Gin flasks, Staffordshire, ca. 1840. Stoneware. H. of tallest: 8 5/8". (All objects from the Noël Hume collection unless otherwise noted; photography by Gavin Ashworth unless otherwise noted.) In collections of English brown stoneware gin flasks, a hump-backed hag is relatively common, but whether or not she represented Judy, wife to Mr. Punch, has been cause for prolonged speculation. Identifying Punch, himself (center), had never been an issue. Now husband and wife are unequivocally united by the paired flasks impressed with the name

and ownership of the same London Tavern (see fig. 2).

Detail of impressed marks on flasks illustrated in figure 1.

Ink bottle, Doulton, Burslem, Staffordshire, ca. 1899. Stoneware. H. 8". Doulton ink wells and bottles are a collecting field on their own. This example of a Stephens sheered-neck bottle has wider interest, serving as a reminder that diamond-shaped registry marks were applied to ceramics of all kinds across more years than the marks state. This example was registered in 1876, but the inclusion of the word LIMITED in the Doulton factory mark puts the bottle no earlier than 1899.

Detail of mark on ink bottle illustrated in figure 3.

Jug, Doulton, Burslem, Staffordshire, ca. 1911. Stoneware. H. 11 3/4". This Rhenish-type stoneware drinking vessel with 1911 silver mounts was auctioned as dating from the seventeenth century, but when Colonial Williamsburg’s master silversmith George Cloyed temporarily removed the base, its true identity was revealed.

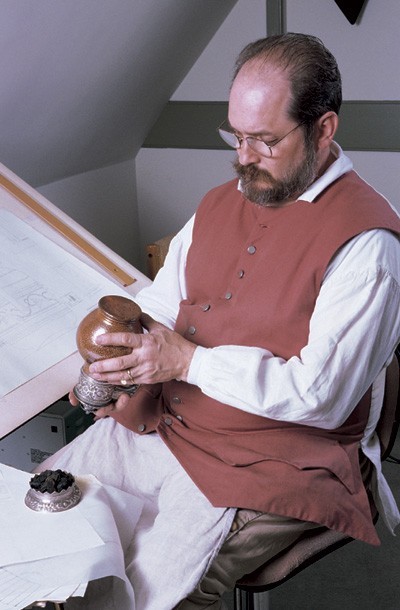

George Cloyed with the Doulton jug and removed silver base.

Detail of the revealed Doulton mark.

Jugs, Doulton, Burslem, Staffordshire, ca. 1911. Stoneware. H. of tallest: 6". Although Doulton’s fine wares have received much collector attention, the factory’s once common domestic and tavern lines have only recently begun to earn the interest they deserve. These examples made for Berkshire public house owners in 1911 illustrate the longevity of Doulton’s nineteenth-century “hunt jug” designs.

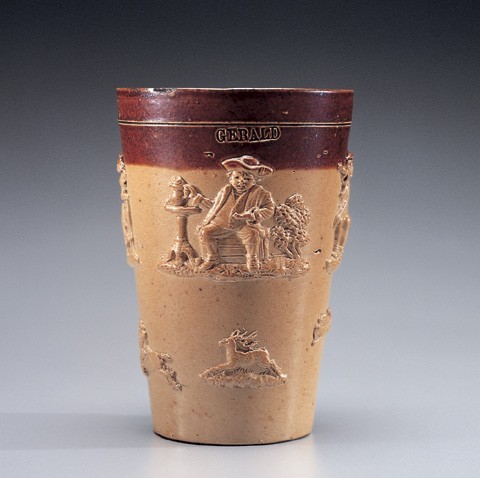

Beaker, Doulton, Burslem, Staffordshire, ca. 1880. Stoneware. H. 5 1/2". This personalized Doulton beaker has had the name impressed with individual letter dies, the “E” of which touched the wall before being applied, evidence of the continuing use of single-letter stamped inscriptions.

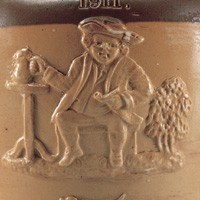

Examples of sprigged “toper” ornaments characteristic of Doulton’s Lambeth brown stonewares throughout the second half of the nineteenth century: left: the owl in the bush; center: a standard Toby Fillpot; and right: the cat-headed dog.

Examples of sprigged “toper” ornaments characteristic of Doulton’s Lambeth brown stonewares throughout the second half of the nineteenth century: left: the owl in the bush; center: a standard Toby Fillpot; and right: the cat-headed dog.

Examples of sprigged “toper” ornaments characteristic of Doulton’s Lambeth brown stonewares throughout the second half of the nineteenth century: left: the owl in the bush; center: a standard Toby Fillpot; and right: the cat-headed dog.

Bank, Samuel and Henry Bridden, Brampton, Derbyshire, 1840–1860. Stoneware. H. 3 7/8" (lacking finial). Front and back of a personalized, honey-brown stoneware money box. The purloined pig scene was thought to be a metaphor for piggy bank savings until it was discovered that the Briddens used similar molds for tobacco and butter jars. Broken off when the box was emptied, the finial may have been a sitting hen, a chimney stack, or a shell-shaped ornament.

Reverse of the bank illustrated in fig. 11.

