Plate, probably Staffordshire, ca. 1790. China glaze. D. 10". (All objects private collection, unless otherwise noted; all photography Gavin Ashworth, unless otherwise noted.) China glaze is most often associated with underglaze chinoiserie decoration. Unfortunately, these early China glaze wares were rarely marked by their manufacturers. One painted design appears to have been standardized by the English potters which Ivor Noël Hume and others have called the “Chinese house pattern.” Innumerable variants of this design exist. The common thread between them is the formulaic layout of the pattern’s primary features: trees, fence, house or pagoda, fence, and more trees. The foreground almost always consists of shimmering water with assorted rocks and plants. Although the specific origin of the pattern is unknown, it appears to have been adapted from chinoiserie patterns painted on English porcelains of the 1750s and 1760s rather than directly from Chinese prototypes.

Plate, probably Staffordshire, 1775–1790. Creamware. D. 9 3/4". An example of the Chinese house pattern on a creamware plate with unusual molded rim. Cobalt decoration on the cream-colored ware does not successfully mimic the look of Chinese or English blue-and-white porcelain.

Bowl, Worcester, 1770–1780. Soft-paste porcelain. D. 11". This punch bowl is painted in a pattern that has been called “Rock Strata Island.” The Caughley porcelain factory made an identical version of this pattern.

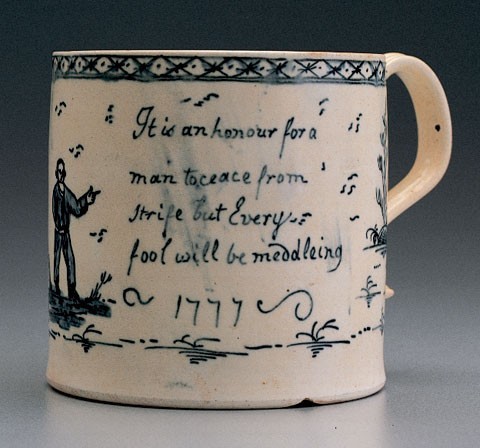

Mug, Staffordshire or Yorkshire, 1777. Creamware. H. 4". (Collection of Troy D. Chappell.) An early example of the Chinese house pattern on a creamware body.

Reverse of the mug illustrated in fig. 4. (Collection of Troy D. Chappell.) The painted inscription reads: “It is an honour for a / man to ceace from/ strife but Every / fool will be meddling/ 1777.” The date on this mug demonstrates that blue-painted chinoiserie patterns were being produced on earthenware before Josiah Wedgwood’s introduction of Pearl White in 1779.

Punch bowls. (Left): Leeds pottery, ca. 1780. China glaze. D. 10". (Right): Yorkshire or Staffordshire, 1777. Creamware. D. 8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) These bowls exemplify the close relationship between China glaze and the creamware bodies.

Interiors of the punch bowls illustrated in fig. 6. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) The decorated interiors of these bowls are reminiscent of inscribed delft punch bowls. The inscription on the left reads “May the / Evening Deversion [sic] / bear the / Mornings [sic] Reflection.” The interior of the bowl on the right has a coat of arms with “1777” and “I. N.”

Detail of the foot rings of the punch bowls illustrated in fig. 6. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) The pooling of cobalt in the foot ring is clearly evident in both examples.

Spill vase, Yorkshire or Staffordshire, ca. 1775. Creamware. H. 6 7/8".

Reverse view of the spill vase illustrated in fig. 9. This early example combines elements of rococo design with the odd juxtaposition of the Chinese house pattern on the reverse of this molded vase.

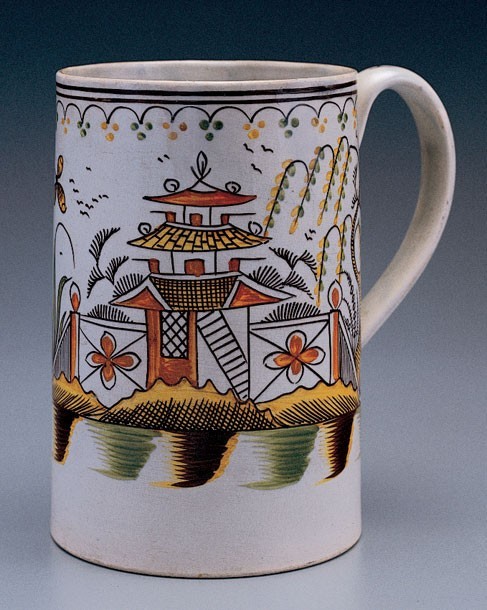

Mugs, Staffordshire or Yorkshire, 1775–1810. China glaze. H. 4 1/2" to 6". Mugs are among the most commonly recovered China glaze forms on American archaeological sites.

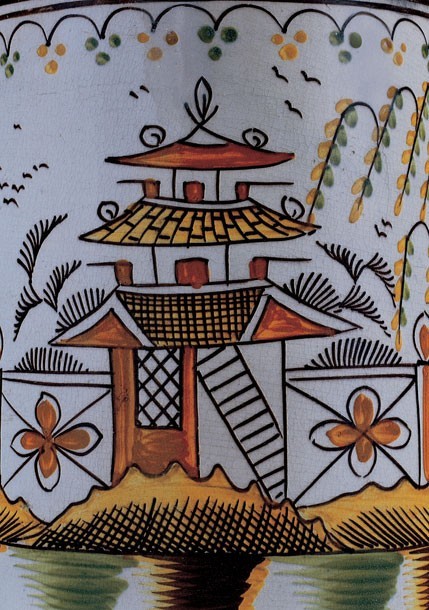

Mug, Staffordshire or Yorkshire, ca. 1790–1810. China glaze. H. 6 1/4". Polychrome-painted China glaze mugs are much less common than blue-painted ones. The introduction date for underglaze-painted colors has not been documented. One reason that polychrome pieces may be less common is that blue-painted patterns began twenty years before the polychrome-painted patterns were introduced.

Detail of the underglaze pattern on the mug illustrated in fig. 12.

Mug, Staffordshire or Yorkshire, 1790–1810. China glaze. H. 5 1/4". Another example of underglaze polychrome decoration used in combination with blue painting.

Coffee pots, Staffordshire or Yorkshire, 1780–1810. China glaze. H. 12 1/8" and 7 3/8". Coffee pots are much less common than teapots in all painted and printed wares. The example on the left is unusual in that it has traces of original gilding.

Teapots, Staffordshire or Yorkshire, 1775–1800. China glaze. H. 6" and 6 1/2". Egg-shaped teapots were common forms associated with the Chinese house pattern. The example on the left is unusual in having an overglaze enamel decoration.

Teapot and tea canister, Staffordshire or Yorkshire, 1790–1810. China glaze. H. of teapot: 5 3/8". An interesting use of the Chinese house pattern on a neoclassical form.

