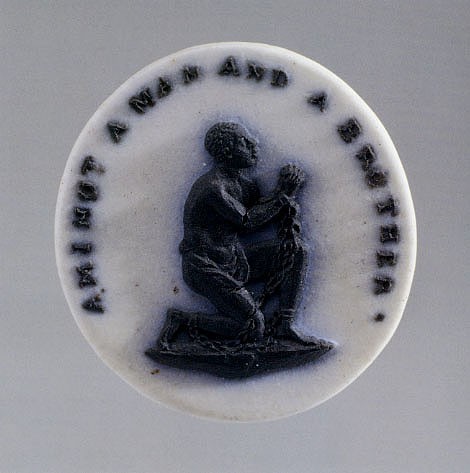

Medallion, Josiah Wedgwood, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1787. Jasperware. D. 1 1/8". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Design of chained and kneeling slave in profile taken from the seal of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade

Medallion, Josiah Wedgwood, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1787. Jasperware and silver. D. 1 7/8". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

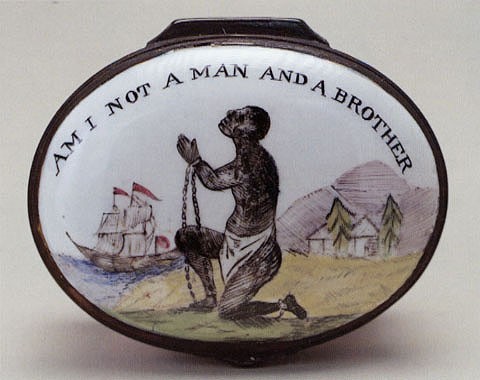

Patch box, England, ca. 1800. Painted enamel on metal. L. 1 3/4". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

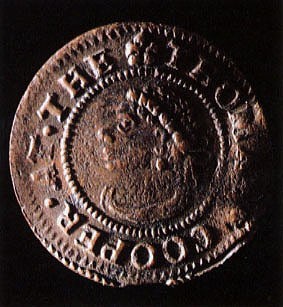

Halfpenny token, 1668. Copper. D. 7/8". (Collection of the author; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Head of black youth representing the Black Boy Pub.

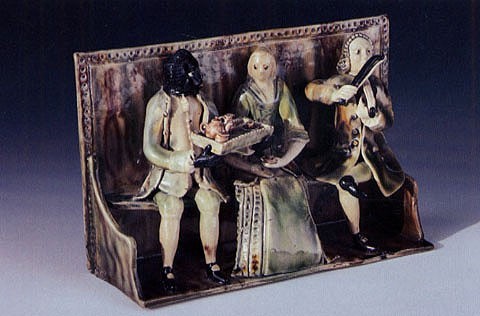

Figural group, Staffordshire England, ca. 1760. Creamware. H. 5 3/8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

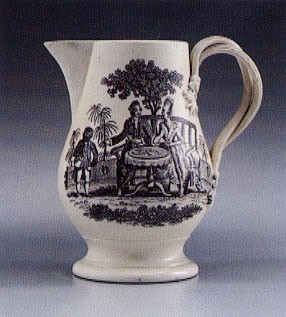

Cream jug, Staffordshire or Yorkshire, England, 1780–1790. Creamware. H. 4 1/2". (Collection of the author; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This jug, part of a larger tea service, has twisted strap handles with molded sprigs terminals and a black transfer print of The Tea Party.

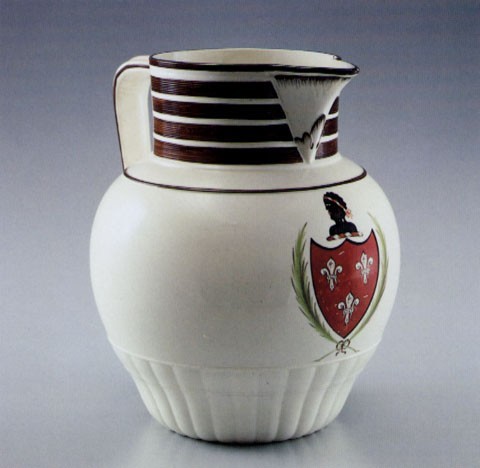

Jug, England, ca. 1800. Pearlware. H. 9 1/2". (Collection of the author; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Armorial crest featuring blackamoor bust in profile.

Detail of the crest illustrated in figure 7.

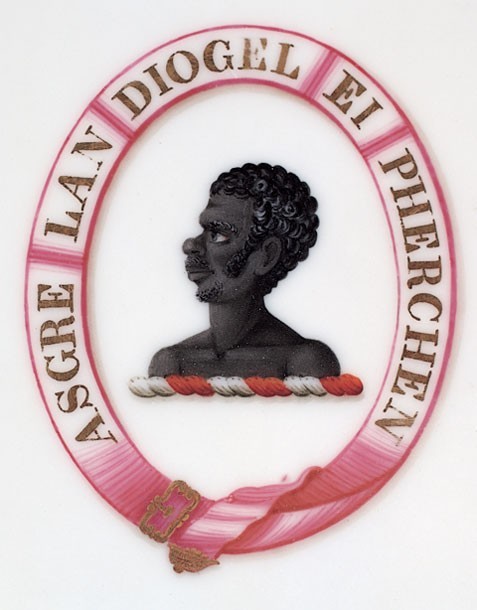

Soup plate, France, ca. 1810. Porcelain. D. 9 3/4". (Collection of the author; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Blackamoor head and legend “Asgre Lan Diogel ei Pherchen.”

Detail of the soup plate illustrated in fig. 9. The Latin legend translates as “A pure conscience is a safeguard to its possessor.”

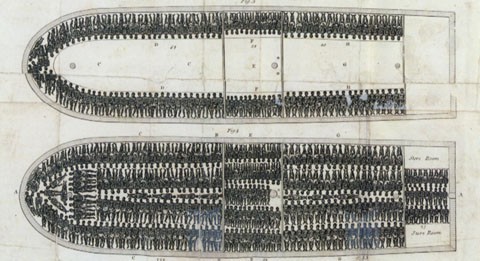

Detail of an engraving, from Thomas Clarkson’s History of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade, London, 1807. Influential figures such as Thomas Clarkson were given the responsibility of collecting information to support the abolition of the slave trade. This included interviewing 20,000 sailors and obtaining equipment used on the slave ships such as iron handcuffs, leg-shackles, thumb screws, instruments for forcing open slaves’ jaws, and branding irons. In 1787 he published his pamphlet, A Summary View of the Slave Trade and of the Probable Consequences of Its Abolition. After the abolishment of the British slave trade in 1807, Clarkson published his book History of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade.

Child’s mug, England, ca. 1840. Whiteware. H. 2 1/2". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This enamel-colored black transfer print depicts the capture of native Africans by European slavers, along with the opening verse from William Cowper’s The Negro’s Complaint: “Forcd from home and all its pleasures/Afric’s coast we left forlorn/To increase a stranger’s treasures/O’er the raging billows borne.”

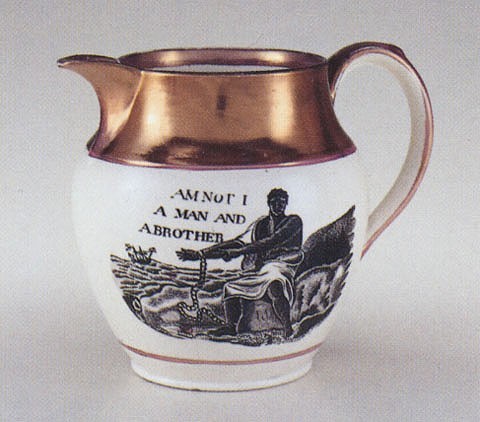

Jug, Staffordshire or Sunderland, ca. 1820. Pearlware. H. 4 1/2". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo Gavin Ashworth.) This jug with copper and pink luster trim shows a transfer-printed variation of the Wedgwood plaque design. This one features a frontal view of a chained and seated slave, and verses from William Cowper’s The Negro’s Complaint on the other side. Note the reversal, most likely unintentional, of “I” and “Not” in the printed motto.

