Engraving of teapot, earthenware with colored clay ornament; Messrs. Clay and Edge of Burslem, Staffordshire. This drawing appeared in the Art Journal Illustrated Catalogue: The Industry of All Nations, 1851, reprinted as Great Exhibition: London’s Crystal Palace Exposition of 1851 (New York: Gramercy Books, 1995), p. 41. The catalog entry for this teapot reads, “A patented branch of their [Clay and Edge] business is devoted to the ornamentation of similar articles by inlaying clays of various tints, thus producing an indestructible colouring for the leaves and other ornaments.” At the end of Eliza Cook’s tales, she gives a charge to ‘good Summerley and his disciples’ to ‘beautify what thou canst for the people’ and ‘give beauty to poor places’” (p. 46). Summerley was none other than Sir Henry Cole, who had introduced the Journal of Design and Manufacture in 1847 and was one of the chief organizers of the 1851 exhibition.

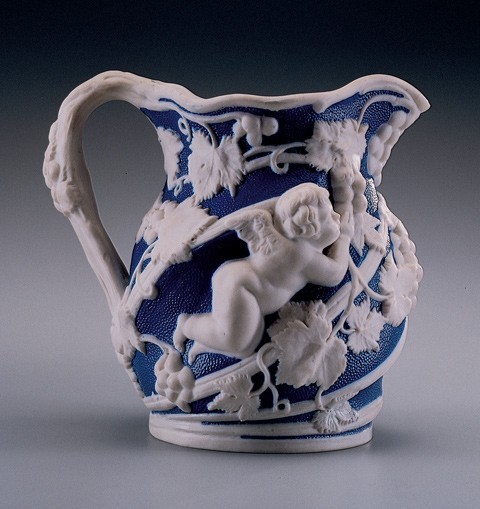

Jug, Minton and Company, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, 1840–1860. Stoneware. H. 6 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The “Felix Summerley” tea-set designed by Cole (discussed above) was produced by Minton and Company. Herbert Minton made a wide array of table and tea wares in earthen, stone, and Parian wares, and he developed many lower-priced colored bodies, including the colors turquoise, blue, and “blue suck.” The jug depicted here is similar to those awarded prizes by the Royal Society of Arts in the late 1840s (Joan Jones, Minton: The First Two Hundred Years of Design and Production [Shrewsbury: Swan Hill Press, 1993]).

Tea bowl and saucer, Ching-tê-chên, China, circa 1730. Hard paste porcelain. D. of saucer: 4 3/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Images of Adam and Eve, while common on English delftwares of the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, are rare on Chinese porcelain. This tea bowl and saucer were enameled in the Netherlands.

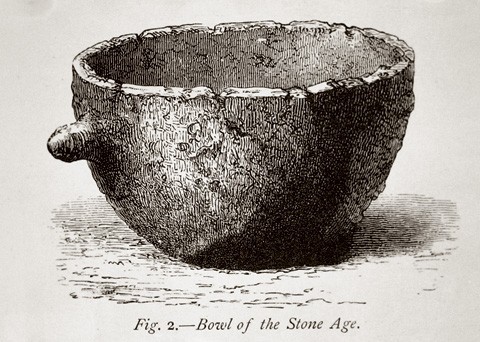

“Cooking pot of the Stone Age” illustrated in Charles Wyllis Elliott, “Unglazed Pottery,” Art Journal, 2nd series, vol. 3 (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1877), p. 117.

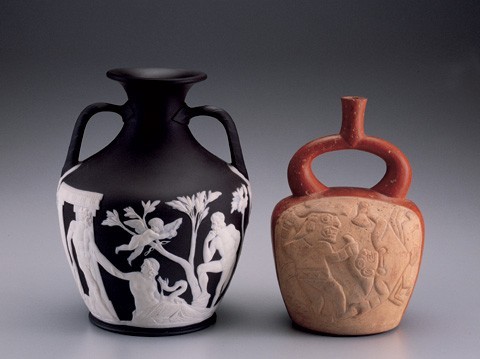

Portland vase and Peruvian stirrup vessel. Portland vase, marked “Wedgwood,” Staffordshire, 1820–40. Jasperware. H. 9 7/8". Stirrup vessel, Moche culture, Peru. H. 8 7/8". Earthenware. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Note the use of relief decoration to depict cultural myths.

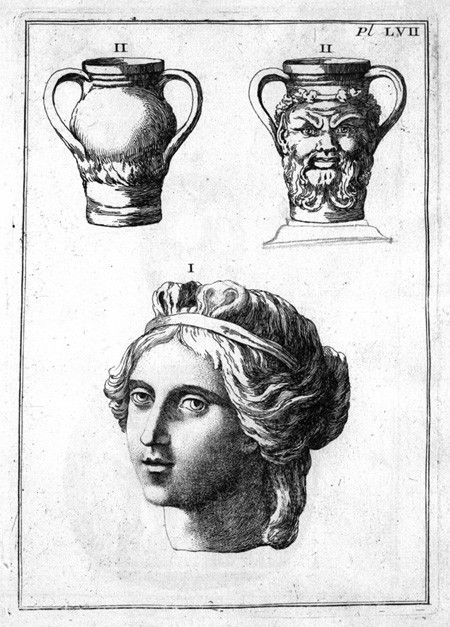

Head cantharus, plate 57, vol. 1. From Anne Claude Phillippe Caylus, comte de, Recueil d’Antiquitiés egyptiennes, etrusques, grecques et romaines, nouvelle edition (Paris: chez Desaint et Saillant, 1761). (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation.) These books, originally owned by Josiah Wedgwood, contain a number of pencil annotations to the engravings. In this instance, note the addition of a base to the front-facing engraving.

