View of the Town of York Virginia from the River, 1754–1756. Colored drawing from Logbook #406 Voyage of HMS Success and HMS Norwich to Nova Scotia and Virginia. (Courtesy, The Mariner’s Museum, Newport News, Va.) William Rogers supplied popular taverns in Williamsburg as well as Yorktown

View of the Town of Gloucester York River Virginia, 1754–1756. Colored drawing from Logbook #406 Voyage of HMS Success and HMS Norwich to Nova Scotia and Virginia. Gloucestertown is located directly across from Yorktown on the north bank of the York River. (Courtesy, The Mariner’s Museum, Newport News, Va.)

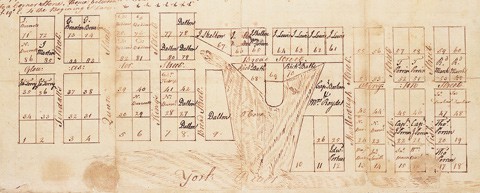

Miles Cary, Plat of Gloucester Town, 1707 (Robert Reade Thruston Papers; Filson Historical Society, Louisville, Ky.) Note Lots 7, 8, and 27.

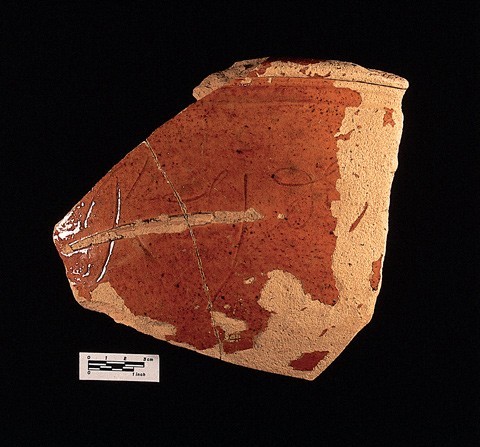

Fragment of a large bowl, William Rogers, Yorktown, Virginia, 1720–1745. Lead-glazed earthenware. This is the only known example of Rogers’s pottery inscribed with his name. (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Alain Outlaw.)

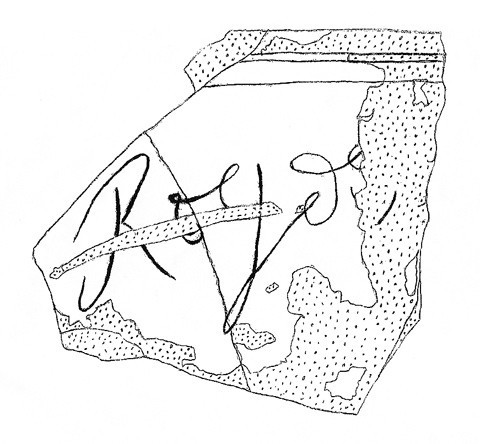

Drawing of the fragment illustrated in fig. 4 showing the “Rogers” inscription. (Drawing, Alain Outlaw.)

Pipkin, William Rogers, Yorktown, Virginia, 1720–1745. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 8 1/4". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resouces; photo, David Hazzard.)

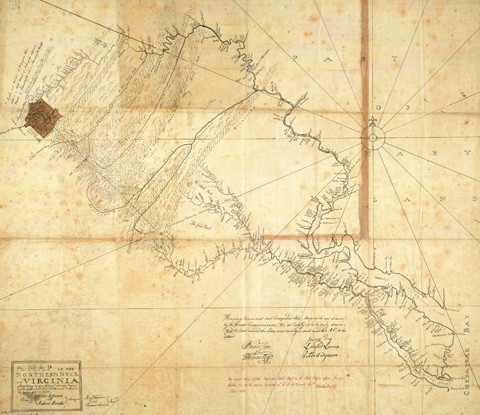

Peter Jefferson and Robert Brook, A Map of the Northern Neck in Virginia, 1713–1746. (Courtesy, The Library of Virginia.) Alexander Wordie transported Rogers’s wares from Yorktown to Wiccocomoco and then to Monokin, Maryland.

William Rogers, owner of the first Virginia pottery factory known to produce stoneware, resided in Yorktown. The extremely well-made salt-glazed stoneware and lead-glazed coarseware produced by his workers from 1720 until about 1745 were valued by consumers and enjoyed wide distribution. Shipping records suggest that these wares were exported to other North American colonies and perhaps to the West Indies.

