Afro-Carolinian and his imitators.” Robert Farris Thompson, “African Influence on the Art of the United States,” in William R. Ferris, ed., Afro-American Folk Art and Crafts (Boston: G. K. Hall, 1983), p. 39.

Face cup, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1860. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 4 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Face jug, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1860–1880. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 6". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Power figure (nkisi nkondi), Vili, Republic of the Congo, early- to mid-nineteenth century. Wood, metal, glass, fabric, fiber, cowrie shell, bone, leather, gourd, and feather. H. 28 1/4". (Courtesy, Ada Turnbull Hettle Endowment, 1998.502, The Art Institute of Chicago; photo © The Art Institute of Chicago.)

Postcard of a Kongo village with three minkisi (sing. nkisi) in foreground. Reproduced from Hans-Joachim Koloss, ed., Africa: Art and Culture (Munich: Prestel for the Ethnological Museum, Berlin, 2002), p. 126.

Photograph of a man sitting on a mat with a variety of minkisi. The image is stamped “Congo France” and dated October 20, 1909. Reproduced from Raoul Lehuard, Art BaKongo: Les centres de style, 2 vols. (Arounville, France: Arts d’Afrique Noire, 1989), 1: 81.

Power figure, Democratic Republic of the Congo. (Private collection; photo, Marc Felix.) The kaolin on this figure signifies the white skin of the dead.

Toby jug, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1785. Pearlware. H. 10". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Kongo terracotta head. (Courtesy, Royal Museum of Central Africa, Tervuren, Belgium, EO.1949.1.18; photo, J. Van de Vyver, © RMCA Tervuren.)

Face jug, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1860–1880. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 7 1/8". (Courtesy, New York Historical Society, 1937.141.)

Face jug, Lanier Meaders (American, 1917–1998), 1987. Glazed low-fired stoneware. H. 10". (Courtesy, Milwaukee Art Museum, Gift of Ruth and Robert Vogele, M2000.84.)

Face pitcher, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1860–1880. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, David B. Ward; photo, Jim Wildeman.)

Face jug, Thomas Chandler, Edgefield District, South Carolina, ca. 1850. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 11". (Private collection; photo, McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina.)

Two-face monkey-form jug, attributed to Henry Remmey Jr. or his son Richard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1858. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 11". (Ex-collection of Tony and Marie Shank; photo, Tony Shank.)

“Place where the pots of the deceased are kept,” photographed by Friedrich August Louis Ramseyer, Ghana, 1888–1908. 4 3/4 x 6 1/2". (Basel Mission Archives D-30.23.022; www.bmarchives.org/items/show/57131; photo, courtesy Basel Mission Archives.)

Ewe terracotta pots. Reproduced from Karl-Ferdinand Schaedler, Earth and Ore: 2500 Years of African Art in Terra-cotta and Metal (Eurasburg, Germany: Panterra Verlag, 1997), p. 191.

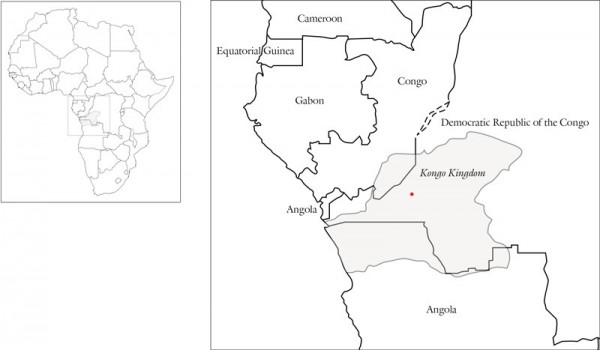

Map of Africa. Area in gray showing the Kingdom of Kongo, ca. 1850. Red dot indicates Madimba in the valley of the Mbidizi River in the Kongo Kingdom. (Map by Wynne Patterson.)

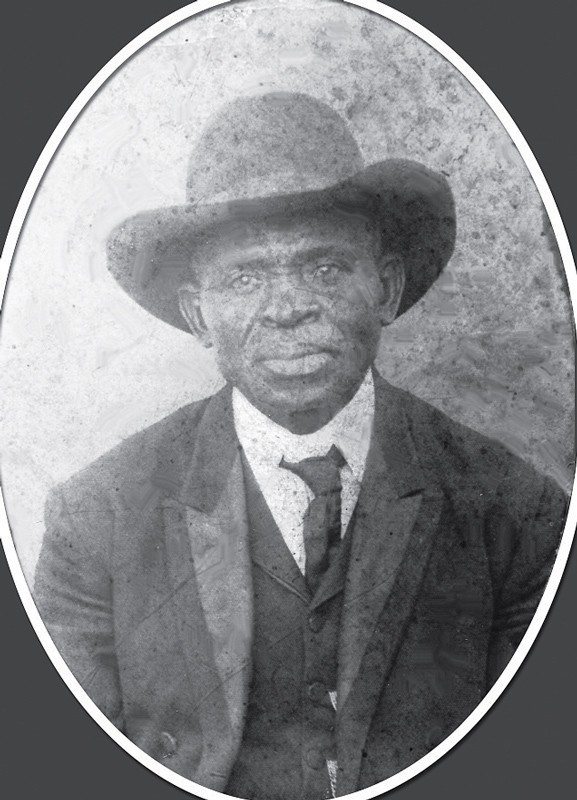

Photograph of Ward Lee, Edgefield County, South Carolina, ca. 1900. (Courtesy, Lee family.)

Face jug attributed to Ward Lee, Edgefield District, South Carolina, ca. 1880. Unglazed stoneware. H. 5". (Courtesy, Georgia Archeological Institute.)

Photographs showing the front and right side of the Romeo Thomas House, Edgefield District, 1908. Reproduced from Charles J. Montgomery, “Survivors from the Cargo of the Negro Slave Yacht Wanderer,” American Anthropologist, n.s., 10, no. 4 (1908): between pages 616–17 and 618–19.

“Catholic Priest Burning Idol House, Sogno, Kingdom of Kongo, 1740s,” reproduced from Paola Collo and Silvia Benso, eds., Sogno: Bamba, Pemba, Ovando . . . (Milan: Franco Maria Ricci, 1986), p. 163. (Photo, courtesy Biblioteca Civica Centrale di Torino.)

Diboondo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, ca. 1800. Terracotta. H. 17 11/16". (Courtesy National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, purchased with funds provided by the Smithsonian Collections Acquisition Program, 89-13-7; photo, Franko Khoury.)

Male and female divination figures, Baule, Côte d’Ivoire, nineteenth or early twentieth century. Wood, pigments, beads, and iron. H. of male 21 7/8"; H. of female 2 5/8". (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Gift of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1969, 1978.412.390, .391.)

Nkisi nkonde with tongue, Lekela Kongo (Yombe), Democratic Republic of Congo, 1913(?). (Courtesy, Coll. G. Rosselli-Lorenzini, Museo Nazionale Preistorico Etnografico “Luigi Pigorini,” inv. 84205; photo © S-MNPE “L. Pigorini” Roma EUR, courtesy MiBAC.)

Face jug, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1860–1880. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 4 1/2". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Jim Wildeman.)

Entry from 1900 U.S. Census, Schultz Township, Aiken, South Carolina.

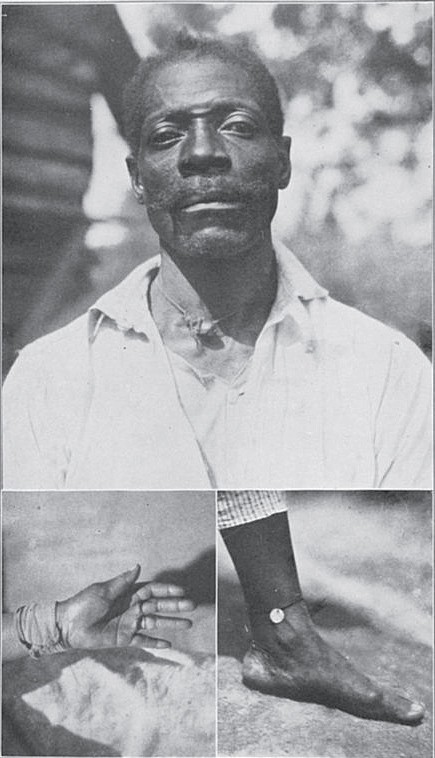

“Nutmeg, red flannel and silver,” in Newbell Niles Puckett, Folk Beliefs of the Southern Negro (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1926), between pp. 314–15. (Courtesy, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture / General Research and Reference Division.)

