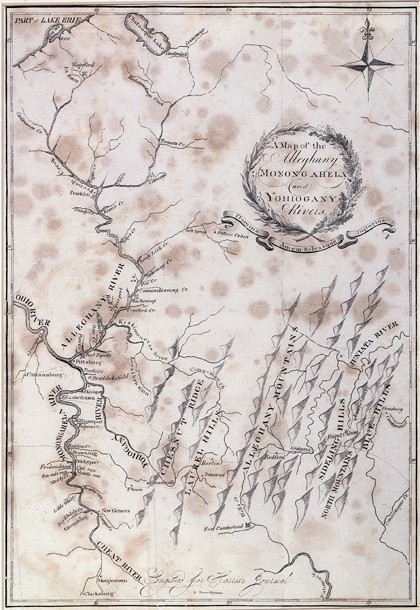

Thomas Wightman, “A Map of the Alleghany, Monongahela and Yohiogany Rivers,” 1805. This map is from the Journal of a Tour in the Territory Northwest of the Alleghany Mountains Made in the Spring of the Year 1803 by Thaddeus Mason Harris. It shows the Monongahela Valley, Clarksburg, Morgantown, Greensboro, New Geneva, and Pittsburgh. (Duez Collection.)

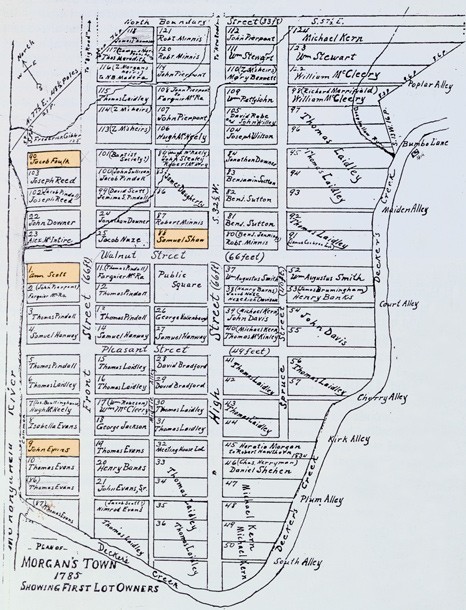

James M. Callahan, History of the Making of Morgantown, West Virginia (Morgantown: West Virginia University Studies in History, 1926). Reconstructed by county clerk Evans after loss of the court records in a 1796 fire.

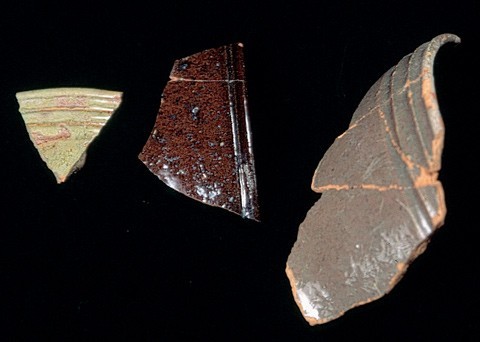

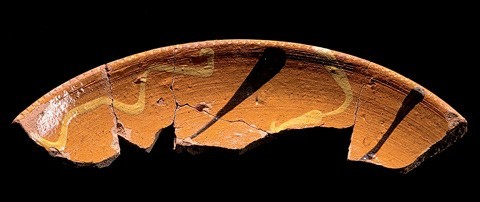

Sherds, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1810. Earthenware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These fragments were recovered from the basement of the Old Stone House in Morgantown. (The town was still part of Virginia at the time they were made, as West Virginia did not become a state until 1863.) The very thin walls, which are approximately 1/8 " thick, may be evidence of the production of “fine” tablewares during the Jefferson Embargo period. Several sherds with piercing (not shown) also suggest attempts at producing fine tablewares.

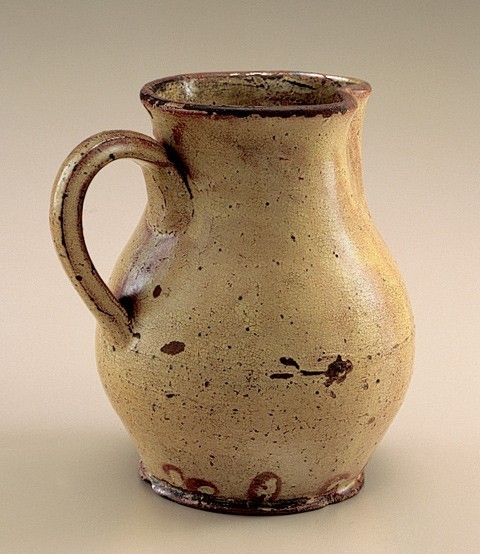

Pitcher, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1810. Earthenware. H. 7 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This straw-colored pitcher is finely formed and finished, and although it is not thin-walled it may be what Hough called “yellow tableware” of the Jefferson Embargo period. Its handle has the chamfered-edge cross section noted under jugs. The pitcher has a capacity slightly less than one quart. It was found in a Morgantown yard sale.

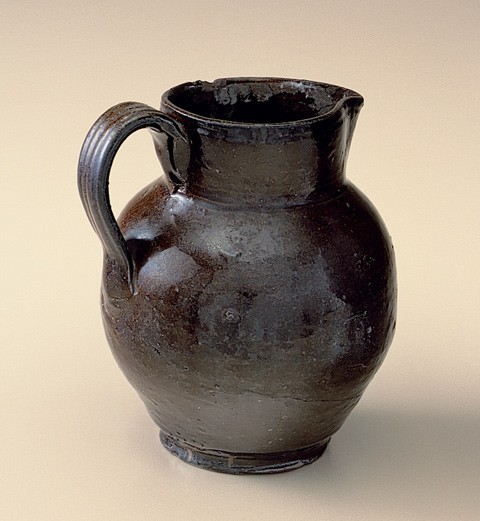

Jug, probably Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1810. Earthenware. H. 8 5/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

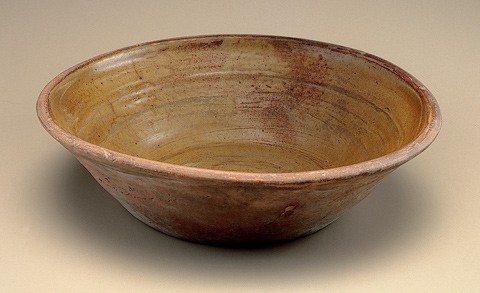

Milk pan, probably Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1830. Earthenware. D. 14 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Old Stone House, Morgantown, West Virginia. (Photo, Richard Duez.) This building, on the north half of Lot 25, was owned by Jacob Foulk Jr. from 1807 to 1809, when it passed to James Goff, who then sold it to John W. Thompson in August 1810. Thompson kept it until May 1813. The earthenware floor of the basement contained several wheelbarrow loads of clay—more orange clay than white clay—and some earthenware sherds. A stone-lined drain capped with stone ran from the front to the back. It is now the home of the Morgantown Service League and is on the National Register of Historic Places.

The kiln used jointly by Jacob Foulk Jr. and John W. Thompson. (Photo, Don Horvath.) Located on Lot 88, the kiln operated from about 1812 to 1830. It was uncovered in 1992, when a later structure built over it was partially burned and subsequently removed. When first seen, there were several courses of dense, dark-red bricks atop a sandstone foundation approximately 1 foot thick and 3 1/2 feet above a consolidated floor. The stones were irregular and there was little or no mortar bonding them.

The west end of the chamber was a somewhat flattened half circle with an inner radius of approximately 2 feet. This merged with two parallel sides 5 feet apart running about 6 or 8 feet to the east wall. The latter had an opening about 3 feet wide from which two parallel walls extended a short distance farther east. At the time of the photo the eastern end was already reburied, in preparation for paving a parking lot that same day. Note the remnants of red bricks in the center foreground. There were considerable accumulations of unfired, mostly orange, clay containing some sherds close to the mouth of the kiln.

Sherds, attributed to Jacob Foulk, Morgantown, West Virginia, 1812–1830. Slipware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These fragments were recovered from the site immediately east of the kiln illustrated in fig. 8. The attribution to Jacob Foulk is based in part on similar sherds found in Shepherdstown where he may have trained before going to Morgantown. Note the viscous dark slip stems in relief and the deft brushstrokes.