The excavations that were undertaken between 1966 and 1982 by College of William and Mary archaeologist Dr. Norman Barka have culminated in the unearthing of William Rogers’s pottery factory and kiln complex. A subsequent analysis of the wares produced at this site resulted in the development of a typology (see Barka, “Archaeology of a Colonial Pottery Factory,” pp. 15–47 in this issue). Seminal research by historian Edward Ayres led to the identification of William Rogers as the owner of the Yorktown lot on which the pottery factory was located. Ayres also discovered that Virginia Governor William Gooch, when reporting to his superiors in England, purposefully downplayed the success of Rogers, whom he repeatedly referred to as the “poor potter.” In truth, Rogers lacked neither skill nor financial resources.

Although very little is known about William Rogers of Yorktown prior to his arrival in Virginia, it is certain that his older brother, George, was a collar maker and resident of Braintree, in Essex, in southeastern England. A pair of monogrammed silver salts and a can, embellished with the initials fpm, and six silver spoons engraved with the letters wtfr may provide clues to the identity of his forebears. Rogers came of age sometime prior to 1710 and married at least twice. When he made his will in 1739 he named as heirs his daughter Susanna, then a grown and married woman, and the three minor children he had with his wife Theodosia. William and Theodosia Rogers’s son, William Jr., came of age between December 1739 and May 1741, so he probably was born about 1720.[1]

Edward Ayres has raised the possibility that William Rogers was a native of London and that he may have come from Southwark, an area known for its pottery factories, particularly its manufactories of stoneware. This hypothesis is based on correspondence between his grandson and a cousin named Samuel Rogers, who was a Southwark merchant. On the other hand, shipping records strongly suggest that Rogers had close ties to Bristol merchants; he maintained business relationships there for at least three decades.[2] In 1700 a William Rogers was among those who shipped goods from England to New England aboard the Europe. In 1707 he sent a shipment to Virginia and Boston aboard the Virginia Merchant of Plymouth, England. Many of the destinations to which British merchant William Rogers sent merchandise were the same ones to which the Captain William Rogers of Yorktown later dispatched ships. This pattern of commercial activity suggests that William Rogers of Yorktown made frequent trips to England during his first few years in the colony, perhaps as a factor or agent of a British mercantile firm. Or he might have been working closely with a kinsman, perhaps his father or an uncle, whose name he shared.[3]

Around 1709–1710 William Rogers began making plans to set up housekeeping in Yorktown, a community established in 1691 (fig. 1). In December 1710 he was credited with importing an African slave aboard the Digges Frigate, a sailing ship that belonged to the Digges family of the Bellfield plantation in York County. On May 19, 1711, he acquired Yorktown Lots 51 and 55, which were contiguous. Rogers, whose deed identified him as a brewer, was obliged to build “a good house” on each of his vacant lots within twelve months. If he failed to do so, his property automatically reverted to the town trustees, who had the right to sell them. This proviso was intended to quell real estate speculation and stimulate development. By January 21, 1712, William Rogers had paid for his lots and obtained an unencumbered title to them, and it was there that he established a family home, a pottery factory, and some ancillary structures.[4]

Court records suggest that before he developed his own property, Rogers rented one or more buildings in Yorktown and conducted business as a brewer and merchant. In January 1712 the executors of mariner John Martin successfully brought suit against Rogers, alleging that “for more than 12 months past” he had been in possession of “sundry houses” that belonged to the decedent’s estate. On March 19, 1711, William Rogers was among the several York County men (most of whom were ordinary-keepers) who asked the county justices to set the rates that could be charged for various types of beverages. Rogers’s beer, which could be sold for 6 pence a quart, apparently was considered far superior to “Virginia Midling Bear” and cider, the price of which was set at only 3 3/4 pence per quart. However, English beer was worth twice as much as Rogers’s.[5] Rogers’s brewing activities most likely took place in or near one of the “sundry houses” that he was renting from John Martin’s estate, probably near the waterfront.