Face jug, Edgefield District, South Carolina, 1860–1880. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 6 5/8". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the inscription on the back of the face jug illustrated in fig. 31.

When my paw, ‘Obie’ wuz a courtin, a nigger put a spell on him kaise he was a wantin’ my maw too. De nigger got a conjure bag and drapped it in de spring what my paw drunk water from. He wuz laid up on a bed o’ rheumatiz fer six weeks. . . . His brother . . . went to another old conjure man and axed him to take dat spell off’n paw. De conjure man lowed to paw’s brother dat a grapevine growed over de spring, and fer hem to go dar and cut a piece of it six feet long and fetch it to his house at night. When he tuck it to de conjure man’s house, de conjure man . . . took de vine in a dark place and done somethin to it—de lawd knows what. Den he tole my paw’s brother to take it home and give it to paw.[1]

In 1882 J. A. Palmer, an Irish photographer who settled in Aiken, South Carolina, took a provocative photograph that he titled An Aesthetic Darkey (fig. 1).[2] Staged in the manner of historical portraiture, this image features a pensive African-American youth sitting with his elbows resting on a table, a book held open by a horseshoe and a calla lily, and a large sunflower protruding from a face jug.[3] Palmer’s composition was inspired by the cover of the January 28, 1882, issue of Harper’s Weekly, which featured an engraving of William Holbrook Beard’s painting The Aesthetic Monkey (fig. 2).[4] In an overtly racist gesture, Palmer substituted an African-American for Beard’s monkey and replaced his vase with a face jug.

As a late-nineteenth-century resident of Aiken, which was part of the old Edgefield District, Palmer would have known that face vessels were locally made products, but it is doubtful that he had any nuanced understanding of their meaning and use. Indeed, contemporaneous perceptions of these idiosyncratic southern pottery forms varied from community to community and from person to person. Within the white community, face vessels were seen as stylized, and often mocking, representations of African-Americans. Some owners may have even equated the production of these forms with enslaved African-American makers, who worked in Edgefield potteries. But for many of those potters, and members of their community, the distinctive face vessels were ritualistic objects used in the practice of African cultural and religious beliefs. Recent research, including the discovery of face jugs that belonged to or descended in the families of African-Americans from the Edgefield District, has established a link between those pieces and African-American craftsmen (fig. 3), one of whom arrived from the Kongo in 1858. Yet this essay does not purport to establish who introduced the face-vessel tradition to the African-American community in Edgefield. The empowerment of seemingly inanimate objects and the interconnectedness between the human world and the spirit world is the most important concept underlying this essay’s revised interpretation of Edgefield face jugs.

Historiography

In the 1909 edition of The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States, Edwin Atlee Barber recounted his conversations with South Carolina, planter Colonel Thomas Davies.[5] The latter owned the Palmetto Fire Brick Works, a pottery in the town of Bath, then part of the Old Edgefield District. Davies recalled that in 1862 local slaves made “homely designs in coarse pottery” including “weird-looking water jugs, roughly modeled on the front in the form of a grotesque human face,—evidently intended to portray the African features” (figs. 4-6). He also noted that face vessels were not made in secret and that the white population in nineteenth-century South Carolina derisively regarded them as having African precedents:

These curious objects, which I have seen in several collections, labelled “Native Pottery made in Africa,” possess considerable interest as representing an art of the Southern negroes, uninfluenced by civilization, and we can readily believe that the modelling reveals a trace of aboriginal art as formerly practised by the ancestors of the makers in the Dark Continent.[6]

Aside from Barber’s interview, nothing of substance was published on Edgefield face jugs until the early 1980s, when they captured the attention of Robert Farris Thompson, a prominent art historian at Yale University and an authority on Yoruba art and the African diaspora. In his book The Four Moments of the Sun: Kongo Art in Two Worlds and essay “African Influence on the Art of the United States,” Thompson cautioned readers not to ignore the distinctive cultural context in which the makers of face vessels worked or the possibility that African traditions influenced their work—an oversight that continues to constrict a fuller understanding of those ceramic forms. He described the potteries’ dependence on slave labor, pointing out that African-Americans were responsible for much of Edgefield’s production, and attributed face vessels to three anonymous potters: the Master of the Davies Pottery; the Master of the Diagonal Teeth; and the Master of the Louis Miles Pottery. In sum, early Edgefield face vessels were not the creation of a single potter but rather an artistic concept based on a shared background and belief system among certain makers and users.

Much of Thompson’s work centered on slave potters that originally came from the Kingdom of Kongo (Democratic Republic of Congo, Congo-Brazzaville, and Angola) and on visual relationships between Edgefield face jugs and Bakongo wooden figures, which were often made with additional materials including different clays, mirror fragments, and cowrie shells, and, in the case of certain forms, augmented with nails, bones, teeth, bells, and other objects applied during the course of use (figs. 7-8).[7] Thompson noted that the use of kaolin to make the eyes of Edgefield vessels white relates to the ancient northern-Kongo practice of “inserting porcelain fragments within the eye sockets of carved human figures”[8] as well as to West African figural carvings, which occasionally have cowrie shells representing eyes. The use of white or reflective materials in that context facilitated and reflected spiritual possession, what Thompson describes as the “flash of the spirit”:

The vital spark or soul within the spirit-embodying medicine may be, according to the Bakongo, an ancestor come back from the dead to serve the owner of the charm, or a victim of witchcraft, captured in the charm by its owner and forced to do its bidding for the good of the community (if the owner is generous or responsible) or for selfish ends (if he is not).[9]

One class of object Thompson singled out for comparison with Edgefield face jugs are minkisi (zinkisi south of the Kingdom of the Kongo; sing. nkisi), horns, shells, gourds, bundles, ceramic vessels, figures, or other objects infused with the powers of dead spirits (fig. 9). Kaolin and red ochre were important in the composition of some minkisi since the white color of kaolin was associated with the dead (fig. 10) and red ochre was associated with “blood and danger because the dead have the power to both afflict and cure the living.”[10] About 1900, Mu-Kongo Nsemi Ikaki defined a nkisi as:

[t]he name of the thing we use to help a person when that person is sick and from which we obtain health; the name refers to leaves and medicines combined together. . . . Thus an nkisi is also something that hunts down illness and chases it away from the body. An nkisi is also a chosen companion, in whom all people find confidence. It is a hiding place for people’s souls, to keep and compose in order to preserve life.[11]

Nkondi minkisi, which are among the known variety in the West, are wood figures, usually male, with a hollow stomach in which the magical items were placed. These figures, as well as other forms of nkisi, were owned and operated by nganga, who had the power to activate a nkisi by summoning ancestral spirits to the container.[12] These activating substances included clays from the land of the dead (graves of prominent individuals or sacred sites), items chosen because their names sounded similar to that of the action to be performed, and metaphorical materials. In the case of the nkondi nkisi, the figure was pierced with nails, blades, screws, or other metal objects to spur the spirit into action and/or to represent different covenants and resolutions.

Although there is no evidence that Edgefield slaves made nkondi minkisi or any related wooden forms, their production of “conjure bags,” which performed similar ritualistic functions, is well documented. This lends credence to Thompson’s assertion that early Edgefield face jugs were related to the more sculptural Kongo minkisi. However, it is likely that face jugs served a variety of ritualistic functions, since the African-American community in Edgefield included people from many other areas of the Continent.

