Archaeological excavation at Jamestown, Virginia. Overview (looking west) of area opened up on the banks of the James River on Jamestown Island that revealed traces of the fort erected by the English in 1607. (Courtesy, Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities; photo, David M. Doody.)

APVA archaeologists excavating artifacts from what proved to be a cellar, possibly to a blockhouse of James Fort, that was filled ca. 1610. (Courtesy, Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities.)

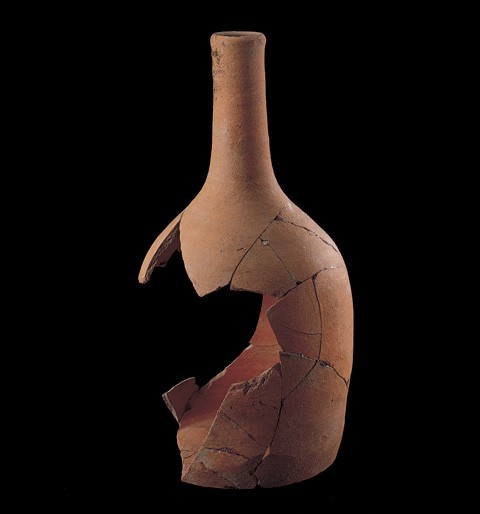

Detail of a London distilling flask as found in the course of excavation of the ca. 1610 cellar. (Courtesy, Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities.)

Distilling flask, London, 1600–1610. Unglazed earthenware. H. 15". (Courtesy, Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The mended flask as seen in fig 3. One of a number of London coarsewares that have been recovered from James Fort’s earliest contexts. Distilling flasks are frequently found in London contexts dating to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Most often associated with metal-working sites, these flasks are believed to be cucurbits, or the bottom elements of stills.

Bouquet of Flowers in Glass, Christoffel van den Berghe, 1617. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, John G. Johnson Collection.)

Dish, China, 1613. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 8 1/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) An example of Chinese porcelain recovered from theWitte Leeuw. The central medallion contains a grasshopper on a rock and a peony. The border is decorated with alternating flowers and symbols.

Wine cup, China, ca. 1600. Hard-paste porcelain. H. 1 11/16". (Courtesy, Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dish, Portugal, ca. 1660. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 14 5/8 ". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) An example of a Portuguese enameled dish painted in blue with manganese outlines of the Wan-Li-style decoration. Large dishes of this type have been excavated at Jamestown. A similar dish with this rabbit motif was excavated from another seventeenth-century site near Jamestown.

Bowl section, Portugal, ca. 1640. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 2 9/16 ". (Courtesy, City of Newport News, Virginia, Boldrop Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Shallow dish fragment, Portugal, ca. 1640. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, The National Park Service, Colonial Historical National Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dish, Portugal, 1620–1640. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 9". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dish fragment, Portugal, 1630–1650. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 8". (Courtesy, Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, George Sandys Site Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Flask, northern France, 1600–1610. Unglazed earthenware. H. 8". (Courtesy, Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Example excavated from the James Fort site.

Le Dessert de Gaufreetes, Lubin Baugin, ca. 1610–1663. (Courtesy, Louvre; photo, Gerard Blot.) The wicker-covered bottle in this painting is probably made of glass but it reflects the same shape as wickered Martincamp flasks.

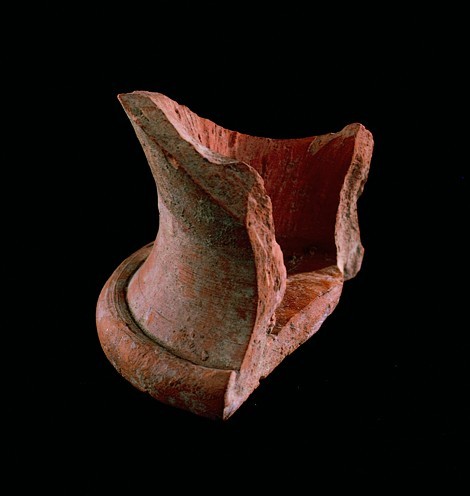

Costrel base fragment, northern Italy, 1600–1640. (Courtesy, The National Park Service, Colonial Historical National Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Costrel, northern Italy. Slipware. H. 11º". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Still Life with Glasses and Bottle, Sebastian Stosskopf, 1641–1644. (Courtesy, Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen Zu Berlin, Preussischer Kulturbesitz; photo, Jorg P. Anders.) The northern Italian slipware costrel, standing next to a wicker-encased glass bottle, has a cord handle looped through integral lugs.

Bowl fragment, northern Italy, 1625–1635. Slipware. H. 4 3/4". (Courtesy, Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Example excavated from the James Fort site.

Bowl, northern Italy, 1620–1640. Slipware. D. 9 3/4". (Courtesy, The National Park Service, Colonial Historical National Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Reverse of the bowl illustrated in fig. 19. (Courtesy, The National Park Service, Colonial Historical National Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tazza fragment, Montelupo, Italy, 1620–1640. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, The National Park Service, Colonial Historical National Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

A replica of the Montelupo tazza or footed bowl represented by the archaeological fragment shown in fig. 21. H. 7". (Courtesy, Michelle Erickson; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dish, Montelupo, Italy, 1620–1640. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 12". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dish, Montelupo, Italy, 1620–1640. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 12". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dish fragment, Montelupo, Italy, 1630–1650. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, the Reverend Richard Buck Site Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Reverse of the dish illustrated in fig. 25. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Le tombeau de Maître Andre, Claude Gillot, 1673–1723. Oil on canvas. (Courtesy, Louvre; photo, Eric Lessing.)