During the 1710s William Rogers frequently served as an agent of York County’s court justices. This suggests that he was considered trustworthy and astute, and was a respected member of the community. Rogers often was called upon to appraise decedents’ estates, serve as a juror, audit business accounts, and take witness testimony. Later, he served as captain of a troop of horse soldiers and even was responsible for seeing that a new county jail was built. Apparently he was not a deeply religious man, for he was fined on account of his chronic absences from church, a legal obligation in colonial Virginia, which had an officially sanctioned state church.[6]

Although it is unclear what impelled William Rogers to build a pottery factory, it is likely that as a savvy businessman he seized the opportunity to capitalize on local tavern-keepers’ constant need for vessels. (Rogers’s role as security for Williamsburg tavern-keeper Edward Ripping in 1714 would have reinforced his awareness of this potential market.) The relationship between the brewer’s and potter’s trades seems to have been a long-standing one. During the mid-seventeenth century there were at least three brew houses in Jamestown, the capital city, which had an abundance of taverns. Near at least one of these sites, archaeological evidence has been found that demonstrates that an apothecary, a brewer, and a potter were at work. One man known to have gone from one occupation to the other is Christian Whithelm, who was a brewer when he moved to London during the 1630s, but by the 1640s had become an apothecary and potter.[7] Apparently, those who needed substantial quantities of containers sometimes decided to make them.

In 1725 William Rogers sold a large quantity of earthenware to John Mercer, an Irishman and trader who settled on the Potomac River at Marlborough Town. Mercer began acquiring lots and continued until he had purchased much of the town. He built a mansion and constructed a mill, brewery, and glass factory. He also had a wharf, several warehouses, and a tavern.[8] This diversity in entrepreneurial activities, similar to the economic strategy employed by William Rogers, offered the assurance of good and reliable income.

In 1734 William Rogers became the official surveyor of Yorktown’s landings, streets, and causeways, which he was obliged to keep in good repair. Archaeologists discovered in 1957 that Rogers sometimes used pot sherds to fill in low places in Yorktown’s streets. Layers of Rogers stoneware sherds, several inches deep, were found beneath Main Street in front of Yorktown’s Digges House. The technique of using potters’ refuse to make a firmer base or roadbed is well documented in England.[9]

Historical documents reveal that white indentured servants and enslaved Africans and African Americans worked together in William Rogers’s pottery factory at Yorktown. In December 1710 he paid for the transportation of a male African slave, named London, from London to Virginia. During the early to mid-1720s he purchased several young slaves, boys and girls between the ages of nine and fourteen. All of these children, to whom Rogers gave English names, came from Africa and arrived at Yorktown aboard sailing vessels that originated in Bristol or London.[10]

William Rogers also employed white indentured servants (or contract workers) in his pottery factory. Because he dealt regularly with merchants in Bristol and London, he would have been able to draw upon a labor pool that included workers with specialized expertise, and he may have deliberately sought someone who had the potter’s skill. It is possible that one or more of the men and women whose contracts Rogers bought had a working knowledge of pot-making and would have been able to train others. William Rogers himself may have had some knowledge of the potter’s craft.

The identities of seven of William Rogers’s indentured servants are known because they ran afoul of the law and were brought before the justices of the county court. At least three had been sent to Virginia as convict servants.[11] Documents on file in the British Public Records Office reveal that during the early 1720s Rogers bought the contracts of male convicts from Middlesex (in the immediate vicinity of London), Yorkshire, and Devon. He may have purchased others, perhaps selectively. Advertisements that appeared in the Virginia Gazette during the eighteenth century attest to the wide variety of occupational skills to be found among Virginia’s convict servants, and certainly those with specialized skills would have been in great demand despite their questionable pasts.

Throughout the years William Rogers’s pottery factory was in business he had problems with his indentured servants. In August 1739 William Barbasore was jailed for breaking into two local storehouses, one of which belonged to his master. When confronted by his accusers, Barbasore admitted that he and another indentured servant (a blacksmith) had broken into Rogers’s store and stolen two or three butter pots and a stoneware saucepan that they had carried off and sold. On another occasion the same two burglars robbed Rogers of fourteen pocket bottles. In both instances, the blacksmith had made keys for the purpose of unlocking the storehouses they intended to rob.[12]

A document dating to 1760 (two decades after William Rogers’s death) mentions his daughter’s not being entitled to a share of the profits from the wares produced at the pottery factory because she did not inherit the slaves.[13] This suggests that, at least by the end of his life, it was Rogers’s slaves who produced the ceramic wares in his Yorktown pottery factory—indicating, perhaps, that Rogers decided indentured servants with questionable backgrounds were too problematic.

