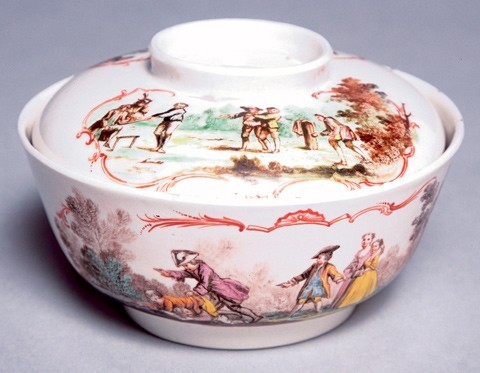

Covered bowl, East London, England, ca. 1744. Porcelain. H. 3 1/8". (Melbourne Cricket Club Museum Collection; courtesy of the National Sports Museum, Melbourne Cricket Ground. Acc. No. M569.1; photo, Erin O'Brien.) Decorated in enamels and marked on the base with an “A” in underglaze blue. This sugar bowl and cover, formerly in the Baer collection, are composed of a mixture of China clay and lime-soda frit in the proportion 60:40 (hydrous). This composition conforms to the 1744 patent of Heylyn and Frye, and it is proposed that whoever made this bowl was replicating the 1744 patent, which specified the use of Cherokee clay. This covered bowl is part of a partial tea set comprising a teapot and cover (see fig. 7), a cream jug, and three saucers.

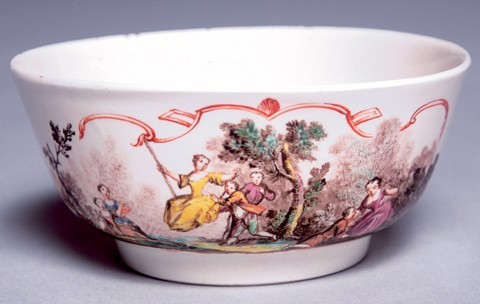

Side view of bowl illustrated in fig. 1. (Melbourne Cricket Club Museum Collection; courtesy of the National Sports Museum, Melbourne Cricket Ground. Acc. No. M569.1; photo, Erin O'Brien.) The vignette Swinging on the Rope, located on one side of the covered bowl, is derived from a set of engravings by James Cole titled The Second Part of Youthful Diversions, 1739. The palette comprises an iron red, as seen in the scrolled cartouche. In addition there is blue-green, grass green, vibrant mid-blue, brown grading to dark brown, black, purple, and shades of bright yellow either thickly applied, as on the girl’s skirt, or applied as a thin wash. Flesh pink is derived from mixing a buff color with very minor iron red. This range of colors is somewhat similar to the palette displayed on many early Bow phosphatic wares.

Side view of bowl illustrated in fig. 1. (Melbourne Cricket Club Museum Collection; courtesy of the National Sports Museum, Melbourne Cricket Ground. Acc. No. M569.1; photo, Erin O'Brien.) This vignette, Youth Sliding on the Ice, is located on the reverse side of the bowl and is also derived from James Cole’s The Second Part of Youthful Diversions, 1739.

Cover of bowl illustrated in fig. 1. (Melbourne Cricket Club Museum Collection; courtesy of the National Sports Museum, Melbourne Cricket Ground. Acc. No. M569.1; photo, Erin O'Brien.) Diam. 4 7/8". This scene, inscribed “YOUTH PLAYING AT CRICKET,” is derived from James Cole’s The Second Part of Youthful Diversions, 1739, and proved to be one of the main factors that led Charleston and Mallet in 1971 to propose a British rather than Continental origin for the A-marked group of porcelains.

Cover of bowl illustrated in fig. 1. (Melbourne Cricket Club Museum Collection; courtesy of the National Sports Museum, Melbourne Cricket Ground. Acc. No. M569.1; photo, Erin O'Brien.) View of the vignette Throwing at Cocks derived from Youthful Amusements, published by James Cole, 1740.

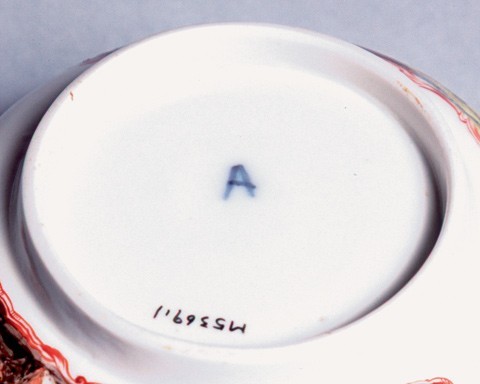

Base of the bowl illustrated in fig. 1. (Melbourne Cricket Club Museum Collection; courtesy of the National Sports Museum, Melbourne Cricket Ground. Acc. No. M569.1; photo, Erin O'Brien.) View of the “A mark,” which was painted in underglaze blue. It is the occurrence of this letter, either painted or incised, that characterizes the A-marked group. One line of thought has suggested that the A stands for the third duke of Argyll, who was a known patron of the arts at this time and had close links with the Bow manufactory. A more recent, alternative view is that the A commemorates Alderman George Arnold, who is generally regarded as being the financial supporter of the Bow manufactory during its infant years and, by inference, its supporter during the phase of manufacture of these porcelains.

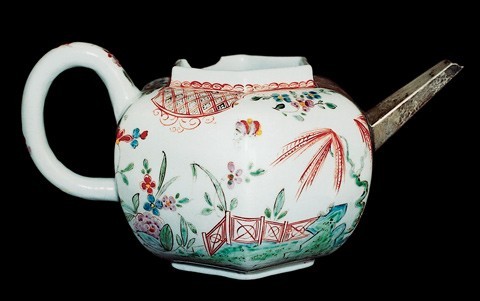

Teapot and cover, East London, England, ca. 1744. Porcelain, decorated in enamels and marked with an underglaze “A” in blue. H. 4 1/2". (© V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London, www.vam.ac.uk.) The scene shown on the teapot is taken from an engraving by George Bickham Jr. after Gravelot. This was based on the operetta Flora by John Hippisley, first produced on April 17, 1729.

