National Park Service technicians assembling ceramics recovered from Jamestown, Virginia, with some of the May-Hartwell collection in the foreground, 1938. (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park. Photo # 7030.)

Postcard, ca. 1938. This early souvenir postcard from Jamestown illustrates sgraffito slipware vessels from the May-Hartwell ditch. (Private collection.)

A collection of small plates from the May-Hartwell ditch. Sgraffito decorated with a variety of floral and geometric motifs. (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Clockwise from bottom: COLO J 7343; COLO J 7371; COLO J 7341; COLO J 7298; COLO J 7372.

Detail of map depicting the North Devon region in southwestern England. Sgraffito-decorated slipware was produced in the region from the seventeenth until the nineteenth centuries, most notably in Barnstaple and Bideford. (Chipstone Foundation.)

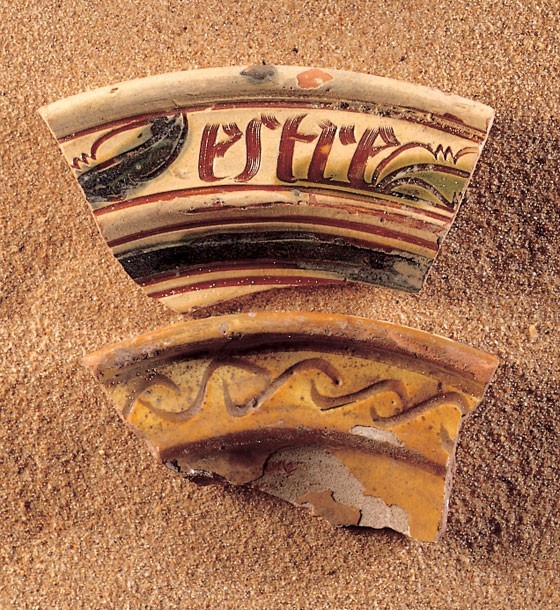

Sgraffito-decorated slipware dish fragments showing Continental influence on North Devon. Top: Beauvais, France, sixteenth century; bottom: North Devon, ca. 1620–1660. (Courtesy, Ivor Noël Hume.)

Harvest jug, North Devon, Barnstable, 1764. Sgraffito slipware. H. 14 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) This highly ornamented vessel is typical of scratch-decorated forms produced in the eighteenth century and later.

Dish, North Devon, ca. 1620–1640. Sgraffito slipware. (Courtesy, Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Excavated from the Richard Buck site near Jamestown, this example is decorated with an S-scroll rim device and a bird and leaf central motif. This decoration is commonly found on North Devon slipware from the second quarter of the seventeenth-century Virginia sites.

Detail of a carved box, England, 1671. Oak. H. 8 3/4", W. 26", D. 16 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The stylized geometric and foliage decoration on this box are elements shared in other decorative arts of the period.

Detail of a North Devon sgraffito slipware fragment illustrating that the same multi-pointed tool was used to incise parallel lines and to punch patterns of indentations on individual vessels. In this case, the tool had five points or prongs. The glaze is missing in several areas on this example. (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dish, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Sgraffito slipware. D. 13". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) COLO J 7367.

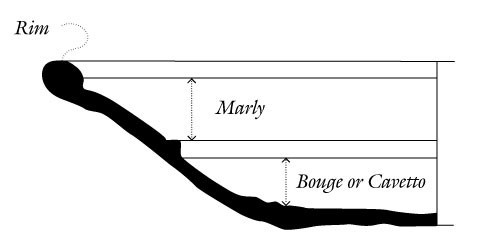

Section drawing depicting North Devon slipware dish and plate nomenclature.

Reverse of dish, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Sgraffito slipware. D. 14". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) COLO J 7354. Note the knife trimming on walls above the base, and the numerous drips of slip and glaze indicating the importance of production speed.

Dish, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Sgraffito slipware. D. 12 1/2". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) COLO J 7339. This dish is decorated with an elaborate floral motif on the marly and in the center.

Dish fragments displaying a variety of marly decorations, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Sgraffito slipware. (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Bottom to top, left to right: COLO J 53725; COLO J 53639; COLO J 53707; COLO J 53794; COLO J 53797; COLO J 53570.

Dish, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Sgraffito slipware. D. 12". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) COLO J 7330. Note swag and tassel motif on marly.

Dish, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Sgraffito slipware. D. 12 1/2". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) COLO J 7581. A floral spray on the bouge encircles the small floral medallion in the center of this dish.

Dish fragments inscribed with grape clusters, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Sgraffito slipware. (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) COLO J53475; COLO J 53481; COLO J 53495.

Dish, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Sgraffito slipware. D. 11 1/2". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) COLO J 7336. This is the only marly decorated with a chevron motif. It resembles a dish with a cross-hatched design recovered from a ca. 1673 context during excavations at Colony of Avalon at Ferryland, Newfoundland.

Dish, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Sgraffito slipware. D. 14 3/4". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) COLO J 7348. This dish is centrally decorated with a stylized so-called “Chinese butterfly” motif.

Dish, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Sgraffito slipware. D. 20". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) COLO J 7329. A compass was used to draw the six-pointed star in the center of this dish.

