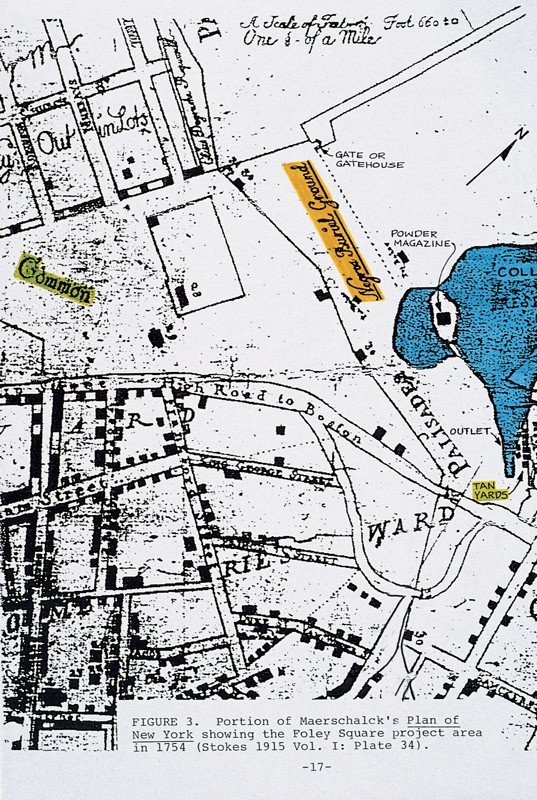

Detail of F. Maerschalck’s Plan of New York from an Actual Survey, Anno Domini M, DCC, LV (depicted 1754; issued 1755) showing the Foley Square project area. (Photo, courtesy John Milner Associates.) The original is in the collection of the New-York Historical Society; it is reproduced in I. N. Phelps Stokes, The Iconography of Manhattan Island, 1498–1909, 6 vols. (1915–1928; Union, N.J.: Lawbook Exchange, 1998), vol. 1, The Period of Discovery (1524–1609), pl. 34.

Jar, Clarkson Crolius, New York, New York, ca. 1800–1814. Stoneware. H. 18". Mark: “C. CROLIUS / MANUFACTURER / MANHATTAN-WELLS / NEW-YORK” (New York State Museum; photo, Rob Tucher.) This jar was excavated from an early-nineteenth-century context at the Barclays Bank site. The maker’s mark is stamped on one side, and an incised floral motif is on the other. Both are filled in with blue.

Jar, Clarkson Crolius, 1800–1814. Stoneware, cobalt oxide. H. 11", D. 7 1/2", Mark: stamped on shoulder, “C. CROLIUS / MANHATTAN-WELLS / NEW-YORK” (Courtesy, New-York Historical Society, 1937.808.) Two variations of the “floral moosehead” motif, joined by a blue band, surround this Crolius jug.

Contemporary advertisement for Corzelius Pottery, Hohr-Grenzhausen, Germany, 2003. (Photo, Meta Janowitz.)

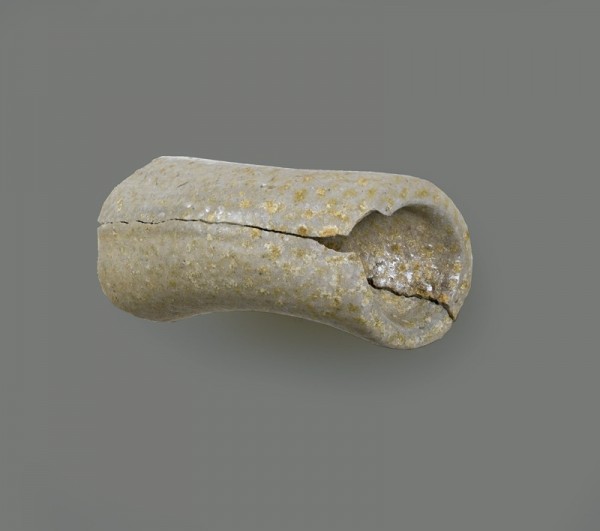

Jug fragment, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, Rob Tucher.)

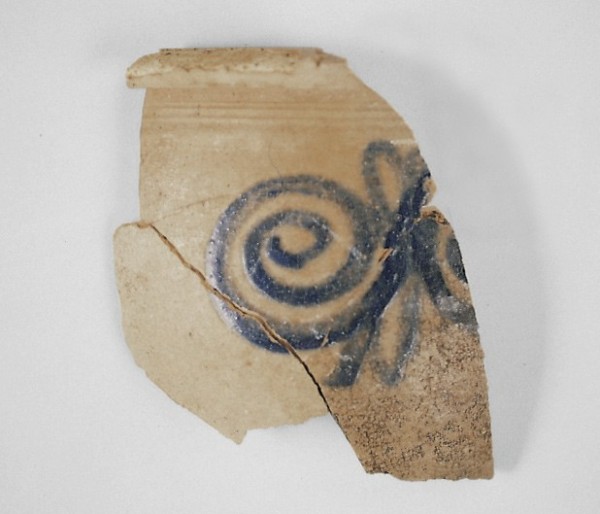

Jar fragment with spiral motif, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, John Milner Associates.) This sherd was destroyed when the World Trade Center collapsed on September 11, 2001.

Jar fragments, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, John Abbott.) Note the spiral motif on this underfired small-mouthed jar.

Rounded porringers, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, Joseph Balicki.) The vessel at right was covered with a brown slip. These were destroyed when the World Trade Center collapsed on September 11, 2001.

Slant-sided porringer, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, Joseph Balicki.) This porringer was destroyed when the World Trade Center collapsed on September 11, 2001.

Tankard fragments, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, Rob Tucher.)

Tankard fragments, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, John Abbott.) These underfired sherds have an incised and cobalt-filled motif.

Dish or shallow bowl fragments, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These sherds show brushed cobalt decoration over a brown slip.

Plate rim fragment with painted motif, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Molded teapot spout, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jar rim fragment, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, John Abbott.) This represents the most common type of rim profile for jars.

Jar rim fragments, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, John Abbott.) The assemblage here displays a variety of profiles.

Chamber pot rim fragment, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, John Abbott.) This sherd shows blue decoration around the handle attachment as well as on at least one side.

Small jug or round mug sherds, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, John Abbott.) The rat-tail handle attachments shown here are outlined in blue.

Handle fragments, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, John Abbott.) A variety of handle shapes is shown.

Ointment pot or test piece, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. Mark: incised on base, “IS” or “SI” (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, Rob Tucher.)

Sherds, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, Rob Tucher.) Almost all of the fragments in this group were decorated with variants of the spiral motif. They were destroyed when the World Trade Center collapsed on September 11, 2001.

