Charles Willson Peale, Benjamin Randolph, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1775–1780. Watercolor on ivory. 1 1/4" x 1". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; gift of Mr. and Mrs. Timothy Johnes Westbrook, 1990.)

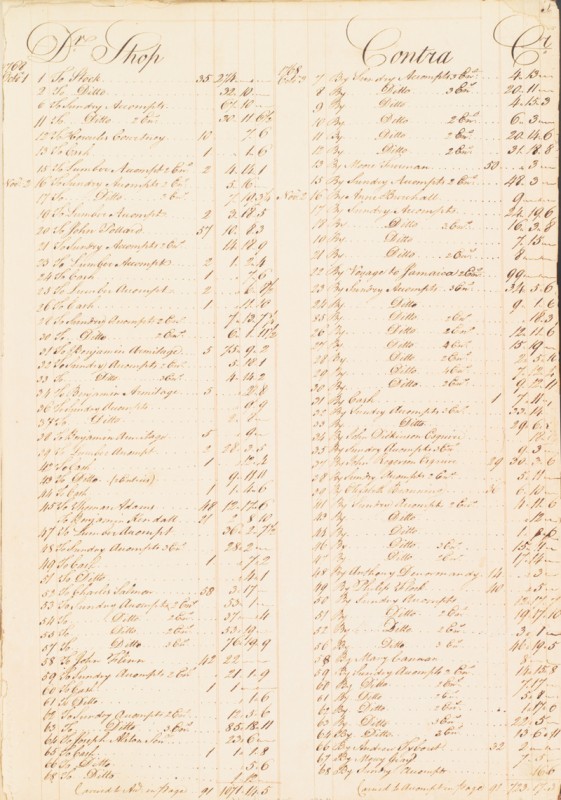

Page 3 from Benjamin Randolph’s account book. (Courtesy, Manuscripts and Archives Division, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.)

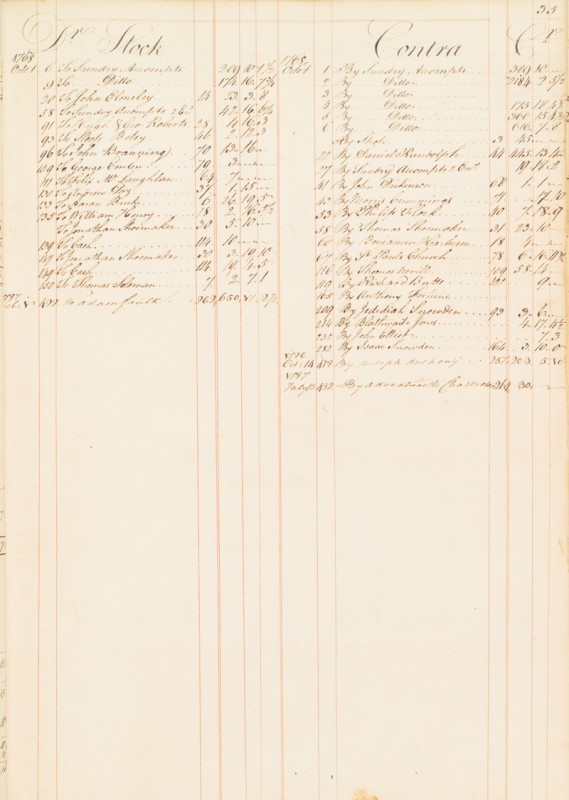

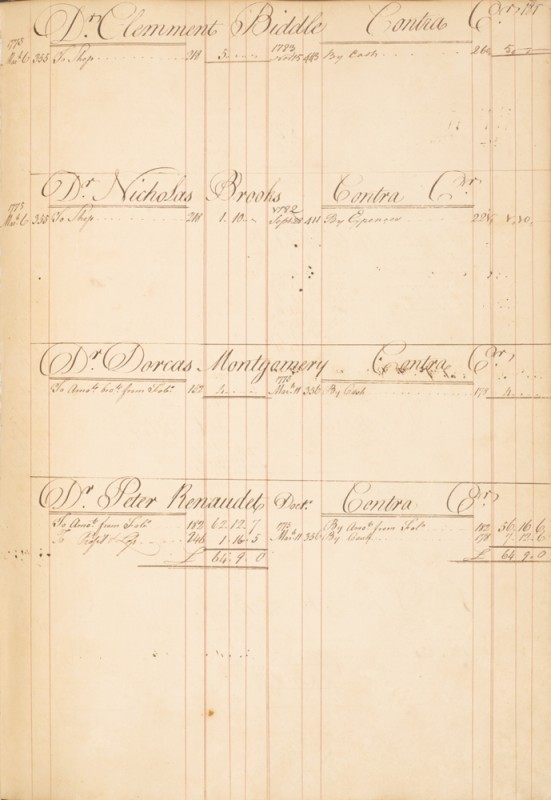

Page 35 from Benjamin Randolph’s account book. (Courtesy, Manuscripts and Archives Division, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.)

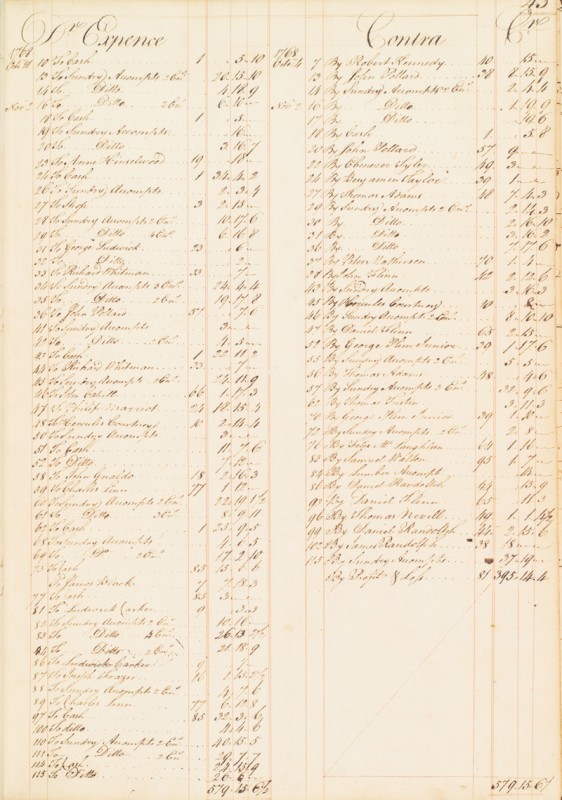

Page 43 from Benjamin Randolph’s account book. (Courtesy, Manuscripts and Archives Division, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.)

Chimneypiece from the Samuel Powel House, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the center tablet of the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 5. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth).

Chimneypiece from the Thomas Ringgold House, Chestertown, Maryland, ca. 1770. (Courtesy, Baltimore Museum of Art.)

Detail of the frieze appliqué over a door from the Thomas Ringgold House. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the frieze appliqué on the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 7. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Design for a frieze appliqué illustrated on pl. 2 in Thomas Johnson’s A New Book of Ornaments (1762). (© V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London, www.vam.ac.uk.)

Benjamin Randolph, side chair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770. Mahogany. H. 38 1/8", W. 23 3/4", D. 19". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, M. and M. Karolik Collection, © 2000, all rights reserved.)

Armchair attributed to the shop of Benjamin Randolph, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770. Mahogany. H. 37 5/8", W. 24 3/4" (seat), D. 19 3/4" (seat). (Private collection; photo, Joe Kindig Antiques.)

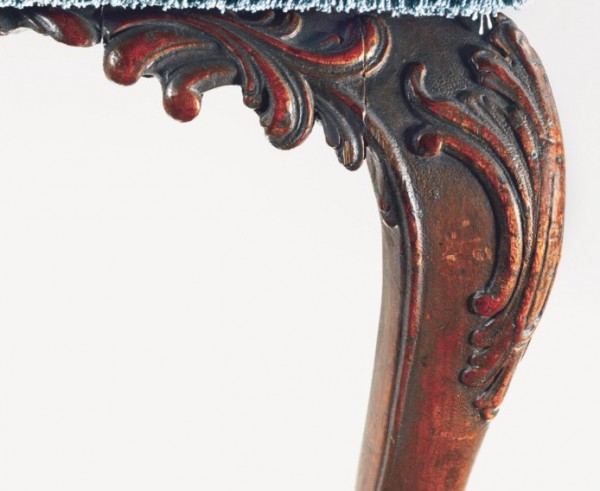

Detail of the knee carving on the side chair illustrated in fig. 11.