As Thompson has observed, the adaptation of Western ceramic art had precedent in the Kongo. During the last quarter of the eighteenth century, British Toby jugs (fig. 11) were sent to the Kingdom of Kongo, where they were used as a surrogate for the human skulls commonly used by Kongo lords to drink palm wine during rituals that reified their terrifying might and powers over life and death in the eyes of other community members. As such, the Bakongo transformed the relatively inexpensive Toby into a prestige object with a ritualized role. By the mid-nineteenth century, the Bakongo apparently started making their own Toby-like figures out of wood and terracotta (fig. 12). Ultimately, Thompson put forth the notion that Edgefield pots are not direct descendants of the British Toby jugs; at best, they are distant cousins that share certain visual features and have links to African ritualistic objects.[13]

Following in Thompson’s interpretative footsteps is the scholarship of historian John Michael Vlach, who explored both West and Central African influences on face jugs. He also built on Barber’s interview with Colonel Thomas Davies, noting that face jugs were initially made by slaves and then later by free African-Americans. Vlach may have overreached when he posited that face vessels were made at all of the Edgefield District potteries owing to the exchange or movement of slave workmen, but it is logical to assume that this occurred to some degree. He also noted that these enigmatic forms were found as late as 1940 in African-American households in Aiken County, where they still were regarded as objects imbued with power. Ultimately, Vlach agreed with Thompson that early Edgefield face vessels had direct links to Bakongo culture. The former also cited a historical event that would explain how West and Central African cultural traditions came to South Carolina:

One of the last slave cargoes brought into the United States was [aboard] . . . the Wanderer [which landed] in 1858 on Jekyll Island, Georgia. Most of that group were Kikongo-speaking, and they ended up near Edgefield. They were to be the last contribution of African heritage to the area, and their presence most likely provided a stimulus for sustained appreciation of face vessels by local Blacks.[14]

This event is critical to understanding early Edgefield face jugs, their relation to African ritualistic objects like Bakongo minkisi, and the significant role played by slaves who arrived on the Wanderer in 1858.

As Vlach noted, Edgefield slaves and, later, free African-Americans lived and worked in a community defined by the manufacture of pottery. Therefore their appropriation of alkaline-glazed-stoneware technology and forms for the production of ritualistic objects is logical. Thompson provided evidence of other African cultures whose materials changed, or evolved, over time. The oldest medium for representing the Yoruba god Eshu is thought to be lateritic red clay cone-shaped sculptures, used as early as 1659. The figure of Eshu was later carved out of wood, and in the twentieth century Yoruba descendants in the Americas began creating likenesses of Eshu out of concrete.[15] As Vlach suggested, those objects must be understood as creolized forms incorporating non-African pottery-making technology with African stylistic and ritualistic designs, and, in the use of kaolin, materials. Again, this can be traced to the dynamic interactions between African-American slave potters in Edgefield and the newly arrived Bakongo slaves from the Wanderer.

In 1985 art historian Regenia Perry posited that Edgefield face vessels must be seen as symbolically rich objects, laden with vital cultural implications about the makers’ backgrounds and daily life. In forwarding this theory, Perry also drew an art historical distinction between African-American–made and Anglo- or Eurocentric face vessels. In Spirits or Satire: African-American Face Vessels of the 19th Century, she proposed that early Edgefield face vessels fulfilled roles as potent, ritualistic objects, which differentiates them from the emulative and nonritualistic face vessels made later by white potters: “While the slave-made vessels appear to pulsate with an inner life, those made by Lanier Meaders and other Anglo-American imitators are very caricature-like and superficial in spirit” (figs. 13, 14).[16] “Considering the traditional African belief in spirits and souls,” Perry wrote, “it is entirely possible that African-American face vessels were commissioned and owned by individual slaves and served as their only tangible connection with the spirit world.”[17] She also noted that a number of Edgefield face vessels have histories of being recovered along the route of the Underground Railroad.[18] Building on Thompson’s ideas about the cultural centrality of spiritual practice and ritualized objects, Perry suggested that this history of migration further supports the idea that the Edgefield face vessels were connected to the spirit and ancestral worlds, as slaves would not have taken whimsical or satirical portraits with them when fleeing the plantation or, after freedom, moving north in search of work.[19]

In Great and Noble Jar: Traditional Stoneware of South Carolina, Cinda Baldwin concurred with previous scholars regarding visual similarities between the Edgefield face vessels and African sculpture and the importance of slave labor in local potteries. She also agreed with Vlach’s assertion that slaves from the Wanderer had an impact on the face-vessel tradition and added that one of the Bakongo aboard that ship, a man named Romeo, was brought to Edgefield and worked at the Palmetto Fire Brick Works.[20] As did Thompson and Vlach, Baldwin discussed the possibility that the Edgefield face vessels were indirectly connected to the Anglo-American Toby-jug tradition. Vlach specifically suggested that potters from Bennington, Vermont, who came to Kaolin, South Carolina, in 1858, might have brought the Toby tradition to that area.[21] Copies of the British Toby form were common in New England, and a pottery built by transplanted Bennington potter Anson Peeler was located near the Palmetto Fire Brick Works. Vlach’s theory was based on the aesthetic similarity between the spouts of the Toby jug’s tricorn hat and two known Edgefield face pitchers (fig. 15). However, at this time there is no evidence that the Bennington potters brought Toby jugs with them on their journey south or that the Edgefield slaves ever saw any Toby forms.[22]

One instance of a northern pottery tradition influencing Edgefield production is a stoneware harvest jug made at Thomas Chandler’s manufactory around 1850 and first published in Jill Beute Koverman’s exhibition catalog Making Faces (fig. 16).[23] Although this large-scale harvest jug is figural and predates the face vessels that are the subject of this article, its design emanates from a northern ceramic tradition. The eyes are not made of kaolin and the face is less stylized, making it difficult to discern whether the subject is representational or comical in the manner of a circus figure. Moreover, the strap-handled form and facial features are reminiscent of face vessels attributed to the Remmey family of potters from Philadelphia, which is not surprising given that Chandler trained in Baltimore in the 1820s and may have worked alongside Henry Remmey Sr. (fig. 17).[24] In overall form and date of production, and likely in function as well, Chandler’s 1840s harvest jug differs significantly from the African-American Edgefield face-vessel tradition. It is aligned not with any African customs, but rather with an earlier northeastern pottery design that in turn was directly borrowed from British customs. As such, the influence of the Chandler jug on the subsequent African-American examples should be considered cautiously. If a larger body of Chandler-made versions ever is found then it might well be logical to suggest that the face jug may have been something of a local form and played a role in the general design of the later African-American examples. For now, however, the Chandler jug is both stylistically and ritualistically different.

The most recent scholarship on Edgefield face jugs is Mark M. Newell and Peter Lenzo’s “Making Faces: Archeological Evidence of African-American Face Jug Production,” which introduced the first archaeological evidence for the manufacture of that genre of work in the Edgefield District. In addition to publishing fragments recovered from the Joseph G. Baynham site in Eureka, South Carolina, the authors surveyed previous theories pertaining to face-jug production and suggested that early Edgefield examples were tied to African practices including root magic. They also illustrated and discussed a small, circa-1900 face vessel made by South Carolina potter Mark Baynham, whom they credited with starting the “tradition of white Southern potters copying the African-style jug.”[25]

All of the aforementioned scholars agreed that slaves and, later, free African-Americans made early Edgefield face vessels, and most asserted that those objects have aesthetic and ritualistic connections to African culture. John Burrison, though, presents the problematic contention that Edgefield face jugs are part of an Anglo-American tradition. This is initially refuted by Colonel Thomas Davies’s firsthand account of slave potters working at the Palmetto Fire Brick Works as well as more recent research that has identified specific African-American potters. In “Afro-American Pottery in the South,” Burrison minimized the contributions of African-American artisans, stating that “the majority of known Black American folk potters were concentrated in Edgefield District, South Carolina, but even so they do not appear to have numbered many more than a handful, and information on them is scanty.”[26] From this questionable observation he deduced that white artisans likely made some of the pieces attributed to black potters.

Assuming, of course, that this ware was in fact made by Blacks; the documentation seems to be limited to interviews conducted by the Charleston Museum in this century, and my own research has taught me to accept oral history data only with caution. I am not seriously doubting this documentation; however, I intend to establish that there was a fairly early tradition of Anglo-American stylized face vessels, and it does not seem impossible that white potters operating in Edgefield District would have been responsible for some of the pieces attributed to Blacks.[27]

Burrison incorrectly claims that only a handful of African-Americans worked in the potteries. As with so many other industries around the time of the Civil War, when white males went off to battle, the Edgefield potteries relied heavily on slave labor, and African-Americans were in all of the potteries performing duties ranging from gathering the clay to turning vessels.[28] As Cinda Baldwin observed:

Slaves constituted a significant portion of the labor force in nineteenth-century Edgefield industry. From 1800 to 1820 the number of slaves increased four times while the white population decreased. . . . During the same period the local pottery industry, which employed a significant amount of slave labor, was established to satisfy the needs of plantations for food storage and preservation.[29]

Burrison’s thesis, which by his own admission lacked a firm evidentiary basis, ignores the face vessels’ visual similarities to African sculptural traditions and does not consider possible uses within the African-American community.[30]

The Wanderer Connection

By the nineteenth century, the slave population in South Carolina was fairly diverse, although a high proportion hailed or descended from Africans of the Congo-Angola region. Daniel C. Littlefield writes, “The cosmopolitan nature of colonial South Carolina is painted in the advertisements for slave runaways.” He goes on to describe advertisements for slaves from Angola, Bambara, Guinea, Limba, and Timmene.[31] The Africans from these different cultures brought their own traditions and rituals to the United States, many of which survived and evolved. Given the prevalence of figural terracottas in African ritualistic practices (figs. 18, 19), it is likely that more than one culture contributed to the development of Edgefield’s face-vessel tradition. Indeed, objects in that tradition are best understood as creolized forms whose use varied depending on the cultural background of the maker and/or owner.

