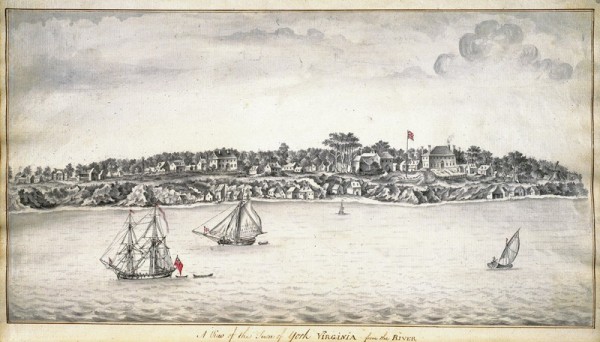

View of the Town of York Virginia from the River, 1754–1756. Colored drawing from Logbook #406 Voyage of HMS Success and HMS Norwich to Nova Scotia and Virginia. (Courtesy, The Mariner’s Museum.) Despite its industrial character, the William Rogers pottery was situated just one block from Yorktown’s Main Street and within eyesight of the town’s grandest residences.

Earthenware and stoneware “wasters” recovered from the William Rogers site in Yorktown, Virginia, ca. 1720–1745. (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park, Yorktown Collection.)

View of the archaeological excavations of the main workshop of the William Rogers pottery building complex, facing north. (Photo, Norman F. Barka.)

An oblique view photograph of the large kiln at the William Rogers pottery. These are the best preserved remains of an eighteenth-century stoneware kiln in America. (Photo, Norman F. Barka.)

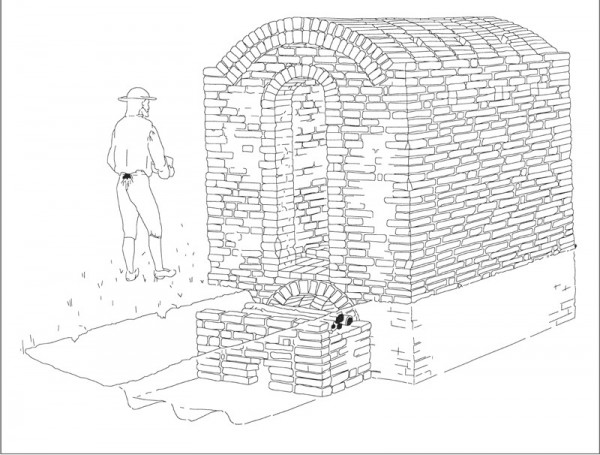

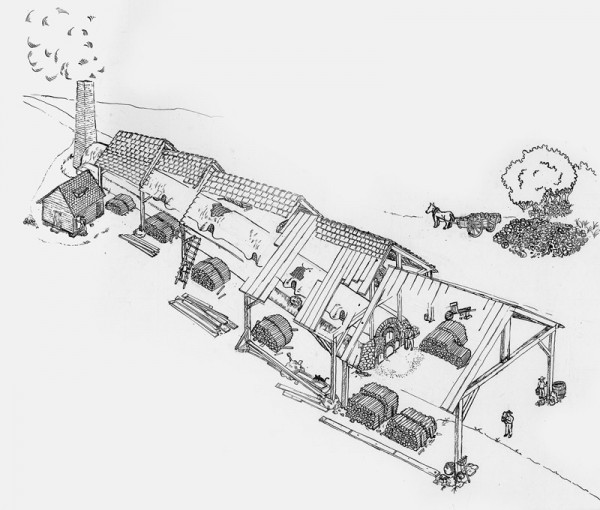

An artist’s reconstruction of the large kiln at the William Rogers pottery. (Drawing, Toni Gregg.).

View of the smaller of two kilns excavated at the William Rogers pottery. (Photo, Norman F. Barka.) The kiln is 5'6" high.

An artist’s reconstruction of the small kiln at the William Rogers pottery. (Drawing, Toni Gregg.)

Milk pans, William Rogers pottery, Yorktown, Virginia, 1720–1745. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 14". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park, Yorktown Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Mugs, William Rogers pottery, Yorktown, Virginia, 1720–1745. Salt‑glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park, Yorktown Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

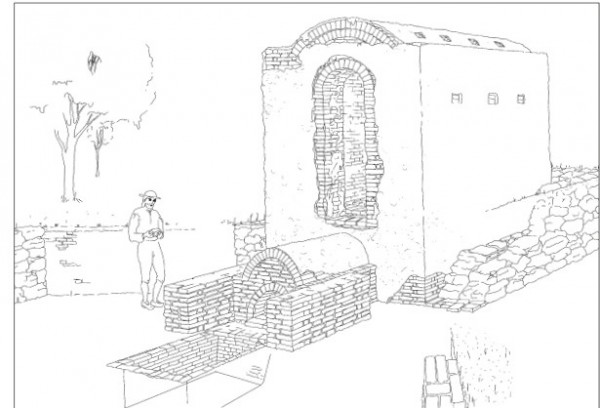

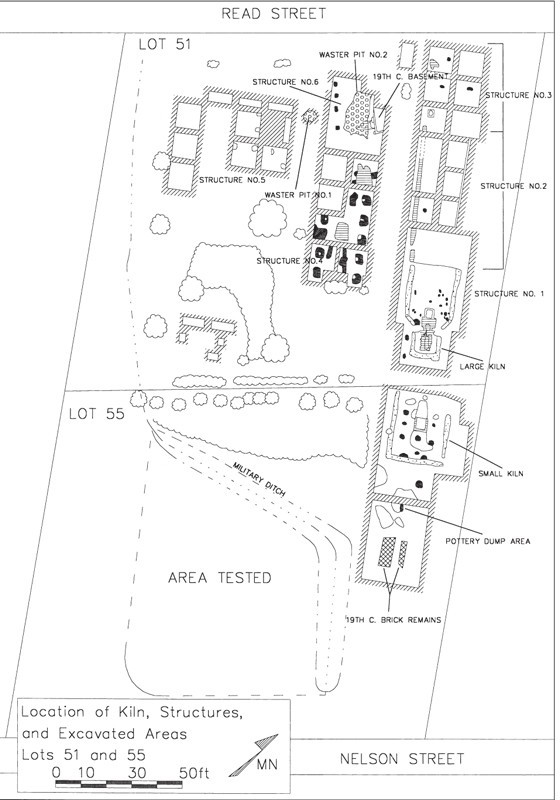

A plan drawing of the excavations detailing the locations of the kilns and related structures and features of the William Rogers pottery.