Plate, Staffordshire, ca. 1815. Pearlware. D. 8 3/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

A study method for analyzing the plate with American eagle motif illustrated in fig. 7. By answering these questions, the analyst moves outward from an object to the societies that produced and used it. Later, comparisons and relationships with other objects or classes of artifacts are sought. Creative juxtapositions across time, space, and cultures raise new questions again structured in a matrix of time, space, technology, use, value, and aesthetics—and refine these answers.

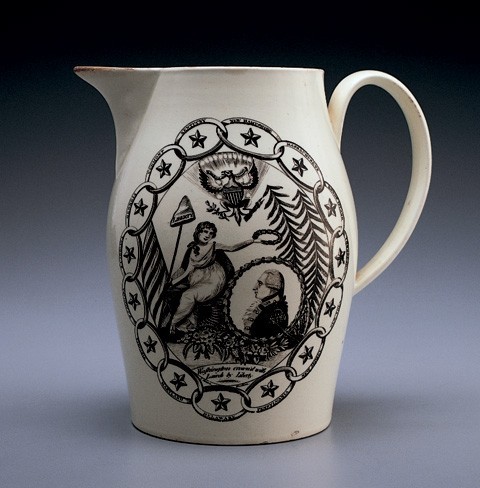

Jug, Shelton, Staffordshire, 1803–1805. Creamware. H. 7 3/4". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dish, James and Ralph Clews, Staffordshire, ca. 1825. L. 9 1/2". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Landing of Lafayette.

Dish, Joseph Stubbs, Burslem, Staffordshire, 1822–1835. White earthenware. L. 16 3/4". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of importer’s mark for Ludlow and Co. of Charleston, South Carolina, on the reverse of dish illustrated in fig. 11. (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

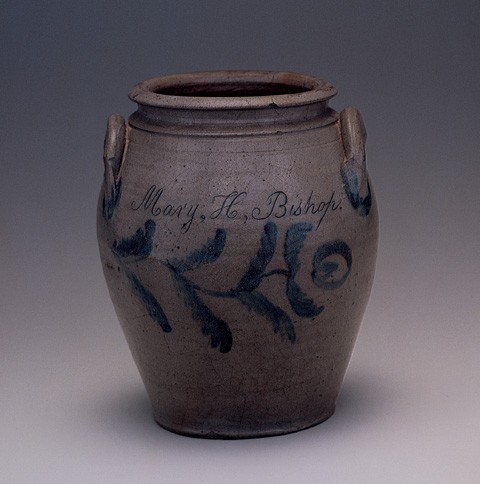

Jar, eastern Virginia, 1840–1860. Stoneware. H. 9 1/4 ". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The cobalt decoration and the added incised inscription of “Mary Bishop” is atypical of the utilitarian nature of these common vessels made and used throughout America in the nineteenth century.

Dish, Ralph Simpson, probably Burslem, Staffordshire, 1680–1720. Slipware. D. 18 1/4". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Pair of sauce boats, London, ca. 1760. Tin-glazed earthenware. L. 8 1/4". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Knife and fork, Staffordshire, ca. 1760. Salt-glazed stoneware. Knife: L. 8 1/8". Fork: L. 7 1/4". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of shell-edge treatments of dishes illustrated in fig. 18. (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dishes. Left: probably Liverpool, ca. 1800. Pearlware. L. 18 3/4". Right: Staffordshire or Liverpool, 1775–1810. Pearlware. L. 18 3/8". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chamber pot, Donyatt, North Devon, 1680–1700. Slipware. H. 6 3/4". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tureen, Staffordshire, ca. 1765. Creamware. H. 8 3/4". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

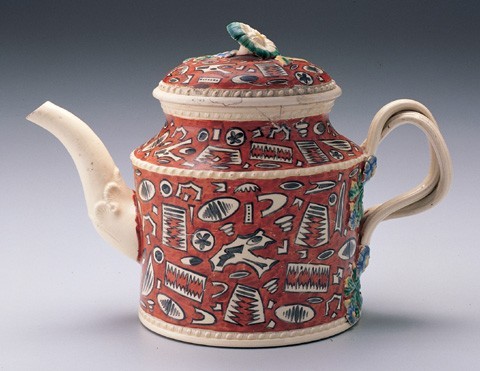

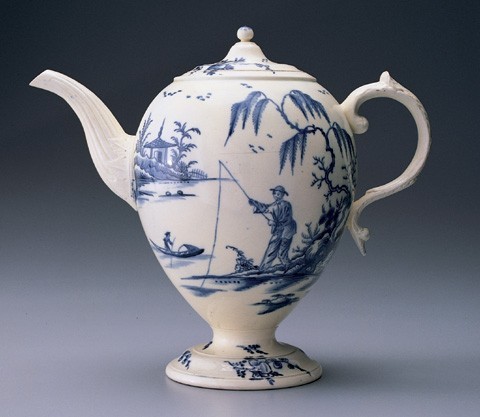

Teapot, probably Yorkshire or Staffordshire, ca. 1765. Creamware. H. 5 3/8". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Enameled in the so-called fossil pattern.

