Oval dish, Cork and Edge, Newport Pottery, Burslem, ca. 1846–1860. Whiteware. L. 14", W. 8 1/2". Printed mark: “C & E.” (N. Ewins Collection.)

Soup plate, Cork and Edge, Newport Pottery, Burslem, ca. 1846–1860. Whiteware. D. 8 3/8". Printed mark: “VERONA / CORK & EDGE.” (Courtesy, Barker-Goodby Collection.) Another version of the Verona pattern is shown in fig. 14.

Detail of the mark on the soup plate illustrated in fig. 2.

Side plate, Cork and Edge, Newport Pottery, Burslem, ca. 1846–1860. Whiteware. D. 6 5/8". Printed mark: “Cork & Edge / Hong.” (Courtesy, Barker-Goodby Collection.)

Dinner plate, Cork and Edge, Newport Pottery, Burslem, ca. 1846–1860. Whiteware. D. 10 1/4". Printed mark: “Cork & Edge / Vermicelli.” (Courtesy, Barker-Goodby Collection.)

Jug with mocha and banded decoration, Edge, Malkin and Company, Newport Pottery, Burslem, ca. 1870–1902. Whiteware. H. 5 5/8". Printed mark: “TRADE MARK / EDGE, MALKIN & CO. LTD / BURSLEM.” (Courtesy, Potteries Museum and Art Gallery, Stoke-on-Trent.)

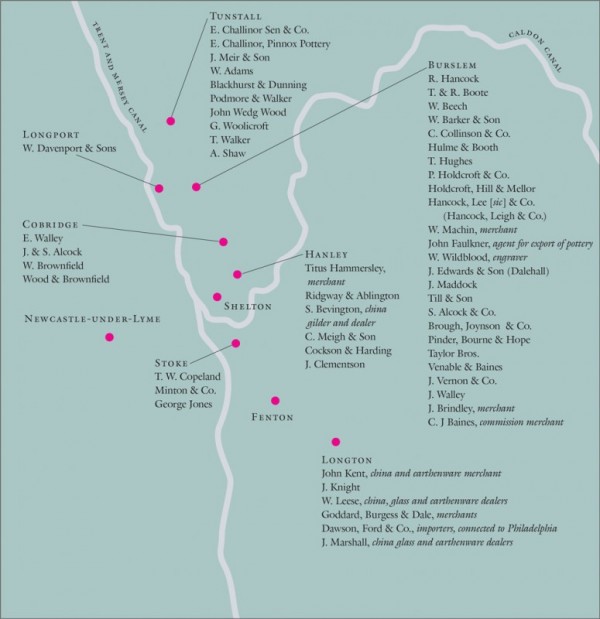

Staffordshire manufacturers and merchants supplied by Cork and Edge with ceramics from 1848 to 1860. The names provided are manufacturers, unless otherwise stated.

Customer Distribution of Cork and Edge of Burslem, 1848–1860. A large cluster of crockery dealers was in the nearby districts of Manchester and Leeds.

Customer Distribution of Cork and Edge, 1848–1860. Map showing crockery dealers and manufacturers located throughout Great Britain.

Customer Distribution of Cork and Edge, 1848–1860. Map showing crockery dealers located in continental Europe.

Customer Distribution of Cork and Edge, 1848–1860. Map showing crockery dealers located in Canada and the United States.

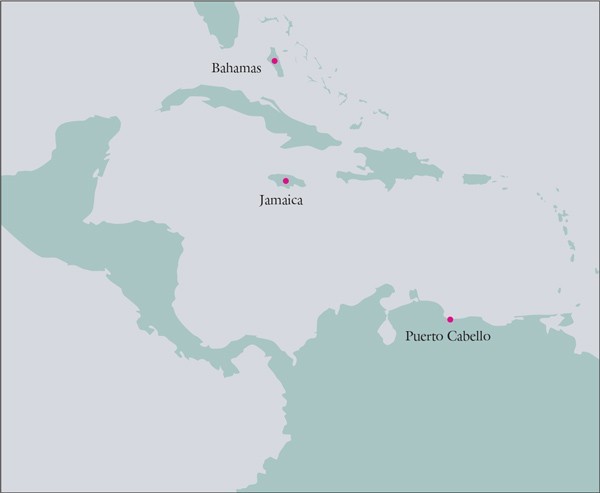

Customer Distribution of Cork and Edge, 1848–1860. Map showing customers located in South America and the West Indies.

Customer Distribution of Cork and Edge, 1848–1860. Map showing customers located in Australasia.

Plate, Cork and Edge, Newport Pottery, Burslem, ca. 1846–1860. Whiteware. D. 9 1/2". Printed mark: “Verona / Cork & Edge.” (N. Ewins Collection.) Compare this example with the soup plate illustrated in fig. 2, also marked “Verona.”

Two-handled mug with flow blue decoration, Cork, Edge and Malkin, Newport Pottery, Burslem, ca. 1860–1870. Whiteware. H. 3 3/4". Printed mark: “Singa CE & M.” (N. Ewins Collection.)

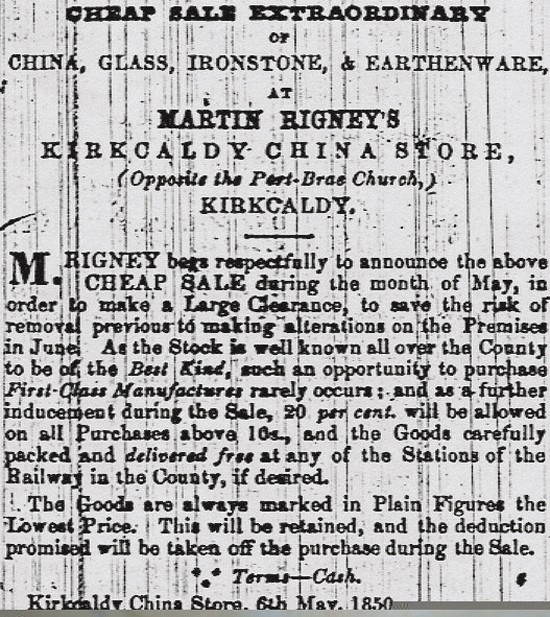

Advertisement, Fifeshire Advertiser, May 18, 1850, for Martin Rigney’s “Kirkcaldy China Store,” Kirkcaldy, Scotland.

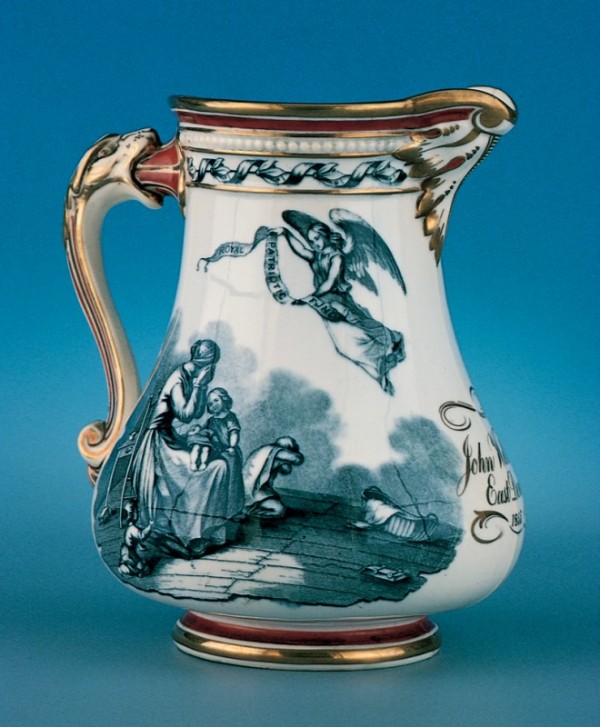

Jug, Samuel Alcock and Co., Burslem, ca. 1855. Porcelain. H. 8 1/4". (Private collection.) Portrayed on this Royal Patriotic Fund Crimean commemorative jug are a printed battleground scene and a domestic scene with a widow and her children.

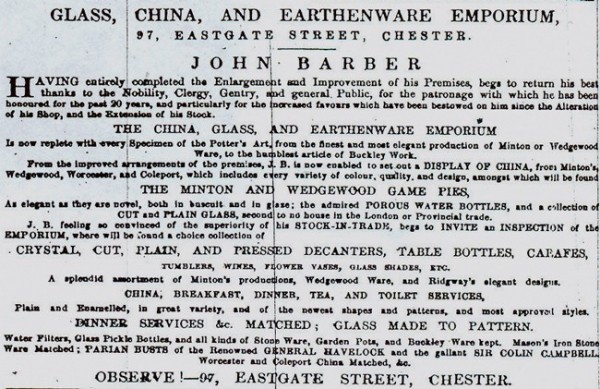

Advertisement, Chester Chronicle, June 5, 1858, for John Barber’s “Glass, China, And Earthenware Emporium,” Eastgate Street, Chester, England.