Detail of the knee carving on the armchair illustrated in fig. 12.

Tea table attributed to the shop of Benjamin Randolph, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1765–1775. Mahogany. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; photo, Joe Kindig Antiques.)

Detail of the knee carving on the tea table illustrated in fig. 15.

Card table with carving attributed to Hercules Courtenay, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1765–1775. Mahogany with unidentified secondary woods. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; photo, Mack Coffey.)

Detail of the knee carving on the card table illustrated in fig. 17.

Detail of the right mantle truss of the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 5. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

High chest attributed to the shop of Benjamin Randolph, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1765–1770. Mahogany with poplar, yellow pine, and cedar. H. 89 7/8", W. 46 1/8", D. 23 5/8". (Courtesy, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.)

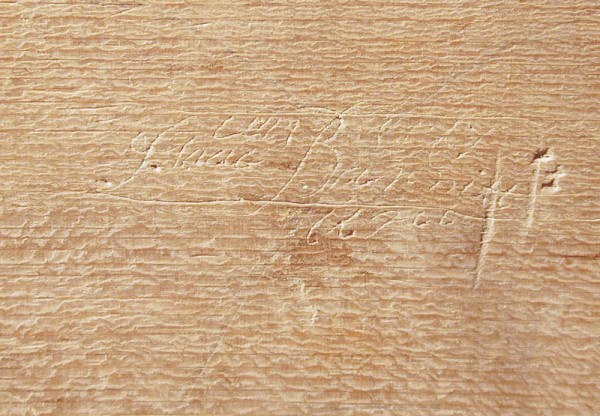

Detail of the inscription on the high chest illustrated in fig. 20.

Detail of the carving on the lower shell drawer of the high chest illustrated in fig. 20.

Detail of the knee carving on the high chest illustrated in fig. 20.

Base of a high chest with carving attributed to John Pollard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1765–1775. Mahogany with yellow pine, sweet gum, and white cedar. H. 38", W. 45 5/8", D. 22 13/16". (Courtesy, Diplomatic Reception Rooms, U.S. Department of State.)

Detail of the carving on the center drawer of the high chest base illustrated in fig. 24.

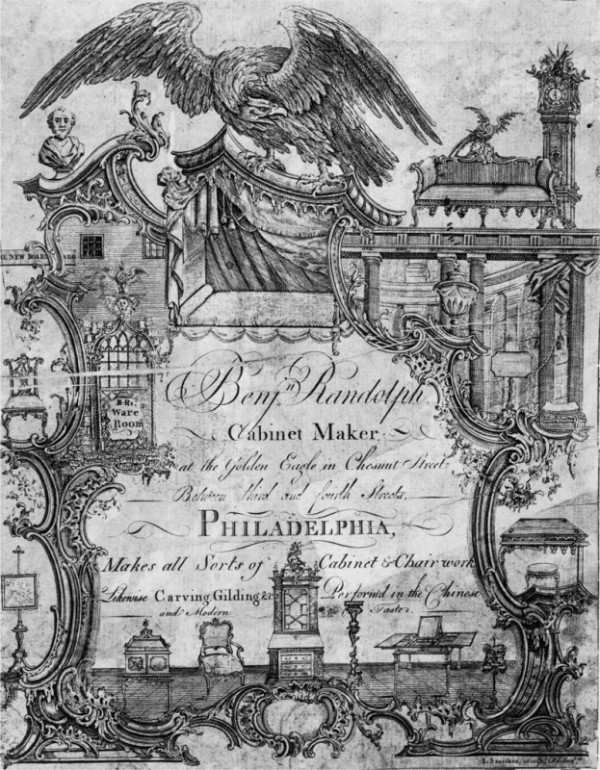

James Smither, trade card of Benjamin Randolph, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1769. Engraving on paper. 7" x 9". (Courtesy, Library Company of Philadelphia.) The desk-and-bookcase at the bottom center was copied from an engraving in Thomas Chippendale’s Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (see fig. 27). No other contemporary reproduction of that image in Philadelphia is known.

Design for a desk-and-bookcase illustrated on plate 108 in the third edition of Thomas Chippendale’s Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1762) This design appeared on pl. 78 in the first (1754) and second (1755) editions.

Desk-and-bookcase attributed to the shop of Benjamin Randolph, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Mahogany with yellow pine, white cedar, poplar, and white oak. H. 114 1/4", W. 53 3/4", D. 26 7/8". (Courtesy, Kaufman Americana Collection; photo, Dirk Bakker.) The lower case of this desk-and-bookcase was derived from a design in Thomas Chippendale’s Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (see fig. 27). The only other Philadelphia case piece with details corresponding to that design is a desk-and-bookcase (see fig. 31) with feet like those on the example shown here.

Detail of the carving on the left door adjacent to the lower drawers of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 28. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

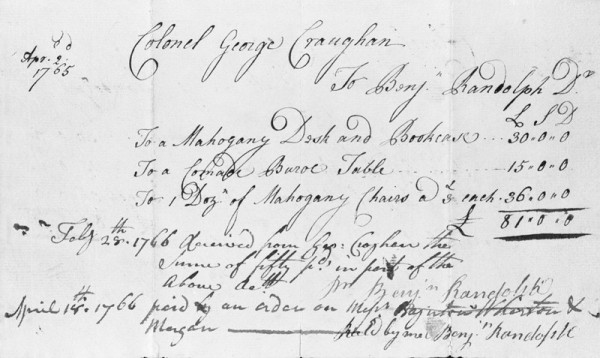

Bill from Benjamin Randolph to George Croghan. (Courtesy, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Cadwalader Collection.)

Desk-and-bookcase attributed to the shop of Benjamin Randolph with carving attributed to John Pollard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770. Mahogany with tulip poplar and white cedar. H. 98 1/2", W. 46", D. 25 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the left front foot of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 28. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the left front foot of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 31. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the carving on the prospect door and flanking drawers in the writing compartment of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 31. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Benjamin Randolph, card table, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1765–1775. Mahogany with white oak and poplar. H. 28 3/4", W. 33 1/4", D. 16". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Detail of the knee carving on the card table illustrated in fig. 35.

High chest attributed to the shop of Benjamin Randolph, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770. Mahogany with poplar, yellow pine, white oak, and white cedar. H. 90 1/4", W. 45 5/8", D. 25 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Detail of the knee carving on the high chest illustrated in fig. 37.

Detail of the tympanum appliqué of the high chest illustrated in fig. 37.

Detail of the garland to the right of the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 7. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

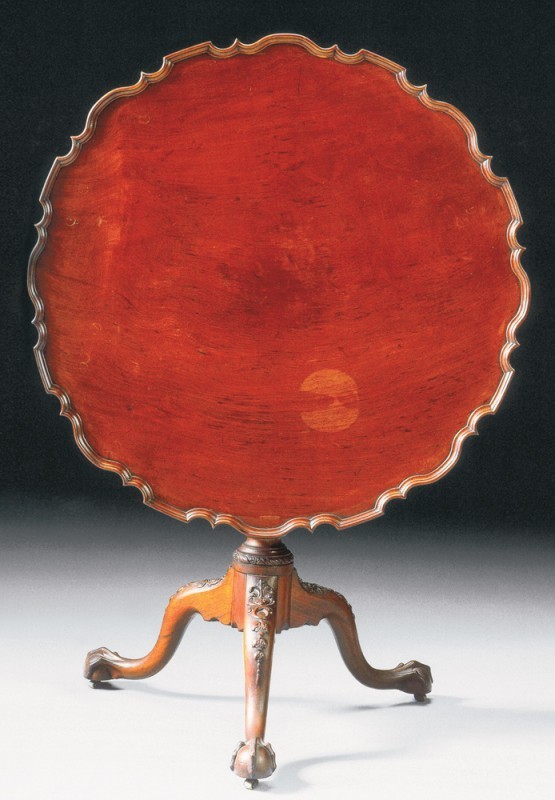

Tea table attributed to the shop of Benjamin Randolph, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1775. Mahogany. H. 29 1/2", diam. of top: 35". (Private collection; photo, Christie’s.)