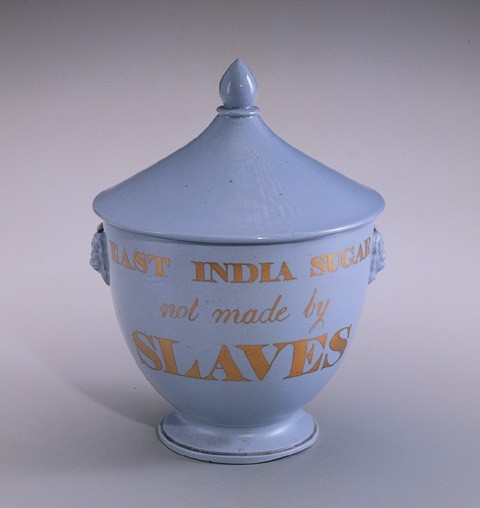

Sugar bowl and lid, Staffordshire or Sunderland, ca. 1820. Earthenware. H. 6". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Inscribed “EAST INDIA SUGAR NOT MADE BY SLAVES,” these antislavery slogans on ceramics were often commissioned for abolitionist societies.

Coffee or chocolate pot, probably Yorkshire or Staffordshire, 1775–1790. Creamware. H. 8 7/8". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tyg, Wrotham, Kent, 1649. Slipware. H. 5 7/8". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) We might imagine the meeting of human and ceramic lips from the evidence of myriad chips on vessel rims. Multiple handles here also enabled passing the vessel from person to person, mouth to mouth.

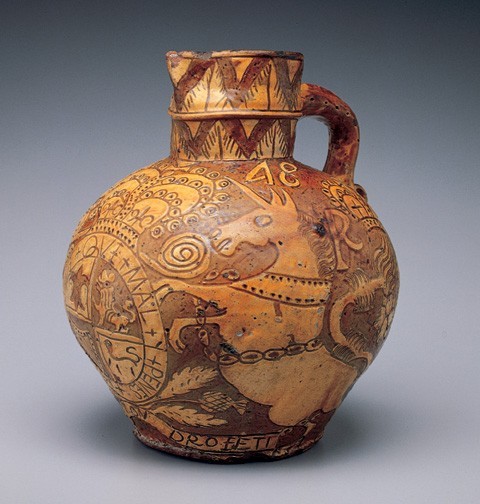

Harvest jug, Barnstaple or Bideford, North Devon, 1748. Slipware. H. 12 1/8". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

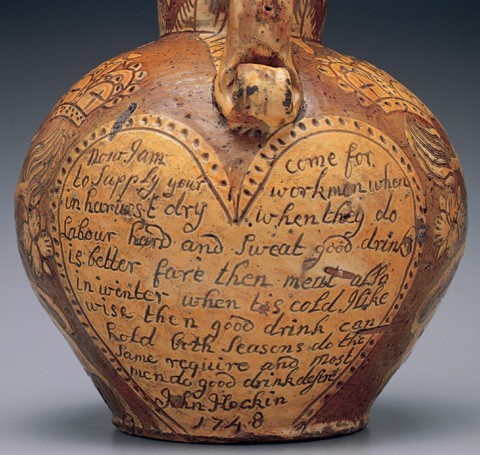

Detail of the jug illustrated in fig. 22. “Now I am come for to Supply your workmen when in harvest dry when they do Labour hard and Sweat good drink is better fare then meat also in winter when tis cold I like wise then good drink can hold both Seasons do the Same require and most men do good drink desire John Hockin 1748.” (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Hand-colored engraving, “The Advantages of Wearing Muslin Dresses!,” James Gilray. Published Feb. 15, 1802, by H. Humphrey, 27 St. James Street, London. (Private collection.)

Detail of the engraving illustrated in fig. 27.

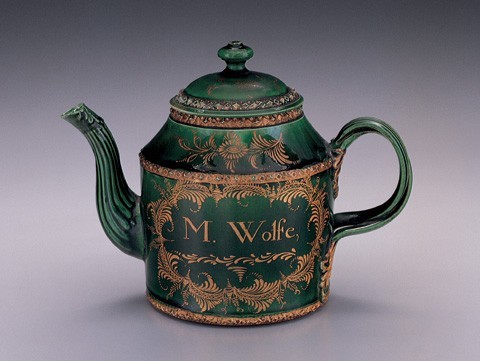

Teapot, probably Derbyshire, ca. 1770. Creamware. H. 6". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) An unusual green-glazed creamware teapot with the added embellishment of cold-gilding and the inscription “M. Wolfe”.

A Flood, Sir John Everett Millais, 1870. (Courtesy, Manchester City Art Galleries.)

The power of beauty in everyday things underlies a long and enchanting tale from the mid-nineteenth century. The story begins in a disheveled crockery shop that, reflecting the nature of its proprietors, is filled with cheap, “dusty cups and saucers, of the coarsest kind and ugliest shapes.”[1] In this dismal setting, two women meet by chance: one, a good-hearted seamstress whose teapot has just been broken; the other, the daughter of a pottery manufacturer, left penniless by her father’s untimely death. In the throess of poverty, the young maid has come to sell her most prized possession—a brilliant blue china teapot described as having the shape of a melon, with richly colored buds, leaves, and flowers, and tendrils of honeysuckle (fig. 1).