A group of tea wares, probably Staffordshire, 1775–1785. China glaze. H. of cream jug: 4 5/8". For a short period of time, some China glaze tea wares were decorated with overglaze enameling and gilding in imitation of the Imari porcelains. Although no records exist, these were undoubtedly more costly China glaze items.

Coffee cup and saucer, and tea bowl and saucer; Staffordshire or Yorkshire, 1775–1810. China glaze. H. of coffee cup: 3 1/4". Tea bowls and saucers appear frequently in the American archaeological record. They are far more common than China glaze plates and mugs. Most cups are handleless and in a Chinese tea bowl shape. Handled coffee cups are quite rare, however. We have not seen any marked or dated pieces of this form.

Cream jugs, Staffordshire or Yorkshire, 1775–1810. China glaze. H. 3 1/8" to 3 3/8". Cream jugs were made in a tremendous variety of shapes. Note the four different types of pouring lips. These shapes mimic the larger jug forms of the period.

Cream jugs. (Left): probably Staffordshire, ca. 1775. Creamware. H. 3 1/2". (Right): Staffordshire or Yorkshire, 1790–1820. China glaze. H. 3 1/4". The example on the left is enamel-decorated in a European-style house pattern. The jug on the right is decorated under the glaze in a debased chinoserie pattern.

Punch bowls. (Left): probably Staffordshire, ca. 1775. Creamware. D. 8 7/8". (Right): Staffordshire or Yorkshire, 1790–1810. China glaze. D. 6". The creamware punch bowl is enamel-decorated in a European-style house pattern. The pearlware bowl is decorated in polychrome colors under the glaze.

Punch bowls, Staffordshire or Yorkshire, 1775–1810. China glaze. D. 9 1/4" and 9 7/8". Punch bowl forms in a wide variety of sizes appear ubiquitously in American archaeological sites.

Various China glaze forms. Left to right: spill vase, mustard pot, two-handled cup, and spitting cup; Yorkshire or Staffordshire, 1775–1810. China glaze. H. of vase: 6 1/4". Almost every imaginable form appears to have been made and decorated in the Chinese house pattern between 1775 and 1820. Blue-printed patterns continued to be used on virtually every form produced by the English potting industry well into the nineteenth century.

Dish, Staffordshire or Yorkshire, 1775–1810. China glaze. D. 14 1/2". A large, shell-edged serving dish painted with a very elaborate Chinese house pattern.

Plates and dishes, Staffordshire or Yorkshire, 1775–1810. Creamware and China glaze. As suggested in this grouping, tremendous variations of the Chinese house pattern were used in conjunction with the shell-edged rim treatment on both creamware and pearlware dishes. This assemblage provides strong evidence that many potters produced these wares. They are almost never marked, generally have rococo blue shell-edged rims, and date from 1775 to 1800. The introduction of underglaze transfer printing in Staffordshire in 1784 may have reduced the market for Chinese house pattern painted wares. The occurrence of plates and other tableware painted with the Chinese house pattern is relatively rare in the American archaeological record. Conversely, large numbers of antique plates and dishes seem to survive in England. This dissimilarity, perhaps reflecting a difference in the market, warrants further investigation.

Plate, Staffordshire or Yorkshire, 1785–1810. China glaze. D. 93/4". A variant of the Chinese house pattern on a pearlware plate; the rim decoration simulates molded relief panels and reserves. This rim type suggests a date after 1785.

Plates, Staffordshire or Yorkshire, 1775–1810. Creamware and China glaze. These dinner plates, decorated with the Chinese house pattern, all have different molded or painted rim treatments. Some of these rim treatments are shared by undecorated creamware patterns.

Plate, impressed “IH” for Joshua Heath of Tunstall, Staffordshire, ca. 1790. China glaze. D. 8". A black-printed China glaze shell-edged plate copying a Chinese pattern. This pre-Willow pattern print is line engraved. The “IH” mark is one of the few seen on China glaze wares.

Dish, impressed “IH” for Joshua Heath of Tunstall, Staffordshire, ca. 1790. China glaze. L. 15 1/2". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation.) A blue-printed example of the same print illustrated in fig. 29.

Bowl, Ching-tê-chên, China, 1785–1820. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 4 3/8". Blue-painted Chinese bowl in what collectors call the “Canton” pattern or ware. The Canton pattern is one of the most simplified of the well-known Chinese porcelain export wares for the West. It is commonly dated as beginning around 1785 when Americans began trading with China. Given the simplicity of this pattern, one wonders if it is a copy of some of the China glaze wares being made in Staffordshire. Is it a Chinese copy of an English earthenware copy of English porcelain that was a copy of Chinese porcelain? How may times has the compass spun?

Dish, probably Staffordshire, ca. 1820. China glaze. L. 18 1/2". A debased version of the Chinese house pattern painted on a shell-edged dish of about 1820, possibly even as late as 1830. Note that the “house” and “fences” are missing elements of the design. This design is identical to the one on the small creamware jug illustrated in fig. 21.

Jug, possibly Lancastershire, 1821. China glaze. H. 9". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation.) The elaborate painting on this jug would suggest a much earlier date than the one inscribed on this presentation piece.

One of the most common earthenwares found on American archaeological sites dating from the 1780s until the 1830s has a bluish tint to its glaze. It is generally known by the term “pearlware,” a name adopted from Josiah Wedgwood’s Pearl White, which he introduced in 1779. The other Staffordshire potters, however, called this ware “China glaze” and appear to have begun producing it as early as 1775. This paper explores what led to the development of China glaze, and how its name disappeared from general usage until the mid-twentieth century.

The Quest for Chinese-Style Porcelain in England

Importation of Chinese porcelain into Europe provided a great catalyst for experimentation in the quest for the secret of making porcelain. That quest for the arcanum fathered a host of new wares and improvements in old ones. A variety of soft-paste porcelains was developed using fritted glass, soapstone, or calcined bone, in combination with white-firing clays and calcined flint. In addition to the soft-paste porcelains, the white-firing clays and calcined flint also became ingredients in whiter wares such as white salt-glazed stoneware, creamware, and stone china. The pursuit of the arcanum was spurred on by Johann Friedrich Böttger’s success in producing a Chinese-style porcelain in Meissen, Germany, in 1710.[1]

The solution to the mystery of porcelain became clearer when the Jesuit missionary Père D’Entrecolles provided detailed descriptions of the production process and the materials used by the Chinese. D’Entrecolles was a missionary to the Ching-tê-chên region of China. From there, he sent two long, detailed descriptions of the porcelain-making process, one in 1712 and the other in 1722. Du Halde incorporated this information into his history of China, published in English in 1725.[2] Knowledge of how the Chinese made porcelain and the key ingredients used gave a new sense of direction for the quest by English potters. By the middle of the eighteenth century English soft-paste porcelain works had been established in Bow, Chelsea, Liverpool, and Worcester to make imitations of this coveted ware.