A Kitchen Scene, Floris van Schooten, ca. 1620–1630. (Public domain, Heinz Family Collection.) The painting shows Raeren stoneware jugs with the Seven Electors motif hanging in the background. The jugs are mounted with silver or pewter lids which increase their value and reveal their high status among seventeenth-century tablewares.

Jug, Raeren, 1600–1620. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 10 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jug fragment, Raeren, 1600–1610. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This excavated example contains a portion of a mid-girth Seven Electors motif.

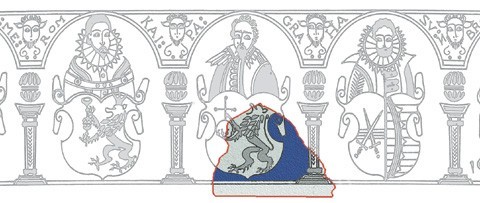

Photo illustration. (Courtesy, Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities; graphic, Jamie May.) If the coat of arms on the Raeren jug from James Fort illustrated in fig. 30 had been complete, it would have depicted the bust of the count palatine of the Rhine behind his coat of arms. In 1613 King James’s daughter, Elizabeth Stuart, married Frederick V, the elector palatine and successor to Frederick IV, who is represented on the jug from James Fort.

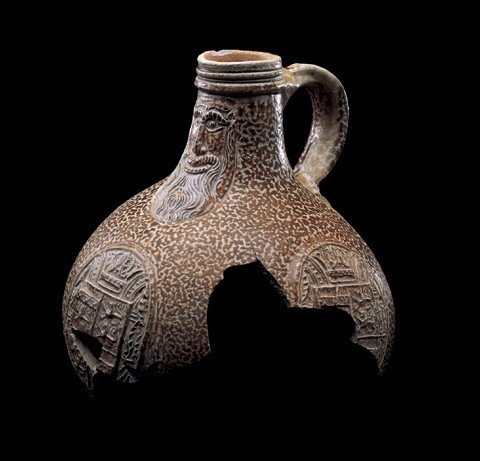

Bottle, Frechen, Germany, ca. 1600. Stoneware. H. 8". (Courtesy, Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Example excavated from the James Fort site.

Soldiers in a Tavern, Gerald Terborch, 1658. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, John G. Johnson Collection.) This painting depicts a Bartmann bottle standing by the feet of a soldier who is drinking beer from a glass. These durable stoneware containers quickly evolved in status to decanters that could be used at the table in conjunction with drinking vessels made of other materials.

Bottle, Frechen, Germany, 1605. Stoneware. H. 9 1/4". (Guthman collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) An antique example of a single medallion Bellarmine, dated 1605.

Detail of medallion on the bottle illustrated in fig. 32. (Courtesy, Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities; photo, Beverly Straube.)

Archaeologists love to find ceramics on their sites and, luckily, because of the nature of clay vessels, they are usually not disappointed. Ceramic material, being of the earth, seems to form a symbiotic relationship with the soil that surrounds it. Unlike iron objects that rust away, glass materials that devitrify into splinters, and bone and wood artifacts that rot into mush, pottery endures. The sherds may break apart and get smaller as nature or people move them around, the glazes may begin to separate from the fabrics, but the wares will still be identifiable.

Ceramics have been used throughout history to ship, store, prepare, and consume food and beverage. In addition, they have functioned to provide heat, light, and other day-to-day comforts. And they were often used as a sign of social status.

The use of pottery in everyday life subjects it to frequent breakage and disposal, but its relative durability ensures that the fragments survive. Ceramics, therefore, are one of the most important classes of artifacts excavated by archaeologists. They can reveal information about date, status, function, trading patterns, changes in eating or drinking habits, and migrations of populations.

This said, it must be mentioned that ceramics are all but invisible in the historical record. They are rarely listed on probate inventories and, if so, only in general terms. Shipping and customs records seem interested in ceramics only secondarily, as containers of goods. Indeed, there are no references in English importation records of pottery being the sole or most important cargo. It is up to archaeology to help fill the gaps in our knowledge.

The Jamestown Rediscovery excavations in Jamestown, Virginia, have uncovered more than twenty thousand fragments of pottery since 1994 (fig. 1-4). Most of these sherds are from contexts within what was known as “James Fort.” Built by the 104 men and boys who arrived from London in May 1607, James Fort is the site of the earliest permanent English settlement in the New World. It is where the United States of America began. What more fitting place to study some of the earliest European ceramics used in America?[1]

The Jamestown colonists did not attempt pottery production in Virginia until the 1630s. Before that time they had to rely on vessels produced elsewhere. Besides England, the countries of origin represented in the Jamestown Rediscovery ceramic assemblages are China, France, Germany, Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain. These countries were not directly trading with Jamestown, however.

From its inception until 1624, the colony of Virginia was under the control of the Virginia Company of London. This group of entrepreneurs, made up largely of London merchants and craftsmen, supplied the settlement out of London whenever possible, most often for their own enrichment. The Virginia Company provided the household ceramics for Jamestown beyond those brought by the individual colonists as part of their personal possessions. As such, the diversity of Jamestown’s ceramics reflects the cosmopolitan nature of London in the early seventeenth century.