Face vessels may have been made in the Edgefield District before 1850, but the arrival in 1858 of the slave ship Wanderer off the coast of Jekyll Island, Georgia, was a significant event in the development of that regional tradition. Although the 407 Africans aboard were illegal cargo, a group of Southern planters, led by Charles Lamar of Savannah, Georgia, conspired to acquire the slaves. He and his cohorts hoped their actions would lead to a reopening of the slave trade and secession from the Union.[32] Many of the Wanderer slaves were put on barges and trains going to Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, and Texas. About half were sent aboard the steamboat Augusta, which sailed up the Savannah River to a plantation owned by Charles Lamar’s cousin Thomas Lamar. From there, many were sent to work in northern Georgia and South Carolina, including in the Edgefield area.

In 1908 anthropologist Charles Montgomery interviewed seven of the Wanderer Africans living in the Edgefield County, Aiken County, and Augusta area: Tucker Henderson, Tom Johnson, Lucy Lanham, Ward Lee, Katie Noble, Romeo Thomas, and Uster Williams.[33] Based on Montgomery’s writings, Kikongo language scholars John Thornton and Linda Heywood assert that Tom Johnson, Lucy Lanham, Katie Noble, and Romeo Thomas came from the same area of Madimba in the valley of the Mbidizi River in the Kingdom of Kongo (fig. 20).[34] This establishes a direct connection between the Wanderer Africans and Kongo cultural traditions. Romeo Thomas appears to be a central figure in the Wanderer story as well as the face-vessel story. Originally named Tahro, he was twenty-seven when he arrived and the eldest of the Wanderer group sent to Edgefield. At the time of his death, he claimed to have been a leader in the Kingdom of Kongo, calling himself “Tahro, King of Kuluwaka, Africa.”[35]

The arrival of the Wanderer received national attention. On November 21, 1859, the New York Herald reported that a beautiful silver goblet “offered by Col. Hunt, for a specimen of native Africans to be exhibited at the State-Agricultural Fair, was taken yesterday by Dr. Bland of Edgefield. . . .”[36] Although whites appear to have been interested in the Wanderer slaves as “wild Africans” and curiosities, it is unclear how members of Edgefield’s slave community perceived them. Historian Joseph Holloway suggests that area blacks may have seen the newly arrived Africans as living conduits to their own cultural traditions.[37]

Romeo Thomas was hired at the Palmetto Fire Brick Works on at least three separate occasions.[38] Another member of the Wanderer group was Ward Lee (fig. 21), who it appears was connected with the Edgefield potteries as well. Oral tradition maintains that he was a potter, and a small white face jug that descended in his family relates very closely to sherds recovered at the Baynham site (fig. 22).[39] Reputedly made by Lee, this jug establishes a direct connection between Edgefield face vessels and a slave from the Wanderer. The object is covered in a kaolin wash that appears to have been applied after firing. As Thompson and others have noted, white substances and materials like kaolin had profound meaning in Kongo culture, and African culture in general. Evidence of the latter can be observed in the African-American practice of decorating graves with white objects such as china, clocks, and porcelain chickens.[40]

In the most general terms, anthropological and historical studies suggest that cultural traditions rarely survive unaltered when carried from one place to another. Those of the incoming group, in this case African slaves who were forcibly moved across the Atlantic, tended to merge with traditions already present in the new environment and to create new, syncretic customs. Although based on West and Central African traditions, the rituals and customs of the Wanderer slaves were adapted and modified by countless new influences and forces—the staggering restrictions of slavery, the strongly Eurocentric cultural conventions in South Carolina, the myriad traditions of African-Americans within Edgefield’s slave communities, and the simple fact that the Wanderer slaves were brought to a region that was largely defined by the production of utilitarian stoneware. This creolization of ideas and traditions is central to understanding Edgefield face vessels, which themselves are based in African practices adapted to a South Carolina context.

A growing body of evidence suggests numerous ways in which the early Edgefield face vessels are directly linked to African-inspired rituals and religious practices—including conjure, hoodoo, or root magic—that survived the trip across the Atlantic and were re-created in America. The jugs should be viewed as the product of a migrated African tradition and also as objects whose distinctive history has yet to be fully told. In South Carolina’s highly restrictive slave communities, deeply rooted African or African-American cultural ways, including the ritualistic use of face vessels, often had to be practiced covertly. Certain Africanisms—language, dress, teeth sharpening, scarification, and body piercing—were seen by many whites as evidence of the culturally backward traditions among slaves and were regarded as a threat to plantation authority. Likewise, African-inspired language, dress, mannerisms, music, and dance were viewed not only with disdain but also trepidation. Many forms of African-American social activity fit into a larger pattern of slave resistance that, among other things, provided the slave with a degree of control over his or her own life, and that kept alive distinctive cultural ways that otherwise would be stifled. Resistance, an essential survival strategy adopted by many African-Americans, took on many forms, ranging from literal, sometimes violent, acts of defiance against white rule to more subtle patterns of opposition. Examples of the latter include working at a deliberately slower pace, leaving tools out in the rain, purposefully hurting oneself, letting animals out of the barn, and breaking tools and equipment. When slaves cooperated with each other while performing these quiet acts of defiance, they were at times successful in lessening their burden. As historian John Boles explains, “The institution of slavery was a constant process of accommodation and mutual adjustment, with masters always having the upper hand but with slaves controlling a larger fraction of their lives than the system would logically seem to allow.”[41] The relative success of these and other behavioral strategies—and by extension the ritualistic power of the Edgefield face vessels—was due, in no small part, to the belief of many plantation owners and others that slaves were incapable of such well-considered tactics.[42] However, strategies of resistance were not simply about breaking the bonds of white oppression. They also kept alive modes of cultural activity, secret communication, and spiritual belief that otherwise would not have survived.

The arts of conjure, root magic, charms, spells, and other practices that were so central to life in Edgefield and other communities during the period of slavery and beyond reflect the direct continuation of time-honored African customs. Western cultural and religious practices had an impact on certain Kongo customs long before the Wanderer slaves arrived in America. With regard to Christianization efforts among the Kongo people in the sixteenth century, John Thornton notes, “Christianity was accepted, not as a new religion, but as a syncretic cult, fully in keeping with other cults in the Kongo and deriving from Kongo and not from European or Christian cosmology.”[43] If Christian precepts were present in the religious and ritualistic practices of the Wanderer slaves, they might have been imperceptible to the white population. Indeed, whites likely considered African rituals to be threatening and potentially destabilizing.[44] Scholars of African-American history have documented many distinctive social and artistic customs that had to be practiced covertly because they did not reinforce the status quo or provided too much cultural freedom to slaves. New slaves were prohibited from speaking their native language when being “broken in,” and many forms of African expression were suppressed or eliminated:

There was even a fleeting existence of African architecture, on St. Simons Island, when an African-born man named Okra suddenly built a habitation in the manner of his ancestors. The building is said to have measured approximately twelve by fourteen feet in plan, had a dirt floor, daub-and-wattle walls (“the side like basket weave with clay plaster on it”), and a flat brush and palmetto roof. In perfect evocation of the windowlessness of much sub-Saharan traditional architecture, the only source of light was the single door. But “Massa made him pull it down. He say he ain’t want no African hut on he place.”[45]