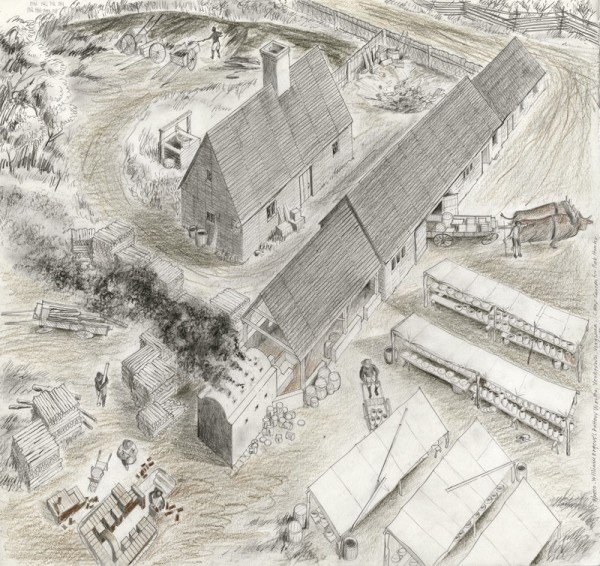

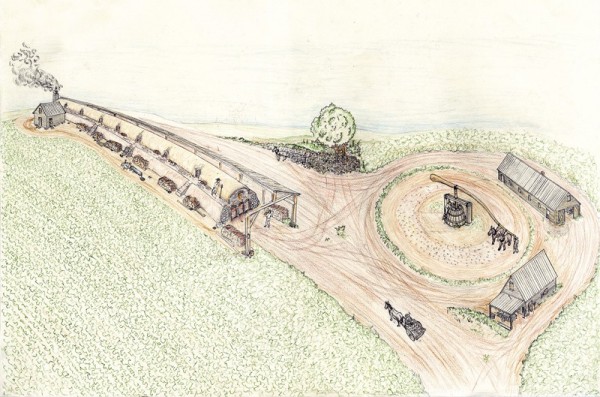

Artist’s reconstruction of the William Rogers pottery (ca. 1720–1745) in Yorktown, Virginia. (Drawing, Cary Carson.)

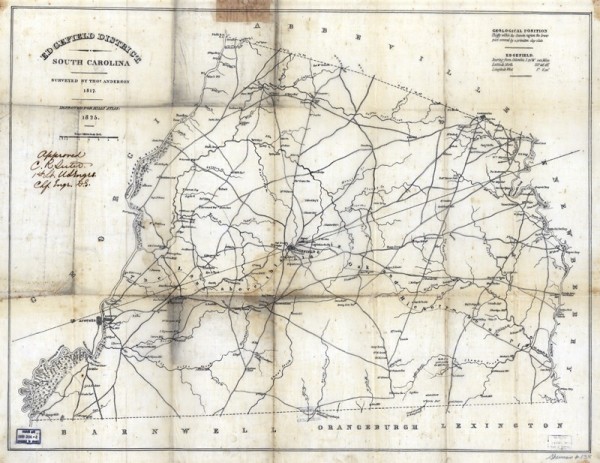

Mills Atlas of South Carolina, ca. 1825. These tracings, by the U.S. Army, are ca. 1860.

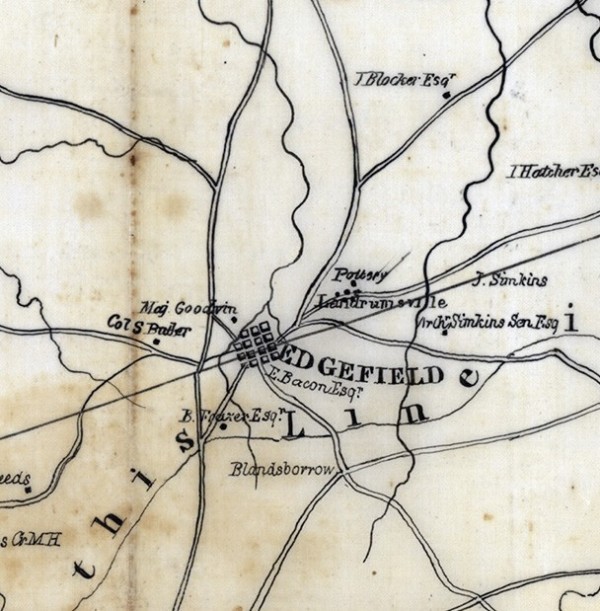

Detail of the map illustrated in fig. 12 showing the Edgefield community and the Landrum pottery to the northeast.

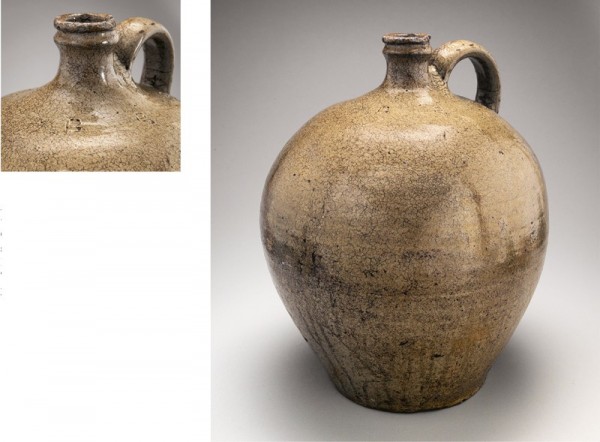

Bottle, Abner Landrum, Edgefield County, South Carolina, dated 1820. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 8". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) This small bottle is incised “July 20th 1820 / A. Landrum.” It is one of the earliest known pieces of dated Edgefield stoneware, and the only known example signed by Abner Landrum.

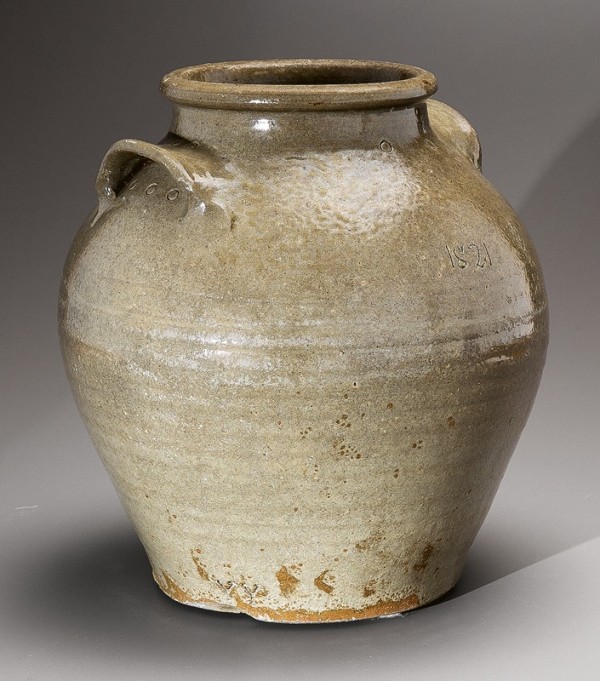

Storage jar, attributed to Pottersville, Edgefield, South Carolina, dated 1821. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) One of the earliest dated production vessels, this well-formed two-gallon storage jar is inscribed “1821” and further embellished with a series of circular punctates.