Jug fragment, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, John Milner Associates.) These fragments, with a painted spiral motif and handle base encircled with a blue band, were destroyed when the World Trade Center collapsed on September 11, 2001.

Jar fragment with “spiral butterfly” motif, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, John Milner Associates.) This sherd was destroyed when the World Trade Center collapsed on September 11, 2001.

Sherds with cobalt spiral and notch decoration, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, John Abbott.)

Jug fragment, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, John Milner Associates.) From this remnant we can see that the top half of the jug was covered in brown slip. The fragment was destroyed when the World Trade Center collapsed on September 11, 2001.

Jug fragment, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The fragment shown here displays brown slip and an unidentified incised motif.

Plate fragments, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This unusual plate is decorated with a brown slip and an incised motif.

Sherds, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, Rob Tucher.) The sherds are decorated with incised and filled-in motifs.

Tankard fragment, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, John Abbott.) This piece shows an incised but uncolored motif and cordons filled in with blue.

Sherds, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, John Abbott.)

Sherd, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, John Abbott.)

Small jar fragment, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, Rob Tucher.) The incised star motif is filled in with blue and a manganese slip. The fragment was destroyed when the World Trade Center collapsed on September 11, 2001.

Sherds, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photos: Rob Tucher, left; John Abbott, right.) These sherds are stamped and incised, and the motif is filled in with blue. Note the double stamping of the flower, which is very similar to the one used on the Barclays Bank jar illustrated in fig. 2.

Jug or mug fragment, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, John Abbott.) This sherd shows part of a sprigged GR medallion.

Sherd, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, Rob Tucher.) Based on comparisons to intact examples, the remaining sprigged motif on this sherd, which was destroyed on September 11, 2001, was part of a GR medallion.

Sherds with rouletted motifs, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, John Abbott.)

Porringer fragments with diagonal rouletted motifs, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, John Abbott.)

Jar fragment with rouletted motif, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, John Abbott.)

Jug fragments with rouletted motifs, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, John Abbott.)

Chamber pot fragments with rouletted motifs, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, John Abbott.)

Jug fragments, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, John Milner Associates.) These partially mended jug sherds have wide bands of rouletted motifs. All were destroyed when the World Trade Center collapsed on September 11, 2001.

Rim fragment with brown line, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, John Abbott.)

Rim and handle fragments with blue dots, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, John Abbott.)

Sherds with interior brown slips, Crolius/Remmey families, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1720–1765. Stoneware. (African Burial Ground Collection; photo, John Abbott.) Note the variety of hues.

The events of September 11, 2001, affected the lives of virtually all Americans. Buried amid the overwhelming losses of the day, the destruction of two archaeological collections was a matter of minor concern, except perhaps to those archaeologists working with the collections. None of the members of the archaeological staff was hurt in the destruction of the World Trade Center, but almost all of the artifacts from the Five Points site and more than half of those from the African Burial Ground were lost when a tower support column fell through the basement office/storage area of the Customs House at 6 World Trade Center, where the collections were housed. The analysis of the Five Points site had been completed and a comprehensive, six-volume report prepared.[1] The analysis of the artifacts from the African Burial Ground, however, was only partially done.

The Five Points and African Burial Ground sites were excavated in 1991 and 1992 for the General Services Administration (GSA), first by Historic Conservation and Interpretation (HCI) of Newton, New Jersey, and then by John Milner Associates (JMA) of West Chester, Pennsylvania. The African Burial Ground, identified as the “Negroes Burial Ground” on early maps (fig. 1), was the resting place of an unknown number of enslaved people (perhaps as many as twenty thousand) buried there throughout the eighteenth century. More than four hundred bodies were exhumed before excavations were halted. After negotiations between the GSA, Congress, and the descendant community, excavations were stopped, and the area eventually was designated a New York City Historic District and a National Historic Landmark. The analysis of the excavated human remains and artifacts from the African Burial Ground was divided between JMA and Howard University in Washington, D.C.: the human remains and the artifacts associated with them, along with those from contexts identified as burial shafts, were analyzed by Howard University staff; those from the nonburial portions of the site were analyzed by jma.[2] Before September 11, artifacts from the nonburial portions of the site had been analyzed at a basic level and the data entered into a computer coding system, but the artifacts from the grave shafts had not yet been fully inventoried. Most of the artifacts from the nonburial-related contexts—the majority of the collection—were destroyed; in contrast, most of the grave-shaft artifacts were retrieved during cleanup of the World Trade Center site. The human remains and their associated artifacts were at Howard University and thus were spared; in October 2003 they were reburied at the location of the original African Burial Ground. The artifacts recovered from the World Trade Center were not available to archaeologists until early in 2003, when analysis recommenced. Archaeologists were left with part of the artifact collection and a computer record of the lost artifacts. While some of the sherds had been documented with slides, the entire collection was not photographed.

My involvement with the African Burial Ground project was as a consultant to both JMA and Howard University for the analysis of the stoneware ceramics recovered during that excavation. New York City stonewares are frequently recovered from archaeological sites throughout the metropolitan area; the large jar illustrated in figure 2 was found at the Barclays Bank site, on the corner of Wall and Pearl Streets in Manhattan. Curiosity about this vessel led to research about the Crolius potters.[3] The Crolius pottery was very close to the site of the African Burial Ground, and I badgered the late Ed Rutsch of HCI until he included me in the project. Daniel G. Roberts, Charles Cheek, and Allan H. Steenhusen of JMA and Jean Howson, Warren Perry, and Leonard Bianchi of Howard University were kind enough to continue the association.

The primary objective of the African Burial Ground excavations was, as is right and proper, to retrieve human remains and their associated artifacts in order to gather information about the enslaved population of New York City.[4] In the course of these excavations, however, more than fifty-six thousand sherds of stoneware kiln furniture and kiln wasters were recovered. Old maps of the area (fig. 1) showed potteries in an area sometimes referred to as “Pot Baker’s Hill,” and the excavators were not surprised to find kiln debris. Other craftsmen also left remains at the site: cattle foot bones and redware kiln furniture and kiln wasters were among the artifacts recovered. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, this area, which was on the outskirts of the city, was a suitable home for crafts with noxious by-products or the need for a great deal of space, such as tanneries, ropewalks, and potteries.

The land was originally one of the lower-lying areas of downtown Manhattan. When the area was developed in the early nineteenth century, it was filled to bring it up to the level of the surrounding streets, which accounts for the preservation of both the African Burial Ground and the stoneware sherds. The fill sealed and preserved the artifacts and features, a fact not known until excavations started, which caused a great deal of trouble for the gsa. As a result, in addition to needing extra monies for excavation, GSA had to contend with all of the difficult legal, ethical, and moral issues that surround the excavation of human remains.