What can these silent but durable, sometimes colorful, objects tell us about America’s colonial past? Why, for instance, is Italian comedic theater represented at Jamestown? How does a small Chinese porcelain vessel link Jamestown, Virginia, with another Jamestown island off the African coast, and thereby to the Dutch trading monopoly with the East? What does a German count, who was instrumental in the political play foreshadowing the Thirty Years’ War, have to do with the Virginia settlement?

These and other questions will be addressed in the following review of just a few of the many important ceramics types that have been excavated during Jamestown Rediscovery’s excavations of James Fort. This review is intended to provide a glimpse into many years of future research that will cast new light on the early American ceramic assemblages that have generally received little attention by decorative arts scholars. As discoveries continue to be made at the site of America’s first permanent English settlement, our understanding of the cosmopolitan nature of ceramics trade and usage will be further refined in the next decade of exciting archaeological research.

Chinese Porcelain

The most obvious aspect of Dutch artist Christoffel van den Berghe’s painting is, as the title Bouquet of Flowers in Glass suggests, the beautiful central floral arrangement (fig. 5). But a closer look will reveal such exotica as seashells of the family Conidae, coming from the western Pacific, and tiny porcelain wine cups from China. The date of the painting is 1617, just fifteen years after the establishment of the United East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie), generally referred to as “V.O.C.”

In 1613 the V.O.C. ship Witte Leeuw (White Lion) sank in Jamestown Bay, a South Atlantic inlet off of Africa’s west coast, during a battle with two Portuguese merchant vessels. The settlement there, on the tiny island of St. Helena, was called Jamestown, half a world away from the colony founded by Englishmen in the New World. The two Jamestowns are inextricably linked however, by diminutive Chinese porcelain cups like those depicted in the van den Berghe painting.

The Witte Leeuw had stopped at St. Helena to take on fresh supplies for the rest of her trip back to the Netherlands, with a cargo of spices, diamonds, and porcelains from the East. This respite proved disastrous when two Portuguese carracks laden with goods from India chose the same protective anchorage. In the era’s struggle for dominance in the Eastern trade, the Portuguese and Dutch customarily sank or seized each other’s ships. And there was no exception this time. An English eyewitness to the ensuing battle revealed that a cannon on the Witte Leeuw “broke over his Powder Roome...and the shippe blew up all to pieces.”[2]

The Witte Leeuw was excavated in 1976. Among the many artifacts recovered by archaeologists are over three hundred complete or nearly complete Chinese porcelain vessels, plus another one hundred fifty to two hundred pounds of porcelain fragments (fig. 6). According to the divers on the wreck, the recovery probably represents only a quarter of the total porcelain cargo carried by the ship. These findings are surprising since the ship’s loading list made no mention of porcelain. Possibly the vessels were the personal goods of the captain, officers, or passengers, but the sheer quantity of material, the multiple sets of forms, and the decoration suggest that it was a cargo paid for and ordered by the Dutch V.O.C.[3]

Part of the porcelain assemblage includes at least forty small, thinly potted wine cups. Some are plain, but most are neatly painted, in underglaze blue just above the foot ring, with a band of scrolls under a flame pattern. “The shape is typical Chinese and resembles the well-known winecup or, in Japan, the sake-cup.”[4] The wine cups are of the type known as fine porcelain, and until their recovery from the Witte Leeuw it was not known that this quality of porcelain had been exported at such an early date. Fine porcelain in the early seventeenth century was customarily considered Imperial ware, reserved for use by the Chinese elite. Since the Witte Leeuw discoveries, however, these same wine cups have been recognized elsewhere, including another Dutch shipwreck, the Banda (which sank at Mauritius in 1615), thereby substantiating their use as export ware.

The wine cups reached the Netherlands at least by 1617, as evidenced by the Dutch still-life painting of that date depicting two of these vessels. The latest context in which these cups have been found is the 1640s shipwreck of a Chinese merchantman, known as the “Hatcher wreck,” in the South China Sea. Predating any of these examples is the wine cup excavated from a circa 1610 context within James Fort (fig. 7).

More than a dozen of these fine wine cups have been found on seventeenth-century archaeological sites along the James River in Virginia. Because of the wide range of contexts (ca. 1610–1640) in which these vessels have been found, the cups do not appear to have been part of a single shipment. In addition, the cups from the latter part of the period display different typological characteristics. The later vessels are thicker than the early examples and the decorative scroll-and-flame frieze is painted higher up on the body.[5]

The wine cup at James Fort was most assuredly brought by, or sent to, one of the gentlemen in the colony. A gentleman’s position in that society was assured as much by the material goods he possessed and the way he dressed as by any inherited title. As a rare and expensive object, the Chinese porcelain wine cup would be quite fitting as a status indicator for an upper-class individual.