Storage jar, attributed to Pottersville, Edgefield, South Carolina, dated 1822. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) Another early dated example, this two-gallon storage jar is inscribed “July the 30th 1822.” In addition, it is stamped with seven “B”-like marks.

Storage jar, attributed to Pottersville, Edgefield, South Carolina, ca. 1820–1822. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) The jug has four stamped “B”-like marks, identical to those on the jar illustrated in fig. 16.

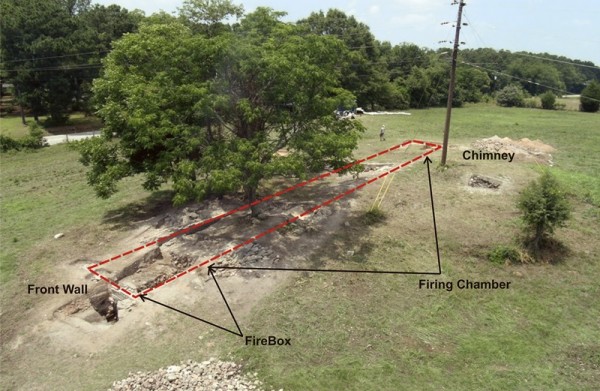

Excavated remains of the Pottersville kiln in 2011, with key architectural features indicated. (Photo, George Calfas.)

Conjectural reconstructive drawing of the Pottersville kiln. (Drawing, Oliver Mueller-Heubach.)

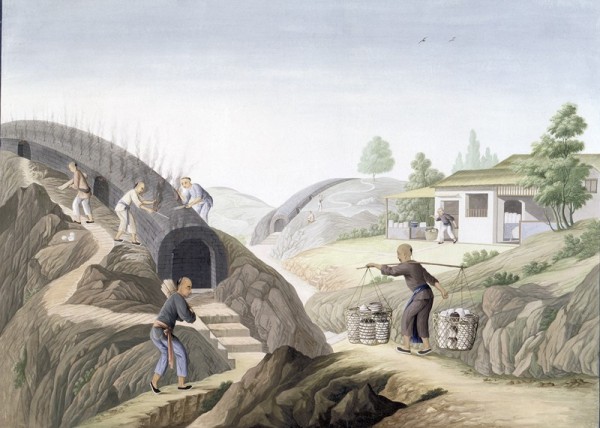

Painting of a dragon kiln, China, ca. 1825. Gouache on paper. 20 7/8 x 15 3/8". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex; Museum purchase with funds donated anonymously, 1983, E81592.14.)

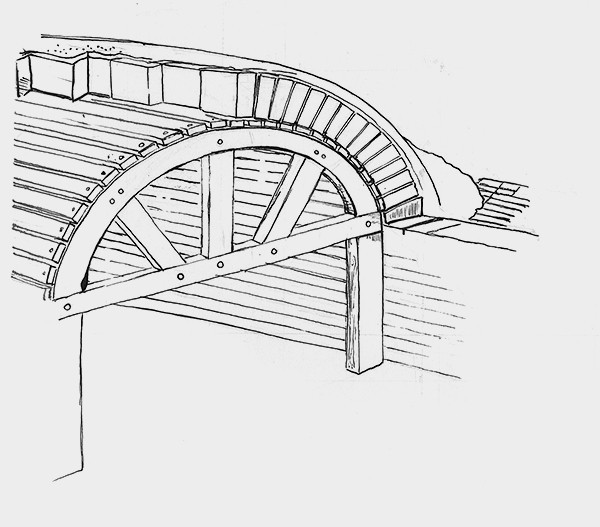

A conjectural drawing suggesting how the kiln’s catenary arch might have been constructed using a wooden form that was subsequently removed after the bricks were laid. (Drawing, Oliver Mueller-Heubach.)

Storage jar, Lewis Miles pottery, Edgefield, South Carolina, dated 1840. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 15 1/2". (Harvard Art Museums; photo, Robert Hunter.) This six-gallon jar is inscribed “January 27th 1840” and “Mr Miles Dave” with punctuates and slashes. It is a highly important example of David Drake’s work, the earliest known example signed with his name, “Dave.”

Conjectural reconstructive drawing of the Pottersville kiln. (Drawing, Oliver Mueller-Heubach.)

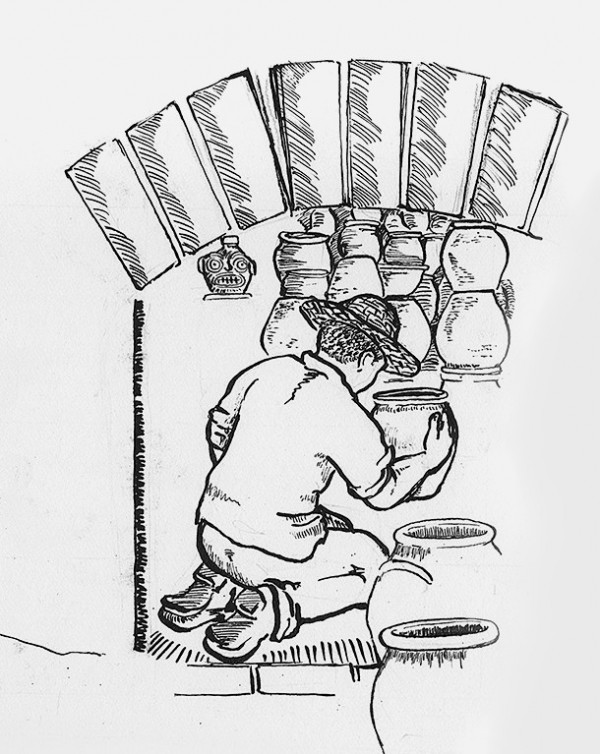

Conjectural drawing of workshop activities at Pottersville showing the throwing of large jars. (Drawing, Oliver Mueller-Heubach.) Activities were organized in an assembly-line fashion with individuals assigned specific tasks such as preparation of clay balls for throwing and handle making.

Loading the kiln. (Drawing, Oliver Mueller-Heubach.) The loading of the kiln was one of the most critical aspects of the entire manufacturing progress.