The good-hearted seamstress took the beautiful vessel home, which immediately improved the tea-table behavior of the girls employed in her sewing shop. The teapot’s former owner was able to overcome her financial distress and opened her own neighborhood crockery shop. Stocked with inexpensive but beautiful new wares, the little shop brought a whole new level of interest in art and refinement to the neighborhood’s working class. They came in droves to buy new dishes and figurines to adorn their simple homes. A happy ending for all! And why not? After all, the “vital impulse necessary to artistic love and artistic excellence may be given to the child by the figure on his dinner-plate, or the form of his drinking cup.” The artistry of these new wares continued to influence the local populace: “the little black classic figures upon the teapots have led to a taste for plaster casts; [such as] the Girl taking a thorn from her Foot, the dancing Hebe, the Child at Prayer, Eve at the Fountain.”[2]

For those in this story, the availability of new and better wares engendered aesthetic appreciation, better manners, and a more pleasant domestic environment. Scattered throughout their dwellings were “small efforts of refinement, humble as they are on chimney-piece, spare table, or buffet.” At the end of the tale, such pleasing homes could lead men and women away from the gin shops. In these everyday vessels, “a germ may be set...[to] elevate the moral being”[3](fig. 2).

“The New Crockery Shop” by Eliza Cook is one of many Victorian morality tales peopled with stock players—poor beauties, good-hearted strangers, and wealthy blackguards. The catalyst for moral elevation is an innocuous set of objects: available, affordable, and desirable ceramics. The result? Redemption by aesthetics into a better world. As the story’s narrator intoned, “art is invested with a sublime prerogative.”[4]

Behind every good story lies an essence of truth. Teapots of the mid-nineteenth century could, indeed, be coarse and brown or refined and iridescently colorful. Several generations of technological advances in the potting industry—plaster molds, transfer printing, refined clays—had produced an explosion of highly decorated wares reaching new levels of beauty. In reality, the story’s characters reflect the early modern world’s delight with thinner ceramic forms and more vibrant colors, resulting from centuries of “china mania.” The working people of Cooke’s story represent an entire social class “passionately fond of crockery.”[5] Part of their passion came from the novelty of the products: new, everyday wares that were more colorful, exciting, and elegant than ever before. And, as importantly, lower prices enabled more households to enjoy them. Nevertheless, their fondness for crockery also emanated from deeply rooted, often unconscious, and slow-changing cultural values embodied in the wares.

Some say ceramic dishes have powers. At one time or another, ceramic wares have been thought of as mythical, magical, practical, and sublime objects. After all, according to Judeo-Christian tradition, humanity itself was shaped in clay (fig. 3). The process of making a cooking pot, while no longer considered a divine act, is a transformation of what is natural to what is artificial. This act can be expressed as an opposition: nature (clay) versus culture (cooking pot). Another opposition is expressed in the function of the cooking pot. Cooking pots transform natural products (raw) to foodstuffs (cooked) (fig. 4). This most basic opposition is a direct way to analyze the role of ceramics, not only in our own society but also in other cultures of the world.

In nineteenth-century Silesia, people still believed there was a mountain from which cups and jugs sprang spontaneously, “like mushrooms from the soil.”[6] Since food is elemental to life—and its processing and sharing a basic cultural form—the pots and dishes in which it is prepared and served can have a deep, hidden significance. Multiple cultures even record tales of magical cooking pots that refill themselves with food when dearth threatens.

Pottery’s cultural significance is part of the realm of myth and magic. Ceramic vessels are practical containers for the sacred essence of life—food and water. Their use is nearly universal, crossing cultures, classes, and time. Ceramic vessels, because they are made from an easily malleable medium, can readily express the culturally prescribed notions of beauty. Ceramic objects are earth that, by the hand and eye of the potter, becomes art. The objects can be practical or ornamental, although all fit somewhere on a continuum of convenience and aesthetics. They can be beautiful in their inherent characteristics of form, glaze, texture, and decoration. And they can be sacred, as statues or vessels used in ritual ceremonies (fig. 5).

Thus, ceramics leap and soar through multiple categories of analysis. Just as some wares can be mysterious and elemental, others can be practical. The analysis of meanings may require an understanding of the complex interrelationships between commerce, science, and art. For example, when Josiah Wedgwood and Thomas Bentley purchased the Comte de Caylus’s seven-volume work Recueil d’Antiquitiés to study the latest antiquities uncovered from the classical world, they were connoisseurs of art. When Wedgwood or Bentley customized specific vessel drawings by sketching in an additional handle or foot, they were businessmen who understood what modern eighteenth-century amenities would appeal to the buying public (fig. 6). When they needed to devise new manufacturing methods and find new materials, Wedgwood, an industrial scientist, drew upon his considerable technological knowledge and relied upon continuous experimentation.[7]

The possibilities for the study of ceramics are dizzying. Ceramics have much to say about everyday life. As material culture, their creation, use, and interpretation can be expressed as tangible products of human behavior. Because of their range of functions and widespread use, many observers of human behavior rely upon pottery as a ready source of data. Pottery has a myriad of archaeological, historical, economic, artistic, and social stories to tell. The folklorist Henry Glassie avers that pottery is the most intense of the arts; that is, pottery packs more cultural information into the smallest amount of space.[8]