During the summer of 1711, shortly after purchasing two Yorktown lots, William Rogers appears to have been among those responsible for dispatching goods from Bristol, England, to what was then Carolina aboard the galley Carolina. In mid-September 1715, Rogers, as the representative of William Hawksworth and Company of Bristol, had goods sent to Virginia aboard the Bristol Merchant. In 1716, trading as “William Rogers & Company,” Rogers dispatched shipments from Bristol to Pennsylvania and Virginia. Part of Rogers’s cargo was transported by the ship Abingdon, which belonged to a wealthy Virginia merchant and planter named William Dalton, who owned three waterfront lots in Gloucestertown, directly across the York River from Yorktown (figs. 2, 3).[14] Interestingly, archaeologists have discovered a large quantity of kiln furniture and pot sherds on one of Dalton’s lots, artifacts associated with William Rogers’s pottery factory (figs. 4-6).[15]

In late summer 1718 William Rogers dispatched goods from Bristol to Virginia aboard The Little York, a vessel that probably belonged to Yorktown, whose soubriquet was “Little York.” Court documents reveal that by 1725 Rogers was mass-producing ceramics. He had filed suit against Alexander Wordie, who was to transport a large quantity of earthenware to Maryland and sell it on consignment.[16] By 1730 William Rogers had become the registered owner of a Virginia-built sloop, the William and John, with John Kelsale as master. In 1730–1731 the sloop plied coastal waters and transported “18 doz. pcs. earthenware” to Maryland (fig. 7). Shipping records reveal that George Page transported earthenware from Yorktown to Maryland in his shallop, perhaps obtaining the ceramics locally. Peter Frazier, who cleared customs in Yorktown in 1732, carried “a parcel of earthenware” to Maryland, as did Virginia Gazette publisher William Parks, who took shipments of goods to Maryland in 1734 and 1735.[17] William Rogers was listed as the owner of a 150-ton ship, the Susanna, in 1732 (a vessel of that name had transported convict servants to Virginia in 1727). In May 1739, shortly before his death, Rogers advertised that he had a small shallop for sale at Yorktown.[18]

Shipping returns published in the Virginia Gazette between 1739 and 1745, when the William Rogers pottery factory was in the hands of his heirs, indicate that vessels transported stoneware from Yorktown to North Carolina on a fairly regular basis. The late C. Malcolm Watkins noted that Rogers’s stoneware may have been exported to New England, using as evidence Isaac Parker’s September 1742 petition to Massachusetts authorities for permission to establish a stoneware manufactory in Charlestown. Parker proffered that, “There are large quantities of said ware imported into this Province every year from New York, Philadelphia, & Virginia.” As William Rogers’s pottery works seems to have been the only stoneware factory in Virginia, it is likely that Parker was speaking of wares made in Yorktown. More specific information comes from the shipping records associated with the ship Friendship, which entered the York River naval district in December 1733 and left in February 1734, carrying “a parcel of Virginia made Earthenware.”[19]

However, Edward Ayres, who compared the quantities of ceramics being brought into Yorktown with the quantities being sent out, observed that more earthenware was being exported from Yorktown between 1725 and 1735 than between 1736 and 1740, when New England traders were more active. Pottery exports from Yorktown increased between 1741 and 1745, the years during which the late William Rogers’s son-in-law was in possession of the lots on which the Rogers manufactory was located. Shipping records also reveal that the majority of the sailing vessels that left Yorktown with ceramics went to Maryland and North Carolina and that only a few went to New England and the West Indies.[20]

During the first quarter of the eighteenth century England had an aggressive protectionist policy regarding its manufactured goods. From the British perspective, the colonies existed for the Mother Country’s benefit and they were expected to support England’s mercantile system. To encourage dependency, the production of goods in the British colonies was discouraged. Included in the town acts passed by the Virginia Assembly between 1680 and 1705, intended to promote urban development, were economic incentives designed to attract those who engaged in crafts and trades. English officials opposed these acts, because they believed that encouraging manufacturing by the colonists would “take them off from the Planting of Tobacco, which would be of very ill consequence, not only in respect to the Exports of our Woolen and other Goods and Consequently to the dependence that Colony ought to have on this Kingdom.” They proffered that the promotion of manufacturing would also be “a further Prejudice in relation to our shipping and navigation.”[21] Thus, when William Rogers established his pottery factory in Yorktown, it was at a time when the colonists were discouraged from producing manufactured goods, especially those that might compete with commodities being exported by the Mother Country.