Stoneware kiln furniture and wasters were found in two types of deposits at the site—the grave shafts of many burials and scattered over the site as a whole. The potteries were adjacent to the African Burial Ground, and potters dumped debris on the land used for burials. Some of the waster sherds and kiln furniture then became part of the soils used to fill in grave shafts. Unfortunately, in the sherds scattered throughout the site, excavators did not find any features that could be unambiguously associated with the potteries, although two shallow pit features (Features 139 and 144) contained concentrations of sherds. More than 22,000 vessel sherds, more than 19,000 pieces of kiln furniture, and nearly 15,000 fragments of miscellaneous kiln debris were recovered from all areas of the site.

The potters operating in the vicinity of the African Burial Ground, members of the interrelated Crolius and Remmey families, are New York City’s best-known artisan potters. The principal reason for their celebrity is their decorated and marked early-nineteenth-century wares, such as the Barclays Bank jar (fig. 2). Marked pieces and vessels attributed to Crolius or Remmey potters based on their incised and filled-in decorations are in many museums and private collections.[5] One motif in particular—some of us have called it a “floral moosehead”—is characteristic of Crolius-Remmey as well as of some of the potters trained by them.[6] Figure 3 shows a variation of this motif on a vessel in the collection of the New-York Historical Society.

Post-1800 Crolius and Remmey products are relatively easy to identify due to their distinctive decorations and maker’s marks. Both families’ kilns were taken over by members of the third generation in New York around the turn of the nineteenth century; those men were part of a new breed of craftsmen who marked their products as a marketing practice. Their marks were made with stamps consisting of one to three lines of print used together or separately. It is not known what percentage of the wares made by Crolius and Remmey after 1800 had maker’s marks, but utilitarian wares, not just special pieces, were stamped (the majority of marked vessels in existing collections are jars and jugs).

Surviving late-eighteenth-century vessels attributed to Crolius and Remmey potters usually have ornate decoration, with incised and/or stamped motifs filled in with cobalt blue, and any maker or decorator marks are painted freehand. The presence of such elaborate decorations and signatures showed the skill of the potter and probably indicates these were presentation pieces, made as gifts for an individual or group. For example, a heart-shaped inkstand inscribed on the bottom “New York / July 12th, 1773 / William Crolius / Tyler” was probably made as a gift or on commission.[7] Vessels such as these are much more likely to be preserved than the common, sparsely decorated vessels used daily for food storage and other uses.

Historical Background

Crolius and Remmey potters were working in New York City, however, well before the late eighteenth century. The first Crolius potter in the city (Johann Willem) and the first Remmey (Johannes) married into the family of an older stoneware potter, Georg Corsilius, who emigrated from the town of Nordhofen in the Westerwald region of Germany sometime between 1718 and 1724, when his daughter Veronica married Johann Willem (later simply William) Crolius.[8]

The name Corsilius (also Corcilius, Corselius, Cortselius, Cortzelius, and Kortzilius) continues to be associated with stoneware in the potting districts of the Rhineland (Das Kannenbäckerland, or the “Potbakers Land”), as it was during the nineteenth century (fig. 4).[9] “Crolius” is not found as a family name there, but it is probably a contraction of Corsilius.[10] The family name Remmey (also Remmy, Remy, and Remmi) was widely known during the early eighteenth century in the “Evangelical pottery areas.”[11] According to an exhibition panel in the Töpferei Museum in Raeren, the “Remy” family came to the Westerwald region from Alsace in the late sixteenth century. Along with the family of Knütgen from Siegburg, they were instrumental in establishing stoneware production in the Pot Bakers Land.[12] Georg Corsilius, Johann Willem Crolius, and Johannes Remmey were trained in the Pot Bakers Land in a centuries-old tradition that placed the production of stonewares in a family and guild setting. David Gaimster’s recent study of German stonewares provides a synopsis of the Kannenbäckerland craft background of the New York City potters.[13] Potters in the Rhineland were full-time craftsmen who worked within an apprentice-workman-master system controlled, after the seventeenth century, by formal guilds. Guilds were less institutionalized before the 1600s, but their authority to establish standards and regulate prices was still recognized. Under the guild system, production was “organized on a family-unit basis, with the main production centres comprising a number of competing families, each made up of several master-potters with their own kilns.”[14]

Corsilius, Crolius, and Remmey are examples of mature craftsmen who moved to America in the early eighteenth century because of the opportunities offered to practice their trades. As Carl Bridenbaugh stated, “To few people did America beckon more invitingly than the trained artisan.”[15] By 1728, when he became a freeman in New York City, Johann Willem Crolius was going by the name William Crolius; Johannes Remmey became John.[16]

We do not know how and why Georg Corsilius decided to come to America, but it is probable that he, or those who induced him to emigrate, was aware of the existence of stoneware clays in the New York–New Jersey area. Widespread deposits of stoneware and earthenware clays are located in a band across New Jersey from the Delaware River to Raritan Bay and in outcrops on Staten Island and Long Island. The Morgan family controlled much of the clay in New Jersey: they first bought land there in 1710, but the first documented mining and selling of their clay did not occur until 1764, although probably there were unrecorded sales before then.[17] The clay on the Morgan property was of high quality and accessible from the surface. The Morgans became suppliers of clay to potters throughout the Northeast and Midwest in the nineteenth century, but we do not know whether the Corsilius-Crolius-Remmey potters bought from them or from another source, or whether they mined their own clay.[18] Very few business records for the New York City potters have been located, and no mention of any Crolius or Remmey has been found in the sparse Morgan records.[19] We do not yet know where Crolius and Remmey obtained their clay, or whether their sources changed over time, which is likely, but it is almost certain that they knew of the existence of suitable stoneware clays before they came to New York. Harold Guilland stated that a bank of fine white clay was found in New Jersey “shortly after 1700,” and the same was found near Huntington, Long Island, and on Staten Island, but he gave no sources for his assertion.[20] New York City would have had other attractions for a stoneware potter: access to wood for firing; easy transport by water for salt and finished wares; and a growing market.

The early Crolius and Remmey potters also worked within a family setting. At least two of William Crolius’s four sons (William II and John) followed their father and Corsilius grandfather in the potting trade, as did one of John Remmey’s sons, John II. The next generation, the grandchildren of William Crolius I and John Remmey I, again included potters. The precise nature of the business relationships between these interrelated craftsmen was not recorded, but their geographical contiguity can be seen in maps.