The challenge, then, is to find an orderly method for its study. The following brief analysis illustrates the methods I use to organize thoughts about a wide array of ceramics. The model of study I propose is simple. Just like fictional tales or paintings, ceramic vessels speak. Numerous issues and themes, from economics to behavioral conventions, link ceramics across place and time. By identifying these relationships we can begin to pull together a kind of order or matrix that organizes them.[9]

To understand the use of ceramic wares in a given place and time, we must look at the makers, the buyers, and the users (not often the same person in early modern Western society). Issues of technology, time, space, function, and human behavior are only a few of the variables that are part of the matrix of ceramics study. In considering the making of an object, variables include the potter’s vision, skills, and tools. A given design is enabled or constrained through multiple factors ranging from the availability of quality clay to the ease of transporting finished products to the consumer. Once the object is made for the market, it steps into an arena of consumer choice and use. The area of choice is the interim space between economic systems and the human passion for particular things. Finally, when we speak about use, we ask questions about variations of the relationship between object utility and human behavior.

Ceramics are dense carriers of meaning. Multiple questions can be asked of any one object but not every object answers every question best. The most useful questions often come from the object itself and may take the analyst in unexpected directions (fig. 7). As an example, the summary of questions and answers that is presented in figure 8 outlines one study method for approaching a ceramic artifact.

Along with those summary questions and answers, the larger sketch that follows is a wide-ranging account of such objects in seventeenth- through nineteenth-century Anglo-America. Together, they ultimately move the scholar from looking at objects to looking at a culture.

To begin: studying ceramics in America—a carefully chosen phrase—denotes complexity. Americans nearly always had choices among wares imported from (or through) Europe, as well as from those made locally. Before the twentieth century, American men and women were likely to eat food stored in American-made ceramic wares, but served on wares made in England. Beverages were often drunk out of hollow vessels from Germany (alcohol) or China (tea). Thus, two loose categories of study concerning the maker emerge: (1) wares made in America and (2) wares made abroad and imported to America.

The people indigenous to the Americas made pottery long before European occupation and supplied “Indian pots” to European settlements long after their arrival. African slaves brought ceramic technology with them and made low-fired earthenware often shaped and decorated to reflect their own cultural preferences and iconography. European and, later, American potters supplied earthenware and, eventually, utilitarian stoneware to a rapidly expanding colonial population. The creolization of people and cultures from Europe, Africa, and America can be traced in our ceramic heritage, and is, perhaps, one of the most exciting new ways to think about both ceramics and America.[10]

A number of significant trends occurred in the exportation of ceramic wares to America. Ceramic vessels were an important commodity that flowed from the places that expertly made them (Holland, China, Germany, England) to the places that wanted and needed them. Ironically, the English people sometimes ate and drank from the wares of their greatest political rivals. Most wares found in the American colonies after 1660 were controlled by the English merchants as specified in the Navigation and Trade Acts. With the development of the Staffordshire pottery industry in the late seventeenth century, virtually all imported wares were of English origin.

But what happened after colonists fought a revolution, ultimately to break the shackles of a foreign power? Politics changed, but pottery did not. Plates and dishes poured across the Atlantic for a century after political independence. The flood of images that celebrated the apotheosis of George Washington to mythic greatness was printed on English wares (fig. 9). The proud eagle that became a motif and sign of American nationalism was painted on English wares (see fig. 7). The forms of decoration changed, but the source of pottery did not.

Nevertheless, even if the Americans did not make their own plates, they did have a considerable say in what those wares looked like. The colonies were marginal to the profits of Staffordshire in 1770, and shipment of various new styles often lagged years behind their initial introduction. By 1824, however, a historic event like the landing of the Revolutionary War hero Marie-Joseph Lafayette in New York could be recorded as a print, transferred to earthenware, and be en route to the United States market in only five months’ time (fig. 10).[11]

Throughout the nineteenth century, many Americans considered English wares superior to any others available to the American market. American merchants continued to advertise their stock of the latest and best imports. Jonathan Ludlow of Charleston, for one, trumpeted that he stocked fashionable imported crockery by printing the claim on the wares themselves (figs. 11, 12). European and English pottery factories have continued their reputation for fine quality wares today. By the late nineteenth century, however, the growth of American firms succeeded in filling multiple market niches for ceramics.

In sum, to organize the study of the making of ceramics used in America, the researcher might first see the task as both local and global. In my own work, I generally think of three concepts that express degrees of variability. A person thinking visually might imagine a series of axes along which any vessel could be placed. The first line represents technology, ranging from simple, low-fired earthenware to complex, high-fired porcelain. The second line, representing time, attempts to assess the extraordinary cultural changes reflected in the history of ceramics. And the third line delineates space, or place. A ceramic can be made and used virtually in situ. More often it was made locally or imported from faraway cultures and regions, like Europe or East Asia.

Thus, issues about the making of ceramics may begin, literally, with the ground underfoot, but can quickly lead to questions about important institutional changes, massive economic forces of trade and industrialization, and elements of power and competition. Our matrix is partially built.