From 1700 on, Virginia’s governors were asked to submit reports to the Commissioners for Trade and Plantations and to the Board of Trade, documenting the extent to which the colonists were producing marketable commodities. In 1713 Lieutenant Governor Alexander Spotswood, who had brought skilled German workers to the colony to establish an ironworks, reported that the decline in the colony’s tobacco trade was due to the crop’s low value. He added that “Unless a remedy is found the colony will be forced to turn to the manufacture of other goods.” Spotswood noted that the “decay of the Tobacco trade” had led to “the collapse of the colony as a market for British manufactures.”[22]

Lieutenant Governor William Gooch, who acted as the colony’s chief executive from 1727 to 1749, was very sympathetic to the colonists’ economic plight but also politically savvy. His carefully worded, deprecating responses to official queries about manufacturing in Virginia veiled the increased industrial development that was occurring, thanks to population growth and the need for a ready supply of locally produced goods. Gooch’s offhand yet discreet references to Yorktown’s “poor potter” (William Rogers) exemplify this obfuscatory approach.

In 1732 Gooch stated that Virginia’s revenue laws were not prejudicial to British trade, and pointed out that there were fewer manufacturing enterprises in Virginia than in New England. He went on to say, “Nor indeed is there much ground to suspect that any kind of Manufactures will prevail in a Country where handycraft Labour is so dear.” He added, however, that “There is one poor Potter’s work of coarse earthen Ware, which is of so little Consequence, that I dare say there hath not been twenty Shillings worth less of that Commodity imported since it was sett up than there was before.” When Gooch was queried by his superiors a year later, he reported that “Wee have at York Town upon York River one poor Potter’s Work for Earthen Ware.” He stated that the potter’s production had not impinged upon British tax revenues, and that the only purchasers of the potter’s wares were “the poorest Familys . . . who not being able to send to England for such Things would do without them if they could not get them here.” Year after year Gooch downplayed the importance of the pottery works at Yorktown. In 1736 he said that “The same poor Potter’s work is still continued at York Town without any great Improvement or Advantage to the Owner, or any Injury to the Trade of Great Britain.” A year later Gooch commented that “The Potter continues his Business (at York Town in this Colony) of making Potts and Pans, with very little Advantage to himself, and without damage to Trade.” In 1739 he noted that “The Poor Potter’s operation” was unworthy of notice. Finally in 1741 he indicated that the “poor potter” was dead and that “the business of making potts & pans is of little advantage to his Family and as little Damage to the Trade of our Mother Country.”[23]

As time went on William Rogers prospered. In 1731 he purchased a twenty-five-acre tract at Terrapin Point, near Yorktown, an outlying parcel that he used as a quarter or farm (a practice common to town dwellers both in the colonies and in Europe). It was there that his slaves, working under an overseer, kept his livestock and produced food crops. In September 1738 Rogers bought Lot 75 in Yorktown, as well as some neighboring acreage upon which he commenced building a brick house for his eldest daughter, Susanna. He and wife Theodosia made plans to build a house next door. In March 1739 Rogers purchased Lot K within what was known as the Gwyn Read subdivision, which bordered south and east on original Yorktown and which was only a block away from the Rogers’s family home and pottery factory on Lots 51 and 55. A nineteenth-century reference to Lot K states that it was “a piece of land near an old clay hole on the back side of Yorktown.”[24] This raises the possibility that the site was the source of the clay Rogers used in pottery manufacturing.

When William Rogers made his will in May 1739, he identified himself as a merchant. He bequeathed his Yorktown lots and buildings (which would have included the family home and pottery factory) to his nineteen- or twenty-year-old son, William Jr., to whom he also left a warehouse on the waterfront, “under the Hill.” He also bequeathed to his son six enslaved males of African descent and an enslaved “India man,” probably a West Indian. It is likely that some or all of these men were associated with the pottery factory. William Rogers instructed his executrix, wife Theodosia, to see “that no potters ware not burnt and fit for Sale shall be appraised.”[25] This suggests that there was green ware on the premises at the time Rogers made his will and that he expected some to be present at the time of his demise.