A group of German stoneware wasters, Raeren, Germany, ca. 1550. Stoneware. H. 2 1/4". Said to have been intended to contain thread-lubricating oil to be hung around the necks of Flemish weavers, further investigation showed that these miniature costrels had many more uses.

Detail from Peter Bruegel’s The Land of Cockaigne, 1567. This engraving illustrates a mini-costrel hanging beside a pen sheath at the waist of a sleeping scholar. There can be no doubt that the little bottle contained his ink or that such was its primary use.

Ink pot, England, late sixteenth century. Earthenware. H. 1 7/8". (Courtesy, Jacqueline Pearce and the Museum of London; photo, Ivor Noël Hume.) A lead-glazed Border Ware copy of a Rhenish stoneware scriver’s ink pot.

Examples of stoneware wasters, Raeren, late sixteenth century. H. of tallest: 9". From a Raeren kiln dump illustrating pear-shaped drinking vessel profiles that rarely found their way into the export market.

Mugs, Raeren, late sixteenth century. Stoneware. H. of tallest: 4 1/8". These semi-conical mugs from a Raeren kiln dump are another type uncommon in the export trade. The difference in their bases demonstrates the fallacy of drawing stylistic conclusions from too little evidence. One mug exhibits wire pulling marks and the other the result of seating on a sanded wheel.

Bottoms of the mugs illustrated in figure 17.

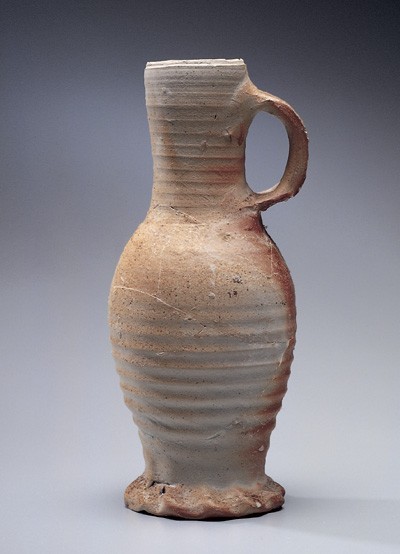

Jug, Germany, thirteenth century. Stoneware. H. 7". Collectors of Rhenish stonewares have hitherto shown little interest in the evolution of the ware through the medieval centuries. This example of Rhenish proto-stoneware, in spite of being wildly distorted and a potential waster, was reported to have been excavated in London.

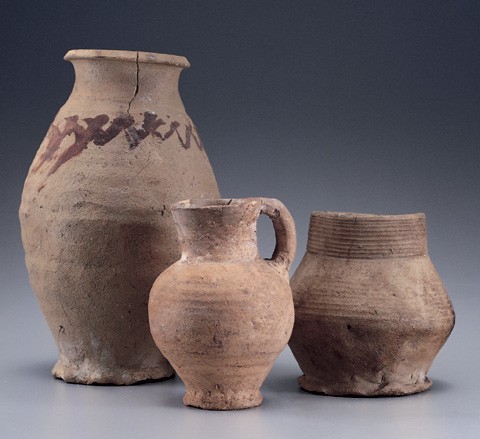

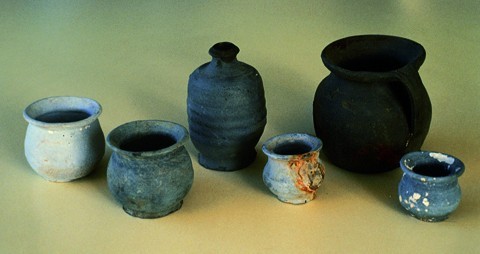

Examples of twelfth-century proto-stoneware. H. of tallest: 9 5/8". Left: from Pingsdorf painted with iron oxide; center: a pitcher in a similar ware from the Brunssum-Shinveld district of Dutch Limburg; and right: a mug of uncertain origin but attributable to the thirteenth or fourteenth century. All found in the Netherlands.

Jug, Sieburg, ca. 1400–1460. Stoneware. H. 8 3/4". Plentiful in the fifteenth century were the stonewares of Siegburg, one of whose shapes sports a curious and rarely explained name : Jacobakanne. The apocryphal association with the Countess Jacoba van Beijeren commemorates a remarkable lady around whom fairy tales could have been spun.

Examples of Normandy gray stoneware pharmaceutical pots and a bottle recovered from an unidentified shipwreck off the coast of Bermuda, ca. 1760. H. of bottle: about 3 1/2 ". (Collection of E. B. Tucker, Bermuda; photo, Ivor Noël Hume.)

Plates, Staffordshire or Yorkshire, 1775–1785. Creamware. D. 9 3/4". English creamware plates in the Royal shape decorated with an unusual version of the ubiquitous Chinese House pattern, their significance enhanced by their backs exhibiting the ghost images of two more from the same batch. Together, the four examples demonstrate the degree of painting freedom exercised between one plate and the next.

Backs of plates illustrated in figure 23. (Photo, Ivor Noël Hume.)

Backs of plates illustrated in figure 23. (Photo, Ivor Noël Hume.)