The first map to show a pottery near the Collect Pond (a freshwater body, filled in by 1813, near the southern tip of Manhattan) is a 1730 “Plan of the Harbor of New York.”[21] A map drawn from memory by David Grim in 1813, said to show the city in 1742, has two potteries near the Collect: one slightly southwest of the Little Collect and the other a little to the northwest of the main Collect.[22] Grim labeled one of the potteries “Corselius Pottery” and the other “Remmey and Crolius Pottery,” but, on a larger-scale map, he called the former “Crolius Pottery.” Another, possibly more accurate map, of 1755, also shows two potteries but does not name their proprietors.[23]

Evidence from wills also indicates the existence of multiple kilns and workshops. William Crolius II, who died in 1778, left his kilns and equipment to his brother John’s son (John Crolius II). John Crolius I transferred his property to a younger son, Clarkson, in 1800.[24] According to the New York City directories, John II operated a shop on Pot Baker’s Hill between 1790 and 1812. Clarkson stayed at Pot Baker’s Hill until 1814, then moved his shop uptown to 67 Bayard Street.[25] The move was necessary because the neighborhood was becoming developed.

The Remmey potters had their own kiln, separate from the Crolius contingent, by at least the end of the eighteenth century. When John Remmey I died in 1762, no potting equipment or kiln was mentioned in his will, but he had previously given three hundred pounds and an enslaved person (of unknown gender but possibly a pottery worker) to his eldest son, John Remmey II.[26] Two of John Remmey II’s sons became potters. They had their own kiln by 1793, one year after their father’s death, when they leased land on Pot Baker’s Hill. It is likely that a separate Remmey kiln had been established earlier, probably under John II, since one son (Henry) in 1800 sold to the other (John III) “his moiety of the shop, kiln, tools, implements, clay, powder blue, salt, wood and whatever else did then appertain to the said premises.”[27] Henry subsequently moved to Baltimore while John III continued in New York on Pot Baker’s Hill until sometime between 1813 and 1820.[28] Members of the Remmey family later established themselves in Philadelphia and Baltimore.[29]

From the map and other information we can see that the eighteenth-century Corsilius-Crolius-Remmey potters adhered to the tradition of having several kilns operated by different masters. Sometime between 1730 and 1755, according to the maps, the works were expanded from one to two kilns. By the end of the century there were at least three kilns, two operated by Crolius potters and one by Remmey. The existence of multiple kilns has led some ceramic historians to assert that the families were in competition, but if they followed the Rhenish model, which is likely, these separate kilns were parts of a “family compound”–type of pottery works, whose members acted in cooperation with each other.[30]

The situation might have changed by the end of the families’ time on Pot Baker’s Hill. It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss the nineteenth-century potters, but it must be noted that those potters approached their craft in a different fashion than did their fathers and grandfathers. Both Clarkson Crolius and his contemporary John Remmey were men of their time who participated in the burgeoning economic life of the city as entrepreneurs as well as artisans. (Clarkson was so successful at accumulating wealth that his only surviving son, Clarkson Jr., was able to spend the last thirty-seven years of his life as a philanthropist.) Both Clarkson Crolius and John Remmey started to mark many more of their wares after they assumed control of their shops about 1800. Both used stamped marks: Clarkson’s most common mark was “C. CROLIUS / MANUFACTURER / MANHATTAN-WELLS / NEW YORK”; John Remmey’s was “J. REMMEY / MANHATTAN WELLS / N. YORK” (“Manhattan Wells” refers to a well-known landmark in New York City—the post-1800 waterworks of the Manhattan Water Company at the corner of Reade and Centre Streets.) The marks were made with stamps comprising one to three lines of print that could be used together or separately. One such stamp, in the collections of the New-York Historical Society, is made of cast lead and reads “C. CROLIUS / MANUFACTURER / NEW YORK.” The marks without “MANHATTAN-WELLS” most likely were used after the move to Bayard Street.

Excavated Materials

The stonewares excavated as part of the African Burial Ground project date to the early years of the Crolius and Remmey production. Although many later examples exist, no extant vessels have been identified as products of this early period of the Crolius and Remmey potteries. Based on documents and artifacts, the deposits accumulated sometime between the late 1720s and the mid-1760s.[31] Part of the area of the African Burial Ground had been granted to Cornelius Van Borsum in 1673 (the year that the Dutch regained control of New York before ceding it permanently to Britain) as payment for his wife’s services as a translator between the Dutch and the Algonquins. Van Borsum’s wife, Sara Roeloffse, was a remarkable woman who died in 1693.[32] Her will divided her properties among her descendants; property rights became entangled and resulted in various lawsuits that lasted into the early nineteenth century. The city also mistakenly claimed ownership of the land as part of the Commons, city-owned public land where New York’s City Hall now stands.[33]

One branch of her descendants was the Van Vleck (Van Vlack) family. The early ceramic historian Arthur Clement threw a monkey wrench into the history of New York City potteries when he read Valentine’s Manual (a gazette published during the mid-nineteenth century) for 1842, which included an illustration of the lower part of a kiln that still existed at that time under the foundations of a house “on the 5th lot from the corner of Centre and Reade Streets.”[34] Clarkson Crolius, who was quoted in the caption, said the kiln was constructed about 1730 by his grandfather William Crolius and great-grandfather Georg Corsilius. Clement, however, was of the opinion that one Abraham Van Vleck built the kiln, because he found a reference in the 1760 Minutes of the Common Council concerning the lease to Sarah and Eve Van Vleck of “three Lots of ground contiguous and adjoining to the Negroes burying place on part of which said Lots their father built a Potting House, pot oven and sunk a well, supposing at that time that said Lands were his property.”[35] It is likely, however, that the kiln was financed by Van Vleck and leased from its inception to the potters, although no documented connections between Van Vleck and any Crolius or Remmey have come to light.

Another of Sara Roeloffse’s descendants, Joseph Teller, enclosed the African Burial Ground with a fence by 1768 at the latest and used it as a pasture; he also charged a fee for its use as a burying place. It is highly unlikely that he would have allowed the potters to continue to dump there to the detriment of his pastureland. Teller’s fence was not torn down until the British occupation of New York during the Revolution. Dumping is unlikely to have occurred here after the Revolution, for this part of town developed quickly during the 1780s and 1790s as part of the city’s rapid postwar growth northward.

In addition to the documentary evidence that suggests an early date for the kiln wasters, we found none of the distinctive late-eighteenth-/early-nineteenth-century motifs that make Crolius and Remmey pots of that period so desirable to collectors. Thus, we can be reasonably certain that we are dealing with vessels and kiln furniture from the first and/or second generation of Crolius and Remmey potters.