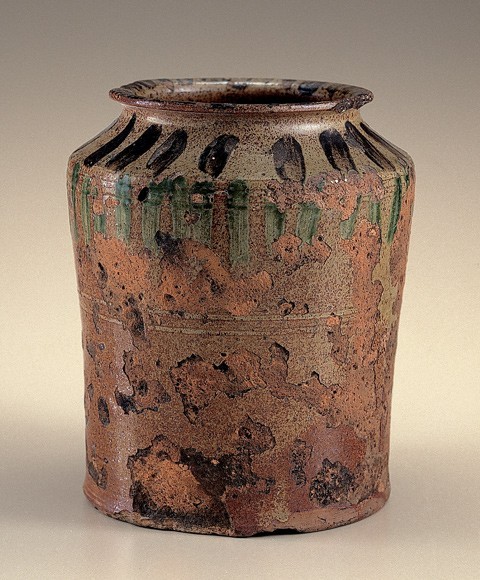

Jar, attributed to Jacob Foulk, Morgantown, West Virginia, 1802–1817. Earthenware. H. 8 1/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Earthenware cylindrical storage jar with bold sponged decoration. This has a less red color on the base than some we attribute to Foulk and Thompson, but there are others of this shade with Morgantown provenance.

Jar, attributed to Jacob Foulk, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1802– 1817. Earthenware. H. 7 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This cylindrical string-tie storage jar has green and black brushed slip decoration. The rim has narrow black brushed slip stripes. All of these appear to be more hurried than the other brushed slip examples. Note that the green is brighter than usual when applied directly to a red body. The slip probably included white clay as a substitute for engobe.

Jar, attributed to Jacob Foulk, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1802– 1817. Earthenware. H. 8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This cylindrical string-tie storage jar shows trailed viscous dark slip and brushed white and green slip. The white slip is a de facto engobe, but the green slip appears to incorporate some white slip, as evidenced in the small leaflets.

Jar, possibly John Wood Thompson, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1810–1830. Earthenware. H. 7 3/4". (Courtesy, George R. Allen.) The slip decoration is looser than in the examples illustrated in figs. 9–12.

Jar, probably Samuel Butter, Clarksburg, West Virginia, ca. 1820. Earthenware. H. 10 1/4". (Courtesy, Ceramics and Glass Collection, National Museum of American History.) This cylindrical string-tie storage jar has trailed viscous dark slip and brushed white and green slip. The decoration resembles that on the sherds illustrated in fig. 9.

Sherd, Samuel Butter, Clarkburg, West Virginia. Slipware. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

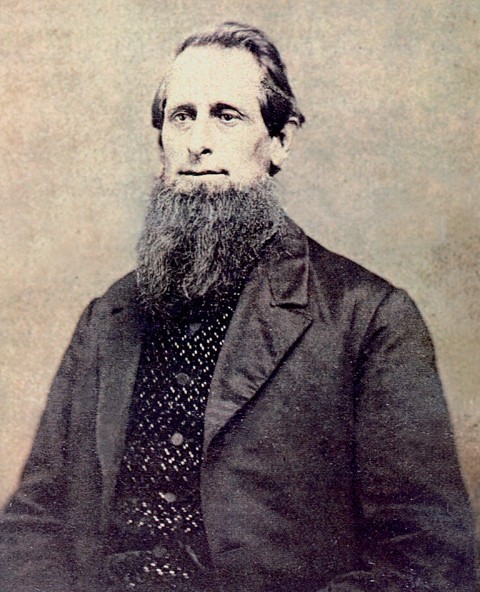

Portrait of John W. Thompson, Baltimore, probably painted in Baltimore, ca. 1830. (Courtesy, R. Crommett.)

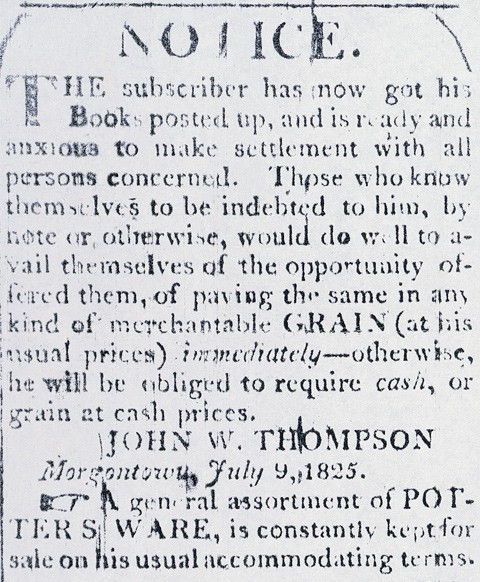

Advertisement of John W. Thompson’s pottery in the 1825 Monongalia Chronicle.

Portrait of Deborah Vance Thompson. (Courtesy, R. Crommett.)

Pitcher, John W. Thompson, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1810– 1830. Earthenware. H. 6 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This pitcher with extruded ribbed handle is impressed “J.W. THOMPSON / MORGANTOWN V” in slanted capital letters.

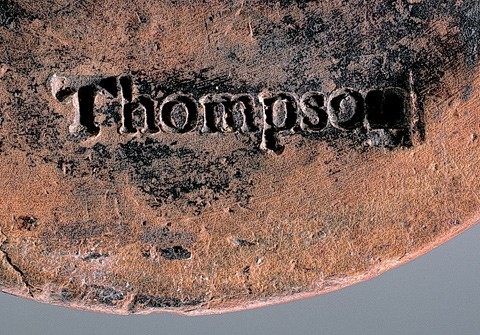

Detail of the mark on the pitcher illustrated in fig. 19. This mark was also found among Lot 88 sherds.

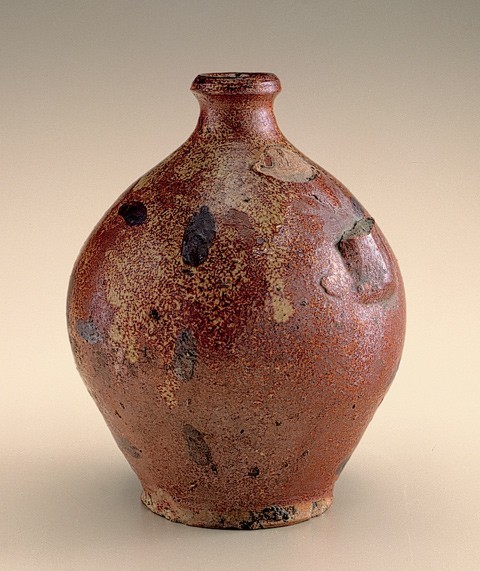

Flask, John W. Thompson, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1810–1825. Earthenware. H. 7". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This flask is stamped “Thompson” on the base. Note that the treatment of the spout lip and the definition of the neck/shoulder transition differ from the signed example illustrated in fig. 22.

Flask, John W. Thompson, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1820– 1840. Earthenware. H. 6 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This flask, impressed “Thompson,” has a beveled lip that was used extensively in Morgantown. A third example of a Morgantown flask, showing a simpler lip, is in the Smithsonian Institution and is labeled a “tickler,” or pint flask.

Inkwells, John W. Thompson, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1830– 1854. Earthenware. H. 2" and 2 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The inkwell at left is impressed “J.W. THOMPSON / MORGANTOWN, VA.”; the one at right is impressed “Thompson.” Three signed inkwells by Thompson are known. This pair differs slightly in shape but has the same fine coggling at the edge of the shoulders. These examples can be compared with the more carefully finished example by Samuel Butter illustrated in fig. 26. The third example, not shown, is signed by Thompson; it is about 50 percent larger and displays a moderately dark, slightly yellow, shade of green.

Detail of the mark on the inkwell at left illustrated in fig. 23.

Detail of the mark on the inkwell at right illustrated in fig. 23.

Inkwell, Samuel Butter, Clarksburg, West Virginia, ca. 1820. Earthenware. H. 2 1/2". (Courtesy, Hardy Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Note that the glaze appears thicker and more lustrous than on the Thompson examples illustrated in fig. 23.

Detail of the mark on the bottom of the inkwell illustrated in fig. 26. Note the lack of the final “s” in Butter’s last name and the absence of “& Co,” which appears in his later marks (see fig. 64).

Jug, Samuel Butter, Clarksburg, West Virginia, ca. 1820– 1850. Earthenware. H. 6 3/8". (Photo, Richard Duez.) Signed on the bottom, this bulbous jug has a high luster lead glaze over a straw- colored slip. Found in southern Harrison County, West Virginia.