Page 181 from Benjamin Randolph’s account book. (Courtesy, Manuscripts and Archives Division, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.)

Detail of the knee carving on the tea table illustrated in fig. 41.

Easy chair attributed to the shop of Benjamin Randolph with carving attributed to John Pollard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1765–1775. Mahogany with white oak. H. 45 1/4", W. 24 3/8", D. 2715/16". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, purchased with museum funds, 1929.)

Sideboard table attributed to the shop of Benjamin Randolph with carving attributed to John Pollard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1765–1770. Mahogany with yellow pine and walnut. H. 32 3/8", W. 48", D. 23 1/4". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1918 [18.110.27]; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Details showing from top to bottom the carving on a side rail of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 44; the side rail of the sideboard table illustrated in fig. 45; and the left frieze appliqué below the mantle of the chimneypiece from the Stamper-Blackwell parlor.

Design for a pier glass and table illustrated on pl. 152 in the third edition of Thomas Chippendale’s Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1762). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Side chair, attributed to the shop of Benjamin Randolph, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1769. Mahogany with white cedar. H. 36 3/4", W. 21 3/4" (seat), D. 17 7/8" (seat). (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Charles Willson Peale, Lambert Cadwalader, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770. 50" x 40". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, purchased for the Cadwalader Collection with funds contributed by the Mabel Pew Myrin Trust and the gift of an anonymous donor.)

Detail of the knee carving on the side chair illustrated in fig. 48.

Side chair attributed to the shop of Benjamin Randolph, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1765–1770. Mahogany. H. 37 1/2", W. 24 1/2", D. 21". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carving on the left stile of the side chair illustrated in fig. 48.

Detail of the carving on the left stile of the side chair illustrated in fig. 51. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair attributed to the shop of Benjamin Randolph, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1765–1770. Mahogany with tulip poplar. H. 41 1/2", W. 27", D. 15 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Detail of the knee carving on the side chair illustrated in fig. 54.

Side chair attributed to the shop of Benjamin Randolph, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770. Mahogany with unidentified secondary woods. Dimensions not recorded. . (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, purchased with the Fiske Kimball Fund, the John T. Morris Fund, and funds contributed by Marguerite and Gerry Lenfest, the Richard Chilton Foundation, H. Richard Dietrich Jr., Robert L. McNeil Jr., Fitz Eugene Dixon Jr., Mrs. E. Newbold Smith, Charlene Sussel, Anne H. and Frederick Vogel III, Andrew M. Rouse, and Dr. and Mrs. Robert E. Booth, 2003.)

Detail of the knee carving on the side chair illustrated in fig. 56. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair attributed to the shop of Benjamin Randolph with carving attributed to John Pollard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770. Mahogany with white oak. H. 36 3/4", W. (seat) 23", D. (seat) 19 1/8". The feet are restored. (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1908 [08.51.10]; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the knee carving on the chair illustrated in fig. 58. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the door frieze illustrated in fig. 8. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Benjamin Randolph, side chair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770. Mahogany with white cedar. H. 37", W. 22 5/8", D. 19 1/2". (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery.) This chair has Randolph’s label on a seat rail.

Benjamin Randolph (fig. 1) was the proprietor of one of the most successful cabinetmaking shops in Philadelphia during the 1760s and 1770s. That period witnessed the arrival of highly skilled immigrant carvers from Britain, the establishment of nonimportation agreements, and the building and furnishing of many grand houses by the city’s elite. Randolph’s surviving account book and receipt book reveal that he enjoyed the patronage of merchants, professionals, politicians, and prosperous tradesmen. The output of his shop was prodigious, and the purchases documented in his account book suggest that Randolph produced some of the most sophisticated and expensive furniture made in Philadelphia. Yet, despite his apparent prominence and the significant amount of documentation pertaining to his career, only a handful of objects have been convincingly linked to Randolph’s shop.[1]

The objective of this article is to summarize previous scholarship on Randolph and place it in the context of his account book and receipt book. A complete name index for the accounts has been compiled to aid scholars in applying this documentary evidence (see App. 1, 2). In addition to identifying Randolph’s patrons, his account book and receipt book provide information about his workforce, shop practices, and business dealings with other woodworkers. These documents also shed light on the complex and interconnected network of Philadelphia cabinetmakers and related tradesmen during the third quarter of the eighteenth century.

Randolph was born in 1737 and died in 1792. Although the names of his parents are not known, his lineage can be traced to the Fitz-Randolph family of New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Benjamin subsequently dropped the prefix from his name, abandoned his Quaker roots, and became an active member of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Philadelphia. He married Anna Bromwich in 1762 and began renting quarters from joiner John Jones by May of the following year. In November 1763 Benjamin and Anna inherited a large sum of money from her father’s estate. Two years later the couple moved into a house owned by William Milnor on Arch Street.[2]

In 1767 Randolph purchased the shop of Quaker carpenter Thomas Shoemaker on Chestnut Street and began advertising cabinet and chair work at the Sign of the Golden Eagle. Two years later, Randolph built a large shop and house on a town lot owned by James Hamilton, to whom he paid ground rent. Randolph remained in business at that location until he joined the Revolutionary War effort. In 1778 he sold his tools and remaining stock and retired to New Jersey. He died in 1791 and was buried at St. Paul’s.[3]

Inconclusive Documents and Tantalizing Clues

The primary sources for information about Randolph’s shop and business are his receipt book, account book, and miscellaneous papers in public and private collections. His receipt book is 229 pages long, arranged chronologically, and covers the years 1763 to 1777 (see App. 2). The entries record Randolph’s purchases and transactions with other Philadelphians, but most simply read “Received of Benjamin Randolph” and designate the amount in local currency. More informative is the account book—a bound, folio-size volume documenting transactions from October 1, 1768, through 1787. Several of the entries from 1768 are continued from an earlier account book, the location of which is unknown. Most of the pages in the surviving book are clearly numbered and indexed. The left side of the page lists the purchase or what was taken from the shop (i.e., cash, stock, lumber, unspecified goods), while the right side, designated “contra,” indicates how the client paid (i.e., cash, sundries, “to shop,” stock). Other pages set aside for general accounting include such headings as “Shop” (fig. 2), “Stock” (fig. 3), “Expense” (fig. 4), and “Sawmill.” Regrettably, several pages are missing from the book. The index, which was compiled at a later date, does not list pages 2, 5, 6, 11–14, 111–22, and 127–38. What remains, however, is the most complete record of any cabinet shop active in Philadelphia during this period.[4]

Because entries in Randolph’s account book are not specific, one cannot assume that every individual who paid him received furniture. Moreover, many of the entries record payments by Randolph for lumber, sundries, rent, work performed by employees, and investments in his many financial concerns. The accounts that do refer to furniture are identified by the phrases “to shop” and “to stock.” The former may refer to commission orders, whereas the latter may refer to finished goods for inventory or furniture that Randolph purchased from other cabinetmakers for retail.

Few of Randolph’s employees are identified by profession, but their role in his shop can be confirmed or inferred by the way certain accounts are written or by other supporting documentation. Several cabinetmakers other than those employed by Randolph are also mentioned, some of whom purchased lumber, stock, unspecified goods, or services. The independent cabinetmakers who purchased stock may have been acquiring furniture for resale or to satisfy orders within their respective shops.