Dish, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Sgraffito slipware. D. 15". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) COLO J 7366. Pre-glost firing damage is displayed in the center of this plate

Plate, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Sgraffito slipware. D. 7 1/2". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) COLO J 7298.

Plate, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Sgraffito slipware. D. 7 1/2". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) COLO J 7371.

Plate, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Sgraffito slipware. D. 7 1/2". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) COLO J 7372.

Plate with piecrust edge, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Sgraffito slipware. D. 9 1/2". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) COLO J 7353. Four large carnations with bisecting stems decorate this vessel.

Detail of plate illustrated in fig. 25

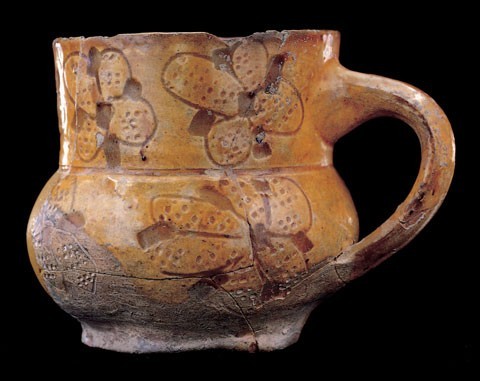

Mug, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Sgraffito slipware. H. 3 3/4". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) COLO J 47307. This gorge-shaped mug is decorated with a floral motif.

Mug, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Sgraffito slipware. H. 3 3/4". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) COLO J 7534.

Mug, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Sgraffito slipware. H. 3 3/4". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) COLO J 7297. This stylized quatrefoil flower is found on many other hollow and flat forms.

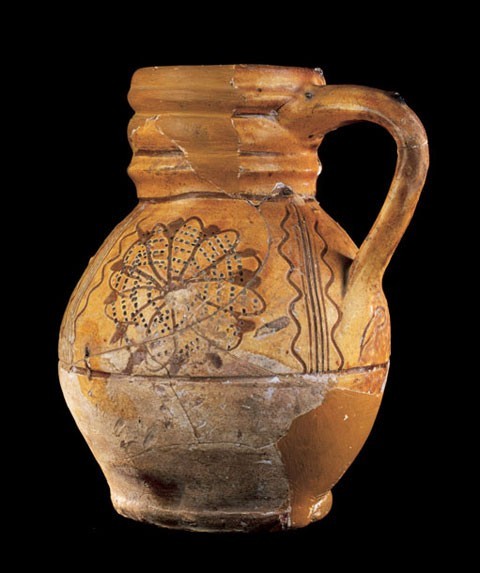

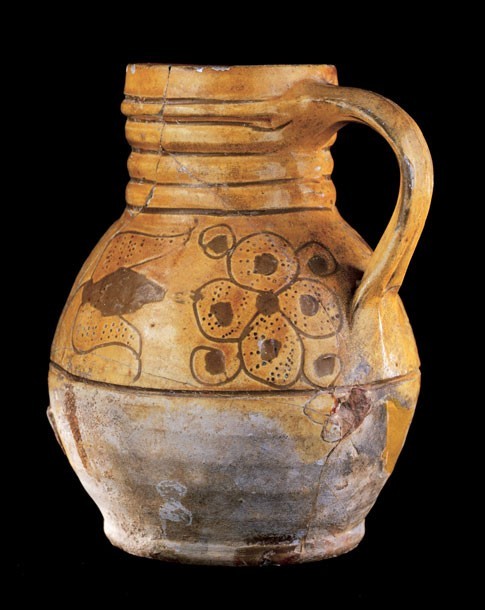

Jug, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Sgraffito slipware. H. 6 3/4". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) COLO J 7346. A combination of wavy lines and multipetaled floral devices decorate this example.

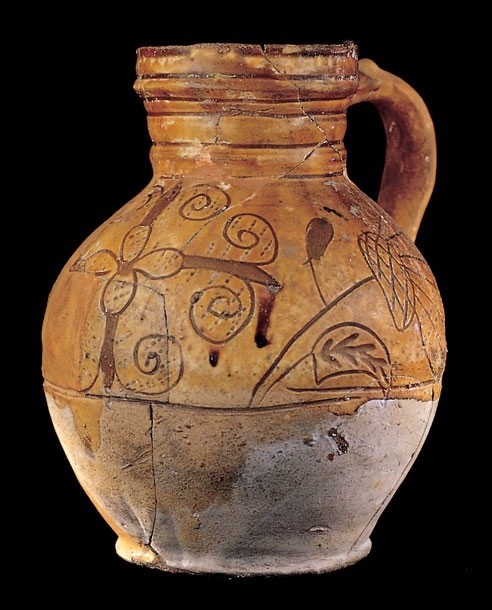

Jug, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Sgraffito slipware. H. 6 3/4". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) COLO J 7296. Quatrefoil flowers and tulips are incised on this jug.

Jug, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Sgraffito slipware. H. 6 3/4". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) COLO J 7347. This jug is ornamented with a quatrefoil flower and carnations.