The vessel may have been used to drink a strong alcoholic beverage such as the aqua vitae listed as part of each colonist’s provisions, or it may have been simply for ostentatious display. It was quite fashionable among European nobility and upper classes to assemble curiosity cabinets in the early seventeenth century. These displays consisted of objects, collected around the world, that were scientifically interesting, exotic, or precious. According to one art historian, “Naturalia—objets trouvés such as pearls and shells—were mixed quite happily with arteficialia, that is, precious man-made objects including coins, medals, paintings, sculptures, Nautilus goblets, astronomical gadgetry, etc.”[6] Porcelains, often mounted in silver or gold, were frequently part of these exhibits. In fact, a cabinet assembled between 1625 and 1631 for King Gustavus Adolphus II of Sweden contained three of the flame frieze wine cups.[7]

The Jamestown wine cup was most likely part of a Dutch shipment of goods from the East that was traded in London. The English were doing very little trade with China, even after the founding of the English East India Company in 1600. It was the Dutch East India Company that, in the late sixteenth century, wrested control of the East Indian trade from the Portuguese. Portugal had been the conduit for Chinese porcelains into Europe from the turn of the fifteenth century. The Dutch continued to hold the porcelain trade throughout the seventeenth century.

Portuguese Tin-Glazed Wares

By the late sixteenth century, the Portuguese potters had begun to produce a blue-and-white faience, reflecting their love of Chinese porcelain. The opaque white tin glaze made an appropriate background for the blue-painted Chinese motifs. The earliest known dated Portuguese faience is a bowl inscribed “1621.” The exterior of the bowl is decorated in panels of flower sprays and columns, in close imitation of Chinese Wan-Li models, like other vessels produced in the first quarter of the seventeenth century.[8]

By the second quarter of the seventeenth century, armorial motifs and other Western devices were introduced and the Chinese elements had become much more stylized. By the third quarter, manganese-colored outlines were introduced to the blue palette and large spiderlike devices were popular rim motifs (fig. 8).[9]

Portuguese chinoiserie was not very popular in England or the Netherlands; these countries were producing their own tin-glazed earthenware copies of Chinese porcelain. However, significant quantities of Portuguese faience have been recovered from archaeological sites in New England. This is believed to be the result of intense Anglo-Portuguese trade—which included fish and wood exports from New England—after Portugal’s independence from Spain in 1640.[10]

This pattern does not hold for the seventeenth-century Chesapeake Bay area of Maryland and Virginia. Very little Portuguese faience has been found on sites that would have been supplied by the English and the Dutch. The one exception occurs in the environs of Jamestown, where numerous vessels from contexts dating to the second and third quarters of the seventeenth century have been recovered (fig. 9, 10).

One large dish fragment in the Jamestown collection is painted with a duck on its interior base (fig. 11). The dish resembles the Chinese porcelain dishes painted with waterfowl that were also found on the Witte Leeuw shipwreck. The elements are somewhat debased, however, and represent a departure from strict adherence to the Chinese design.

Another series of at least six dishes, decorated with hastily executed striped borders radiating from a central floral motif (fig. 12), was found in the Jamestown area.[11] These dishes are from contexts dating to the second quarter of the seventeenth century. The same simple design, which may have been adapted to speed up production of export wares, has widespread distribution on New England sites dating from circa 1635 to 1675.[12]

These stylized designs do not appear to have a precedent in Chinese porcelain and may have evolved from Islamic origins. One author has suggested that their prevalence on North American sites “may have inspired the distinctive slip decoration of New England earthenwares in the late seventeenth century.”[13]

French Martincamp Ware

Well over four hundred neck and body pieces of odd-looking flasks known as “Martincamp” ware have been found in the Jamestown Rediscovery excavations (fig. 13). They also have been excavated from Virginia and Maryland sites dating to the first half of the seventeenth century. Martincamp flasks must have been produced solely for export, as they are rarely found in France where they were produced. But they are very common on sixteenth- and seventeenth-century sites in England along the eastern coast and the eastern half of the southern coast. In London they are found most frequently in seventeenth-century contexts with the highest concentration from circa 1650–1700. Surprisingly, no examples have been recognized in the Low Countries.[14]

Martincamp is a village in northern France situated between Dieppe and Beauvais. The flasks were called “Martincamp” because it was believed that this was the location of the kilns. Currently, ceramic historians believe that this attribution is too restrictive and that the ware may have been produced in a much wider area. Substantiating this belief is the fact that the Martincamp area has yielded neither large numbers of these flasks nor wasters.[15] (Wasters are defective vessels that are unusable, generally because of firing flaws, and are therefore discarded. They usually abound on kiln sites, providing the archaeologists with valuable information on the date and origin of wares.)

Three distinct body fabrics have been identified for Martincamp flasks. Type I flasks are earthenware with a date range of 1475–1550. Type II flasks are stoneware and are commonly found in the sixteenth century. Type III, which is rounder in form than the previous two types, has an earthenware fabric that usually is a low-fired orange color, but it can be fired to near-stoneware and appear reddish orange.[16] Only Type III flasks have been found at Jamestown.

Although other forms—rotund pots, chamber pots, and costrels—have been identified with the same fabrics in France, the only form found in Virginia is a thinly potted globular flask with a long tapering neck. The body of the flask is wheel thrown into a sphere. Once the sphere is leather-hard, the neck, which was thrown separately, is applied over a hole crudely punched in one end.

It is likely that Martincamp flasks were exported empty to serve as canteens for field workers and soldiers. This assumption has been derived from studying sixteenth- and seventeenth-century English trade records, which log in the values of cargo for tax purposes. The flasks, described in the port books as “earthen bottles,” are very inexpensive compared to the glass bottles that were exported with them from France. The low cost plus the lack of mention of any contents, which would have been subject to duty, suggest that the flasks were empty.[17]

The flasks would work quite well as water containers, for they were fired to a near-stoneware consistency. They could hold liquid, but since they were unglazed there would be some seepage, which would serve to keep the contents of the vessel cooler. In addition, the rounded shape of the vessel provided a form that could withstand more abuse without breaking. Since there are no handles, the only apparent problem as a field flask is transport. Customs documents provide an answer to this question as well.

