Fluted cups, China, early eighteenth century. Porcelain. Left: H. 3". (Photos, courtesy of the author.) The exterior is decorated with delicate flowers over the glaze.

Interior of the cups illustrated in fig. 1. Overglaze flowers ornament the interior surfaces, as well.

Cup, China, early eighteenth century. Porcelain. H. 2 ". This hexagonal cup is adorned on the exterior with a floral decoration.

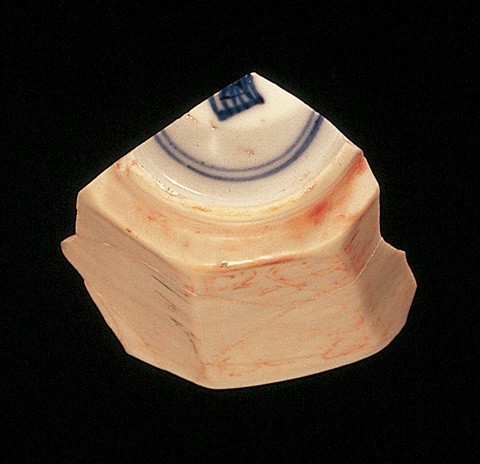

Base of the cup illustrated in fig. 4 displaying unidentified underglaze mark.

Box, China, early eighteenth century. Porcelain. D. 4 1/8". (Courtesy, Stamen Collection.) This small fluted container, provided for comparative purposes, is similarly decorated with a delicate floral motif.

Sherds of Chinese porcelain have been found at the site of Old Mobile, Alabama, which was occupied by the French from 1702 to 1711. The settlers at Old Mobile traded with the nearby Spanish settlements of Pensacola, and also with Havana and Veracruz, so it is likely that the porcelain came to Old Mobile via the Manila galleon trade. Most are decorated with cobalt blue but some were painted with overglaze red and gold enamels. Although some have been discussed in previous articles (the excavation under the direction of Dr. Gregory Waselkov began in 1989), continuing excavations have turned up additional sherds painted with red and gold enamels that are worthy of further comment.[1]

The sherds of thin, fine-bodied porcelain were most likely produced at Jingdezhen, the porcelain-making city in southern China. They are of a type called Chinese Imari, because they copied Japanese wares shipped from the port of Imari. The pieces were made during the latter part of the Kangxi period (1662–1722) of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), by which time Chinese potters had the skill to manufacture pieces of any size and with almost any kind of decoration.

The Chinese had been making porcelain since the Sui dynasty (581–618), but Europeans could not manufacture true porcelain until 1710, when the Meissen factory in Germany was started. Chinese porcelain was coveted in Europe and in European colonies because of its white, dense body, which was resonant when struck, impervious to liquid, and translucent. Stoneware and earthenware did not possess these traits, making them less desirable alternatives.

Chinese and Japanese Imari wares were produced strictly for export, and European customers eagerly collected them. The usual palette for both Chinese and Japanese Imari included underglaze blue; the Old Mobile sherds, however, contain only red and gold enamels. This palette is called “blood and milk” in the Netherlands, and although rare in the United States, Dutch museums contain many examples. One of the largest porcelain collections in Europe in the early eighteenth century—formed by Augustus the Strong, elector of Saxony and king of Poland (1670–1733), and much of which is still intact at Dresden—contains many examples.

The two fluted cups are similar but not identical; both are decorated with delicate flowers both on the exterior (fig. 1) and the interior (fig. 2). The six-sided cup (fig. 3) exhibits floral decoration on the exterior and an unidentifiable red decoration on the interior. The exterior base (fig. 4) is painted in underglaze blue with a mark inside the double ring typically found on pieces made during the Kangxi period. Unfortunately, the mark cannot be identified.[2]

The overglaze decoration on the cups is difficult to see because much of it has worn away from burial. I have provided a comparative piece (fig. 5) that is similarly decorated. The box has delicate floral decoration and fluted sides.

Linda R. Shulsky

Art historian and author

<Lshulsky@aol.com>

Linda R. Shulsky, “Chinese Porcelain in Old Mobile,” Antiques 150, no. 1 (1996): 80–89.

Linda R. Shulsky, “Chinese Porcelain at Old Mobile,” Historical Archaeology 36, no. 1 (2002): 97–104. Ceramic experts at the National Palace Museum in Beijing also were unable to identify this mark.