The inventory of William Rogers’s estate reveals that a large part of his wealth was invested in his slaves. However, his personal possessions show that he was a wealthy, erudite man of refined tastes. When he died, he was in possession of fine furnishings, silver serving vessels, gilt-framed pictures, and other objets d’art. He also owned—in all probability, a reflection of his brewing activities—a copper cistern, a cold still, a worm still, some casks, beer tubs, hops, and 240 quart bottles. It seems likely, then, that Rogers continued to generate income as a brewer while actively producing ceramics.[26]

William Rogers Jr., who came of age in 1740 or 1741, died young. As he died unmarried and intestate, the legal interest in the real and personal property he had inherited descended to his father’s eldest brother, British collar maker George Rogers. He promptly conveyed his share of the Rogers estate to Thomas Reynolds, the husband of the elder William Rogers’s daughter, Susanna. From 1742 to 1760 Susanna and her half sister Sarah retained legal possession of Yorktown Lots 51 and 55, which contained the Rogers pottery factory and family home. However, a Hanover County document reveals that Thomas Reynolds came into possession of—and retained—at least four of the Rogers slaves and therefore was entitled to virtually all of the income that the pottery factory produced. An advertisement that appeared in the June 20, 1745, edition of the Virginia Gazette announced that a variety of imported goods was to be sold in Williamsburg, as well as “All sorts of Rogers Earthen Ware, as cheap as [in] York.” Shipments of Rogers pottery probably were being taken aboard vessels at Yorktown and transported to Maryland, for shipping returns dating to the summer of 1745 list “a parcel of earthenware.” When Thomas Reynolds died in 1759 he was still in possession of the slaves apparently associated with pottery making. This raises the possibility that pottery was being fabricated at the Rogers manufactory for ten or more years after the demise of its founder.[27]

York County Wills and Inventories 18 (1732–1740): 537–40; York County Orders, Wills, and Inventories 19 (1740–1746): 8. York County’s original colonial documents are on file in the York County Courthouse, Yorktown, Virginia; microfilms are available at the Rockefeller Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia.

York County Deeds, Administrations, and Bonds 5 (1741–1754): 64–66; York County Orders, Wills, and Inventories 19 (1740–1746): 193; Norman F. Barka, Edward Ayres, and Christine Sheridan, The “Poor Potter” of Yorktown: A Study of a Colonial Pottery Factory; Colonial National Historical Park, 3 vols. (Denver: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1984), 1: 18–19.

Peter Wilson Coldham, The Complete Book of Emigrants in Bondage, 1700–1750 (Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1992), pp. 11, 83, 127, 169, 180, 186–87, 218, 252, 487; British Public Records Office, London, Colonial Office Papers (hereafter C.O.) 5/1320, fol. 6.

Walter Minchinton, Celia M. King, and Peter B. Waite, eds., Virginia Slave-Trade Statistics, 1698–1775 (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1984), p. 41; York County Deeds and Bonds 20 (1701–1713): 365–66; York County Deeds, Orders, Wills 14 (1709–1716): pp. 82, 123.

York County Deeds, Orders, Wills 14 (1709–1716): 72–73, 119, 123.

Ibid., pp. 116, 119, 124, 136–37; 16, p. 575; 17, p. 74; York County Orders, Wills, and Inventories 15 (1716–1720): 14, 43, 86–89, 126, 357, 522.

Martha W. McCartney, Documentary History of Jamestown Island, 3 vols. (Williamsburg, Va.: National Park Service, 2000), 2: 106–22, 3: 396–37.

John Mercer, “Ledger Book, 1725–1732,” fol. 27, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va.; John W. Reps, Tidewater Towns: City Planning in Colonial Virginia and Maryland (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1972), p. 78.

C. Malcolm Watkins and Ivor Noël Hume, The “Poor Potter” of Yorktown (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1967), p. 92; York County Orders, Wills, Inventories 18 (1732–1740): 157A.