Hexagonal teapot, Staffordshire, ca. 1730–1745. Lead-glazed redware with agate panels. H. 3 7/8". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This slip-cast hexagonal teapot exhibits applied press-molded agate panels of the Chinese-boy-in-a-tree design. A lion finial tops the lid. Examples such as this teapot suggest possible links between some A-marked forms (see fig. 12) and potters derived from Staffordshire.

Fluted cups, East London, England, ca. 1744. Porcelain. H. 2 5/8" and 2 3/8". (Courtesy, Seattle Art Museum, Dorthy Condon Falknor Collection of European Ceramics; photo, Susan Dirk.) The cup on the left is marked with an incised “A” and enameled in the Japanese Kakiemon-style quail pattern, which was used by Meissen, Bow, and, less commonly, by several other early English factories. The form of this slip-cast cup, with its twenty flutes originating from a decagonal low footrim, is a feature of A-marked cups. The white fluted cup on the right, with a somewhat primitive use of applied prunus blossom, leaf, and twig decoration, is one of two examples found occurring in the white and is inspired by a Chinese blanc de chine example. A feature characteristic of but not exclusive to early Bow phosphatic wares is the use of applied prunus blossom. Note the S-shaped handle originating after European silver-derived forms.

Snuff box, East London, England, ca. 1744. Porcelain. Diam. 2 5/16". (© National Museums and Galleries of Wales, De Winton Collection of Continental Porcelain, acc. no. D.W. 552.) Enameled with an incised “A” or “V.” A scene set within a scrolled cartouche is depicted on the lid. The body is decorated with various flowers and leaves associated with intertwined scrolls.

Hexagonal teapot, East London, England, ca. 1744. Porcelain. H. 3 1/8". (Private collection.) Enameled in the Kakiemon style with an incised “A,” this teapot has a replacement silver spout. The palette shows many similarities to the covered bowl and comprises iron red, bluish green, vibrant mid-blue, bright yellow, and mauve. Note that much of the design was initially outlined in thin black and subsequently filled in.

Hexagonal teapot and cover, East London, England, ca. 1743. Porcelain. H. 4 1/16". (Courtesy, © Copyright British Museum.) Both the base of the pot and the inside of the cover are marked with “A” in underglaze blue; the pot is enameled with molded shoulder decoration. The form of this teapot, together with its lion finial, suggest derivation from an unglazed stoneware or a salt-glazed prototype, possibly from Staffordshire or even South London.

Cricket, the quintessential English pastime, is in this account the link that brings together such seemingly disparate elements as a porcelain covered sugar bowl in the collection of the museum of the Melbourne Cricket Club (MCC), Cherokee clay obtained from North Carolina, the nascent English porcelain industry of 1743–1744, and colonial America’s fledgling ceramic tradition.

The MCC covered bowl belongs to a small body of porcelains called the “A-marked” group (figs. 1-6), owing to the presence of either an incised “A” or a painted “A” in underglaze blue. Thirty-six objects of this type have been recognized to date (figs. 7, 9-12).[1] The attribution and origin of the group, which appears to have been given its name by Arthur Lane,[2] have been the subject of considerable debate. Lane, Robert J. Charleston, and John V. G. Mallet have all outlined the main features of the A-marked group, examples of which occur either as polychrome or, uncommonly, in the white.[3] Lane noted that the porcelain body, having a modified chonchoidal fracture, was harder than what was typical of English porcelains, and he suggested that the body was of a hybrid type containing some kaolin clay. Mallet has divided A-marked porcelains into two broad groupings: the high style and stock pattern.

The MCC sugar bowl under discussion belongs to the high-style group. Four vignettes of extraordinary quality and technique are painted on the bowl and cover, one of which illustrates cricket being played—quite different from the modern version of the game but possibly not unfamiliar to some Australian cricketers. The game appears to have started in England and subsequently has spread to her various territories and dominions. Yet, strangely, cricket has not been taken up to any degree in continental Europe, and because of this, the cricket scene depicted on the cover of the bowl proved to be a crucial factor in ascribing an English origin for the A-marked porcelains. Arthur Lane had been inclined to a Continental origin; however, the discovery in 1961 of a partial tea set with the associated covered sugar bowl resulted in a general acceptance that A-marked wares were of British origin.[4] Subsequently, its factory source has been widely debated. Hilary Young notes that, “with the exception of a few individual items or small groups, among the earlier porcelains only the rare ‘A-marked’ wares still await an attribution.”[5] The quality of the potting, the porcelain body itself, and the startling enameling make this bowl the subject of considerable speculation.

With the discovery of high-fired porcelain by the Chinese in the T’ang period during the ninth century there developed a demand for such porcelaneous wares in Europe through trading and then for European production, initially in Florence under the patronage of Francesco de’ Medici. Florentine porcelain was an artificial glassy or frit porcelain, known generally as soft paste porcelain. Subsequent examples now recognized include pieces related to Padua (ca. 1627–1638), Rouen (ca. 1690), St. Cloud (ca. 1693), Chantilly (1730), and Vincennes (1740).[6] The first English attempts at porcelain appear to have been by John Dwight, commencing around 1671–1672; in North America, experimental firings were conducted by Andrew Duché in Savannah, Georgia, by May 1738[7]

In his paper dealing with the career of Andrew Duché, Graham Hood suggests that this potter, who was born in Philadelphia around 1710, could have been a pivotal figure in the most important period of the development of English and American ceramics. However, after discussing Duché’s career, Hood concludes that while Duché undoubtedly remains an important figure in the development of ceramics in America, his failure to improve his rudimentary porcelain appears to have discouraged him. There is no evidence that Duché ever had a significant connection with subsequent English or American porcelain factories, nor is there evidence that the American clay deposits were discovered primarily by Duché, or that such clay was ever used for other than experimental purposes.[8] Brad Rauschenberg expressed a comparable view when he stated that although Andrew Duché likely knew about the ingredients for porcelain and probably did discover kaolin in the New Windsor area, and perhaps in the southern Appalachians, he never produced porcelain wares himself.[9] Such conclusions were correctly and understandably predicated on the absence of any porcelain wasters or wares that could be reliably accredited to Duché.

