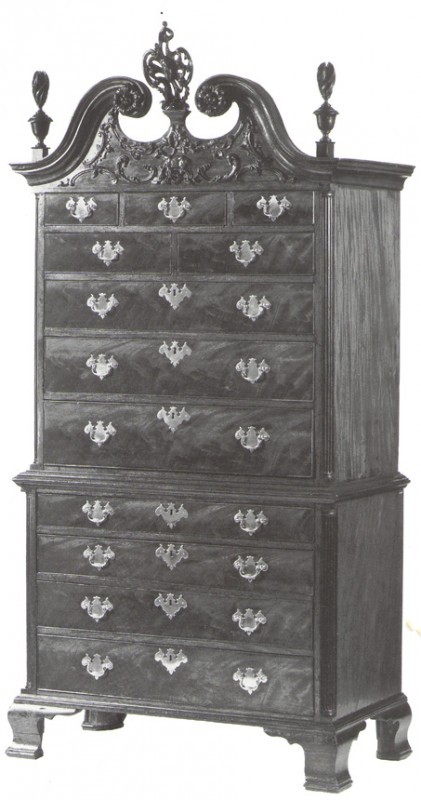

Pretreatment view of the lamb-and-ewe chest-on-chest showing the locations where finish samples were taken, Philadelphia, 1765-1775. Mahogany with white oak, white cedar, and yellow pine. H. 86", W. 42 7/8", D. 22 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, ace. 60.1056.)

Pediment of the chest-on-chest showing the locations where finish samples were taken. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Francis Barlow, engraving for Theophilia, London, 1652. (Courtesy, Chapin Library, Williams College.)

Detail of a carved tablet on a chimneypiece, Sanbeck Park, Yorkshire, England, 1750-1760. (Photo, Bradley Brooks.)

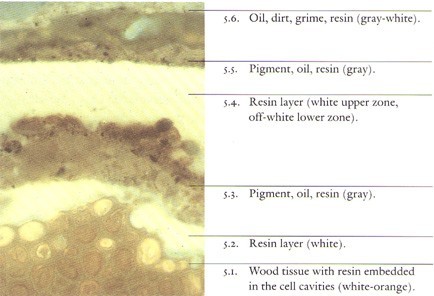

Sample from the scrollboard, average surface thickness 1.8 microns. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.) This sample was taken from a protected area of the scrollboard adjacent to the appliquÈ. Because the six layers represent an extensive finish history that might be complete, this sample was used as a standard for comparisons with other finish samples.

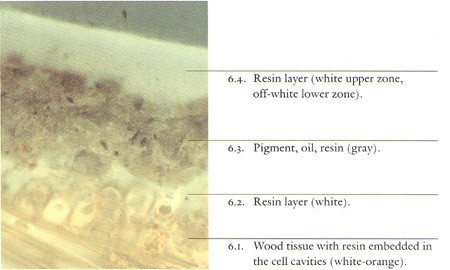

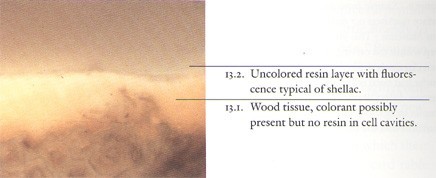

Sample from the rear leg of the ewe, average surface thickness 0.9 microns. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.) The layers in this sample compare favorably with four bottom lavers of the standard (5.1-5.4). There is also a faint film on top of layer 6.4 that could be an oil polish corresponding to laver 5.6. The correlation between the layers on these samples supports the visual observation that the ewe is original.

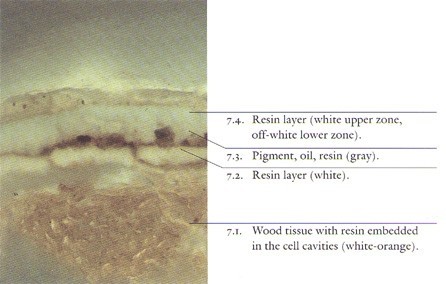

Sample from the right rosette, average surface thickness 0.75 microns. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.) The layers in this sample are consistent with the four bottom layers of the samples in figs. 5, 6. They also match cross sections taken from the left rosette, indicating that both rosettes are original to the chest-on-chest.