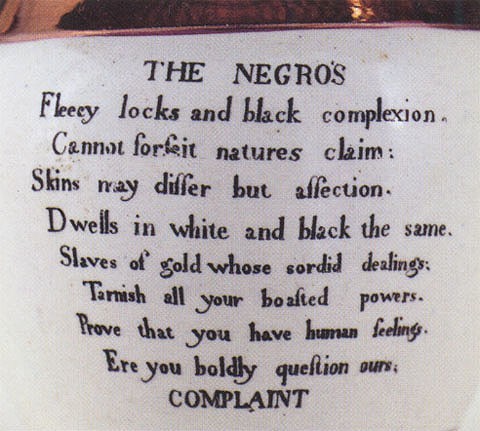

Detail of the reverse of the jug illustrated in fig. 13. This stanza from The Negro’s Complaint reads (italics mine): “Slaves of gold, whose sordid dealings/ Tarnish all your boasted powers,/Prove thatyou have human feelings/Ere you proudly question ours!”

Figural group, France or England, ca. 1820. Porcelain. H. 6 1/4". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) A late eighteenth-century antislavery pamphlet by William Fox included a section on punishment in which a Royal Navy admiral attested that the flogging of slaves was much more severe than that administered to sailors aboard English men-of-war. More explicitly, an English general asserted “there is no comparison between regimental flogging, which only cuts the skin, and the plantation, which cuts out the flesh.”

Reverse view of the figural group illustrated in fig. 15.

Mug, England, ca. 1850. Porcelain H. 3". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) In elaborate gold script: “Health to the Sick/ Honour to the Brave/Success attend true Love/ And Freedom to the Slave."

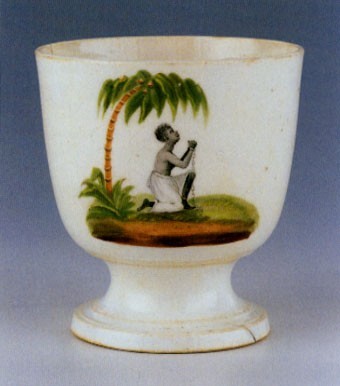

Sugar bowl, England, 1820–1830. Bone china. H. 4 5/8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) The decoration of the kneeling slave in the tropical environment is enameled over the glaze suggesting that it may have been produced for a special anti-slavery fair or occasion.

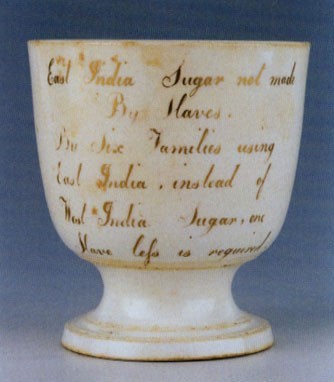

Reverse of the sugar bowl illustrated in fig. 18. Legend reads: “East India Sugar not made/By Slaves/By Six families using/East India, instead of/West India Sugar, one/Slave less is required.” The wording represents a somewhat sanitized version of Fox’s formulation that “A family that uses 5 lb. of sugar per week...will, by abstaining from the consumption 21 months, prevent the slavery or murder of one fellow creature” and tactfully omits the pamphleteer’s more gruesome analogy “that in every pound of sugar used...we may be considered as consuming two ounces of human flesh.”

Sugar bowl and cover, England, 1820–1830. Earthenware. H. 5". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Transfer-printed image of the kneeling slave. This bowl would have been part of a larger tea service. A number of different ceramic forms were decorated with this transfer print, including teawares and dinnerwares.

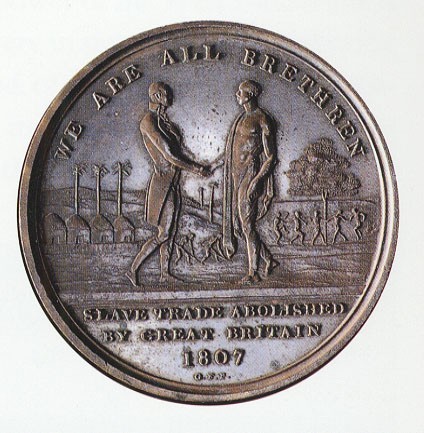

Token, 1807, copper. D. 1 3/8". (Collection of the author; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Reverse engraving on glass, London, 1807. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) Published to commemorate the abolishment of the British slave trade, this depiction, rich in iconographic imagery, shows the figure of Africa casting a disapproving eye toward America who holds the images of Washington and Franklin.

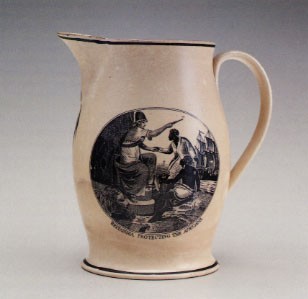

Jug, Liverpool, 1805–1810. Creamware. H. 8 1/4". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The transfer on this jug is captioned: “Britannia Protecting the Africans.”

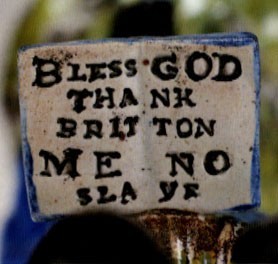

Figure, Staffordshire, 1790–1810. Pearlware. H. 7". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This early kneeling slave, hand enameled in high temperature underglaze colors, is holding a book inscribed “bless god thank briton me no slave.” While not specifically identified as such, the early date of this ceramic figure must coincide with the British abolishment of the slave trade begun in 1792 and formally decreed in 1807.

Figural group, possibly Staffordshire, early nineteenth century. Porcelain. H. 6 5/8". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) In this figural group, a slave exults in freedom as broken chains and whip lie on the ground. An open Bible rests at Britannia’s feet.

Detail of the inscription on the book held by the kneeling figure illustrated in fig. 24.

Plate, England, ca. 1840. Whiteware. D. 8". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Molded daisy pattern rim with black transfer print advocating “Brotherhood and Free Trade with all the World.”

Plate, France or England, ca. 1830. Porcelain. D. 9". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Inscribed “Unfettered Intercourse between all Nations—The Best Security for Abundance and Peace.”

Soup plate, Staffordshire, ca. 1840. Whiteware. D. 10 1/2". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jugs, Staffordshire, ca. 1840. Whiteware. H. of tallest. 6 1/4". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jug, Staffordshire, ca. 1840. Whiteware. H. 4 1/4". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Child’s plate, England, ca. 1820. Pearlware. D. 5". (Collection of the author; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This blue transfer print extolling the virtues of “my bible” is derived from a color sheet published by William Darton, Jr. in 1812.

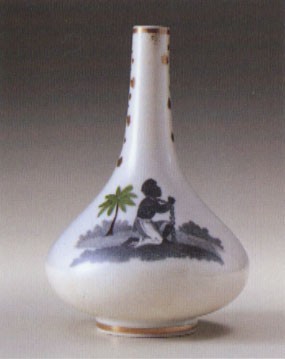

Vase, France, ca. 1820. Porcelain. H. 4 3/4". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

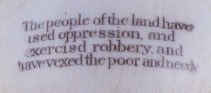

Detail of the inscription on the vase illustrated in fig. 33.