It was not until the 1740s, when William Cookworthy, a Quaker apothecary interested in chemistry, found extensive deposits of kaolin clay and petuntse in Cornwall that an English hard-paste porcelain could be produced.[3] Ceramic historian Bernard Watney states that William Cookworthy “at first followed Père D’Entrecolles’s description meticulously, but he soon found that his formulae had to be amended” to make them work.[4] Cookworthy patented his hard-paste porcelain formula in 1768 and built a factory to produce the wares in Plymouth, Cornwall, that same year. In 1774 Richard Champion, one of Cookworthy’s partners, purchased his patent and moved the factory to Bristol. The production of a hard-paste porcelain had met with limited success and had absorbed a lot of capital. In an attempt to be sure that he would be able to recover his investment, Champion attempted to have the patent renewed by Parliament in 1775.[5]

Champion’s request for the renewal of Cookworthy’s patent was fought vigorously by Josiah Wedgwood on behalf of the Staffordshire potters. In his appeal for the renewal of the patent, Champion wrote about the great expense of producing the porcelain and described the difficulties they had to overcome. Champion stated:

There is one branch of the manufacture, the blue and white, upon which he has just entered, this branch is likely to be most generally useful of any: but the giving of a blue color under the glaze, on so hard a material as he uses, has been found full of difficulty. This object he has persued [sic] at great expense by means of a foreign artificer; and can now venture to assert that he shall bring that to perfection which has been found so difficult in Europe in native clay.[6]

Wedgwood argued that Cookworthy and Champion had already had time enough to take advantage of their patent. He further argued that to extend the patent would deprive others of the opportunity to experiment with these materials and would also deprive landowners of the value of kaolin and petuntse, or Growan stone, deposits that existed in abundance. It is interesting to note that Wedgwood’s Common Place Book for 1775 contains an account of the Chinese method of manufacturing porcelain.[7]

In May 1775 Parliament came up with a compromise that brought about major changes in the Staffordshire pottery industry. Champion’s patent to make porcelain out of the materials from Cornwall was renewed; however, the rights to use kaolin and Growan stone were open to all potters so long as they did not make porcelain.

Within days of the patent renewal, Josiah Wedgwood, John Turner, and Thomas Griffiths traveled to Cornwall, secured mining rights to kaolin and Growan stone, and set up a cooperative to ship these materials to Staffordshire for anyone to purchase and use.[8] After setting up the cooperative, Wedgwood tried to establish a potters’ organization to experiment with the new wares, but was unsuccessful.[9]

Cobalt, Blue Painters, Enamelers, and the Staffordshire Potters

Cookworthy and Champion’s problems in using cobalt blue under the glaze had been overcome by a number of potters producing soft paste well before the Cookworthy patent. Bernard Watney’s English Blue and White Porcelain of the Eighteenth Century illustrates many blue-painted patterns in a Chinese style on vessels from Bow, Liverpool, and Worcester dating to the 1750s. The success of these potteries in producing blue-painted wares a couple of decades before Champion’s patent renewal application suggests that Cookworthy and Champion’s problems were due to their lack of a pottery background. Champion sold his patent to a group of Staffordshire potters who set up the New Hall Pottery in 1781 to produce hard-paste porcelain; the potters do not seem to have had any problem producing blue-painted wares.[10] In August 1778 Wedgwood summed up Champion’s problems in a letter to his partner Thomas Bentley:

Poor Champion is quite demolished...he had neither the professional knowledge, sufficient capital, nor scarcely any real acquaintance with the material he was working on.[11]

In some ways, cobalt blue was as important an element in the quest for porcelain as kaolin and Growan stone. Use of cobalt for decorating pottery began with the Dutch delft potters who established factories in England in the sixteenth century. Until the mid-eighteenth century, cobalt use in England was mostly limited to delftware. By the 1750s, the use of cobalt by the emerging soft-paste porcelain industry was becoming common. Cobalt was also becoming more common on Staffordshire products such as scratch-blue salt-glazed stoneware.

Decorators for the nascent porcelain industry were probably recruited from the delftware industry, which had been suffering a loss of market share to white salt-glazed stoneware, as well as from the success of new porcelains. Lorna Weatherill’s dissertation provides estimates of the number of persons employed in the various types of potteries in England from 1740–1800. Table 1 clearly illustrates the takeoff of the porcelain and fine earthenware potteries in the last half of the eighteenth century and the rapid decline of the delftware industry.[12]

Table 1 Weatherill’s Estimates of the Number of Workers Employed in Various Branches of the English Pottery Industry, 1740–1800

| Year | Delft | Stoneware | Fine earthenware | China |

| 1740 | 665 | 633 | 165 | |

| 1745 | 600 | 588 | 280 | 65 |

| 1750 | 635 | 656 | 610 | 270 |

| 1755 | 620 | 565 | 855 | 365 |

| 1760 | 640 | 577 | 1,335 | 445 |

| 1765 | 495 | 375 | 1,960 | 450 |

| 1770 | 380 | 350 | 2,635 | 280 |

| 1775 | 290 | 330 | 3,375 | 290 |

| 1780 | 120 | 270 | 4,325 | 390 |

| 1785 | 55 | 325 | 5,560 | 365 |

| 1790 | 385 | 7,210 | 385 | |

| 1795 | 431 | 8,050 | 525 | |

| 1800 | 505 | 8,945 | 850 |

The delftware painters were blue painters as opposed to enamelers. Enamel painters, because they painted on top of a stable, fired glaze, were able to operate independently of the factory structure or as employees working outside the pottery factories. The fired blank wares from a porcelain factory could be safely transported elsewhere for enameling. In contrast, the delftware blue painters had to work within the potteries because they painted on a very friable, unfired glaze. After painting, the delftware had to be fired again in the high-temperature delft kilns.

The declining delftware industry could not provide the number of painters needed for the new porcelain industry. In a 1740 petition to Parliament, Nicholas Sprimont, a partner in the Chelsea porcelain works, asked for protection against losses caused by German porcelain smuggled into England. His justifications for protection cited the contribution their factory made to the economy. This included the establishment of a nursery of “thirty lads taken from the parishes and schools and bred to designing and painting,” thus providing the poor with careers.[13]

Another indication of the shortage of painters comes from a help-wanted advertisement for “Painters in Blue and White,” placed by the Worcester factory in 1761.[14] Wedgwood’s letters to his partner Bentley made several references to looking for painters and the possibility of establishing a training school that would be needed after they opened an enameling shop in Chelsea in 1769. Wedgwood asked Bentley to seek painters among the fan, coach, and fresco painters. Later that year, Wedgwood mentions looking for painters in Birmingham and suggests that they try to find painters at the Lambeth delft works.[15] In May 1770 Wedgwood wrote to Bentley concerning the recruiting and training of painters, underscoring the shortage of painters and the Staffordshire potters’ expanding need for them.