Nathaniel Bailey’s ever helpful early eighteenth-century Etymological English Dictionary defined collecting as a “gathering together or picking up,” suggesting, perhaps, that the lexicographer had garbage in mind. A hundred years earlier, essayist John Earle had described an antiquarian collector as one who “loves all things (as Dutchmen do cheese), the better for being mouldy and worm-eaten.”[1] Both Bailey and Earle would have been rendered speechless had they been told that their own cast offs, be they old clothes or kitchen crockery, would today be vied for and puzzled over by collectors.

For my part, puzzling has been the driving force; finding out being the ultimate purpose of finding. Its corollary, however, is that the need to find out implies ignorance and a willingness to be deceived. In his book The Portrait of a Scholar (1920) Robert William Chapman put it best. “A collector,” he wrote, “should not be too careful to be sure of what he buys, or the sporting spirit will atrophy.”[2] There is no denying, however, that the prospect of securing a bargain by knowing more than the seller creates an adrenaline rush matched only by its reverse when you discover to your cost that you didn’t.

As my recent book If These Pots Could Talk makes clear, my late wife and I were eclectic collectors of ceramics (and much else from armor to mummified hands) and happily gathered together a collection of the kinds of earthen and stone wares that specialist collectors of Keramics considered unworthy of cabinet space. When we began, the remains of the relatively recent past were no better respected, but over the last half century such studies have been legitimized. In America, historical archaeology is now as established a discipline as prehistory, while in England, post-medieval archaeology vies with Roman or Saxon sites for academic attention and funding. Rarely a month goes by without new information being unearthed, some of it making nonsense of old assumptions and conclusions.

Unfortunately, potentially valuable ceramic information from excavations can go unrecognized and unpublished, while much that does get into print does so in journals undiscovered by many who might profit from them. That certainly is true of older collectors unable to keep abreast of current research. Their loss is nobody else’s unless the aging collector is rash enough to publish what he believes to be sound information thereby sticking his errors to the brows of his readers like used fiypaper.

Even as my If These Pots Could Talk was in press, I discovered that I had unnecessarily devoted more than a page to debating the identification of an English stoneware gin fiask in the shape of a hump-backed woman who might or might not have been Judy, the wife of Mr. Punch. The undeniable proof was about to come under the auctioneer’s hammer—too late for me to do anything but place the winning bid. A pair of fiasks coupling the deformed woman with an equally deformed man was impressed E. M. SHEPPARD / FRENCH HORN TAVERN / CRUTCHED FRIARS. There could be no doubting the figures’ identities. More often than not, the Judy figures were unmarked, but another in my collection that is, was made for J.BROWN / Wine & Spirit Merchant / ADAM & EVE / 144 CHURCH STREET / BETHNAL GREEN (fig. 1, 2). More on these marks anon.

Perhaps because earlier English stonewares are increasingly hard to find, interest in once common nineteenth-century wares has greatly expanded. One might suppose that examples scarcely 150 years old would retain few secrets worth pursuing. Makers’ marks are common and attributions carved in stone—or are they?

Why, for example, does a Doulton of Lambeth ink bottle carry an impressed “21” that some collectors have believed to indicate the year of manufacture as 1921, and alongside it a registry letter for 1876 using the diamond-shaped combination that ceased to be used after 1879 (fig. 3, 4)? Royal Doulton historian Louise Irvine has pricked the dating bubble saying that the numbers within Doulton’s oval mark are “some sort of reference number for the bottle, although it is not known exactly what it signifies.”[3] She has added that the oval inscription reading DOULTON & CO. LIMITED / LAMBETH postdates 1899 when Doulton became a limited company. Clearly, therefore, the 1876 registry mark was being used long after its accepted three-year expiration date. The registration had been filed by Doulton in 1876 on behalf of the famed ink manufacturer Henry Stephens of Aldersgate, London, who had designed this sheered neck and lipped bottle that would be made in fifteen different sizes.[4]

Another of my pot book’s half truths provided grist for an illustrated essay explaining why a silver-gilt mounted brown stoneware mug (or jug?) was not German of the seventeenth century as the auction catalog had stated.[5] There is no need here to review all the reasoning leading to the conclusion that the mug was really made by Doulton around 1910. Suffice it to say that I was convinced that it was as recent as its mounts which bore a Chester date letter for 1911 and the mark for silversmiths G. Nathan and R. Hayes. However, that posed another problem. Why would a reproduction made by Doulton at Lambeth be shipped to a Chester silversmith to be finished?

With the question still unanswered my book went to press. Shortly thereafter another identical mug was brought to auction at Christie’s, but this time with no seventeenth-century attribution (fig. 5).[6] The mounts’ decoration was the same save for its Chester hallmarks for 1912. So here were two mugs, both with Chester mounts—yet apparently shipped all the way from London’s Lambeth. It would make much better sense, I thought, for the pots to have been made about thirty miles away in Burslem. Although Doulton had begun purchasing Staffordshire factories in 1877, the standard books did not indicate that brown stonewares were among its products.[7]

Commenting on the then still-unsolved mystery, Ms. Irvine noted that “around 1910, Doulton artists Harry Simon and Francis Pope modeled a range of shapes inspired by early Rhenish stoneware and these were salt-glazed to recreate the distinctive ‘orange skin’ texture of the 16th century.” Quoting previous Doulton historian Desmond Eyles, she added that “The mottled surfaces recall the Rhineland stoneware used by Elizabethan silversmiths as a foil for silver and silver gilt mounts.”