A researcher who goes on to study how ceramics are used adds more constructs, more lines to the matrix. He or she can address the intimate details of daily life or the public performances of parlor. Arcing through these stories of ceramic use is the extraordinary variety of function and allied human behavior. Nearly all humans use ceramics. But how they are used is usually quite culturally specific and often ritualized. Ritual use can mean the pouring of holy waters in a religious rite. However, in a more everyday sense—as learned and repeated behavior—ritual is manifested in building practices, foodways, and intimate social activities. If we wash our face in the sink, not in the toilet, we are displaying our sensibilities about human waste and care for the body. We are free to choose the toilet for our washing, but few, if any, do.

To begin the story of ceramic use, nothing is more integrally linked with ceramics than food and water. When storing, preparing, and serving food, people act in prescribed ways and with a myriad of objects that show how behavior is patterned and transmitted within a given culture. Before refrigeration, foodstuffs were often pickled in acidic media to stave off hunger through the lean days of winter. Glazed and fired clay vessels, such as stoneware, were the preferred type for protecting perishables. Hence, food storage was probably the most common use of clay vessels in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century homes (fig. 13). Preparing food also necessitated bowls, dishes, cooking pots, and other ceramic implements. These vessels for food storage and preparation were common and their forms and decorations were relatively constrained. This characteristic expressed both their utilitarian function and their place in domestic space; that is, usually out of public view.

Objects used in food serving, on the other hand, were more sensitive to cultural variability. The changes in tableware during the short history of Western people in America are part of a dramatic storyline. Significant transformations took place over time (and continue to do so). For example, a single large serving dish was an object appropriate for the tables of even well-to-do households in 1660. And like the palette on the large charger made by Ralph Simpson, many of these household vessels were largely the colors of earth, forest, or mine (fig. 14).

A century later, a well-set table of the upper class would include multiple individual plates, hollow serving vessels for sauces, dishes for culinary complements to meat, and an array of objects to serve extra courses. All were available in a broad variety of forms with a variety of decorations (fig. 15). The changes in the forms of everyday wares that followed reflected a continuing formalization of behavior. Dining was a theatrical performance of learned manners. Dishes became props. Those who dined used implements to separate their bodies from their food. Forks and knives became surrogate fingers (fig. 16).

Styles of decoration also ebbed and flowed, but the sum effect of technological breakthroughs and ever-changing desires was that mid-eighteenth-century consumers had more choices than ever before. Understanding those choices demonstrates how complicated the world of pottery had become. Case in point: the use of large platters continued into the early 1800s as the honorific stage for an expensive cut of meat. A common form of late-eighteenth-century and early-nineteenth-century decoration was a painted, feathered rim resembling the edge of a shell (hence, the name “shell edge”) (fig. 17). To produce this decoration, a manufacturer had to choose the levels of skill, time, and materials involved and, consequently, the cost and potential profit. Thus, one shell-edged platter might display gilt; another, blue paint. The more expensive gilt-edged version might be decorated with classical motifs of the latest fashion; the less expensive, blue-painted one, with a time-honored Asian design such as the Chinese house pattern (fig. 18).

To elaborate on the stylistic variables popular with Anglo-American consumers by the end of the eighteenth century, Josiah Wedgwood and a host of potters responded to, and helped shape, the public’s excitement for newly discovered classical antiquities by producing modern copies and interpretations. This trend arose in the midst of a century-long passion for Asian design. But one did not replace the other. Potters produced classical vases and pots for the elite, who followed the latest fashion as a means of communicating their wealth and social status. The “middling”- and lower-class customers still enjoyed Western versions of Asian designs, which were increasingly affordable as prices declined. Thus, any search for a progression of taste and style is filled with crosscurrents inherent in any complex social system.

By the late eighteenth century and beyond, upper- and middle-class families did share the belief that a matching set of dishes was a good first step toward proper dining decorum. Today, informality of daily life increasingly challenges this structured use of tableware. Specialized spaces for dining have diminished and family mealtimes are under challenge. Equally significant, the taboos that arose during the Renaissance against touching food with the hands in polite society have eroded.[12]

This twentieth-century reversal partially came about from the most innocuous of sources—the sandwich. With the sandwich, we can now use bread to avoid touching the meat. Cutlery is unnecessary. And with paper food wrappers, even the plate is no longer needed. This type of on-the-go, throw-away mealtime has become the norm. We retain vestiges of social relations that were new to the eighteenth century when we gather around the table at Thanksgiving. Then, once more, the ceremonial stage gains prominence with clean linens, gleaming tableware, and the turkey platter, the table’s central podium.

The history of ceramics and food consumption are inextricably intertwined. Ceramics, however, fulfilled many less obvious needs. Standards of hygiene, for example, like ideals about cuisine, grew increasingly structured as the eighteenth century progressed. Just as keeping one’s body clean became more routine, vessels for washing and shaving became more necessary. The corollary to a purer body would be a more adorned body, necessitating the use of cache or small ointment pots to store color and powder. All of these taboos about nature and natural appearances (unwelcome dirt, hair, or skin condition) expanded to include ideas about the removal of bodily waste. People welcomed an increasing number of chamber pots (fig. 19). The particular shapes and sizes of chamber pots were significant, with preference presumably based on utility: number and sex of users, frequency of emptying (and by whom), and even stability if accidentally kicked in a dark bedroom. As the vessels became more common, they also became more varied. One store inventory in 1800 listed five different sizes of chamber pots.[13]

Even while the deeply symbolic movement from nature to culture was ongoing, an admiration of nature and its classification led to a fashion for disguising and replicating nature in artificial forms. A gentleman who gardened grew masterful fruit. A gentleman who dined ate from masterful ceramic fruit (fig. 20). A gentleman interested in archaeology might drink from a teapot replicating a Greek vessel or one whose body mimicked geological processes (fig. 21). Both form and decoration could replicate nature.