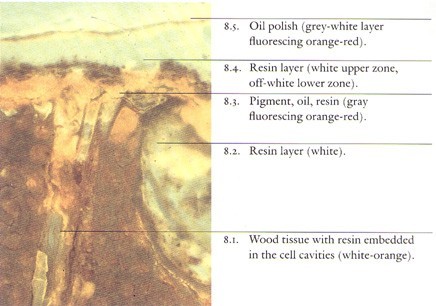

Sample from the left side of the upper case, average surface thickness 0.45 microns. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.) This sample was taken from a protected area on the back edge of the side. A reactive dye was added to this section to cause the oil layers to fluoresce orangered. The surface stratification of samples in figs. 5-7 is repeated with the exception of the uppermost layer (8.5) that corresponds with 5.6 in the standard sample. It is clear from the deep, orange-red fluorescence of layers 8.2 and 8.3 that the original finish included oil mixed with a resin.

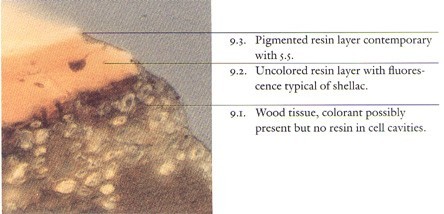

Sample from the cartouche, average surface thickness 0.7 microns. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.) This sample was taken from deep within the carving where it would have been extremely difficult to reach if the cartouche had been refinished. The surface stratification differs dramatically from that of the samples in figs. 5-8, lending support to the statement that the cartouche was added later.

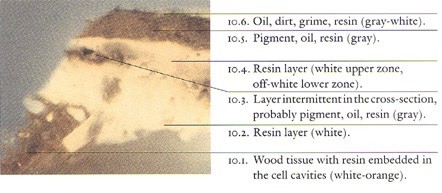

Sample from the flame section of the finial, average surface thickness 1 micron. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.) Although a note in the accession file states that the flames are new, they have a substantial finish history. The stratigraphy is very similar to that of the standard and suggests that the finials are old and probably original (compare with fig. 5). Philadelphia flame finials typically were made in three or four sections. Because individual sections could be lost or broken, a substantial number of period examples survive in a similarly restored condition.

Sample from the turned section of the finial, average surface thickness 0.3 microns. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.) The surface history of this component contrasts with the flame but is similar to that of the replaced cartouche (figs. 9, 10). It may have been added at the same time as the cartouche.

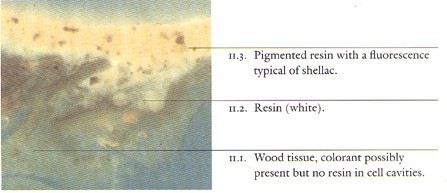

Finial plinth, average surface thickness 0.6 microns. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.) Although this section has a stratification that relates to part of the standard (5.4, 5.6), it is not possible to prove that the plinths are original. They probably are either original and have been refinished, or they are old replacements.

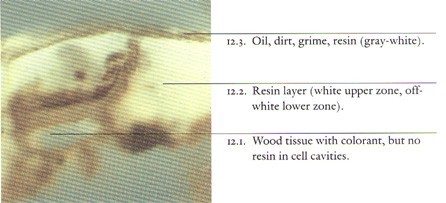

Sample from a scroll volute of the appliqué, average surface thickness 0.2 microns. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.) Samples were taken from areas of the carving which were thought to have been restored. This sample, taken from a scroll volute, has a stratigraphy that corresponds to the first two layers on the replaced cartouche (9.1, 9.2).

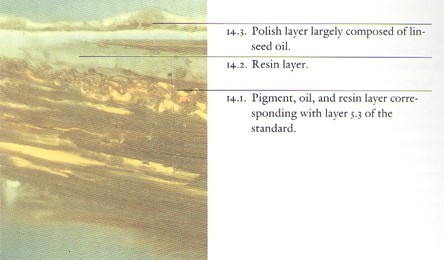

Sample from a drawer front, average surface thickness 0.5 microns. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.) This sample was taken from a section of the drawer less than 5 millimeters from the sample in fig. 15. It shows the finish prior to the enzyme treatment with the oil polish layer intact.

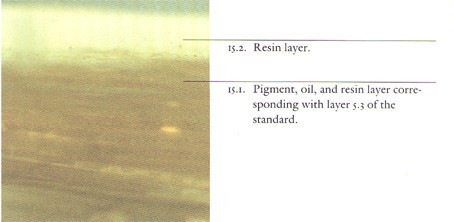

Sample from a drawer front, average surface thickness 0.5 microns. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.) This sample was taken from a section of the drawer less than 5 millimeters from the sample in fig. 14. after the application of the enzyme gel. The oil polish layer evident in fig. 14 has been removed and the underlying coatings left intact.