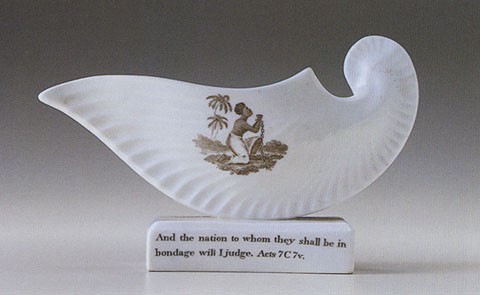

Sauceboat, France, ca. 1820. Porcelain. L. 5 1/2". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Black transfer print of a kneeling female slave in chains.

Dish, France, ca. 1820. Porcelain. L. 10". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Cup and saucer, England, ca. 1830. Drabware. D. 5 1/8". (Collection of the author; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Black transfer print of kneeling female slave in chains (cup).

Detail of the saucer illustrated in fig. 37.

Detail of the saucer illustrated in fig. 37.

Plate, England, ca. 1830. Drabware. D. 6 1/2". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This small plate, part of a larger tea service, bears the caption from the engraving which faces the title page in Mary Dudley’s pamphlet, Scripture Evidence of the Sinfulness of Injustice and Oppression: “This Book tell Man not to be cruel; Oh that Massa would read this Book.”

Token, United States, 1838. Copper. D. 1 1/8". (Collection of the author; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Kneeling and chained female slave with legend: “am i not a woman & a sister.”

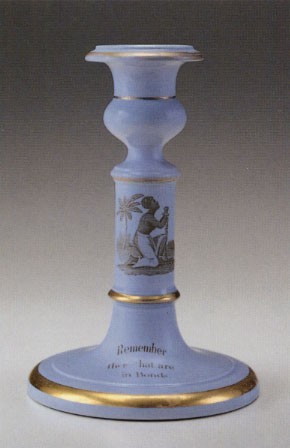

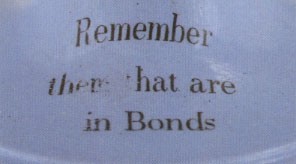

Candlestick, England, ca. 1830. Earthenware. H. 6 1/4". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This unusual form has the transfer print of a kneeling female slave and the Bible verse: “Remember them that are in Bonds.”

Detail of the gilt inscription on the base of the candlestick illustrated in fig. 42.

Set of figures from Uncle Tom’s Cabin, England, ca. 1855. Unglazed porcelain. H. of tallest: 3 1/4". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Plate, probably Staffordshire, ca. 1855. Whiteware. D. 6 1/6". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The printed scene shows “The Death of Uncle Tom.”

Plate, J. Vicellard, Bordeaux, France, ca. 1855. D. 8". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) A French version of the death of Uncle Tom.

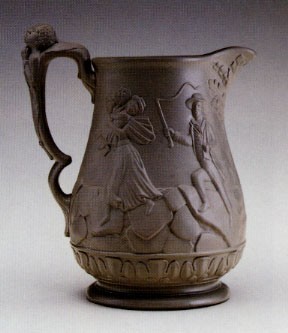

Pitchers, Ridgway & Abingdon, Staffordshire, 1855. Colored stoneware and parian. H. of tallest: 8". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The molded images are taken from two scenes in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, with the side shown depicting a slave auction. The three-dimensional handle shaped as a kneeling slave represents nearly seventy years use of that poignant image since the introduction of Wedgwood’s medallion in 1787.

Reverse of the jug illustrated in fig. 47.

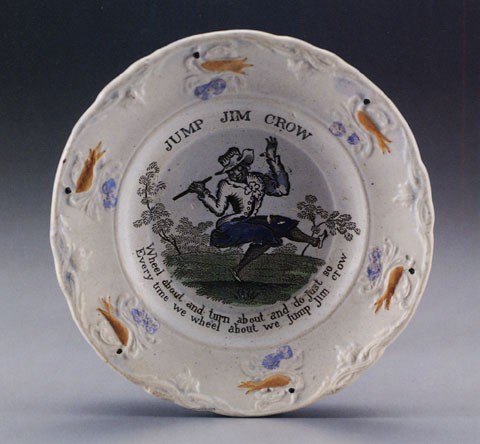

Child’s plate, England, ca. 1850. Whiteware. D. 5 3/8". (Collection of the author; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Enamel-colored black transfer print “jump jim crow,” with molded rim.

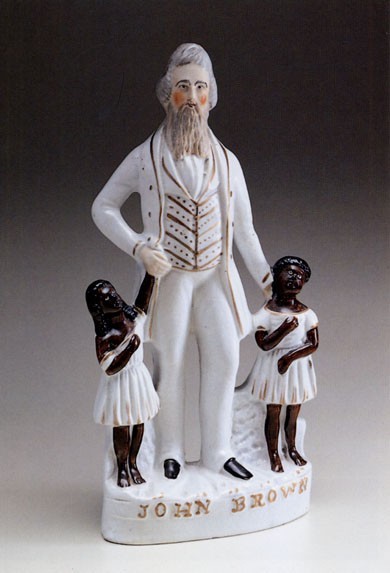

Figure, Staffordshire, ca. 1860. Whiteware. H. 11". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The molded, hand-enameled figure of militant abolitionist John Brown contrasts sharply with the diminutive, adoring children.

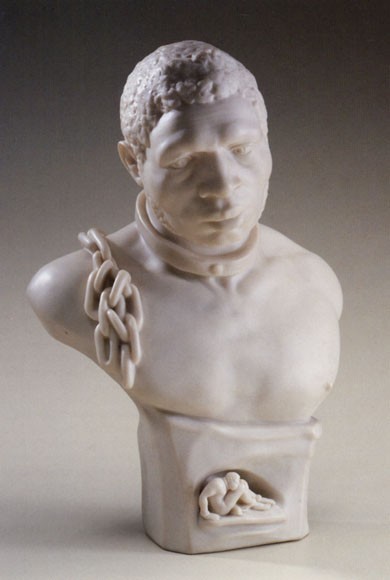

Bust, Copeland, Staffordshire, 1864. Parian. H. 9 3/4". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This powerful sculptural expression of a chained slave with collar is among the most artistically-proficient and dramatic images of slavery. A confined full-body slave is represented in a recess on the base. The base is marked “Published May 1, 1864 Copeland.”

In February 1788 Josiah Wedgwood sent the president of the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery “a few Cameos on a subject which is daily more and more taking possession of men’s minds on this side of the Atlantic as well as with you.” Accordingly, Wedgwood added “it gives me great pleasure to be embarked on this occasion in the same great and good cause with you, Sir.” The president of the Pennsylvania society was Benjamin Franklin and the “great and good cause” to which Wedgwood referred was the eradication of human bondage.[1]

The jasperware cameos featured the image of a kneeling, black male slave in chains, a design modeled by William Hackwood and adopted by the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade in 1787 for use in its seal (fig. 1). Wedgwood reproduced the image for the founding of the society and donated the cameos to friends and supporters of the cause.[2]

Wedgwood’s dedication to the antislavery movement developed in the context of prevailing Enlightenment influences. He was closely associated with the Lunar Society of Birmingham, composed of men who shared not only a passion for scientific inquiry but also an interest in social and industrial progress. In 1773 society member Thomas Day published The Dying Negro, an epic poem which may have influenced Wedgwood to become actively involved in suppression of the slave trade.