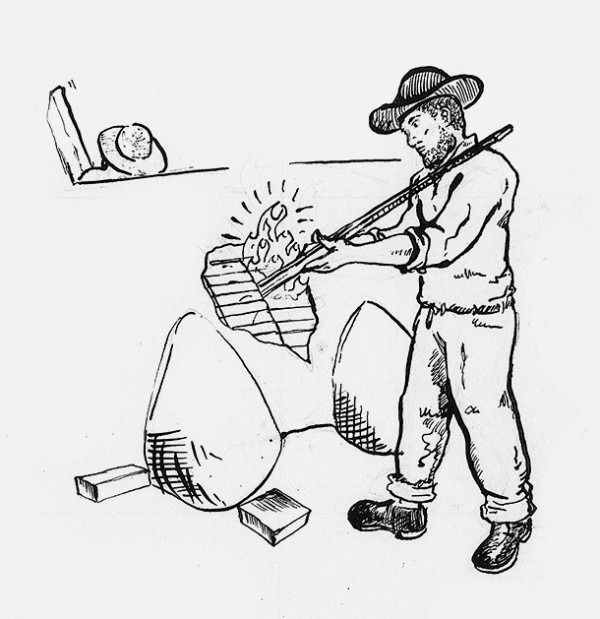

Conjectural drawing of workers stoking the side ports of the kiln. (Drawing, Oliver Mueller-Heubach.) The fuel used for these side ports was generally smaller than the larger planks used in the main firebox.

For those who are faced with photographs of often indiscernible archaeological features or cryptic line schematics, a reconstructive drawing trumps all other forms of data. What follows is a brief presentation on two of America’s most important kiln sites, introducing large-scale conjectural drawings of the kilns and surrounding environs showing workshops, clay processing, packing, storage, and other work areas. The drawings are based on extensive archaeological work, and it is hoped that they will breathe life into the extensive body of historical and archaeological documentation for both of these sites.

The first site is that of the workshops and kilns of William Rogers of Yorktown, Virginia, who operated from about 1720 until his death about 1740.[1] In addition to his extensive earthenware products, Rogers is celebrated as the first American potter to fully realize salt-glazed stoneware technology in the colonies.

The second site is that of Pottersville in Edgefield, South Carolina, where the amazingly large-scale kiln of Abner Landrum appears to have been modeled after the ancient, massive dragon kilns used in China. Landrum also produced stoneware, but with an alkaline glaze, and was certainly the first in the American South to do so on a large scale. The use of alkaline glazes became de rigueur for the countless folk potteries operating in Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and even Texas through much of the nineteenth century.

Although conjectural, the drawings presented here help to clarify the highly organized division of labor and sophisticated manufacturing and firing processes at these sites. They also offer a starting place from which to evaluate other production sites as they are studied in the future. For further background about the history and archaeological investigations of the William Rogers factory, readers are referred to Norman F. Barka, “Archaeology of a Colonial Pottery Factory: The Kilns of Ceramics of the ‘Poor Potter’ of Yorktown,” and Martha W. McCartney and Edward Ayres, “Yorktown’s ‘Poor Potter’: A Man Wise Beyond Discretion,” both published in the 2004 volume of Ceramics in America. For the history and archaeological investigations of the Pottersville kiln, readers can refer to George Calfas’s Ph.D. dissertation, “Nineteenth Century Stoneware Manufacturing at Pottersville, South Carolina: The Discovery of a Dragon Kiln and the Reinterpretation of a Southern Pottery Tradition,” University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013, and his article “A Dragon Kiln in the Americas: European-American Innovation and African-American Industry,” published in the Journal of African Diaspora Archaeology and Heritage in 2017.

William Rogers of Yorktown, Virginia

Although Yorktown is best known for its pivotal role in the American War of Independence in 1781, a much quieter revolution was already taking place there by 1720. At that time, entrepreneur William Rogers established America’s earliest and most complex pottery factory, producing both earthenware and salt-glazed stoneware to supply the needs of the local colonists who typically depended on English manufactures for their ceramics.[2] As the British Crown generally discouraged colonial industry, Rogers’s pottery is among the first American attempts to gain economic independence from reliance on English-made household goods. Several decades of archaeological and historical research have shed light on Rogers’s operation, yet many questions remain unanswered. One thing is clear: his workers generated products rivaling those of the best English factories. These wares were used not only by virtually all of the inhabitants of the Tidewater region of Virginia between 1720 and 1745, they also were shipped to Maryland, North Carolina, New England, and ports in the Caribbean.

Yorktown was well suited for the success of Rogers’s business enterprise (fig. 1). Located on the banks of the York River, Yorktown was close to the Virginia Colony’s capital at nearby Williamsburg, and in the first half of the eighteenth century it functioned as an important port and center of trade. Commerce was the primary activity, with planters bringing tobacco and other crops to be shipped out while receiving the latest, most fashionable goods arriving from England.

Little is known about William Rogers’s background. He may have lived in Southwark, England (near London), before coming to Virginia about 1710. Documents indicate that he was involved in trade, sending goods from England to ports in Pennsylvania and Virginia. Among his many endeavors, by 1711 Rogers had a successful business as a brewer selling ale to Yorktown’s taverns.[3] In May 1711 he bought lots 51 and 55 in Yorktown and by 1720, as part of his growing commercial interests, had begun a pottery.[4]

Rogers himself was not a potter but rather a multifaceted businessman. He is consistently referred to in historical records as a “merchant” and “gentleman.” His ceramic wares complemented his own brewing trade for he could supply his tavern keepers with appropriate earthenware and stoneware vessels. He also sold his wares to a wide range of wholesale and retail customers throughout Tidewater Virginia. William Rogers operated his pottery contrary to British laws and regulations, but apparently he had the tacit approval of Virginia’s Royal Governor, who was responsible for protecting the trade interests of the Crown. In a series of annual reports to the Lords of the Board of Trade beginning in 1731, Governor William Gooch referred to a “poor potter” in Yorktown.[5] Presumably he used the term “poor” to minimize the perception of any potential threat to the livelihood of English potters and merchants, because research has made it clear that Rogers was anything but poor. The scope of his factory was nearly at an industrial scale, and certainly accounted for a sizable portion of the household and tavern utilitarian wares for the regional population. Governor Gooch’s collusion in this venture reflects his desire to promote the economic success of the Virginia colony while at the same time satisfying the concerns of the British government.

The important story of William Rogers might have gone untold were it not for several fortuitous archaeological discoveries augmented by historical research and analysis. The existence of an eighteenth-century pottery in Yorktown remained forgotten until 1956, when Colonial Williamsburg’s resident archaeologist Ivor Noël Hume identified, in the artifact collection of the National Park Service, ceramic fragments and pieces of kiln furniture associated with local pottery making.[6] Fragments of locally made earthenware and stoneware were also discovered in the archaeological excavations at Colonial Williamsburg, confirming the existence of a pottery working in the Tidewater area (fig. 2).