The availability and consumption of nineteenth-century ceramics have received greater scrutiny in the United States than in Britain.[1] British research has focused on the production side of ceramics, and most distributional studies have extended only as far as the eighteenth century.[2] Those of the nineteenth century have attracted some attention in recent years, yet it has remained surprisingly difficult to contrast the ceramics sold by crockery dealers in different parts of Britain with those in the United States.[3]

In 1997, in an article entitled “‘Supplying the Present Wants of Our Yankee Cousins...’: Staffordshire Ceramics and the American Market, 1775–1880,” I examined the American ceramic market in terms of merchandising, competition, and other socioeconomic factors.[4] The basic tenet of my article was that by the mid-nineteenth century American ceramic demand significantly diverged from that of the British. Based on this observation, the dialogue among manufacturers, merchants, and retailers was explored. Having greater comparative data from the British perspective, however, would have clarified the extent of the divergence. This type of research might also help to interpret British domestic sites, as archaeology begins to examine the nineteenth century in more detail.

Certain types of nineteenth-century ceramics that were manufactured in Britain are well known in the United States. For instance, there are the widely collected dark blue–printed wares with American scenes and political subjects made in the 1820s. The flow blue, flow mulberry, “tea-leaf,” and white ironstone wares exported beginning in the 1840s have entire organizations devoted to their study in the United States, whereas in the United Kingdom they cannot be found in significant quantities in private collections or in museums.[5] Does this in itself indicate that differing tastes existed between Britain and the United States, or are other factors at work that should be considered as well?

Aside from the issue of what survives in private collections or museums, differences between British and American ceramic demand need to be examined further. Drawing conclusions from the extensive archives of such prestigious firms as Wedgwood, Spode, and Minton and Company is problematic as they provide a picture of demand decidedly skewed toward the upper echelons of society, a fact confirmed by detailed studies of their marketing strategies.[6] The Staffordshire manufacturers that produced ordinary, mainstream ceramics, however, are not as well documented.

An important exception is Cork and Edge of Burslem, later known as Cork, Edge and Malkin.[7] The archive material of this company includes a sales ledger for 1848–1860 that gives the name and address of each customer as well as the value of each sale.[8] An account book for 1857–1863 provides the name (though not always the address) of each customer, the value of the sale, and a brief description of the goods if sold to foreign customers.[9] Despite their overlapping dates, it was decided not to amalgamate these two sources of information because the high number of missing addresses in the account book could distort findings regarding customer distribution. A useful daybook for 1860–1861 provides the names of the buyers, itemizes the goods purchased, and lists the selling prices.[10] The last source of documentation is the correspondence of Cork, Edge and Malkin between 1863 and 1867, which consists of 332 letters of inquiry and orders.[11]

Compared with manufacturers such as J. Ridgway of Hanley or Minton and Company of Stoke, Cork and Edge was not a vast firm, employing 325 people in 1861, although it was comparable to firms extensively connected with the American trade.[12] Enoch Wedgwood of the Unicorn Works, Tunstall, for example, employed 380 persons in 1861.[13] Cork and Edge is a good example of a middle-range firm whose mainstream production was ordinary earthenware, a fact confirmed in a letter by Matilda Whittle of 111 Adelphi Street, Preston, who wrote to them in 1867, “In answer to my last you state that you don’t make china . . . .”[14]

Extant pieces demonstrate the relative quality of wares made by Cork and Edge. For instance, a large oval dish marked “C & E” (fig. 1) is printed with the well-known Asian Pheasant design. Other wares typically made by the firm include a soup plate entitled “Verona” (figs. 2, 3), a side plate with printed and enamel decoration entitled “Hong” (fig. 4), and a dinner plate entitled “Vermicelli” (fig. 5). All these examples date from circa 1846–1860, whereas a jug with mocha decoration marked “Edge, Malkin & Co. LTD” dates from circa 1870–1902 (fig. 6).

Buyers and Distribution

Cork and Edge supplied a striking number of other manufacturers and merchants in the Staffordshire region (fig. 7)—prestigious manufacturers such as Copeland and Minton and Company of Stoke, and even the Seacombe Pottery, Liverpool, the Wear Pottery, Southwick, Sunderland, and the St. Peter’s Pottery, Newcastle-upon-Tyne.[15] Also listed as a customer was the Annfield Pottery in Glasgow, but rather than the usual “To Goods” entry, it was sent two dozen “lawns” in 1848 and 1849.[16]

The customer distribution of Cork and Edge from 1848 to 1860 is revealed in the company’s records. A large cluster of crockery dealers was in the nearby districts of Manchester and Leeds (fig. 8), yet customers were spread throughout England, Scotland, and Wales (fig. 9). No Scottish customers were listed after 1853. The distribution maps do not show a surge of orders in the mid-1860s from the West of England and South Wales coinciding with an agent traveling in that area.[17]

According to Lorna Weatherill’s investigation of Staffordshire factories in the mid-eighteenth century, most of the British buyers were located in London.[18] Neil McKendrick analyzed Josiah Wedgwood’s papers to support a thesis of London being the hub of a filter-down effect of taste and demand. As he argued, Wedgwood’s London showroom was part of a marketing strategy designed to attract the wealthy, thus securing prestige and encouraging emulation by other classes and by provincial society.[19]

One hundred years later this model appears not to apply to Cork and Edge, who listed fifty customers located in Liverpool, forty-one in Manchester, twenty-nine in London, twenty-six in Birmingham, and nine in Edinburgh. Most locations in which Cork and Edge sold its wares had fewer than four customers—Dublin and Leeds, for example, had four, and Bristol had two. In the nineteenth century, many of Cork and Edge’s Liverpool customers were involved in international markets.[20] Manufacturers on the scale of Cork and Edge, however, did not operate a London-based trade, even though they exhibited at the Great Exhibition of 1851 and at the Paris Universal Exhibition of 1855, so one must be careful not to extrapolate an overriding filter-down theory from the archives of exceptional manufacturers such as Wedgwood and Minton.[21]

The customer distribution of Staffordshire manufacturers was geographically wide in the eighteenth century, but by the nineteenth century firms like Cork and Edge were also dealing directly with Continental Europe, Canada, the United States, South America, the West Indies, and Australasia (figs. 10-13).[22] For Cork and Edge a direct trade with the markets farther afield developed in the mid- to late 1850s. Sales to Jamaica first occurred in 1856, to the Bahamas in 1855, and to Puerto Cabello, Venezuela, in 1856. In 1867 Cork and Edge received an order from J. Van Hees of Amsterdam requesting, among other wares, blue and green printed tableware in the Verona pattern.[23] (Another version of the Verona pattern is illustrated in figure 14.)

Customer distribution was not limited to retailers and merchants. The first references to Australasian customers are to the Reverend Walter Lawry, located at Parramatta, west of Sydney, who was sent goods in 1855 and 1856, and the Reverend Henry Lawry of Hokianga, New Zealand, recorded in 1859.

As they were in the eighteenth century, women continued to be involved in the crockery trade.[24] Unlike in most other trades, women played an important part in the crockery trade, as their gender was viewed as advantageous to selling ceramics.[25] The Cork and Edge sales records mention Isabella Johnson of Leith in 1849; Sarah and later Mary Farrer of Halifax from 1848 to 1860; Mary Ann Walker of Bolton from 1850 to 1853; and Elizabeth Dunbar, High Park Road, Toxteth, in Liverpool from 1851 to 1860.[26] On the Continent were the “Sisters Defrees” of The Hague, mentioned in 1853. It was not unknown for a widow, through necessity, to carry on her late husband’s business.[27] For example, J. G. Hawley of Bristol, who acted as the West Country traveler and agent for Cork and Edge, wrote of J. C. Davis of Neath, South Wales, in 1866: “Mrs Davis late ‘J.C. Davis, his [sic] dead’ wants this order completed soon as you can[,] exact as order[e]d—she [is] left with 7 children and will keep on the business.”[28]

The wares sold by Cork and Edge were not necessarily made by it. Just as Cork and Edge supplied other manufacturers with goods, it also obtained wares to fill orders. An order for tableware from J. Gould of Ilminster, Somerset, was supplemented with a china comport from Minton, at a total cost of 4s. 4d., including 3d. for the messenger who delivered the item to Cork and Edge. Dessert plates were purchased from Wedgwood for E. Dukes of Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, and twelve buff muffins were acquired from Copeland for H. Truby, a dealer at Bicester, Oxfordshire. The need to supplement their own manufactured wares to complete orders provides a more rounded picture of nineteenth-century provincial ceramic demand.