You observe very justly that few hands can be got to paint flowers in the style we want them. I may add, nor any other work we do. We must make them. There is no other way. We have stepped forward beyond the other manufacturers and must be content to train up hands to suit our purpose....We must be content to train up such Painters as offer to you and not turn them adrift because they cannot immediately form their hands to our new stile.[16]

The growing need for painters was a by-product of the success of Wedgwood’s creamware. The demand created by its brilliant marketing caused a fall in the demand for English porcelains. Weatherill’s estimates of the number of workers in the English pottery industry (see Table 1) show a drop in the number of porcelain workers from an estimated 450 in 1765 to 280 in 1770. During the same period, the number of fineware potters jumped from 1,333 in 1760 to 2,635 in 1770. In 1829, Simeon Shaw described the introduction of enamel-painted wares:

Workmen were soon employed from Bristol, Chelsea, Worcester, and Liverpool where Tiles had long been made of Stone Ware and Porcelain; and who had been accustomed to enamel them upon white glaze, and occasionally to paint them under the glaze. For some years the branch of Enamelling was conducted by persons wholly unconnected with the manufacture of Pottery; in some instances altogether for the manufacturers; in other on private account of the Enamellers; but when there was great demand for these ornamental productions, a few of the more opulent manufacturers necessarily connected this branch with the others.[17]

Blue painters were among those coming into Staffordshire from the porcelain factories. Worcester is one of the best-documented English porcelain factories. Many of the blue-painted, Chinese-style patterns produced by Worcester have been illustrated both in photographs and drawings.[18] The blue-painted patterns began to be replaced by underglaze blue-printed patterns in the 1760s.[19] Excavations of a Worcester waster pit produced a series of stratigraphic levels that clearly show the transition. Table 2 presents the percentages of blue-printed versus blue-painted levels from that excavation.

Table 2 Blue-Printed versus Blue-Painted Sherds from the Excavation of a Worcester Waster Pit.[20]

| Level | Dates | Painted | Printed |

| 18 | ca. 1757-58 | 90.0% | 10.0% |

| 17 | ca. 1758-60 | 86.8% | 13.2% |

| 15 | ca. 1760 | 87.5% | 12.5% |

| 13 | cz. 1765 | 72.0% | 28.0% |

| 8 | ca. 1775 | 22.8% | 77.2% |

Table 2 illustrates the rapid shift from painted to printed wares after the mid-1760s. The Caughley porcelain factory, founded in 1775, concentrated on printed patterns and produced very few blue-painted patterns.[21] The Caughley production appears to match that of Worcester after 1775. Worcester was using underglaze blue printing by the late 1750s. Staffordshire did not begin underglaze printing until the 1780s. Blue-painted wares became a major decorative type for the Staffordshire potters after they were almost abandoned by the porcelain potters in the mid-1770s.

R. W. Binns, writing in 1909, mentions a strike at the Worcester factory in 1770 that he learned about from his father. The strike by the blue painters was in response to the introduction of blue printing.[22]Unfortunately, contemporary documents about the 1770 shutdown have not survived. There is, however, a letter by Josiah Wedgwood to Thomas Bentley dated June 25, 1769, in which he mentions that “near twenty painters are just now discharged from Worcester, several had been to Derby but were not taken in. Some are come here.” Wedgwood goes on to describe an enameler named Willcox whom he had hired.[23] What relationship there may have been to the strike and the discharge of these painters is not clear. One factor was the change in technology; another could have been the stiff competition that creamware was giving the porcelain industry and its subsequent shrinking mentioned earlier. Wedgwood’s letter fits well with Simeon Shaw’s comment about the painters coming from “Bristol, Chelsea, Worcester, and Liverpool,” all porcelain-producing areas. The painters displaced by blue printing left for Staffordshire and were soon confronted with the same problem. Shaw wrote:

When Blue Printing was introduced, the enamellers waited upon Mr. Wedgwood to solicit his influence in preventing its establishment. We are informed that he religiously kept his promise, “I will give you my word, as a man, I have not made, neither will I make any Blue Printed Earthenware.”[24]

This was a promise he kept. Hugh Owen’s history of the Bristol pottery industry has an interesting parallel story about the introduction of blue printing:

When printing was first introduced in Water Lane, one of the painters, apprehensive that the new art would injure the enameller’s trade, became despondent and drown himself. This cup was his last work it is marked “J. Doe. Sept. 1787.”[25]

The building of a furnace for the refining of cobalt facilitated production of blue-painted wares in Staffordshire. According to Simeon Shaw, a man named Roger Kinnaston was given the knowledge for the refining of cobalt by William Cookworthy and he set up a furnace in Cobridge in 1772. Shaw stated that Kinnaston “sold copies of the recipe for trifling sums, £10. or £12...to gratify his Bacchanalian propensities.”[26] Thus the knowledge of how to refine cobalt became readily available to a number of potters and color makers.

By 1770 the market was glutted with ceramics, another factor that probably hastened the development of blue-painted earthenwares. The first Staffordshire potters’ price-fixing agreement was written that same year. The 1770 agreement of the salt-glazed stoneware potters set the price of the wares to be sold to the earthenware potters, who had become the dominant force by that time.[27] By 1771 the Staffordshire potters were beginning to see price-cutting, and they attempted to come to an agreement on prices. In April of that year, Wedgwood, writing to Bentley about price-cutting in the potteries, stated:

Mr. Baddeley who makes the best ware perhaps of any of the potters here, and a ovenfull of it Per Diem, has led the way, and the rest must follow unless he can be prevailed upon to raise it [his prices] again, which is not probable, though we are to see him tomorrow, about a dozen of us, for that purpose....Mr. Baddeley has reduced the prices of the dishes to the prices of white stone.[28]

One result of the meeting with Baddeley was the reinstatement of the higher prices. Another result was the formation of the Potters Manufacturers Association for which Wedgwood was asked to “draw up a sort of preamble and a few articles to bind us together.”[29] The earliest known price-fixing agreement listing the cost of creamware dates to 1787 and shows that prices continued to decline.[30] Given an oversupplied market and the changes that had taken place prior to 1770, the potters were looking for a product that would have more of a market and bring a better price for their efforts. That product was China glaze.