In general, many African customs were not practiced openly until the end of the Civil War. After being emancipated, former Bakongo slave Tahro (Romeo Thomas), built a small, windowless house in the style of a Kongo home or idol house (figs. 23, 24). Vlach argued that African-style dwellings served as the model for later American “shotgun” houses—the narrow, linear houses found throughout the South. Romeo’s house may have been similar to those built after the Civil War by Wanderer Africans Umwalla and Cato in nearby Hamburg, South Carolina. In an article in the Augusta Chronicle in 1888, Umwalla stated that he was born in Guinea, in West Africa, and that he regularly visited other Wanderer Africans on nearby plantations, where he enjoyed watching performances of African-American dance because they reminded him of a type of African dance.[46] The songs sung by the field hands were also familiar. When several voices joined in unison he was “carried across the ocean to the primitive scenes of his youth.” Thirty years after his forced relocation to America, Umwalla said that he was not homesick because so many of the customs in the slave quarters were very much like those of his people in Africa.[47]

The covert retention of African traditions and the widespread strategy of resistance to preserve essential cultural ways and modes of communication are seen in other ways as well. In a recent interview, ninety-six-year-old Georgia Scott, an African-American teacher born in 1916, well past the abolishment of slavery, recounted the continued use of drums for sending messages from one community to another in Aiken and Edgefield counties: “I remember as a young girl, the sound of the drum travelling across the Savannah River, telling us that someone had died or that there was to be a special meeting of a dance.”[48] This strategy was especially vital in antebellum South Carolina, where reading and writing was forbidden to slaves and general communication between slave communities was achieved by coded means such as drumming. The Wanderer Africans also used drums to communicate. Tonie Houston, a preacher from Tatemville, commented on their use of this instrument in 1940: “For their meetings, he said, Golla Tom or another would beat the drum—signaling them to gather; then all would sing and dance in a circle to the accompaniment of the drum. The drums of death would also sound, summoning the ‘setting-up or wake.’”[49]

The practice of “coding,” through the use of deception and double meanings in southern African-American communities, extended well beyond the use of drums. Secret messages or rituals were carefully inserted into seemingly innocuous African-American cultural practices, which kept slave owners from objecting and prohibiting them. In his Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, for example, Douglass described slaves singing hymns while walking through the woods on their way to a neighboring plantation: “This they would sing, as a chorus, to words which to many would seem unmeaning jargon, but which, nevertheless, were full of meaning to themselves.”[50] Spirituals were also used as vehicles to convey secret messages. For example, since African-Americans were not allowed to hold religious meetings without the presence of a white man, many met in secret. They conveyed the meeting time and place through the spirituals. Former slave Wash Wilson recalled: “When the niggers go round singin’ ‘Steal Away to Jesus,’ dat mean dere gwine be a ‘ligious meetin’ dat night. De masters . . . didn’t like dem ‘ligious meetin’s, so us natcherly slips off at night, down in de bottoms or somewhere. Sometimes us sing and pray all night.”[51] These songs were also used to warn slaves of the presence of patrollers or other dangers encountered in their daily lives, and operated as a critical response to slavery. Former slave and activist Booker T. Washington commented:

As the day [of emancipation] grew nearer, there was more singing in the slave quarters than usual. It was bolder, had more ring, and lasted later into the night. Most of the verses of the plantation songs had some reference to freedom. True, they had sung those same verses before, but they had been careful to explain that the “freedom” in these songs referred to the next world, and had no connection with the life in this world. Now they gradually threw off the mask; and were not afraid to let it be known that the “freedom” in their songs meant freedom of the body in this world.[52]

Multiple levels of meaning went undetected in part because many slaveholders and overseers believed that the singing connoted contentment, and they assumed that the songs were simple forms of entertainment. A former slaveholder, recalling a slave song about a fox, stated that it was “typical in that it shows the Negro’s fondness for dramatic dialogue and his interest in animals.”[53] In fact, this slaveholder completely misconstrued the song’s significance, unaware that in African-American folklore the fox often represents an oppressor who is outsmarted by the rabbit trickster. By the same token, white southerners did not fully understand the true meanings and uses of the face vessels.

African-American folk tales reveal a similarly strategic utilization of double hidden meanings. In the African-American folk tradition, animals were used as fictional surrogates for real-life plantation figures. The rabbit is an especially popular character in these works, and is distinguished by cleverly triumphing over stronger characters. For example, in Joel Chandler Harris’s Brer Rabbit’s Riding Horse, the character of Brer Rabbit pretends he is so sick that Brer Fox must put on a saddle in order to carry him over to Miz Meadow’s house. In this way Brer Rabbit flips the master/slave relationship while also humiliating the dominant character.[54] The slaves identified with the Brer Rabbit character, and through these stories were able to imagine a world in which they prevailed over their masters. As Lawrence Levine explains in his book Black Culture and Black Consciousness: Afro-American Folk Thought from Slavery to Freedom, “The trickster’s exploits, which overturned the neat hierarchy of the world in which he was forced to live, became their exploits; the justice he achieved, their justice; the strategies he employed, their strategies. From his adventures they obtained relief; from his triumphs they learned hope.”[55] What slaveholders perceived as whimsical tales were in actuality searing critiques of plantation life; and what were perceived as whimsical objects were highly ritualistic objects.

The African-influenced potters of Edgefield did much the same thing in taking the basic utilitarian jug form and converting it into a carefully coded spiritual object with hidden meanings. “We can be certain that these vessels were not frivolous or whimsical items,” wrote Vlach, “they are sculptures willfully created to convey a message, one known at least among a community of slave artisans and probably by the surrounding slave community.”[56] In other words, the Edgefield face vessels need to be understood as bicultural or syncretic objects that were influenced by both African and distinctly African-American cultural traditions.[57] An example of the syncretic nature of the face vessel is their possible function as water containers. The Bakongo land of the dead is believed to reside under lake bottoms and riverbeds, connecting the spirits to water. African-American history specialist Jason Young has stressed the importance of water for both the Bakongo and the enslaved African-Americans in South Carolina. As an example, he pointed to the ritual of complete water immersion in African-American baptisms, which was viewed as symbolizing a death of the old self and a birth of the new, more pure self.[58] Young argued that this ritual grew out of West African initiation rituals of complete water immersion and the Bakongo beliefs in simbi spirits. Vlach likewise drew the connection between water and the land of the dead in African-American burial practices; slave graveyards contained white seashells, as well as broken pottery and glassware, a phenomenon also found in Bakongo burial sites. He explained that “Afro-American graves may thus be read as a kind of cosmogram: the world of the living above; the dividing line of shells [or broken pottery]; the realm of the spirits, which is not only under ground but also under water.”[59]

Mirrors or other reflective objects placed on graves served as a way to speak to those who had passed away, which grew out of a pre-nineteenth-century Bakongo practice in which they communicated with the dead by looking into a pool of water. Based on these beliefs about the power of water, it is significant that the Edgefield face jugs are in fact hollow vessels, and not flat dishes or solid sculpture. They are all containers that could have held water, and, according to oral history, have been found in African-American graveyards.[60]

The vessel form was likely a purposeful choice based on the known conduits to the spirit world, whose true meaning was kept hidden from the white community. Edwin Atlee Barber wrote that in 1862 Colonel Thomas Davies witnessed his slaves making face jugs, which he described as “weird-looking water jugs.”[61] The key point is that face jugs fall into the tradition of coding and what was simply a “water jug” to Davies might have been something very different to people within the African-American community. Davies’s comment shows that their making was not hidden from the view of the white pottery owners. The African-Americans may very well have encouraged the misinterpretation of the form as simply an odd drinking vessel, leaving the owners unaware of its hidden meanings and uses. Vlach alludes to this deliberate deception:

In the presence of the ferocity and energy expressed by the best of these Afro-Carolinian vessels, one senses a shift in the attitude, a craft based on the self-generated incentive of a vital culture, standing apart from the nature of most pre-Civil War Southern Afro-American industry. The distinction, the writer would guess, stems from the fact that the Afro-American craftsmen made these vessels for themselves and their people for traditional reasons of their own. Under the noses of their masters they succeeded in carving out a world of aesthetic autonomy.[62]

The complexity of African-American religious and ritualistic practices cannot be overstated, and the covert or concealed nature of many of the traditions makes their interpretation today all the more difficult. In Come Shouting to Zion: African American Protestantism in the American South and British Caribbean to 1830, authors Sylvia Frey and Betty Wood argue that “the passage from traditional religions to Christianity was arguably the single most significant event in African American history. . . . It provided Afro-Atlantic peoples with an ideology of resistance and the means to absorb the cultural norms that turned Africans into African Americans.”[63] This is not to say that traditional African religious beliefs were abandoned. Rather, African-Americans often customized Christian practices to cope with the harsh realities of enslavement. Some aspects of African religions were adapted to Christianity, whereas others were practiced in addition to Christianity, such as conjure and root work. Slave-religion expert Albert J. Raboteau expounded that “adaptability, based upon respect for spiritual power wherever it originated, accounted for the openness of African religions to syncretism with other religious traditions and for the continuity of a distinctively African religious consciousness.”[64] The aforementioned practices—drumming, storytelling, music, and the like—reveal a process of adaptation and assimilation of African beliefs into African-American beliefs and rituals.