After-treatment view of the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)

During the last decade, the line separating the furniture conservator and the furniture curator has grown thin as members of both professions have combined information derived from documentary research, scientific analysis, and connoisseurship. Such was the case when the Winterthur Museum's furniture conservation staff examined an eighteenth-century Philadelphia chest-on-chest to determine the originality of its finish and carving (fig. 1) . The "lamb-and-ewe chest," as it has come to be known, was purchased by Henry Francis du Pont from noted antiquarian Joe Kindig, Jr., in June 1940 and subsequently installed in the Port Roval Parlor at Winterthur.[1]

The chest-on-chest had been made between 1765 and 1775 in an as-yet-unidentified Philadelphia cabinet shop. The construction techniques used were typical of lower-echelon London cabinetmakers such as Samuel Bell. The ornament consists of floral rosettes, flame finials, an appliqué portraying a nursing lamb and ewe, and a central cartouche that is remarkably similar to a twentieth-century drawing of a reproduction ornament in Wallace Nutting's Furniture Treasury.[2] In typical Philadelphia fashion, the cabinetmaker attached the rosettes with hide glue and forged nails and made the finials in three parts-flame, urn, and ring-with round mortise-and-tenon joints.

The lamb-and-ewe appliqué sets this chest apart from contemporary Philadelphia case pieces (fig. 2). During the eighteenth century, manv architectural and decorative engravings were available as sources for animal figures. James Stuart's The Antiquities of Athens (1762-1786) and Antoine Desgodets' Les Edifices antiques de Rome (1682) were highly regarded as references for classical detail. George Marshall, who republished Desgodets' work in 1771, noted that the author was "too well known to the professors of architecture, and too much reverenced by all lovers of the art, to require . . . either account or encomium." Stuart's Antiquities included details of the Parthenon, perhaps the most notable source of animal figures in an entablature, and Desgodets' work contained engravings of similar details on other buildings and monuments. The Arch of Titus in Les Edifices featured bulls in high relief, and the Tomb of Bacchus was shown with a sheep that strongly resembles the ewe on the chest-on-chest.[3]

Most eighteenth-century cabinetmakers and carvers had a working knowledge of classical architecture and of the rules of balance and proportion. In the preface to The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker's Director (1754), Thomas Chippendale wrote, "of all the arts which are either improved or ornamented by Architecture, that of Cabinetmaking is . . . capable of receiving as great assistance from it as any whatever."[4] Although Chippendale's statement was true, there were strong classical overtones in all arts and literature. Even simple children's fables and pastorals had representational engravings depicting classical ruins and subjects.

Allegorical illustrations were also an important design source for eighteenth-century artisans. Francis Barlow's engravings of Aesop's Fables (1666, 1687) inspired several designs in London carver Thomas Johnson's One Hundred and Fifty New Designs (1761), one of the most influential English pattern books in Philadelphia. Numerous examples of eighteenth century carving attest to the popularity of Johnson's designs, especially those based on Barlow' s engravings. Moral fables depicted in Philadelphia interiors of the 1760s and 1770s include the "Dog and Piece of Meat" on a chimneypiece tablet from the Samuel Powel House and the "Dog in the Manger," "The Crow, the Deer, the Tortoise, and the Rat," and the "Young Gobbler" on the tablet and frieze panels of the parlor chimneypiece from the Blackwell House (Winterthur Museum). Although the carver of the Blackwell parlor is unknown, the Powel House carving is attributed to Hercules Courtenay who apprenticed with Thomas Johnson before immigrating to Philadelphia.[5] It is reasonable to presume that Courtenay was familiar with Barlow's illustrations, since they often were referred to by his master. At least seven Philadelphia case pieces made between 1765 and 1775 have carved animal forms derived from moral fables. The "Fox and Grapes" high chest and dressing table (Philadelphia Museum of Art) and the "Pompadour" high chest, whose tableau drawer depicts Aesop's "Swan and Serpent" (Metropolitan Museum of Art), are among the most notable. The "Swan and Serpent" appliqué was copied from a design for a chimneypiece tablet on plate 5 of Johnson's New Book of Ornament (1762).[6]

Although the lamb-and-ewe appliqué is reminiscent of the abovementioned carving, the design appears to have been derived from illustrations in pastoral literature rather than a fable. Pastorals were particularly popular in England from about 1650 to 1800, and there were many examples that could have influenced this appliqué. One by Barlow in Edward Benlowe's Theophilia (1652) included a ewe and nursing lamb by a tree-quite similar to the carving on the chest-on-chest (figs. 2, 3), representing "The Sweetness of Retirement, or The Happiness of a Private Life."[7]