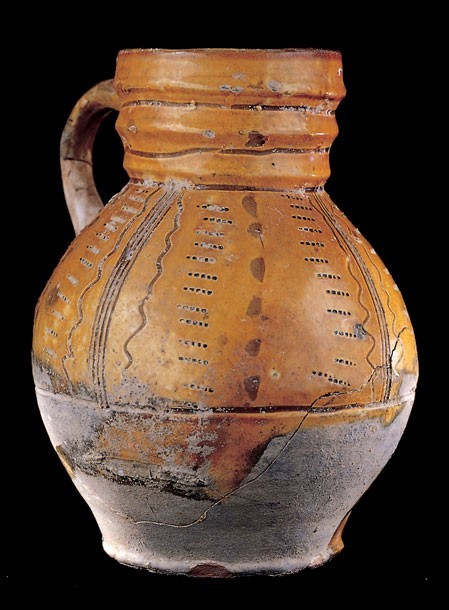

Jug, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Sgraffito slipware. H. 8 1/2". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) COLO J 7368.

Bowls, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Sgraffito slipware. H. 4", D. 8 3/4". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Left: COLO J 7352; right: COLO J 7344. Both have a single horizontal loop handle on the rim exterior, and are sgraffito-decorated on the interior

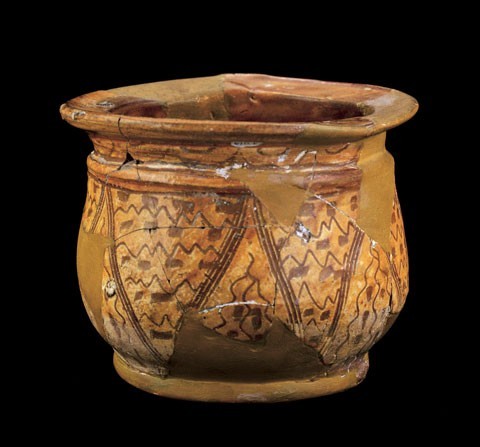

Chamber pot, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Sgraffito slipware. H. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) COLO J 7369. The exterior of this chamber pot is decorated with chevrons, wavy lines, and dashes.

Fragments of two incomplete chamber pots, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Sgraffito slipware. (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth). COLO J 53452; COLO J 53459; COLO J 53469; COLO J 53472; COLO J 53636.

Detail of the rim of the chamber pot illustrated in figure 35. (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The initials are possibly those of William Berkeley, governor of Virginia during the period in which the pot was manufactured.

Candlestick, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Sgraffito slipware. H. 6 5/16". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park) COLO J 12342. Because of its rarity, this is one of the most important ceramic objects in the archaeological collections of the National Park Service at Jamestown.

Fragments of incomplete candlestick, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Sgraffito slipware. (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) COLO J 53453; COLO J 53454; COLO J 53460. This candlestick is decorated on all exterior surfaces with floral devices

Porringers, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Slipware. Left: H. 3"; right: H. 3 1/4". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Left: COLO J 7331; right: COLO J 7333. These examples represent the two porringer forms found.

Dishes, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Slipware. D. 9", 10 1/2". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Smaller: COLO J 7337; larger: COLO J 7300. These wavy edge dishes occur in graduated sizes.

Dish, North Devon, ca. 1670–1680. Slipware. D. 9 1/2". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) COLO J 7340.

In 1935, when historical archaeology was in its infancy, National Park Service archaeologists working at Jamestown, Virginia, made a remarkable discovery. They found an astonishingly large assortment of decorated slipware vessels in a meandering drainage ditch on the periphery of a seventeenth-century site known as the May-Hartwell property. The feature that produced the artifacts was a formal brick drain built over an older U-sectioned ditch from which over 600 fragments were cataloged. Although the archaeologists could not identify all of the wares at the time of their recovery, the collection was recognized as significant by the sheer quantity of restorable slipware vessels.

The restorable ceramics include not only sgraffito-decorated wares but also many other gravel-tempered coarse earthenware utilitarian vessels as well as seventeenth-century English delftware objects. Soon after excavation, the slipwares were mended and restored by technicians at Jamestown (fig. 1). At least forty-seven slipware vessels and many more large fragments were cataloged. Almost seven decades since its recovery, the assemblage remains a prominent component of the archaeological collections at the National Park Service’s Colonial National Historical Park (fig. 2).[1]

Four years after they were unearthed, the slipwares were finally identified as having been made around 1670 in the coastal region of North Devon in southwestern England.[2] Representing a wide range of shapes, most of them are scratched, or sgraffito-decorated, with bold motifs that cut through a white slip into leather-hard pinkish-red clay.[3] They are glazed with transparent lead, which appears bright amber over the white slip. The glaze over the red body, particularly in the lines of the carved designs, appears brown. Because of the sizable number of vessels represented, their completeness, and their wide-ranging forms and decorative motifs, this assemblage has remained the most significant collection of seventeenth-century North Devon slipware in Britain or America. These wares provide a unique insight into the bold, stylistic trends of the period, and their graphic qualities still appeal to a wide audience today (fig. 3).