Nonetheless, ceramics did not merely illustrate the larger world. Ceramics taught people. Popular forms and decorations allowed the viewer to trace the vines or the ribs of the shell. After the advent of transfer printing, one who gazed at a ceramic vessel might more easily read poetry, or be urged to moral certitude by the aphorisms of Poor Richard, or the sloganeering of the abolition trade (fig. 22). Most significantly, ceramics allowed imaginary travel to unknown places. The Western world’s affection for the exotic products of Asia led to massive production for millions of curious consumers. Not realizing (or perhaps not caring) that the images of China were fantastical, Europeans could travel to the Far East through the tracings on their teacups. They could gaze at “courtly Mandarins” or delicate Chinese women “stepping into a little fairy boat, moored on this side of a calm garden river.”[14] Indeed, Robert Southey believed that “the plates and tea-saucers have made us better acquainted with the Chinese than we are any distant people” (fig. 23).[15]

So far we have imagined the physical interaction between ceramics and humans as cool or warm clay meeting hands and fingers or, if one is balancing a heavy burden, perhaps encountering even a hip, shoulder, or waist. We have allowed eyes to read and brain to enjoy rich color and cool hue. But a significant interaction between human and ceramic remains. Both cups and people have lips and the shared name may be no accident. Often the two, mouth and cup, would meet. Here again, the range of activities, formal and informal, everyday and special, produced an astonishing array of forms.

Vessels for consuming alcohol, whether used medicinally or simply to help forget the daily grind, were common in both households and taverns. Even more than ceramic wares used for dining, the extraordinary shapes of drinking vessels demonstrate ritual use. Many of the vessel forms for drinking alcohol embodied the communal aspects of the drinking. Seventeenth-century multihandled forms, such as tygs, give ample evidence of their use: a centrally placed drinking vessel that could be reached from multiple sides or passed from person to person (fig. 24). Punch bowls, too, went hand to mouth around a group. To our twentieth-century eyes, some of the most whimsical vessels of the past are the puzzle jugs, whose purpose was as much to promote merriment and camaraderie as to serve alcohol. In the same way, the form of the harvest jug tells much about the action of farmers and field workers, often neighbors, who joined forces to bring in the harvest. Passed hand to hand, these large storage vessels quenched the thirst of a hard day’s labor. What the ditties and poems celebrated in writing, the form often did in clay (figs. 25, 26). Moreover, the flood of individual-size stoneware mugs of the eighteenth century suggests that, like dining, drinking had become a more independent pursuit.

The rituals of drinking have changed markedly in the history of America. Centuries-old puzzle jugs seem whimsical, but we also wonder at today’s martini hour and all its associated accoutrements for measuring, shaking, and serving. Gathering around a punch bowl has been mostly reduced to the ceremonial occasions of weddings and holidays (as is usually the case with a dying custom) or to those nonalcoholic public events of church and state. Mugs are for coffee, not beer.

Even more arcane and incomprehensible to some of us today is the elaborate social ceremony surrounding tea time of one or more centuries ago. But remember, it was a teapot that led to redemption in “The New Crockery Shop.” It was the improved tea-table behavior of the shop girls that was evidence of moral improvement. It was the pleasant home and warmth of the tea table that led the poor away from the gin shops. Poetic license of storytelling aside, public alcohol consumption did decline in the nineteenth century, coincident with the rise of private tea drinking. There, two activities were also dialectically opposed in their gender connotations. When men drank alcohol at home in a formal setting, women left the room. When men drank tea, women controlled the room.

When people took tea, they were loosely or tightly grouped around a set of objects, quite specialized to the task of sipping tea. A table, whose form was new and specifically functional to serving tea, was often center stage. Upon it was a host of paraphernalia necessary for precise performance of a ritualized event. A set of rules, from proper pouring technique to polite conversation, grounded this elaborate performance. Of course, as shown in figures 27 and 28, performances did not always follow the script. And at absolute center stage was the teapot. While silver and other lesser metals were used, porcelain and earthenware teapots were often thought to be the most beautiful and produce the best-tasting tea. The unknown “M. Wolfe”’s stunning green glaze and gilt teapot was beautiful, but a name was added to assure prominence (fig. 29). That extraordinary centrality of the teapot in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century life, first for the well-to-do, then for the working class, is comparable to the 1960s television set that clustered family and friends together around one object, perhaps with a new-fangled ceramic snack set. (Today, the family members may be scattered though the house watching television and drinking coffee from personalized mugs.)

In this way, teapots became the daily prop that was handled by the star of the household and admired by all. People closely followed their changing forms and decorations. They were as much a part of evolving fashion as female clothing. For others, such as the good-hearted seamstress of “The New Crockery Shop,” the teapot’s value came from years of daily sharing—the pot became a physical symbol of passing time and pleasant company. Hence, her gasp as the pot crashed to the floor was for more than shattered crockery.