It is reasonable to speculate that a pastoral such as Theophilia inspired the carver of the lamb-and-ewe chest since Barlow's illustrations were reinterpreted in design books and available to tradesmen and patrons on both sides of the Atlantic. Pastoral illustration was apparently the source for the carved tablet from a chimney piece in Sanbeck Park- a house built for the Earl of Scarborough during the 1750s in Yorkshire, England. This tablet so closely resembles the lamb and ewe on the chest-on-chest that we wonder if the Philadelphia carver had any direct connection with the designers or carvers at Sanbeck Park (fig. 4).[8] In either case, it is clear that pastoral scenes were the source for the lamb-and-ewe motif.

Having established the general design source for the appliqué, conservators and curators used traditional connoisseurship skills to identify the extent of restoration to the appliqué, rosettes, finials, and cartouche. Discontinuous tool marks and variations in workmanship indicated that parts of the C scrolls were modern and raised the possibility that there were repairs that were unobvious to the naked eye (fig. 2). This was a major issue, given the significance and rarity of the lamb-and-ewe motif. Minor variations in the carving of the rosettes and apparent inconsistencies in the oxidation and finish of the individual sections of the finials also caused concern. The cartouche clearly was out of character with the rest of the carving, and records indicated that it was carved by Jesse Bair of Hanover, Pennsylvania, about 1940.[9]

To refine these gross observations, we examined the surface coating on several parts of the chest-on-chest. Eighteenth-century cabinetmakers used a variety of dyes, stains, and finishes to accentuate the figure and color of wood. The most common surface coatings were simple oil finishes (usually linseed), fixed oil varnishes (oil and solvent mixed with one or more resins), essential oil or spirit varnishes (solvent mixed with one or more resins), and beeswax.[10] Since there was no evidence that the chest was ever completely stripped, scraped, or sanded, we knew that the original finish would be in the cellular structure and on the surface of the wood and that subsequent finishes and/or polishes would form distinct, successive layers -a unique stratigraphy that should be consistent on all of the original components of this piece.

Identifying the predictable surface layers and their components was the next step in determining the originality of carved and structural elements. We used established microscopic techniques to determine the order and nature of the surface stratigraphy: we removed minute surface samples (less than the size of a period on this page) from selected areas and embedded them in a polyester resin; ground each embedded sample at a right angle to the surface plane to expose the finish layers; and examined the cross-sections through a microscope. Using an ultraviolet light source with the microscope, we characterized the material composition of each laver by its fluorescence.[11]

laver photographed the samples illustrated in figures 5-15 through a microscope at 200X magnification.[12] Natural resins, which appear amber colored under normal light, fluoresce orange, yellow, off-white, white, or blue-white, depending on the type and age of the finish. The luminescence of these coatings make them easily identifiable under a fluorescence microscope. Oils, waxes, pigments, and other particulates tend not to fluoresce and remain relatively dark under ultraviolet light. We gained additional information by applying dye to a sample. Reactive dyes can confirm the presence of certain materials, such as oils, by causing them to fluoresce a specific color. The objective, verifiable information provided by these techniques sheds light on the condition and original appearance of the object being studied.

We took finish samples from the scrollboard (or tympanum), the ewe, a rosette, a finial, a side board of the upper case, a drawer front, the cartouche, and areas of carving that appeared restored (figs. 2, 5-15). Our initial objective was to establish a "standard" -a sample with a complete surface history that could be used to evaluate the others. We chose the sample from the scrollboard to be the standard because of the board's status as a structural component and the high probability that its stratigraphy was the most complete (fig. 5). The first (or bottom) four layers of the scrollboard matched those of the ewe, confirming that the lamb and ewe were original components of the appliqué and were original to the piece (figs. 5, 6). These samples also were noticeably different from those taken from areas that had visually been identified as restored (figs. 9, 11). Although new finishes can be made to appear old to the eye, the surface layering that is visible under a microscope would be extremely difficult to simulate.

Comparisons of other samples to the scrollboard sample revealed that most of the carving on the scrollboard was original and that restoration had occurred on the terminals of some C scrolls. The rosettes and finials were more perplexing. A letter in Winterthur's files stated that the finials were contemporary with the circa 1940 cartouche.[13] Samples from the cartouche and parts of a finial established a standard for restored areas and confirmed the fluorescence microscope's capacity to reveal signature configurations of surface layers. Although the rings and plinths of the finials have surface stratifications that differ markedly from that of the scrollboard and matched that of the cartouche, the flames have an old multilayered surface with some similarities to the scrollboard standard (figs. 5, 10). This suggests that the flames are original or that they were added early on. Minor differences in the massing and articulation of the rosettes also caused speculation that they were by different carvers and that one was replaced. Although there was no history of their having been replaced, the vulnerability of such exposed elements warranted further investigation. Cross-sectional examination revealed that the layers on both rosettes matched those of the ewe and scrollboard, confirming their originality (figs. 5-7).