Hercules Courtenay and John Pollard were among the most important artisans in Randolph’s shop. Courtenay had served his apprenticeship with renowned London carver and designer Thomas Johnson, whose publications One Hundred and Fifty New Designs (1758, 1761) and A New Book of Ornaments (1762) included some of the most advanced designs in the British rococo style. Although the identity of Pollard’s master remains unknown, the carving attributed to the Philadelphia émigré suggests that his training was comparable to that of Courtenay.[5]

The earliest reference to Courtenay in Philadelphia is his signature on the Nonimportation Agreement of 1765, but he may have come to the colonies earlier under an indenture with Randolph. On December 23, 1766, Randolph paid Jacob Chrysler £3.16.6 on Courtenay’s account. The following July, tailor Joseph Graisbury charged Randolph sixteen shillings for making Courtenay a “barygane coat.” If Courtenay was an indentured servant, his term probably expired by May 19, 1768, when he married Mary Shute. In the August 7, 1769, issue of the Pennsylvania Gazette, Courtenay advertised “all Manner of Carving and Gilding in the newest Taste, at his house between Chestnut and Walnut on Front Street.”[6]

The trusses, center tablet, and frieze appliqués on a chimneypiece from the parlor of Samuel Powel’s town house are the earliest carved details documented to Courtenay (figs. 5, 6). Between August and October 1770, Powel paid the carver a total of £60 for work in his “dwelling house.” These carved components indicate that Courtenay was extremely proficient and capable of working in the latest taste. The center tablet depicts Aesop’s fable “The Dog and the Meat.” Courtenay probably became acquainted with allegorical imagery during his apprenticeship in London. Thomas Johnson incorporated illustrations of Aesop’s fables in designs for architectural tablets and friezes published in One Hundred and Fifty New Designs.[7]

Although Randolph’s account book contains numerous references to Courtenay, Pollard received more credits and appears to have been the cabinetmaker’s principal carver during the late 1760s and early 1770s. Like Courtenay, Pollard eventually established his own shop. On February 22, 1773, the Pennsylvania Gazette reported that Pollard and his partner Richard Butts could provide “all manner of carving” at the Sign of the Chinese Shield. Other immigrant carvers are mentioned in Randolph’s account and receipt books, but there is little evidence that they consistently worked in his shop.[8]

No documented carving by Pollard is known, but strong circumstantial evidence suggests that he worked on some of the most important Philadelphia furniture and architectural woodwork in the rococo style. He almost certainly carved the remarkable scroll-foot sideboard table that descended in the family of John and Elizabeth (Lloyd) Cadwalader (see fig. 45) and furnished most of the architectural ornament for parlors from the Stamper-Blackwell House in Philadelphia and the Ringgold House in Chestertown, Maryland (figs. 7, 8). Both interiors have details taken from Johnson’s A New Book of Ornaments (figs. 9, 10).[9]

Occupational tax records suggest that Randolph had a very profitable business. The only other Philadelphia cabinetmakers with comparable assessments were Thomas Affleck and George Claypoole. Much of Randolph’s financial success appears to have come from investments in privateers, venture cargo, and “vendue” purchases, which are the largest transactions recorded in his account book. While most of Randolph’s clients spent less than £100 pounds in total (£10 was sufficient to purchase a significant piece of furniture), he paid £20,438.5.4 for goods at vendue on October 12, 1778, then spent the extraordinary sum of £105,770.15.5 outfitting the brig Argo as a “privateer.” The means by which Randolph financed such ventures remains a mystery, but his account book contains numerous references to ships and cargo assembled for export. Randolph’s account book does not describe the various lots of cargo, but many of his shipments probably included lumber. Randolph’s brother owned a sawmill, called Speedwell, in which Randolph ultimately became a partner, and numerous transactions in the account book refer to lumber. The lumber exported by Randolph probably included mahogany as well as indigenous woods, and some may have been shipped to England. In 1765 Randolph purchased 19,000 board feet of lumber from David Tryon. Although some scholars have cited that purchase as evidence that Randolph was involved in house carpentry, it is more likely that the lumber was intended as venture cargo. Destinations mentioned in his account book include London, Honduras, Jamaica, and Charleston, South Carolina, and many export entries mention the Philadelphia mercantile firm Willing and Morris. Some shipments may have included finished furniture, but only a handful of documents support that theory. In 1767 Randolph billed George Croghan for furniture “for yourself” as well as other pieces “to go abroad.” The cabinetmaker furnished packing cases for each piece intended for export. They may have been destined for a foreign port as venture cargo or for one of Croghan’s residences in this country.[10]

The account book of Philadelphia carpenter Thomas Neville supports the theory that Randolph enjoyed considerable success. During the 1760s and 1770s Neville oversaw the construction of houses for Captain John McPherson, the Cadwaladers, and other members of Philadelphia’s elite. The carpenter’s accounts record transactions with Randolph from December 1765 to February 1773. The most extensive charges were for work “in the best manner” installed in the cabinetmaker’s new house in 1769 and 1770. Among the architectural components provided by Neville were “77 yards 4 feet 2 ins. of Bilection wainscot,” “2 sets of Pillaster fluted with proper bases & Ionic Capitals, Ovilas round the chimney & mantle broak over truss’s,” “Ramp rails of mahogany, 1/2 rails, open pilasters & plinths against ye wall,” and “20 feet 8 ins. of moulding to form a Tabernacle frame finished with a Scrool like a Pediment & 8 knees Ovila round the chimney & 2 trusses.” Clearly, Randolph’s house was commensurate to a gentleman of means.[11]

While Cadwalader and McPherson usually paid Neville in cash, Randolph settled his debt with money, lumber, and “sundries.” In 1769 Neville credited Randolph’s account £8.4.10 for an easy chair and £1.10 for “Carving a pare of brackets for a dormer window.” In November of the following year, Neville billed Randolph for “Preparing 2 Ionic caps for carving” and in a separate entry recorded that three pounds of his debt to workman William Stephenson had been settled with a dressing table from Randolph’s shop. On March 26, 1771, Neville credited John Derry £15 for “the Workmanship of Benjamin Randolph’s frontis-Piece Door” and indicated that payment consisted of “a desk had of Benjamin Randolph.” Five months later, Neville credited Randolph’s account for “1/2 dozen mahogany chairs” and “2 clock cases delivered to William Huston.”[12]

Documentation and Attribution: A Sliding Scale

The only objects bearing Randolph’s label are a card table and a small group of seating furniture; however, all of these pieces can be used as benchmarks for attributing other work to his shop. The construction of the labeled side chair shown in figure 11 matches that of an unlabeled armchair (fig. 12), and both objects have knee carving by the same hand (figs. 13, 14). Based on these commonalities, it would be reasonable to assume that the armchair is also a product of Randolph’s shop. When comparing different forms, additional evidence is often required to support attribution. The tea table illustrated in figure 15 serves as a case in point. Its knee carving (fig. 16) is similar to that on the preceding chairs, but there are no structural parallels between the table and the seating forms. The table can, however, be attributed to Randolph by factoring in other pertinent information. Its feet are attributed to Hercules Courtenay based on their similarity to those on the card table illustrated in figure 17, and the card table is attributed to Courtenay based on its knee acanthus (fig. 18), which matches that on his documented mantel trusses from the parlor of Samuel Powel’s house (figs. 5, 19). In sum, the tea table has carving by two artisans known to have worked for Randolph; thus, the preponderance of evidence suggests that the table is from his shop.[13]

Several pieces of Philadelphia furniture have histories associated with Randolph patrons, but attributions based solely on provenance are highly conjectural, since consumers typically patronized more than one shop. Moreover, most of the entries in Randolph’s account book are not descriptive, and cost only hints at the type of work his shop may have performed for a given patron. A plausible representation of Randolph’s production can be posited, however, through formal analysis of objects associated with his clients and comparison of those pieces with furniture bearing his label. If a significant number of unmarked objects associated with Randolph’s clients have unifying structural, stylistic, and ornamental details, it would be reasonable to assume that they are products of his shop.

The cabriole-leg high chest illustrated in figure 20 bears the signature of Philadelphia cabinetmaker Isaac Barnet and a partially legible date that may be 1766 (fig. 21). Barnet’s name first appears in Randolph’s account book on May 5, 1770, and there are fifteen subsequent entries totaling £39.6 for work identified by the phrase “by shop” and “contra” recorded on March 9, 1771.[14]

The carving on the high chest is clearly by two different hands. All of the work on the upper case and the shell and appliqués on the center bottom drawer (fig. 22) are attributed to an anonymous artisan know today as the “Garvan high chest carver.” Research by Luke Beckerdite and Alan Miller suggests that this carver probably trained in Philadelphia and worked from the early to mid-1750s to the late 1760s. Nearly all of the case pieces carved by him are constructed in the same distinctive manner, which suggests that he was part of the workforce of a large cabinet shop rather than an independent tradesman. In contrast, the carving on the knees and skirt of the high chest (fig. 23) has affinities with work attributed to John Pollard. Barnet’s signature and date suggest that the high chest was made in Randolph’s shop shortly after Pollard arrived. The earliest reference to Pollard in Philadelphia is a December 1765 entry in Randolph’s receipt book.[15]

The construction of the high chest and the design and execution of the carving on its base link it to several other important Philadelphia case pieces, including a high chest base (figs. 24, 25) and a dressing table (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) possibly made en suite. Whereas all three of these objects may have come from the same cabinet shop, other case pieces with carving attributed to Pollard display significantly different construction techniques. He undoubtedly worked for several cabinetmakers and chair makers after establishing his own business in 1773.