Ceramic Demand

An examination of a selection of goods supplied by Cork and Edge to certain crockery retailers serves to illustrate various aspects of social, domestic, and economic life in the second half of the nineteenth century. Orders sent in the 1860s from West Country buyers in towns such as Wells and Shepton Mallet were for a broad spectrum of goods. Dinnerware (plates, dishes, tureens) and teaware (teapots, creams, cups, and saucers) were usually decorated. Other goods ordered were toilet ware (chamber pots, ewers, basins, and soap and brush trays) and more unusual items, such as bedroom candlesticks, tall or pillar candlesticks, porter mugs, CC (cream-colored) wine mugs, and CC “blancmanges.” Chamber pots could be plain or decorated, and CC goods tended to be serviceable items, such as chair pans, jugs, and bakers.

There were extremes, however, as was found from the evidence of New York newspaper advertisements referring to Staffordshire goods.[29] A customer in Kensington Gardens, London, ordered from Cork and Edge a very exceptional dinner service (186 pieces) with a painted crest in turquoise and gold that cost £78.14.2—£15.10s. of which was the cost of decoration.[30] Expensive items were, for the most part, destined for London, but this does not mean that they were precluded from the provinces or that inexpensive goods were not sent to the city. In 1861, for instance, J. H. Rudall Esq. of London purchased a whole order of CC table-, tea-, and toilet ware for a mere £2.5.4.

Ceramic consumption at this lowest economic level is exemplified when, in response to Cork and Edge’s letter to “please return the matchings” (which included two ewers and one chamber pot), Raymond of Yeovil, Somerset, replied, “the articles named . . . being quite useless and not worth the trouble of sending back, they were crack’d & holes through, consequently were disposed of to some poor person in a trifle.”[31]

Anglo-American Comparison

The crockery dealer Lewis of Wantage (located fifteen miles southwest of Oxford), ordered 1 1/2 dozen five-inch plates, described as “Wantage Church & School,” for 1s. 4 1/2d.[32] The rest of the printed ware in this order amounted to £4.7.7 1/2 and apparently was not specialized.[33] In the case of Miss Humphries, a crockery dealer in Chippenham, Wiltshire, the traveler noted at the bottom of her order: “Wanted immediately exact as ordered also copper plates to be set Chippenham Church.”[34] Were vessels printed with the titles of institutions rather than actual images? There is a distinct possibility, based on other correspondence in the Cork and Edge archive, that often titles and names of places were used.[35] However, the October 1861 purchase by crockery dealer Samuel Davis of Weymouth, Dorset, of six toast racks (“P[earl] white”), six bed candlesticks, and twelve tall candlesticks, all drab gilt, plus five dozen CC chamber pots and one set toy teas brown goat, also included jugs described as “Weymouth Views.” The jugs cost 1s. 8d. and the “Views” certainly implies imagery.[36]

It is harder to imagine why, on July 15, 1861, crockery dealer E. Bowers of Dartmouth, Devon, purchased for 1s. 9d. six sauce ladles decorated with “Blue American Views.” While this purchase of American views represents only a small portion of the order, which totaled £12.7.7,[37] it does suggest interesting consumer preferences. Is it possible that, given the advent of the Civil War that year, there was a surge of interest in things American?

Similarly, in June 1861 a dealer called Gilbert, of Falmouth, Cornwall, ordered twelve “Garribaldi [sic]” stone jugs. Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807–1882) had conquered Sicily and Naples for the kingdom of Italy in 1860. Hilliard of Wallingford, southeast of Oxford, purchased one ewer “green Scotland”—which appears to be a printed design—and Charles White, of 30 Gloucester Gardens, Bishops Road, Bayswater, London, purchased tableware with “Green Spanish Views.”[38] Consumers obviously were buying the far-off, the exotic, and ceramic choices perhaps reflected an awareness of international events. What can be concluded about the market at which a ceramic piece was aimed based on its decorative motifs? It is clear that the association of particular designs to localized, cultural identities is rarely so straightforward.

In April 1861 Henry Raymond of Yeovil, Somerset, purchased six flown blue measure jugs, costing 1s. 4 1/2d., and four dozen flown teas, seconds, priced at 8s. (The terms flown and flowing occur regularly in the Cork and Edge documentation.) That same year crockery dealer Samuel Davis of Weymouth also purchased fifteen dozen unhandled teas, described as “flown blue basket” costing £2.1.3. In October 1861 Fynn of Bristol purchased from Cork and Edge this small order:

7 1/4 doz Blue mea [measure] jugs dotted 1.12.7 1/2

10 1/2 doz " " " wine 2.7.3

18 tea cups Flown Blue Basket 1. 4. 1/2

4 doz wine measure mugs Blue printed 11.

crate 9.6

£5.1.9

In March 1867 Cork and Edge’s West of England traveler took an order for “3 sets Jugs 12 to 30 Albion F.Blue Singa.”[39] (A mug in this flow blue pattern is illustrated in figure 15.) Even Ferd di Franco, a crockery dealer in Naples, Italy, purchased flown blue sugars and flown blue salads in 1862.[40]

References to flow blue first appeared in the American press and invoices in the early 1840s. In New York in 1844 Davis Collamore advertised “Dinner sets of the ‘Flowing Blue.’”[41] In Albany, McIntosh’s “China Hall” had “Extra rich flowing blue that will match through an entire set of one color—a rare and splendid article.”[42] An 1846 invoice of John Ridgway and Co., Cauldon Works, Shelton, addressed to Adam Southern of Philadelphia, listed table-, tea-, and toilet ware as “FB.”[43] Demand also existed away from the East Coast, as E. Cauldwell of Utica, New York, wrote to John Whiting in January 1846:

The above goods [six W. Granite cover dishes and six W. Granite bakers] were forwarded yesterday, via the Housatonic R.Road. We were unable to furnish you either with the Gold fig. china, or flowing blue tea ware, but shall have a full supply of both for early spring.[44]

Albany’s China Depot offered “FLOWN PLUMB COLOR,” “FLOWED BLUE,” and “FLOWED MULBERRY” tableware in 1851.[45] By way of comparison, in 1861 H. Truby of Bicester, Oxfordshire, purchased “2 [part or pair] Chambers Mulberry & Marble costing 2s 4d.”[46]

Strangely, references to flow-printed wares were ubiquitous in America at this time but were not prevalent in British advertisements. For instance, in the Chester Chronicle of April 1844 “families and parties furnishing” were invited to Dean, Elliott or Lime Streets, Liverpool to purchase “Barnished Gold China tea sets,” “China tea cups and saucers from 1s 6d,” “Jugs and basins stone,” and “stone water jugs.” Liverpool-based outlets often stressed that ceramics were suitable for export, making it hard to determine what might have been for local or for foreign consumption. Nevertheless, the Cork and Edge sales ledger provides an enormous number of crockery dealer locations, making it a valuable tool for unearthing references to Staffordshire goods. One of Cork and Edge’s Scottish customers was Martin Rigney of Kirkcaldy, Fife. In 1849 he purchased goods worth £5.9.8, and in 1850 he advertised, in frustratingly vague terms, a “Cheap Sale Extraordinary of China, Glass, Ironstone, & Earthenware” at his Kirkcaldy china store (fig. 16).[47]

Another Cork and Edge customer in Scotland was Alexander Wilson of Peterhead, located approximately twenty-five miles north of Aberdeen. Wilson appears in the ledgers in 1851 and represents Cork and Edge’s most distant British customer. In the Aberdeen Journal on March 5, 1851, Wilson advertised from his “Staffordshire Warehouse” at Peterhead, requesting hawkers, rag collectors, and rag merchants to supply him with rags of every kind for which he was willing to pay the highest prices.[48] Also in March 1851 he advertised: “The Most Extensive STOCK OF CHINA, GLASS, and EARTHENWARE, both of Foreign and British Manufacture, North of Aberdeen, is to be had at ALEXANDER WILSON’S Wholesale and Retail Glass and China Ware SHOPS, Marischal Street, Peterhead. Staffordshire Warehouse, Peterhead, 19th March, 1851.” When Wilson did provide more information about his ceramic stock it clearly was aimed at the farming sector. In April 1851 he advertised “Wholesale China, Glass, and Earthenware / To Country MERCHANTS / ALEX.WILSON begs to intimate to country merchants / That he has just received a cargo of the best / English Manufactured MILK PLATES and CREAM JARS / Staffordshire Warehouse, / Peterhead, 23rd April, 1851.”