A new development to this story emerged in 2001 with the publication of an article by W. Ross H. Ramsay, Anton Gabszewicz, and E. Gael Ramsay dealing with the ceramic patent taken out in England in 1744 by Edward Heylyn and Thomas Frye.[10] Heylyn and Frye are of particular interest to Americans because they were two of the proprietors responsible for the establishment of the Bow porcelain manufactory (New Canton) in Essex around 1749–1750. This concern gained wide recognition in its day, with many of its wares being exported to the New World. It is generally regarded as a prototype, both with respect to the recipe utilized and for much of the decoration used in America’s first porcelain manufactory, Bonnin and Morris in Philadelphia, which operated from 1770 to at least 1772.

The article on Heylyn and Frye’s 1744 ceramic patent identifies the type of clay referred to in the patent, locates its probable source (in the Little Tennessee River catchment, Macon County, North Carolina), and identifies the group of English porcelain wares most likely made by Heylyn and Frye using this Cherokee clay.[11] The authors proposed that such wares probably belong to the A-marked group of porcelains, to which the covered sugar bowl belongs. Moreover, the authors argued that there is now very strong circumstantial evidence linking this Cherokee clay, the Bow manufactory of Heylyn and Frye, and A-marked porcelain wares with the first-generation American-born potter Andrew Duché. They conclude their article by noting that,

If Andrew Duché did supply the raw clay as we suggest, then to what degree did he contribute to the Heylyn and Frye 1744 patent? It is unlikely that Duché supplied the clay without contributing in some way to the recipe from which the “A”-mark porcelain was manufactured. The intriguing unanswered question arises as to whether the results of Duché’s experimental porcelain efforts are to be found, not in Georgia, USA, but rather amongst the earliest recorded clay-rich porcelains of England.[12]

This paper reassesses these conclusions in light of new information, unavailable at the time to both Graham Hood and Brad Rauschenberg, and with regard to the polychrome porcelain covered sugar bowl in the collections of the MCC. In addition, the generally held view that the initial attempts at porcelain making in America were the result of both technological and artistic endowment from Europe—principally England—is revisited. On the basis of the chemical results obtained from the bowl, there are now reasonable grounds for arguing that the English porcelain tradition owes a great deal more to colonial American entrepreneurial enterprise, raw materials, and technology than has been recognized to date.

The Melbourne Cricket Club Museum came into existence in the Australian summer of 1968–1969 to house an outstanding gift by a young English stockbroker named Anthony Baer. His gift comprised over twelve hundred items pertaining to the game of cricket, including artwork, prints, books, manuscripts, bronzes, silverware, textiles, and porcelain. This gift introduced to Australia one of the most extensive, intriguing, and valuable collections of cricketana known, with items dating from the early seventeenth to the mid-twentieth century.

Anthony Baer began collecting cricket-related items in London during his school years, and by the early 1960s his collection had outgrown his London apartment. The extent of this collection reflects not only Baer’s interest but also his rapport with London’s art and antique dealers, who notified him of any items of significance that appeared on the market. In the early 1960s Anthony Baer visited the MCC to watch an English-Australian Test cricket match. Such was his regard for the hospitality extended to visitors at the ground and for the prowess of the Australian cricketers that within two years of the Test match he offered his collection as an immediate gift to the MCC.

In 1961 at the Antique Dealers Fair in London a partial tea set from the P. and K. Embden collection was put up for sale.[13] The pieces included a teapot, cream jug, sugar bowl with cover, and three saucers. Anthony Baer acquired all but two of the saucers. The sugar bowl went to the MCC, and the remainder went to the Victoria and Albert Museum.

The cover and bowl (fig. 1) trace their form back to Chinese examples.[14] The cover and bowl are each decorated with two vignettes surrounded by a rococo frame in distinct rouge de fer. In a detailed discussion on the source of the decoration, Charleston and Mallet were able to show that all four scenes could be traced back to a series of engravings detailing children’s pastimes that were printed and sold by James Cole. In the first set of engravings, inscribed, “The Second Part of Youthful Diverfions . . . Published According to Act of Parliament 7th May 1739 & Sold by J. Cole Engraver in Great Kirby Street, Hatton Garden,” Charleston and Mallet were able to identify three of the scenes—two on the bowl (Swinging on the Rope [fig. 2] and Youth Sliding on the Ice [fig. 3]) and one on the cover (Youth Playing at Cricket [fig. 4]).[15]

The fourth scene, Throwing at Cocks (fig. 5), which appears on the cover of the bowl, shows a group of children with a cock tied by its leg. Charleston and Mallet have traced this scene to an engraving in another series of children’s pursuits inscribed “Published According to an Act of Parliament of October 24th, 1740 by James Cole, engraver at ye Crown in Great Kirby Street Hatton Garden.” Charleston and Mallet were able to trace these scenes to a further group of prints titled Jeux, part of a series called Petits cahiers d’images pour les enfants, now in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris. They deduced that the author was Hubert-François Bourguignon, called Gravelot (1699–1773), who was in London probably from 1732 or 1733 until 1745, when he returned to France. Gravelot, a former pupil of the history painter Jean Restout II and a student in the studio of François Boucher in 1732, was a highly talented engraver, painter, and designer. He is regarded as having had a significant influence on English illustration and is believed to have supplied various illustrations to English publishers.

The scene showing the cricket game (fig. 4) is found reversed in Le Jeu de la Crosse, an engraving signed “Gravelot inv.” and “Bachelet sculps.” Charleston and Mallet suggest that Le Jeu de la Crosse was created in England about 1739 (presumably by Gravelot while he was associated with the St. Martin’s Lane Academy) and then reproduced in the reverse after his return to France. In view of the deduced association between Gravelot’s drawings and the decoration on the covered bowl, it might appear that there was indeed some verisimilitude in the prophetic comments by the engraver George Vertue that Gravelot would “furnish this Nation with many things . . . of a much better taste.”[16] The shop of the engraver John Boydell, whose sign was that of a cricket bat, was apparently located near the academy, in Duke’s Court, St. Martin’s Lane.[17]

The identity of the artist who painted the on-glaze enamel scenes on the bowl and cover has been the subject of debate. Bouwman speculates that the scenes could be the work of Francis Hayman, who knew Gravelot and was himself a lover of cricket and a member of the St. Martin’s Lane Academy.[18] Moreover, he is generally regarded as a pioneer of the application of the French rococo art style into the English idiom. Errol Manners comments:

Whilst I cannot point out a stylistic link, it is apparent that the quality of painting is so unusually high and ambitious for English porcelain that it was clearly done by no ordinary china decorator, but by an accomplished artist. Frye being versatile enough to work as an oil painter, a miniaturist, and a mezzotint artist would have found it difficult to resist applying his talents to such a novel and exciting medium. Furthermore he was the only one of the partners who was an artist and both his daughters became painters at Bow and both married china painters. It is interesting to read the entry on the Melbourne Cricket Club “A”-marked bowl in the catalogue “Glorious Innings, Treasures from the Melbourne Cricket Club,” by Richard Bouwman, p. 13, where they discuss that the style of painting is typical of an oil painter and they suggest Francis Hayman as the possible artist because he knew Gravelot, from whose print the design [on the bowl] was taken. However Bow also used Gravelot prints and as Frye would have mixed in the same circle, that argument could equally have applied to Frye. This line of argument finds some modest support in Frye’s epitaph published in the Gentleman’s Magazine, 1764, where it states of Frye that, “He spent fifteen years among the furnaces till his health was nearly destroyed,” so we know that he was a “hands on” manager.[19]

Both the cover and bowl have a warm, creamy, gray-white color with a thin, tight-fitting, clear glaze that shows minimal evidence of running or pooling. The glaze has a very fine, “orange skin” texture. Present are blemishes and pits evidenced by fine black to brownish spots. These blemishes most likely relate to remnant biotite or breakdown products, such as hydromica and chlorite, derived from precursor garnet as recorded in unaker, or china clay from Macon County, North Carolina.[20]

Underglaze tears are present in the body, especially on the lid. Judging by the light postglaze grinding of the footrim and the outer margin of the lid, the bowl and lid were fired upright. Both the footrim and the inverted footrim have been lightly faceted or ground; the latter, however, was ground prior to the application of the glaze. The palette comprises an iron red, brown grading into black, purple, blue-green, blue, and yellow. Admixtures of these colors have yielded additional hues, including flesh pink, pinkish orange, turquoise green, and varying shades of yellow resulting from a thickly applied to a thin yellow wash. This latter color, along with the green, appears to have been among those applied last. The blue appears to have taken well where applied directly on the glaze, but has bubbled and blistered where painted over the brown. The background foliage in brown, brownish black, and green, or russet brown and green, is delicately painted with texture that was applied through subsequent fine scratching of the enamel in hook-shaped or wavy patterns. A remarkable ghosting technique on some of the background foliage has given a good sense of depth. In Swinging on the Rope (see fig. 2) a light green wash was applied over a portion of the sgraffitoed tree foliage. Translucency is a grayish white; contraction of the body during firing resulted in a poorly fitting lid. The base of the bowl contains the letter A, which was quickly drawn using three brush strokes in underglaze blue. This letter, which gives the group its name, shows little resemblance to the “Argyll A.”[21]

The factory source has been ascribed to continental Europe by Lane; to Vauxhall or Gorgie out of Edinburgh by Charleston and Mallet; to Kentish Town, Stourbridge, or Gorgie by Mallet; and to Scotland, Chelsea, or Italy by John and Margaret Cushion.[22] Ian Freestone, while noting the strong correspondence between determined A-marked compositions and the recipe contained in the 1744 Heylyn and Frye ceramic patent, appears to have favored a Pomona or Limehouse attribution.[23] Subsequently he noted that the relationship between A-marked wares and other products of the mid-eighteenth century remains unclear, although he recognized the distinct possibility that the A-marked porcelain utilized an imported North American clay as specified by Heylyn and Frye’s 1744 patent.[24] More recently, Ramsay, Gabszewicz, and Ramsay suggested that this group of porcelains in fact represents the “long lost” representatives of the patent.[25]

Chemical Analysis of Body and Glaze

A small amount of the clear, thin, tight-fitting glaze and the underlying porcelain body were lightly abraded from the inside of the basal footrim of the MCC bowl using a portable high-speed dental drill with drill bits tipped with diamonds set in a stainless steel matrix. Approximately 0.4 mg of ceramic powder and 0.2 mg of glaze were collected, mounted in epoxy resin, polished, and subjected to quantitative chemical analysis using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) with an energy dispersive attachment. Operating conditions are given in the Appendix. The chemical compositions so obtained for both body and glaze are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 presents two analyses of the covered bowl, one for the body and the other for the glaze. The analysis from the porcelain body compares with a previous analysis taken from the flange of the lid from a teapot in the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) that also belongs to the so-called high-style group.[26] Previous analyses of A-marked wares, both published and in preparation, have shown considerable variation in the glass-to-clay ratio and in the composition of the glass used. In this example, however, there is close chemical agreement with the V&A teapot.[27] Both examples demonstrate virtually identical SiO2-to-Al2O3ratios. Likewise there is reasonable agreement with regard to CaO, with the covered bowl having slightly higher amounts (7.3 wt %) than the teapot (5.9 wt %). K2O and MgO are both lower in the covered bowl, indicating some variability in the glass composition used. The similarity in chemical composition (and, hence, recipe) between the MCC covered bowl and the V&A teapot suggests that the paste composition had become more or less standardized in the production of these two representatives of the high style. This more uniform recipe with a closely comparable SiO2 : Al2O3 ratio ~ 2.2, together with the remarkable enameling, suggests that these examples were made using a higher proportion of scarce, imported clay, and probably were made toward the end of the A-marked porcelain output period, possibly dating from the mid- to latter half of 1744.