North Devon Ceramics

In 1960, C. Malcolm Watkins published the pioneering study of North Devon wares, focusing on the May-Hartwell collection from Jamestown. His research laid the groundwork for documenting the considerable seventeenth-century trade and familial connections between North Devon and America. In 1983, Alison Grant published a complete history of the seventeenth-century North Devon pottery industry, expanding on the Devon and American connections. Both researchers used the Devon Port Books to provide evidence of an active ceramic trade with America beginning as early as 1635. However, not only does the archaeological record of the New World provide evidence of the actual product, it also demonstrates that these wares arrived before 1635.[4]

From medieval times, pottery was being produced in North Devon, but in the seventeenth century, it flourished as an industry. Its success was closely related to the prosperous shipping trade that originated in the sixteenth century from the port towns of Barnstaple and Bideford (fig. 4). Ceramics could be transported far more economically by sea than by land, thus they were promoted and shipped in great quantities to ports in England, Wales, Ireland, and America during the seventeenth century.[5]

Contributing to this booming production in the seventeenth century were the readily available local resources used in pottery manufacture. These included clays from Fremington; water worn gravel for temper from the Rivers Torridge and Taw; and white ball (or tobacco-pipe) clay for slip from Peters Marland. Most lead ore for glaze was brought in, and large imports of coal into North Devon suggest it was the primary fuel for firing the kilns.[6]

Pottery production was Bideford’s most important seventeenth-century industry, adding considerably to the wealth of England during that century. The nearby market town of Barnstaple also was a major production center during the era. To a lesser extent, earthenware was made in and near other towns in the region, such as Great Torrington.[7]

Although sgraffito slipware was the most decorative pottery type manufactured in seventeenth-century North Devon, other earthenwares were produced in a vast range of shapes to fulfill consumer needs. For example, baluster-shaped jars, in a fabric known as North Devon Plain, were made in enormous quantities from the late sixteenth century and into the seventeenth century as containers for foodstuffs such as fish and butter. Thus, filled with provisions, they were carried in 1585 with the first British colonists to the New World, only to be discarded at the short-lived North Carolina coastal settlement of Fort Raleigh. These shapely jars represent the principal North Devon earthenware form found on Anglo-American sites from the first quarter of the seventeenth century.[8]

Another ware that North Devon potters began making in the early seventeenth century is the distinctive gravel-tempered coarse earthenware, by far the easiest of all coarse earthenwares to identify. Water worn gravel from fresh waters was used to temper the utilitarian coarse earthenware products, thereby strengthening the fabric, and enabling the ware to be used on the hearth and in bake ovens. Although this ware type has been found as early as circa 1620–1622 on Anglo-American sites, it is most commonly recovered from sites dating after circa 1640. This type of ware was manufactured well into the eighteenth century, and is found in archaeological contexts in America until the Revolutionary War. Forms of gravel-tempered vessels exported to America include pipkins, cooking pots and lids, three-legged cauldrons, large dome topped ovens, storage jars, and most frequently, milk pans.[9]

The most ornamental of the North Devon ceramic wares is, of course, slipware. Three types of slip decoration can be identified: plain slip coating; trailed slip; and sgraffito designs that are cut through a plain slip. Although this later category encompasses many highly decorated forms, surprisingly few seventeenth-century examples have survived as antiques. This suggests that their prominence in the archaeological record is a function of their basic utilitarian nature.

The wares of Northern Europe, where the sgraffito technique had been used since the sixteenth century, clearly influenced North Devon slipware potters. Some evidence also suggests that immigrant potters may have directly influenced the products of North Devon. Like Continental potters, and unlike others in England, North Devon potters fired their slipware twice: the first, a biscuit (unglazed) firing after slipping and sgraffito decorating, and the second, a glost (glaze) firing after the application of the liquid lead glaze. Furthermore, the vessel forms, decorations, and the technique of scratching a design through a white slip are evocative of pottery from Germany and the Low Countries. Also, they bear an uncanny resemblance to the double-slipped wares made from the early sixteenth century onward in Beauvais, Northern France, strongly suggesting these wares influenced seventeenth-century North Devon potters (fig. 5).[10]

Slipware manufacture by North Devon potters reached its peak in the third quarter of the seventeenth century, and began to wane at the end of the century. By that time, potters faced competition from the delftware industry and the well-organized Staffordshire potters who were producing more sophisticated wares in larger quantities, in a wider range of shapes and decoration, and more economically because of their location and resources. Thereafter, and until the late nineteenth century, North Devon slipware potters specialized in the production of more ornately sgraffito-decorated forms, such as the well-known ceremonial “harvest jugs” (fig. 6).[11]

At least one North Devon amber-colored sgraffito slipware dish had made its way to America by 1622. It was retrieved from a site of that date at Martin’s Hundred near Jamestown, Virginia. A few more dish fragments have been recovered from other nearby sites dating to the second quarter of the seventeenth century. The early examples are deeply sgraffito-decorated by a single, wide implement. The decoration appears on the interior, with a running S-scroll device on the rim, and all but the earliest examples display a bird and leaf motif in the center (fig. 7).[12]

In the second half of the seventeenth century, North Devon slipware is represented on most Chesapeake archaeological sites of all socio-economic levels by at least one or two vessels. Stylistically, their designs are more sophisticated and well executed than the earlier examples, and a wider range of forms is represented. Mirroring the industry-wide decline in production, North Devon slipware disappears from the Anglo-American archaeological record around the end of the seventeenth century.