Jug, probably Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1805–1840. Earthenware. H. 6 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The thin straw glaze on this jug reveals much of the red clay body.

Jug, probably Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1805–1840. Earthenware. H. 6 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This jug is decorated with alternating spots of manganese in a grid-like pattern.

Jug, probably Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1820 –1850. Earthenware. H. 8 5/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The spout rim of this jug resembles that of the flask illustrated in fig. 21.

Jug, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1820–1850. Earthenware. H. 6 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Note the brushed manganese slip decoration.

Jar, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1820–1850. Earthenware. H. 11 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Brushed manganese slip decoration adorns this early molasses jar. (Molasses was uncrystallized maple sugar.) Several spalls reveal gravel in the body.

Jar, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1820–1854. H. 11 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Two similar examples are illustrated in Walter Hough, “An Early West Virginia Pottery,” pl. 2, fig. 1, where they are referred to as “Molasses Jars.”

Jar, Morgantown, West Virginia, 1840–1854. Earthenware. H. 7 1/4". (Duez collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Although this jar appears primarily black, in bright daylight highlights of green and yellow are visible throughout the glaze.

Bottle, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1850. Earthenware. H. 5 1/4". (Duez Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This bottle was perhaps for ink or boot blacking. It was found in a basement next door to the Lot 88 kiln site.

Jar, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1830. Earthenware. H. 1 7/8". (Duez Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This miniature cylindrical string-tie storage vessel is possibly an ink or ointment jar. It was found in Morgantown.

Jar, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1840–1854. Earthenware. H. 7 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This cylindrical string-tie storage jar has an impressed geometric design created by a roulette that is now in the Smithsonian Institution. This same roulette was used in Morgantown’s stoneware period, which began in September 1854. They probably were made near the end of the earthenware period, since roulettes ?ourished in the early stoneware period. Competition from glassmakers—Albert Gallatin’s glass plant at nearby New Geneva, Pennsylvania, began production in 1807—may have forced potters to speed up production to cut costs. Roulette decoration could be completed in one quick rotation of the jar, whereas carefully placed daubs or strokes of slip involved more time and additional material.

Detail of the roulette design on the jar illustrated in fig. 38.

Rouletting tool, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1840–1854. The roulette is a fired clay disk. (Courtesy, National Museum of American History; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jar, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1840–1854. Earthenware. H. 7 1/2". (Duez Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The geometric roulette design on this cylindrical string-tie storage jar differs from that illustrated in fig. 38. The roulette that made this design is also in the Smithsonian Institution. This roulette was also used on Morgantown stoneware.

Wooden rib, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1840–1854. (Courtesy, National Museum of American History; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This rib is one of several that are preserved in the Smithsonian Institution. The tool was used to form the contours of the lip and neck of storage jar forms.

Jars, Morgantown, West Virginia. Left: ca. 1855. Stoneware. H. 5 3/4". Right: ca. 1830–1854. Earthenware. H. 7". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Note that this earthenware form carried over to the stoneware period; we attribute the innovative decoration to David Greenland Thompson.

Jars, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1820–1854. Earthenware. H. 7 1/2" and 7". (Duez Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These jars were found together in a house some seventeen miles upstream from Morgantown.

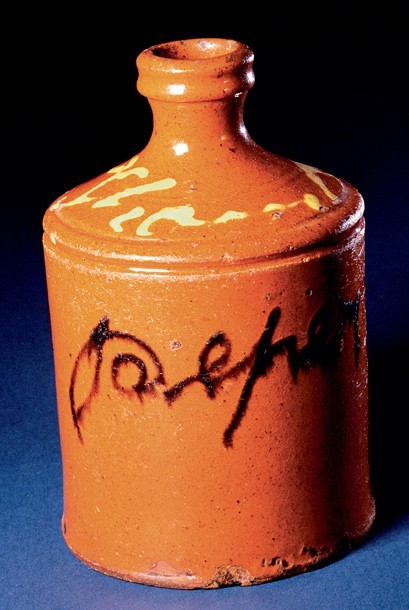

Spice (“Peper”) bottle, David G. Thompson, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1840–1854. Earthenware. H. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, Ceramics and Glass Collection, National Museum of American History.)

Churn, Thompson pottery, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1840–1854. Earthenware. H. 9 3/4". (Courtesy, Ceramics and Glass Collection, National Museum of American History.)

Pitcher, Thompson pottery, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1820– 1840. Earthenware. H. 9 3/4". (Courtesy, Ceramics and Glass Collection, National Museum of American History.)

Pitcher, attributed to the Thompson pottery, Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1850. Earthenware. H. 9 3/4". (Courtesy, National Museum of American History; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The molded spout is the only surviving provincial earthenware example known to us. The molds in the Smithsonian include similar spout designs as well as smaller versions of houses. Molded spouts occur on Staffordshire pottery, and in the 1830s and 1840s Staffordshire potters were moving into East Liverpool, Ohio. A craftsman there might have supplied the Thompsons with molds, although no examples have been seen in that city’s excellent ceramics museum. It is also possible that Thompson employed a Baltimore mold maker, as he maintained contact with this city.

Detail of the spout on the pitcher illustrated in fig. 48.

Spout molds, Thompson pottery, Morgantown, West Virginia. (Courtesy, National Museum of American History; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This collection of graduated molds suggests that a range of sizes may have been produced at the Thompson pottery.

Extrusion dies. (Courtesy, National Museum of American History; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) An assortment of dies used in conjunction with an extruder to produce various handle shapes and profiles.

Tools, Thompson pottery, Morgantown, West Virginia, nineteenth century. (Courtesy, National Museum of American History; photo, Robert Hunter.) A snapshot of some of the common potting tools, such as ribs, scrapers, and finishing implements. The amazing variety of surviving tools collected by Hough, articularly the roulettes and molds, is to our knowledge unmatched by that from any other American provincial pottery of the early to mid-nineteenth century. They are a wonderful, but dismaying, reminder of what has been lost from other potteries.

Slip cup fragment, attributed to John Sloneker, Morgantown, West Virginia, 1817. Earthenware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

James J. Thompson, potter. (Courtesy, R. Crommett.)

Francis W. Thompson, potter. (Courtesy, R. Crommett.)

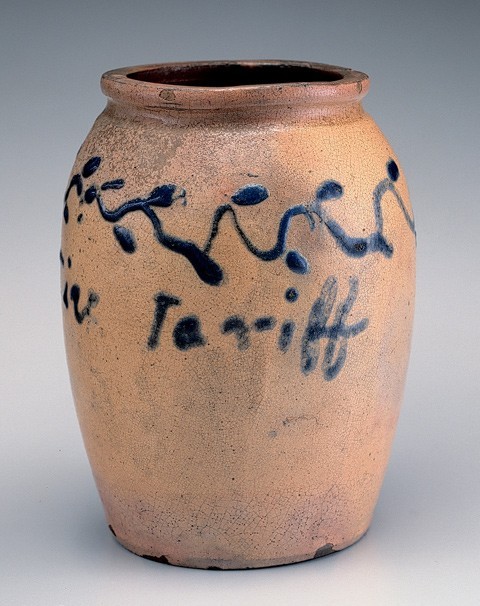

Jar, attributed to William Crichfield, Greene County, Pennsylvania. Stoneware. H. 8". (Duez Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The body of this jar is covered in a buff-colored slip and decorated with trailed and brushed cobalt. The inscription reads: “Potectiv Tariff.”

Salvage excavation at the Samuel Butter pottery, Clarksburg, West Virginia. (Photo, Don Horvath.) A hurried and limited opportunity to observe the remains of the Butter pottery came during construction activities on the site. This illustration shows two stacks of slip decorated plates and dishes unearthed during excavation.

Dish fragments, Samuel Butter, Clarksburg, West Virginia, ca. 1820– 1850. Slipware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This plate shows the use of concentric white slip bands accented with a black slip trailing.

Dish fragments, Samuel Butter, Clarksburg, West Virginia, ca. 1820– 1850. Slipware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dish fragment, Samuel Butter, Clarksburg, West Virginia, ca. 1820–1850. Slipware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This plate has a coggled rim and a more spontaneous use of black and white slip trailing to form the decoration.