The chemical composition of the porcelain bowl strongly suggests that it is composed of a mixture of residual or primary kaolinite clay (as judged by the very low FeO and below-detection-level amounts of TiO2) and a calciferous alkali-glass. Such low levels of these elements are a feature of primary kaolinite or china clays, such as those found in the Franklin-Sylva district of North Carolina.[28] J. Victor Owen has noted that low to nonexistent levels of these two elements either indicates the presence of a well-washed and screened secondary clay or suggests that the clay used in the paste was initially relatively free of these impurities, as would be expected in a primary kaolinite clay.[29] One of the most common sources of ball clay for mid-eighteenth-century London and Staffordshire potters was the mid-Eocene Broadstone Sequence in the Wareham Basin, Dorset. Average analyses of this clay unit demonstrate TiO2 levels of 1.30 wt % and Fe2O3 of 1.30 wt %.[30] Judging by analyses of wares from other contemporaneous factories, there is no evidence that proprietors in England at that time had the ability to wash completely and remove these colorant oxides from the secondary clays used.[31] Consequently the clay used in the MCC sugar bowl—and in all other A-marked items analyzed to date—must have been a primary, residual kaolinite clay.[32] Mineralogical analysis of this clay from the most likely source mine (Iotla mine) in the Little Tennessee River catchment north of Franklin in Macon County, North Carolina, demonstrates that the clay comprises 90 percent halloysite and 10 percent kaolinite. This use of a primary residual kaolinite clay contrasts with most mid-eighteenth-century English porcelains, which comprise variable amounts of ball or pipe clay with distinctly higher levels of titanium and iron. The notable exception to this are the hard paste porcelains made by Richard Champion and William Cookworthy (Plymouth and Bristol) dating from the mid- to late 1760s onward.

The calculated recipe used for the MCC sugar bowl is given in Table 2; the clay:glass ratio is approximately 60 percent clay (hydrous) to 40 percent glass. These features—the high clay content, the deduced use of a primary kaolinite clay, the use of a lead-free alkali-lime glass frit, the typical absence of remnant ground-quartz or flint particles, and the composition of the glaze containing a clay component and lacking PbO—confirm that the bowl belongs to the A-marked group of porcelains, as initially proposed by Charleston and Mallet.[33] Moreover, the body and glaze compositions closely reflect the chemical compositions as reconstructed from the 1744 patent.[34]

The high aluminum content in the body of the MCC bowl (27.7 wt % Al2O3) indicates that the recipe used was a high-clay-content recipe, a feature reflected in the products from three factories operating at that time—namely Pomona or Newcastle-under-Lyme, Limehouse, and the maker of the A-marked wares.[35] Ian Freestone and Ramsay et al. have discussed the key chemical features that distinguish A-marked porcelains from Pomona and Limehouse wares.[36]

The glaze analysis indicates a composition more siliceous and less clay-rich than the body, comparable to other glaze compositions obtained from A-marked wares in that it is lead-free and highly calciferous with a distinct clay component, as deduced from the Al2O3 levels in the glaze. This glaze composition appears to be unique for mid-eighteenth-century English porcelains and conforms to the expected composition, as deduced from the glaze recipe contained in the 1744 patent.[37]

From the above it is reasonable to conclude that the kaolinite clay used in both the body and glaze was most likely derived from North America as specified in the 1744 patent. The source was possibly the Iotla mine or the Guerny mine, some five miles north of Franklin.[38] Other potential sources of such primary kaolinite clay include Cornwall, the Bohemian Massif, and China. There is no apparent evidence of Chinese or Eastern European primary kaolinite clay being imported into England at this time. Although William Cookworthy might have been aware of the kaolinite deposits at Tregonning Hill in Cornwall by about 1745–1746, there is no indication that porcelains were being made using Cornish kaolinite until the mid- to late 1760s, when Cookworthy took out a patent (1768).[39]

Conclusions

A series of landmark papers and an authoritative book on the Bow factory and its products have significantly influenced our current understanding of the Bow porcelain manufactory and the proprietors who managed and financed the concern.[40] In his 1963 paper Hugh Tait made the following points:

• Andrew Duché found clay “somewhere in the remote hinterland in the territory of the Chirokee Indians”;

• this clay was the essential ingredient for making porcelain;

• Duché made porcelain using that clay;

• Duché brought both clay and porcelain to London;

• the granting of the Heylyn-Frye patent coincided with Duché’s arrival in London;

• Duché returned to America to dig clay; and

• Frye was a painter who was attracted to porcelain making.

Tait concluded that the two driving forces behind the Bow manufactory were Thomas Frye and George Arnold: Frye was the genius who discovered the secret to making porcelain, and Arnold was the businessman whose financial backing and faith in Frye made this pioneering venture possible. Tait also stated that the Bow manufactory was far more British, far more free from foreign influences and dominance, than either Chelsea or Derby.[41] These views were based largely on the fact that the 1744 patent was applied for by, and granted to, Heylyn and Frye, as well as on the wording in Frye’s epitaph, published in Gentleman’s Magazine in 1764, which stated that Thomas Frye was the inventor and first manufacturer of porcelain in England.[42]

The weakness in this series of proposals is that while Frye was actively involved in painting and mezzotint engravings on one side of the Atlantic Ocean during the late 1730s and early 1740s, on the other side of the Atlantic, Duché was experimenting with the secrets of making porcelain. In fact, there is reasonable evidence that he was experimenting with unaker clay, the very clay deduced to have been used in the manufacture of A-marked porcelains by May 1741.[43] Frye in effect attested to this himself, when in his 1744 patent he listed his profession not as “ceramic experimentalist” or “potter” but as “painter.” Tait acknowledged this weakness by admitting that it was not known why Frye was attracted to porcelain making.[44] Frank Hurlbutt also commented on this problem, suggesting, “It may have been due to his helping Brooks [an Irish colleague] in his experiments in printing on enamel and porcelain that Thomas Frye was first led to experiment with bodies and glazes for making porcelain itself.”[45]

Based on a study of the MCC’s A-marked covered bowl, our conclusion is that the bowl is made of a mixture of kaolinite clay and lime alkali-glass in the general proportions of 60 percent clay (hydrous) to 40 percent glass by weight, a recipe unique to A-marked porcelains, and conforms to the reconstructed 1744 patent of Heylyn and Frye[46]

We suggest that the most reasonable deduction is that the kaolinite group clay utilized was sourced from the Cherokee Nation, as stated in the 1744 patent. Moreover, we support previous suggestions that the most likely supplier of this remarkably white clay mixture was Andrew Duché himself. We cannot accept the long-held notion that Duché supplied this clay to the Bow proprietors, provided examples of his experimental porcellaneous wares, and then passively returned to America to continue digging clay, thus allowing Thomas Frye to discover the secret of porcelain making.