Many of the British advertisements surveyed from the 1840s and early 1850s used vague and generic language, making it hard to determine whether flow blue was commonly used in England at the same time it was used in the United States. Cork and Edge documentation does prove that flow blue was sold to British crockery dealers in the 1860s, and serves to convey a more complete picture of British ceramic consumption than that found in advertisements alone.

There is no basis that flow blue and mulberry were specifically tied to the American market in the first place, unlike white ironstone ware, which was closely linked by contemporaries to the United States.[49] For instance, the Staffordshire Advertiser of 1852 pointed out that there had been “a great change of taste among transatlantic purchasers; white ware of very superior quality taking the place of the printed ware formerly in vogue.”[50] In 1862, during the American Civil War, the Staffordshire press noted that “many factories which made only white ware for the American market have been closed for months,” implying that without American buyers it was of limited use for the British market.[51] John Maddock of Burslem even went so far as to stipulate “We make white granite ware, which is particularly adapted for the American market.”[52] It was these comments, not just the lack of physical evidence in British collections, that reinforced my suspicion of a growing divergence in ceramic demand between the United Kingdom and the United States.[53]

Modern collectors use the term white ironstone to describe a type of earthenware with a molded design rather than printed decoration. To contemporaries this type of ware was often known as white granite. Exactly when this earthenware first appeared in the United States is difficult to determine because ceramic terminology was, and continues to be, so varied. “Granite China” was used as early as 1838, “Granite ware” appeared in 1847, and “white granite” appeared in a New York auction notice of 1849.[54] In January 1846 E. Cauldwell of New York dispatched to John Whiting of Utica “W. Granite” dishes and bakers. A reference to “Ridgway’s Best White Ironstone ware of every description” dates to 1843.[55]

The evidence indicates that in the United States white granite and flow blue existed at the same time, during the 1840s; invoices, advertisements, and British trade reports suggest that by the 1850s white granite ware was the more important commodity.[56] Sales of white granite, according to surviving invoices, began to outweigh the sales of printed or painted wares in the 1850s to 1870s.[57] Reflecting this trend was an 1854 advertisement placed by The China Hall on Broadway, Albany, which stated, “we would particularly call attention to a beautiful assortment of White Ironstone China of extra quality and finish, and entirely new styles” while also mentioning that flowed blue, mulberry, and queensware were available.[58]

References to white granite (or flow blue) in British newspaper advertisements are absent in the mid- to late 1850s, however. The town of Chester, which clearly relied on the Staffordshire Potteries for supplies of ceramics (although by no means all of the stock), began to stress in the Chester Chronicle & Cheshire and North Wales Advertiser that the goods were aimed at local consumption. William Webb of Chester advertised in 1855, “China breakfast and tea services: Enamelled ditto, Ironstone ditto: Earthenware ditto: Dinner services and Toilet sets in endless variety of new patterns and shapes. Agent for the Royal Patriot Jug, a memorial of the present war, and Shakspere jug. Mason’s Ironstone ware, Worcester and Coalport China dinner services & matched. . . .” Webb’s advertisement states that “Royal Patriotic Jug. Messrs Alcock & Co. China Manufacturers, being desirous of putting it within the reach of all to possess a Memorial, both of the present War and of the noble and generous sympathy displayed by all classes have published a Patriotic Jug” (fig. 17).[59] A later ad by Webb invited the “Nobility, Gentry and Inhabitants of Chester and North Wales generally” to his store.[60]

In 1858 John Barber of Chester was selling, among many other articles, “Minton’s productions, Wedgewood Ware, and Ridgway’s elegant designs” (fig. 18), and his ability to supply the top and bottom ends of society is revealed in his reference to selling “the humblest article of Buckley work.”[61] John Barber had, in fact, been a customer of Cork and Edge from 1848 to 1854, proving that connections definitely existed between Chester and a variety of Staffordshire manufacturers.[62] By 1869 William Webb had sold richly gilt china breakfast sets “from the celebrated Worcester and Coalport houses”; richly gilt and enameled ironstone and earthenware dinner services; richly gilt painted groups; enameled “imperial green grounds” in dessert services; and toilet ware in a variety of colors, described as “gilded, enamelled, painted and printed.”[63]

Apparently no white granite was advertised in the Chester press, yet Cork and Edge sent white granite ware in fairly large quantities to Duranty and Company and to Milligan, Evans and Company, both of nearby Liverpool, and to Nichols and Company of London. One example of the wares dispatched to Milligan, Evans and Company was itemized as follows:

April 1st 1858

20% off Flown and coloured £4. 7.10 3/4 is 17s.6 3/4

25% off Printed £8.12.6 3/4 is £2.3.1 3/4

30% off Printed & traced £41.6.9 1/2 is £12.8.0 1/2

35% off Common £60.19.2 1/2 is £21.6.8 3/4

40% off Printed & Flown Paintd £109.9.8E÷$ is £43.16.0

42 1/2% off Granite £34.1.2 1/2 is £14.9.6

Total £187.1.9d.[64]

What was for domestic consumption and what was for export remains difficult to determine.[65] We do know that on October 28, 1861, C. Norris of Worcester purchased from Cork and Edge thirty-six white granite dessert plates for 7s. 6d., and six white granite jugs worth 1s. 10d.—a good example of white granite being sold well away from the coast, implying British consumption.[66]

References to white granite were not uncommon in the orders that Cork and Edge received from British crockery dealers. J. Walters of Chepstow, Monmouthshire, purchased two white granite covered soups and trays for 3s. 8d.; the rest of the order was for printed and dipped wares amounting to £4.17.7.[67] Wrenford and Company of Torquay, Devon, purchased nine dozen white granite “daisy muffins” for 9s. 6d., with the rest of the order consisting of printed table- and teaware, and CC kitchen- and toilet ware totaling £7.0.7 3/4.[68] Cork and Edge dispatched to Henry Raymond of Yeovil, Somerset, “6 tall candlesticks 8 in[ch] Stanley W. Granite” (8d. each), costing 4s. With this new information, my basic premise expressed in “‘Supplying the Present Wants of Our Yankee Cousins...’”—that American ceramic demand significantly diverged from that of the British by the mid-nineteenth century—is somewhat undermined.

Mocha and dipped wares in the United States have been represented as the cheapest available decorated hollow wares, a commodity associated with the American market by scholars but not thought to be imported in any quantity after the 1840s.[69] A survey by K.A.G. Raybould, published in 1984, drew attention to how commonplace mocha ware was in Britain, although he struggled to definitively date some of the extant pieces.[70]

The Cork and Edge archival material shows that in 1861 Buckley and Son of Poole, Dorset, purchased two dozen mocha jugs and printed tableware, as well as china tea cups, breakfast plates, and bread and butter plates. (The china had been acquired by Cork and Edge from Minton and Company.[71]) Crockery dealer Thompson of Oxford purchased a huge quantity (forty-seven dozen) of plain drab mocha mugs for £3.18.4, and two dozen dipped mugs for 3s. 4d.[72] On November 20, 1861, Philips of London was sent nine dozen mocha mugs costing 15s. The demand for mocha was geographically widespread and in the 1860s the ware was still relatively inexpensive: two dozen “CC jugs” cost 5s.; two dozen “moca jugs” cost 6s.; two dozen “blue check’d jugs” cost 9s; and six dozen “moca mugs” and six dozen “dpt mugs” cost 10s.[73] Correspondingly, two dozen “dpt [dipped] bowls” cost 4s. 6d., and two dozen “CC bowls” cost 4s.[74] Only CC ware was cheaper than mocha or dipped ware.