Dish fragment, Samuel Butter, Clarksburg, West Virginia, ca. 1820–1850. Slipware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dish fragment, Samuel Butter, Clarksburg, West Virginia, ca. 1820–1850. Slipware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Sherd, Samuel Butter, Clarksburg, West Virginia, ca. 1820–1850. Agateware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This sherd of an agate red and white clay body, sometime referred to as scroddle ware, is the only known example from the Butter pottery.

Sherd, Samuel Butter, Clarksburg, West Virginia, ca. 1820–1850. Earthenware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Note the presence of a final “s” in his last name and the addition of “& Co.” Compare this example with the mark illustrated in fig. 27.

Sherds, Samuel Butter, Clarksburg, West Virginia, ca. 1820–1850. Earthenware. (Photo, Richard Duez.)

Tumbler, Pennsylvania or West Virginia, nineteenth century. H. 4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) From a Morgantown family said to have a potter in its family history. This unglazed example resembles New Geneva tanware though it is less “dry.” Decorated with incised lines and a red slip, the body is very dense and finely finished.

Plate, probably Morgantown, West Virginia, ca. 1800. Earthenware. D. 9". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This coggled-edge slip-trailed earthenware plate was obtained from an “old” family on Grand Street in Morgantown. Morgantown and Clarksburg potters occasionally coggled plate edges.

The pottery produced in what is now Morgantown, West Virginia, is remarkable in several ways. Its decorative elements are diverse and often innovative, as are some of its forms. Its history is recorded more fully than that of most American pottery. And, through the efforts of Dr. Walter Hough, a Morgantown native who became an assistant curator of the Division of Ethnology at the U.S. National Museum, many early specimens, including potter tools, were collected in the nineteenth century and donated to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

There are several other publications that treat some aspect of the Morgantown potteries, the most important being Hough’s seminal history, “An Early West Virginia Pottery.”[1] This article examines the production and development of the earthenware in greater detail and incorporates findings from three episodes of “backhoe archaeology” within the past decade. The first excavation took place in the basement of Morgantown’s Old Stone House, as well as in a trench in front of this late-eighteenth-century building; the second occurred on the property designated as Lot 88, where the potter’s kiln was located; the third, which yielded a large number of sherds, was at a satellite pottery in Clarksburg, West Virginia.

The Setting

Rapid population growth in Virginia’s eastern region spurred inland exploration after 1700. By the second half of the eighteenth century settlers were streaming westward (although the population of the Morgantown area remained sparse until General “Mad Anthony” Wayne’s victory over the Indians resulted in the signing of a peace treaty at Greenville, Ohio, in 1795).

In a 1768 land office lottery, Col. Zackquill Morgan won a settlement right to land adjoining the Monongahela River and Decker’s Creek (fig. 1), although he waited until 1772 before moving from his farm in Bedford, Pennsylvania. Originally called Morgan’s Town, the settlement was laid out by Maj. William Haymond in 1783/84. By that time, Thomas Laidley, who was recruited to the area by entrepreneur Albert Gallatin, had opened a mercantile store.

According to family history James Thompson Sr. of Bel Air, Maryland, came to the area when he was chosen to assist his Revolutionary War commander, Capt. Samuel Hanway, in the task of surveying Monongalia County. In 1787 Thompson took up permanent residence in Morgantown, where three of his sons and three of his grandsons would become potters.[2]

Potters gained a secure foothold in the area because the entire region of southwestern Pennsylvania, mideastern Ohio, and north-central Virginia once lay at the bottom of an extensive lake created by a glacial dam. Over time, fine clay particles settled in layers of considerable depth on the lake bottom. The clays, which included significant amounts of kaolin (porcelain clay), would—millennia hence, in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries— support the region’s large-scale stoneware potteries.

These clays, as well as the high cost of imported pottery, the cheap land, and the prospect of shipping wares downriver to larger markets, encouraged potters to move to Morgantown, the head of navigation.[3] However, downstream competition developed at nearby Greensboro, Pennsylvania, in the early 1800s. This competition may explain why many of the Morgantown examples found in the twentieth century came from areas south and east of Morgantown, rather than to its north. Moreover, by 1815 there were yellow ware potters in Pittsburgh, and Pittsburgh dealers were also importing English queensware via the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers.[4]

The First Anglo-European Potters

In his report for the U.S. National Museum, Hough stated that a pottery was in existence in Morgantown “before 1785” and was operated by “Master Foulk.” However, ceramic historian Gene Comstock has shown that Jacob Foulk Jr. was in Frederick County, Virginia, at least in the early part of 1801.[5] The most direct evidence of Morgantown’s eighteenth-century potting activity is Hugh McNeely’s sale of “the pottery kiln lot,” the south half of Lot 7 (fig. 2), to John Scott, occupation not given, in 1800.[6] Historian James Callahan was convinced that Scott was a potter, but we have not found court records that confirm this.[7] (In any event, potting by Scott would have ceased in 1807 when he was sentenced to five years in jail for stealing a horse.[8]) Callahan also believed that Francis Billingsley was a potter. Billingsley did own Lot 7 from 1814 to 1827 and shared it with Foulk beginning in 1815.[9]

Some of Hough’s dates for particular earthenware pieces do not agree with current research, but his overall timeline for the glazes and forms of wares deserves attention. He states that the “first ware made at Morgantown was porous terra-cotta covered with a yellow lead glaze,” although later he offers conflicting color information: “Terra-cotta covered with glaze giving the reddish-brown color which is said to have been the color of the earliest ware made at Morgantown.”[10]

The difference in color may distinguish the fine tableware from the more utilitarian wares. Hough continues,

During the War of 1812, as [potter] William Boughner of Greensboro, Pennsylvania informs me, “the yellow glazed ware was in good demand. . . . cups and saucers sold at a dollar the set.” Previously the [Morgantown] wares were of the commoner forms for domestic use, such as milk pans, preserve jars, jugs, etc. . . . Teapots, cups, saucers, dishes, and other tableware were turned out [in Morgantown] . . . fragments from the site of the old pottery show its character [fig. 3].[11]

It is probable that Hough’s “yellow glazed ware” was a thin white clay slip rendered yellow by traces of iron. Several extant straw-colored pieces may be what he described (figs. 4-6). Hough then describes the next phase: “‘redware,’ or terra-cotta, covered with transparent lead glaze. In the period around 1800 a number of glazes began to be used, such as dark-brown lead glaze, black iron or manganese glaze, [Flemish] gray ‘china glaze,’ greenish-gray [also called china glaze by the potters] and white, the surviving specimens being interesting and beautiful.”[12] Many key examples of these ceramic types—gifts to the Smithsonian Institution principally from Mrs. Dorcas Haymond, daughter of nineteenth-century potter John W. Thompson—are featured in black and white photographs published in Hough’s history. The names of glazes are presumably those used by Thompson and his sons.

Chronological Account of the Morgantown Potters

JACOB FOULK JR. (FOUKE, FOLK, FULK), CA. 1764–AFTER 1817

Even though two “Jacob Foulks” appear in the 1801 Taxables List for Monongalia County, it is known that Jacob Foulk Jr. and his slaves, Reuben and Samuel, moved to Morgantown in 1801.[13] In 1804 father and son are distinguished in the records, and Jacob Jr., recorded as having three white males above sixteen years in his household, apparently was a builder as well as a potter. He offered to build a brick house for Nicholas Madeira and to supply the bricks.[14] One might have expected him to keep his slaves for digging and pugging clay and making bricks while he did the skilled work. However, evidently he had sold Reuben and Samuel soon after arriving in Morgantown, as no slaves with those names appear in the records nor were blacks declared in his tax entries.

Over the years, he did acquire other help. In 1803 he engaged Charles Snodgrass Jr. as his first recorded Morgantown apprentice. Around 1804 John W. Thompson was his second recorded apprentice.

Payments in pottery were common for Jacob Jr. “Earthenware at the said Foulk’s Pothouse in Morgantown” was his method of paying for land. In the contract for a land purchase in 1804, for example, Jacob Jr. agreed to pay with $600 in crockery for each of two six-month periods. This arrangement hints at the production output of his pottery and also provides some insight into his financial well-being. In 1804 Foulk’s land still was not paid for, however, and the crockery payment was deferred for another year.