While not in any way diminishing Thomas Frye’s qualities of skill, energy, and imagination in developing the large-scale success of the Bow manufactory, we suggest that for too long several aspects have been ignored or overlooked: the vital contribution from colonial America in the form of the raw clay; the recognition of its ceramic potential; the entrepreneurial enterprise associated with the transportation of that clay to London; and almost certainly a significant component of the associated technology required to make porcelain. While we accept that Duché would have been influenced by Chinese and early European porcelain examples obtained through imports and supplied to him by the Countess of Egmont, his recognition of the ceramic potential of Cherokee clay, his initial transportation of samples of that clay (most likely down the Savannah River), and his experimental firings in Savannah were done largely in isolation.

We suggest that Andrew Duché acted as a vital catalyst in attracting Arnold and Heylyn to develop what we now believe to be England’s earliest quality porcelains, the A-marked wares.[47] We contend that Alderman George Arnold’s faith in apparently investing financially in this early venture was based not so much on Frye’s undoubted ability to paint but rather on Andrew Duché’s entrepreneurial ability, his stunning white clay, his porcellaneous samples (which we accept he brought to England with him), and his knowledge of firing porcellaneous wares gained during his time in Savannah. We accept that the potting of the MCC bowl and the remarkable enameling on it were almost certainly of English derivation.

Likewise, the general impression one gains from the current literature is that early porcelain production in America is viewed as largely the result of an Asiatic-European endowment in the form of technology and artistic conception.[48] Hood and Adams and Redstone have commented on the influence of the European tradition and the Bow factory on initial porcelain manufacture in the American colonies.[49] Possibly the best summary of current thinking has been expressed by Terrence Lockett:

The principal reason for such an extensive trade was the lack of any indigenous American fine earthenware (or porcelain) industry before the Revolution. There were potters in America, but on the whole with the exceptions of Bartlem in South Carolina and Bonnin and Morris in Philadelphia, only relatively coarse wares for local consumption were produced.[50]

In one sense we agree with Lockett in that Duché chose to develop and promote his white unaker clay and his technology in London, not in America. Yet some twenty-five years prior to the establishment of Bonnin and Morris (American China Factory), we would suggest that it was the Bow manufactory in East London and its proprietors who were indebted to the raw materials, to the considerable enterprise, and possibly to some technology transfer from America. It was this ceramic tradition, developed initially in Philadelphia by potters such as Anthony Duché and then in Savannah, Georgia, by his son, that was to play such an important role in the initial porcelain production of the Heylyn and Frye manufactory. These A-marked wares, most likely containing Cherokee clay, appear to be the earliest quality porcelains to have been made in Britain, dating from at least 1743, according to current evidence. This ceramic concern subsequently grew into the specially built manufactory (New Canton), which in turn greatly influenced Bonnin and Morris in Philadelphia a quarter of a century later. While ceramic historians have emphasized the influence that Bow and the European tradition had on Bonnin and Morris, little attention has been afforded the “Philadelphia ceramic tradition” and its prior influence on English porcelains.

In summary we note, with regard to Graham Hood’s article on the career of Andrew Duché,[51] that Andrew Duché is in fact a pivotal figure in English and American ceramics, and that the contribution by colonial America to the fledgling English porcelain and subsequent bone china industry needs to be reevaluated. We suggest that Duché did make experimental wares of a porcellaneous nature in Savannah of sufficient quality that, together with his remarkably white clay, attracted the attention of Arnold and Heylyn. The identification of A-marked porcelains—with their assumed content of Cherokee clay or unaker—as the likely “long-lost” representatives of the 1744 Heylyn and Frye patent now constitutes very good circumstantial evidence that Andrew Duché had a significant if not seminal connection with both the Bow manufactory and its proprietors. While the initial European discovery of the Cherokee clay deposits was probably by metalliferous prospectors en route through the Iotla Valley and over the Nantahala Ranges to the Nantahala Valley in western North Carolina, it was Duché who recognized the ceramic potential of these residual clays and it was he who was actively experimenting with this clay by mid-1741. There is now very reasonable evidence that this clay, “the produce of the Chirokee nation,” was being used in the limited commercial—not experimental—production of highly sophisticated porcelains in East London by at least 1743 or 1744. Such developments owed a great deal to American enterprise, which to date has been largely overlooked.[52]

Future lines of research include the identification of the initial kiln site, assumed to have been located in East London, and the possible recovery of A-marked wasters. An important question yet to be addressed is whether Andrew Duché made contact with Arnold and Heylyn prior to embarkation for London in 1743 or whether, on hearing rumors of Duché’s experimental porcelain firings in Savannah, they sought him out first. We note that the genius—if that is the correct word—required to discover the secret to making porcelain might lie more with Andrew Duché than with Thomas Frye. If wasters of A-marked porcelain are ever uncovered on which multi-element chemical analysis can be conducted, thus allowing conclusive sourcing of the primary clay used in the porcelain body to North Carolina, then we suggest that there would be a basis for proposing that Andrew Duché, a first-generation Philadelphian, be recognized as one of the founding fathers of the English and American porcelain industry.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for travel to North Carolina to collect samples was made to the senior author by the Research Office, Deakin University, and by Professor N. W. Archbold from research funding to the interim Priority Research Area, Global Change, Deakin University. Both contributions were invaluable and we offer our sincere thanks. Jo Ann and Frank Meeks of “The Centre,” Rose Creek, North Carolina, and Gloria Durfey contributed greatly to the visit to North Carolina by providing accommodation, information, and trips to see the local geology. Robert Douglas, Monash University, provided expert polished specimen preparation, Steve Swenser undertook the SEM analyses, and Erin O’Brien kindly carried out the photography. John Mallet, Anton Gabszewicz, and Barry Taylor provided helpful comments and advice and were always willing to share their knowledge and collections. Special acknowledgment is made of Gillian Brewster, manager, Museums Department, Melbourne Cricket Club, who gave permission to sample and photograph the covered bowl. Three internal reviewers, Maurice Hillis, Errol Manners, and an anonymous reviewer, kindly commented on a draft version of the manuscript and offered valuable advice.

Interested readers may contact the authors through Gael Ramsay at <gaelramsay@ballarat.vic.gov.au>.

This paper is dedicated to David C. D. Cooke, formerly of 99 Shortland Street, who first kindled an interest in antiques in the senior author.