Visual and historical evidence strongly suggests that the early Edgefield face vessels were directly inspired by African culture, which was reintroduced to this area with the landing of the Wanderer, and also by local African-American cultural traditions as practiced in slave and free black communities. To gain fuller insight into the vessels’ formal and ritualistic attributes, it is essential to explore the African beliefs from which they came. In most African societies, ritualistic pottery vessels are visually complex, just as jugs are more ornate than contemporaneous utilitarian jugs. In Four Moments of the Sun, Thompson discusses a type of terracotta vessel called a diboondo (plural maboondo) (fig. 25). The diboondo resembles a cylindrical or quadrangular hollow column divided into horizontal registers and is placed on the tombs of important Bakongo. The maboondo are perforated with triangles, squares, and diamond shapes and are incised with different designs as well as sometimes decorated with applied figures. These vessels were meant to be spiritual containers. As with so many examples of material culture, these vessels blur the line between art and culture, form and function.

Thompson’s pivotal scholarship emphasized the distinctive and symbolically charged use of kaolin, a pure-white river clay that in a West African context was widely regarded as having magical properties and can be linked to many ritualistic customs. The purposeful addition of kaolin to ceramics and other ceremonial objects in Africa—as in Edgefield, South Carolina—mimics that used to activate a connection to the spirit world. Diviners in Baule culture (Côte d’Ivoire), for example, rub kaolin over their eyes and mouths in order to initiate communication with the spirits while in a trance.[65] Carved Baule divination figures that depict humans mirror this practice by also featuring kaolin around the eyes (fig. 26). In West Africa, Vodun worshipers “who desire to enter the spirit world, similarly cover their bodies with white kaolin powder considered ‘food for the gods’. This dramatic form of body painting allows the devotee to attain the highly sought state of possession, whereby a deity may enter his body and empower him.”[66] The Fang similarly use kaolin to connect to the spirit of the dead, and the Bembe apply kaolin over their masks’ eyes to suggest the ability to see into the spiritual world. The implications of the use of kaolin on the Edgefield face vessels are even stronger in light of other African cultural traditions.

As Gary Zabel writes, for example, the Bakongo believe that the land of the dead is a mountain made of kaolin, and that white is the color of the spirit world:

In that extraordinary land of kaolin, in that invisible looking-glass realm, those who have led a basically upright life clear through to its conclusion have the opportunity to purge themselves of remaining moral impurities. They then enter the cycle of existence once again by being reincarnated in the form of their own grandchildren. Those who have conducted themselves in an especially righteous way are transformed into immortal simbi spirits who take the shape of pools, waterfalls, stones, and mountains.[67]

Rubbing kaolin on or placing it inside minkisi was a necessary way, both literally and symbolically, to establish a connection to this purified place. As with the Baule, Bakongo diviners would also rub the white kaolin around their eyes and mouths to better see and speak to the spirits.[68]

Many West African cultures place particular importance on the head as the location of identity and force of life. The Yoruba created pots that featured human faces and were used in a variety of rituals. A Songye power figure called a nkishi (similar to a nkisi; plural mankishi) is carved in the form of a male. Alisa LaGamma explains that “mankishi enhance the overall quality of life by assuring that universally shared concerns, such as procreation, protection against illness, witchcraft, and war, are addressed through divine intervention.”[69] The physical attributes of each sculptural form are first determined by a conversation between the nganga and the ancestral realm or spirit world. As LaGamma notes, “the physiognomy and regalia of a community nkishi emphasize the influential character of its subject, conveying a degree of physical strength and social rank commensurate with the spiritual powers it commands.”[70] Typically, the heads of these figures are disproportionately large in relation to the body, and also feature wide, almond-shaped eyes, an unusually broad forehead, and a jutting beard. But again, these attributes are emphasized for a reason. To the Songye people, the broad forehead symbolizes omnipresence, the beard symbolizes leadership, and the large eyes symbolize contemplation, all to convey the notion that the spirit occupies the figure.[71]

The kaolin-decorated Edgefield face-vessel forms are heads, rather than full bodies in the manner of carved wooden nkisi figures (fig. 27), which is fully consistent with keeping intact an African tradition of honoring the head as the force of life and container of spiritual powers. As with most African sculptural forms related to the human body, the Edgefield face vessels are not meant to be individualized portraits or caricatures. Rather, they function in a totemic way and their features have symbolic meaning. The large kaolin eyes and teeth connote the ability to see and talk to the spirits (fig. 28); the beards, present on some face vessels, denote wisdom.

The Art of Conjure and Edgefield Face Vessels

Among the many African cultural rituals that persisted during and after slavery was the practice of conjure—also root magic or root medicine—a widespread African-influenced system of magic still practiced in the South.[72] Born out of West and Central African divination and spiritual practices, conjure was prevalent in North American slave communities in the nineteenth century. In fact, the 1900 census for the Schultz Township of Aiken, South Carolina, lists Richard Phillip as working in root medicines (fig. 29).[73] Aiken was known as a center of conjure in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[74] Conjure was used for diverse purposes, from protection and healing to causing harm to others. It was perceived as providing an additional level of protection for its practitioners. Raboteau explained the function of conjure in this way:

Primarily, conjure was a method of control: first, the control which comes from knowledge—being able to explain crucial phenomena, such as illness, misfortune and evil; second, the control which comes from the capacity to act effectively—it was “a force . . . by which man can (or thinks he can) achieve almost every desired end” . . . third, a means of control over the future through reading the “signs”; fourth, an aid to social control because it supplied a system whereby conflict, otherwise stifled, could be aired.[75]

The actual practice of conjure, which in Edgefield might have included the use of face vessels, helped slaves cope with the realities of plantation life by providing them with a degree of power. It not only functioned outside white authority but also could be activated by slaves against their owners. A former slave from South Carolina interviewed for the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration stated: “Conjin ‘Doc.’ say dat he done put a spell on ole Marse so dat he wuz ‘blevin ev’y think dat us tole him bout Sa’day night and Sunday morning.”[76] Slaves seem to have turned to conjurers for help with everything from love spells to revenge against another slave to protecting themselves against the violence that white Christian preachers were telling them was justified.

Conjurers, or conjure doctors, tended to be elderly slaves or newly arrived Africans.[77] They were considered to be wiser and more closely tied to the supernatural world, and emphasized the use of charms and counter-charms to protect or harm. Conjurers created charms by combining certain magical materials inside a container. The most common materials included in these conjure bags were hair, nail clippings, personal objects belonging to the victim, grave dirt, roots, and powders. There can be little doubt that this practice was well established long before Bakongo slaves arrived on the Wanderer. Many of the Wanderer slaves, including Romeo Thomas and Cudjo, claimed to be kings, queens, or princesses—an approximation, most likely, for African terms that denoted tribal leaders, chiefs, and ngangas.[78] In addition to the claims of prior privilege and leadership, there are many recorded instances of Wanderer Africans being treated as persons of privilege by their peers and of them practicing magical rites and root medicine, both associated with persons of special stature in African communities. Bettis C. Rainsford recounted a story wherein Sarah Bull Barnwell, widow of John Gibbs Barnwell of Beaufort, reportedly purchased two Wanderer slaves—a man and a woman—paying for them in gold. The woman had been a princess in Africa and the man subsequently became her husband.[79]