Thomas Clarkson, one of Britain’s leading abolitionists, indicated how the cameos came to be widely disseminated, publicly visible, and a valuable means of promoting the cause (fig. 2). Women, he reported, had them incorporated into bracelets and hairpins so that eventually “the taste for wearing them became general.” The medallions were also set into boxes, and artisans applied the design to a variety of objects including plates, pitchers, patch and snuff boxes, tea caddies, and tokens (fig. 3). “Thus fashion,” observed Clarkson, “which usually confines itself to worthless things, was seen for once in the honourable offce of promoting the cause of justice, humanity and freedom.”[3]

African Images in English Society

Promoting the cause was a task made all the more diffcult, however, by the less than complimentary manner in which blacks were often portrayed in Anglo-American culture. Much of the negative attitude derived from the specific and powerful meanings that English society associated with the word “black” well before the introduction of Africans to England in the 1550s. Some pre-sixteenth-century definitions in the Oxford English Dictionary including “deeply stained...dirty, malignant...foul, iniquitous, atrocious, horrible, wicked,” exemplify decidedly negative connotations. Consistent with this view, Queen Elizabeth I sought to banish blacks from the kingdom in 1601, declaring her “discontent...at the great numbers of negars and Blackamoors which...are crept into this realm.”[4] But the very fact that the population of Africans (whose immigration to the country was by no means voluntary) was increasing suggests that not everyone in England was repulsed by their presence. In fact, blacks were gaining popularity among the English gentry as domestic servants and status symbols, a fashion trend that continued throughout the seventeenth and most of the eighteenth centuries.

Contemporary paintings of English aristocrats often included black attendants, generally ascribing to the Africans a status comparable to that of household pets. These graphic representations generally depicted the servant either gazing earnestly at his or her white master or mistress or as a “mute background figure...unnoticed and unacknowledged...barely more than a blob of black paint, a shadowy figure with no personality or expression.”[5] The black servants portrayed in mid-eighteenth-century Staffordshire figural groups typically display unflattering, almost apelike characteristics: protruding lower jaw, low and massive brow, and exceptionally long arms (fig. 5). This diminished image of the black servant was further reinforced by the mass production of the late eighteenth-century transfer print of The Tea Party in which the features of the pet dog appear to have been rendered with greater care than those of the black houseboy (fig. 6).

Africans in English society appear to have been as much objects of curiosity and fascination as disdain, however. In addition to their appearance on trade cards, maps, and coats of arms, figures of African adults and children were employed on signboards, ubiquitous in eighteenth-century London, to advertise occupations as varied as those of cheesemongers, haberdashers, and oilmen.[6] The particular motifs of the blackamoor’s head (usually in profile) and the black boy (or, occasionally, the black girl) have been identified as characteristic of the linen drapers and pewterers, respectively. Both designs also were widely used by tobacconists and public houses, or pubs, as mention of the “Black Boy in Bucklersbury” tavern in Ben Jonson’s early seventeenth-century play Bartholomew Fair suggests (Act 1, scene 1).[7] Such images may not have been quite as omnipresent in America, but references such as the 1735 newspaper announcement of a Philadelphia merchant relocating to Market Street under “the sign of the Black Boy” indicate that they certainly existed (fig. 4).[8]

While many of these representations were patronizing to various degrees, not all were inherently derogatory or condescending. The use of African images in conjunction with heraldic crests conveys a sense of dignity, even nobility, conforming to contemporary European notions of the “noble savage” (figs. 7-10). But whether portrayed as pet-like servants, quaintly exotic figures, or noble savages, such depictions of Africans in Anglo-American popular culture all failed to convey the harsh and often brutal realities of chattel slavery in America and the West Indies (fig. 11).

Abolition Images

To persuade others of the rightness of their cause, abolitionists first had to make a convincing case for the essential humanity of black people. Perhaps it was for this reason that the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade chose the specific wording “Am I Not a Man and a Brother” for use on its seal and, consequently, Wedgwood’s cameo. Before Englishmen and Americans could regard slaves as brothers, they would first have to consider them human beings.

In the late eighteenth century, however, evangelical and Enlightenment influences gave rise to a growing impulse toward humanitarianism and a mood of sentimentality that produced greater empathy with the slave’s plight.[9] Among the foremost literary efforts was William Cowper’s seven-stanza poem The Negro’s Complaint, cited by Clarkson as an influential popular work that spread throughout England “where it was sung as a ballad; and where it gave a plain account of the subject, with an appropriate feeling, to those who heard it.”[10]

Employing a combination of visual imagery and verse, nineteenth-century British potters produced a variety of wares designed to arouse sympathy for the slave. Many themes were evoked, including depictions of the anguish of family separation and graphic portrayals of slavery’s horrors (figs. 12-16). Other ceramic pieces reveal a more subtle approach to promoting the abolitionist cause. One strategy was to incorporate the message into the familiar, traditional form of the rhyming couplet commonly applied to English hollow ware (fig. 17). A popular verse that has its origins in the eighteenth century but was employed on later nineteenth-century earthenware proclaims:

Health to the Sick

Honour to the Brave

Success attend true Love

And Freedom to the Slave

Certain designs used by both British and other European potters not only aroused sympathy for slaves but also goaded supporters of the abolitionist cause to positive action. One option open to the average consumer was to refuse to purchase goods produced by slaves. William Fox’s 1791 pamphlet, An Address to the People of Great Britain on the Propriety of Abstaining from West India Sugar & Rum, apparently provided the impetus for just such a campaign.[11] This early example of what came to be known as a “boycott” in the late nineteenth century is manifest in the injunction enameled on early nineteenth-century earthenware and bone china not to buy West Indian sugar that had been brought to market through the exploitation of slave labor (figs. 18, 19).

How persuasive were the boycott messages and the broader campaign? In a January 1792 letter to Wedgwood, Thomas Clarkson wrote that he had not traveled anywhere the Fox pamphlet “had been for any time in circulation, where it had not produced an astonishing effect.”[12] That result, according to the abolitionist, consisted not only of “disposing the minds of such persons toward our cause, as we ourselves should have otherwise never reached,” but also of significantly altering the buying habits of English consumers (fig. 20). In a postscript, Clarkson indicated that “25,000 Persons have left off Sugar & Rum” and that the “Sugar Revenue by Report has fallen off 200,000£ this Quarter.”[13] Years later the abolitionist stated that among those “who had made this sacrifice to virtue...were all ranks and parties. Rich and poor, churchmen and dissenters.” Clarkson estimated that the number of individuals in England who had forsworn the use of sugar as a matter of moral conviction amounted to “no fewer than three hundred thousand persons.”[14]

Popular feeling eventually turned in favor of the abolitionists, but due largely to war with France and slave revolts in the West Indies in the late eighteenth century, it was some time before Parliament adopted legislation ending the slave trade and decades more until it abolished slavery in the British colonies altogether. Although the Commons voted to end the trade in 1792, full passage of the measure was blocked in the House of Lords where the influence of the West Indies plantation lobby was strong. Nevertheless, Parliament managed to severely restrict the trade in 1806 and abolished it the following year (figs. 21, 22).

A number of ceramics honoring the acts of 1806–1807 were produced, although they generally celebrate the statutes in an oblique way. Reminiscent of the portraits of African servants gazing ardently at their aristocratic English masters, the transfer print on a Liverpool creamware jug depicts a regal white female seated on a pedestal in a sheltering pose above two blacks with the legend “Britannia Protecting the Africans” printed beneath (fig. 23). This jug offers a glimpse of how ceramic manufacturers were responding to currents in the British social and political arena and the extent to which the slavery issue had become a cause célèbre in England. Among the most important ceramics produced at the time of the abolishment of the slave trade is a Staffordshire figure who gratefully declares “BLESS GOD THANK BRITON ME NO SLAVE” (fig. 24).