Whatever Foulk’s financial status, it could not have been helped by his frequent legal difficulties. Foulk is somewhat remarkable for the number of court cases in which he appears. Charges against him include slander, resisting execution “by force and arms” (he threatened to strike the constable with “an earthen pott”), assault and battery, trespass and battery, wife beating, suing to avoid paying $50 owed for a bet on a horse race, suing to restrain his father-in-law, Elihu Horton, from providing shelter for Horton’s battered daughter, perjury, and two instances of fathering a baseborn child. He was even sued by his father for debts. Hough reports that in order to make lead glaze, Foulk stripped the lead liner from tea chests and oxidized the lead in an open iron pan.[15] It is tempting to suggest that lead poisoning from this practice contributed to his egregious behavior.

In 1803 both John Scott and Foulk were charged by “Margaret ––––––” with bastardy and each paid $50. This suggests that the two men knew each other. Two years earlier Scott may have leased the kiln site on Lot 7 to Foulk.[16] Were this the case, it would be circumstantial evidence that Scott also worked there and was a potter. If Scott had agreed to lease the pottery from businessman Hugh McNeely until he could purchase it outright, this would answer the question of Scott’s trade. As postmaster, keeper of an “ordinary” (tavern), and also owner of a brewery, McNeely would have had the resources to build the pottery as a source of rent or of “shares” income.[17] The fact that Scott was residing with Patrick Johnson in the 1786 Taxables List suggests that he was not then in a position to acquire property in Morgantown proper. In 1770 he had been granted land in Union District “on Decker’s Creek,”[18] but this was probably “undeveloped” forest that was of little value at the time. Scott did purchase the south half of Lot 7 for $100 in May 1800, but he sold it to Ralph Berkshire in 1806.

The year 1805 was the last in which two Jacob Foulks were found in the Monongalia County Taxables List; only Jacob Jr. appears through 1813. In 1807 Foulk purchased the north half of Lot 25, near the kiln site on Lot 88. In 1810 the property passed from James Goff to John W. Thompson. Clay that was removed from the basement of the house on Lot 25 (fig. 7) may represent potting activity, which would have been conveniently located to the kiln across Middle Alley. It also is possible that the clay was simply stored where it would not freeze during winter.

In 1812 Jacob Jr. bought the Lot 88 kiln site (fig. 8). The same year he conveyed it to Thompson, who returned it in 1814. Such frequent property transfers suggest cash flow problems.

In 1815 Jacob Jr. entered into a property sharing agreement with Francis Billingsley for the joint operation of the pottery on Lot 7, and in 1817 his name appears jointly with Billingsley’s in a suit initiated by William Gallahue. However, Jacob Jr. may have been absent from Morgantown by this time. He is said to have gone to Brooke County, Virginia, in 1817,[19] although in 1820 he collected an 1817 debt from Joseph Allen in Monongalia County Court. Neither father nor son is mentioned in any of the wills recorded in Brooke County, Virginia, and there are apparently no “Cemetery Readings” from Brooke County.

Jacob Jr.’s name has not been found on any pottery, but there are slip-decorated sherds (fig. 9) and several intact pieces (figs. 10-12) that we believe are his work.[20] They share slight irregularities in the contours of the walls but are significantly better than those we attribute to John W. Thompson (fig. 13). Jacob Jr.’s putative pieces have a lustrous and viscous dark trailed slip, creating three-dimensional, finely tapered stems supporting two-dimensional brushed slip leaves. Some of the jars display cuprous green brushed on top of white slip, thereby masking the dark background clay. Applying the green leaves over the white ones is a de facto use of engobe. However, there is no engobe on the storage jar with green strokes (see fig. 11) nor on the small leaflets of figure 12. It is probable that the copper was premixed into a white slip or the green would have been much darker.[21] It is partly this distinction among contrasting greens that led us to attribute the cylindrical storage jar in the Smithsonian’s collection to Samuel Butter, another of Foulk’s former apprentices (figs. 14, 15). A further distinction of Foulk’s work is his “fuller” use of available space.

CHARLES SNODGRASS JR., B. CA. 1787

Charles Snodgrass Jr. was apprenticed to Jacob Foulk Jr. in Morgantown in 1803, when he was “upwards of sixteen years of age.” He married Jacob’s daughter, Sarah, the same year. The couple later moved to Trumbull County in northeastern Ohio.

We have no further information concerning him or his wares.

FRANCIS BILLINGSLEY (BILLINGSLY, BILLINGS), DATES UNKNOWN

Francis Billingsley first appears in the 1801 Taxables List but could have been settled in the area as early as 1788 since the intervening records are lost. Based on information from several records, Billingsley was believed to have been involved in the pottery business, and Callahan implied that he was, in fact, a potter.[22] However, Billingsley may also have been content to let others do the actual potting. In his 1815 contract with Jacob Foulk Jr. for the joint operation on Lot 7, which he had purchased from Ralph Berkshire in 1814, Billingsley agreed to provide all materials necessary “for the prosecution of the said business” as well as the venue, and to have “half the wares made and finished in the said shop.”[23] Foulk was also to keep one wheel going half the year and a second wheel the entire year. Billingsley had other interests to pursue; he became a magistrate, legislator, and tavern owner.

We know of no examples of his work.

JOHN W. THOMPSON, 1782–NOVEMBER 1863

John Wood Thompson (fig. 16) was the son of James M. Thompson Sr. (1732–1809) and Sarah Dorcas Wood (b. 1738). The couple is said to have moved to Dorsey’s Fort (just south of Morgantown) from Bel Air, Maryland, “about 1785” when John W. was “four years old”[24]—family history indicates the year was 1787. John W.’s father was a boot maker and a Methodist preacher who is said to have been granted over 1,000 acres in Ross County, Ohio.[25] He had sufficient resources to purchase Lot 118 in 1790 and to build “the fifth house” in Morgantown.[26] This house would pass first to John W., then to David G. Thompson.

In 1803 John W.’s first known venture was a tailoring business “in all its branches.” Since he advertised for a “journeyman tailor,” it is probable that he was an entrepreneur, not an accomplished tailor.[27] The apparent failure of this endeavor may account for his apprenticeship agreement in 1805, when he was twenty-two or twenty-three, with Jacob Foulk Jr. It is possible he began his new career a year earlier, however, since he, his father, and his younger brother, James M. Thompson Jr., were summoned to appear in court in 1804 to testify in a case regarding Foulk’s debt to Davis Shockley. Shockley had agreed to board “one of Foulk’s said boys for one year for two hundred dollars.” The boy was probably apprentice Charles Snodgrass Jr.

John W. was first recorded in the Taxables List for Monongalia County in 1806 as having one white male above the age of sixteen, no slaves, and no horses. In 1810 he purchased Jacob Foulk Jr.’s house (now 313 Chestnut Street) on the north half of Lots 24 and 25 (see fig. 2), a short distance from the pottery kiln on Lot 88. The basement of that house yielded a quantity of clay, both orange and gray-white, and some glazed earthenware sherds (see fig. 3). A later excavation of the street in front of the house yielded numerous additional sherds, which probably are wasters that were used to fill potholes.

In 1812 John W. married his first wife, Mary Webb. Mary had a difficult delivery of twins at the end of her first pregnancy in 1812 or 1813. The daughter, Charlotte, survived, but the boy and Mary did not. That same year none other than Jacob Foulk Jr. sued John W. for assault and battery. Significantly, John W. is said to have advertised “Pottery Ware” for sale under his own name at this time.

In 1815 Foulk conveyed part of the kiln on Lot 88 to John W. but retained use of two-thirds of the pottery for four years, as well as the right to erect two wheels and to “burn or fire” his wares. The deed also required John W. to erect a new pottery within four years. Since Foulk was already engaged in a joint operation with Francis Billingsley, he now had up to four wheels operating simultaneously. If we add at least one wheel for John W., Morgantown was becoming a significant source of pottery.

In the 1816 U.S. Census, John W. Thompson’s household had three white males above sixteen years of age. He owned seven horses and paid sixty cents in taxes. We do not know if all the men noted were potters, but one may have been his younger brother James M. Thompson Jr. (b. 1786), who was a potter. Some of the horses might have been used to power pug mills to prepare clay, but most were probably bought on speculation since John W., like Foulk, also speculated in land.

By 1821 Thompson’s resources had expanded to include four white males above the age of sixteen years, one slave above twelve years and another above sixteen years, and one horse. In 1824 or 1827 he purchased Billingsley’s pottery,[28] and in 1825 he advertised “potter’s ware” (fig. 17), noting that merchantable grain “at his usual prices” was the only alternative to cash payments.