C.O. 5/1320, fol. 6; York County Orders, Wills, and Inventories 16 (1720–1729): 25, 59, 248, 280; 18 (1732–1740): 223; Minchinton, King, and Waite, Virginia Slave-Trade Statistics, pp. 49–51. When William Rogers made his will in 1739, several of these individuals were still part of the household; York County Wills and Inventories 18 (1732–1740): 553–57.

Some of the men and women transported to the colonies were habitual criminals; the majority, however, was not.

York County Orders, Wills, and Inventories 18 (1732–1740): 513–14.

John Snelson, Letter Book, 1757–1775, entry for July 5, 1760, microfilm, Rockefeller Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Dalton, who owned a plantation in Gloucester, sometimes sent shipments of pork, shingles, hams, pots of lard, beef, and beeswax to Barbados and Madeira. When William Dalton died, his widow, Sarah, married John Thruston, another Gloucestertown merchant, who owned Lot L in Yorktown’s Gwyn Read subdivision, next door to William Rogers’s Lot K (C.O. 5/1443, fol. 79; Polly C. Mason, comp., Records of Colonial Gloucester County, Virginia: A Collection of Abstracts from Original Documents Concerning the Lands and People of Colonial Gloucester County, 2 vols. (Newport News, Va.: Privately printed, 1946), 2: 58, 60.

Coldham, Emigrants in Bondage, pp. 11, 83, 17, 169, 180, 186–87, 218, 252, 487; Mason, Records of Colonial Gloucester County, 2: 58, 60; Miles Cary, Plan of Gloucestertown, 1707, Filson Club, Louisville, Ky.; David K. Hazzard, personal communication, April 2002.

York County Orders, Wills, and Inventories 16 (1720–1729): 380.

Parks established the Maryland Gazette in Annapolis in 1727 and then moved to Williamsburg, where he established a newspaper. Parks and his family owned property in both locations. He and Mrs. Sarah Packe of Williamsburg did business together and it is perhaps significant that Mrs. Packe and William Rogers sometimes transacted business; Martha W. McCartney, A Documentary History of the Hanover Tavern Tract (Williamsburg, Va.: Privately printed, 2002).

C.O. 5/1442, fol. 25; C.O. 5/1443, fols. 51, 68, 79–80, 102; C.O. 5/1444, fols. 1v, 12v; York County Orders, Wills, and Inventories 15 (1716–1720): 307, 317–18, 357–58, 388–89, 394, 439; Peter Wilson Coldham, English Convicts In Colonial America. Middlesex: 1617 - 1775, London: 1656 – 1775. 2 vols. (New Orleans, La.: Polyanthos, 1974 – 1976) 1: 304; William Parks, in Virginia Gazette (Williamsburg), May 4, 1739.

C.O. 5/1443, fols. 68, 79; Parks, in Virginia Gazette, June 24, September 21, November 2, 1739; January 24, 1741; July 4, 1745; Watkins and Noël Hume, “Poor Potter” of Yorktown, p. 84.

Barka, Ayres, and Sheridan, “Poor Potter” of Yorktown, 1: 174–77.

William W. Hening, ed., The Statutes at Large; Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia, . . . 13 vols. (Richmond: Samuel Pleasants, 1809–1813), 3: 404–5; William P. Palmer, ed., Calendar of Virginia State Papers and Other Manuscripts . . . Preserved in the Capitol at Richmond, 11 vols. (1875–1893; reprint, New York: Kraus Reprint, 1968), 1: 37–38 [emphasis added].

C.O. 5/1364, fols. 5–14; C.O. 5/1366, fols. 432–35.

C.O. 5/1323, fols. 62–66, 82, 93–94; C.O. 5/1324, fols. 3, 5–8, 20–21, 30–31, 59–60, 167–68.

York County Orders and Inventories 17 (1729–1732): 136; 18 (1732–1740): 478–80; York County Deeds, Administrations, Bonds 4 (1719–1726): 88–90; York County Deed Book 4 (1729–1740): 550–51; 21: 488–89; Robert Anderson, Papers, folder 319, Rockefeller Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

York County Wills and Inventories 18 (1732–1740): 537–40.

Ibid., pp. 544–45.

Parks, in Virginia Gazette, June 20, 1745; July 4, 1745; York County Orders, Wills and Inventories 21 (1760–1771): 99–102; John Snelson, Letter Book, 1757–1775, entry for July 5, 1760, microfilm, Rockefeller Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.