This essay opened with a story of a beautiful blue teapot. The tale worked because it expressed for its author and its audience what they thought, imagined, or wished to be real. Paintings, too, record a kind of truth and fiction. For example, in 1864, a flood inundated Sheffield, England. A contemporary poem recorded that a cradle, with child and kitten still asleep inside, had been swept out of a cottage by the watery deluge. Sir John Millais recorded the scene in an 1870 painting, simply titled A Flood (fig. 30). In Millais’s painting, the baby awakens in surprise and delight at the scene before her and the kitten mews in half-drenched misery. No less a tale of Victorian pathos than “The New Crockery Shop,” the sentimental scene suggests both the horror and the miracles of such a natural disaster. The household furniture, the infant, and the pet—all combine to create a domestic scene. A ceramic jug, floating in the bottom corner of the picture, is only half submerged. It floats almost magically along with child and cat—the survival of each, a symbol of hope.

The jug was not in the original painting. Fifteen years after its execution, Millais “re-touched the picture extensively with the view to re-storing to it some of the sparkle of which Time had robbed it.”[16] The jug was added to the space on the canvas that had formerly been occupied by a pig. Replacing the pig with the simple mochaware water jug was the perfect imaginary and artistic touch. The jug was a simple, practical vessel for carrying water, drinking, bathing, and for household chores too many to count. Finally, like many utilitarian objects, it was hardly plain. The yellow ceramic body with hints of white and blue bobbing in the murky browns of the painting was sublime. The vessel was magical, mythical, practical, and sublime. The artist John Millais and the writer Eliza Cook both knew vessels carried more than water or tea. They could be used every day, but they could carry deep meaning.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many people helped with specific tasks in creating this work. These include Eleanor Gadsden, Nancy Sazama, Cate Cooney, Amy Ortiz Holmes, Jacob Esselstrom, Ryan Grover, Nancy Marshall, Frank Horlbeck, Anna Andrzejewski, Patricia Samford, Jon Prown, George Miller, and Rob Hunter. I am also grateful to Carl and Katherine Martin who had the uncanny ability to know whether to leave me alone or distract me away. All are due my thanks.

“The New Crockery Shop,” Eliza Cook’s Journal, vol. 1 (London: John Owen Clarke, 1849), p. 21. History of Women (Woodbridge, Conn.: Research Publication Series), microfilm, reels 52–53.

Eliza Cook’s Journal, vol. 1, p. 36.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid., p. 21.

Charles Wyllis Elliott, “Unglazed Pottery,” Art Journal, 2nd series, vol. 3 (New York: D. Appleton and Comp., 1877), p. 117.

Head Cantharus, vol. 1, pl. fifty-seven. Anne Claude Phillippe Caylus, comte de, Recueil d’Antiquitiés egyptiennes, etrusques, grecques et romaines, Nouvelle edition (Paris: chez Desaint et Saillant, 1761). The Chipstone Foundation has recently acquired the seven-volume set owned by Josiah Wedgwood and research is beginning into the series of annotated drawings and marks.

Henry Glassie, Material Culture (Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press, 1999), p. 222.

An earlier version of this kind of method can be seen in Ann Smart Martin, “Makers, Buyers, and Users: Consumerism as a Material Culture Framework,” Winterthur Portfolio 28, no. 2/3 (Autumn 1993): 141–157.

For Africans-Americans, see Leland Ferguson, Uncommon Ground: Archaeology and Early African America, 1650–1800 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1992). For an argument supporting the continued role of indigenous Americans, see L. Daniel Mouer, Mary Ellen N. Hodges, Stephen R. Potter, Susan L. Henry Renaud, Ivor Noël Hume, Dennis J. Pogue, Martha W. McCartney, and Thomas E. Davidson, “Colonoware Pottery, Chesapeake Pipes, and ‘Uncritical Assumptions,’” in Theresa A. Singleton, “I, Too, an America”: Archaeological Studies of African-American Life (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999), pp. 83–115 . Ferguson, Uncommon Ground.

George L. Miller, Ann Smart Martin, and Nancy S. Dickinson, “Changing Consumption Patterns: English Ceramics and the American Market, a Case Study,” in Everyday Life in the Early Republic, 1789–1820 (New York: W. W. Norton for the Winterthur Museum, 1994).

Charles L. Venable, Ellen P. Denker, Katherine C. Grier, Stephen G. Harrison, China and Glass in America 1880–1980: From Tabletop to TV Tray (New York: Harry N. Abrams for Dallas Museum of Art, 2000).

Edward Dramgoole Store Inventory, October 1, 1800, Brunswick County, Virginia. Dramgoole Family Papers, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

Charles Lamb (1775–1834) “Old China,” in A Book of English Essays, edited by W. E. Williams (New York: Penguin English Library, 1980), pp. 92–100.

Robert Southey, Letters from England, edited by Jack Simmons (London: 1807; reprint, London: The Cresset Press, 1961), pp. 191–192.

Robert Southey, Letters from England, edited by Jack Simmons (London: 1807; reprint, London: The Cresset Press, 1961), pp. 191–192.

16. John Guille Millais, The Life and Letters of Sir John Everett Millais, vol. 2 (New York: Frederick A. Stokes Co., 1899), pp. 18–19. M. H. Spielmann, Millais and His Works (Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1898), pp. 115–116.