The second focus of our microscopic examination was to determine if any original finish was left on the chest-on-chest and to devise a method to treat its dark and sticky surface. A photograph taken in the early 1950s showed a relatively clear finish, suggesting that the surface had become more opaque over the last forty years. Samples revealed four finish layers on the flat surfaces of the chest. An oil and resin combination appears to have been used for the first (bottom) layer.[14] The cabinetmaker either applied the oil first or it settled out of a spirit varnish. Because these two materials were lodged permanently in the wood, they unquestionably were present in the original finish. This finish would have given the mahogany a highly saturated, glossy appearance.

A late-eighteenth-century finish recipe from the notebook of itinerant Connecticut tradesman Isaac Byington listed ingredients similar to those found in the cell cavities of the samples: "[For] A Varnish for all Colours Take of the best L. [linseed] oil &. finest V. turpentine [Venice turpentine was a common natural resin]. Boyl them together add a little Brandy to it and boil it again. put less or more oil to make it thick or thin.” Byington deemed gloss a worthy objective for a finish and described a particular resin varnish "which stands water and shines like glass." Late-eighteenthcentury paintings show how such a finish probably appeared when new. Charles Willson Peale's portrait of the Cadwalader family painted in 1771 presents John and Elizabeth gathered around a card table on which their daughter Anne is seated. The glossy finished surface of the card table reflects the lace and other details of the child's dress.[15]

Evidence found on the lamb-and-ewe chest indicates that it had a comparable surface. Unfortunately, the remnants of that original layer proved to be discontinuous, largely undetectable to the naked eye, and irretrievable as a continuous presentation surface. The next layer constitutes the majority of the existing finish (see figs. 5.4, 6.4, 7.4, 8.4, 10.4). Because of its position in the surface stratification, its homogeneous nature, and its relatively good condition, we surmised that it was relatively recent but not later than 1940. The more recent outer layers, which tested positive for oil (probably linseed), were sticky, dark, and embedded with dirt, grime, and lint.

This information proved useful for treating the piece. Most of the surface was deemed worth retaining because of the condition and composition of the pre-1940 layers and the remnants of the original surface preserved beneath them. In addition, microscopy had revealed a thin oil layer on the surface that was problematic and of a different composition than the finish laver immediately under it. Based on this stratification, we devised a cleaning system that would remove the disfiguring outer layers without disturbing the underlying zones. Drawing on the technology pioneered by painting conservator Richard Wolbers, we applied an enzyme gel to remove the oil and dirt film on all of the flat surfaces.[16] Figures 14 and 15 graphically illustrate the results of this procedure at the microscopic level.

With the oil film successfully removed, the decision had to be reached as to what additional treatment was necessary. According to Thomas Sheraton, furniture could be kept in good order with nothing more than "a ball of wax and a brush." Astute cabinetmakers like Sheraton realized that wax would help protect a finish and enhance its appearance. Following historical precedent, we applied a mixture of beeswax and carnuba wax, completing the treatment (fig. 16).[17]

The successful study and conservation of this important chest-on-chest was the result of thorough historical research, traditional connoisseurship, scientific analysis, and methodical treatment. It is essential for conservators and curators to combine their expertise. To act as responsible custodians of these objects, we must explore every available avenue of research to ensure that they are properly understood and interpreted and survive intact for others to study.

Edward Benlowe, Theophilia (London: Roger Norton, 1652). Although the appliqué can not be tied directly to a fable, there are striking similarities in composition to some of the fable illustrations. See Francis Barlow, Aesop's Fables with His Life in English, French, and Latin (London: M. Mills, 1687), pls. 31, 61. Edward Hodnett, Francis Barlow: First Master of English Book Illustration (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978), p. 132.

Studies of traditional finishing practices can be found in Robert D. Mussey, "Old Finishes," Fine Woodworking 33, (March/April 1982): 7 and Robert D. Mussey, "Early Varnishes," Fine Woodworking 35, (July/August 1982): 54-57. Resins such as colophony, copal, mastic, sandarac, and shellac were the most common.