Were it not that a leading expert on German stonewares remained reluctant to accept this Doulton evidence without unequivocal proof, I would have been content to go along with the Doulton attribution. But thus challenged, I decided that the only means of providing the proof would be to have the base mount removed to see whether or not it concealed Doulton marks. That delicate task was performed by Colonial Williamsburg’s master silversmith George Cloyed who found the base packed with pitch, but which, after careful separation, revealed an impressed Royal Doulton mark and the number 796 (fig. 6, 7).[8]

Among other carved-in-stone verities is the knowledge that around 1750 personalized English brown stoneware tankards, bottles, and pitchers ceased to be scratch-inscribed and that thereafter printers’ type was substituted. But what is meant by thereafter and how did it differ from the hereafter’s evermore? While pondering that, we may also pause to ask at what point did Toby Fillpott and a supporting cast of rustic topers begin to substitute for the earlier sprig-applied trees, houses, convivial panels, and the signs of taverns and shields of craft-related companies?

The answer to these questions is around 1800,[9] although the applied stag-chasing scenes characteristic of the eighteenth-century “Hunting Jugs” persisted throughout the nineteenth century, and indeed, into the twentieth.[10] The combined design’s longevity is demonstrated by two pitchers of graduated sizes bearing the mark DOULTON & CO. / LIMITED / LAMBETH, both with type-impressed identifications as having been made for Mr & Mrs J. Reddick / Old Windsor / 1911 (fig. 8).[11]

The spacing of the lettering on both the Reddick pitchers is identical, strongly indicating that the type was set in blocks and thereby applied as one. But had this always been the method of applying type-impressed names of people and places? It certainly was true of initialed seals applied to glass wine bottles of the second half of the seventeenth century.[12] Eccentricity of alignment is not in itself proof of one-letter-at-a-time application. To be sure of that, one needs two examples of one inscription, both applied at approximately the same time. The previously discussed Punch and Judy fiasks provided such an opportunity and left no doubt that the letter dies were individually applied. Another example is provided by a beer beaker marked *DOULTON*/ LAMBETH and impressed below the rim with the name GERALD (fig. 9).[13] The same “A” die had been impressed on the base and the “E” had touched the upper wall while being moved into place.

Such beakers were being made by Doulton in the 1870s providing a terminus post quem for the transition from separate letters to inscription-impressing blocks.

In their book English Brown Stoneware 1670–1900, the late Adrian Oswald and Robin Hildyard began a partial analysis of sprig ornamentation on hunting jugs and mugs, but limited their illustrations to windmills, trees, and handle terminals.[14] Much more remains to be done. Among devices characteristic of the late Doulton wares, for example, are a barrel-seated toper with a cat-eared dog beside him, and on the other side of the vessel, a sprig usually paired with a snoozing sot curiously accompanied by an owl in the bush behind him (fig. 10). Both are present on the 1911 Reddick pitchers and go back at least to the 1870s. An assessment of the use and iconography of the Toby Fillpott sprig has been begun by Massachusetts collector Nicholas Johnson, and it is to be hoped that he will expand his studies to embrace the hat waver, the sleeping toper, the homeward reveler, and many other once familiar brown stoneware images.[15]

Although, for me, looking beyond the pots in search of connections to the social history of their time is the most rewarding part of collecting, the quest can all too easily lead to wrong conclusions. Mercifully not voiced in print, my great “piggy-bank” revelation was another of them.[16]Discovering that on eBay an Australian dealer was auctioning a brown stoneware box cast with a panel showing a boy stealing a pig, I saw in it an allegorical warning that one’s savings (the pig) should be kept in a place safe from plunderers (fig. 11, 12).

Made in the honey-colored brown stoneware characteristic of Brampton in Yorkshire, the box is impressed on the base S & H BRIDDON, a mark used ca. 1840–1860.[17] Stamped in single-letter type around the money-box’s shoulder is the name of its owner MARY SUSANNA DODD. Presumably it was she who broke off the finial to extract her loot.[18] Cast in two parts, the lower wall is relief-decorated on one side with a smoking toper and somebody who strongly resembles the previously mentioned “befriended owl” pose (albeit sans owl) and on the other with a lively scene showing a boy stealing a piglet and being pursued by the sow while watched by an assortment of yokels. It seemed to me that this rustic drama was allegorically related to the idea of keeping one’s money safe from theft—thereby a mid-nineteenth century manifestation of the American piggy bank. I subsequently discovered, however, that Samuel and Henry Briddon used the same mold to make tobacco jars whose upper element became the removable lid.[19] No amount of allegorical legerdemain could link tobacco and purloined piglets.