Historical research revealed the identity of William Rogers as the “poor potter” of Yorktown, but it was not until the discovery in 1966 of a large waster pit filled with failed examples of Rogers’s pottery on Lot 51 that the actual location of the factory came to light. In 1970 a large kiln was discovered beneath the floor of a modern garage and subsequently excavated; two years later, Norman F. Barka of the College of William and Mary began a multiyear project uncovering and recording much of what is known of the physical layout of the pottery on Lots 51 and 55.[7]

The major finds on the property include two pottery kilns, a large workshop complex, two waster pits, other related features, and hundreds of thousands of earthenware and stoneware fragments (fig. 3). The remains of the kilns are among the best preserved early-eighteenth-century examples in the world (figs. 4-7). Similar kilns excavated in large cities in England, London among them, have not survived the passage of time so well.[8] Because the small village of Yorktown has stayed largely undeveloped, the archaeological footprint of the kilns and other features on the site survived relatively intact. The below-ground remains of the kilns include the fireboxes, the flues and arches, and stoking pits where the wood fuel was added and ashes were removed. The capacity of the largest kiln found on the property has been estimated at approximately 310 cubic feet.

The production of lead-glazed earthenware at the factory required biscuit and glaze firings. More than twenty lead-glazed earthenware forms have been identified, including storage jars, bowls, bottles, mugs, pipkins, porringers, chamber pots, and sauce pans.[9] Bird bottles used as martin houses were a distinctive product of this pottery. Molded, lead-glazed stove tiles are another unusual item made there. One of the most common earthenware forms recorded was the milk pan (fig. 8). This essential device was used to separate the cream from milk in order to make butter and cheese. Fragments of these milk pans have been found in numerous Tidewater domestic archaeological sites dating to 1730–1740.

Rogers’s production of salt-glazed stoneware is the first recorded instance of this technology being used in America. The most common stoneware product was the tavern mug (fig. 9). These mugs are nearly identical to the English goods of the period, indicating skilled potters threw them. The potters were also aware that those delicate forms required individual saggers for protection during firing. Other common stoneware forms produced at Rogers’s factory were brown-dipped storage jars and bottles, all of which have direct parallels in English prototypes. Sizes seem to have ranged from half a gallon to five gallons. Other unusual but useful stoneware forms were butter churns, chamber pots, and, most notably, fashionable teapots and coffeepots. These beautifully made teawares were the equal of the finest London brown stoneware examples of this period.

While the preserved remains of the two kilns, one of which is visible today, continue to generate a great deal of excitement among the archaeological community and the public, the majority of the potting operation took place in the workshop building. Less attention has been paid to the archaeological evidence for the three separate but connected structures that made up the workshop complex, which was approximately 17 feet wide and more than 170 feet long.

The sheer size of Rogers’s factory suggests that many individuals were at work there, each having specific duties similar to English ceramic factories of the period. Most of the names and backgrounds of the potters who worked for William Rogers are not known. The high quality and diversity of the wares produced there suggest that one or more master potters were directing the production, but where they came from and how they were trained remains one of the site’s biggest mysteries. Research by historian Martha McCartney suggests that Rogers’s workforce included slaves and indentured servants, several of whom were listed by name in his will.[10] Were the slaves Tony, Harry, Jack, and Phillip responsible for some of the pots that have been excavated on this site? If so, they might be among the first African-Americans trained specifically in the pottery craft. It was also common practice to acquire skilled labor from the British penal system; convict servants occasionally caused Rogers problems, however, as their names appear frequently in the Virginia court records for various misdeeds. Although William Rogers’s skilled and experienced potters remain anonymous, they left their marks on each and every pot they made.

Activities included the preparation of raw clay, the throwing and trimming of vessels, and the making and applying of handles. In addition, the ware had to be dried and decorated, glazes prepared, the kiln had to be loaded, and wood for fuel gathered. Once the kilns were fired and subsequently unloaded, the finished wares were sorted and packed for transport. It is likely that many hands were involved in the production of a single pot.

As part of the continuing research effort around the excavated materials from the site and after many years of speculation, a drawing was commissioned to better visualize the totality of the site (fig. 10). In transforming the site plans and other excavated and historical information, Cary Carson, the now-retired Senior Vice President of Research for Colonial Williamsburg, combined his considerable knowledge of vernacular architecture and his artistic skills to produce a rendering of what the Rogers factory may have looked like in its heyday (fig. 11).[11] The workshops, kilns, waster pits, and related work areas are seen in elevation rather than as a flat site plan. It is hoped that the visual rendering of the features uncovered at the site will help foster an appreciation for the industrial scale of this important factory, and help underscore its importance as America’s first large-scale pottery manufactory.

Abner Landrum’s Pottersville Kiln, Edgefield, South Carolina

The pioneering industrial community of Pottersville lay just east of the town of Edgefield, South Carolina (figs. 12, 13). That upcountry seat emerged at the turn of the nineteenth century as the legal and political hub of a rapidly developing cotton economy. The Edgefield district produced ten governors and gave rise to several manufactories, none so unusual as the revolutionary alkaline stoneware pottery begun by Abner Landrum at Pottersville.

An unlikely ceramic entrepreneur, Augusta physician Abner Landrum’s interests in science and technology combined with his medical training to draw him to the stoneware industry. A visit to his mentor’s native Philadelphia area introduced the young Landrum to the Quaker potter John Vickers, who sparked in him progressive ideas both scientific and moral.[12] Landrum’s medical background may have rendered him particularly appreciative of lead-free “alkaline” glazes, recipes for which had been tried in Philadelphia at least once.[13] Such glazes had the benefit of being food safe, regardless of the acidity of the contents, and were wholly locally-sourced, not relying on the salt or expensive cobalt employed by potters in the mid-Atlantic and Northeast. Before Landrum, American stoneware potters drew much of their knowledge from English and German salt-glaze traditions, the former characterized by brown-dipped wares, such as William Rogers’s, and the latter being variously festooned with cobalt on gray. Salt, and especially cobalt, were significant investments, being generally absent from the vicinity of good clay deposits. Composed of fine sand, slaked wood ash or lime, and pure kaolin, alkaline glaze offered an economical and beautifully varied alternative to traditional European wares. Edgefield held rich kaolin beds, abundant timberland, and an ever-growing captive labor force that ultimately served as the primary consumers of these utilitarian wares.