Martincamp flasks are identifiable as the “bottles of earth covered with wicker” imported from French ports. Italian glass wine bottles having the same rounded shape were also encased in wicker at this time (fig. 14). The wicker covering on the glass bottles protected the wine from exposure to the ruinous effects of light. The same covering on the flasks would provide a way for attaching a strap so the vessel could be easily slung across a shoulder. In addition, a standing ring of wicker woven at the rounded base of the flask furnished the means for the flask to stand upright, thereby making it a costrel.[18]

North Italian Wares

Earthenware costrels from Italy are found occasionally on seventeenth-century Virginia sites (fig. 15). The form exhibits a long, narrow neck with either a rounded or baluster-shaped body on a turned foot (fig. 16). Unlike the Martincamp flask, it has integral attachment lugs—often in the shape of stylized lion heads—on each side of the body, through which a cord can be looped (fig. 17). A slip-decorated earthenware, costrels are made of the red-firing alluvial clays of northern Italy, particularly from the vicinity of Pisa. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the area along the Arno River between Pisa and Montelupo was the largest producer of exported Italian pottery. The Arno empties into the Ligurian Sea allowing easy distribution of the wares through the Mediterranean to northwest Europe and even to the Americas.[19]

These costrels are referred to as “North Italian marbled slipware,” since two or more colors of slip or liquid clay are swirled together on the surface of the vessel to create a marbled appearance. The colors can be a mix of just white and red or include a polychrome palette of orange, brown, and green.

North Italian marbled slipware was also produced in the form of dishes and bowls, with the latter comprising the most common export. A section of a very unusual bowl was recovered from an area within James Fort in a a circa 1625 context (fig. 18). The very wide vessel is decorated entirely with a dabbed, rather than swirled, white-and-red slip. Copper oxide in the lead glaze gives it an additional green mottled and streaked appearance.

Also made in Pisa, but less common than the marbled wares, are slipware dishes and bowls decorated with the sgraffito technique. Geometric and stylized zoomorphic or botanical motifs have been scratched through the white slip on the interiors of the vessels, creating a striking contrast between the red body and the yellow-appearing lead glaze (fig. 19, 20).

There is another ware type that was commonly lumped with seventeenth-century “Pisanware” even though it was made in Montelupo, another city on the Arno River. Unlike the red-firing alluvial clays of Pisa, Montelupo had fine buff fabrics that were suitable for tin glazing. In the sixteenth century, Montelupo faiences dominated the market and were widely distributed throughout Europe. By the seventeenth century the center of production for faience, also known as delftware, had shifted to France and the Netherlands.

Montelupo vessels are found infrequently on Virginia sites. When they are, they most often take the form of dishes and tazze—pedestaled shallow bowls or vases—painted in a polychrome palette of broad brushstrokes (fig. 21, 22). The design on the tazze is similar to the orange fruit with large oak leaves on the dish illustrated in figure 23. The most common motif on dishes of the early seventeenth century is figurative, usually depicting a soldier against a landscape holding various weapons or flags (fig. 24). The backs of the dishes are painted with parallel manganese concentric rings, which distinguish them from copies made in France and the Netherlands.[20]

Also known are Montelupo dishes with commedia dell’arte iconography. The commedia was an improvisational theater that developed in sixteenth-century Tuscany, but rapidly spread through Europe. Popular into the eighteenth century, it incorporated mime, gymnastics, and both scripted and unscripted dialogue. The commedia dell’arte performances would take place on outdoor stages, where they were accessible to the common people, as well as in the traditional theatres. Each actor in the traveling troupe would play the same role from among several stock characters, and although the actor was following a largely improvised script of one of several standard scenarios, there would be immediate audience recognition of the character from the costume and mannerisms.

A commedia dell’arte Montelupo dish was excavated from a circa 1635 to 1645 site adjacent to Jamestown Island, believed to have been inhabited by indentured servants.[21] The dish is decorated with a masked, bearded man wearing a black beret and holding a black cape in one hand while wielding what appears to be a dagger in the other (fig. 25, 26). This masked figure is one of the comic servants, or Zanni, who were among the central characters around which most of the plot focused. “At the heart of early commedia dell’arte plots,” explains one scholar, “lies the interplay between the masked duo of the servant Zanni and his master, Magnifico.”[22]

There are many variants of the Zanni costume, some worn by actors who portrayed the comic servant under a personalized stage name (fig. 27). These differences have not been sufficiently documented to enable positive identification of this particular Zanni, although his costume is compatible with a circa 1630 date.[23]

Since the commedia dell’arte performances had reached England by the seventeenth century, it is almost certain that the owners of the dish in Virginia were aware of the identity and significance of the depicted character. Although a rare find in Virginia, the dish would not have been a high status object in England. Its rustic style of painting is very much in the folk tradition like the English slipwares that were produced primarily for the poor to “middling” classes. Even so, the dish was probably a one-of-a-kind vessel in the household of Virginia servants and intended for display rather than use.