The mold used to create the money box was old, and the details of the scene consequently eroded. One can barely see, for example, that along with the two male observers, a women holding a child stands by the gate to the right of the scene. Nor can one see that the gate is open. But on examining more crisply molded Briddon examples, it is evident that only the sow sees the event as larcenous, the people having instructed the boy to bring home the bacon.[20] The Aesopian moral to this story is simply stated: reading much into little is an exercise best kept private. It is equally true that in the study of stonewares a little knowledge is rarely enough. A case in point: Another eBay auction yielded a group of five very small jugs or costrels, all wasters from a stoneware kiln dump at Raeren (fig. 13). Their necks were consistent with a mid sixteenth-century date, but their little ear-like handles were unlike any I had seen. Their capacities being inconsistent, they could not be measured. So what were they?

A friend wise in stoneware matters promptly provided an answer: “I know exactly what they were for,” he assured me. They were used by Flemish weavers as containers for thread lubricants and were hung on strings around the workers’ necks. When asked for documentation, my friend referred me to a London dealer who said he obtained the information from another dealer in Holland who informed him that the mini-costrels were often seen in European paintings—but failed to be specific. Nevertheless, I was now in a position to respond with self-satisfied authority if asked how the pots were used. Although the question was unlikely to be asked with any frequency, I thought it best to seek a Netherlandish weaver illustration of my own.

I failed to find one, but somewhat disconcertingly, I came up with several engravings by Peter Bruegel the Elder showing what appeared to be squatting scholars with little blobs dangling by strings from their belts. Another Bruegel engraving showed the blob hanging from the side of a basket containing books. It seemed reasonable to deduce, therefore, that Bruegel’s blobs were actually personal ink pots.[21] More clearly depicted, however, was his engraving titled The Land of Cockaigne, depicting three slumbering loafers: soldier, laborer, and clerk, the last with open quill case and ink pot hanging at his side (fig. 14).[22]

It was David Gaimster who pointed me in yet another direction. In an article titled “Oil Pot or What?”, Ian Reed of Trondheim in Norway cited several instances where these little bottles had been found buried in churches and other Norwegian religious buildings, each pot containing small fragments of bone, and in one instance with a sealed piece of parchment identifying it as a reliquary dating to the year 1476.[23] In sum, therefore, it would seem that these small costrel-style pots were made for several purposes and were exported from Raeren to Scandinavian countries rather than to England.[24]

But even that assumption may be false. In her seminal publication Border Wares, Jacqueline Pearce illustrated another of these scriveners’ pots, this one having been found in London (fig. 15).[25] Puzzled as I was when I first saw them, she concluded that “it could hardly have been intended for practical use and may well have been a toy.” Ms. Pearce added that it was brown glazed and “unknown in the standard form.” But having since examined this tiny pot, I have no doubt that Ms. Pearce is correct in attributing it to a Border Ware kiln and to a date in the late sixteenth century.[26]

The persistent probing or looting of Rhenish kiln dumps is no less an archaeological hot potato than is shipwreck salvage, but the resulting availability of the factories’ more mundane wares has served to generate student and collector interest in an aspect of the industry that has hitherto merited little extra-European attention. Just as decorative arts museums have concentrated on masterpieces and have deliberately avoided the second rate, thereby creating a false impression of the average individual’s possessions, so the survival of relief-decorated German stonewares has left us oblivious to the run-of-the-mill wares that were staples of the industry in the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries.

We tend to think of Rhenish mugs (or drinking jugs) being gray in the first half of the sixteenth century and iron-washed brown in the later years. Kiln wasters demonstrate that both were in production toward the century’s end, and that the late wares were more elegant than their predecessors and were sometimes carefully cordoned at their necks to emphasize the simplicity of their profiles (fig. 16). Having no claims to beauty, but also coming from Raeren kiln dumps, is a class of small mugs or cans, slightly conical in shape and markedly ribbed (fig. 17,18). Tapering mugs with and without applied decoration are relatively well known, but these two differ in that their walls are offset above pad-like bases—bases which themselves differ one from the other.[27] That on the left exhibits the wire pulling marks common to most Rhenish stonewares, but its companion had been stood in sand on the wheel and was therefore left with what might be described as a rusticated bottom. I confess that in publishing the latter mug, I had suggested the possibility that if it was not a Raeren product, it might have come from a lesser known factory such as that at Bouffioulx in Belgium.[28] When, however, the second mug turned up to parallel every construction detail but the sandy bottom, the “obscure kiln” theory collapsed. So did any thought that there might be a dating difference between gray and brown. Another example, one sufficiently distorted in firing that it should have been discarded as a waster, has been dredged from the River Wensum near Norwich, leaving us to wonder at the craftsmen’s lack of pride in their work.[29] The possibility exists, of course, that this warped mug was not deliberately exported, but was lost overboard from a visiting Dutch trading or fishing vessel.