Commercial cotton production and industrial potting would mature in tandem in South Carolina, with stoneware vessels becoming a conduit of the foodstuffs requisite to slave culture. Cheap, durable containers became indispensable as cotton production boomed and the enslaved population eclipsed the free. Prodigious quantities of pork and other salted and pickled preserves had to be transported and stored. An estimated 10,000 six-gallon vessels were needed to support just the enslaved population of 1820.[14] Add to this breakage and typical losses with each firing, and the potential scale of stoneware production in the Edgefield district is clear. Edgefield’s central location and abundant resources allowed it to serve low-country South Carolina and Georgia via road networks and a pioneering railroad line. Good stoneware clay nurtured potteries as clay fields fed the cotton.

Using Edgefield’s bounty of natural resources, Landrum introduced the district to the industrial production of necessary, durable, and healthful goods. Between 1809 and 1810, two separate properties were being developed as kiln sites: the hill near what became Abner’s Pottersville, and the land by the home of his brother John, a minister. Abner began his enterprise with a three-year, $2,000 grant and admirable scientific rigor, reporting to his creditors in 1815 that he had produced fine specimens of porcelain, glass, stoneware, and other items yet bemoaning the cost of skilled workmen.[15] By 1817, Landrum had devoted himself to stoneware at both kiln sites (fig. 14). While the vaunted porcelain experiment failed—a single bisque cup is tantalizing proof that it was, indeed, attempted—Landrum’s kilns became ground zero for a remarkable stoneware tradition that would spread across the American South (figs. 15-17).[16] The early industry was characterized by strong Landrum family connections: brothers Abner, Amos, and John; Abner’s nephews Harvey Drake, Reuben Drake, and B. F. Landrum; and Abner’s son-in-law Lewis Miles operated at least four early pottery manufactories in the district. Today, they represent the archaeological sites of Pottersville (Site 38ED11), Rev. John Landrum (38AK497), B. F. Landrum (38AK496), and Lewis Miles’s Stony Bluff (38AK854).[17]

While long known to area historians, the Pottersville site received formal attention when archaeologists from the University of Illinois confirmed the location of the kiln and set about a systematic survey of the site that included close-interval shovel testing informed by pedestrian survey and aerial LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) images. The LiDAR maps not only brought the earthen hump of the buried kiln into relief, they also suggested that the bulk of Pottersville’s structures might survive undisturbed under a modern road.[18]

The University of Illinois team, led by George Calfas, opened twenty-four excavation units at the kiln site over the course of the 2011 field season (fig. 18). From the initial confirmation of the foundation to individual components such as the ware chamber, the firebox, and the chimney, the work of Calfas and his team is used here to produce a conjectural reconstruction of the kiln incorporating numerous archaeological details (fig. 19). Those details include the number of courses of stone surrounding the fireboxes, the bonds used in building the walls and lining them, and the maintenance of the ware floor. The massive scale of the kiln is evident in its basic element, the made-on-site firebrick measuring 1 ft. x 1 ft. x 4 in. Calfas estimates that 7,500 of these oversized refractory bricks went into the construction.[19]

Earlier American salt-glaze stoneware traditions were associated with a variety of relatively compact rectangular and oval kiln designs, developed for efficiency in close urban quarters. Provided with Southern rural settings, these had developed into the groundhog kiln, which grew somewhat in length as it “burrowed” into earthen banks, optimizing insulation and draught. These kilns reached a maximum recorded length of 35 feet.[20] The kiln the team at Pottersville uncovered, however, dwarfed the anticipated groundhog type, revealing itself to be a totally unexpected 12 ft. x 105 ft. Realizing it was unlike any American kiln of the period, Calfas and others made a connection between Pottersville and the ancient tradition of Asian so-called dragon kilns (fig. 20). Already a thousand years old when it attained its standard form during China’s Song dynasty, ca. a.d. 960–1279, the dragon kiln was the workhorse of porcelain and stoneware mass production in Asia. The “dragon” conjured therein was a massive 30–80-meter undulating form of brick, rising up a slope as much as 20 degrees. Prodigious waster piles issued from its “mouth” and “feet”: this fiery dragon gorged on vessels and spat out the “bones.”

Archaeological remains at the other Edgefield kilns of the Rev. John Landrum, Lewis Miles’s Stony Bluff, and B. F. Landrum demonstrate the increasing uniformity of this new tradition. As archaeologists found in 2011, the brick had all but vanished from the John Landrum site, leaving broken stretches of rubble cut by an access road and jutting off onto private property.[21] A white firebrick clay floor represented the ware chamber, similar to other area kilns. The extant rubble reached at least 18 meters, or 59 feet, thus making it at least a third longer than known groundhog kilns.

Excavations at the B. F. Landrum site in 2013 and 2014 uncovered telltale parallel lines of rubble representing kiln walls separated by the shallow dip of an ashy interior floor.[22] The intermittent remains of wall rubble and relatively sterile former kiln interior stretched at least 91 feet. Charleston Museum researchers working in the 1930s noted that the kiln at the 1867 Miles Mills pottery would be even longer than the B. F. Landrum structure.[23]

Like B. F. Landrum’s kiln, Lewis Miles’s circa 1848 Stony Bluff kiln would use the natural slope of about eight degrees to climb a full 105 feet, taking advantage of the natural draft provided by elevation and exposed hillside. It appears to have benefited from experimentation at Pottersville, and was built to those specifications while incorporating the narrower, nine-foot interior the Pottersville structure adopted in its rebuilding. The roofs were vaulted, though only Pottersville has produced the special “skew blocks” that were cut to initiate the arch and have been used to calculate the minimum span (fig. 21).[24]

The greatest point of conjecture in rendering the Pottersville kiln is its timber roof. While no archaeological posthole features were found to indicate a wooden superstructure, both Asian dragon and American groundhog kilns generally employ coverings. They protect the potters and firewood, and save the long brick vault from erosion and thermal shock due to weather. The many nails excavated from the kiln rubble might relate to this superstructure. Nails also occurred in most of the ware chamber’s seven floors, perhaps reflecting the stokers’ use of scrap lumber as a supplemental fuel source.

The immediate source for the Pottersville or any other of the large Edgefield kiln designs remains a mystery. Oft-copied and wonderfully detailed scenes of Chinese porcelain production at Jingdezhen were almost certainly one inspiration, although they provide only external views. It is doubtful whether early written descriptions generated by the likes of the Jesuit François Xavier d’Entrecolles in China could provide sufficient detail to re-create a working design.[25] Fireboxes, flues, slope, height, and draft would all be crucial considerations. There was little room for error, for to lose the contents of such a massive kiln to a failed firing would mean months of man-hours wasted.