As is to be expected with a dump site, the great majority of the sherds were from unidentifiable vessel forms. Dump sites of kiln wasters have the potential to yield extraordinary amounts of information about potters’ outputs, but they also carry their own pitfalls, especially a dump the size of the one at the African Burial Ground. Crossmending is extremely difficult, and calculating minimum numbers of vessels (MNVs) would require years of lab work. Consider the process of creating a waster pile: the kiln is opened; kiln furniture and failed vessels are taken out of the kiln and put into a wagon, wheelbarrow, or barrel, which is then trundled along and tipped out onto a spot fairly close by, in order to minimize time and effort, but not too close to the kiln or all available space would be quickly taken up.[36] The sherds are jumbled while they are taken out of the kiln and are further disordered when they are dumped. They can be disturbed again by post-depositional activities, in the present case by digging and filling in grave shafts. Moreover, the excavation strategy for this site was not designed to maximize recovery of stonewares.

The site was divided into “Areas” during the analysis. In the Southeast Area, in deposits outside the grave shafts, pottery industry by-products (stoneware wasters and kiln furniture), which comprise ninety-eight percent of all of the artifacts recovered, were found, for the most part, on the historic ground surface on which they appeared to have been dumped in piles.[37] As noted above, two large features (139 and 144), defined as irregular pits, contained concentrations of stoneware, but it was not possible to determine whether these pits were dug for pottery disposal or for another reason. Several burials were dug into and through these features after the ceramics were deposited; the grave shaft fill of these burials contained large amounts of kiln furniture and wasters. In the Northeast Area of the site, redware kiln furniture and wasters and cattle foot bones were found along with the stonewares.

The stoneware assemblage was not what we expected to find. It was unlike known late-eighteenth-/nineteenth-century wares both in the variety of forms made and the decorative motifs used. Two price lists for early-nineteenth-century Crolius wares have been preserved: one from 1804, without illustrations (Museum of the City of New York); the other, from 1809, with illustrations (American Antiquarian Society). Both lists distinguish jugs, jars, and pots. From the illustrated price list, “pots” are the equivalent of Georgiana Greer’s “wide-mouthed jars,” “straight jars” are her “preserve jars,” and “bellied jars” are her “small-mouthed jars.”[38] Of all three forms, jars, along with jugs, are by far the most common nineteenth-century vessels. Jugs and jars were used for food storage in the era before glass and metal containers became safe and inexpensive; the pitchers, kegs, oyster pots, and spouted pots (sometimes called “batter jugs” by collectors) on the Crolius price lists were also storage vessels. The other forms listed on the 1809 price list were for drinking (mugs), food preparation (churns), hygiene (chamber pots), and writing (inkstands). The “common” and “fountain” inkstands are not illustrated on the price list, but the “common” is a probably a simple round shape with holes for quills, and the “fountain” is perhaps an elaborate heart-shaped stand with removable containers for ink and sand, as illustrated by Greer.[39] Another possibility is that the “fountain” is rectangular, also with separate containers for ink and sand, as shown in Gisela Reineking-Von Bock’s Steinzug.[40]

Tables 1 and 2 show vessel forms from Germany and from the African Burial Ground. The German figures, which are from domestic deposits in the town of Duisburg, near Cologne in the Pot Bakers Land, are taken from David Gaimster’s German Stoneware.[41] Unlike the African Burial Ground numbers, they are based on vessel counts, not sherd counts. Gaimster does not give precise definitions of forms, but from illustrations it is possible to see that he uses the term jug for a round-bodied drinking vessel with a relatively narrow neck and mouth (here called a “round-bodied mug”); tankard for a more or less straight-bodied drinking vessel with a wide mouth; beaker for a round-bodied drinking vessel with a funnel-shaped neck; and pitcher for a large, round-bodied, narrow-necked vessel used for storing and decanting liquids (here called “jugs”). The difference between a drinking jug/mug and a storage jug is not clear from the text or illustrations. Porringers are small round bowls with handles used for consumption of liquid or soft foods such as porridge, gruel, or soup. Although this is a small sample from one site, it does give some indication of how forms were changing between 1400 and 1800. Most pertinent for the present study is the appearance of teawares and plates in the eighteenth century as well as the sizable increase in the number of storage jars during the same time period. Two separate trends were under way. The first affected all kinds of ceramic wares—from lead- and tin-glazed earthenwares to salt-glazed stonewares and porcelains—as ceramic tablewares in general gradually replaced metal vessels for food service and consumption. The second trend was the increased use of stoneware vessels for food storage, probably due to heightened awareness of the dangers of storing some foods in lead-glazed containers.

The Crolius and Remmey potters came out of a medieval tradition in which stoneware was a valued tableware; the early New York City products were made in a New World setting with New World clays, but they were made by German potters working within well-established craft traditions.

Mid-eighteenth-century New York City potters were making the same variety of vessel forms as their German contemporaries: forms for food consumption as well as for food storage and preparation. The form proportions are similar in the Duisberg vessels and the African Burial Ground sherds. Storage jugs and jars were the most common types (figs. 5-7), although we must be cautious about how we interpret the relative numbers of jugs versus jars: it is easier to identify jugs from body sherds, as there is a distinct interior angle where the potters pulled the body in at the jug shoulder, and jug sherds frequently have light or no salt glaze on their interiors, because their necks were restricted and during firing were encased in jug stackers.

The majority of the unidentified hollowwares in the African Burial Ground collection were probably also from jugs and jars of various sizes. Jugs and jars in this collection both had lower bodies that taper to the base, so generally it was not possible to distinguish between the two.

The porringer was the next most common identifiable form (fig. 8). Porringers made of lead-glazed red earthenwares are fairly common on eighteenth-century archaeological sites, but stoneware examples are rare. Nevertheless, porringer sherds were common in this assemblage, and some vessels were whole or nearly so. Round vessels with one handle were the most common, but a few straight-sided ones were found (fig. 9).

Conversely, the tankard (also called a “straight-sided mug”) is a well-known stoneware vessel form in archaeological and museum collections (fig. 10); it is the most likely vessel type to have incised and filled-in decoration (fig. 11). Many American archaeologists have assumed that any vessel with incised decoration had to be a German-made import, but obviously this is not true. Probably because they were sturdy and kept drinks cool, stoneware tankards continued to be made well into the nineteenth century. These drinking vessels tended to be much more elaborately decorated because they were used on the table and instrumental in communal, often convivial, social settings.

Plates and dishes were also forms that we did not expect to find. The term dishes here refers to round vessels that are deeper than plates but not as deep as pans; they often have a small rim (fig. 12). Most dishes were decorated with simple brushed blue motifs, but a few were undecorated. The plates had simple brushed motifs around their rims and also sometimes on their bodies (fig. 13).