Although legislation prohibiting the slave trade protected free Africans from future abuses by British slavers, it did little to alleviate the suffering of those already in bondage. As former United States president and antislavery legislator John Quincy Adams reflected in 1838, “human reason cannot resist, nor can human sophistry refute the conclusion, that the essence of the crime consists not in the trade, but in the Slavery.”[15] Recognizing the diffculty of overcoming the power of the West Indian lobby all at once, abolitionists sought to end slavery in stages: first by outlawing the slave trade, then allowing for a period of adjustment and retrenchment, and, finally, by abolishing slavery itself. That time came in 1833 when Parliament voted to abolish slavery throughout the British empire, effective August 1 the following year. The legislation passed with a proviso that those currently enslaved above age six would undergo an additional term of indentured apprenticeship before complete freedom would be granted. Full emancipation actually took effect on August 1, 1838.[16]

The deliverance of 1838 consummated what has been described as England’s “St. Paul-like conversion” from the nation responsible for the enslavement of more Africans than any other to one that styled itself a defender and liberator of blacks in bondage.[17] Conforming to the theme expressed on earlier wares, British artisans produced a variety of decorative pieces commemorating the empire’s newly legislated benevolence. A commanding figural group features an exultant freed slave standing next to Britannia over broken shackles and a discarded whip (fig. 25). The skyward gaze of the liberated slave in all these pieces as well as the Bible at the feet of Britannia also suggest, however subtly, the machinations of a power higher than even England, a sentiment conveyed more explicitly by the “bless god” invocation in the previously mentioned figure’s book (fig. 26).

England’s motivation in ending slavery and the slave trade was not entirely selfless. “Freedom,” as James Walvin has pointedly observed, “meant free trade, free labour, the free movement of capital, in effect the freedom of an ascendant British economy to invest, exploit and control.”[18] An intriguing commercial corollary to the antislavery movement, and one that assumed greater importance after the passage of British abolition legislation, was the issue of international free trade. Intimately associated in some quarters with the struggle for human emancipation itself, the principle of free trade as it related broadly to slavery was articulated in a 1788 speech to Parliament by William Wilberforce. The prominent English abolitionist and politician provided both the moral and economic rationale for unrestricted commerce when he introduced a motion to end the slave trade by enjoining his colleagues to “make reparation to Africa as far as we can, by establishing trade upon true economic principles, and we shall soon find the rectitude of our conduct rewarded by the benefits of a regular and growing commerce.”[19]

A printed white earthenware plate offers a graphic illustration of Wilberforce’s vision (fig. 27). Entitled “Brotherhood and Free Trade with all the World,” the design represents an ingenious twist on the familiar scene of the African native and slaver in the foreground, slave ship behind. In this image the design elements are similar, but the white and black figures are clearly portrayed as equals, shaking hands and jointly planting a banner of freedom on the shore of a symbolic new world. The three-masted vessel in the background no longer signifies the evils of the slave trade but the promise of unimpeded commerce that the legend below proclaims. Another plate offers a less egalitarian and more explicitly self-serving interpretation of the free trade doctrine. Iconic figures representing Asia, America, and Africa—the first two bearing gifts, the last in shackles on bended knee—attend a serene and seated Britannia within the legend “Unfettered Intercourse between all Nations—The Best Security for Abundance and Peace” (fig. 28).

American Abolition

One aspect of the free trade issue of particular concern to American abolitionists pertained to the English corn laws, statutes dating back to the fourteenth century that regulated the import and export of grain. Because they restricted English importation of American wheat while promoting that of cotton, the corn laws induced British consumers to patronize an agricultural enterprise that exploited slave labor at the expense of one that did not. The results, of course, proved injurious to the antislavery cause. As Philadelphia abolitionist Samuel Webb charged in an 1843 letter to his English counterparts, “you buy the slaveholder’s cotton—you hire him to chain, to whip and to work his slaves to death! You stimulate him by your money—by your patronage—by your commerce!”[20]

Webb’s letter serves as a stark reminder that, although England had legislated emancipation a decade earlier, abolitionists were still far from achieving success in the United States. Yet, as early as the late seventeenth century, Americans—especially Quakers and, later, Methodists—had been among the first and most outspoken opponents of slavery. In the 1770s several colonies went so far as to petition the home government to end or restrict the importation of slaves to America, efforts which the royal authorities—ironically in view of Britain’s subsequent moralistic antislavery crusade—rejected. But the colonists soon were confronted with moral inconsistencies of their own when British opponents of the Revolution sought to exploit the contradiction between America’s rhetoric of freedom and its slaveholding. “How is it,” asked Samuel Johnson after the Declaration of Independence, “that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of Negroes?”[21]

Although several states saw fit to abolish slavery within their borders during the first years of the Republic, and Congress, like Parliament, proscribed the slave trade in 1807 (effective the following year), the movement to emancipate slaves in America developed more slowly than in England. Despite the gradual dissolution of slavery in the North and successful legislative efforts such as the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 to restrict its westward expansion, slavery gained a firm foothold in the plantation states of the South.[22] Moreover, the commitment of such prominent activists as Benjamin Franklin notwithstanding, the efforts of the antislavery movement in the United States generally were scattered and ineffectual until the 1830s. The formation of the American Colonization Society in 1817, for example, actually may have done more to hinder than advance the cause. Proposing to transport free blacks from the United States and resettle them in Africa, the movement was opposed by many freedmen who considered America their home and criticized by abolitionists who saw colonization as a thinly veiled attempt to simply remove blacks from the nation altogether.

By the 1830s, however, American antislavery societies were expanding swiftly in number and influence. And in 1837 an event took place that profoundly affected the movement and resulted in the production of the first antislavery ceramics with explicitly American themes. The episode involved two highly charged issues, abolition and freedom of speech, and the fearless determination of newspaper editor Elijah P. Lovejoy to stand firm on both. An ordained Presbyterian minister and editor of a religious publication, the St. Louis Observer, Lovejoy was a somewhat reluctant participant in the abolitionist campaign. A “gradualist” who advocated a slow, cautious approach to emancipation, he occasionally defended slaveholders against what he regarded as false accusations. But in 1835, when antiabolitionist fervor erupted among the local populace, a citizen’s group delivered to Lovejoy a resolution declaring “that the right of free discussion and freedom of speech exists under the constitution, but that...does not imply a moral right, on the part of Abolitionists, to freely discuss the question of slavery....It is the agitation of a question too nearly allied to the vital interests of the slave-holding states to admit of public disputation.” The resolution further condemned abolitionist activities as being “in the greatest degree seditious, and calculated to incite insurrection and anarchy, and ultimately, a disseverment of our prosperous union.”[23]

Bristling at the attempt to silence him, Lovejoy’s response was unequivocal. “I do, therefore,” he wrote, “as an American citizen, and Christian patriot, and in the name of Liberty, and Law, and Religion, solemnly protest against all these attempts...to frown down the liberty of the press, and forbid the free expression of opinion. Under a deep sense of my obligations to my country, the church, and my God, I declare it to be my fixed purpose to submit to no such dictation. And,” he added, perhaps presaging future events, “I am prepared to abide the consequences.” The consequences would be severe. Attacks on the newspaper, including the destruction of his printing press, forced Lovejoy to leave St. Louis in 1836 for Alton, Illinois, where his reception proved no more hospitable. Within a day of its arrival, Lovejoy’s new press had been smashed and hurled into the Mississippi River, acts of destruction which would be repeated no less than four times in little over a year.[24]