The men, women, and children who labored making stoneware in Pottersville were white and black, native and immigrant. The initial labor force was begun with white men, but later free blacks and slaves,[26] who, Abner Landrum acknowledged, were “as ingenious, and considering their opportunities, as intelligent, as the mass of our laboring white population.”[27] By 1832 as many as 150 people were living and working within sight of the kiln. The presence of family units ensured that Pottersville held a strong social aspect, evidenced by large numbers of refined tablewares found in the erstwhile production zones, unlike the John Landrum site.[28] Carl Steen and Corbett Toussaint prepared an extensive database of workers linked to potting in the Edgefield district.[29] Thanks to their research, the full names of several dozen of those workers have been identified, although, as with many enslaved communities, most are known only by given names. Unfortunately, very few of the Pottersville workers could be identified. We know that Dave, Daniel, and Buster (Brister) worked as turners at Pottersville in 1820, together with one or more white potters. Abram and Tom are also associated with the operation. Many more individuals can be tied to the other antebellum kilns, such as those of John Landrum, B. F. Landrum, Amos Landrum-Colin Rhodes, and Lewis Miles’s Stony Bluff.

The labor was arduous but varied, with each worker performing multiple tasks in the process. Two slaves could, in two to four days, cut ten tons of wood, and in an additional day mine nine tons of clay, the quantities needed to support a single firing. Calfas estimates that each potter might turn 25 six-gallon vessels in a day.[30] Each firing could hold thousands of vessels. Estimates of two to three potential firings per month, though unlikely, would yield a maximum of 24 to 36 firings per year.[31]

Edgefield’s most recognizable product was the simple storage jar, sometimes of prodigious size, 20 gallons or more. While the form is now inextricably linked with the story of Dave the Potter and his elusive inscriptions and verse, those appeared only after the pottery changed hands to Drake in 1828 (fig. 22). Another icon of Edgefield stoneware, the culturally laden “face jug,” is also absent in the early period and would appear only in the 1840s and 1850s when a handful of vessels, invested with greater meaning than their syrup, liquor, and vinegar-toting brethren, were modified. By far, the most typical vessels at Pottersville were utilitarian jugs and jars, along with lesser numbers of bowls and churns as well as rarities like cups and plates.[32]

By 1826 the complex with its associated village of “Landrumsville” had grown to include seventeen worker residences, out lots, workshops, and kilns.[33] As on any large plantation, a variety of supporting trades from coopering to blacksmithing were practiced within sight of the Landrum kiln. Wagons were repaired, harnesses mended, gardens tended, and tools wrought and maintained. Unfortunately, to date we have no ground truthing of the village structures beyond the suggestive LiDAR images.

The landscape through which the clay flowed on its way to become finished stoneware has really just begun to be interpreted (fig. 23). Archaeological work in 2013 focused on revealing Pottersville’s working landscape as it spread out along and below the kiln.[34] Jamie Arjona and Tatiana Niculescu report “at least six other associated rectangular structures . . . indicating a vast and complex production center.”[35] Clustered around the nurturing pug mill, the workshop buildings sat on footings of clay, their bricks laid in clay mortar.[36]

The flow of work at Pottersville began in the north, where raw clay was mined. Once dug, the clay was picked over for large debris and carted south by oxen, horses, or mules, to the workyard, where it was fed into a massive pug mill. There, blades studding a revolving shaft chopped and mixed the clay over and over, finally extruding it from the base whence workers carried it away to stockpile. The clay was aged and wedged, compressed and further worked by hand, removing bubbles and rendering it uniform before being shaped into balls of set weight and size that the turners could slam down on the wheels.

The Landrum turning-shop equipment included at least three potter’s wheels; a ten-inch gear found at the site could represent the base of a wheel head. While some vessels were turned all at once, larger pots were thrown in halves, set aside to stiffen and be joined, top to bottom. Once cut from the wheel for the last time, other, perhaps smaller hands set about adding handles, gallon markings, and decorative treatments. Pots sat in anticipation of a further stage, in damp cool for some, in bright sun for others. All the while, potters and family members busily gathered, soaked, and sifted ash, ground silica, mixed glaze, rolled and pulled batches of handles and engaged in myriad other tasks (fig. 24). When the pots became able to take glaze without folding or cracking, they were dipped one after another in vats of thick, gray glaze, then carried off for final drying, perhaps to a dedicated structure. One such was suggested by pier features alongside the chimney at the far end of the kiln; it may have used heat from the firing to speed the drying process of successive loads of pots, a feature found in European traditions.

As firing day approached, all hands would have been busy clearing debris from the kiln, patching cracks, building up a floor, and finally loading the ware chamber with pots through doors at each end (fig. 25). Though taller inside than a groundhog kiln, loading an Edgefield kiln was still a cramped task, and no doubt women and children were involved here as elsewhere. With everything in and the doors and openings bricked and plastered shut with clay, the fire would be lit and stokers would slowly feed the three mouths of the firebox.

Even those not directly involved in the process could gaze northward from Pottersville and gauge the progress by sight and perhaps even smell. There, atop the hill, wind carried the sweet scent of pine pitch, hot brick, and steaming clay as the kiln gradually warmed. As suggested by Asian dragon kilns in use today, the fire would bake out the wares as it climbed the hill with each section sealed tight when it attained temperature. The flanks of the mammoth kiln were buttressed and insulated by continuous earthen ramps paved with stone. Stokers likely paced the ramps, ready to feed small amounts of fuel into stoking ports glowing red, orange, yellow, finally white-hot (fig. 26). Asian examples and the sheer length of the kiln indicate some side-stoking would have been necessary. As at historic and modern kiln firings, the long burn was a community event, and the fires provided entertainment and nighttime warmth, an impromptu cooking hearth, and a setting for games, music, and stories. The masses of wood heaped along the kiln diminished, first gradually, then precipitously as peak temperature was achieved. The kiln would then be sealed up and allowed slowly to cool.

When the ware chamber settled to a safe temperature, the openings were unbricked, and a bucket brigade assembled to pass wares out of the depth of the kiln. Once checked for defects and abraded of adhesions and burrs, some were loaded directly into wagons bound for markets far and near, others sold on site or set aside for later pickup. The routine carried on, firing after firing, year after year.

At Pottersville, the kiln fell cold sometime in the 1840s, its fireboxes still sealed. The design carried on another twenty years while skilled potters and seasoned laborers spread from Edgefield throughout the region. Even at the B. F. Landrum, Stony Bluff, and the Miles Mill sites, however, the dragon design was abandoned after the 1860s, having overtaxed nearby fuel sources and having lost the plantation bulk economy on which it had prospered. A dozen potteries operated in the district between the 1810s and 1910.[37] In its last half century in Edgefield, industrial potting was recast in the mold of the English-style factories of New Jersey, abandoning traditional stoneware for tablewares. Alkaline glaze, however, would go far beyond Edgefield. Edgefield craftsmen would carry alkaline formulas, together with proven templates for kilns, tools, structures, even whole landscapes, across the South, from North Carolina to Texas. Regional Southern alkaline traditions and their revivals are alive and well today thanks to Pottersville.