Although only four sherds were identified as teawares, they were very distinctive. Both the saucer and the teacup sherds (lost on September 11 before they could be photographed) were base fragments made in the same Chinese-derived shapes commonly found on English white salt-glazed teawares (i.e., hemispherical vessels with tall, cutout foot rings). The saucer’s exterior was covered in a brown slip, probably in imitation of Batavian ware (Chinese porcelain with brown slipped exteriors). The two sherds that mend to form a round teapot spout were undecorated but clearly were molded rather than turned; they broke along the mold seams (fig. 14).

Rim forms on porringers, tankards, and plates did not exhibit much diversity, but jars had a variety of rim shapes. The most common form had a flat top and rounded exterior above slight constriction (fig. 15). The variations seen in particular vessel profiles indicate that the potters used several templates to form them (fig. 16). None of the jar rims appeared to be fitted for a lid; in fact, only twenty-four sherds in the entire collection were identified as parts of lids.

In most cases the top part of jug and chamber pot handles were attached immediately below the rim (fig. 17, see fig. 5). Jar handles were generally horizontal loops attached to the body with wide, flattened ends (see fig. 2). Handle attachments on jars, jugs, and chamber pots frequently were outlined in blue. Two sherds, probably round-bodied mugs or small jugs, had rat-tail lower handle attachments outlined in blue that emphasized their V shape (fig. 18). Horizontal handles were essentially round or oval in cross section whereas vertical handles on the larger vessels were ridged (fig. 19).

The only marked piece was an odd, nearly complete vessel with the letters “IS” or “SI” scratched onto the bottom (fig. 20). Crudely made in comparison to the rest of the collection and similar in form to period ointment jars, in stoneware this object is like nothing else we found, and it is tempting to imagine that it was made by an apprentice or as some sort of test or marker piece for the kiln.[42]

If the vessel forms at the African Burial Ground were surprising, the types of decoration were downright astounding. Approximately one-fourth of the sherds from the nonburial contexts were decorated, but almost half simply had traces of unidentifiable brushed-on motifs. The first surprise was the prevalence of a spiral motif on a number of jars and jugs (fig. 21). This motif (also called “watch spring”) has long been associated with the pottery financed by the New Jersey Morgan family. The association is quite strong because it is derived from sherds excavated at the pottery site by Robert Sim, the pioneering scholar of New Jersey stonewares.[43] The Morgan pottery was in operation before the Revolution, probably as early as 1768.[44] The anonymous potter(s) employed by the Morgan family might well have learned or worked the craft in the New York City potteries and brought the motif to New Jersey. Many pots heretofore identified as Morgan products, based on their spiral motifs, were probably actually made in New York. (For extensive discussion and analysis of the Morgan pottery site, see “The Eighteenth-Century New Jersey Stoneware Potteries of Captain James Morgan and the Kemple Family” by Arthur Goldberg, Peter Warwick, and Leslie Warwick, pp. 2–40 in this volume.)

There were several variations on the spiral motif in the African Burial Ground collection. The most common was part of decoration centered on handle attachments (fig. 22). Another was a variation that we called “spiral butterfly,” in which brush strokes were added between the spirals (fig. 23). Most of the identified spiral butterflies were on jars. During a recent conference at the New Jersey Historical Society, Brenda Springsted showed slides of sherds excavated at the site of the eighteenth-century Kemple pottery in Ringoes, New Jersey, that were decorated with notches or “eyelashes” coming off the main spiral.[45] The audience and speakers hypothesized that this particular variation might be a defining characteristic of Ringoes pots, but shortly thereafter a sherd with the same motif was identified from the African Burial Ground (fig. 24). Springsted’s research has established that Kemple worked for a time in New York City, most probably with Crolius and/or Remmey, before he established his own family-run shop in the hinterlands of New Jersey. This suggests that a New York–associated potter took his decorative repertoire with him when he left the city to establish a pottery in the country.

Other sherds were decorated more simply. The most easily identifiable motif in the collection was a simple brushed circle around handle attachments, often seen in association with other brushed-on designs, especially the spiral, as in figures 21 and 22. Another common motif, found on a variety of vessel forms, was cordons filled in with blue (see, for example, figs. 10, 11).

Brown slip, used to create mottled brown exteriors reminiscent of Rhenish brown stonewares, was seen on approximately six hundred sherds. Often the slip was on the top part of jugs (fig. 25) and sometimes was used in combination with brushed blue decoration, a somewhat unattractive pairing (see fig. 12). One mottled brown jug sherd had an unidentifiable incised design that appeared to be similar to a jug attributed to a Remmey potter that is now in the Museum of City of New York (fig. 26). A few tableware sherds were covered with a solid brown slip, as seen in the plate fragments illustrated in figure 27, which also have part of an incised motif.

More complex designs were made by incising motifs and filling in sections with blue, as seen in figure 11. Incised and filled-in motifs were found most frequently on tankards of various sizes, although they were also identified on jugs and jars. Many of the excavated sherds with incised designs were very small, making it difficult to identify motifs, but those that could be identified were geometric and floral designs (fig. 28). One large sherd had an incised floral motif that had been left uncolored, probably inadvertently (fig. 29). The cordons around the base were already painted blue, probably an indication that a different mixture of cobalt was used for simple brushed lines/motifs than for filled designs. This supposition is supported by the appearance of some sherds: the blue color on filled-in incised motifs is almost always thicker and more brilliant than the blue in simple brushed motifs. Twelve sherds had purple as well as blue coloring used for both incised and brushed motifs (figs. 30, 31). The purple color often had a muddy brown cast. One small jar, among the vessels lost on September 11, had either very muddy purple or brown slip filling in an unusual star motif (fig. 32).

A few stamped sherds were identified. Floral stamps were common on later Crolius and Remmey wares but apparently not on midcentury vessels, although the stamp used on the jug or jar sherd illustrated in figure 33 was the same or very similar to the one used on the later Barclays Bank jar.

The most unusual pieces in this collection were two small sherds with sprigged decorations (figs. 34, 35). Sprigged decorations are small motifs formed in a mold and then applied to a partially dried vessel. The most common sprigged motif found on eighteenth-century German vessels made for export is a medallion with the initials “GR” surrounded by an elaborate border. (“GR” stood for Georgius Rex—George I, II, or III of Great Britain). GR mugs are common on eighteenth-century British colonial archaeological sites and have been attributed to Germany. Nevertheless, we now know that American stoneware potters were also making them. A few nineteenth-century Crolius and Remmey vessels have sprigged decorations,[46] but the present excavations have shown that the potters were making their own version of eighteenth-century GR vessels. These sherds undoubtedly are products of the New York potteries—they are very underfired and unglazed and thus are obvious kiln wasters. Their interiors have a pink-purple slip, probably an underfired version of the common pink-brown interiors of better-fired vessels. Georg Corsilius or Johan Crolius or Johannes Remmey might have brought the mold for this medallion with them when they emigrated, or they might have made it or had it made here, or they might have taken a cast from an imported vessel to create a copy.