China Glaze

China glaze was a copy of Chinese porcelain via the filter of English porcelain. The painted chinoiserie patterns on Staffordshire earthenware are not as detailed as those produced by Worcester, Bow, Chelsea, Caughley, or Lowestoft that preceded them; however, they found a much broader market at a cheaper price. In the ninth chapter of his history on the rise of the Staffordshire pottery industry, Simeon Shaw described the industry’s ascendance in the 1770s:

The Manufacturers of the district generally were now excited to unremitted exertions, and these with their previous knowledge, produced those various improvements which have brought the Pottery into repute. The superior kinds now became the medium of ornamental devices; at first in mere outline, and blue painted, rude and coarse; imitation of the foreign China, and gradually improved to fine delicate designs. A specimen is preserved of a quart mug, with a bluish glaze, which was painted by Dan[iel] Steele, in Blue, and well exhibits the defective nature of the process at that time.[31]

Shaw does not give a date for Daniel Steele’s mug or the introduction of blue painting. He speaks of a great demand for painted and enameled pottery, causing the potters to use glue bat overglaze prints as outlines for the painters. Daniel Steele was one of the earliest potters to use this form of painting, which was introduced into the Staffordshire potteries around 1777.[32]

The demand for cobalt caused its price to go up considerably. A letter from Wedgwood to Bentley in March 1777 mentioned that a pound of cobalt cost thirty-six shillings. In November of the same year, the price had gone up to sixty-three shillings a pound, a 75 percent increase in price.[33] This may be a reflection of the great demand noted by Shaw and demonstrates that China glaze wares were on their way.

China glaze copied Chinese porcelain in four ways: (1) the duplication of Chinese painted patterns, (2) vessel shapes like the Chinese tea bowl shape and undercut foot rings, (3) the blue-tinted glaze giving the wares the look of Chinese porcelain, and (4) the name “China glaze.” It is likely that China glaze production began in Staffordshire around 1775, when all of the necessary elements came together and the extension of the Champion patent prevented the potters from producing porcelain. Unfortunately, we have neither an exact date for its appearance, nor can we credit any potter or group of potters with its development.

Summary of the Changes that Led to the Development of China Glaze

1. The quest for the secret of making porcelain brought new materials into the pottery industry such as kaolin, Growan stone, calcined bone, flint, and white-firing clays.

2. Publication in English of Père D’Entrecolles’s description of how the Chinese made porcelain unlocked several mysteries of that process.

3. Open access to kaolin and Growan stone, and the establishment of a cooperative to bring these materials to Staffordshire in 1774, encouraged experimentation with the new materials.

4. The extension of Champion’s patent prevented the potters from making porcelain with these specified materials, causing them to produce a close imitation of Chinese porcelain, i.e., China glaze.

5. The 1772 establishment of a furnace for refining cobalt in Cobridge made another one of the key ingredients more readily available to the Staffordshire potters.

6. The 1760s transition from blue-painted to blue-printed patterns in the English porcelain factories led painters to seek employment in Staffordshire. The displaced blue painters were already trained in rendering Chinese-style patterns.

7. The success of creamware in the 1760s, due to Wedgwood and Bentley’s marketing, was the death knell for the British delft industry. Creamware production reduced the market for English porcelain, adding to the influx of painters to Staffordshire.

8. By the 1770s, creamware was an old product in a glutted market. Prices were falling and the potters, to survive, needed a new product. That new product was China glaze, which was probably in production by at least 1775, if not a few years earlier.

How China Glaze Came to be Called “Pearlware”

Ceramic scholars and collectors have generally used the term “pearlware” to classify the China glaze wares. The names “China glaze” and “pearlware” dropped out of usage and were forgotten by the end of the eighteenth century; the terms did not come back into vogue until well into the twentieth century when collectors, historical archaeologists, and ceramic scholars began to take an interest in these wares.

References to “China glaze” and “pearlware” are very rare in nineteenth-century pottery documents and histories. For example, neither term appears in any of the eleven extant Staffordshire potters’ price-fixing lists.[34] “China glaze” was a common term in the 1784 edition of Bailey’s Directory of the Potteries of Staffordshire. Ten potters in that directory name themselves as producers of China glaze in addition to cream color, or Queen’s ware. None of the potters was listed as producing pearlware. Unfortunately, the later Staffordshire directories are less detailed and generally only list earthenware or porcelain, rather than types of ware.[35]The terms “China glaze” and “pearlware” are, with a few exceptions, absent from potters’ and merchants’ invoices and correspondence. The terms are also absent from American probate records and newspaper advertisements.[36] Even the early collections of potters’ recipes do not mention the terms “China glaze” or “pearlware.”[37] And they are, for the most part, missing from the classic nineteenth-century references (i.e., Shaw, Ward, Jewitt, Chaffers, and Meteyard).[38] Even important twentieth-century authors, such as Towner and Hillier, do not have much information on these wares other than attributing the invention of pearlware to Josiah Wedgwood in 1779.[39]

The Selected Letters of Josiah Wedgwood, edited by Finer and Savage in 1965, provides easy access to Wedgwood’s letters to Thomas Bentley, which record the development of “Pearl White.” Three letters to Bentley by Wedgwood in 1779 have provided the main proof of Wedgwood’s invention and introduction of pearlware that year.[40] One of the first scholars to give a detailed summary of the available information on pearlware and China glaze was Ivor Noël Hume in his seminal article “Pearlware: Forgotten Milestone of English Ceramic History.”[41] For historical archaeologists working on sites occupied in the late eighteenth and the early nineteenth centuries, the predominance of these blue-tinted wares guarantees that they cannot be ignored. The 1779 date that introduced Wedgwood’s Pearl White became the terminus post quem for any context containing these wares.

Supporting evidence for Wedgwood as the developer of this blue-tinted glaze emerges from a manuscript biography of Josiah Wedgwood. The manuscript heading reads “Compiled by Mr. John Leslie, now Professor of Mathematics at Edinburgh, from a sketch drawn up by the late W. Byerley and written before 1800.” John Leslie was the tutor and companion to Josiah’s son Thomas Wedgwood from 1790 to 1792.[42] Unfortunately no other reference to a W. Byerley has been found—only a reference to Thomas Byerley, a nephew of Josiah Wedgwood who was taken in as a partner by Josiah in 1790.[43]

The biography discusses the development of a blue-tinted glaze by Wedgwood after he developed Jasperware circa 1775.[44] The text of the manuscript states that Wedgwood worked toward improving his Queen’s ware by whitening it and “invented a white glaze of a bluish cast...as practiced in the fabric of the oriental porcelain.”[45] This glaze was used on the underglazed blue-shell edge. Leslie goes on to say that this improvement was not well received and that the new ware was considered as a mere imitation of the porcelain wares. Leslie seems to imply that Wedgwood dropped the ware from production. He then goes on to state:

But the idea was not lost in the Pottery. His ingenious neighbors afterwards adopted the white glaze which acquired the name of China glaze. They pursued and extended the discovery even beyond its original object insomuch as to cover the whole surface of the ware in blue paintings resembling the Chinese....This white or China glaze was produced by means of some clays from Cornwall and Devonshire unknown before in the Pottery.[46]

Interestingly, the term “pearlware” or “Pearl White” does not occur in Leslie’s manuscript. The manuscript also credits Chinese porcelain as the impetus for the development of a blue-tinted glaze that Wedgwood and the other potters were copying. The mention of the Cornwall and Devonshire clays also helps place the event after 1774, when the right to use these materials was gained after Champion’s patent was renewed.