Evidence suggests that members of slave communities in the South believed that native Africans had special powers, such as the ability to hoe a field without picking up a tool, or to rise up and fly home to Africa.[80] Prince Sneed of White Bluff, Georgia, recalls his grandmother telling him of how Africans shouted, “‘Kum buba, yali kum buba tambe, dum kunka yali kum kunta tambe.’ Then they rised off the ground and fly away.”[81] As noted earlier, powerful Kongo Africans fulfilled the roles of nganga, or medicine men, in their villages. They were charged with assessing situations in which magic was believed to have inflicted harm. They would then use charms, spells, and spiritual objects such as nkisi to resolve the matter.[82]

The beliefs and practices associated with conjure were largely imported with enslaved Africans into America, the Caribbean, and South America. In addition to the use of traditional charms and spells, African slaves and their descendants incorporated other objects into their belief systems—such as the use of a silver coin around the ankle to ward off evil or give warning of a malefic conjure (fig. 30). Slaves also turned to root magic, as the medicinal counterpart to conjure. It was consistently practiced in South Carolina—sometimes in addition to traditional Western medicine, sometimes instead of it. Africans imported by the Wanderer into the southeastern United States, especially in the Edgefield area, were adept in the practice and application of root magic.[83]

The Edgefield and Aiken areas are reported to have been at the center of conjuring activity.[84] A specific example of conjure from 1868 was published in the Herald, which related a story of Randall and Lizzie Williams on the Woods Plantation near Aiken. Lizzie had fallen ill and, after receiving no benefit from the attendance of several physicians, was led to believe she had been “conjured.” As a last resort, Randall contacted a “Voodoo Doctor,” who sent them to another alleged “sorcerer in Edgefield County.” The sorcerer said that a diligent search of the property would reveal the cause of his wife’s troubles. The “charm” was subsequently found and said to have been “hand made, and when found the next day was the wonder of all the African Americans in the neighborhood.”[85] Next, by direction of the Edgefield sorcerer, Williams took the charm to the river (water being where spirits lived) and, walking backward, approached the water and tossed the charm over his head into the current. It was reported that from the day the charm was found, Lizzie Williams began to improve “and is now as active and sprightly as any young girl on the plantation.”[86]

Twenty years later a group of African-Americans gathered in Augusta, Georgia, to observe a conjure. By the doorstep of a house were two objects made of red flannel containing a rabbit foot, some dried herbs, and a substance a woman said was a powdered frog. At the corner of the house was another charm—a tomato can stuffed with roots, red flannel, and two or three pieces of hide with hair attached—which this woman believed had been used by her landlord to terrorize his tenants into paying on time. It was reported that the cure for the charm was that it “must be buried on the first moonlit night at 12 o’clock to destroy its power.”[87] These narratives and more prove that conjure was prevalent within the African-American community in South Carolina.[88]

In conjure, charms are often buried under the doorstep, to be activated by the person as he or she steps through the doorway or onto the front step. As Jeffrey Anderson explained in Conjure in African American Society, “all that an enemy has to do is get some of his victim’s hair, his nails or water in which he has bathed and have a witch doctor make a concoction which buried in front of the victim’s door or secretly hung in his room will bring sure death.”[89] In addition, the doorway was believed to be the spot one would place a broom to keep a witch from entering the house.[90] This has a West African precedent. Newbell Niles Puckett has explained that the Susu-speaking people believe “witches are born, not initiated, they put inside a man’s house ‘medicine’ in a pot, consisting of rice, groundnut sesame and fundi, which is buried inside the door and causes him to get a bad crop.”[91]

Oral tradition around Edgefield and in other areas reveals that face jugs were purposefully placed in the doorways of African-American homes. For example, Ward Lee’s great-granddaughter, Mrs. Pat Bishop, related that in addition to the jug illustrated in figure 22, a blue-and-white face vessel was placed at the door of her father’s house.[92] In 1956 Mrs. Frances Harris, another Edgefield resident who was related to a Wanderer slave, recalled a face vessel that her mother-in-law kept by the door. It was, she said, “kept all shined up and looking pretty by the door.”[93] The Reverend Alexander Pope, also of Edgefield County, remembered seeing face jugs used as doorstops.[94] These instances suggest a ritualistic function of the face jug in proximity to the spiritual portals of doorways.[95]

When asked specifically about the historical use of face vessels in the community, Edgefield historian Wayne O’Bryant stated, “We have always known what face vessels were used for, they were conjure jugs. No one has ever asked us before.”[96] The face jug illustrated in figure 31 might be a “conjure jug.” Coated with a brownish olive-green glaze, the jug features a unibrow and ears with a defined tragus, kaolin eyes and teeth that are glazed (those areas were waxed on most Edgefield face vessels to prevent the glaze from adhering), black pupils, and a rare two-word inscription on the back (fig. 32). The first word is “Squire,” which, with “Esquire,” was a common first name in South Carolina during the nineteenth century. The second word is less legible, although some observers have interpreted it to read “Pope” or “Peter.” The 1880 U.S. Census for the township records an African-American by the name of Squire Pope living alongside pottery workers in Shaws Township, Edgefield.[97] “Squire” and “Peter” were also found in the Freedman’s Savings Bank records of a former slave by the name of Glasco Middleton (b. 1835).[98] Middleton had two children named Squire and Peter.[99] However, when the inscription is examined in raking light, the second word appears to be “Pofu,” which could refer to a number of things. Pofu is the name of a town in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Swahili dictionaries define pofu as “blind” or “to make blind,” and a late-nineteenth-century Kikongo dictionary defines mpofo as “blind.”[100] In The Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts, John Michael Vlach points out that Kikongo words were in use in South Carolina in the nineteenth century.[101] Many of the Wanderer Africans also spoke Kikongo.[102] If the second word on the jug is “Pofu,” the inscription would translate “the blind Squire.”

Like the inscription, the glazed eyes on this jug may indicate that it was intended for conjures to either cause or cure blindness. Blindness was one of the most common conjures in South Carolina. Baldwin referred to the former Wanderer slave Uster Williams, who believed he had been blinded by a spell.[103] In Folk Beliefs of the Southern Negro, Newbell Niles Puckett recounted:

Another conjurer tells me that anvil-dust (he calls it “Allerkerchie”) is mixed with a person’s food or put in his hatband. That, in his food, will “rot his guts and make snakes inside of him,” while that, on his hatband, will make him go entirely blind. The reptile-dust is the common mode, however; and kept in a little vial in my conjure collection always won respect and opened wary mouths.[104]

African traditions rarely survive unaltered in the New World. Therefore, even though Edgefield face vessels were influenced by the Bakongo culture, they were not straightforward minkisi nor did they solely perform the same function. Rather, the minkisi inspired a new conjure-vessel form; one that may have been considered more powerful since it had kaolin integrated into the form.[105] Jason Young’s work supports this notion. He states that, “black American conjure traditions were not mimetic; rather, they established a ritual space where Africa was both remembered and (re)imagined. In the end slaves elaborated on the Kongo minkisi and created new ritual objects, replete with their own construction and with their own manner of invocation.”[106]

Although there is much evidence to support the argument that the early Edgefield face vessels are polyritualistic objects derived from a Kongo belief system brought over by the slaves on board the Wanderer, research on these iconic vessels continues. “Face Jugs: Art and Ritual in 19th-Century South Carolina” and “Unmasking the Mysteries of Face Jugs,” recently hosted by the Columbia Museum of Art and the McKissick Museum of Art, are examples of ongoing interest in the face jug topic. New archaeological research focusing not only on face-jug sites but also on the Wanderer slaves is being conducted by a consortium from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.[107] Material analyses of the face vessels have been initiated by the Chipstone Foundation in order to better understand their chemical composition, and cultural research continues. One thing is already clear, though—the Edgefield face vessels have sparked an incredible response from a wide variety of researchers, collectors, and enthusiasts. While the utilitarian and ritualistic functions of these vessels might never be fully understood, there is no question that face jugs were important objects in the lives of the nineteenth-century Edgefield community of enslaved and freed African-Americans.

Sallie Layton Keenan, “Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936–1938, South Carolina Narratives, Volume XIV, Part 3,” p. 78, available online at http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=mesn&fileName=141/mesn141.db&recNum=0 (accessed December 3, 2013).

Harvey S. Teal, Partners with the Sun: South Carolina Photographers, 1840–1940 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2001), p. 125. Palmer is remembered as an artist who took photographs throughout Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina, specializing “in scenes from the black community, including not only portraits, but also their cabins and ‘at work’ scenes in cotton fields and other locations.”