In the final episode, Lovejoy was shot to death while defending his press against an angry mob on the night of November 7, 1837. Although the courageous editor barely receives mention in modern histories, John Quincy Adams wrote in 1838 that “the incidents which preceded and accompanied, and followed the catastrophe of Mr. Lovejoy’s death have given a shock as of an earthquake throughout this continent, which will be felt in the most distant regions of the earth.”[25] The events produced “a burst of indignation,” reported the Boston Recorder, “which has not had its parallel in this country since the battle of Lexington in 1775.”[26] Lovejoy’s example inspired many to take up the abolitionist banner including celebrated activist Wendell Phillips, a young firebrand named John Brown, and Ohio attorney William Herndon who, in turn, influenced the views of his friend and law partner, Abraham Lincoln.[27]

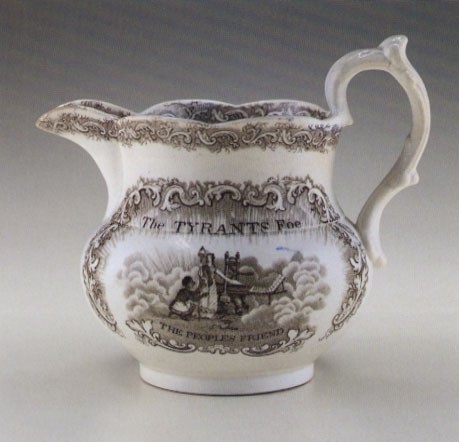

Since Lovejoy became a martyr to proponents of both a free press and the antislavery movement, Staffordshire potters memorialized him in a white earthenware plate featuring design elements symbolic of each (fig. 29). Printed in light to medium blue, the central motif consists of the words of the First Amendment surrounded by a border with alternating cartouches and American eagles. The image in the main cartouche includes a slave kneeling at the feet of Liberty, shackles and whip lying in the foreground, and a printing press behind. Two variations of the inscription exist: “LOVEJOY The first MARTYR to American LIBERTY at ALTON NOV. 7, 1837” and “The TYRANTS Foe The Peoples Friend.” Similar transfers were applied to other forms in tea and dinner services (figs. 30, 31). Donated by British abolitionists and shipped to New York to raise money through their sale for the American antislavery movement, the pieces became extremely popular, so much so that forgers manufactured and passed off as originals reproductions fabricated in the late nineteenth century.[28]

The images on the First Amendment plate are almost as noteworthy for an element they omit as those they include. Since many of the antislavery pieces featuring the kneeling slave also contain some reference to God or religion, we might reasonably expect to see one here, particularly in view of Lovejoy’s ordination as a minister and frequent invocations of God and church in resisting censorship. Certainly, precedent existed for the use of such imagery or messages in antislavery publications. Lovejoy’s contemporary and fellow abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, for example, prominently featured the image of Jesus Christ freeing a kneeling slave while rebuking a slavemaster in the masthead of his antislavery newspaper, The Liberator.

The role of religion in the debate over slavery was an ambivalent one. Ecclasiastical authorities, some perhaps less sensitive to moral than economic concerns, were by no means unanimous in supporting emancipation. Responding to a need to classify slaves for commercial purposes, England’s Solicitor-General had determined in 1677 “that negroes ought to be esteemed goods and commodities within the Acts of Trade and Navigation.”[29] Over fifty years later, British legal authorities determined that baptizing blacks did not change their status as slaves. Shortly thereafter, the Bishop of London endorsed both judgments, declaring that “Christianity, and the embracing of the Gospel, does not make the least alteration in Civil Property, or in any of the Duties which belong to Civil Relations.”[30] Still, Christian clergymen could not easily dismiss the apparent contradiction of preaching love for fellow men while sanctioning their enslavement.

Advocates of slavery based their arguments mainly on “scientific truths” allegedly confirming black inferiority and biblical passages that appeared to justify human bondage.[31] South Carolina physician Josiah Nott offered an example of the former in an 1844 essay in which he maintained that “There is a marked difference between the heads of the Caucasian and the Negro, and there is a corresponding difference no less marked in their intellectual and moral qualities....Their intellects are now as they have always been, as dark as their skins.”[32] Defenders of slavery found further justification in biblical references to human bondage and, in particular, the apparent sanction of the institution by St. Paul who counseled: “Let each one remain in the calling in which he was called. Were you called as a slave? Do not let it bother you....Let each one, brothers, remain with God in the state in which he was called.”[33]

Slavery proponents still felt obliged to reconcile pious notions of love for all mankind with the subjugation of other human beings, however. They managed to do so by fusing assumptions of black inferiority with a version of Christian benevolence into a concept that has come to be known as “evangelical stewardship.” Under this scheme, as expressed by a Virginia Baptist minister, “The guardianship and control of the black race, by the white, is an indispensable Christian duty, to which we must yet look, if we would secure the well-being of both races.”[34] Although no ceramics explicitly advocating slavery have yet come to light, some are decidedly ambiguous on whether the duty of religion should have been to oppose bondage or encourage slaves to be content with their lot. A child’s pearlware plate, for example, presents the image of a kneeling black with a group of peers in prayer behind (fig. 32). Taken from a color sheet by William Jolly and published by William Darton, Jr. in 1812, the inscription extolls the virtues of “MY BIBLE,” but makes no mention of either slavery or emancipation.[35] Similarly, from a series of child’s plates called “Flowers that Never Fade,” one entitled “Piety” depicts two young white girls giving alms to a dark-skinned beggar within the inscription,

While God regards the wise and fair

The noble & the brave, He listens

To the beggar’s prayer, and the poor Negro slave.[36]

Little ambiguity is evident, however, in the ceramics that combine familiar antislavery imagery with relevant biblical text. Passages from the Old Testament especially were employed to draw the analogy between the suffering of the ancient Hebrews in Egypt and during the Babylonian Captivity and that of enslaved Africans in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. To accompany the text, some ceramic producers favored images of either the kneeling female or a slave mother holding her baby. A slender-necked vase (figs. 33, 34 ) displays the figure of a kneeling slave in chains on one side and, on the other, a verse from Ezekiel (22:29), a Jewish prophet during the sixth-century B.C.E. Babylonian exile:

The people of the land have

used oppression and

exercised robbery, and

have vexed the poor and needy

Not included in the transfer are the ensuing lines of scripture in which God, speaking through Ezekiel, admonishes, “I have therefore poured out My indignation upon them; I will consume them with the fire of My fury. I will repay them for their conduct.”[37] The implied threat to slaveowners would have been clear to the many in nineteenth-century England and America familiar with the biblical text. To those less conversant in scripture, the New Testament legend on the base of a graceful sauceboat in the shape of a nautilus shell (fig. 35) delivered the same message more explicitly: “And the nation to whom they shall be in bondage will I judge.”[38] A similar plate (fig. 36) combines the slave mother and baby image with Old Testament quotations from Isaiah 38:14 (“I am oppressed undertake for me”) and Lamentations 5:5 (“I labour and have no rest”) as well as the promise of Christian redemption:

As borrowed beams illume our way

And shed a bright and cheering ray

So Christian Light dispels the gloom

That shades poor Negro’s hapless doom.[39]

The message conveyed by a drabware cup and saucer is somewhat more obscure (fig. 37). The transfer print on the cup is that of the familiar female slave in chains (fig. 39), but the figure on the saucer, though similar, has broken chains and holds a Bible (fig. 38). Published in London in 1828, the image derives from an engraving which faces the title page of a pamphlet by Mary Dudley entitled Scripture Evidence of the Sinfulness of Injustice and Oppression. Predating English emancipation laws by half a dozen years, the engraving also bears the caption “This Book tell Man not to be cruel; Oh that Massa would read this Book,” suggesting a liberation from bondage perhaps more spiritual than literal (fig. 40).[40]

The pamphlet’s date of publication is also significant in that 1828 represents the year in which English abolitionists first introduced the kneeling female slave image as a counterpart to the male figure that Wedgwood had popularized. American activists soon adopted the motif as well. Newspaper editor Benjamin Lundy used it in the The Genius of Universal Emancipation as early as 1830 followed by William Lloyd Garrison in The Liberator shortly thereafter.[41] In 1837 the American Anti-Slavery Society in New York commissioned a New Jersey firm to issue copper tokens featuring a kneeling slave with the legend “AM I NOT A WOMAN & A SISTER” (fig. 41).[42] The appearance of the female icon in Britain and the United States symbolized not only a growing awareness of the special vicissitudes that women suffered under slavery as victims of sexual exploitation but also recognition of the prominent role that women were playing in the antislavery movement.