While North Italian wares are found widely distributed in Britain, they do not occur in large quantities and are most heavily concentrated in London and coastal towns. Examination of trade records for these towns reveals a problem that can be encountered while attempting to define trading patterns based on the appearance of ceramics. The archival record shows little evidence of Italian shipping in English ports during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Just because the wares are present does not mean that there is direct contact with their country of origin.[24]

Pottery was often sold and resold as it was imported to and redistributed in foreign lands. Spain is believed to have been the intermediary between Italy and the Spanish colonial sites in the Americas, where North Italian slipware has been found in contexts dating to the first half of the seventeenth century. Spain is also thought to be responsible for the redistribution of the ware in the southern English port of Exeter during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.[25]

North Italian wares occur on Virginia sites dating to the second quarter of the seventeenth century, a context coinciding with intense Dutch trade in the English colonies. This transatlantic commerce is believed responsible for the presence of these Italian wares on Virginia sites.

Raeren Stoneware

Even a quick glance at the Floris van Schooten painting A Kitchen Scene informs the viewer that he is looking at a wealthy Dutch household (fig. 28). Not only is there an abundance of food, but the metal cookware and the row of pewter dishes behind three matching Chinese porcelain bowls show the family’s ability to invest in high-priced vessels for the preparation, storage, and consumption of food.

Hanging beneath the shelf of porcelain and pewter are two blue-and-gray stoneware jugs mounted with pewter lids. These highly decorated baluster jugs were made in Raeren, Germany (now Belgium), specifically for decanting into drinking vessels of glass or precious metal. Primarily utilitarian, the jugs’ intricate molded designs, derived from contemporary printed sources, propelled them into objects of conspicuous display. “Relief-decorated stoneware quickly became a medium of social competition among the emerging mercantile and artisanal classes of northern Europe.”[26]

Raeren potters molded many different designs on the central panel of baluster jugs, including biblical and mythological scenes, details from popular contemporary prints, and armorial and political imagery. The important social role of these stonewares in European society contributed to their use by potters and by consumers who commissioned their wares to convey religious and political allegiances. Furthermore, “with the political and religious upheavals of the period, vessels decorated with the arms and portraits of contemporary rulers or historical figures were popular among gentry and mercantile class alike, both groups eager to display their fealty and political sympathies, even within the home environment.”[27]

The two jugs in the van Schooten painting promote a political stance through a very popular motif known as the “Seven Electors.” The seven electors (Kurfursten) comprised the Electoral College of the Holy Roman Empire. As such, they selected the emperor to rule the Germanic dominion that encompassed most of central Europe and Italy. The pope was the spiritual head of the empire, ruled by German kings from 962 until 1806. While the position of emperor was elective, by the seventeenth century it was solidly in the hands of the Austrian Habsburgs, part of the Catholic dynasty that commanded Spain, Portugal, a large part of Italy, and the southern Netherlands. The electors, who were not all Catholic, were hereditary office holders of the empire and included the bishops of Trier, Cologne, and Mainz, the king of Bohemia, the count palatine of the Rhine, and the dukes of Saxony and Brandenburg.

Raeren potters produced Seven Electors jugs in the first ten years of the seventeenth century for export and domestic use. Judging by the examples that have been excavated or that have survived in European museum collections, it was the most prevalently depicted theme on Raeren-molded baluster jugs. The design advertises political allegiance to the Habsburg-ruled Holy Roman Empire at a time of abounding political-religious conflicts in Europe. Catholic and Protestant rivalries were rife even among the German nation-states of the empire. Indeed, one of the electors, the count palatine of the Rhine, was a Calvinist who in 1609 encouraged the Protestant German states to form the Protestant Union. In response, the Catholic German states formed the Catholic League, supported by Spain, thus paving the way to the Thirty Years’ War.[28]

The Netherlands comprised a particular area of turmoil as Spain attempted to prevail over the Dutch territories. As one scholar has noted, Raeren’s proximity to these military struggles explains many of the designs employed by the potters working there.[29] Today, the village of Raeren lies in Belgium about one kilometer from the German border, but during the peak of its stoneware potting industry, four hundred to five hundred years ago, Raeren was a part of Germany located on the border of the regions collectively known as the “Spanish Netherlands.” As the Raeren potters attempted to appeal to as large a market as possible, they produced equal numbers of wares bearing the coat of arms or symbols of Spain or of the Habsburg family as they did those representing anti-Habsburg factions.[30]

The base section of a Raeren Seven Electors jug was recovered from a ditch within James Fort (fig. 30). Only a tiny fragment remains of the mid-girth frieze that, if complete, would have consisted of the arcaded busts of the seven electors, each behind a shield bearing his hereditary coat of arms (fig. 31). The jug fragment has a rampant lion holding an orb, which is the coat of arms of the count palatine of the Rhine. The palatine had its capital at Heidelberg and included strategically important land on both sides of the Rhine River between the Main and Neckar Rivers. The count palatine from 1583 to 1610, when the stoneware jug would have been made, was Frederick IV the Upright. Frederick IV practiced Calvinism and it was he who, in 1609, instigated formation of the Protestant Union.