The drawing of the William Rogers kiln and accompanying discussion were previously published in Robert Hunter, “William Rogers of Yorktown, Virginia, 1720–1739: America’s First Stoneware Potter,” in This Blessed Plot, This Earth: English Pottery Studies in Honour of Jonathan Horne, edited by Amanda Dunsmore (London: Paul Holberton, 2011), pp. 142–49.

Robert Hunter, Kurt Russ, and Marshall Goodman, “Stoneware of Eastern Virginia,” Antiques 167, no. 4 (April 2005): 126–33.

Martha W. McCartney and Edward Ayres, “Yorktown’s ‘Poor Potter’: A Man Wise Beyond Discretion,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. 48–59.

The beginning date for the pottery is based on a lead-glazed earthenware “dedication” porringer excavated at the base of the larger of the two kilns on the property. It is inscribed with the initials “A.C.” and the date “1720”; the identity of “A.C.” is unknown.

British Public Records Office, London, Colonial Office Papers 5/1323, fols. 62–66, 82, 93–94.

C. Malcolm Watkins and Ivor Noël Hume, The “Poor Potter” of Yorktown (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1967).

Norman F. Barka, Edward Ayres, and Christine Sheridan, The “Poor Potter of Yorktown”: A Study of a Colonial Factory, Colonial National Historical Park, Virginia, 3 vols. (Denver: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1984).

Chris Green, John Dwight’s Fulham Pottery: Excavations 1971–79 (London: English Heritage, 1999).

These wares are described and illustrated in Norman F. Barka, “Archaeology of a Colonial Pottery Factory: The Kilns and Ceramics of the ‘Poor Potter’ of Yorktown,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. 15–47.

McCartney and Ayres, “Yorktown’s ‘Poor Potter,’” p. 52.

Cary Carson, Norman F. Barka, William M. Kelso, Garry Wheeler Stone, and Dell Upton, “Impermanent Architecture in the Southern American Colonies,” Winterthur Portfolio 16 (Autumn 1981): 135–96.

Carl Steen, “Summertime in the Old Edgefield District,” South Carolina Antiquities 43 (2011): 74–75.

Jamie M. Arjona, “Jug Factories and Fictions: A Mixed Methods Analysis of African-American Stoneware Traditions in Antebellum South Carolina,” Journal of African Diaspora Archaeology and Heritage 6, no. 3 (2017): 174–95: “Dr. Abner Landrum may have designed this alkaline formula after tinkering with viable alternatives to lead-based glazes. By the 1810s, Landrum had channeled his bookish fascination with ceramic chemistry into an industrial-scale enterprise at Pottersville” (ibid., p. 180).

Orville Vernon Burton, In My Father’s House Are Many Mansions: Family and Community in Edgefield, South Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1985); John Michael Vlach, “International Encounters at the Crossroads of Clay: European, Asian, and African Influences on Edgefield Pottery,” in Crossroads of Clay: The Southern Alkaline-Glazed Stoneware Tradition, edited by Catherine W. Horne (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press and McKissick Museum, 1990), pp. 17–39.

Zev A. Cossin, “The Social Landscape of Potteries: Refined Earthenwares at Pottersville, South Carolina,” Journal of African Diaspora Archaeology and Heritage 6, no. 3 (2017): 225–42, esp. p. 233; George Calfas, “Nineteenth Century Stoneware Manufacturing at Pottersville, South Carolina: The Discovery of a Dragon Kiln and the Reinterpretation of a Southern Pottery Tradition,” Ph.D. diss., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013, p. 68.

Leonard Todd, Carolina Clay: The Life and Legend of the Slave Potter Dave (New York: W. W. Norton, 2008), p. 30.

Calfas, “Nineteenth Century Stoneware Manufacturing at Pottersville”; Carl Steen, Archaeology at the Reverend John Landrum Pottery Site, 38AK497: 1987–2014: A Preliminary Report (Columbia, S.C.: Diachronic Research Foundation, 2016); Carl Steen, Archaeology at the B. F. Landrum Stoneware Kiln Site, 38AK496 (Columbia, S.C.: Diachronic Research Foundation, 2016).

George Calfas, “A Dragon Kiln in the Americas: European-American Innovation and African-American Industry,” Journal of African Diaspora Archaeology and Heritage 6, no. 2 (2017): 133–54, esp. p. 139.

Ibid., p. 140.

Locally, at the Trapp-Chandler Site 38GN169, Kirksey’s Crossroads, as well as John Landrum associate James Kirbee’s kiln in Texas. Steen, Archaeology at the Reverend John Landrum Pottery Site, 38AK497, p. 46.

Ibid.

Steen, Archaeology at the B.F. Landrum Stoneware Kiln Site, 38AK496.

Ibid., pp. 88, 94.

Calfas, “Nineteenth Century Stoneware Manufacturing at Pottersville,” pp. 180, 201.

See https://gotheborg.com/letters/entrecolles.pdf.

Arjona, “Jug Factories and Fictions.”

Christopher C. Fennell, “Innovation, Industry, and African-American Heritage in Edgefield, South Carolina,” Journal of African Diaspora Archaeology and Heritage 6, no. 2 (2017): 72.

Zev A. Cossin, “The Social Landscape of Potteries,” Journal of African Diaspora Archaeology and Heritage 6, no. 3 (2017): 230, 233; Calfas, “A Dragon Kiln in the Americas.” For earlier work at the John Landrum site, see Brooke E. Kenline, “Entrepreneurs and Industrial Slavery in the Antebellum South,” master’s thesis, Ohio State University, 2012; and Steen, Archaeology at the Reverend John Landrum Pottery Site, 38AK497.

Carl Steen and Corbett Toussaint, “Who Were the Potters in the Old Edgefield District?,” in Journal of African Diaspora Archaeology and Heritage 6, no. 2 (2017): 78–109.

Calfas, “Nineteenth Century Stoneware Manufacturing at Pottersville,” p. 269.

Ibid., pp. 270–71.

Fennell, “Innovation, Industry, and African-American Heritage in Edgefield, South Carolina,” pp. 55–77; Jamie Arjona and Tatiana Niculescu, “Turning Clay into Craft: Field Notes from the 2013 Excavations at Pottersville, SC,” South Carolina Antiquities 46 (2014): 77–80, 184.

Robert Mills, Statistics of South Carolina (New York: Hurlbut and Lloyd, 1826), pp. 523–24.

Arjona and Niculescu, “Turning Clay into Craft.”

Ibid.

Arjona, “Jug Factories and Fictions,” p. 180.

Steen and Toussaint, “Who Were the Potters in the Old Edgefield District?”