Sherds of a Japanese Water Drop ware teapot found in an 1870s context at the Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm, Newbury, Massachusetts. Note the charring on the base of the teapot. (Photo, Michael Hamilton.)

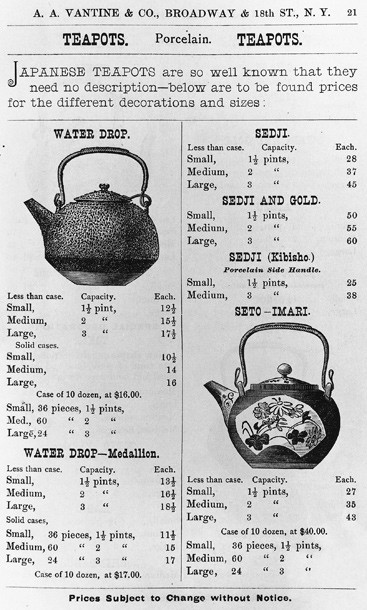

Advertisement for Japanese teapots from an 1890s catalog produced by A. A. Vantine & Co. of New York. Water Drop teapots are here offered wholesale in a variety of sizes. (Courtesy, The Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection.)

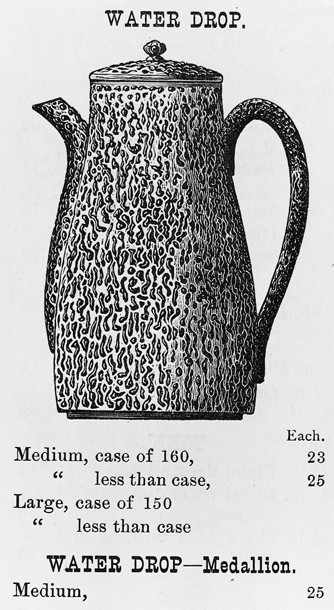

A Water Drop chocolate pot offered for sale by Vantine’s in its 1890s catalog. (Courtesy, The Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection.)

Teapot, Japan, 1870–1890. Earthenware. H. 4 3/4". An intact example of a Water Drop pattern. (Author’s collection; photo, Michael Hamilton.)

Over the years I have puzzled over an odd-looking type of ceramic ware found at archaeological sites in New England, usually represented by a single potsherd. It is a high-fired earthenware so dense it resembles dry-bodied stoneware, with a thick brown glaze that seems to curdle atop the surface of the pot (fig. 1).

An example of this ware found at the Narbonne House in Salem, Massachusetts, during excavations there in the 1970s was identified as German stoneware, but, as is usual in archaeology, the analysts were more interested in the preponderance of the ceramics than in this single, seemingly anomalous, find and did not undertake research into its history.[1] A similar single sherd among the ceramics recovered from excavations at a nineteenth-century boardinghouse in Lowell, Massachusetts, also generated little interest—our analysis did not even mention the ware because the single sherd was not statistically significant in the collection.[2] In the late 1980s, we found another single potsherd of the ware, this time beneath the kitchen floor of the Spencer-Peirce-Little House (SPL) in Newbury, Massachusetts; this was a rim sherd—a lid seating for a vessel like a tea canister.[3] Again it was a single sherd, found in a nineteenth-century context but not considered worthy of much attention. But in 1996 excavations at SPL began to turn up numerous examples of what my students referred to as “wormy ware,” “dog-hair ware,” or “ugly ware.”

Soon we had enough fragments to make up at least one teapot and one tea canister, and I realized I needed to know what this ware was and what significance it might have, if any, to my interpretation of the site. A colleague in art history suggested the pottery was Japanese, so I began to look into the literature on Japanese pottery. None of the art books carried anything that resembled my “wormy ware,”[4] but I soon learned that after the United States opened trade with Japan in the Meiji period (1868–1912), Americans were seized with a passion for goods, particularly decorative art objects, from Japan.[5] Japonisme, as the craze was known, was fed by the ramped-up production of Japanese kilns and factories, which churned out goods for export that American consumers adored but that lovers of fine art declared gaudy and grotesque—one writer declared that “even in an industrial museum their influence would be pernicious.”[6]

The definitive attribution for my mysterious “wormy ware” I found in trade catalogs for A. A. Vantine & Co. of New York, importers of fine Oriental art and furnishings.[7] My teapot and tea canister fragments were indeed among the vessel forms produced in Japan for export during the Meiji period (fig. 2). The Vantine catalogs refer to the ware as “Water Drop” and claim that it was so popular and well known it needed little description. A catalog from the 1890s explained that the ware was a porous earthenware, called “Water Drop” from the resemblance of the glaze to drops of water; made in teapots and water bottles, the latter used in hot countries to keep water cool by placing them in a draft, evaporation taking the place of ice. The teapots are known all over the country and need no special mention. Some have a medallion with paintings of flowers and shrubs in glazed paint on the side; those are known as Water Drop Medallion.[8]

The catalogs showed teapots and chocolate pots (fig. 3) and mentioned, but did not illustrate, Water Drop Medallion, nor have I seen any examples from archaeological or other contexts. Soon after my discovery in the archives, I came across an intact example of a Japanese Water Drop teapot at a local flea market (fig. 4). Like the example found at SPL, it is small in capacity and shows evidence (i.e., slight charring) of having been placed atop a burner of some sort; the base of each teapot has three small bumps that may have facilitated placing the vessel upon a burner.