One relatively common decoration found on approximately thirteen percent of all sherds from a variety of vessel forms in the African Burial Ground collection—but not identified on later Crolius and Remmey wares, to the best of my knowledge—was rouletting. There were many rouletted patterns. The marks seen in figure 36 could have been made by holding a small wooden wheel or spool, cut with a simple design, against a damp pot as it revolved on the potter’s wheel,[47] but many of the patterns run diagonally. Some patterns were deeply impressed, although the salt glaze has obscured them. On porringers the patterns are often delicate, in keeping with the small size of these vessels (fig. 37). Patterns on jars (fig. 38), jugs (fig. 39), and chamber pots (fig. 40) were larger. No tankard sherds with rouletted patterns have been identified.

The most complete example of vessels with rouletting were sherds from at least five jugs with what we called “zoned” decoration (fig. 41). These vessels, all lost on September 11, had wide bands of rouletting, sometimes separated by blue bands; the rouletted bands had different patterns, usually slanting in opposite directions.

Even though the African Burial Ground “zoned” jugs had much simpler decoration, they call to mind seventeenth-century German jugs on exhibit in the ceramic museum at Hohr-Grenzhausen and illustrated in Reineking-Von Bock.[48] At least to my eye, the New York ones are lineal descendants of these vessels with their partitioned motifs.

I had not remembered seeing any rouletted vessels in New York City collections (and this could be due at least in part to the scarcity of mid-eighteenth-century collections in the city), but now that we have identified their attributes they are starting to turn up. So far they have been found in eighteenth-century archaeological assemblages from Somerset and Raritan Landing, New Jersey, and Connecticut.[49]

Several sherds have unique decorations. One small rim sherd, possibly from a tankard, has a brown slip line around the rim that is reminiscent of the brown line around the rims of slip-dipped white salt-glazed English tankards (fig. 42). This was probably a deliberate attempt by the New York potters to imitate a popular English form. Another small rim sherd has blue dots atop its rim; a base sherd with the start of a handle attachment was probably from the same vessel (fig. 43). The vessel has a slightly rounded rim, rather than the thin, flaring rim of porringers, but might have been a porringer variation or a small handled bowl.

The New York City potters used slips on the interiors of some vessels, in particular jugs. The colors ranged from rose-brown through red-brown to light, medium, and dark brown (fig. 44). The variations in slip colors are most probably due to firing conditions—that is, the precise heat of each part of the wood-fired kiln and the degree of oxidization or reduction. These are not Albany-type slips (common on nineteenth-century stonewares): their color is lighter and the slips are thinner. The composition of the Corsilius/Crolius/Remmey slips has not been determined, but it is likely that they were made from local clays.

The sherds from the African Burial Ground have shown researchers three things. First, a greater variety of vessel forms were produced in the eighteenth century than in the nineteenth; the potters’ German training, and possibly a desire to imitate the new English white salt-glazed wares, led to the production of table- and teawares that were not made in later years. After about 1760–1770 easily obtained, relatively durable, and decorative refined earthenwares (creamwares, pearlwares, and whitewares) were preferred for table- and teawares. Second, at least some of the Corsilius, Crolius, and Remmey potters were skilled decorators who produced ornamented wares that we archaeologists have been incorrectly identifying as German. Third, motifs on preindustrial pottery cannot simply be assigned to one workshop: we do not know enough about the migrations of workmen between shops. It is obvious that ideas, and probably people, moved from place to place within the southern New York–New Jersey region.

With the publication of these fragments, archaeologists, curators, and collectors will be able to better identify the products of these early New York City stoneware potters. As more comparative information from extant New York City pieces and additional archaeological research from the New Jersey pottery sites become available, a more complete understanding will emerge of the important role these immigrant Germanic potters had on the early history of American stoneware production in this region.

Rebecca Yamin, ed., “Tales of the Five Points: Working Class Life in Nineteenth-Century New York,” report prepared for Edwards and Kelcey Engineers, Inc., and General Services Administration, Region 2, New York, from John Milner Associates, Inc., West Chester, Pa., 2002.

Charles D. Cheek, ed., “290 Broadway: Changing Land Use at Lower Manhattan’s African Burial Ground, Vol. 1,” report prepared in 2006 for Edwards and Kelcey Engineers, Inc., and General Services Administration, Region 2, New York, from John Milner Associates, Inc., West Chester, Pa. (forthcoming); Warren Perry, Jean Howson, and Barbara Bianco, eds., “The New York African Burial Ground Archaeology Final Report,” The African Burial Ground Project, Howard University, Washington, D.C., report prepared for the United States General Services Administration Northeastern and Caribbean Region, 2006.Charles D. Cheek, ed., “290 Broadway: Changing Land Use at Lower Manhattan’s African Burial Ground, Vol. 1,” report prepared in 2006 for Edwards and Kelcey Engineers, Inc., and General Services Administration, Region 2, New York, from John Milner Associates, Inc., West Chester, Pa. (forthcoming); Warren Perry, Jean Howson, and Barbara Bianco, eds., “The New York African Burial Ground Archaeology Final Report,” The African Burial Ground Project, Howard University, Washington, D.C., report prepared for the United States General Services Administration Northeastern and Caribbean Region, 2006.

Louis Berger and Associates, Inc., “Druggists, Craftsmen, and Merchants of Pearl and Water Streets, New York: The Barclays Bank Site,” prepared for London and Leeds Corporation, N.Y., and Barclays Bank PLC, N.Y., by the Cultural Resource Group, Louis Berger and Associates, East Orange, N.J. (1987). Meta F. Janowitz and Bradford Botwick, “Crolius and Remmey Families of Pott Baker’s Hill” (paper, annual meeting of the Council for Northeast Historical Archaeology, Troy, N.Y., October 1986).

Anne-Marie Cantwell and Diana diZerega Wall, Unearthing Gotham: The Archaeology of New York City (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), pp. 277–96.

See illustrations in, for example, Donald Blake Webster, Decorated Stoneware Pottery of North America (Rutland, Vt.: Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1971); Georgiana Greer, American Stonewares: The Art and Craft of Utilitarian Potters (Exton, Pa.: Schiffer Publishing, 1981); and William C. Ketchum Jr., American Stoneware (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 1991).

For an example of the work of a Manhattan-trained potter, see Ellen Paul Denker, “Ceramics at the Crossroads: American Pottery at New York’s Gateway, 1750–1900,” Staten Island Historian 3 (1986): 21–36.

Greer, American Stonewares, p. 19.