The May-Hartwell Collection

Although North Devon slipware is regularly encountered on sites in America in the second half of the seventeenth century, it is rarely found intact or in large quantities. The extraordinary exception to this is the May-Hartwell collection. The property within the spreading settlement of Jamestown was patented by attorney William May in 1661, and was owned by four different title-holders in the remainder of that century, ending with Henry Hartwell who died in 1699. Colonel William White, a highly successful merchant and planter, may have been living there as early as 1673, and he owned the property from 1677 until his death sometime before August 1682. Since White was the only merchant among the four owners, it is very likely that the North Devon ceramics were part of a shipment intended for sale in the marketplace, arriving circa 1673–1682 during his tenure on the property.[13]

The shipment of ceramics appears to have been broken in transit. When it arrived, the dishes, jugs, and mugs were used to line a ditch to promote drainage of White’s low-lying property.[14] Although victim to an unfortunate shipping mishap, the assemblage serves as an unique time capsule demonstrating the range of North Devon slipware forms available to Virginia consumers in the 1670s. In this respect, it differs from the large ceramic assemblages that are commonly recovered from kiln excavations, because those illustrate discards and forms made over a longer period. In contrast, the May-Hartwell group shows the kinds of ceramics sent to the colony and the sorts of choices available to colonial consumers.

Included in the wide range of slipware forms are: porringers; large dishes; plates; shallow piecrust-edge plates (pie plates); wavy edge dishes (possibly meat pie dishes); handled bowls; a milkpan; mugs; jugs; chamber pots; and candlesticks. The fabric of most of the vessels is fine, chalky earthenware, appearing in tones of pinkish- to brownish-orange to gray because of both oxidizing and reducing firings. The broken edges are laminated and some display gravel inclusions.

All of the May-Hartwell slipware vessels were wheel-thrown. The flatware was covered on the interior with a white slip, as was the exterior of hollow ware. Some were simply covered with a plain white slip, but most were sgraffito-decorated. None of the vessels were slip-trailed.

The sgraffito decorations were quickly and skillfully scratched through the slip with single- and/or multi-pointed tools while it and the underlying fabric were still damp. The use of stippling augmented the primary scratched lines. The potters were clearly influenced by popular designs on furniture, metalwork, embroidery, and other ceramics such as imported slipware, and English and Continental tin-glazed earthenware (fig. 8). Emulating the prevailing tastes of the day, geometric principles prescribed the position of the flowers, leaves, zigzags, chevrons, curlicues, s-scrolls, and other motifs on the vessels.[15]

No two objects are decorated identically, but the same stylized floral and/or geometric devices are often repeated. Similarities in motifs, the standardization of forms, and the visual quality of the pieces suggest that they were products of the same kiln, and that the same person or just a few individuals decorated them. The multi-pointed tool used to create the parallel striped lines and stippling varied from vessel to vessel, as their numbers ranged from three to five points. On each individual vessel, however, the same multi-pointed tool generally was used to draw the parallel lines and to punch the stippled lines (fig. 9).

Sgraffito-Decorated Flatwares

Well represented in the May-Hartwell assemblage are sgraffito-decorated flatwares, including large dishes, small plates, and one shallow plate with a piecrust rim. Most numerous of all of the reconstructed vessels in the collection are twenty large plate-form dishes that range in diameter from eleven and one-half to fifteen inches (fig. 10). They are slipped, incised, and glazed on the interior only. Each has an upturned marly (flanged section between the rim and bouge, the cavetto, or curved section) with a thickened rim, rounded and tooled on the interior edge (fig. 11). A prominent, tooled ridge appears on the interior at the marly/bouge junction. The bouge curves inward gently to a flat base. In contrast to the detailed decoration of the interior surface, the unglazed exteriors exhibit hasty knife trimming above the bases, numerous kiln scars, elongated drips of slip and glaze, wipe marks, and finger impressions in the fabric, indicating the importance of speed in production (fig. 12).

Of all the sgraffito-decorated slipware, the most elaborately decorated are nine large dishes with floral motifs (fig. 13). The marlys of six reconstructed examples are incised with combinations of spiral asterisks, daisies, hanging flowers, tulips, and floral swags (fig. 14). One marly, however, bears a chain device; another, a swag and tassel motif (fig. 15).

Seven dishes are adorned with large symmetrical floral and foliate designs that cover the interior base and bouge, and include flowers such as daisies, carnations (or thistles), and tulips. Two, though, are ornamented with smaller central floral medallions on the base that are encircled on the bouge, a swag on one, and floral sprays on the other (fig. 16). One unusual dish represented only by fragments is decorated with bunches of grapes on the marly/ bouge/base (fig. 17).[16]

Eleven large dishes are incised on the interior with geometric patterns in three zones. With one exception, they have curlicues on the marly; the exception has chevrons (fig. 18). Drawn with multi-pointed tools, the bouge decoration varies from straight-sided squares to U-shaped swags, and frames the central motif.[17] One dish is centrally adorned with alternating rows of wavy lines and dots. The circular-shaped central medallions of ten others are filled with compass drawn geometric decorations. Three are highly ornamented variations on the “Chinese butterfly” motif with two large lozenge-shaped, wing-like devices (fig. 19).[18] The remaining dishes are decorated with four- to six-pointed stars or flowers adorned with curlicues, stippled lines, dots, and wavy lines (fig. 20).