In 1826 his household included one carriage, two horses, one slave above the age of sixteen years, and six white males above the age of sixteen. He paid $2.71 in taxes. Ownership of a carriage reflects growing wealth, and it may be that this was the period in which he commissioned a portrait of himself. The portrait of his second wife, Deborah Vance Thompson (fig. 18) was probably made after 1850. In both portraits husband and wife are elegantly attired, reminding us of Thompson’s earlier interest in tailoring. The portraits set him apart from most provincial tradesmen of the period and certainly indicate a lifestyle dramatically different from that of his former master. Historian Samuel Wiley examined early Morgantown advertisements and noted that in 1829 and 1830 Thompson was engaged in “the mercantile business.”[29] Perhaps he was not actively potting.

In 1830, however, Thompson’s wife was seriously ill and, by most accounts, that was the year the pottery on Lot 88 burned, a loss of $1,600.[30] On September 15, 1830, Thompson established a new pottery on Lot 1, next to the wharf at the bottom of Walnut Street.[31] It would be converted to steam power sometime after 1853, when his son, James J. Thompson, took over its management in 1853.[32]

Thompson may have retired from managing the pottery business before the 1854 conversion of the pottery from earthenware to stoneware production. However, three of his four sons continued the new stoneware business. The 1850 U.S. Census provides insight into the last years of his known involvement.[33]

|

Age |

Sex |

Value of Trade |

Property |

Birthplace |

|

| John W. Thompson |

64 |

M |

Potter |

$200 |

Maryland |

| Deborah (Vance) |

60 |

F |

——— |

Maryland |

|

| David Greenland |

30 |

M |

Potter |

Virginia |

|

| George B |

29 |

M |

Carpenter |

Virginia |

|

| Francis (Frank) |

45 |

M |

Potter |

$300 |

Virginia |

John W. Thompson’s mark appears on several extant earthenware objects. A number of these marked wares are neither well thrown nor well finished and they are relatively common forms (figs. 19-22). They have no decoration other than ribbing and, on the inkwells (figs. 23-25), fine coggling. By way of comparing quality, the inkwell signed by Samuel Butter (figs. 26, 27) is more skillfully thrown and glazed than Thompson’s, even though both of these potters were trained by Foulk. Similarly, a signed Samuel Butter jug (fig. 28) is more refined than other jugs attributed to Thompson and other Morgantown potters (figs. 29-31). Based on body shape and handle attachments the jugs appear to have been made by several hands, yet four of these, plus one not shown, have similar extruded handle cross sections. One jug bears a brushed manganese slip decoration that is attributed to Thompson (fig. 32). The same decoration also occurs on a molasses jar (fig. 33).

There are more storage jars in the study group than there are other earthenware forms (figs. 34-37). They were probably made over a longer period. These jars often have roulette decoration work (see, for example, fig. 37), and existing roulettes and other tools in the Smithsonian’s collection can be matched to these jars (figs. 38-41). These roulettes were also used during the stoneware period of production (post-1854) at Thompson’s pottery.

Another distinctive group of cylindrical storage jars that can be attributed to the Thompson pottery is characterized by distinctive “splotch” or “polka dot” slip decoration (figs. 43, 44). It is unclear who to credit with this innovative decoration. It may have been introduced by John Thompson or possibly his son David Greenland Thompson (discussed below). This type of decoration, as well as others occurring on both earthenware and stoneware forms, helps provide some dating evidence for the sequence of forms from those of John W. Thompson to those of his sons.

DAVID GREENLAND THOMPSON, 1820–1890

David Thompson, often referred to by his middle name, is listed in the 1850 U.S. Census as living with his father, John W. Thompson, and would have trained in his father’s pottery. Although he passed the Virginia bar examination in 1845, he remained a potter.

At least two earthenware vessels, spice bottles that are illustrated in Hough, can be directly associated with David—one has “D. Thompson” in slip, the other has his name incised on the bottle’s base (fig. 45).[34]Apparently he did not use a stamp on the earthenware pieces as he later did on stoneware.

David may be responsible for introducing the roulette wheel decoration as previously illustrated in the earthenware storage jars. He also may have initiated the controlled “polka dot” slip decoration found on several surviving earthenware pieces (see figs. 43, 44), although there may be earlier precedents.

Another form that reflects a crossover between the earthenware and stoneware operations is the conical shape earthenware churn illustrated in Hough (fig. 46).[35] This conical form, as well as a number of stoneware wax sealers, appears on various stoneware pitchers attributed to David. The churn shows freehand decoration that his father and Foulk, so far as we know, did not employ. David probably was also instrumental in the adoption of stamps and molds for applied decoration. His role in several of the most remarkable items in the Smithsonian’s collection needs further examination. Moreover, the amazing polka-dot pitcher appears to have little precedent in American earthenware (fig. 47). Its Morgantown origin is clear even though its maker remains unknown. The slip decoration is related to the various storage jars attributed to David.

Another important pitcher linked to the Thompsons is a large bisqued but unglazed example at the Smithsonian (fig. 48). A number of related molds and other tools must represent the best-documented example of a nineteenth-century American potter’s toolkit (figs. 49-52).

Hough remarked that “the work of Greenland Thompson was not appreciated.” Based on extant examples of his earthenware and stoneware, we feel that David Greenland Thompson was more absorbed by potting than managing the business. Further, we believe he was a much more skillful potter than his father—though, as later years will attest, not as skillful an entrepreneur—and that he used clay and glazes as a poet uses words.

ABNER GREENLAND, 1783–1830

In 1800 Abner Greenland entered into an apprenticeship agreement with the potter Eli Haines in Cecil County, Maryland. Abner probably arrived in Morgantown no later than 1805 since he married Jane Thompson (1790– 1842), John W. Thompson’s sister, on January 5, 1806. Abner appears in two Monongalia County court cases in the same year. In the first, David Bayles v. Jacob Foulk, he and John W. appeared as witnesses in a case regarding a debt due by deed of trust. Later that year, in the second case, Jacob Foulk was the witness when Abner and John W., as co-plaintiffs, sued Davis Shockley for a debt due by note. Since Abner does not appear on the Monongalia County Taxables List, it is likely he was the “white male above sixteen years” residing with John W. Thompson. By 1810 Abner and Jane had moved to nearby Uniontown, Fayette County, Pennsylvania. Their first son, John, “born in Virginia,” became a potter, as did their other sons, Garrett and Norval. It is reasonable to assume that Abner worked as a journeyman potter with Jacob Foulk Jr. and/or John W. Thompson.

We have not been able to identify any earthenware turned by Abner.

JOHN SLONEKER (SLONAKER), 1798–AFTER 1825

John Sloneker, journeyman potter, agreed on May 21, 1815, to work for Jacob Foulk Jr. for “ $11.00 per mo. and board and lodge.” It is probably not a coincidence that on May 10 of the same year, Foulk agreed to operate Francis Billingsley’s pottery. John Sloneker appears next in the records of Bullskin Township, Fayette County, Pennsylvania, from 1817 to 1825. Sloneker may have made the dated slip cup (fig. 53) found near the kiln on Lot 88, because when Foulk deeded it to John W. Thompson, he retained the right to use part of that pottery until 1819.

We do not know where Sloneker was trained, nor do we know of any signed examples of his work.

JAMES M. THOMPSON JR., 1786–AFTER 1850

James M. Thompson Jr., younger brother of John W. Thompson, almost certainly had begun training with Jacob Foulk Jr. about 1804 (recall his part in a court case against Foulk in that year), although no apprentice papers have been located. In 1810 his older brother deeded to him sixty-three acres on Scott’s Run in Maidsville, Virginia, across the Monongahela River. This was probably part of a group of properties deeded in 1809 to John W. by his father, James M. Thompson Sr., in apparent anticipation of the latter’s death. John W. was evidently the de facto administrator of his father’s estate.

The 1850 U.S. Census for Mt. Pleasant Township, Madison County, Ohio, shows James M. Thompson Jr., potter, age sixty-four, born in Virginia, as was his wife, Sarah. We believe this to be John W.’s younger brother. We know of no examples of his work, but he may have been a more experienced potter than his older brother since he apprenticed at a younger age.[36]

FRANCIS M. THOMPSON, B. 1805

Francis M. Thompson, potter, and younger brother of John W. and James M. Thompson, was listed as residing with John W. in the 1850 U.S. Census. He also owned property valued at $300. We have no specific information concerning his potting career.