While the high chest illustrated in figure 20 suggests that Randolph’s shop produced traditional Philadelphia forms, the furniture depicted on his trade card (fig. 26) attests to his familiarity with the latest British fashions. The desk-and-bookcase directly above the cartouche at the bottom was copied from plate 108 in the third edition of Thomas Chippendale’s Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1762) (fig. 27). The same Director engraving inspired the lower case design of a monumental desk-and-bookcase (fig. 28) that art historian Robert C. Smith attributed to Randolph in a 1971 article entitled “A Philadelphia Desk-and-Bookcase from Chippendale’s Director.”[16]

Subsequent scholars have questioned Smith’s attribution because he based his argument almost entirely on the imagery of Randolph’s trade card and failed to reconcile the fact that several Philadelphia cabinetmakers had access to Chippendale’s Director (the Library Company of Philadelphia had a copy of the 1754 edition). Although few have challenged the circa 1770 date that Smith later assigned to the piece, the integral pediment and Palladian design of the upper case suggest that the piece was made at least five years earlier. Most Philadelphia desk-and-bookcases and chest-on-chests from the 1770s have removable pediments. Similarly, the interiors of Philadelphia desks from the 1770s are typically quite severe, whereas the writing compartment of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 28 has boldly shaped serpentine drawers, a mirrored prospect door, and pilaster-fronted document drawers. Furthermore, all of the ornament on the desk-and-bookcase is by the Garvan high chest carver, whose career appears to have ended by the late 1760s (fig. 29).[17]

Although Smith’s attribution of the desk-and-bookcase to Randolph was a bit premature, evidence suggests that the art historian may have been correct. A bill of sale from Randolph to George Croghan documents the cabinetmaker’s production of very expensive furniture by 1765. At £30, the desk-and-bookcase commissioned by Croghan (fig. 30) cost more than twice as much as the most expensive example listed in James Humphreys Jr.’s Prices of Cabinet and Chair Work, published in Philadelphia in 1772. Although the entry for desk-and-bookcases included various options, the most expensive standardized model described in the price book cost £13 and had “doors . . . without glazing” and “carved work not to exceed 25s.” To reach a cost of £30, Croghan’s desk almost certainly had mirrored doors and elaborate carving. Given the probable date of the desk-and-bookcase and the extravagance of Croghan’s purchase, one is tempted to speculate that the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 28 may be the very one made for Croghan.[18]

Croghan’s wealth and prominence peaked during the years covered by Randolph’s bills. As Deputy Agent of Indian Affairs, he negotiated important peace treaties while speculating on land and profiting from trade networks made accessible through his position. He counted members of the illustrious Penn, Gratz, and Wharton families among his friends and business associates, and maintained houses in New York and Carlisle and Fort Pitt, Pennsylvania, where he was stationed.[19]

While neither Croghan’s name nor that of the mercantile firm that represented him during his residence at Fort Pitt appear in Randolph’s account book, itemized bills provide evidence of other furniture forms made in the cabinetmaker’s shop during the mid-1760s. No Philadelphia bracket clocks from that period are known, but Randolph’s shop clearly produced examples with such sculptural details as “cerebim head[s] carved.” At £15, Croghan’s “comade [commode] bureau table” must have been comparable to his desk-and-bookcase in form, materials, and ornament. One Philadelphia bureau table of commode, or serpentine, form is known, but it appears to date from the 1770s.[20]

Another desk-and-bookcase (fig. 31) with even stronger connections to Randolph supports the theory that his shop produced the example shown in figure 28. The former object’s integral pitch pediment, carved door moldings, mirrored door panels (now replaced with wood), and carved ogee-bracket feet represent later iterations of details found on the latter. The feet on these two pieces are nearly identical in design but were carved by different hands (figs. 32, 33). The carving on the prospect door and drawers in the writing compartment of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 31 is similar to that on the knees of a card table bearing Randolph’s label (figs. 34-36). With its fine acanthus leaves and thin, precisely carved scrolls, the desk is among the most delicate work associated with Pollard.

The top drawer of the desk section is inscribed “Nancy Emlen” and dated 1771, two years before the carver began working as an independent tradesman. Members of the Emlen family were among Randolph’s most important patrons. George Emlen Jr. had accounts totaling £262. 10s. and is the most likely person to have commissioned the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 31. His daughter Ann went by the nickname of Nancy and may have been responsible for the inscription on the desk. She would have been sixteen years old in 1771. On May 13 of that year Randolph debited “Miss Sally Emlen” £38.12, and four days later he received payment in cash. Her relationship to Nancy Emlen is not known, nor is the specific nature of her purchase.[21]

A high chest that reputedly descended in the family of William Turner of Philadelphia may also be a product of Randolph’s shop (fig. 37). Several transactions between the two men are recorded in the cabinetmaker’s account book between October 1765 and September 1773. On June 29, 1767, Turner married Mary King. Sixteen months later, he purchased “stock” from Randolph valued at £36.10.10. Given the fact that this entry appears to have been continued from an earlier account, it is possible that Turner commissioned the high chest shortly after his wedding.[22]

The carving on the high chest is closely allied with that on the Emlen desk-and-bookcase, labeled card table, and other furniture and architectural work associated with Pollard. Although the designs of their knee carving differ, the acanthus leaves on the chest (fig. 38) and table (fig. 36) have mirror-image turns as they approach the ankle. The tympanum appliqué on the chest (fig. 39) bears an even stronger resemblance to the carving from the Ringgold and Stamper-Blackwell parlors. Elements of the naturalistic festoon interwoven between the scrolls and Chinese columns of the appliqué are repeated on the garlands flanking both chimneypieces (fig. 40).

Provenance, patronage, and workmanship also support the theory that the pillar-and-claw tea table illustrated in figure 41 was made in Randolph’s shop. Family tradition and lineage suggest that the table’s original owner was Quaker merchant and patriot Clement Biddle. On March 6, 1775, he made a single purchase from Randolph totaling £5 (fig. 42). That amount appears to have been the going rate for a table like the one that descended in Biddle’s family. In 1769 Philadelphia cabinetmaker James Gillingham charged £5 for “1 mahog. Tea Table Scalloped Claw feet and leaves on knees.” The Philadelphia price book published three years later assigned a value of £5.15 to a tea table with claw feet, leaves on the knees, a scalloped top, and a carved pillar. While there were other furniture forms that cost the same amount, the timing and value of Biddle’s purchase suggest that it was the table shown in figure 41. Furthermore, the carving on the knees and pillar is attributed to Pollard (fig. 43). Although he had opened his own shop by 1773, Pollard continued to receive sizable payments from Randolph as late as August 1775.[23]

Vanguard of the Avant-Garde

A small group of objects associated with Randolph and Pollard represent the most stylistically advanced rococo furniture produced in colonial America. The easy chair illustrated in figure 44 descended in the family of Randolph’s second wife, Mary Wilkinson Fenimore, and was probably made in his shop during the mid- to late 1760s. The carving is attributed to Pollard based on technical and stylistic parallels with other work, particularly that on the Cadwalader sideboard table (figs. 45, 46) and architectural components from the Ringgold and Stamper-Blackwell parlors (fig. 46).[24]

With its mahogany arm faces, applied carved rails, and hairy-paw feet, the design of the easy chair is unique among known Philadelphia examples. The mask on the front rail is an urban British detail likely introduced by either Pollard or Courtenay. As one might expect, the earliest work associated with these artisans shows the strongest reliance on English design. By the late 1760s both carvers had begun assimilating details of the Philadelphia vernacular.[25]

During the 1760s and 1770s Randolph maintained accounts with several Philadelphia upholsterers, including Plunkett Fleeson, Samuel How, Thomas Lawrence, William Martin, John Webster, and John Read. Much of the cabinetmaker’s business went to Fleeson, whose shop at the “Sign of the Easy Chair on Chestnut Street above 3rd Street” was just a few steps away. In March 1767 Fleeson charged George Croghan five pounds for upholstering “2 mahogany French chair frames,” which were most likely not the “pair [of] mahogany armchairs” Randolph had sold Croghan a month earlier.[26]