Not as easily dismissed, however, is a much earlier Rhenish proto-stoneware jug reputed to have been found in London (fig. 19). Though severely distorted in firing, this is a type well known in the Low Countries in the mid-thirteenth century.[30] Exhibited in a museum case alongside perfect examples of medieval pottery, this stoneware jug cuts a pretty sorry figure. However, in many ways it is infinitely more interesting—if only in that it raises questions worth asking. When it emerged spoiled from the kiln, who made the decision not to toss it onto the waster heap? Was it sold at a cut price to some poor soul who could not afford a better jug? Or was it cynically exported in the belief that the undiscerning English would buy anything they could get? And what was going on in London at the time the jug arrived?[31]

This we do know: Henry III was on the throne. His French marriage encouraged French emigration into the city which was resented by its inhabitants. The king’s self-serving relationship with Rome and his approval of his brother Richard to stand for election as Holy Roman Emperor led to civil war after Richard proposed turning over a third of the country’s revenue to the Pope. London merchants joined with country nobles to oppose the king, and the resulting popular rebellion led by Simon de Montford ended with the capture of the king at the Battle of Lewes in 1265. In short, these were uncertain and dangerous times, jug pourers not knowing from one week to the next what calamity might disrupt their lives. This, of course, is not the page to embark on a history of thirteenth-century England. My point is simply that when one studies the Rhenish jug, a door opens—just a little—to the life and times of the people who made, transported, and used it.

To collectors of German stonewares whose interests focus on the great relief-decorated vases and jugs from Raeren (and subsequently from the Westerwald) in the late sixteenth century, the notion that the industry’s history began centuries earlier is often of small concern. If it isn’t decorated and shiny it has no place in a collection of ceramic art, they say. But what about collections of ceramic history? To better appreciate the best, surely it is necessary to climb the ladders that lead up to it? Thus, for example, the story of Germanic stonewares began in the late twelfth century at centers with odd sounding names like Brühl-Pingsdorf and Brussum-Shinveld where the development of increasingly hard and liquid-impervious fabrics would lead to the more smooth-surfaced wares that became the trademark of Siegburg stoneware in the fifteenth century (fig. 20). I would argue that a teaching collection is incomplete without a leavening of such early wares, no matter how unappealing they may be to the connoisseur.

When writing about or cataloging post-medieval and earlier ceramics, the problem of acceptable and correct nomenclature is ever present. We see it, for example, in the ubiquitous mask-decorated German bottles of the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. Every collector is now aware that associating them with Cardinal Roberto Bellarmino is a mistake. But in spite of revisionist writers (myself included) who prefer the German Bartmankrug or the English Graybeard, dealers and auction houses continue to call them Bellarmines. Another popularly used German term is Jacobakanne to describe the tall-necked stoneware drinking vessels from Siegburg common in the fifteenth century (fig. 21). But who was Jacoba and why did she give her name to a jug? Dutch collector Marco Maas has provided an answer.

The four-times married Countess Jacoba van Beijeren (also known as Jaqueline of Holland) was born in 1401 and was first married when she was six years old. Her tempestuous life included imprisonment in the castle at Ghent in Flanders, where she passed the time making pottery which she tossed into the moat after each piece was finished. When, in the eighteenth century, examples of the tall Siegburg pots were dredged out of the moat, they were hailed as the products of Jacoba’s hobby.[32]Ludicrous though it is to accept that the incarcerated countess was firing stoneware in her prison cell, the name has stuck simply because it serves to identify a particular shape. It also provides a springboard for the romantically inclined to dig deeper into the life of the reputedly beautiful young woman who married the Dauphin of France, her cousin the Duke of Brabant, the Duke of Gloucester, and trigamously Frans van Borsselen, Lord of the province of Zeeland. But back to pots.

The lesser known and under-appreciated Rhineland stonewares were matched in Normandy where, in the mid-eighteenth century, kilns at Martincamp and elsewhere were competing with those of their northern neighbors.[33] Much of what we know about these wares comes from French Canada, specifically at Louisbourg (1713–1758), and from a shipwreck off the coast of Bermuda known (for want of specific documentation) as “The Frenchman” that sank around 1760 (fig. 22).

From the latter came strap-handled pitchers similar to others from Louisbourg as well as a series of gray-bodied and unglazed pharmaceutical ointment pots in several sizes, and a small bottle in the same ware recovered still corked, the latter containing an unidentified oil.[34] I know of no published examples of such pots and bottles being found in England, but it is entirely possible that if and when fragments have been unearthed, they have gone unidentified and therefore ignored.

As long as there have been druggists there has been a need for pots wherein to pack their potions. Although, in studying the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries we tend to think of drug pots and jars as having been the monopoly of delftware potters, in reality they were made in every available ware from lead-glazed Staffordshire earthenwares to creamware and white salt-glazed stoneware. Recently reported excavations at the site of a circa 1774–1787 stoneware manufactory near Trenton, New Jersey, have yielded several examples.[35] Described by project director Richard Hunter as “condiment pots,” they nevertheless derived their shape from contemporary delftware pharmaceutical containers.

Now for something entirely different.

In If These Pots Could Talk, I illustrated a creamware plate that had been sold cheaply because, as the dealer explained, “it was dirty on the back.”[36] The dirt proved to be a ghost impression of the cobalt-painted “Long Eliza” pattern from the next biscuit plate in the stack. I described this manifestation as a “rare demonstration,” and nobody came forward to say otherwise—until I did so myself.

I was to find not one, but two matching Royal pattern creamware plates in a rural Virginia antique shop, both dirty on their backs (fig. 23, 24). There could be little doubt that they came from the same prematurely stacked batch and had miraculously remained together for more than two hundred years. The backs of each exhibited ghost images of the design my late wife and I had facetiously dubbed the “Chinese TV house pattern,” but neither exactly matched the fronts.[37] It was evident, therefore, that several more “wet ones” had been part of the batch and that the newly acquired plates had not been stacked directly one on top of the other. Nevertheless, they provide documentary evidence of the scope of a single painting session for one design.