In Raybould’s 1984 survey he refers to the use of mocha in pubs, which is confirmed in the Cork and Edge records. An 1861 order from Williams of Bristol was for 27 1/2 dozen mocha mugs, priced at £2.19.7, that were marked “I. Pring Three Horse Shoes. Old Market House.”[75] Having goods marked made them slightly more expensive. When Williams of Bristol ordered another twenty-eight dozen mocha mugs in the same period, unmarked, the cost was £2.6.8. The July 1866 order of Miss Humphries of Chippenham, Wiltshire—“3 Mugs Plain Drab mark’d ‘Dumb Post Inn’ (you have the plates)”— also indicates the intended use of the items.[76]

The most common complaint that Cork and Edge received from retailers was that it supplied incorrect sizes. Frequent references are made to mugs or jugs (often with mocha decoration) being “Exact” or “Exact or no use.” What was meant by this is made clearer when Messrs Buckley and Son of Poole ordered eight dozen mocha jugs but stipulated that these must be “Exact—or no use. The jugs 12" held over a noggin—out of 48, 6 only exact.”[77] The reference to the forty-eight jugs being mostly inexact was to the wares sent to Buckley in a previous order. A noggin is a small quantity of spirits, usually equivalent to a quarter of a pint, and was a term used in retailers’ orders.[78] As it has already been established that mocha mugs were ordered with the name of inns or pubs on them, the demand for exact mocha mugs or jugs would be consistent with landlords serving drinks of specific volume.[79] The evidence for mocha or dipped wares being used in pubs rather than the domestic sphere is strong by this period.[80] Ceramics fulfilled many different functions within society, and the fact that there were substantial orders for inexpensive mocha in places such as Oxford does not indicate a low status but rather the presence of numerous pubs.

Differing Demand?

It now seems increasingly unreasonable to argue that any specific type of ware was exported to only one particular market. It is feasible that even the most blatantly adapted wares—those with printed American imagery—were at certain times passed off on the British market. So where does this leave the notion of diverging demand? A more modified view would be that the differences that existed between Britain and the United States had more to do with the volume of the wares being sold, rather than with their type.

In order to explore this hypothesis, a series of comparisons were made. Appendixes 1–6 compare wares sold by Cork and Edge with invoices sold by American crockery importers on the East Coast. Appendixes 1 and 2 contrast the wares sold in July 1860 by Cork and Edge to Lewis of Wantage, near Oxford, with the wares sold in November 1860 by Seymour, a New York crockery importer, to Lee and Dickson, an American retailer.[81] A downside of this comparison is the obvious discrepancy in the size of the two orders, which might easily distort a sense of proportions. However, if orders to Cork and Edge of a greater value are selected, they are invariably from dealers based in Liverpool, London, or Manchester, which brings us back to the problem of goods being potentially for export.

Nevertheless, the comparison presented in Appendixes 1 and 2 reflects activity before the American Civil War. At the start of the war, Staffordshire ceramic trade with the United States temporarily collapsed.[82] Cork and Edge had United States and North American customers (fig. 11), and there is the possibility that wares regularly shipped to the United States simply remained on British soil during periods of trading slumps.[83] This would not have been the case in 1860.

There are similarities between the American and British orders. Edged wares were 6 percent of the value of the British order, and 6.7 percent of the American. However, printed wares were present in Britain but not in the American invoice. At least $123.87 worth of the American invoice (which totaled $231.53) was for white granite, equivalent to 53.5 percent. Only 4.5 percent of the total value of the British sale was described as white granite.

Appendixes 3 and 4 concern the wares dispatched in July 1860 by Cork and Edge to E. Dukes of Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, compared with an invoice from D. B. Stedman and Company of Boston dated November 1860. D. B. Stedman and Company, importers of crockery and china ware, were, according to this invoice, “Agents for J. W. Pankhurst, S. Bridgwood & Sons, Mayer & Elliot and George Wooliscroft,” all of Staffordshire. Typical of East Coast importers’ invoices to retailers is the fact that the actual manufacturer of the goods is not stipulated. The total of the Stedman invoice was, before the discount, $85.60, of which $60.93 (or 71 percent) was white granite. Duke ordered decorated and printed wares but no white granite, dipped (“dpt”), or edged wares. The only similarity in this comparison is the reference to what appears to be Rockingham ware, which represents 1.6 percent of the American invoice and 5.8 percent of the British one.

In Appendixes 5 and 6, an order of April 20, 1866, from Miss M. A. Blanton of Newnham, Gloucestershire, to Cork and Edge is compared with an invoice dated May 17, 1865, of Stedman and Company, Boston. The Cork and Edge order lacks prices but is used in this case to highlight differences in ceramic proportions. A large quantity of the Stedman invoice was for white granite (“20 1/4 dozen and 26 setts”), compared with Blanton’s order, which was for twenty-eight dozen printed willow. Clearly, there was a strong distinction between demand for printed ware in Britain and the demand for undecorated earthenware in the United States. However, Blanton did order four dozen muffins and six jugs, described as “P. White,” likely a reference to Pearl white ware.[84] Ironically, flow wares are referred to in Blanton’s order to Cork and Edge. Flow printed wares were still in demand in Britain.[85] In contrast, the demand for flow ware in the United States had declined enormously in the 1860s.[86]

What do the comparisons in Appendixes 1 to 6 actually prove? If anything, that more data must be gathered, and it is my hope that this paper will be the starting point for compiling greater information. The survival of orders in Britain emphasizes how difficult it is to convey a picture of Anglo-American demand without making sweeping generalizations. In one instance, on August 31, 1866, Otis Norcross of Boston ordered from Cork and Edge five hogsheads of ware, each containing:

30 dozen alphabet Bord[er] col[ore]d plates

10 dozen Fancy Cans

5 dozen Grounded mugs

5 dozen No. 2 drab mugs.

4 dozen Gold lustre teapots ribb[e]d not painted.

30 Toy tea sets Pink . . . [illegible].[87]

These were just the sorts of wares that Cork and Edge supplied to the home market. Therefore, information from both sides of the Atlantic needs to be combined if a more detailed picture of demand is ever to emerge.

Economic and Social Factors

If it is assumed that a notion of diverging Anglo-American demand is down to the proportions of wares consumed, rather than types, why did these proportions vary in the first place? Why would certain types of wares be more popular in one country than in another, or the same ware popular in countries at different times? On the face of it, an explanation could be due to the confluence of economic and social factors.

In theory, there should be a relationship between ceramic consumption and spending power, but caution has to be exercised as to how this can be measured. For instance, in October 1846 John Ridgway and Company, Shelton, sold to Adam Southern of Philadelphia:

10 dozen London teas unhandled “FB” [flow blue] £2.10s

10 dozen London teas unhandled “Painted 2nds” 8s 4d[88]

As the painted teas were seconds, a meaningful comparison is hard to make, but it was not the cheapest decorated ware available, even with the additional deduction of 25 percent off the flow blue given on this invoice.

In a Charles Meigh of Hanley invoice of May 1847 addressed to E. E. Smith, Philadelphia, there is a reference to “10 dozen Verona teas unhandled/ “Flown Athens” / £2.10s.[89] The whole invoice was for “Flown” table-, tea-, and toilet ware, and in this case 20 percent was discounted with an additional, unexplained 5 percent off part of the order. Already it is clear that prices for the same types of ceramics were unstable in a relatively short period of time. Not only did the price of flow blue printed vary, but it was priced differently compared with other printed wares. On January 19, 1847, T. J. and J. Mayer of Stoke sold to Van Heusen and Charles of Albany, New York:

10 dozen teas “Albut” unhandled “Flowed Blue Ambesque” £2.10s

30 teapots 24s “Washn Flowed Blue Ambesque” £1.10s

30 teapots 24s “Washn Grecian Scroll dark blue” £1.10s[90]

Mayer deducted 35 percent off the “dark blue” and 25 percent off “Flowed blue.” More of this invoice relates to flow blue printed rather than dark blue printed, meaning that there were plenty of printed and painted wares cheaper than flow blue, casting doubt on a suggestion that flow blue only sold well because it was inexpensive.

Did white granite—undecorated earthenware—sell only because it was inexpensive? In 1858 Titus Hammersley of Stoke exported to George Hammersley in Philadelphia:

6 dozen unhandled London teas “Pearl White Granite Atlantic” £1.10s

16 dozen unhandled teas “neat painted” £1.16s

16 dozen unhandled teas “blue Dipt” £1.16s[91]

Hammersley’s deductions of 42 1/2 percent off white granite, making the six dozen teas 17s. 3d., and 35 percent off both “neat painted” and dipped, making them 9s. 7d. for six dozen, clearly demonstrate the higher price of white granite compared with other wares.

The Titus Hammersley invoice to George Hammersley dated October 18, 1858, also shows that twenty dozen dishes “Pearl White Granite Atlantic” cost £16.7s. (not including the 42 1/2 percent discount), while 160 dozen dishes “willow” only cost a mere £2.16.6 (again without the 35 percent discount). Another comparison indicates that ten dozen “Pearl White Granite Atlantic” bakers cost £4.18, whereas two hundred dozen “willow” bakers cost a mere £2.3.4. In these instances it was much cheaper to have decorated “willow” ware rather than white granite in the United States.