If the Seven Electors jug was designed to advertise political loyalty with the Spanish-Habsburg dominion, what was it doing at Jamestown? The answer can, perhaps, be found in the policies of King James. A confirmed pacifist, one of James’s first acts as king was negotiating the end of the Anglo-Spanish war with the controversial 1604 Treaty of London. One historian states that peace with Spain was driven by James’s “desire for a dynastic union with Habsburg Spain as a mode of entry into the highest circle of European power and prestige.”[31] His apparent Spanish sympathies emboldened Hispanophiles in the Jacobean Court, such as the Earl of Northampton, to become more vocal in advancing Spanish and Catholic interests. Anti-Spanish groups, promoting an aggressive Protestant foreign policy, countered these actions. James had need for both and attempted to accommodate all factions by trying to forge alliances to strengthen his position. For instance, at the same time that his daughter married Protestant Elector Palatine Frederick V, he was arranging for the union of his son with the Catholic Infanta of Spain.

In short, English foreign policy at the time of Jamestown’s settlement was driven by the king’s alignments with the royal houses of Europe amidst political and religious dissension. So, the English fortified themselves at Jamestown with a wary eye cast in Spain’s direction; at the same time, Spain kept track of every move of the Virginia venture through spies and counterintelligence. The Seven Electors jug would not be out of place in such an environment. It was probably owned by a gentleman and was used or displayed to advertise his status in society.

The jug was one of the symbols of a Jacobean gentleman who moved in courtly or upper-class circles and affiliated himself with the strength and prestige of the Habsburgs no matter what their religious leanings. One such gentleman was Edward-Maria Wingfield, first president of the council in Virginia. In his own words Wingfield sums up the conflicting views of the upper class in response to charges that he had colluded with Spain to the detriment of the colony:

I confesse I haue alwayes admyred any noble vertue & prowesse, as well in the Spanniards (as in other nations); but naturally I haue alwayes distrusted and disliked their neighborhoode.[32]

Frechen Stoneware

Another stoneware vessel recovered from within James Fort also contains iconography that is reflective of pro-Catholic sentiments. It is a brown salt-glazed jug or bottle from Frechen, a village to the west of Cologne, Germany (fig. 32). Frechen stonewares dominated the English market from the mid-sixteenth century to the late seventeenth century, when the large-scale production of glass bottles and the development of English stoneware finally replaced them.

The jugs were primarily used for storage and serving beverages, a purpose for which they were ideally suited. The durable, non-porous stoneware body resulted in a vessel that could be easily cleansed of any odiferous substances and could contain liquids safely even under abusive circumstances. These stoneware jugs are often illustrated in Dutch tavern scenes sitting on the floor as decanting vessels while the drinker consumes beer or wine from a glass (fig. 33).

These bottles are known as “Bartmann” or “bearded man” for the bewhiskered face that adorns the neck (fig. 34). Bartmann jugs are also identified in the literature as Bellarmines, a term popularly believed to be a satiric reference to the much-despised Cardinal Robert Bellarmino (1542–1621). In 1606 Bellarmino, who, historically, has been described as “a zealous opponent of Protestantism in the Low Countries and northern Germany,”[33] publicly rebuked King James I for his treatment of English Catholics. While the English and Dutch may have made the association between the bulbous, grimacing jug and the Catholic prelate during the tempestuous religious climate of the early seventeenth century, it is unlikely that the form originated as a caricature: the first Bartmänner were produced around 1550 when Bellarmino was only eight years old.

The Bartmann jug, excavated from a circa 1607–1610 context within the palisaded walls of James Fort, exhibits parts of what would have been three ovoid medallions applied to its belly. Medallions on Bartmänner are often armorial, reflecting the coat of arms of appuent patrons, European cities and royal houses, ecclesiastical offices, or even the potter’s own Hausmarke or symbol.

The medallion on the James Fort jug consists of a crowned shield that has been divided into four quarters (fig. 35). In heraldic terms, the first and third quarters each exhibit a single lion passant, which means that he is walking with his right paw raised. The second and fourth quarters each have two lions passant. In the first quarter, which is the upper left-hand corner of the shield, there is a heraldic device known as a fess with a label on chief. This is the band across the upper third of the escutcheon that is carrying three stylized fleurs-de-lis. It is this label that identifies the medallion as Italian and, more specifically, as representing a member of the Tuscan Anjou party or Guelfs, who from medieval times were staunch supporters of the pope.[34] The Guelfs’ principal rivals in thirteenth-century Tuscany were the Ghibellines who backed the imperial power of the Holy Roman Emperor. These political factions had originated in Germany where they had comprised two feuding powerful families—the Wuelfs and the Hohenstaufen. The latter were the hereditary occupants of the imperial throne and once in Italy they, then known as the Ghibellines, had the support of the aristocracy. Artisans and lesser nobles supported the Guelf party. It was a political struggle that was to divide Tuscany until 1282 when, with the support of the pope (who resented the threat of imperial authority in Italy), the Guelfs finally prevailed. They continued to be fiercely loyal to the papacy into the seventeenth century.

The Guelf coat of arms has never before been recorded on German stoneware. Further, there is no documented trade of the ware in Italy, so the Bartmann jug from James Fort is extremely rare. An individual must have commissioned it, perhaps an Italian merchant, who had trade or other contacts with northwest Europe. But what was the jug doing at Jamestown? While potters produced armorial stoneware with an eye to where it would be marketed, finds of heraldic medallions should not be strictly used to identify locations of individuals. Marketing practices of the international stoneware trade resulted in random geographical distribution of armorial stoneware. Early-seventeenth-century Frechen jugs found in England were, for the most part, purchased in bulk by Dutch merchants who then shipped them to London where they were redistributed to English markets. The jugs changed hands many times as they were bought and resold, thus resulting in widespread dispersal of motifs.[35]

It may never be determined why this rare coat of arms with medieval connotations, showing Italian connections with the Rhineland and deference to papal authority, ended up at Jamestown. Was it the result of random distribution to a consumer oblivious to the jug’s symbolism or was it a purposeful statement by one of the colonists with papist leanings?