That part was a singular one. Citing, among other evidence, a 1787 antislavery letter to a Manchester, England, newspaper that unequivocally associated the “Fair Sex” with the “Qualities of Humanity, Benevolence, and Compassion,” historian Clare Midgley has concluded that “those moral qualities on which abolitionist commitment was based were...from the outset identified as especially feminine in nature.”[43] The gender attribution of these traits combined with the development of the “separate spheres” ideology of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries—a philosophy that specified business and political life as the male domain and domestic and family life as the female realm—to create unique functions for women within the antislavery community. Although women generally were barred before the 1830s from serving on abolitionist society committees, speaking out in public, or signing petitions, their decisions as the individuals primarily responsible for household purchases and consumption were critical to the success of such vital initiatives as the sugar boycott and abstention campaigns.[44]

Women also contributed by organizing and procuring goods for antislavery bazaars held to promote and raise funds for the cause. Items sold at the fairs, some produced by the women themselves, included ceramics, handicrafts, tokens, and textiles which bore images of kneeling male and female slaves.[45] To enlighten local communities and encourage attendance, fair managers displayed antislavery slogans on the walls of bazaars and on signs directing the public to the sites. Some of these, such as “Remember them that are in bonds,” corresponded to maxims transfer printed on antislavery ceramics (figs. 42, 43).[46]

As profoundly as women influenced the antislavery movement, so, too, did the movement affect them. Advocating on behalf of oppressed members of their sex could not help but cause women to reflect on the gender inequalities of their own societies. As early as the 1790s, some, including Mary Wollstonecraft (who later wrote the novel Frankensteinunder her married name Mary Shelley) were comparing their status in England to that of slaves and lamenting that few had “emancipated themselves from the galling yoke of sovereign man.”[47] Even within the movement itself, female adherents had to tackle the “woman question,” the debate over whether to permit the appointment and seating of women delegates at antislavery conventions.

The controversy came to a head in 1840 when female members of the American Anti-Slavery Society, who had already won the issue at home, were denied seats as delegates at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London. Despite the setback, the leader of the American society, William Lloyd Garrison, concluded that the convention had “done more to bring up for the consideration of Europe the rights of women, than could have been accomplished in any other manner.” And, looking back on the event a half century later, leading feminist Elizabeth Cady Stanton (who had attended the London conference on her honeymoon) declared that it “stung many women into new thought and action” and gave “rise to the movement for women’s political equality both in England and the United States.”[48]

Although the prevailing “separate spheres” ideology generally prevented them from assuming highly visible roles in promoting emancipation, some women exerted significant influence through their writings. These included not only those previously mentioned but a number of others, most notably Harriet Beecher Stowe who caused an international sensation with the publication of her novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, in 1852. Practically an instant best seller in the United States and England, the book’s huge commercial success induced potters to manufacture a plethora of items transfer printed with scenes from the text (some with captions in French and German) and even an image of the author herself (figs. 44-46).

Probably the most distinctive pieces comprise a series of molded stoneware pitchers (figs. 47, 48) in various sizes produced by the Staffordshire firm of Ridgway and Abington, potters renowned in their time for “their very zealous...praiseworthy, and...successful efforts to improve the character of modelled ornament.”[49] The jugs display two compelling episodes from the novel: the slave auction and fugitive slave Eliza escaping with her baby across the ice floes of the Ohio River. The precise source for each image is uncertain, but the auction scene is similar to several period print renditions. The depiction of Eliza on the ice most closely resembles the cover illustration of an undated but contemporary piece of sheet music titled “The Slave Mother.”[50] In addition to the scenes on either side, the jug handle is decorated with the head and clasped hands of a slave (presumably Uncle Tom) in prayer, reminiscent of Wedgwood’s cameo figure. Some of the pitchers are stamped on the base with a maker’s mark and production dates as early as 1853, just one year after the book’s publication. In addition to their artistic talents and technical skill, Ridgway and Abington, like other Staffordshire potters, were recognized for their ability to anticipate and react swiftly to public demand.[51]

Controversial in the 1850s, Uncle Tom’s Cabin remains so today. Although some have praised Tom as a model of Christian faith, forbearance, and humility, others have disdained the character as excessively meek and docile. In the context of the mid-nineteenth century, Tom was an admirable figure, however, especially when compared with antiabolitionist caricatures of blacks that had been circulating in American society for several decades. In the wake of antislavery legislative successes, satirical broadsides that portrayed blacks graphically and in farcical text as “apish inferiors of whites” began to appear in the United States as early as 1815. Such images prefigured the minstrel show in which white performers in blackface diffused and perpetuated black stereotypes that lasted well into the twentieth century.[52]

Those stereotypes conform substantially to the figure of Sambo, “the typical plantation slave” defined by historian Stanley Elkins as “docile but irresponsible, loyal but lazy, his behavior...full of infantile silliness.”[53]This symbolic character is implicit in the design of a whiteware plate entitled “JUMP JIM CROW,” featuring a dancing black and a short rhyme describing his jig (fig. 49). The transfer print refers specifically to a white minstrel, Thomas Dartmouth Rice, who performed in blackface as Jim Crow at the Surrey Theater in England in 1836.[54] In his landmark study on late nineteenth- and twentieth-century American race relations, historian C. Vann Woodward maintains that “the origin of the term ‘Jim Crow’ applied to Negroes is lost in obscurity.” Yet Woodward’s identification of Rice as creator of a song and dance called “Jim Crow” in 1832 suggests that the minstrel character and the ceramic image represent two of the earliest documented uses of the term that would become synonymous with the system of legal and de facto discrimination against blacks that prevailed throughout much of the American South in the century following Reconstruction.[55]

While it is tempting to dismiss such images as the products of racist minds, patronizing attitudes toward blacks were not restricted to slavery’s defenders. Throughout the first half of the nineteenth century and even as the Civil War approached, the good intentions but condescension of some associated with the antislavery movement were apparent in various print and ceramic productions.[56] Reminiscent of eighteenth-century portraits of English aristocrats striking a benevolent and omniscient pose above the adoring gaze of their black servants and later ceramics featuring Britannia as protector and defender of Africans, a circa 1860 Staffordshire figure group features militant abolitionist John Brown affecting a similar stance with two black children (fig. 50).