However, it does depend on which printed wares are compared with white granite. An invoice of T. Furnival of Cobridge, to P. Wright, Philadelphia, April 14, 1869, records:

20 dozen unhandled London Teas “White granite Union” £5.0.0

30 dozen unhandled London Teas “Flow Blue Avon” £7.10.0[92]

Initially it appears that flow and white granite were the same price (working out at 5s. per dozen), but at the end of the invoice there was a 42 1/2 percent discount given on “White granite” and 32 1/2 percent given on “Flown printed.” White granite was in this instance cheaper than printed ware, but it must be stressed that of the £224.8.7 net value, only £15 of it was flow blue, the rest was white granite. The switch from printed to white granite was so extreme in the United States that it is hard to make comparisons concerning price within the same invoices.[93] White granite could be more expensive than some printed wares, but CC ware was still the cheapest.[94] The value of white granite declined in the second half of the nineteenth century, but only slightly.[95]

If there were straightforward economic explanations for ceramic consumption, an interpretation of ceramic demand would be relatively easy, but the above conveys the complexity of the situation. Added to this was the flexibility of price that occurs in some instances, and in the case of Cork and Edge the pricing strategy seems completely erratic. On July 15, 1861, a buyer called Bowers of Dartmouth, Devon, was sold

2 dozen willow deep bakers at 12s. 9d.

On October 10, 1861, Wrenford and Co., of Torquay, Devon, was sold

3 dozen willow bakers 10s 6d.

Two weeks later, on October 26, 1861, Williams of Coleraine, Londonderry, Northern Ireland, was sold

2 dozen willow deep bakers at 7s. 9d.

whereas the same day Williams of Coleraine, Londonderry, was sold

3 dozen willow bakers at 13s. 6d.

If the difference is due to the quality of the printed willow ware being firsts or seconds it is certainly not referred to as such in the Cork and Edge’s account book.

Was there a possibility of prices being adjusted to reflect an ability to pay? The traveler writing to Cork and Edge of Humpries based at Chippenham, Wiltshire, recorded “Miss Humphries Toilet sets 5/4 [5s. 4d.] she never gives more and buys from E. J. Ridgway & others.” Perhaps this implies that an increase in price would result in the loss of a customer; thus prices were managed accordingly.[96] Cork and Edge varied credit, which might, in turn, have affected a retailer’s prices to the actual consumer. In April 1866 John Bryant of Stroud paid cash in one month,[97] yet Richard Southwood, St. Thomas of Exeter, was allowed to pay cash after two months.[98]

Writing some years before Veblen’s Theory of the Leisure Class, M. L. Arnoux, art director of Minton and Company, assumed that a form of emulation was the cause of a demand for white granite in the United States: “white granite, made for the American market . . . is richly glazed, and made thick to compete with the French hard porcelain, which is also exported to the United States for the same class of customers.”[99]

It is not currently fashionable for design historians to support “emulation theory,” perhaps with good reason—as an all-encompassing theory it does not explain all aspects of consumption, and, at the same time, it assumes a great deal about motivation and awareness of the alternatives available.[100] But since Arnoux makes a connection between French china creating a demand for white molded-decorated English earthenware, this point is worth exploring. As Arnoux stated that white granite was aimed at the same class of customer as French china, this is more akin to Pierre Bourdieu’s model of consumption, with emulation more likely to occur within the same social stratum.[101] The price differential between French china and white granite makes Arnoux’s observations hard to envisage. In an 1868 invoice of Howland and Jones, Boston, twenty dozen club-handled coffees, described as “French china extra thick Hotel ware,” cost a staggering $80.00. On the same invoice five dozen white granite coffees heavy cost $8.75. In other words, twenty dozen white granite coffees still would have cost only $35.00.[102]

French china certainly was exported in large quantities to the United States.[103] Britain, by contrast imported only £4,814 worth of French china in 1860.[104] However, as it has been shown that white granite was being sold (by Cork and Edge, at least) to British consumers, this would surely run counter to the emulation theory. It is also true that American crockery importers marketed white granite as an alternative to French china, and on some occasions it was described as suitable for steamboats and hotels. Conversely, the amount of French china imported into Britain in 1880 reached £105,269.[105] If emulation was the reason for the rise of white granite in the United States, why does the same pattern not emerge in Britain? There are problems with attributing the rise of certain goods to emulation and yet, if it is dismissed entirely as an explanation, it still remains a problem to satisfactorily understand why the demand for white granite in the United States seemingly outweighed the consumption of white granite in Britain.

Networks

Perhaps to really get close to understanding why differences and similarities existed in Anglo-American demand, a much greater knowledge is required of the networks of trade, the role of retailers, and even how ceramics were viewed by consumers. As the Pottery Gazette succinctly put it in 1896:

the shopkeeper has the advantage over the manufacturer in that he can watch the inclinations of the public taste, and is thus able to meet it. Sometimes that taste can be led, and occasionally it can even be diverted from a line it was evidently taking, but very frequently, far more frequently than some manufacturers are aware of, the prevailing taste of the public must be judiciously met.[106]

Travelers were obviously useful at making contacts. Larkinson of Biggleswade, near Cambridge, wrote to Cork and Edge, “your traveller was at my house last week and he said that we could have as many as we thought proper we give him an order for 50 D (dozen).”[107] On occasion Cork and Edge’s West Country traveler (J. G. Hawley of Bristol) was sent samples.[108] On November 23, 1866, Hawley sent orders from Gillingham, Dorset. By November 30 orders arrived from Bristol, and between January 7 and 9, 1867, he was in Neath, South Wales, sending a total batch of orders from Newport, Aberdare, and Merthyr.[109] Cork and Edge used the railways to supply the retailers, and the normal procedure was for the crockery dealer to return the empty crates (certainly when dealing in the United Kingdom) when placing the next order.[110]

Through distribution networks crockery dealers might copy the types of wares seen in the stock of neighboring crockery dealers. Charles Smith of the “Wholesale & Retail Glass & China Warehouse, 72, St. Mary’s Street, Weymouth,” wrote to Cork and Edge requesting blue-printed dinner ware Mezieres pattern, “such as you were in the habit of sending S. Davis. You can hear of me at Wedgwoods, Mintons, E. J. Ridgways, Davenports, B’Westheads, T. & A. Green & Co. Fenton, Meir & Co., Hammersley & Co. &c &c W. T. Copelands.”[111] Samuel Davis was also a Weymouth crockery dealer who appeared in a Cork and Edge sales ledger in 1857, and who had bought jugs described as Weymouth views in 1861.[112] This is a hint of how particular goods became known and desirable (even though Charles Smith dealt with many other manufacturers). Some of Smith’s demand came from the network of trade routes that existed, and it is known that dealers traveled from their stores to increase the sale of their goods.[113] Had Cork and Edge not sold to Samuel Davis in the first place, would Charles Smith have desired the same pattern? This is a form of emulation, but not an instance of Charles Smith going to London to learn about current “fashion” and this trickling down to the provinces. Demand could, perhaps, be far more localized.

By the same token, demand is reflected in the links made by crockery dealers if they visited the Potteries. In 1866 David J. Greenshields wrote from Montreal:

You were kind enough to say in reply to an enquiry from me a year or so ago when in England, that you would supply me with the “Blue Marino” ware such as Mr. Godwin (with whom we had an account) used to make. I therefor [sic] beg to annex a small order.[114]

Adapting Goods

John Styles suggests that design historians have not readily explored how information about changes in fashion and design were communicated back to the manufacturer. This was especially necessary if, as Styles argues, there was a geographical separation between manufacturer and consumer.[115] This is a valid point, and apparently, even when there was not much of a geographical separation, information was still required. For example, when Thomas P. Burton of St. Austell, Cornwall, placed an order with Cork and Edge for ninety dozen teas Ceylon dark purple printed, six dozen Chambers CC and six dozen Chambers sponged, on November 9, 1866, the traveler’s letter referred to: “T. P. Burton wants you to make a little stronger purple. When it gets a little extra glaze it looks weak. I hope you will give him your best attention.”[116] Therefore, there was an expectation that retailers could adapt goods. Presumably, the crockery dealers felt that changes would improve sales, and the fact that the traveler passed on the comment infers that manufacturers were amenable to requests. So, within a manufacturer’s evolving customer distribution there existed dealers apparently capable of exerting change to the goods—yet another factor to take into account when attempting to explain differences in demand.