A similar image in the series features an African-American woman.

At the time, this iconography was popularly associated with the Aesthetic Movement. Wilde was a well-known proponent of this controversial style, which was derided by many social and style leaders for its effeminate and immoral character.

The section on Edgefield face jugs as well as the conversation with Colonel Davies are not in the two previous editions of the book.

Edwin Atlee Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States and Marks of American Potters, rev. and enl. ed. (New York: Feingold & Lewis, 1909), p. 466. Some scholars have questioned this recollection on the basis of it being recorded forty years after the fact; it remains the only firsthand written account referencing Edgefield face jugs, however, and there is no evidence it should be distrusted. In Early American Pottery and China (New York: Century Company, 1929), author John Spargo referenced Barber’s description but added that “we know practically nothing” about the “grotesque stoneware jugs” (p. 347).

Thompson suggested that “a connection between Congo-Angola arts and South Carolina pottery made by Afro-Americans is a distinct possibility and would seem likely in view of the particular slaving history of the area. This correspondence, if proved, would make definite the links between the Bakongo and Aiken County pottery.” Thompson, Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy (New York: Random House, 1983), p. 41. It is our contention that the correspondence can be proved. Bakongo is a term coined in the 1910s to describe the peoples who speak the Kikongo language. The inhabitants of the Kingdom of Kongo called themselves Essikongo.

Robert Farris Thompson and Joseph Cornet, The Four Moments of the Sun: Kongo Art in Two Worlds, exh. cat. (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1981), p. 158.

Thompson, Flash of the Spirit, p. 118. Thompson and Cornet, Four Moments of the Sun, pp. 157–62.

Monica Blackmun Visonà, Robin Poynor, and Herbert M. Cole, A History of Art in Africa, 2nd ed. (Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson/Prentice Hall, 2008), pp. 359–60.

Thompson, Flash of the Spirit, p. 117.

The authority of a nganga was precarious and was constantly challenged.

Thompson, Four Moments of the Sun, pp. 157–62.

John Michael Vlach, The Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts, exh. cat. (1978; repr. with new preface, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1990), p. 86.

Thompson, Flash of the Spirit, p. 24.

Regenia Alfreda Perry, Spirits or Satire: African-American Face Vessels of the 19th Century, exh. cat., Gibbes Art Gallery, Charleston (Charleston, S.C.: Carolina Art Association, 1985), pp. 7–8.

Ibid., p. 10.

Ibid.

An example is an Edgefield face vessel that was given as a gift about 1917 by the son of a former Southern slave to the manager of a “poor farm” in Hingham, Massachusetts. The son was destitute and the jug was his only possession; the informant stressed that the vessel held much importance for the son and that he held it in high regard: “The vessel was in perfect condition and obviously well cared for. This was never in a field or used for utilitarian use. I have worked in a field and this jug would not be enough to quench a worker’s thirst nor could it have stayed so well preserved. There is not a scratch on it.” Pat Van Der Lind, personal communication with April Hynes, April 10, 2012.

Cinda K. Baldwin, Great and Noble Jar: Traditional Stoneware of South Carolina (Columbia: McKissick Museum of the University of South Carolina; Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1993), p. 82.

Kaolin was part of the Edgefield District.

Baldwin acknowledged that the Bakongo Africans newly arrived on the Wanderer might have inspired the potters in Edgefield to create Toby-like vessels. Specifically, she references Thompson and his argument that Toby jugs were appropriated by chiefs in the Kongo to serve a magical ritualistic purpose. Baldwin, Great and Noble Jar, p. 81.

Jill Beute Koverman, Making Faces: Southern Face Vessels from 1840–1990 (Columbia: McKissick Museum of the University of South Carolina, 2001), p. 7. Koverman cites a Romanesque nose found at the Phoenix Factory site by Stephen Ferrell as evidence that Chandler may have made other face vessels.

See, in this volume, Philip Wingard, “From Baltimore to Edgefield: The Influence of Thomas Chandler on 19th-Century Stoneware,” pp. 38–76.

Mark M. Newell and Peter Lenzo, “Making Faces: Archeological Evidence of African-American Face Jug Production,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 2006), p. 126.

John A. Burrison, “Afro-American Folk Pottery in the South,” in William R. Ferris, ed., Afro-American Folk Art and Crafts (Boston: G. K. Hall, 1983), p. 336.

Ibid.

There is evidence that slaves worked in the potteries before the Civil War as well. Dave Drake, for example, produced signed pots for the Lewis Miles pottery as early as 1840. Arthur F. Goldberg and James P. Witkowski, “Beneath His Magic Touch: The Dated Vessels of the African-American Slave Potter Dave,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 2006), p. 71.

Baldwin, Great and Noble Jar, pp. 71–72. Baldwin makes multiple references to slaves working in the Edgefield potteries.

Michael D. Hall also made the argument that the Edgefield face vessels were made by white potters. He goes a step further than Burrison, speculating that face vessels were neither ritualistic nor whimsies, but rather were linked to the nationwide Temperance Movement, a theory that lacks supporting evidence. Hall, “Brother’s Keeper: Some Research on American Face Vessels and Some Conjecture on the Cultural Witness of Folk Potters in the New World,” in Stereoscopic Perspective: Reflections on American Fine and Folk Art, Contemporary American Art Critics 11 (Ann Arbor, Mich.: UMI Research Press, 1988), pp. 195–225. Burrison does not discount the possibility of the face jugs being inspired by an African tradition, although he suggests they also were inspired by European forms: “Germany and Africa, then, are two possible sources for American face jugs, with a third possibility that they arose independent of any Old World influence.” John A. Burrison, “Fluid Vessel: Journey of the Jug,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press for the Chipstone Foundation, 2006), p. 113. Following a discussion of a Nigerian portrait pot and the Thomas Chandler face jug, Burrison stated, “Did Chandler then introduce the concept to Edgefield slave potters, or were they working in a separate, perhaps African-based tradition? We now know that the face jugs of Cheever and Lanier Meaders were part of a continuous Anglo-Southern tradition, but whether ultimately inspired by slave-made examples, as Thompson suggests, might never be learned.” Ibid., p. 115.

Daniel C. Littlefield, Rice and Slaves: Ethnicity and the Slave Trade in Colonial South Carolina (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991), p. 115.

In 1808 the federal government made the importation of slaves directly from Africa illegal.

Charles J. Montgomery’s article states that Tom Johnson came from the east coast of Africa “[w]here you can see the water just drippin’ out o’ the sun.” Based on Professor John Thorntorn’s unpublished research (“Enslavement of Wanderer,” unpublished manuscript), though, it is more likely that he came from the Kingdom of Kongo. Uster Williams came from the “Bezy River” in Africa. He recalled his African customs in remarkable detail and believed a “Spell” was placed on him through “witchycraft.” Ward Lee, also known as Cilucangy, came from the village of Cowany. Tucker Henderson was eighteen years old when he arrived from Africa. Tahro, also known as Romeo, was the oldest of the group and came from Kuluwaka Africa. Montgomery, “Survivors from the Cargo of the Negro Slave Yacht Wanderer,” American Anthropologist, n.s., 10, no. 4 (1908): 613–14.

It is likely they were partisans of Pedro V, who lost a battle at São Salvador at about the same time the Wanderer arrived.

Luweka means “to arrive” in Kikongo, whereas ku is a locative particle. Kuluwaka may thus mean “the place of arrival.” These groups, called kanda in Kikongo, were often connected by kinship or common purpose. John K. Thornton, “Elite Women in the Kingdom of Kongo: Historical Perspectives on Women’s Political Power,” Journal of African History 47, no. 3 (2006): 439.

There are several newspaper articles that describe the wonder and excitement produced by the Wanderer Africans. One of the sources is the November 21, 1859, issue of the New York Herald, which states: “The premium offered by Col. Hunt, for a specimen of native Africans to be exhibited at the State-Agricultural Fair, was taken yesterday by Dr. Bland of Edgefield who brought two on the grounds. Their arrival created quite a sensation with the large crowd assembled in the amphitheater. The premium was a beautiful silver goblet.”

Joseph E. Holloway, ed., Africanisms in American Culture (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990), p. 39.

Davies Personal Papers, South Carolina Department of Archives and History, Columbia.