Areas on the interior surfaces of two dishes were damaged prior to the glost firing. Apparently, a vessel, such as a jug or porringer was placed in one dish while still damp. When the object was removed, so too was a circular portion of the decoration (fig. 21). It and the other damaged dish were glazed anyway, and their presence confirms that these “seconds” were sent to America.

Eight small plates, and fragments of many more, were recovered from the ditch. Only about seven to seven and three-fourths inches in diameter, their shape is comparable to that of the large dishes. Similar to the dishes, the plates are slipped, decorated, and glazed only on the interior, and the decoration occurs in zones. The marlys of the intact examples have curlicues, but fragments of several others are incised with swags (see fig. 3). Covering the interior base and bouge, the central motifs include stippled multi-petaled flowers (fig. 22), a tulip (fig. 23), and a cruciform device made up of overlapping circles (fig. 24). Like their larger cousins, the exteriors display evidence of knife trimming, fingerprints, and glaze drips.

One shallow sgraffito-decorated plate (fig. 25) is slipped and geometrically inscribed on the interior with crossed stems terminating with elaborate carnations (or thistles). The rim has a piecrust edge, and it is glazed on the interior only (fig. 26). Like the dishes and plates, the unglazed exterior was knife trimmed above the base and displays a wealth of fingerprints.

Sgraffito-Decorated Hollow Wares

Sgraffito–decorated hollow wares are represented by mugs, jugs, and deep handled-bowls. All about three and one-half inches in height, four mugs in three different shapes were restored. Each has a single, vertical handle. The mugs are slipped and incised on the exteriors with stylized floral or abstract designs. Lead glazes cover the interiors and exteriors. Two gorge-shaped (globular with tall vertical rims) mugs are adorned with floral motifs (fig. 27). A third mug, bulbous in form, is incised with vertical rows of combed lines alternating with vertical rows of dots and dashes (fig. 28). The fourth example has concave sides and is ornamented with quatrefoil flowers, curlicues, and stippled lines (fig. 29).

Ranging from six and three-fourths to eight and three-fourths inches in height, six sgraffito-decorated jugs are included in the assemblage of mended vessels. Each jug has a single vertical handle made of gravel-tempered coarse earthenware. Their vertical necks are horizontally ribbed and grooved, and their bodies are bulbous. They are slipped on the exterior, and glazed on the interior and upper exterior. The bodies are incised on the upper half with stylized motifs. Decorations include stippled multi-petaled flowers and vertical lines (fig. 30), stippled quatrefoil flowers and tulips (fig. 31), carnations (or thistles) with leaves flanking a central quatrefoil flower (fig. 32), and a vertical pattern of stippled horizontal lines, wavy lines, and combed vertical lines (fig. 33).

Two deep bowls recovered from the ditch are the only hollow wares decorated on the interior (fig. 34). Both are the same size and have a single horizontal loop handle on the rim. One is incised on the central base with a quatrefoil flower, and on the interior walls with spirals and elaborate hanging flowers. The other is decorated with an abstract design consisting of horizontal wavy lines and vertical stippled lines separated by vertical combed stripes.

Sgraffito-Decorated Comfort Wares

Not all of the decorated forms in the assemblage were for food preparation or serving; two were made to meet daily needs: chamber pots and candlesticks. One almost complete bag-shaped chamber pot (fig. 35) was recovered, along with fragments of two others (fig. 36). They are incised on the exterior with motifs including stippled multi-petaled flowers, rows of dotted circles, and chevrons separating horizontal rows of wavy lines alternating with rows of dashes. Slip and lead glazes cover the interiors and exteriors.

The most intact of the three chamber pots has a rim diameter of six and three-fourths inches and is inscribed “WB 16__” (fig. 37). Could this pot have been made for William Berkeley, the governor of Virginia until his death in 1677, thereby providing a terminus ante quem for the collection? White and Berkeley were linked, as shown in a 1674 court record documenting that one of Berkeley’s indentured servants was obligated to serve White for a year and a half for boat stealing.[19] Did White specifically order the inscription to show his appreciation, or later to demonstrate his loyalty to Berkeley during a period of civil unrest leading up to Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676? Although these questions can probably never be answered with any certainty, they demonstrate the potential for linking forgotten artifacts with historic people or events.

One of the most important of all the North Devon slipware forms recovered is a handled candlestick with a flared base and mid-section drip tray (fig. 38). Fragments of a least one other example were also found (fig. 39). These mid-drip candlesticks have parallels in delft and metal forms. Their top half exteriors are slipped and decorated with stylized stippled floral motifs.

Undecorated Slipware

Slipped but undecorated vessels include a shallow plate with a piecrust rim, large dishes, porringers, dishes with wavy edges, and a milkpan. Paralleling the decorated example, the shallow plate exhibits a pinched piecrust rim and is nine and three-fourths inches in diameter. It is glazed on the interior only, and displays knife trimming on the exterior above the base.

Three large dishes, eleven and one-half to twelve inches in diameter, are slipped and glazed on the interior only. They are similar in form and size to the sgraffito-decorated examples. And like the incised dishes, all exhibit knife trimming on the exterior above the base.