JAMES J. THOMPSON, 1826–1899

Capt. James J. Thompson’s middle name, Jackson, is in honor of the father of Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, to whom James J. (fig. 54) was related by marriage. James J. was the second of John W. Thompson’s sons to become a potter. He would have trained about 1840 to 1845. In 1853 management of the new pottery on Lot 1 would be turned over to him by his father, although Core places Col. Frank W. Thompson, a younger brother, in charge.[37] One might have expected David G. Thompson to have been the manager, but he was probably too introspective.

No pieces by him are known.

FRANCIS “FRANK” W. THOMPSON, 1828–1900

Col. Frank W. Thompson (fig. 55) was the fourth son of John W. Thompson and the third to become a potter. He left home for “the West” about 1850 and from 1852 to 1855 served with the Oregon Mounted Volunteers in campaigns against the Yakima and other Indian peoples. In 1859 he was listed as potter in Thurston’s Directory of the Monongahela and Youghiogheny Valleys.[38] He then served on the Union side in the Civil War, rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel. There is no mention of him in the 1870 U.S. Census of Manufacturing, but David Greenland Thompson, who filed the census report, was paying wages to someone, and there is one crock impressed “F. W. Thompson.” In 1873 Frank W. opened the first steam-powered flour mill in the borough at the Walnut Street pottery lot at the wharf.[39] This new operation probably ended his involvement in the pottery business. By 1880 he was a justice of the peace and he eventually became mayor of Morgantown.

WILLIAM C. CRICHFIELD (CRICKFIELD, CRIHFIELD, CHRISTFIELD, SCHRICHFIELD), 1784–1863

William C. Crichfield, who was born in New Jersey, moved with his family to Greene County, Pennsylvania, before 1816, when his father, Absolam, died. In 1821 William Crichfield, potter, was taxed in Whitely Township, Greene County, Pennsylvania.[40] At that time he was almost certainly an earthenware potter. Whitely is ten to fifteen miles from Maidsville, (now West) Virginia, where Crichfield is buried in his family’s cemetery across the river from Morgantown.[41] Hough states that William Crichfield was an employee of the Thompson pottery but does not indicate when.[42] He refers to a salt-glazed jar bearing “Home manufacture. Independence. High tariff. William Crihfield. August 1844.” in cobalt blue brush work. In 1842 the Whig administration passed a protective tariff act. Tariffs were a principal source of federal funds, and in 1844 the Democrats’ campaign promise included changing the tariff to one based on valuation of imports. This salt-glazed jar reflects support for the unsuccessful Whig campaign of 1844. The jar’s present location is unknown.

A slightly buff-colored, salt-glazed stoneware jar is known extolling “Potectiv Tariff” in cobalt decoration (fig. 56). It displays a sinuous vine decorated with oval leaves. This “tariff jar” may also have been made by Crichfield. Although we have no clear evidence of Crichfield’s earthenware products, there is another possible clue. A so-called sugar purifier that is inscribed “jfc” is illustrated in Hough.[43] The purifier may have been made for Crichfield’s younger brother, John, who died in Doddridge County, West Virginia, in 1865. However, as we have not learned John’s middle name, this remains speculation.

Crichfield does appear in minor court records in Monongalia County from 1841 to 1852, and Wiley states that Crichfield established his own pottery a few miles downstream at [West] Van Voorhis (Collin’s Ferry), but does not give a date.[44] It is possible that he produced stoneware there, as stoneware production had begun by 1824 by J. Bower of nearby Frederick Town.[45] The Boughners had attempted stoneware production as well, but the first results were “desultory.” Hough states that William Boughner had informed him that their first (successful) stoneware production was in 1849. Crichfield does not appear in the 1850 census and is listed as “farmer” in the 1860 census.

The Clarksburg Pottery

SAMUEL BUTER (BUTTERS), 1798–1863

Members of the Butter family appear in the Taxables List of Monongalia County as early as 1806. Samuel Butter was born in Pennsylvania, the son of a miller who apprenticed him in Morgantown before moving to Ohio. According to the original town plan, Butter had established Clarksburg’s first documented earthenware pottery by 1819. It was located on the north side of Main Street on the upper or western half of Lot 20. The earliest reference to the pottery is in a deed dated November 6, 1819, which describes this lot as the one “on which the Potter’s shop now stands.”

John G. Jackson, Clarksburg’s leading entrepreneur, bought Lot 20 in 1807 for $250. Jackson then leased the property to Thomas Synott, shoemaker, who was to pay $25 annually. After ten years, by which time the principal presumably would have been paid off, Synott divided the lot and sold the half with the pottery. The likely interpretation is that Jackson arranged for the pottery to be built and, just as they had helped other tradesmen, Synott, George Towers, and the buyer were silent partners with Jackson in establishing the pottery in Clarksburg. By the 1850 census, Samuel Butter, fifty-one years old, listed his occupation as miller. He had two sons, Samuel Jr., age fifteen, and John, age twenty-one, whose occupations are not given. Butter died in 1863 from a gunshot injury. While tending his nearby grist mill/saw mill, a revolver slipped from his pocket and went off.

We do not know the names of his potting assistants nor the final date of his potting activity. A signed ring jug with an orange-hued glaze is known, as is the sophisticated jug in figure 28. Two stacks of broken plates (fig. 57), revealed during construction and subsequent excavation at the Clarksburg site, show a variety of trailed slip lines (figs. 58-62) that include the type of viscous dark slip used by Foulk in Morgantown. However, some of the compositions are rather random and appear trite compared with those found on the Butter’s sherd (see fig. 15) and the putative Foulk sherds (see fig. 9) discovered next to the kiln on Lot 88 in Morgantown.

Interestingly, few of the plate sherds at either site have coggled edges. A single example of an agate or “scroddled” lay body was found (fig. 63). Several examples of stamped “Butter” and “Butters” marks (figs. 64, 65) were recovered along with a sherd (fig. 65) that displays carefully trailed “yellow” slip forming reciprocal, separate S scrolls which, when viewed from a distance, create a helical border. There is also a sherd (not shown) with white slip disks that are bordered with dark beads and centered with dark slip disks.

Bearing in mind that there are limited numbers of sherds and intact wares available for comparison, some observations are offered: Butter appears to have acquired more of Foulk’s vocabulary than had John W. Thompson; Foulk was deft and fast, whereas several of Butter’s early pieces are more labored and show more careful control; unlike Foulk, Butter did not use engobe under portions of his green slip or apparently much white slip in his cuprous slip, thus rendering the green in those portions much darker than Foulk’s greens; and the finish on Butter’s inkwell in figure 26, the jug in figure 28, the sherd illustrated in figure 15, and a ring jug (not shown), are superior to John W. Thompson’s surviving signed wares. (Admittedly, the irregularity of the surfaces of the underlying clay in John W. Thompson’s wares prejudices the impression made by the brushed slip and the glaze.) Also, Butter’s use of raised bead outlining is not seen in Morgantown wares.

Conclusion

As with any investigation into regional ceramic typologies, much research remains to be done. While many of the attributions in this article are based on years of experience in collecting examples found locally, there are always pieces that defy firm identification (figs. 66, 67). This overview of Morgantown earthenwares provides a glimpse into the range and diversity of this manufactory. As a companion to this article, a future article will examine the manufacture of stoneware in Morgantown beginning in 1854 and will discuss and illustrate some of the most unusual forms and decorative devices in America.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge the efforts of Ron Chrislip, who prepared an educational display of Morgantown pottery at the Old Stone House and presented a program at the Historical Society in Clarksburg, West Virginia.

Walter Hough, “An Early West Virginia Pottery,” in Report of the National Museum (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1901), pp. 513–22.

James Thompson took the oath of loyalty in 1776, at age sixteen, in Harford County, Maryland. George Washington mentions visiting Hanway’s surveying office at Pierponts (just east of Morgantown) in 1784 while looking for possible routes for a canal to connect the Potomac to the Monongahela River.