Samples of abraded ceramic powder and glaze were mounted in PVC, polished, and subjected to chemical analysis using a JEOL 840A scanning electron microscope (SEM) equipped with an Oxford Instruments ATW X-Ray Energy Dispersive Spectrometer (XEDS). Each sample was coated with a film of amorphous carbon (<3nm) to prevent charge buildup. Each spectrum was counted for 120 seconds with the microscope at high-tension at 40 kV, the probe current set at 6nA, and a nominal working distance of 39nm. Internal standards were employed and accuracy was ± 5 percent. For areal analyses, spectra were acquired while the beam was set to raster slowly over square areas 2.3 x 2.3 mm. Glaze analyses were by spot analysis. Results were expressed as oxide percents with O by difference.

| Table 1: Chemical Analysis (wt %) for Body and Glaze Composition | ||||

Body of MCC bowl |

V&A teapot |

Glaze composition of MCC bowl |

Calculated

glass frit composition (MCC bowl body) |

|

| SiO2 | 59.7 |

59.5 |

74.4 |

68.3 |

| TiO2 | bdl |

na |

bdl |

|

| Al2O3 | 27.7 |

26.4 |

8.3 |

|

| P2O5 | bdl |

na |

bdl |

|

| FeO | 0.1 |

na |

0.4 |

|

| MgO | 0.3 |

1.2 |

1.5 |

0.8 |

| CaO | 7.3 |

5.8 |

10.7 |

18.5 |

| Na2O | 3.7 |

3.8 |

2.2 |

9.4 |

| K2O | 1.2 |

2.8 |

2.5 |

3.0 |

| PbO | bdl |

na |

bdl |

|

| Total | 100.0 |

99.5 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

| bdl = below detection level | ||||

| na = not analyzed | ||||

| Table 2: Theoretical Paste Recipe Used in Producing the MCC Bowl* | |

|

weight % (hydrous)

|

|

| Kaolinite (unaker clay) |

59.0

|

| Soda ash |

5.3

|

| Potash |

1.5

|

| Limestone |

10.3

|

| Dolomite** |

1.2

|

| Quartz / flint*** |

22.7

|

* Method calculates volatiles (CO2 and H2O) and recasts to 100 percent; after J. Victor Owen, “Antique Porcelain 101: A Primer on the Chemical Analysis and Interpretation of Eighteenth-Century British Wares,” Ceramics in America, edited by Rob Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2002): 39–61.

** Although dolomite is suggested as the source of MgO, various vegetable ashes of the day could have been the source for magnesium.

*** This quartz and/or flint would have been incorporated in the glass frit used and would not have been a separate phase.

On October 9, 2002, an unrecorded fluted cup—closely comparable to figure 1 in W.R.H. Ramsay, Anton Gabszewicz, and E. G. Ramsay, “The Chemistry of ‘A’-Marked Porcelain and Its Relation to the Heylyn and Frye Patent of 1744,” Transactions of the English Ceramic Circle 18, pt. 2 (2003): 264–83—but more densely enameled and with a brown painted rim, was auctioned by Dreweatt Neate, Newbury, lot 376. See also J.V.G. Mallet, “The ‘A’ Marked Porcelains Revisited,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 15 (1994): 240–57.

Arthur Lane, “Unidentified Italian or English Porcelains: The A Marked Group,” Mitteilungsblatt (Keramik-Freunde der Schweiz ), no. 43 (1958): 25.

Lane, “Unidentified Italian or English Porcelains,” pp. 15–18; Robert J. Charleston and J.V.G. Mallet, “A Problematical Group of Eighteenth-Century Porcelains,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 8, pt. 1 (1971): 80–121; Mallet, “‘A’ Marked Porcelains Revisited,” pp. 240–57.

Lane, “Unidentified Italian or English Porcelains”; Charleston and Mallet, “Problematical Group of Eighteenth-Century Porcelains”; Mallet, “‘A’ Marked Porcelains Revisited.”

Hilary Young, English Porcelain 1745–95: Its Makers, Design, Marketing and Consumption, Victoria and Albert Museum Studies in the History of Art and Design (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1999), p. 229.

Maurice Hillis, “An Introduction to Ceramic Raw Materials, Bodies and Glazes,” Journal of the Northern Ceramic Society 18 (2001): 77–111.

B. L. Rauschenberg, “Andrew Duché: A Potter ‘A Little Too Much Addicted to Politicks,’” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 7, no. 1 (1991): 1–101.

Graham Hood, “The Career of Andrew Duché,” Art Quarterly 31 (1968): 168–84.

Rauschenberg, “Andrew Duché.”

W.R.H. Ramsay, Anton Gabszewicz, and E. G. Ramsay, “‘Unaker’ or Cherokee Clay and Its Relationship to the ‘Bow’ Porcelain Manufactory,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 17, pt. 3 (2001): 473–99.

Ibid.

Ibid., p. 492.

Richard Bouwman, Glorious Innings: Treasures from the Melbourne Cricket Club Collection (Melbourne: Hutchinson Australia, 1987), p. 131.

For example, see the Ch’ien Lung famille rose bowl and cover from The Metropolitan Museum of Art illustrated in Warren E. Cox, The Book of Pottery and Porcelain (New York: Crown Publishers, 1970), 2: 1158, and a Ch’ing dynasty bowl and cover illustrated in W.B.R. Neave-Hill, Chinese Ceramics (Edinburgh and London: John Bartholomew and Sons, 1975), p. 176.

Charleston and Mallet, “Problematical Group of Eighteenth-Century Porcelains,” pp. 80–121.

Quoted in William Vaughan, Gainsborough (London: Thames and Hudson, 2002), p. 224.

Robin Simon and Alistar Smart, The Art of Cricket (London: Secker and Warburg, 1983).

Bouwman, Glorious Innings, p. 131.

Errol Manners, personal communication, May 2002.

W. S. Bayley, “The Kaolins of North Carolina,” North Carolina Geological and Economic Survey, Bulletin 29 (1925): 132.

Nancy Valpy, “‘A’-Marked Porcelain: ‘A’ for Argyll?,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 13, pt. 1 (1987): 96–107.