The Cadwalader sideboard table (fig. 45) is the most elaborately carved object that can be linked to Randolph’s shop. Its basic form and the reclining figure in the center were taken from a design for a pier glass and table illustrated on plate 152 of Chippendale’s Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1762) (fig. 47). John Cadwalader’s waste book notes that on October 10, 1769, he reimbursed his brother Lambert £94.15 for “B. Randolph[s] acct for Furniture” and £30 for “2 marble Slabs etc. had of C. Coxe.” Randolph’s account book contains only passing mention of John Cadwalader and his brother and agent Lambert, but the entry corresponding to the £94.15 purchase was probably on one of the pages removed from that document. Luke Beckerdite, Leroy Graves, and Alan Miller have speculated that the table dates from the mid- to late 1760s, because its design and carving show no concession to prevailing Philadelphia styles. If they are correct, then the table is almost certainly from Randolph’s shop. His account book suggests that Pollard was a full-time employee during that period. The carver received £180.24 for work performed between November 1768 and September 1769. The last payment occurred only ten days before the entry in Cadwalader’s waste book.[27]

Although it is impossible to determine the cost of the sideboard table, the £94.15 payment to Randolph may have been sufficient for both its carved frame and a set of commode-seat side chairs that descended in the Cadwalader family (fig. 48). This seating appears to have been completed by September 1, 1770, when Charles Willson Peale received payment in full for his portrait of Lambert Cadwalader, depicted with his hand resting on one of the chairs (fig. 49). That date indicates that the chairs were the genesis of a much larger suite of furniture with related carving designs that John and Elizabeth Cadwalader commissioned from Philadelphia cabinetmaker Thomas Affleck later in the year.[28]

The splats of the Cadwalader chairs may have been inspired by designs for “Ribband Back Chairs” illustrated on plate 15 in the third edition of Chippendale’s Director (1762). As Beckerdite and Graves have noted, the acanthus leaves on the rails and knees are by the same hand that carved the side chairs bearing Randolph’s label (figs. 13, 50). Because aspects of the carving on Cadwalader’s seating also relate to that associated with both Pollard and Courtenay, the aforementioned scholars believe that the commode-seat chairs were produced in Randolph’s shop and probably accounted for the £94.15 expenditure recorded in John Cadwalader’s waste book.[29]

A chair that descended in the family of Randolph’s second wife (fig. 51) also supports the theory that his shop produced the commode-seat examples (fig. 48). All of these chairs have rear stiles with acanthus leaves similar to those on trusses that Courtenay carved for the mantel in Samuel Powel’s parlor (figs. 5, 52, 53). With its scroll feet and carved seat rails, the chair illustrated in figure 51 conforms to contemporary London taste more closely than its paw-foot counterparts (fig. 48).

Because they shared the same history of descent, Samuel Woodhouse speculated that the chairs illustrated in figures 48, 51, and 54 were samples that Randolph kept on display at his shop. Although that theory is refuted by roman numerals on certain examples (indicating their number in a set), these extraordinary seating forms are important in connecting other work to Randolph’s shop. The knee carving on the chair illustrated in figure 54 is closely related to that on a pair of card tables and a set of side chairs with trapezoidal seat frames (figs. 55-57) owned by John and Elizabeth Cadwalader. Like the couple’s commode-seat chairs (fig. 48), this suite is not identified in any known bills or accounts.[30]

The backs of the trapezoidal-frame chairs match those on two elaborate side chairs from a set of at least eight (fig. 58). As Philip Zimmerman has noted, the backs of all these examples have comparable husk and acanthus ornament that appears to have been laid out using the same pattern. The carving on the knees and seat rails of the chairs represented by figure 58 is attributed to Pollard based on its relationship to architectural work in the Ringgold and Stamper-Blackwell parlors (figs. 8, 9, 59, 60). The front and side rails are made of oak and have mahogany laminates below. This two-part structure has an experimental quality recalling the construction of the easy chair illustrated in figure 44.

Although the strength of individual attributions advanced for the avant-garde furniture mentioned above varies, when considered as a group the design, construction, carving, and provenances of these objects strongly suggest that all are products of Randolph’s shop. His account book and surviving bills and receipts indicate that he maintained a workforce capable of manufacturing furniture in the latest London styles as well as pieces reflecting more traditional Philadelphia tastes. As the side chair illustrated in figure 61 suggests, he also offered furniture at a variety of price points ranging from astonishingly expensive objects like the desk-and-bookcase commissioned by George Croghan to simple forms suitable for export. The ability to accommodate a wide variety of tastes and budgets was key to Randolph’s success as a cabinetmaker.

Insights into Randolph’s shop can be inferred from omissions in the account book as well. A tea table in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art has been previously attributed to Randolph with reasonable assurance based in a bill of sale documenting Vincent Loockerman’s £38.8 purchase on October 26, 1774. However, current scholarship suggests that the carving is by Nicholas Bernard and Martin Jugiez, and the account book indicates that Bernard and Jugiez had no significant connection to the shop. Loockerman clearly patronized Randolph’s shop, but his purchase probably did not include this table. Loockerman, like most other wealthy Philadelphia consumers, purchased furniture from numerous shops.[31]

Beatrice B. Garvan discovered Randolph’s folio account book for the years 1768–1787 in the New York Public Library, catalogued as “Philadelphia Merchant’s Account Book.” Among the many illustrious names that appear in Randolph’s accounts are those of George and Martha Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and John Penn. George paid the cabinetmaker for Martha’s lodging during the spring and summer of 1776 (“Sundry bills pd. by Mrs. Washington at Philadelphia,” 1776, George Washington Papers, 5th ser., vol. 24: “Vouchers and receipted accounts,” Library of Congress). Jefferson also stayed with Randolph when he arrived in Philadelphia in July 1775, and again when he returned the following May. During his stay, Jefferson purchased from Randolph the lap desk on which he drafted the Declaration of Independence. According to Jefferson, “[the desk] . . . was made from a drawing of his own, by Ben. Randall, cabinetmaker of Philadelphia with whom he first lodged on his arrival in that city” (Susan Stein, The Worlds of Thomas Jefferson [New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1993], pp. 364–65).

Several men named Benjamin Fitz-Randolph were born in eastern Pennsylvania and New Jersey between 1721 and 1737. The marriage and working dates of the man who is the subject of this article suggest that he was born ca. 1737. Building on the work of Samuel Woodhouse Jr. and other scholars, Beatrice B. Garvan developed a concise but thorough biography of the cabinetmaker (Beatrice B. Garvan, “Benjamin Randolph,” in Philadelphia: Three Centuries of American Art [Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1976], pp. 110–11; Samuel Woodhouse Jr., “Benjamin Randolph of Philadelphia,” Antiques 11, no. 5 [May 1927]: 336–71; and Samuel Woodhouse Jr., “More about Benjamin Randolph,” Antiques 17, no. 1 [January 1930]: 21–25). The account book records that John Penn made a single purchase from Randolph’s shop, spending £10 on September 30, 1773, and paying for his purchase in cash on October 9 of that year. Penn left Philadelphia for London in 1771 but returned in 1773, and was appointed governor on August 30. A sofa with John Penn provenance, now at Cliveden of the National Trust, corresponds to the description of the sofa costing that amount in James Humphrey’s Prices of Cabinet and Chair Work but has traditionally been attributed to cabinetmaker Thomas Affleck.

Randolph’s shop was adjacent to property owned by joiner Henry Mitchell (Garvan, “Benjamin Randolph,” pp. 110–11). Randolph advertised the sale of his tools and remaining stock in the November 10, 1778, issue of the Pennsylvania Packett.