The early Morgantown potters faced local competition for their well-to-do customers in the form of Ralph Berkshire’s 1806 advertisement for “china” wares. See James M. Callahan, History on the Making of Morgantown, West Virginia (Morgantown, W.V.: West Virginia University Studies in History, 1926), p. 136. Berkshire also sought some of Jacob Foulk Jr.’s wares to resell (see note 8 below), but had to go to court in 1809 in an attempt to obtain the wares due to him. By 1806 Berkshire owned both halves of Lot 7, having bought the kiln portion from John Scott in 1803. Perhaps Foulk had an unrecorded lease arrangement for use of this kiln and was to pay in crockery ware rather than money. The first steamboat reached the wharf in Morgantown in April 1826 but service would have been seasonal. See Samuel T. Wiley, History of Monongalia County, West Virginia: From Its First Settlements to the Present Time . . . (Kingwood, W.V.: Preston Publishing Company, 1883), p. 541.

Diana Stradling and J. Garrison Stradling, “American Queensware: The Louisville Experience, 1829–1837,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001): 165–66.

Hough, “Early West Virginia Pottery,” p. 513; H. E. Comstock, Pottery of the Shenandoah Valley Region (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, 1994), p. 13.

Earthenware potters were working in nearby Pennsylvania, particularly in northern Fayette County, by 1791. The term “potter” had another definition in the eighteenth century, “a maker of metal pots,” hence it may refer to laborers working in the iron foundries springing up locally. This confounds the records. The following are believed to be late-eighteenth-century earthenware potters: Christian Tarr, 1791, Uniontown, who also built a pottery in Waynesburg that was operated in 1799 by Nicholas Hager (see James Hadden, A History of Uniontown: The County Seat of Fayette County, Pennsylvania [Akron, Ohio: New Werner Company, 1913], p. 808); Edward Bittle, 1794–1800, Cumberland Township, Greene County; Henry Tarr, 1794–1811, Washington; John Bower, 1795–1828, Frederick Town; Jacob Webb, 1797, Bridgeport (South Brownsville), Fayette County; and John Baners, who in 1798 paid for milling at Heaton’s mill, near Carmichaels, with earthenware (see Helen Elizabeth Vogt, Westward of Ye Laurall Hills, 1750–1850 [Parsons, W.V.: McClain Printing Company, 1976], p. 363). There was also an Adam Funk potter/pottery merchant, 1785–1800, in Pittsburgh. Data without citation sources are from James B. Whisker, Pennsylvania Potters: 1660–1900 (Lewiston, N.Y.: Edwin Mellen Press, 1993), which refutes Hough’s conjecture that Morgantown had the first pottery west of the Appalachian Mountains.

Callahan, Making of Morgantown, p. 130.

Of the principal candidates for “first potter,” only John Scott’s name appears before 1801. He was on the 1786 Taxables List residing with Patrick Johnson. The years 1788 to 1800 are missing, but the 1801 list includes Francis Billingsley, who acquired Lot 7 in 1814 and conveyed it to John W. Thompson in 1827. Jacob Foulk Jr. was in Morgantown in 1801 and purchased Lot 90, which is described as “Foulk’s Pottery on the S.W. corner of Front St. and Bumbo Lane.” The “appurtenances” on Lot 90 are not named in the deed to Foulk. The deed from John and Nicey Evans was made out to Nicholas Madeira but his name is crossed out and Foulk’s name written in above it. This is the same lot on which Foulk would oVer to build a brick house for Nicholas Madeira. After several suits and countersuits Foulk sold it to Christian Madeira in 1806—the same year that Berkshire bought Lot 7. For a fuller account of his tangled transactions with the Madeira brothers, see Comstock, Pottery of the Shenandoah Valley Region, pp. 405–6.

The most accessible chronology of deeds to Morgantown lots is contained in the appendix of Callahan’s Making of Morgantown. This is the source of all subsequent references to lots.

Callahan, Making of Morgantown, p. 309.

Hough, “Early West Virginia Pottery,” p. 515.

Ibid., pp. 514–15.

Ibid., p. 515.

Comstock, Pottery of the Shenandoah Valley Region, p. 404.

Lot 112, the “vacant brick kiln lot,” is on the southeast corner of High and North Boundary Streets, not far from Lot 90. However, Foulk may have used a pottery kiln for firing bricks.

Hough, “Early West Virginia Pottery,” pp. 414–15.

Wiley (History of Monongalia County, p. 260) states that Foulk had a pottery on Lot 90, which he owned until 1806. The clearest evidence is Foulk’s oVer of his house in Morgantown—“where he had his pottery kiln”—as security to William Tingle, who was assisting Foulk in the acquisition of land on the Cheat River. We do not know whether Foulk was able to use the kiln after the sale of Lot 90 to Christian Madeira. He may have made an unrecorded arrangement with Ralph Berkshire to use the pottery on Lot 7.

Ibid., pp. 579, 586; Callahan, Making of Morgantown, p. 121.

Wiley, History of Monongalia County, pp. 39, 669.

Comstock, Pottery of the Shenandoah Valley Region, p. 406.

A comparison of early Morgantown sherds with those on display in the Hagar House Museum in Hagerstown, Maryland, reveals very little similarity and casts doubt on suggestions that Foulk trained in Hagerstown. There is a closer relationship to Shepherdstown sherds formally owned by Mr. J. Wimer. Shepherdstown lies in the northeast corner of Jefferson County, West Virginia, formerly Frederick County, Virginia, where his name appears in court records.

There is a large green inkwell (not shown) that is signed John W. Thompson, but its green glaze is less bright than the green seen in the pieces attributed to Foulk.

Callahan, Making of Morgantown, p. 130.

Billingsley also may have started a pottery on Mrs. Kelly’s lot, probably Lot 12, and later sold it to John W. Thompson, perhaps in 1824. However, Thompson’s only known purchase within this time frame was Lot 7.

Hough, “Early West Virginia Pottery,” p. 513.

Glen A. Thompson, <glent@gte.net>, March 16, 1999, entry s-1.

Hough, “Early West Virginia Pottery,” p. 513.

Earl L. Core (The Monongalia Story: A Bicentennial History, 5 vols. [Parsons, W.V.: McClain Printing Company, 1974–1984], 3: 311–12) implies that John W.’s tailor shop was successful, but his turn to potting casts doubts on this.

Callahan, Making of Morgantown, p. 360.

Wiley, History of Monongalia County, p. 580.

Callahan (Making of Morgantown, p. 130n) placed the fire in 1830.

Wiley, History of Monongalia County, p. 260.

Core (Monongalia Story, 3:51) states that John W. operated the pottery until 1853, when his son, Capt. James Thompson, “came into possession [and] afterwards attached steam to it. . . .” The potter’s steam engine was only 5 hp; 1870 Industrial Census.

There were three other residents: Charlotte (Webb) Sears, Dorcas S. Thompson, and twelve-year-old Henry C. Madeira, who may have been an apprentice. Dorcas Thompson Haymond would later donate many of the pottery’s remaining tools to the National Museum. When the Thompson home burned in 1909, any remaining ledgers and correspondence were lost. The portraits were virtually all that was rescued.

See Hough, “Early West Virginia Pottery,” pl. 1, fig. 5, and pl. 5, fig. 1, respectively.

Ibid., pl. 5, fig. 3.

The authors would welcome photos of his Ohio products for a planned article on Morgantown’s stoneware era.

Wiley, History of Monongalia County, pp. 467, 468; Core, Monongalia Story, 3: 405.

George H. Thurston, Directory of the Monongahela and Youghiogheny Valleys: Containing Brief Historical Sketches of the Various Towns Located on Them . . . (Pittsburgh, Pa.: A. A. Anderson, 1859).

Wiley, History of Monongalia County, p. 579. One reference calls it a corn mill. However, corn originally was defined as the principal grain of a region, and in this case the principal grain was wheat. Wiley calls it the first flouring mill in the borough limits and states that Col. Francis Thompson had installed a 56-hp steam engine in 1873.

Whisker, Pennsylvania Potters, p. 83.

Monongalia Cemetery Readings, Dille collection, West Virginia Regional History Collection, Morgantown.

Hough, “Early West Virginia Pottery,” p. 516.

Ibid., p. 2, fig. 2.

Wiley, History of Monongalia County, p. 260.

Wiley, History of Monongalia County, p. 260.

See Phil Schaltenbrand, Stoneware of Southwestern Pennsylvania (Pittsburgh, Pa.: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1996), pp. 11, 12; and Phil Schaltenbrand, personal communication, September 2003.