Beyond the craze for things Japanese, the Victorians also found anything considered rustic to be very appealing as an element of household decor. Water Drop ware exhibits a certain rustic character, and this, along with its links to japonisme, may have been at the root of its appeal to Victorian Americans.[9] Archaeologists would do well to consider the cultural context in which this seemingly innocuous and, to many a modern eye, unattractive ware was used. It enabled its owners to express metaphorically an aesthetic of rusticity and to exhibit a knowledge of things Oriental. The number of sherds we find may be statistically insignificant but even a single Water Drop teapot carried complex meanings for its owners and for those invited to partake of tea poured from it.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My research on Water Drop ware was conducted in 2001 under the auspices of a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship for Advanced Study at The Winterthur Museum and Library. I am especially grateful to Neville Thompson, former librarian at Winterthur, for guiding me toward the A. A. Vantine & Co. trade catalogs in the Winterthur collection. I also thank Grace Ziesing for sharing with me her notes on the family history project she is conducting.

Mary C. Beaudry, Ph.D.

Associate Professor of Archaeology and Anthropology

Department of Archaeology

Boston University

<beaudry@bu.edu>

Geoffrey P. Moran, Anne E. Yentsch, and Edward F. Zimmer, Archeological Investigations at the Narbonne House, Salem Maritime National Historic Site, Massachusetts, Cultural Resources Management Study, no. 6 (Boston: National Park Service, North Atlantic Regional Office, 1982).

David H. Dutton, “‘Thrasher’s China’ or Colored Porcelain: Ceramics from a Boott Mills Boardinghouse and Tenement,” in Interdisciplinary Investigations of the Boott Mills, Lowell, Massachusetts. Volume III: The Boardinghouse System as a Way of Life, edited by Mary C. Beaudry and Stephen A. Mrozowski, Cultural Resources Management Study, no. 21 (Boston: National Park Service, North Atlantic Regional Office, 1989), pp. 83–120.

See, e.g., Mary C. Beaudry, “Scratching the Surface: Seven Seasons at the Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm, Newbury, Massachusetts,” Northeast Historical Archaeology 24 (1995): 19–50, and Mary C. Beaudry, “Farm Journal: First Person, Four Voices,” Historical Archaeology 32, no. 1 (1998): 20–33.

Kikusaburo Fukui, Japanese Ceramic Art and National Characteristics (Tokyo: N.p., 1926); Barry Till and Paula Swart, The Flowering of Japanese Ceramic Art: Late 16th Century to the Present/L’épanouissement de l’art céramique japonais de la fin du seizième siècle à nos jours, exh. cat. (Victoria, B.C.: Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, 1983); Tadanari Mitsuoka, Ceramic Art of Japan, 5th ed. (Tokyo: Japan Travel Bureau, 1960).

William Hosley, The Japan Idea: Art and Life in Victorian America, exh. cat. (Hartford, Conn.: Wadsworth Atheneum, 1990); Siegfried Wichmann, Japonisme: The Japanese Influence on Western Art since 1858 (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1999).

A Professor Morse, as quoted by James Lord Bowes in A Vindication of the Decorated Pottery of Japan (Liverpool: Printed for private circulation by D. Marples and Company, 1891); in this book Bowes defended himself against criticism by Morse and others of his earlier work, Japanese Pottery (Liverpool: E. Howell, 1890), in which he had gone so far as to suggest that some examples of “Modern” Japanese pottery possessed artistic merit.

A. A. Vantine & Co., Illustrated Catalogue of A. A. Vantine & Co., Importers from the Empires of Japan China India Turkey Persia and the East, Broadway and 18th Street, New York (New York: A. A. Vantine & Co., 1880). Although there are several Vantine catalogs in the Winterthur Collection of Printed Books and Periodicals and one in the Trade Catalogue Collection of the Library at the University of Delaware, none produced after circa 1900 includes Water Drop ware among its offerings, so one might deduce that the ware went out of production and/or popularity before, or by the end of, the Meiji period.

Grace H. Ziesing, in her notes on her family history that she generously shared with me, records that A. A. Vantine & Co. was owned and operated by one of her ancestors, James Irving Raymond, who passed it on to his son Irving. The business originally operated at 827/829 Broadway, New York, but in 1913 it moved to 5th Avenue and 39th Street. Irving sold the business in 1922; Vantine’s no longer exists.

Vantine & Co., Illustrated Catalogue, p. 5.

Katherine C. Grier, “Material Culture as Rhetoric: ‘Animal Artifacts’ as a Case Study,” in American Material Culture: The Shape of the Field, edited by Ann Smart Martin and J. Ritchie Garrison (Winterthur, Del.: Henry Francis Du Pont Winterthur Museum, 1997; distributed by University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville), pp. 65–104, quote on p. 96.