Though sympathetic to the goals of emancipation, such creations nonetheless failed to grant blacks a full measure of humanity. The egalitarian sentiment was never entirely absent, however. Just as some early ceramic pieces portrayed blacks with sensitivity and without prejudice, so, too, does a remarkably realistic parian bust of a chained and collared slave produced by the Staffordshire firm of Copeland in 1864 convey the qualities of dignity, strength, and intelligence (fig. 51). The slave’s eyes also reveal a deep sorrow based, it seems, not just on the suffering of an individual lifetime but the collective anguish of generations past and, perhaps, future as well. For, despite the ebullient optimism of Josiah Wedgwood’s letter to Benjamin Franklin over seven decades earlier, freedom for the slave had yet to be achieved in America. And, even though Union victory in the Civil War would soon bring about emancipation, over a century of desperation and struggle would yet ensue before the descendants of African slaves might enjoy full equality under the law.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am indebted to Chipstone Foundation director Jonathan Prown, and to Ceramics in America journal editor Robert Hunter for reviewing and constructively commenting on this essay, and also to George Miller for providing me with a copy of his important, 1985 contribution to The American Neptune. I am also eternally grateful to Sir David and Lady Burnett who enabled me to work with their collection of ceramic sherds from London’s Hays Wharf properties, of which Sir David was Chairman and C.E.O. and from which I have learned so much.

The Selected Letters of Josiah Wedgwood, edited by Anne Finer and George Savage (London: Cory, Adams, and Mackay, 1965), p. 311; Robin Reilly, Josiah Wedgwood 1730–1795 (London: Macmillan, 1992) p. 287.

Reilly, Wedgwood, p. 286.

Thomas Clarkson, The History of the Rise, Progress, and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave-Trade by the British Parliament (1808; reprint, London: Frank Cass & Co., 1968), p. 192.

David Dabydeen, Hogarth’s Blacks: Images of Blacks in Eighteenth-Century English Art (Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press, 1987), pp. 21–26. See also Hugh Honour, The Image of the Black in Western Art, vol. 4, From the American Revolution to World War I, part 1, Slaves and Liberators (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1989).

Dabydeen, Hogarth’s Blacks, p. 18.

Ibid.

Ambrose Heal, The Signboards of Old London Shops: A Review of the Shop Signs employed by the London Tradesmen during the XVIIth and XVIIIth Centuries (New York: Benjamin Blom, Inc., 1972), pp. 21–22. Jacob Larwood and John C. Hotten, The History of Signboards, from the Earliest Times to the Present Day, 6th ed. (London: John C. Hotten, n.d.), p. 432. Preface dated June 1866.

Phillip Lapansky, “Graphic Discord: Abolitionist and Antiabolitionist Images” in The Abolitionist Sisterhood: Women’s Political Culture in Antebellum America, edited by Jean Fagan Yellin and John C. Van Horne (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1994), p. 216.

Winthrop D. Jordan, The White Man’s Burden: Historical Origins of Racism in the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982), pp. 142–43; Betty Fladeland, Men and Brothers: Anglo-American Antislavery Cooperation (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1972), p. 13.

Clarkson, Abolition of the African Slave-Trade, pp. 190–91.

William Fox, An Address to the People; Correspondence of Josiah Wedgwood 1781–1794 (Didsbury, Manchester, Eng.: E. J. Morten Ltd, 1906), 3: 183.

Ibid., p. 183.

Ibid., pp. 184, 186.

Clarkson, Abolition of the African Slave-Trade, pp. 349–50.

Quoted in Joseph C. and Owen Lovejoy, Memoir of the Rev. Elijah P. Lovejoy (New York: Arno Press and The New York Times, 1969), p. 10.

James Walvin, England, Slaves and Freedom, 1776–1838 (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1986), pp. 165–66. A white earthenware plate is recorded featuring a blue transfer print of a black family celebrating, the flag of liberty waving in the background, all surrounded by the legend, “freedom first of august 1838.”

James Walvin, “British Abolitionism, 1787–1838” in Transatlantic Slavery: Against Human Dignity, edited by Anthony Tibbles (London: National Museums and Galleries on Merseyside, 1995), p. 91.

Ibid., p. 92.

John Pollock, William Wilberforce: A Man Who Changed His Times (Burke, Va.: The Trinity Forum, 1996), p. 16.

Quoted in Fladeland, Men and Brothers, p. 286.

Ibid., p. 25.

William W. Freehling, “The Founding Fathers and Slavery” in American Negro Slavery: A Modern Reader, edited by Allen Weinstein, Frank O. Gatell, and David Sarasohn (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979), pp. 9–13.

David W. Blight, “The Martyrdom of Elijah P. Lovejoy,” American History Illustrated 12, no. 7 (1972): 21.

Ibid., pp. 21–22.

Quoted in Lovejoy, Memoir, p. 12.

Quoted in Henry Tanner, The Martyrdom of Lovejoy: An Account of the Life, Trials and Perils of Rev. Elijah P. Lovejoy (1881; reprint, New York: Augustus M. Kelley, 1971 ), p. 9.

Blight, “The Martyrdom of Elijah P. Lovejoy,” p. 27.

Marian Klamkin, American Patriotic and Political China (New York: Scribner’s Sons, 1973), pp. 102–4; Ellouise B. Larsen, American Historical Views on Staffordshire China (New York: Dover Publications, 1975), p. 242.

Walvin, England, Slaves and Freedom, p. 32.

Dabydeen, Hogarth’s Blacks, p. 119.

The Ideology of Slavery: Proslavery Thought in the Antebellum South, 1830–1860, edited by Drew Gilpin Faust (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1981), pp. 10–12.

Josiah C. Nott, “Two Lectures on the Natural History of the Caucasian and Negro Races,” in Faust, ed., The Ideology of Slavery, pp. 232–33.

I Corinthians 7:20–21, 24.

Thornton Stringfellow in Faust, ed., The Ideology of Slavery, p. 136.

Noel Riley, Gifts for Good Children: The History of Children’s China, Part One 1790–1890 (Ilminster, Somerset, Eng.: Richard Dennis, 1991), pp. 244–45.

Ibid., pp. 252, 253.

Ezekiel 22:31.

Acts 7:7.

Tibbles, Transatlantic Slavery, p. 93, Wg. 180.

Clare Midgley, Women Against Slavery: The British Campaigns, 1780–1870 (London and New York: Routledge, 1992), p. 100.

Lapansky, “Graphic Discord,” pp. 205–6.

Russell Rulau, Standard Catalogue of United States Tokens 1700–1900, 2d ed. (Iola, Wisc.: Krause Publications, 1997), p. 91.

Midgley, Women Against Slavery, p. 20.

Ibid., pp. 20–24, 37, 94.

Lapansky, “Graphic Discord,” p. 206; Fladeland, Men and Brothers, pp. 227–28.

Lee Chambers-Schiller, “‘A Good Work among the People’: The Political Culture of the Boston Antislavery Fair” in Yellin and Van Horne, The Abolitionist Sisterhood, p. 20.

Mary Wollstonecraft in Midgley, Women Against Slavery, p. 26.

Fladeland, Men and Brothers, pp. 264–65; Midgley, Women Against Slavery, pp. 160–62.

Quoted from Art Union magazine, December 1846, in Geoffrey A. Godden, Ridgway Porcelains, 2d ed. (Woodbridge, Suffolk, Eng.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1985), p. 164.

Music by George Linley, illustrated by J. Brandard; Stowe-Day Library, Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, Hartford, Conn.

Godden, Ridgway Porcelains, p. 160.

Lapansky, “Graphic Discord,” pp. 216–17.

Stanley Elkins, Slavery: A Problem in American Institutional and Intellectual Life (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1968), p. 82.

Riley, Gifts for Good Children, p. 172.

C. Vann Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow, 3d ed., rev. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980), p. 7.

Lapansky, “Graphic Discord,” pp. 211–12.