In the first volume of Ceramics in America (2001), ceramic historians George Miller and Robert Hunter provided a pioneering assessment of the development of “china glaze” earthenware (pearlware) and in the process demonstrated the enormous diversity of designs based on the so-called pagoda and Long Eliza themes. The same year saw the publication of Lois Roberts’ paper “Blue Painted Creamware and Pearlwares” which, for the first time, attempted to analyze and attribute individual elements in the pagoda pattern.[38] Significantly, perhaps, the newly found pair of Royal pattern creamware plates is paralleled by none of the examples illustrated or discussed by either Miller and Hunter or Roberts. Instead, the design includes details of its own, notably the tall chimneys at front and back of the house, and the crosses at the junctions of the fianking fence lattices.[39]

Minor differences, notably in the foreground rocks and fiights of birds, might suggest that more than one painter was involved in decorating these four house designs, and that rather than viewing the leisurely work of a single happy paintress, one is seeing the products of sweatshop mass-production that had short-circuited the drying process.

Be they brown stone gin fiasks, mystery jugs, squashed mugs, or dirty-bottomed creamwares, these widely disparate specimens are yet more examples of the intellectual fun to be derived from pursuing the people behind the pots.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author is indebted to British Museum curator David Gaimster, dealer Garry Atkins in London, Doulton historian Louise Irvine, collector Marco Maas in Holland, Jacqueline Pearce at the Museum of London, stoneware collector Nicholas Johnson, ceramic historian George Miller, Colonial Williamsburg’s master silversmiths James Curtis and George Cloyed, and friend and scholar Robert Hunter of the Chipstone Foundation for their willingness to share their skill and answer dumb questions

John Earle, Microcosmographie or A Piece of the World Discovered in Essays and Characters (London, 1628) as quoted by Ronald Jessup, Curiosities of British Archaeology (London: Butterworth, 1961), p. 10.

Chapman added that “he who collects that he may have the best collection, or a better than his friend’s, is little more than a miser.”

Louise Irvine to Ivor Noël Hume, personal communication, January 20, 2002.

Colin Roberts, Doulton Ink Wares (London: Bee Publications, 1993), pp. 109–11.

See also “Potsherds and Pragmatism: One Collector’s Perspective,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 16–17.

Christie’s, London, September 25, 2001, Sale no. 9199, lot 18.

Doulton began manufacturing stoneware drain pipes at Rowley-Regis near Birmingham before 1877. At Lambeth, Henry Doulton had opened a ceramic pipe factory in 1846. The company’s history by Desmond Eyles, The Story of Royal Doulton 1815–1965 (London: Hutchinson, 1965), p. 15, notes that “If Henry Doulton had never done anything else but help to pioneer the general use of stoneware drainpipes he would have earned a secure place in the social history of the Victorian era.” Doulton’s fine ware production began at Burslem around 1882.

The standard lion-topped crown over the Royal Doulton roundel was in general use between 1902 and 1922. Jeffrey A. Godden, Encyclopaedia of British Pottery and Porcelain Marks (New York: Crown Publishers, 1964), p. 215.

Robin Hildyard, Browne Muggs, English Brown Stoneware (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1985), p. 80, nos. 204, 205.

Messrs. Doulton and Watts in their 1873 price list offered “Hunting Jugs (Common clay)” in capacities from 1/4 pint to 1 gallon, as well as in “Fine Clay”; Chris Green, John Dwight’s Fulham Pottery, Excavations 1971–79 (London: English Heritage, 1999), p. 367.

Old Windsor is a Berkshire village and parish on the River Thames two miles south east of Windsor.

Ivor Noël Hume, “A Seventeenth-Century Virginian’s Seal: Detective Story In Glass,” Antiques 72, no. 3 (September 1957): 244–45.

This Doulton mark began to be used ca. 1858.

Adrian Oswald, R.J.C. Hildyard, and R. G. Hughes, English Brown Stoneware 1670–1900 (London: Faber & Faber, 1982).

Nicholas Johnson, “The Man in the Middle: Toby Fillpott as a Sprig on Brown Stoneware,” The Web of Time 4, no. 2 (Internet history magazine <www.theweboftime.com>).

Ivor Noël Hume, If These Pots Could Talk: Collecting 2,000 Years of British Household Pottery (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), p. 424, note 15, cites references demonstrating that in England money boxes in the shape of pigs go back at least to the fifteenth century. According to Webster’s Ninth Collegiate Dictionary, however, in American usage the term “piggy bank” was first applied to money boxes as recently as 1941. The Oxford English Dictionary, on the other hand, leaves no doubt that as early as ca. 1440 the word “pig” was applied to any earthenware pot that lacked any other more specific name. That dictionary does not list “piggy bank” among its definitions.