While the biography indicated that Wedgwood’s improved blue-tinted glaze preceded China glaze, there is good evidence that this was not the case. The most meaningful indication that the order was reversed comes from both a combination of Wedgwood’s letters to Bentley and evidence from archaeological sites. Unfortunately, Bentley’s letters to Josiah Wedgwood have not survived, so we only have half of the correspondence on the development of their Pearl White. From Wedgwood’s letters to Bentley, it is clear that Bentley was putting some pressure on him to produce a whiter firing ware. For example, in Wedgwood’s letter of January 14, 1776, he responds to an enquiry from Bentley by stating that “But for Useful China, or such a white-ware as you mention, I must beg a longer time.” He goes on to say that he wants to finish the development of Jasperware before turning his attention to the development of a white ware. Further, he wrote:

You know very well that from the moment a finer ware than the Cream-color is shewn [sic] at our Rooms, the sale of the latter will in great measure be over there....I have not yet been able to take one step of any consequence toward making the useful ware, but I now intend to begin in earnest upon this subject.[47]

Pressure for a new white ware was increasing. Wedgwood’s letter of April 18, 1778, stated:

We are perswaded [sic] that the diminution of our sales...is owing chiefly to the very great difference between the price of our Queens ware (which is no longer that choice thing it used to be, since every shop, house, and cottage is full of it) and other people’s and that without lowering the prices very considerably we shall not be able to continue our business.[48]

Under these pressures, Wedgwood finally produced his whiteware in 1779. In a letter at the end of February, Wedgwood asked Bentley to come up with a name for his new ware, and by June of 1779 they had settled on “Pearl White.”[49] While they had their new Pearl White, they were not happy with the ware. In his letter to Bentley dated August 6, 1779, Wedgwood states:

Your idea of creamcolour having the merit of an original, and the pearl white being considered as an imitation of some of the blue and white fabriques, either earthenware or porcelain is perfectly right, and I should not hesitate a moment in preferring the former if I consult my own taste and sentiment....The pearl white must be considered as a change rather than an improvement, and I must have something ready to succeed it when the public is palled.[50]

Wedgwood’s Pearl White did not come onto the market until late in 1779. The evidence suggests that the majority of the Pearl White produced was wares in the shell edge pattern. Robin Reilly’s recent history of Wedgwood makes the comment that:

[l]ittle of Wedgwood’s work during the eighteenth century shows signs of Chinese influence....Josiah was never interested in making blue-and-white, partly no doubt because there was already too much of it available from the earthenware and porcelain manufacturers....[H]e appears to have had little taste for ceramics decorated in this type of ware.[51]

We have not recorded a single vessel produced by Wedgwood painted in a chinoiserie style with a blue tinted glaze.

Now let us consider the evidence for China glaze predating pearlware. The earliest recorded use of the term “China glaze” is from a 1783 invoice for some “green shell edged china glaz’d” plates sent to Tappahanock, Virginia.[52] The term China glaze was also used in the 1784 Bailey’s Directory of the Potteries of Staffordshire, already discussed. Two interesting persons describing themselves as producing cream color and China glaze are Thomas Wedgwood of the Big House and Thomas Wedgwood of the Over House potteries.[53]

Thomas Wedgwood was a pretty common name during this period. In addition to these two Thomas Wedgwoods, there was of course Josiah’s partner and cousin, Thomas Wedgwood, who was also known as “useful Thomas.” The two Thomas Wedgwoods working in Burslem were distant cousins of Josiah Wedgwood, which makes their use of the term “China glaze” interesting. This suggests that Pearl White was probably limited to the products produced by Josiah Wedgwood and his partners and was not used by the other potters, even those related to Josiah.

The other dated reference for China glaze is a jug in the Victoria and Albert Museum that Noël Hume describes as a blue-painted pearlware jug with a black overglaze inscription that reads “A Butcher/A D 1777.” In his article on pearlware, Noël Hume states that this date was applied sometime after 1779 because it could not predate Wedgwood’s introduction of pearlware.[54] Given that China glaze predates pearlware, the 1777 date may be a good one, especially considering the preceding “A.D.”

All of the evidence presented up to this point has been a series of circumstances and events that would have led toward the development of China glaze. What has been missing is evidence of pre-1779 blue-tinted glazed earthenware, a gap that has now been filled.

John Seidel’s article on China glaze from American Revolution sites lists two occurrences that predate Wedgwood’s introduction date. In one case, China glaze sherds were recovered from the wreck of the Defensethat sank off the coast of Maine in August 1779. As Seidel notes, “Given the fact that Wedgwood was still trying to name his new white-bodied ware in August of 1779, the Defense find is surprisingly early.” The second context was two China glaze sherds retrieved from the HMS Orpheus, which sank in August 1778.[55] These two finds clearly establish that China glaze predates Wedgwood’s Pearl White or pearlware.

Perhaps the strongest evidence that China glaze may have been produced as early as 1775 comes from David Barker’s excavation of potter William Greatbatch’s waster tip in Fenton, Stoke-on-Trent. The waster tip contained wares that spanned the length of his potting operating between 1762 and 1782, including large quantities of blue-painted China glaze sherds with numerous variations on the Chinese house pattern. Greatbatch had gone bankrupt in 1782, just three years after Wedgwood’s introduction of Pearl White. However, given the quantities of China glaze that were produced by Greatbatch, Barker concurs that a circa 1775 development date for China glaze is “most welcome and reassuring.”[56]

The Significance of China Glaze in the Development of English Ceramics

This paper is rather a long patchwork of isolated bits of information that we have pulled together to gain insight into the development of the English ceramics industry. It is not about moving the date of pearlware back a very few years or trying to take anything away from Josiah Wedgwood’s incredible contribution to the development of the English ceramic industry. For far too long, those interested in ceramic history have been using simplistic descriptions of changes that took place by using such statements as “pearlware replaced creamware.” That misses the importance of what happened.