John P. Cushion and Margaret Cushion, A Collector’s History of British Porcelain (Woodbridge, Suffolk, Eng.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1992), p. 448.

Ian C. Freestone, “A-Marked Porcelain: Some Recent Scientific Work,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 16, pt. 1 (1996): 76–84.

Ian C. Freestone, “The Science of Early English Porcelain,” in The Sixth Conference and Exhibition of the European Ceramic Society, 20–24 June 1999, Brighton Conference Centre, UK: Abstracts; British Ceramic Proceedings, no. 60 (London: IOM Communications, 1999), 1: 11–17; Ian C. Freestone, “The Mineralogy and Chemistry of Early British Porcelain,” Mineralogical Society Bulletin (July 1999): 3–7.

Ramsay, Gabszewicz, and Ramsay, “‘Unaker’ or Cherokee Clay”; Ramsay, Gabszewicz, and Ramsay, “Chemistry of ‘A’-Marked Porcelain.”

Mavis Bimson and Michael J. Hughes in Charleston and Mallet, “Problematical Group of Eighteenth-Century Porcelains,” pp. 80–121. The teapot and cover (V&A C.207 and A-1937) are illustrated in ibid., pl. 65b.

Bimson and Hughes in Charleston and Mallet, “Problematical Group of Eighteenth-Century Porcelains”; Freestone, “A-Marked Porcelain”; Ramsay, Gabszewicz, and Ramsay, “Chemistry of ‘A’-Marked Porcelain.”

Freestone, “A-Marked Porcelain”; Ramsay, Gabszewicz, and Ramsay, “‘Unaker’ or Cherokee Clay.”

J. Victor Owen, “Geochemical and Mineralogical Distinctions between Bonnin and Morris (Philadelphia, 1770–1772) Porcelain and Some Contemporary British Phosphatic Wares,” Geoarchaeology 16, no. 7 (2001): 785–802.

Andrew Deeming, personal communication, January 2003.

Ramsay, Gabszewicz, and Ramsay, “Chemistry of ‘A’-Marked Porcelain”; Freestone, “A-Marked Porcelain.”

Freestone, “A-Marked Porcelain”; Ramsay, Gabszewicz, and Ramsay, “Chemistry of ‘A’-Marked Porcelain”; W.R.H. Ramsay, G. Hill, and E. G. Ramsay, “Re-creation of the 1744 Heylyn and Frye Ceramic Patent Wares Using Cherokee Clay: Implications for Raw Materials, Kiln Conditions, and the Earliest English Porcelain Production,” Geoarchaeology, in press.

Ramsay, Gabszewicz, and Ramsay, “Chemistry of ‘A’-Marked Porcelain”; Charleston and Mallet, “Problematical Group of Eighteenth-Century Porcelains.”

Ramsay, Gabszewicz, and Ramsay, “‘Unaker’ or Cherokee Clay”; Ramsay, Gabszewicz, and Ramsay, “Chemistry of ‘A’-Marked Porcelain.”

Freestone, “Science of Early English Porcelain,” and Freestone, “Mineralogy and Chemistry of Early British Porcelain.”

Freestone, “A-Marked Porcelain”; Ramsay, Gabszewicz, and Ramsay, “Chemistry of ‘A’-Marked Porcelain.”

Ramsay, Gabszewicz, and Ramsay, “Chemistry of ‘A’-Marked Porcelain.”

Ramsay, Gabszewicz, and Ramsay, “‘Unaker’ or Cherokee Clay.”

Bernard Watney, English Blue and White Porcelain of the 18th Century (London: Faber and Faber, 1973), p. 145; Hillis, “Introduction to Ceramic Raw Materials, Bodies and Glazes,” pp. 77–111.

Hugh Tait, Bow Porcelain, 1744–1776: A Special Exhibition of Documentary Material to Commemorate the Bi-centenary of the Retirement of Thomas Frye, Manager of the Factory and “inventor and first manufacturer of porcelain in England,” exh. cat., British Museum, London, October 1959–April 1960 (London: Trustees of the British Museum, 1959); Hugh Tait, “The Bow Factory under Alderman Arnold and Thomas Frye (1747–1759),” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 5, pt. 4 (1963): 195–216; Hugh Tait, “Bow,” in English Porcelain, 1745–1850, edited by R. J. Charleston (London: E. Benn, 1965), pp. 42–52; Elizabeth Adams and David Redstone, Bow Porcelain (London: Faber and Faber, 1981), p. 251.

See Tait, Bow Porcelain, 1744–1776, fig. 1, and Tait, “Bow Factory under Alderman Arnold and Thomas Frye,” p. 195.

The epitaph is quoted in full in Adams and Redstone, Bow Porcelain.

Ramsay, Gabszewicz, and Ramsay, “‘Unaker’ or Cherokee Clay.”

Tait, “Bow Factory under Alderman and Thomas Frye.”

Frank Hurlbutt, Bow Porcelain (London: G. Bell and Sons, 1926).

Ramsay, Gabszewicz, and Ramsay, “Chemistry of ‘A’-Marked Porcelain.”

See Tait, “Bow,” p. 43.

Graham Hood, Bonnin and Morris of Philadelphia: The First American Porcelain Factory, 1770–1772 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1972); Garrison Stradling, “American Ceramics and the Philadelphia Centennial,” Antiques 110 (July 1976), pp. 146–58; Graham Hood, “The American China,” in The American Craftsman and the European Tradition, 1620–1820, edited by Francis J. Puig and Michael Conforti (Minneapolis: Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 1989), pp. 240–55; Garrison Stradling, “American Porcelains,” in Sotheby’s Concise Encyclopedia of Porcelain, edited by David Battie (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1990), pp. 182–83; Morrison H. Heckscher and Leslie Greene Bowman, American Rococo, 1750–1775: Elegance in Ornament, exh. cat., Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, January 26– May 17, 1992; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, July 5–September 27, 1992 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992), p. 288.

Hood, Bonnin and Morris of Philadelphia; Adams and Redstone, Bow Porcelain.

Terrance Lockett, “English Porcelain and Colonial America,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 16, pt. 3 (1998): 283–97.

Hood, “Career of Andrew Duché.”

Tait, Bow Porcelain, 1744–1776; Watney, English Blue and White Porcelain.