Previous researchers identified Georg Corsilius as emigrating from Nieuw Wit (Neuwied), a town on the Rhine near Koblenz (see, e.g., William C. Ketchum Jr., Potters and Pottery of New York State, 1650–1900 [Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1987], pp. 40–41). Research by a German genealogist, however, located Georg Corsilius in the town of Nordhofen, in the former duchy of Wied-Neuwied (letter of April 1982 from Dr. Franz Baaden to John S. Monagan, a direct descendant of Georg Corsilius through his great-grandson George Crolius. A copy of the letter was generously given to the author by Monagan’s wife, Rosemary.) Nordhofen is to the northeast of Koblenz; there were few potters in the town of Neuwied but many in the duchy. Parish records list Georg as a godfather in 1717; his daughter Veronica is noted as a godmother in 1718. The records also state (although the date of this entry was not noted in Baaden’s letter) that Georg’s allotted seat in the church was no longer occupied by him “because Georg Corsilius with his family have moved to America.” Baaden advanced the idea that Veronica Corcelius and Johann Willem Crolius were half siblings who married and that the Crolius name is simply a variation of Corsilius. The simplification of name might well be true, but it does not follow that Veronica and Johann were this closely related, even though Veronica (born 1697) was a daughter of Georg by his first wife and there was a son named Johann Willem (born 1706) from his second marriage. Nevertheless, Baaden’s researches found another Johann Willem Corsilius, a nephew of Georg. Baaden eliminated him from consideration because he was married in 1714 in Germany, but unless his death record is found in Germany we can hypothesize that he might have been widowed and followed his uncle to America. Cousin marriage was not uncommon before the twentieth century. Alternatively, the Johann Willem Crolius who married Veronica might simply have been invisible in Baaden’s research.

Joachim Naumann, “Deutsches Steinzug des 17.–20. Jahrhunderts,” Beiträge zur Keramik 1 (Düsseldorf: Het Jens-Museum, Deutsches Keramikmuseum, 1980). Greer, American Stonewares, p. 13.

See note 8 above.

Dr. Franz Baaden to John S. Monagan, April 1982; copy in the possession of the author.

Exhibit panel, Töpferei Museum, Raeren.

David Gaimster, German Stoneware, 1200–1900: Archaeology and Cultural History (London: British Museum Press, 1997).

Ibid., p. 48.

Carl Bridenbaugh, The Colonial Craftsman (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1950), p. 68.

Ketchum, Potters and Pottery, p. 40. A freeman was a citizen who was qualified to conduct business or practice a craft.

Laurel Ann Racine, “Re-examination after Excavation: The Problems of Attributing Wares to Three New Jersey Stoneware Makers” (master’s thesis, University of Delaware, 1997), pp. 5–6.

The Commons, not far from Pot Baker’s Hill, was a source of clay, but the Commons clay was probably red clay used for earthenware vessels and for bricks (Valentine’s Manual of Old New York [1924], pp. 238, 240). It is possible that stoneware clay outcropped on Manhattan before the island was developed, as the clay-bearing geological formation runs through the island, but the potters could have dug their own clay elsewhere in the metropolitan region.

Racine, “Re-examination after Excavation.”

Harold F. Guilland, Early American Folk Pottery (Philadelphia: Chilton Book Company, 1971), p. 40.

I. N. Phelps Stokes, The Iconography of Manhattan Island, 1498–1909, 6 vols. (1915–1928; Union, N.J.: Lawbook Exchange, 1998), vol. 1, The Period of Discovery (1524–1609), pl. 27a. For more on the Collect Pond, see Kenneth T. Jackson, ed., The Encyclopedia of New York City (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1995), p. 250.

Arthur W. Clement, “New Light on the Crolius and Remmey Potteries,” American Collector 9 (1946): 10.

Stokes, Iconography, pl. 34.

Ketchum, Potters and Pottery, pp. 46–47.

Ibid., p. 50.

Ibid., p. 51.

Ibid.

Ibid., pp. 52–53.

Edwin Atlee Barber, Pottery and Porcelain of the United States (1893; reprint, New York: Feingold and Lewis, 1976), p. 561; and Ketchum, Potters and Pottery, p. 52.

Guilland, Early American Folk Pottery, p. 40, for example, states that the Remmey pottery “remained in competition with the Crolius Pottery until 1820.”

Perry et al., “African Burial Ground Archaeology Final Report.” Information about ownership of the African Burial Ground was compiled by Jean Howson.

Meta F. Janowitz, “Sarah Roeloffse in Fact and Fiction” (paper, annual meeting of the Society for Historical Archaeology, York, England, January 2005).

Cantwell and Wall, Unearthing Gotham, p. 329 n. 5.

Clement, “New Light,” p. 10.

Ibid., p. 22.

For the most part kiln refuse is a nuisance, but it can be a welcome addition to areas that need fill. It is perhaps surprising that no concentrations of stoneware wasters have been identified, to this author’s knowledge, in the eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century landfills that have been excavated along the East River in New York City.

Meta Janowitz and Charles D. Cheek, “The New York Ceramic Industry and Its Use of the Burial Ground,” in Cheek, “290 Broadway.”

Greer’s American Stonewares illustrates common stoneware forms, providing a standardized way to refer to different vessel forms. Greer’s terms were used during the analysis of the African Burial Ground collection.

Greer, American Stonewares, p. 19.

Gisela Reineking-Von Bock, Steinzug, exh. cat. (Cologne: Kunstgewerbemuseum der Stadt Köln, 1971), nos. 719–725, 730.

Gaimster, German Stoneware, p. 121.

A stoneware ointment pot probably made in New York was recently identified by the author in the archaeological assemblage from the 175 Water Street site, formerly housed at South Street Seaport and now at the New York State Museum, Albany.

James R. Mitchell, “The Potters of Cheesequake, New Jersey,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Ian M. G. Quimby (Charlottesville, Va.: University Press of Virginia, 1973), pp. 319–38.

Racine, “Re-examination after Excavation.”

Brenda L. Springsted, “Stoneware Made in the 18th Century ‘Hinterlands’ of Ringoes” (paper, “Early Stoneware in New Jersey and New York: Origins of an American Industry,” the first symposium of the Potteries of Trenton Society, 2004).

The most famous is an Albany slip-glazed covered pitcher or coffeepot in the collection of the New-York Historical Society (acc. no. 1926 16a) that was elaborately decorated with flowers and leaves.

Daniel Rhodes, Stoneware and Porcelain: The Art of High-Fired Pottery (Radnor, Pa.: Chilton Book Company, 1959), p. 74.

Reineking-Von Bock, Steinzug, nos. 433–442.

Somerset, New Jersey: Richard Veit, personal communication, 2005; Raritan Landing, New Jersey: author’s observation during analysis of the artifacts from 2001 excavations at this site; Connecticut: Roberta Charpentier, Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center, personal communication, 2003.