The Buyers and Attitudes to Goods

It has been established that many crockery retailers were women; even if a man’s business was not described in his wife’s name, she still had considerable influence over it.[117] Women were traditionally perceived as the housekeepers, and the Cork and Edge material seems to support their pivotal role as consumers of crockery.[118] When the agent of Cork and Edge took a crockery order from Halshaw of Brigg, south of Hull, he noted: “[Halshaw] Grumbled very much as the very little attention he has had this time. He has 2 ladies coming daily about the dinner sets you have on order. So make an effort to send them at once.” Further down the order is the reference to:

1 Trent E [ewer] & Basins Albion

1 " Soap

1 " Brush

1 " Sponge

A lady has bought this set and waits the above additions—make every effort to send them.[119]

The above reaffirms the role of women selecting and adding wares of the same set, as might be anticipated. But what did the goods actually mean to buyers? On one occasion Hawley wrote to Cork and Edge that “R. Hill [Bristol] finds great difficulty in getting rid of the seconds with so little flat [plates] in the crate.” Hawley continued, “could you please pack him a/c at once a crate as early as you can to underneath order any pattern, pheasants, cottage or willow but not higher,” which clearly establishes how designs were rated.[120] These comments parallel the findings on invoices—that old patterns were priced differently from newer ones.

Printed willow tableware occurs in many orders sent to, and dispatched by, Cork and Edge in the 1860s.[121] Curiously, it was slightly more expensive in Britain than it was in the United States. For instance, according to its Day Book, Cork and Edge sold to Bowers of Dartmouth, Devon, twelve willow covered dishes at 9s. in 1861. In 1858 Titus Hammersley sold to George Hammersley in Philadelphia twelve willow covered dishes at 13s., with a 35 percent discount, which equals 8s. 5 3/4d. Cork and Edge even sold Lloyd of Leamington Spa, Warwickshire, twelve willow “covd [covered] dishes 10 in[ch]” at 10s. on April 17, 1861.

Is it possible that demand influenced prices? As shown above, an 1858 invoice of Titus Hammersley of Stoke to George Hammersley of Philadelphia had willow ware at considerably lower prices than white granite, but the demand for printed wares in the United States was in decline in the second half of the nineteenth century.[122] George Lewis of Wantage, near Oxford, bought his “White granite Daisy Plates” for 11d. per dozen, whereas a dozen of his “willow plates” were purchased for 1s 1 3/4d. (see Appendix 1).[123] In terms of price, this was the complete reverse of what was happening in the United States.

Different zones of consumption were recognized and a thorough knowledge of this would be useful. When Charles Fowler of Calne, east of Bath, ordered “Teas Bute, drab & white inside,” from Cork and Edge, the traveler stressed: “not seconds teas to be sent in cold [colored, most likely] bodies, people buying this class of article will not have inferior goods.”[124] This suggests that for those able to buy the more expensive types of goods, only perfect ones were acceptable, indicating more than just a desire for a particular ceramic design, but that a sense of quality and of display was important. If customers were prepared to spend on expensive goods, this suggests an element of snobbery and is evidence of ceramics acquiring a social meaning. Overall, however, the above points are just tantalizing glimpses of how trade networks, retailers, and buyers could have an impact on demand. Examining ceramic consumption from the perspective of the consumer may well provide the insights that are still desperately required to account for differences in Anglo-American ceramic demand.

Conclusion

The Cork and Edge information highlights that advertising in newspapers (particularly in Britain) does not always convey what was actually being sold. With more data from invoices and orders it might be possible to define more accurately the differences in the ceramic proportions that apparently existed between Britain and the United States.

If this paper does convey an accurate portrayal of aspects of Anglo-American demand, why is it that wares such as flow blue and white granite are not significantly represented in British ceramic collections and museums? The Cork and Edge material proves that these wares were consumed in Britain. In a final twist to an already complex story, American scholar Arnold Kowalsky sadly died in February 2005, having spent the last thirty-five years researching and collecting ceramics. His obituary recorded how “he bought and sold flow blue; importing large quantities of the ‘blue’ from England—one of the first dealers to do so.”[125] It is my belief that certain types of wares were originally exported in large quantities to the United States, and collectors have inevitably picked up on their own distinctive material culture. They collected what was available to them and then acquired ceramics from elsewhere. It is very feasible that collecting has gradually distorted, even perhaps accentuated, the differences that we see. Nowadays, the danger of taking too literally what exists in collections and museums is that it does not always allow for the point at which different ceramics types became collectible and worthy of preservation. If the physical evidence is perhaps distorted, then this can only be addressed by continuing to search for more documentary and archaeological evidence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am extremely indebted to Dr. David Barker for reading and commenting on this paper, and for providing key photographic images.

Good examples would be George Miller, “George M. Coates, Pottery Merchant of Philadelphia, 1817–1831,” Winterthur Portfolio 19, no. 1 (spring 1984): 37–49, or George L. Miller, Ann Smart Martin, and Nancy S. Dickinson, “Changing Consumption Patterns: English Ceramics and the American Market from 1770 to 1840,” in Everyday Life in the Early Republic, edited by Catherine E. Hutchins (Winterthur, Del.: Winterthur Museum, 1994), pp. 219–48.

Arnold R. Mountford, “Thomas Wedgwood, John Wedgwood and Jonah Malkin: Analysis of Certain Unpublished 18th Century Documentary Sources with Particular Reference to the Manufacturer and Distribution of Earthenware and Stoneware” (master’s thesis, Keele University, Keele, Staffordshire, 1972), vol. 2, Table F, pp. 114–21. The names of London and provincial dealers supplied by the Wedgwood brothers are given circa 1750–1770. Alternatively, Sheenah Smith, “Norwich China Dealers of the Mid-Eighteenth Century,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 9, pt. 2 (1974): 193–211.

Jill Turnbull, “Staffordshire Potters and Scottish Merchants,” Journal of the Northern Ceramic Society 9 (1992): 115–22, provides a source of customer distribution in the early nineteenth century. Keith Matthews, “Familiarity and Contempt: The Archaeology of the ‘Modern,’” in The Familiar Past? Archaeologies of Later Historical Britain, edited by Sarah Tarlow and Susie West (London: Routledge, 1999), pp. 155–79, has used ceramic sherd evidence to convey aspects of consumption in the Victorian slum dwellings of Chester, England.

Neil Ewins, “‘Supplying the Present Wants of Our Yankee Cousins...’: Staffordshire Ceramics and the American Market 1775–1880,” Journal of Ceramic History 15 (1997): 1–154.

Miranda Goodby, keeper of ceramics at The Potteries Museum, Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent, has acquired printed flow blue and mulberry and white ironstone wares from the United States, to address gaps in the collection. The Museum of Sunderland has on display a small number of flow blue and one piece of undecorated white ironstone dated to the mid-nineteenth century.

Maureen Batkin, Wedgwood Ceramics, 1846–1959: A New Appraisal (London: Richard Dennis, 1982), particularly “The Introduction: Wedgwood in the 19th and 20th Centuries,” discusses the employment of French designer Emile Lessore (1805–1876), and the opening of a new London showroom in 1875. See also Joan Jones, Minton: The First Two Hundred Years of Design and Production (Shrewsbury, Eng.: Swan Hill Press, 1993), especially chap. 7, entitled “Pâte-sur-Pâte,” and the role of French designer Louis Marc Solon (1835–1913).

Denis Stuart, ed., People of the Potteries: A Dictionary of Local Biography (Keele, Eng.: Department of Adult Education, University of Keele, 1985), vol. 1. Apparently, the Cork and Edge partnership ran from 1846 to 1860, becoming Cork, Edge and Malkin (1860–1870), then Edge, Malkin and Company (1870–1902). An article entitled “Buyers’ Notes” in the Pottery Gazette (December 1899), p. 1421, however, described Messrs. Edge, Malkin and Company as being founded in 1815. For simplification, this firm will be referred to as “Cork and Edge” throughout this article.

Cork and Edge ledger, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, PA/W-N/8 (hereafter PA/W-N/8).

Cork and Edge ledger, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, PA/W-N/25 (hereafter PA/W-N/25). For instance, Antonio Patty (also spelled Pattey) Naples was sent fifty dozen CC plates, CC tureens and salads, white plates, willow ware and Toy teas (July 28, 1863).

Cork and Edge Day Book, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, PA/W-N/24 (hereafter PA/W-N/24).

Cork, Edge and Malkin Correspondence, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, 738.94246 (hereafter Correspondence).