William Macpherson Hornor Jr. alluded to the existence of “original manuscript account books and a receipt book” as the basis for attributing furniture to Thomas Affleck in his Blue Book Philadelphia Furniture (Philadelphia: by the author, 1935), p. 73. The receipt book may have been the one maintained by Affleck’s patron David Deschler now in the Marion Carson Collection, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

For more on Courtenay and Pollard, see Beatrice B. Garvan, “Hercules Courtenay” and “John Pollard,” in Three Centuries of American Art, pp. 111–12; Luke Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops, Part III: Hercules Courtenay and His School,” Antiques 131, no. 5 (May 1987): 1044–63; and Luke Beckerdite and Leroy Graves, “New Insights on John Cadwalader’s Commode-Seat Side Chairs,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2000), pp. 152–60. For Courtenay’s apprenticeship to Johnson, see Morrison H. Heckscher, American Furniture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, vol. 2, Late Colonial Period: The Queen Anne and Chippendale Styles (New York: Random House for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1985), p. 25. Randolph’s account book also mentions James Reynolds, a British-trained carver who immigrated in 1766. Reynolds was credited £8 under Andrew Doz’s account with Randolph in 1769. Ten years later, the carver received a £6.14 credit on Randolph’s shop page. Although Reynolds had limited interaction with Randolph’s shop, he received considerable patronage from Philadelphia cabinetmaker Thomas Affleck. For more on Reynolds, see Luke Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops, Part I: James Reynolds,” Antiques 125, no. 5 (May 1985): 1120–33. The prolific carving partnership of Nicholas Bernard and Martin Jugiez is conspicuously absent from Randolph’s account book. The cabinetmaker’s receipt book contains one reference to their carving firm, but there is no evidence that Bernard and Jugiez did work for Randolph. For more on their carving firm, see Luke Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops, Part II: Bernard and Jugiez,” Antiques 128, no. 3 (September 1985): 498–513; and Luke Beckerdite and Alan Miller, “A Table’s Tale: Craft, Art, and Opportunity in Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia,” American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. 2–45. The only other carvers mentioned in Randolph’s account book are Bryan Wilkinson, Richard Butts, and James Wilson. For more on Wilkinson, see Beckerdite and Miller, “A Table’s Tale,” p. 5. On February 22, 1773, the Philadelphia Packett reported that “[John] Pollard and [Richard] Butts [would] . . . undertake . . . all manner of Carving in the House, Cabinet, Coach, and Ship way (Alfred Coxe Prime, comp., The Arts and Crafts in Philadelphia, Maryland, and South Carolina, 1721–1785: Gleanings from Newspapers, 2 vols. [1929; reprint, New York: Da Capo Press, 1969], 1: 224). Randolph’s account book refers to Wilson on pages 1, 44, and 56 in 1768. Six years earlier, Philadelphia cabinetmaker George Claypoole paid Wilson for “carving 8 table feet” during the period 1753–1758 (James Wilson to George Claypoole, April 1762, box 2, folder 15, Marion Carson Collection, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress). It is difficult to assess the role Randolph played in the day-to-day operation of his shop. Period documents usually refer to him as a cabinetmaker, but when he signed a deed book in 1781 he identified himself as a carver and gilder (Woodhouse, “Benjamin Randolph of Philadelphia,” p. 35). Regrettably, it is impossible to determine whether Randolph actually worked as a carver and gilder or contracted it to independent specialists. The names of other carvers likely appear in the account book, but they are as yet unidentified.

Garvan, “Hercules Courtenay,” p. 112; Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops, Part III,” pp. 1044–46; and Beckerdite and Graves, “New Insights,” p. 156.

Samuel Powel Ledger, 1760–1793, p. 129, Library Company of Philadelphia, as cited in Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops, Part III,” p. 1048. For more on the use of Aesop’s fables as design sources, see Richard H. Randall Jr., “Designs for Philadelphia Carvers,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1996), pp. 57–62. Aesop’s fable “The Dog and the Meat” also appears on the front of a ten-plate stove marked “H. W Stiegel / 1769 / Elizabeth Furnace.” The patterns for the plates of the stove were undoubtedly carved by Courtenay.

Beckerdite and Graves, “New Insights,” pp. 152–60. Pollard was listed as a joiner in the Proprietary Tax in 1769. The apparent error in describing his trade probably stems from the fact that he was working for Randolph in that year (Garvan, “John Pollard,” p. 114).

Beckerdite and Graves, “New Insights,” pp. 153, 156–58. Randolph’s account book contains an August 5, 1771, debit entry under Ringgold’s name, “To Shop £23.6.6” (p. 144). The carving attributions presented in this article are largely based on research by Luke Beckerdite and Alan Miller.

For 1785 occupational tax figures, see Hornor, Blue Book, pp. 317–21. Randolph’s expenses for outfitting the Argo are listed in his account book, pp. 245, 247. Garvan cited Randolph’s purchase of large parcels of lumber as evidence that he engaged in house joinery. (Garvan, “Benjamin Randolph,” p. 111). Although his shop clearly did architectural carving, Randolph’s lumber purchases were most likely intended for resale. For Randolph’s bill to Croghan, see Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Cadwalader Collection, Series IV, Box 2, Folder 6. Croghan had several residences, and during this period was moving from Pennsylvania to New York. The furnishings may have been intended for his new home on Otsego Lake, New York, but he did not leave for Otsego until 1769, and then it was to supervise construction. The distinction between “for yourself” and “to go abroad” suggests that the furniture was destined for a foreign port, perhaps as venture cargo. See Albert T. Volwiler, “George Croghan and the Development of Central New York, 1763–1800,” Quarterly Journal of the New York State Historical Association [New York History] 4, no. 1 (January 1923): 21–40.

Thomas Neville Account Book, NA 733 W47 MF, pp. 164–70, University of Pennsylvania Library, Philadelphia. The author thanks Alexandra Kirtley for bringing the account book to his attention. Randolph and Neville clearly disagreed about their accounts. On February 27, 1773, Neville credited Randolph “the Ballence of his Acct. as Alo’d by the Court & jury in ye 3rd of this instant 180.19.9” (p. 184).

Ibid., pp. 135, 134, 172, 178, 180. Stephenson and Derry do not appear in Randolph’s account book, as they were presumably recorded on Neville’s account.

For more on the labeled Randolph side chairs, see Philip D. Zimmerman, “Labeled Randolph Chairs Rediscovered,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1998), pp. 81–99. An armchair sold by C. L. Prickett and Sons was probably made in Randolph’s shop and reputedly descended with a bill of sale. It is illustrated and discussed in Antiques 60, no. 3 (September 1951): 178–79. The article refers to a May 5, 1767, bill from Randolph for “an armed chair” valued at £4.11 that “[came] down in the family with [the chair].” In comparison, George Croghan paid Randolph £5 each for a pair of armchairs that same year (Martha H. Willoughby, “Discoveries from the Field: Randolph Chairs?” Catalogue of Antiques and Fine Art 5, no. 1 [Spring 2004]: 150–51). Another chair bearing Randolph’s label is from a set that reputedly descended from Robert Kennedy of Washington’s Crossing, New Jersey. Randolph’s account book mentions a Robert Kennedy, but only in connection to minor lumber and “sundry” accounts (Randolph Account Book, pp. 40, 43, 218). If Kennedy was the first owner of these chairs, the set probably predates the account book. Randolph may have begun referring to his shop and Chestnut Street address on labels in 1767. The label on this chair reads: “All Sorts of Cabinet and Chairwork Made and Sold by Benjn. Randolph at the Sign of the Golden Ball in Chestnut Street Philadelphia” (Christie’s, Important Americana, New York, October 21, 1989, lot 402). The chairs with the Kennedy history differ considerably from the majority of seating documented and attributed to Randolph’s shop and are the only examples with shells on the knees and this splat design. Kennedy’s chairs may have been made by another furniture maker, then labeled by Randolph and retailed through his shop. With its many references to other cabinetmakers and chair makers, Randolph’s account book suggests this possibility. He used furniture as payment for goods and services provided by Thomas Neville (Neville Account Book, pp. 134–35).

Randolph Account Book, p. 124. Barnet may have served his apprenticeship in Randolph’s shop and continued to work as a journeyman after his term ended. If so, that could explain why Barnet’s name appears on the high chest, which clearly predates the entry for Barnet in Randolph’s account book. There would have been no reason for Randolph to record an apprentice’s name, since young men in training typically received no payment. Barnet may have begun working as a journeyman in 1770, and he received most of his payments in cash. On March 14, 1771, he received £1.15.9 “in full of all accounts”(Benjamin Randolph Receipt Book, p. 139).

Randolph’s shop was producing high chests by 1766. In September of that year, Randolph charged Isaac Zane £22 for a mahogany high chest and matching dressing table (Receipt from Benjamin Randolph to Isaac Zane, Box 3, Folder 30, Marion Carson Collection, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress). Randolph Receipt Book, p. 57.