Ranging in height from two and one-half to three and one-fourth inches, six porringers appear in two forms, carinated and bulbous (fig. 40). Bearing a single horizontal loop handle applied at the waist, two carinated examples are slipped and glazed on the interior and just over the rim. Resembling delftware forms, the four bulbous porringers each have one horizontal loop handle just below the rim. They are slipped and glazed on the interior, and are unglazed on the exterior. Rough on the exterior bases, the porringers appear to be lightly gravel tempered.

Four wavy-edged baking dishes are represented in the assemblage. In graduated sizes, their rim diameters range from eight to ten and one-half inches (fig. 41, 42). Flat based, their tall vertical sides were pinched when the clay was damp to form corners and seven, eight, nine, or eleven sides. They are slipped and glazed on the interior and just over the rim exterior, and are horizontally grooved just below the rim exterior and/or interior.

Sherds of a unique slipware milkpan also survive. The fabric and form of this fragmentary object are typical of North Devon gravel-tempered coarse earthenware, but a white slip under a lead glaze covers the interior below the rim. This example, along with the handles on the six incised jugs and the porringers, show that gravel-tempered earthenwares and slipwares were produced at the same kiln.

Conclusion

Somewhere between the coastal North Devon region of England and Jamestown, Virginia, a large ceramic shipment was broken. The fragmented vessels were discarded in a ditch dug to provide drainage for flat, low-lying property at Jamestown, which in the twentieth century was named May-Hartwell for its first and last seventeenth-century owners. The sheer number and range of forms indicate that they were intended for more than one household. Since Colonel William White was the only merchant owner of the property, it is extremely likely that the parcel was shipped to him during his occupancy, which may date as early as 1673.

This fortuitous accident, while disastrous for the owner at the time, has provided a legacy of the most complete example of North Devon sgraffito-decorated slipwares in the world. With forty-seven restored vessels represented, and fragments of many, many more, the May-Hartwell assemblage also gives us a unique view of everyday life in Virginia during the 1670s. As we examine these ceramics intended to fulfill the colonists’ daily needs and activities, doorways to their kitchens, bedchambers, dairies, taverns, and even their minds, are opened. Skillfully scratched in clay, the decoration gives us a firsthand look at the stylistic trends and tastes of the time. We may also contemplate the potters who threw and decorated these remarkable vessels over three hundred years ago. Could they possibly have imagined the fate of their work and the enduring effect of their creations?

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Curator David Riggs and Museum Technician William Calhoon of the National Park Service’s Colonial National Historical Park for always making the collection and other research materials available to me. Also, for generously sharing their thoughts on the collection, I extend my appreciation to colleagues and fellow ceramics enthusiasts Beverly Straube, Taft Kiser, Robert Hunter, Michelle Erickson, Richard Coleman-Smith, and last, but in no way least, Alain Outlaw.

John L. Cotter, Archeological Excavations at Jamestown, Virginia, 2nd ed. (Richmond: Archeological Society of Virginia, 1995), pp. 68–74. H. Summerfield Day, “Preliminary Archeological Report of Excavations at Jamestown, Virginia,” 1935, typescript, Colonial National Historical Park. J. C. Harrington, “Summary of Documentary Data on the William May-Henry Hartwell Property Preparatory to its Excavation,” 1938, typescript, Colonial National Historical Park. J. C. Harrington, “Archeological Report: May-Hartwell Site, Jamestown, Excavations at the May-Hartwell Site in 1935, 1938, and 1939 and Ditch Explorations east of the May Hartwell Site in 1935 and 1938,” 1940, typescript, Colonial National Historical Park.

Although the potter or potters and place of manufacture of these vessels have yet to be identified, examples uncovered in Barnstaple are similarly sgraffito-decorated. Many marly motif parallels have been recovered from kiln excavations in North Devon. Linda Blanchard, Archaeology in North Devon 1987–8 (Barnstaple, Eng.: North Devon District Council, 1989), pp. 16–19. Alison Grant, North Devon Pottery: The Seventeenth Century (Exeter, Eng.: A. Wheaton & Co. Ltd, 1983), plates 8–15, 17. C. Malcolm Watkins, “North Devon Pottery and Its Export to America in the Seventeenth Century,” United States National Museum Bulletin 225 (Washington, D.C.: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1960), p. 20.

Michelle Erickson and Robert Hunter, “Dots, Dashes, and Squiggles: Early English Slipware Technology,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 98–101.

Watkins, “ North Devon Pottery and its Export to America in the Seventeenth Century.” Grant, North Devon Pottery: The Seventeenth Century.

Port records indicate that only fifteen percent or less of North Devon’s overseas exports was to America. Grant, North Devon Pottery: The Seventeenth Century, p. 114.

Ibid., pp. 35–46.

Ibid., pp. 1–33.

Ivor Noël Hume, “First Look at a Lost Virginia Settlement,” National Geographic Magazine 155, no. 6 (June 1979): 735–37. Ivor and Audrey Noël Hume, The Archaeology of Martin’s Hundred Part I: Interpretive Studies (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), pp. 166–68. Alain Charles Outlaw, Governor’s Land: Archaeology of Early Seventeenth-Century Virginia Settlements (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1990), pp. 105–8.

Ivor and Audrey Noël Hume, The Archaeology of Martin’s Hundred Part I: Interpretive Studies, pp. 166–68.

