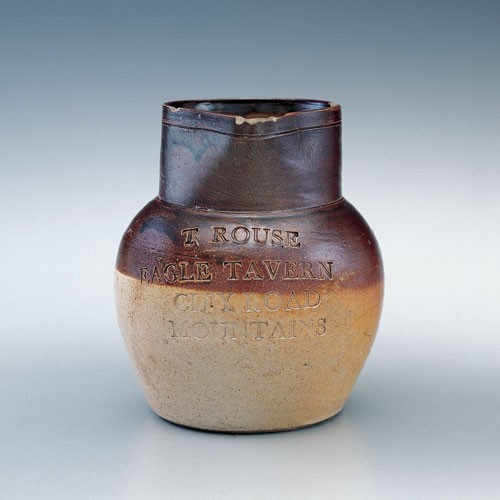

Jug, London, 1825–1850. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 5 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

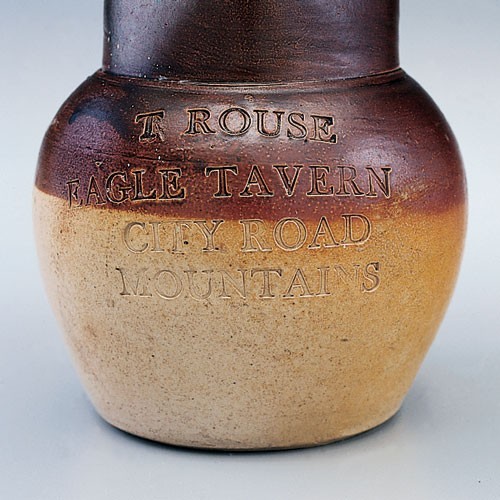

Detail of the inscription on the jug illustrated in fig. 1.

View of the Eagle Tavern, London, 2002. (Photo, Donna Ware.)

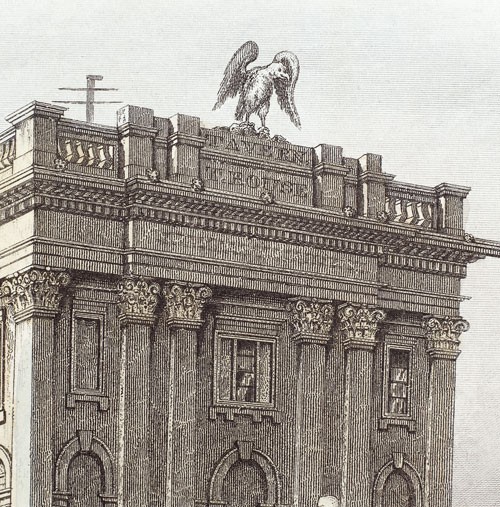

Eagle Tavern, steel line engraving on paper, John Shury (fl. 1813–1846), 1841, for Finsbury Square, City Road, publisher T. Bowyer. (Private collection.)

Detail of the engraving illustrated in fig. 4, showing the proprietor’s name, T. ROUSE, in stone on the pediment.

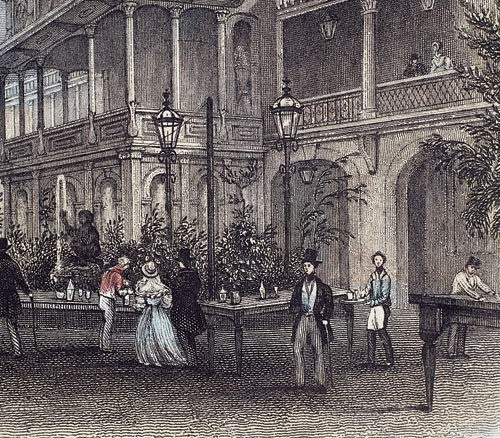

Pleasure Grounds, Eagle Tavern, City Road, steel line engraving on paper, by John Shury (fl. 1813–1846), 1841, for Finsbury Square, City Road, publisher T. Bowyer. (Private collection.)

Detail of the engraving illustrated in fig. 6 showing alcoholic beverages being served in bottles, glasses, and a small, perhaps stoneware, jug.

Archaeologists and other students of historical ceramics are accustomed to extracting a narrative of the past from simple sherds and vessels. Ivor Noël Hume, in his recent work, referenced such activity with the beseeching title If These Pots Could Talk. Although Noël Hume proves himself an admirable interrogator of ceramics, the subject of this short paper goes one better: describing a pot that can sing of its past—in nursery rhyme!

The vessel in question seems unremarkable at first glance. It is a small English brown salt-glazed jug from the second quarter of the nineteenth century, dipped in iron oxide to produce the two-tone style of stoneware that had been popular in homes and taverns for well over a century (figs. 1, 2). It is the inscription that makes the vessel remarkable. Stamped in individual letters across the front are the words:

T. ROUSE

EAGLE TAVERN

CITY ROAD

MOUNTAINS

The nursery rhyme connection derives from the fact that throughout the nineteenth century pawnshops were located just up the City Road from the Eagle Tavern, close to Angel Islington. Add to this the information that to pawn one’s watch (or coat) was once known in London slang as “popping” your “weasel,” and one can decipher the song:

Up and Down the City Road

In and Out of the Eagle

That’s the Place the Money goes

Pop goes the Weasel

The poem, of course, has many verses, and variations abound. It was first published as a dance song in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1850, but is actually much older, and obviously English in derivation.

There is still an Eagle Tavern on City Road in London (fig. 3), although the current structure was built in 1901 after a fire consumed its predecessor and is, in fact, the third of its name to stand on the spot. The date of the original structure remains unknown, but the second to bear the name—built between 1825 and 1828—is the one referred to on the jug shown here (fig. 4). This can be established readily by the fact that a Thomas Rouse was the first (and longest) proprietor of the second Eagle Tavern, running the operation from 1828 until about 1850. His name can be clearly seen in a detail of an 1841 lithograph showing the street side of the tavern (fig. 5). The word “mountains” refers to a left-leaning political party of the late eighteenth to mid-nineteenth century.[1]

Over its long history the Eagle Tavern seems to have undergone not only structural changes but also changes in social emphasis. The first building had repute both as a tea garden and as a venue for wrestling. In its 1828 incarnation it seems to have been best known for its large and popular outdoor theater (figs. 6, 7). Charles Dickens refers to this theater as the “Rotunda” in his Sketches by Boz (characters, “Miss Evans and the Eagle”) written about 1835. After 1854 it was acquired by another owner and until the 1870s was known as the Eagle’s “Grecian Theatre.”

By the late nineteenth century the area around the Eagle Tavern had fallen into a state of disrepute, perhaps due in part to its proximity to the East India Docks. In order to combat widespread public drunkenness, the Salvation Army acquired the Eagle in 1883 and operated it as a “citadel,” or rehabilitation center, until the structure burned down at the turn of the century. The Eagle Tavern apparently retained its name under the Salvation Army, however, for it is mentioned as such in articles in the London Times in 1888 concerning the murders of prostitutes by “Jack the Ripper.”

So once again a long and storied history is revealed in a simple ceramic vessel. This stoneware jug sings of its past like a haunting childhood memory. Now, if I could just get that tune out of my head. . . .

Al Luckenbach, Ph.D.

Director

The Lost Towns Archaeology Project

Anne Arundel County, Maryland

<Alluck@aol.com>

<http://www.geocities.com/londontown.geo/>

Personal communication with Ivor Noël Hume, 2003.