Robert C. Smith, “A Philadelphia Desk-and-Bookcase from Chippendale’s Director,” Antiques 107, no. 1 (January 1973): 129–35. On November 10, 1778, the Pennsylvania Packett reported: “To be SOLD at Public Vendue, On Thursday the nineteenth instant, at the Ware Room of Benjamin Randolph, in Chesnut street, A QUANTITY of Carvers and Cabinet makers Tools, consisting of planes, saws, gouges, chisels, work benches, &c. &c. with a variety of carved mahogany brackets, figures, carved and gilt girandoles, with sundry other furniture of different kinds, and a small quantity of mahogany.” The reference to “figures” suggests that Randolph’s shop produced sculptural busts like the one on the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 28.

Smith, “A Philadelphia Desk-and-Bookcase.” The author thanks Luke Beckerdite and Alan Miller for their thoughts on the working dates of the Garvan high chest carver and the changes in his style over time.

The Humphreys price book is in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The early history of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 28 is opaque and provides no links to George Croghan. The only owner identified to date was Rev. Edward Craig Mitchell (1836–1911) of Philadelphia and St. Paul, Minnesota (J. Michael Flanigan, American Furniture from the Kaufman Collection [Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1986], pp. 90–93).

Volwiler, “George Croghan and the Development of Central New York,” pp. 21–40.

Hornor, Blue Book, p. 96, pl. 116. The 1772 price book lists a “commode dressing table, with four long drawers” valued at £14 and a “Bureau Table” with prospect door and quarter columns valued at £8.10. For a desk with a commode front and slant lid, see Parke Bernet Galleries, Property of the Estate of the Late Reginald M. Lewis, New York, March 24 and 25, 1961, lot 246.

For George Emlen Jr.’s purchases, see Randolph Account Book, pp. 15, 38, 178, 218, 228. Sarah Emlen’s purchases totaled £92.6 (ibid., pp. 124, 154, 247). For Sally Emlen’s purchases, see ibid., p. 143. Randolph records Pollard’s presence in the shop throughout this period, including several times in 1771, with accounts for £70.17 listed on the shop page under the date October 14, 1771 (p. 153).

Randolph Account Book, p. 31. Turner paid for his purchases with “sundries” in 1773. There is uncertainty about the exact line of descent. Alternative accounts of the history indicate that William Turner married either Mary King or Sarah King. The probable line of descent is as follows: William Turner to his daughter Abby Ann Turner (unmarried) to her niece Abby Ann King Turner (second wife of Rev. Peter Van Pelt) to Edward and Ellen Van Pelt. The chest was purchased by Howard Reifsnyder in 1921, then acquired at his sale by Henry Francis du Pont in 1929.

Randolph Account Book, p. 181. Biddle married his second wife, Rebekah Cornell, in 1774. For the provenance of the Biddle tea table, see Christie’s, Important American Furniture, Silver, Prints, Folk Art, and Decorative Arts, New York, January 18–19, 2001, lot 119. Harold E. Gillingham, “Benjamin Lehman, a Germantown Cabinetmaker,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 54 (1930): fig. 2, as cited in Morrison H. Heckscher and Leslie Green Bowman, American Rococo, 1750–1775: Elegance in Ornament (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art and Harry N. Abrams, 1992), p. 196. Randolph Account Book, p. 207.

The easy chair illustrated in figure 44 is one of six so-called sample chairs identified by Samuel Woodhouse Jr. who attributes them to Randolph in Woodhouse, “Benjamin Randolph of Philadelphia,” pp. 33–38.

This easy chair is the only American example with hairy-paw back feet.

The 1772 Philadelphia price book indicates that a mahogany easy chair with “claw feet and leaves on knees” cost £3.5 indicating that the easy chair for which Thomas Neville credited Randolph £8.4.10 in 1769 was probably already upholstered (Neville Account Book, p. 135).

For more on the attribution of the pier table to Pollard and its derivation from the Director engraving, see Beckerdite and Graves, “New Insights,” pp. 156–60. Nicholas B. Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur in Philadelphia: The House and Furnishings of General John Cadwalader (Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1964), p. 22. According to Wainwright, Randolph furnished £252.16.1 worth of architectural carving for John and Elizabeth Cadwalader’s town house (pp. 20–21).

For more the attribution of the commode-seat chairs to Randolph, see Beckerdite and Graves, “New Insights,” pp. 152–61. According to the two scholars:

The saddle-seat chairs were clearly part of a unified decorative scheme that included the suite made by Affleck and that extended to the architectural carving and fabrics used in each of Cadwalader’s principal rooms. Bills pertaining to the textile furnishings in Cadwalader’s house shed light on the probable number, upholstery, and placement of the saddle-seat chairs. On October 18, 1770, Philadelphia upholsterer Plunkett Fleeson charged Cadwalader £13.13 for “covering thirty-two chairs over rail finish’d in canvis.” The following January, the upholsterer made seventy-six Saxon blue French check cases with blue and white fringe for these chairs and others that Cadwalader had either purchased or inherited from his father-in-law. The commode-seat chairs were subsequently fitted with covers made of blue and yellow silk damask that Cadwalader ordered from London merchants Rushton & Beachcroft. In January 1772, Philadelphia upholsterer John Webster billed Cadwalader £18.7.10 for making the curtains for four windows and for upholstering twenty chairs and three sofas with these fabrics. A subsequent entry in Cadwalader’s Waste Book provides additional information on Webster’s work, noting that the payment was for “Curtains in [the] front & back Rooms, Covers to Settees & Covers to Chairs in front & back Rooms.” The curtains and covers in the front room were blue and the ones in the back parlor were yellow to match the colors of each room’s walls and Wilton carpets. An “Inventory of Contents Remaining in [the] Cadwalader House” taken in 1786 lists two blue damask window curtains, a blue damask settee cover, ten blue damask chair covers, two yellow silk damask window curtains, ten yellow silk damask chair bottoms, and “1 cover of a settee for d” (the bills from Fleeson, Webster, and Rushton & Beachcroft [the London merchants who provided the silk fabrics, fringe, and tape] are reproduced in Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur, pp. 40–41, 59, 61). Cadwalader owned a second suite of furniture with hairy paw feet and straight rails (see fig. 56). The chairs and matching card tables in the second suite may have sat in the small front parlor, which had green walls. Assuming that there were twelve chairs in this suite and twenty saddle-seat chairs, that would account for the thirty-two that Fleeson covered over the rail. Although chair “bottoms” could be interpreted as slip seats, this term probably referred to slipcovers. The use of two terms in the inventory may result from its having been taken by John Cadwalader’s sister Rebecca and his brother-in-law Samuel Meredeth. Three copies of the inventory survive, and they vary slightly. The 1786 inventory also lists one mahogany dining table, one marble slab [table], and one card table in the “small front parlor,” one marble slab [table], one card table and ten mahogany chairs, in the “back parlor,” one large settee, one small settee, one card table, ten mahogany chairs in the “front parlor,” one small settee in the “entry” on the second floor, six mahogany chairs with chintz “furniture” in the “back chamber” on the second floor, six mahogany “carpet bottom” chairs in the “front chamber” on the second floor, two old chairs and six mahogany chairs in the “front room” on the third floor” and two green covers for card tables, 1onelarge easy chair, and ten old mahogany chairs “many broke” in the front garrett on the third floor. (p. 161)

Beckerdite and Graves, “New Insights,” pp. 153–59.

Woodhouse, “Benjamin Randolph of Philadelphia,” pp. 33–38. Beckerdite and Graves have speculated that the card tables and chairs with trapezoidal seats may have been used in the small front parlor of the Cadwaladers’ house (see n. 28 above). For a different viewpoint on the Cadwalader furniture, see Phillip Zimmerman, “A Methodological Study in the Identification of Some Important Philadelphia Chippendale Furniture,” Winterthur Portfolio 13 (1979): 193–208. The matching card tables from the suite including the side chair shown in fig. 56 are in the Winterthur Museum and in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Beatrice B. Garvan, cat. no. 101 in Three Centuries of American Art, pp. 127–28. Randolph Account Book, p. 211. Loockerman paid for his purchase in cash on November 26, 1774. For more on Bernard and Jugiez, see Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops, Part II: Bernard and Jugiez”; and Beckerdite and Miller, “A Table’s Tale.”