Sgraffito decoration of ceramics passed from China, through the Middle East, and then to Italy in the Middle Ages. From the sixteenth century on, the technique spread to Switzerland, Germany, France, and the Low Countries. Double slipping, or the application of a white slip over a red slip before sgraffito decorating, was used in Northern Europe. European sgraffito decorated wares are well represented on post-medieval archaeological sites in southwestern England, therefore serving as prototypes. In addition, techniques, forms, and designs may have come into southwestern England by way of refugee Huguenot and Netherlands Protestant artisans, who may have included potters. Grant, North Devon Pottery: The Seventeenth Century, p. 2; Leslie B. Grigsby, English Slip-Decorated Earthenware at Williamsburg (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1993), p. 19. John G. Hurst, David S. Neal, and H. J. E. Van Beuningen, “Pottery Produced and Traded in North-West Europe, 1350–1650,” Rotterdam Papers 6 (Rotterdam: Museum Boymans-van Beunigen, 1986), pp. 30–33. Hans van Gangelen, Peter Kersloot, Sjek Venhuis, Hoorn des Ouervloeds: De Bloeiperiode van Het Noord-Hollands Slibaardewerk, Ca. 1580–Ca. 1650 (Stiching Noord-Hollands Slibaardewerk Oosthuizen: Stichting Uitgeverij Noord-Holland Wormerveer, 1997). Ivor Noël Hume, If These Pots Could Talk: Collecting 2,000 Years of British Household Pottery (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 35–36.

Grant, North Devon Pottery: The Seventeenth Century, pp. 131–34.

Ivor and Audrey Noël Hume, The Archaeology of Martin’s Hundred Part II: Artifact Catalog (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), pp. 237–39, 300–303. Seth Mallios, Archaeological Excavations at 44JC568, The Reverend Richard Buck Site (Richmond: Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, 1999), p. 32.

Analysis of the ditch artifacts has always been difficult because of the lack of excavation field notes, drawings, and photographs. Because of the presence of glass wine bottle seals bearing the initials of Henry Hartwell, who patented the land in 1689, the deposit has always been related to him, thus post-dating 1689. Various explanations include rebuilding activities during Hartwell’s occupation, discarding out of date ceramics, a household or shipping accident, and destruction at the end of Hartwell’s residency in 1695. It is this author’s opinion, however, that the restorable vessels, including North Devon gravel-tempered earthenware, North Devon sgraffito slipware, and English delftware, were broken in shipment to merchant Colonel William White, and the large ceramic fragments were used as drainage fill for the earlier U-sectioned ditch. Later, the very fragmentary domestic artifacts, including the “HH” bottle seals, bone combs, delft tiles, roofing tiles, turned lead, window glass, and flooring tiles, were discarded. This later material is very different in character from the large ceramic sherds, and it does suggest house-remodeling activities. Interestingly, White’s widow married Hartwell. Harrington, “Summary of Documentary Data on the William May-Henry Hartwell Property Preparatory to Its Excavation.” Cotter, Archeological Excavations at Jamestown, Virginia, pp. 68–74.

Archaeological parallels demonstrating the use of ceramic sherds for fill are common. For example, pottery waste was used as fill for drainage in the “soakaway” trenches and pits at John Dwight’s late seventeenth-century Fulham pottery near the River Thames. Chris Green, John Dwight’s Fulham Pottery: Excavations 1971–79 (London: English Heritage, 1999), p. xii. In the early eighteenth century, stoneware wasters from the Southwark Bankside Kiln in London were used to line drainage channels and to strengthen the River Thames’ shoreline. Saggers and wasters from the William Rogers pottery factory were used to surface roads in Yorktown, Virginia, in the second quarter of the eighteenth century. Ivor Noël Hume, Here Lies Virginia (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1963), pp. 221–22. Remarkably, whole vessels were used to fill a ravine at the Baynham stoneware pottery factory near Trenton, South Carolina, in the 1880s. Mark M. Newell, “A Spectacular Find at the Joseph Gregory Baynham Pottery Site,” in Ceramics in America (2001), ed. Robert Hunter, pp. 229–32.

Grant, North Devon Slipware: The Seventeenth Century, pp. 58–59.

Grapes are common motifs on Germanic and Low Countries slipwares. Anton Bruijn, Spiegelbeelden: Werra-Keramiek uit Einkhuizen 1605 (Zwolle: Stiching Tromotie Archeologie, 1992), pp. 259–62. van Gangelen, et al.,Hoorn des Ouervloeds, figs. 85, 105, 124, 128, 129. Hurst, et al., “Pottery Produced and Traded in North-West Europe,” pp. 244–45.

The use of scalloped medallions to frame the central motifs was common on German and Low Countries slipware dishes, and emulated similar decorative devices on Chinese porcelain dishes of the period. Bruijn,Spiegelbeelden, pp. 64–84. Hurst, et al., “Pottery Produced and Traded in North-West Europe,” pp. 243–44. C. L. Van der Pijl-Ketel, ed., The Ceramic Load of the “Witte Leeuw” 1613 (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 1982), pp. 53–80.

Grant, North Devon Slipware: The Seventeenth Century, p. 59.

Martha W. McCartney, James City County: Keystone of the Commonwealth (James City County, Va.: Donning Company, 1997), pp. 111–13.