This question, as well as many others posed by the ceramic assemblages from the Jamestown Rediscovery excavations, is opening up new areas of historical consideration that have not been posed by the written record. Ceramic research at Jamestown will continue for years to come as discoveries are made—on both sides of the Atlantic. Every bit a primary source, the same as a letter or account written four hundred years ago, each vessel has a story to tell if we only learn to decipher the codes.

This article is adapted from Beverly Straube, Jamestown Rediscovery V (Richmond, Va.: Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, 1999).

Hakluytus Posthumus, or Purchas his Pilgrims, vol. 1 (London: n.p., 1925), as cited in The Ceramic Load of the Witte Leeuw, edited by C. L. van der Pijl-Ketel (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 1982), p. 19.

Ibid., p. 25.

Ibid., p. 143.

Julia B.Curtis, “Chinese Ceramics and the Dutch Connection in Early Seventeenth Century Virginia,” Vereninging van Vrienden der Aziatische Kunst Amsterdam (1985): I:6.

Norbert Schneider, Still Life (Cologne: Benedict Taschen, 1994), p. 158.

Van der Pijl-Ketel, Ceramic Load, pp. 28–29.

Joào Pedro Monteiro, Oriental Influence on 17th Century Portuguese Ceramics (Lisbon: Museu Nacional do Azulejo, 1994).

Stephen R. Pendry, “Portuguese Tin-glazed Earthenware in Seventeenth-Century New England: A Preliminary Study,” Historical Archaeology 33, no. 4 (1999): 64.

Ibid., p. 64.

Two were excavated from Martin’s Hundred (Ivor Noël Hume, Martin’s Hundred [New York: A Delta Book, 1982], p. 100) and four were found at the George Sandys site (Seth Mallios, At the Edge of the Precipice: Frontier Ventures, Jamestown’s Hinterland, and the Archaeology of 44jc802 [Richmond, Va.: Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, 2000]).

Pendry, “Portuguese Tin-glazed Earthenware,” p. 73.

Ibid., p. 73.

French researchers attribute these vessels to Noron, south of Bayeux in Lower Normandy, even though scientific analysis of the fabric has been inconclusive (Louise Décarie, Le grès français de Place-Royale [Québec: Government of Québec, 1999], pp. 17–18).

Pierre Ickowicz, “Martincamp Ware: A Problem of Attribution,” Medieval Ceramics (1993): 58.

John G. Hurst, David S. Neal, and H. J. E. van Beuningen, “Pottery Produced and Traded in North-West Europe, 1350–1650,” Rotterdam Papers VI (Rotterdam: Museum Boymans–van Beuningen, 1986), pp. 103–104.

John Allan, “Some Post-Medieval Documentary Evidence for the Trade in Ceramics,” in Ceramics and Trade, edited by Peter Davey and Richard Hodges (Sheffield: University of Sheffield, 1983), p. 42.

John Allan, Medieval and Post-Medieval Finds From Exeter, 1971–1980 (Exeter, Eng.: Exeter City Council and the University of Exeter, 1984), p. 113; Dennis Haselgrove, “Imported Pottery in the ‘Book of Rates’: English Customs: Categories in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries,” in Everyday and Exotic Pottery from Europe, Studies in Honour of John G. Hurst, edited by David Gaimster and Mark Redknap (Exeter, Eng.: Short Run Press, 1992), p. 327.

Hurst, Neal, and van Beuningen, “Pottery Produced and Traded in North-West Europe,” p. 30.

Ibid., p. 14.

Seth Mallios, Archaeological Excavations at 44jc568, The Reverend Richard Buck Site (Richmond, Va.: Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, 1999).

M. A. Katritsky, “Harlequin in Renaissance Pictures,” Renaissance Studies 11, no. 4 (1997): 381.

Dr. M. A. Katritsky, personal communication with author, 2000.

David Crossley, Post-Medieval Archaeology in Britain (New York: Leicester University Press, 1990), p. 256.

Kathleen Deagan, Artifacts of the Spanish Colonies of Florida and the Caribbean 1500–1800, vol. 1: Ceramics, Glassware, and Beads (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1987), p. 47; and Allan, “Some Post-Medieval Documentary Evidence,” p. 44.

David Gaimster, German Stoneware 1200–1900 (London: British Museum Press, 1997), p. 143.

Ibid., p. 153.

Gisela Reineking von Bock, Steinzeug (Cologne: Kunstegewerbemuseum, 1986), p. 273.

Gaimster, German Stoneware, p. 224.

Ibid., p. 224.

John Reeve, “Britain and the World Under the Stuarts, 1603–1689,” The Oxford Illustrated History of Tudor and Stuart Britain, edited by John Morrill (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), p. 416.

Edward-Maria Wingfield, “Discourse,” 1608, Lambeth Palace Library, MS 250, folios 382–96, cited in Phillip L. Barbour, The Jamestown Voyages Under the First Charter 1606–1609, vol. 1 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press for the Hakluyt Society, 1969), p. 229.

Gaimster, German Stoneware, p. 209.

John Hurst, personal communication with author, 1997.

Gaimster, German Stoneware, p. 82.