China glaze and pearlware did not replace creamware: decoration replaced creamware. The vast majority of creamware is undecorated. China glaze and pearlware are almost never undecorated. The reasons the terms “China glaze” and “pearlware” were forgotten was because these wares became known by how they were decorated. They became “painted,” “edged,” “printed,” or “dipt” wares. The decoration was what determined the price of these wares, and it became the handle by which they were referred to in potters’ price-fixing lists, invoices, merchants’ account books, price lists, and catalogs.[57] Collectors, archaeologists, and ceramic historians have put an emphasis on the ware types, which is what the potters and their customers dropped in favor of a decoration terminology.

The differences between creamware and China glaze and/or pearlware are also important in terms of what it meant to the Staffordshire potteries. Creamware was a breakaway product that set the pace for at least two decades. Through the brilliant marketing of Wedgwood and Bentley, with sales to Queen Charlotte and Catherine the Great, they were able to raise an earthenware to a level where it competed with porcelain. Yet, undecorated creamware was affordable for the common household. Indeed, creamware actually cut into the sale of English porcelain and affected the development of the English porcelain industry. China glaze or pearlware was, in the words of Josiah Wedgwood, “an imitation of some of the blue and white fabriques” and as a copy it was never going to be able to compete with porcelain in status. The blue-painted chinoiserie patterns the Staffordshire potters picked in the 1770s were those that the English porcelain potters were using at least twenty years before and now abandoning. In the same way, the Staffordshire potters adopted underglaze printing almost two decades after the English porcelain factories were using it. Later, when bone china became popular, the earthenware potters switched to making the ware that we call whiteware.

Where does China glaze end and pearlware begin? How many angels can dance on the head of a pin? Defining China glaze will always be a problem; however, we venture to suggest that China glaze wares be defined as those earthenwares that have a blue-tinted glaze, are decorated in Chinese-style patterns, and copy such Chinese vessel forms as the Chinese tea bowl shape and undercut foot rings.

Using that definition, it would appear that China glaze dates from circa 1775 to circa 1812 for American sites. There are later examples, such as a jug dated 1821 with a blue-painted Chinese house pattern, but they are outliers on the bell curve. Blue-printed wares with Chinese-style patterns were in production on China glaze for a longer time than the blue-painted China glaze wares. Most of the China glaze wares that fit this definition from American archaeological sites are cups and saucers, teapots, bowls, and jugs. There are some shell-edged plates with Chinese house patterns, but they seem to lose out to blue-printed patterns by around 1800. Other blue-tinted wares with floral motifs, plain shell-edged wares, and dipt wares could be called pearlware. This classification has some problems, but it will give more chronological control than calling everything “pearlware” and will give some acknowledgement of how these wares evolved.

Recognizing the term “China glaze” also forces us to acknowledge the incredible stylistic contribution of Chinese culture. The love affair with Chinese porcelain has continued for centuries. The incredible innovations of the English defltware, earthenware, and porcelain potters can be attributed to consumers’ lust for something in the Chinese style. Josiah Wedgwood found his inspiration in Greek and Roman antiquities, and helped create a new market for things in the neoclassical taste. He named his pottery the “New Etruria,” which was a further statement of his commitment to the classical style. The Bow porcelain factory on the other hand was named the “New Canton,” which reflected the Chinese style that they and the other early English potters produced. It is ironic, in so many ways, that the term “pearlware,” coined by a potter who made virtually nothing in the Chinese style, has usurped the very meaning embodied in the name “China glaze.”

Acknowledgments

The research and the provision of time in which to gather the information were greatly facilitated by two NEH grants to George Miller (now archaeological laboratory director at URS Corporation) for research on the development of the American market for English ceramics in America. Those grants were National Endowment for the Humanities numbers ro-21158-86 while he was an employee of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, and rk-20004-93 while he was an employee of the University of Delaware Center for Archaeological Research. The first grant enabled Miller to spend three months in Staffordshire doing research in the Wedgwood, Spode, Minton, and other archives. This research in England was greatly facilitated by Robert Copeland, Gaye Blake Roberts, Pat Halfpenny, Martin Phillips, David Barker, Rodney and Eileen Hampson, Terry Lockett and was also dependent on information gathered during two NEH Winterthur Fellowships, one in 1979 and one in 1991. The Winterthur Museum Library and the Downs Manuscript Collection have very extensive and well-indexed collections of rare books and manuscripts. Their usefulness is greatly enhanced by the head librarians, Neville Thompson and Richard McKinstry, who are wonderfully knowledgeable about the collections. These collections have been great resources while doing this research. Many colleagues have contributed to our research by pointing out examples of early China glaze and pearlware and references for our research. We would like to thank Garry Atkins, Lee and Joyce Hanes, Ivor Noël Hume, Lynne Sussman, and Arlene Palmer. We would especially like to thank once again Rodney Hampson for his careful reading of our paper and for pointing out areas that needed our attention and correction.

William Burton, Porcelain: Its Nature, Art, and Manufacture (London: B. T. Batsford, Ltd., 1906), p. 172.

Reference to Du Halde’s history and its publication in English was taken from Ann Finer and George Savage, eds., The Selected Letters of Josiah Wedgwood (London: Cory, Adams & MacKay, 1965), p. 162.

Kenneth Hudson, The History of English China Clays: Fifty Years of Pioneering and Growth (Newton Abbot, England: David and Charles, 1969), p. 16.

Bernard Watney, English Blue and White Porcelain of the 18th Century (New York: Thomas Yoseloff Publisher, 1964), p. 125.

Ibid., pp. 119–22.

Ibid., p. 122.

Geoffrey A. Godden, Godden’s Guide to Ironstone, Stone and Granite Wares (Woodbridge, Suffolk, England: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1999), p. 57.

Finer and Savage, Selected Letters, pp. 179–81.

Ibid., p. 186.

Watney, English Blue and White Porcelain, p. 123.

Finer and Savage, Selected Letters, p. 179.

Lorna Weatherill, The Growth of the Pottery Industry in England: 1660–1815(New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1986), p. 451, table a1-7.

John Bedfor, Chelsea and Derby China (New York: Walker and Co., 1967), pp. 9–10.

Lawrence Branyan, Neal French and John Sandon, Worcester Blue and White Porcelain: 1751–1790 (London: Barrie & Jenkins, 1981), p. 16.

Finer and Savage, Selected Letters, pp. 79, 84.

Ibid., p. 92, letter from Josiah Wedgwood to Thomas Bentley, 19 May 1770.

Simeon Shaw, History of the Staffordshire Potteries; and the Rise and Progress of the Manufacture of Pottery and Porcelain; with References to Genuine Specimens, and Notice of Eminent Potters (Hanley, Staffordshire, England, 1829; reprint, Great Neck, N.Y.: Beatrice C. Weinstock, 1968), p. 178.

Branyan, French and Sandon, Worcester Blue and White Porcelain.

Ibid., pp. 17–20.

Ibid. Table 2 was taken from p. 20.