Samuel Briddon was in the stoneware business at Brampton as early as 1834, continuing a tradition established by William Briddon in 1790 (Oswald et al., English Brown Stoneware, p. 164). That source associates Samuel with William Briddon at the Walton Pottery along with the S & H Briddon mark and dates it to ca. 1840–1860. On the other hand, Derek Askey, Stoneware Bottles from Bellarmines to Ginger Beer 1500–1949 (Brighton, U.K.: Bowman Graphics, 1981), p. 164, has Samuel and Henry at an independent factory in 1848 that would be purchased in 1881 to become part of the Barker factory. However, Llewellynn Jewitt, The History of Ceramics Art in Great Britain, 2 vols. (New York: Scribner, Welford, and Armstrong, 1878), 2: 122 had Henry Briddon owning the Barker Pottery prior to 1878, and makes no mention of a partnership between him and Samuel Briddon. Yet another S & H Briddon pig-decorated tobacco jar is in the Glaisher Collection at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, there cataloged as a “box with Lid” and erroneously attributed to the “Late 19th century.” Bernard Rackham, Catalogue of the Glaisher Collection, 2 vols. (Cambridge, Eng.: The University Press, 1935), 1: 162, no. 1254 (not illustrated).

Robin Hildyard, Browne Muggs, p. 113, no. 326, ca. 1840. Finials for Brampton tobacco-jars with pig panels came both in the form of a fleur-de-lis or a bricked chimney stack, and so there is no way of knowing which was used on the illustrated money box. It seems possible that tobacco jars had smoke stacks finials and that versions intended for other purposes did not.

One might expect that the two parts of the Briddon money box would have been luted together while in their leather hard state. It appears, however, that they were not joined until after their salt-glazed firing—and then with glue.

That phrase is not in the O.E.D., but “to save one’s bacon” was in use by 1691.

H. Arthur Klein, Graphic Worlds of Peter Bruegel the Elder (New York: Dover Publications, 1963). “Temperance” (1560), no. 54; “The Ass at School” (1557), no. 30.

Ibid., (1567), no. 32.

Ian Reed in Medieval Ceramics 16 (1992): 71–72 and p. 69, pl. 2.

John Hurst, David S. Neal, and H.J.E. van Beuningen, Pottery Produced and Traded in North-West Europe, 1350–1650 (Holland: Museum of Boymans-van Beuningen, 1986), pp. 197–98, no. 308, illustrate an example found at Raeren-Born in Belgium, its exterior glaze a mottled brown with gray patches, and attributed to the sixteenth century.

Jacqueline Pearce, Border Wares (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1992), pp. 32, 66; fig. 37, no. 288.

These pots being so small and virtually unbreakable, it is surprising that others have not been reported from English archaeological contexts.

H.J.E. van Beuningen, verdraaid goed gedraaid (Rotterdam: Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, 1973), pp. 49–50, no. 287, second half of sixteenth century. Also Hurst, Neal, and van Beuningen, Pottery Produced and Traded in North-West Europe, p. 199, nos. 310–12, ca. 1575–1600.

Hume, If These Pots Could Talk, p. 97, fig. V.3.c.

Sarah Jennings et al., Eighteen Centuries of Pottery from Norwich, East Anglian Archaeology Report No. 13, Norfolk Museums Service, 1981, pp. 113–14, no. 760. Described as “Dark grey fabric; shiny brown glaze on all surfaces.” No mention is made of basal markings.

Gisela Reineking-von Bock, Steinzeug (Cologne: Cologne State Museum, 1971), no. 85, n.p.; found at Cologne.

E. M. Ch.F. Klijn’s Lead-glazed Earthenwares in The Netherlands (Arnhem: Nederlands Openluchtmuseum, 1995), p. 27, noted: “The material’s value was even so high that the potters of the Middle Ages sometimes tried to mend a waster, so that, after a necessary second firing, it was serviceable again and ready to be sold.”

It surely must be a coincidence that a fifteenth-century playing card illustrated in David Gaimster’s German Stoneware 1200–1900 (London: British Museum Press, 1997), pl. 2.1, depicts a woman making Siegburg pots! Nevertheless, the citation allows me to make a correction to If These Pots Could Talk (p. 99, fig. V.5) wherein I illustrated the card and associated it with an example in the collection that I attributed to Siegburg when it should have been to Raeren.

North Normandy lies at the southern extremity of the Rhineland stoneware industry, its industrial and pharmaceutical wares reaching America by 1585. Ivor Noël Hume, The Virginia Adventure (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994), p.76.

Ivor Noël Hume, Shipwreck! History from the Bermuda Reefs (Hamilton, Bermuda: Capstan Publications, 1995), p.22.

Richard Hunter, “Eighteenth-Century Stoneware Kiln of William Richards Found on the Lamberton Waterfront, Trenton, New Jersey,” in Ceramics in America (2001), ed. Robert Hunter, pp. 238–43.

Hume, If These Pots Could Talk, pp. 221–22, fig. X.1.

Most authorities refer to the central structures as pagodas, a term defined in Webster as “a Far Eastern tower usu. with roofs curving upward at the division of each of several stories and erected as a temple or memorial,” a description far removed from a single-story hut with two chimneys.

Northern Ceramic Society Journal 18 (2001): 1–37.

There are small differences between the footrings of these plates, one being sharper than the other. But rather than pointing to diagnostically significant variations, they are a further reminder of the fallacy of reading much into little.