Kiln and waster mound at the Magee stoneware shop of the Osceola cluster. (Photos, Christopher T. Espenshade.)

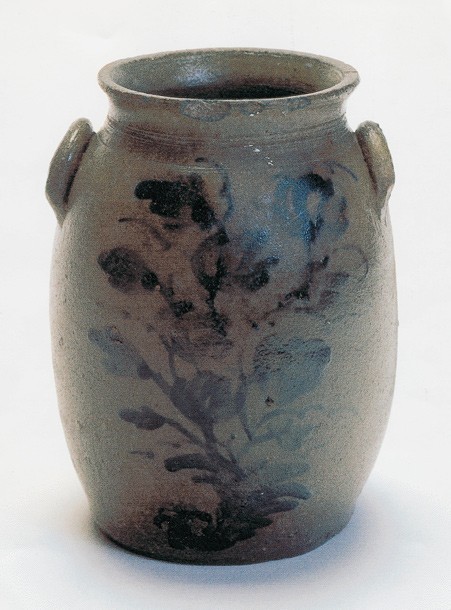

Storage jar, attributed to J. M. Barlow, Alum Wells or Oceola, Washington County, Virginia, 1880–1896. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 13". This vessel has been attributed based on its handle and rim forms and its decorative motif.

Clay Bottoms, an old back channel of the Middle Fork of the Holston River, at which potters from the Osceola shops quarried clay.

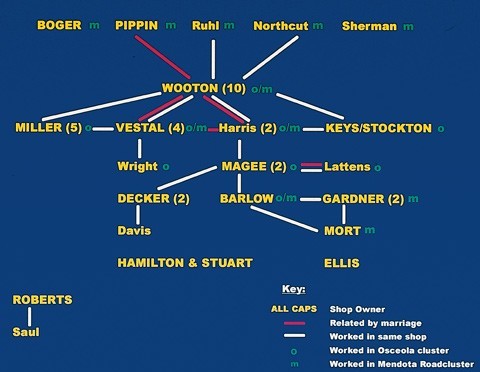

Relatedness diagram of the stoneware potters of Washington County, Virginia.

In 2001–2002, Skelly and Loy completed the survey of historic pottery-making in Washington County in southwestern Virginia.[1] The survey built on previous work by Klell Napps and Roderick Moore. Archival research was undertaken to identify potters and place them in the landscape, and an archaeological survey was conducted at thirty locations suspected of being former pottery shops (fig. 1).

The archival research indicated that earthenware was produced locally by 1780; stoneware appeared by 1850. Major clusters of earthenware shops developed in Osceola and stoneware ones on Mendota Road. The stoneware was typical of the pan-Northeast tradition of salt glaze over freehand, with cobalt underglaze decoration (fig. 2). The fieldwork included revisits to two previously excavated stoneware kilns, the discovery and sampling of seven stoneware shops, and the recording of the source of clay for several of the Osceola shops (fig. 3).

An interesting aspect of the Washington County study was the high degree of relatedness among the stoneware potters. Burrison and Zug have noted the clannish nature of pottery making in the South, and Washington County fits the pattern.[2] Thirty-eight of the forty-three known stoneware potters in the county are linked by descent, marriage, or shared workplace (fig. 4). Potting followed bloodlines: the Wootons, Vestals, Millers, Magees, and Gardners, for example, featured multiple generations of potters, which is consistent with the lack of formal potter apprenticeships found in the county records.

The major potting families strengthened their network through marriage. In most cases these links were in all likelihood simply the result of marrying within one’s social circle. In other cases, however, the individual marrying into a clay family appears to have had no prior potting experience.

The potters were also linked as coworkers. It was common for many of the county potters to work in multiple shops with different coworkers as shops opened, evolved, moved, or closed. By 1870, it appears that there were few strangers in the pottery business in Washington County.

Fluidity, a second trait of the potters, refers to the ease with which a potter could move from one shop to another. In Washington County, the high relatedness allowed much fluidity. For example, although the Wootons were an established potting family, some remained in the Osceola shops even after John T. Wooton opened his shop on Mendota Road. Likewise, excavations at the Gardner kiln yielded more stamps of "E. W. MORT ALUM WELLS, VA and “J. M. BARLOW” than of “J. W. GARDNER & SON / CRAIGS MILL, VA.,” and there is no question that Gardner owned this shop and that Mort and Barlow had their own shops elsewhere on Mendota Road at that time. Clearly, Mort and Barlow were making pottery at the Gardner shop and the Gardners were allowing them to continue using their own stamps.[3]

The high degree of relatedness among the potters made it easy for a potter to follow work; by the same token, that very fluidity would have acted as a buffer against shortfalls of clay, fuel, orders, and/or capital. Washington County stoneware potters reaped the full benefits of fluidity without having to move beyond their local network of shops. The use of foreign stamps at the Gardner kiln might reflect some sort of etiquette associated with the movement of potters between shops. As research continues in the county, additional ties should be recognized.[4]

Christopher T. Espenshade

Cultural Resource Specialist

Skelly and Loy, Inc.

<cespenshade@monroeville.skellyloy.com>

The work was conducted under a Virginia Department of Historic Resources Cost-Share Grant; funding partners included Washington County, the Washington County Preservation Foundation, and the William King Regional Arts Center (WKRAC). The project built on the extensive previous work by the Cultural Heritage Program at the WKRAC. The Wolf Hills Chapter of the Archeological Society of Virginia and Marcus King of the WKRAC assisted in the €eldwork. See C. T. Espenshade, Skelly and Loy, Inc., Monroeville, Pennsylvania, “Potters on the Holston: Historic Pottery Production in Washington County, Virginia” (report on €le, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Richmond, 2002).

John A. Burrison, Brothers in Clay: The Story of Georgia Folk Pottery (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1983), and Charles G. Zug III, Turners and Burners: The Folk Potters of North Carolina (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1986).

It has been suggested by some researchers that the presence of foreign stamps at a shop site simply reects that the potter in residence was copying his competitor’s wares. However, the relative frequency of the Mort and Barlow stamps at the Gardner kiln suggests that Mort and Barlow were producing pottery at the Gardner shop. Moreover, the variability in rim and base forms at the Gardner shop suggests the work of multiple potters.

A proposal is pending for test excavations at the Mort kiln under the Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Threatened Sites Program. Due to landowner issues, the Mort kiln was not examined in detail during the 2001–2002 survey. The site features an extensive waster pile and intact kiln elements. A very brief examination of sherds suggests a wide variety of rim forms, possibly indicating the presence of multiple potters there as well.