Geoffrey A. Godden, Caughley and Worcester Porcelains: 1775–1800 (Woodbridge, Suffolk, England: Antique Collectors’ Club, Ltd., 1981), p. 15.

Branyan, French, and Sandon, Worcester Blue and White Porcelain, p. 17.

Finer and Savage, Selected Letters, p. 75.

Shaw, History of the Staffordshire Potteries, pp. 192–93.

Hugh Owen, Two Centuries of Ceramic Art in Bristol: Being a History of True Porcelain by Richard Champion with a Biography compiled from Private Correspondence, Journals, and Family Papers (Bristol, England: Bell & Dalby, 1873), pp. 353–54.

Shaw, History of the Staffordshire Potteries, p. 221.

This list was reproduced in Shaw, History of the Staffordshire Potteries, pp. 207–208, and in Arnold Mountford, “Documents Relating to English Ceramics of the 18th and 19th Centuries,” Journal of Ceramic History 8, no. 99 (1975): 4–8.

Finer and Savage, Selected Letters, p. 106.

Ibid., p. 108.

“Prices of queen’s ware or cream coloured earthenware, established through the Potteries, from February 2d, 1787”: a printed list bound with The Ruin of Potters, and the Way to Avoid it (Lane-end, Staffordshire, England: T. Orton, 1804).

Shaw, History of the Staffordshire Potteries, p. 210.

Ibid., p. 212.

Finer and Savage, Selected Letters, p. 204.

Extant price-fixing lists for the Staffordshire potters are known for the years 1770, 1783, 1787, 1795, 1796, 1808, 1814, 1825, 1846, 1853, and 1859. These price-fixing agreements are discussed in George L. Miller, “A Revised Set of CC Index Values for Classification and Economic Scaling of English Ceramics from 1787 to 1880,” Historical Archaeology 25, no. 1 (1991): 1–25.

I would like to thank Jonathan Rickard for providing me with copies of his abstractions from a collection (Barks Library, Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent, England) of fourteen StaVordshire directories dating from 1781 to 1828/29. Jonathan Rickard, “The Makers of Pottery and Porcelain in Staffordshire: 1781–1841” (unpublished manuscript).

Surveys of probate records for Plymouth County, Massachusetts, and Providence, Rhode Island, did not find any listing of pearlware or China glaze. Marley Brown, “Ceramics from Plymouth, 1621–1800: The Documentary Record,” Ceramics in America, edited by Ian M. G. Quimby, Winterthur Conference Report (1972) (Charlottesville, Va.: University Press of Virginia, for The Henry Francis duPont Winterthur Museum), pp. 41–74; and Barbara Gorely Teller, “Ceramics in Providence, 1750–1800,” Antiques 94, no. 4 (October 1968): 570–77.

The Valuable Receipts of the late Mr. Thomas Lakin, with Proper and necessary Directions for their Preparation and use in the Manufacture of Porcelain, Earthenware, and Stone China (Leeds, England: Edward Baines, 1824), printed for Mrs. Lakin; Simeon Shaw, The Chemistry of the several Natural and Artificial Heterogeneous Compounds used in Manufacturing Porcelain, Glass, and Pottery (1837; reprint, London: Scott Greenwood and Co., 1900); William Evans, Art and History of the Potting Business, compiled from the most practical sources, for the especial use of working potters, by their devoted friend, William Evans (Shelton, England: The Examiner Office, 1846), reprinted in Journal of Ceramic History, no. 2 (1970): 21–42.

Shaw, History of the Staffordshire Potteries; John Ward, The Borough of Stoke-upon-Trent (1843; reprint, Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent, England: Webberley, Ltd., 1984); Llewellynn Jewitt, The Wedgwoods: Being a Life of Josiah Wedgwood; Notice of his Works and their Productions, Memories of the Wedgwood and other Families and a History of the Early Potteries of Staffordshire (London: Virtue Brothers & Co., 1865); Llewellynn Jewitt, The Ceramic Art of Great Britain (1883; reprint, Poole, Dorset, England: New Orchard Editions, Ltd., 1985); Eliza Meteyard, The Life of Josiah Wedgwood from his Private Correspondence and Family Papers...With an introductory Sketch of the Art of Pottery in England, 2 vols. (1865–1866; reprint, Yorkshire, Eng.: Scolar Press, 1980); William Chaffers, Marks and Monograms on European and Oriental Pottery and Porcelain (1863; reprint, London: William Reeves, Bookseller, Ltd., 1965).

Bevis Hillier, Master Potters of the Industrial Revolution: The Turners of Lane End (London: Cory, Adams and MacKay, 1965); Donald Towner, The Leeds Pottery (London: Cory, Adams and MacKay, 1965)

The letters around the development of Wedgwood’s Pearl White are discussed in George L. Miller, “Origins of Josiah Wedgwood’s ‘Pearlware,’” Northeast Historical Archaeology 16 (1987): 83–95; reprinted in Thirty-Fourth Annual Wedgwood International Seminar: Pottery and Porcelain on Peach Street (Conference held in Atlanta, 1989), pp. 167–184.

Ivor Noël Hume, “Pearlware: Forgotten Milestone of English Ceramic History,”Antiques 95, no. 3 (1969): 390–397.

I am indebted to Rodney Hampson for sending me his article “The China Glaze,” which provides the information from John Leslie’s twenty-thousand-word biography of Josiah Wedgwood (Moseley manuscript wm 1127, Wedgwood Archives, Keele University, Keele, Staffordshire, England, n.d.). See Rodney Hampson, “The China Glaze,” Northern Ceramic Society Newsletter, no. 37 (March 1980): 11–12.

Finer and Savage, Selected Letters, p. 350.

Ibid., pp. 170–72.

Hampson, “The China Glaze,” p. 12.

Ibid.

Finer and Savage, Selected Letters, pp. 188–89.

Ibid., pp. 220–21.

Ibid., p. 231.

Ibid., p. 237. For a more detailed discussion of the pressure on Wedgwood to develop his whiteware, see Miller, “Origins of Josiah Wedgwood’s ‘Pearlware,’” pp. 83–95.

Robin Reilly, Wedgwood (London: McMillan, 1989), p. 99.

Ivor Noël Hume, “Corrections and Additions,” Antiques 96 (December 1969): 922.

Chaffers, Marks & Monograms, p. 29.

Noël Hume, “Pearlware,” p. 393.

John L. Seidel, “‘China Glaze’ Wares on Sites from the American Revolution: Pearlware before Wedgwood?” Historical Archaeology 24, no. 1 (1990): 82–95.

David Barker, William Greatbatch: A Staffordshire Potter (London: Jonathan Horne Publications, 1991), p. 167.

For a discussion of this, see Miller, “A Revised Set of CC Index Values,” pp. 1–25.