Minutes of Evidence on the Wellington, Drayton and Newcastle Junction Railway Bill, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, May 8–16, 1862. Ridgway employed 400–500 people in 1862. Minutes of Evidence and Speeches of Counsel on Potteries Junction Railway Bill, Stafford Record Office, D4842/16/2/53, April 29, 1863. Minton and Company employed 1,500 people in 1863. Census, 1861; Joseph Edge (of Cork and Edge) stated that he employed 133 men, 94 women, 66 boys, and 32 girls. Judging by the figures supplied by other Staffordshire manufacturers, Cork and Edge was a medium-size factory. In 1861 Elijah Hughes, earthenware manufacturer in Cobridge, employed 200 people, whereas James MacIntyre, a manufacturer in Burslem, employed 111 people. John Maddock of Burslem employed 200 people according to Minutes of Evidence and Speeches of Counsel on Potteries Junction Railway Bill, April 29, 1863.

Census, 1861; for the numbers employed by Enoch Wedgwood. Enoch Wedgwood and Company signed price-fixing agreements for those involved in the American market in the 1870s. See Ewins, “‘Supplying the Present Wants of Our Yankee Cousins...,’” p. 16. Nevertheless, in J. G. Harrod and Co.’s Postal and Commercial Directory of Staffordshire (1870), Wedgwood and Company was described as earthenware manufacturers for “Home, American and Continental markets.”

Correspondence, Doc. 212, July 27, 1867. Matilda Whittle requested the name of china manufacturers that Cork and Edge would recommend.

PA/W-N/8. Copeland was sent goods in 1849 worth £10.10.7, and was supplied in 1851, 1855, 1858, and 1860. Minton and Company was supplied goods worth 2s. 2d. in 1850 and 16s. 4d. in 1851. Goods continued to be supplied in 1852, 1854, 1855, 1856, and 1857.

In the Pottery Gazette, silk, brass, and copper lawns were frequently advertised. They were used to sieve materials.

This information was gleaned from the surviving 1863–1867 correspondence of Cork, Edge and Malkin.

Lorna Weatherill, The Pottery Trade and North Staffordshire 1660–1760 (Manchester, Eng.: Manchester University Press, 1971), pp. 81–83. The 1754–1760 sales of John Wedgwood were chiefly to London.

Neil McKendrick, “Josiah Wedgwood: An Eighteenth-Century Entrepreneur in Salesmanship and Marketing Techniques,” Economic History Review, n.s. 12, no. 3 (1960): 414, 420–22.

Correspondence, Doc. 117, April 10, 1867. Letter from Jno Edwards, Liverpool, mentions goods being bought on account of Huntington and Brooks of Cincinnati.

Llewellynn Jewitt, The Ceramic Art of Great Britain from Pre-Historic Times down to the Present Day: Being a History of the Ancient and Modern Pottery and Porcelain Works of the Kingdom and of Their Productions of Every Class, 2 vols. (London: Virtue and Co., 1878), 2: 259. Jewitt mentions and illustrates two teapots and a jug exhibited in 1851. R. K. Henrywood, Relief-Moulded Jugs, 1820–1900 ([Woodbridge, Suffolk]: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1984), pp. 194–95. A page from the “Paris Universal Exhibition Catalogue” is illustrated, showing a selection of Cork and Edge molded ewers with titles such as “Vine,” “Lily,” and “Grape Gatherer.”

Mountford,“Thomas Wedgwood, John Wedgwood and Jonah Malkin,” pp. 114–21. The Wedgwoods supplied customers throughout England from circa 1750 to 1770 but did not directly supply European customers.

Correspondence, Doc. 91, January 8, 1867. J. Van Hees was listed in Het Algemeen Adresboek van Amsterdam, 1856–1857, at Korte Nieuwendijk, l53, as a dealer in Porcelein en Engelsch Aardwerk. I am grateful to Dr. J. Boomgaard, director of Amsterdam Municipal Archives, for providing this information.

Gore’s Directory of Liverpool (1787) lists Ann Salters, earthenware dealer, John Street, Liverpool, and Mary Wood, dealer in earthenware, Old Hall Street, Liverpool.

Jane Rendall, Women in an Industrializing Society: England, 1750–1880 (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1990), esp. chap. 2, “Women, the Family and Economic Change 1750–1830.” By an occasional correspondent, “The Lady of the China Shop,” Pottery Gazette (May 1905): 546–47. This article praised the leading role played by women in the selling (and buying) of ceramics, suggesting that they possessed good taste and were able to move deftly around the shop, and so forth.

Gore’s Directory of Liverpool (1853) lists Elizabeth Dunbar as a china and earthenware dealer. In 1865 it lists Isabella Dunbar, 190 Park Road, Liverpool, as a ceramic dealer.

Daniel Lawrence of Grafton Street, Dublin, placed orders with Cork and Edge from 1849 to 1853, followed by Jane Lawrence from 1854 to 1855. Alexander Thom, Thom’s Irish Almanac and Official Directory for the Year 1856 (Dublin: A. Thom, 1856), lists Mrs. Lawrence, 2 Nassau Street, Dublin. In Alexander Thom, Thom’s Irish Almanac and Official Directory for the Year 1857 (Dublin: A. Thom, 1857), Mrs. Lawrence was described as running a “China, glass and delph warehouse” at the same address.

In William Mathew’s Bristol Directory (1860, 1865), J. G. Hawley was listed as a commercial traveler and agent. In 1860 his address was 3 Lawrence Place, Bristol. Correspondence, Doc. 48, September 8, 1866.

Ewins, “‘Supplying the Present Wants of Our Yankee Cousins...,’” pp. 28–31. Wedgwood wares were advertised in the New York press.

PA/W-N/24, November 1861. Addressed to A. B. White Esq., 83 Inverness Terrace, Kensington Gardens, London, the order included “72 plates 10 inch, with crest arm holding wreath in proper colours & motto in gold on turq. & gold.”

Correspondence, Doc. 120, April 12, 1867. Memorandum and reply on reverse.

J. G. Harrod and Co., Royal County Directory of Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Berkshire, and Oxfordshire (Norwich: Royal County Directory Offices, 1876). George Lewis was listed as having a “china and glass warehouse, a good assortment of toys and fancy goods,” Newbury Street, Wantage. According to this directory (p. 539), Wantage had a population of 9,265.

PA/W-N/24, September 8, 1860.

Correspondence, Doc. 53, July 19, 1866. Kelly’s Directory of Hampshire, Wiltshire, Dorsetshire and the Isle of Wight (London: Kelly’s Directories, 1867). In 1861 Chippenham, thirteen miles northeast of Bath, had a population of 5,396.

Correspondence, Doc. 22, April 15, 1865. Order from J. Goods[?] Jr., 19, High Street, Hull, requested the name of “Brough Chapel” within an oval, to be placed on white and gold tea and tableware. A drawing was supplied to convey the request clearly.

PA/W-N/24, October 30, 1861.

Correspondence, Doc. 111, March 21, 1867. An order from Buckley and Son, Poole, Dorset, requested 34 dozen plates, 2 cheese stands, 26 dishes, 2 soups in what was termed “Blue American.” It is debatable whether this meant American views.

PA/W-N/24, December 6, 1861.

Correspondence, Doc. 111, March 21, 1867. Order from George Etheridge, Ringwood, Hampshire.

PA/W-N/25.

New York Commercial Advertiser, September 16, 1844.

Albany Evening Journal, May 15, 1845.

Warshaw Collection of Business Americana, Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., Box 3, October 31, 1846 (hereafter Warshaw).

Warshaw, Box 1, letter dated January 2, 1846. A John Whiting was listed in the Utica City Directory (1847–1848) as a wholesale and retail dealer in china, glass, and earthenware.

Albany Evening Journal, July 2, 1851.

American and Commercial Advertiser, March 28, 1855. George Herring advertised “250 crates White Granite ware, 250 crates Common, 30 crates Printed, 30 crates Marbled.”

Fifeshire Advertiser, May 18, 1850.

“A .W. will be also glad to hear from parties having from five to fifty tons of Rags on hand, for which a high price will be given—cash.” Henry Mayhew, London Labour and the London Poor, 4 vols. (1861–1862; unabridged reprint, New York: Dover Publications, 1968), 1: 365–70, describes crockery street sellers exchanging goods for old clothes.

John Dimmock and Company of Hanley claimed in 1880s advertisements placed in the Pottery Gazette to be the “Originators” of flow blue, but it was not linked by them to any particular market.

Staffordshire Advertiser, November 20, 1852.

Staffordshire Sentinel, June 14, 1862.

Minutes of Evidence and Speeches of Counsel on Potteries Junction Railway Bill, Stafford Record Office, D4842/16/2/53, April 29, 1863.

Expressed in Ewins, “‘Supplying the Present Wants of Our Yankee Cousins....’”

Albany Evening Journal, August 9, 1838 (McIntosh’s Ceramic Store); Albany Evening Journal, January 4, 1847 (Gregory and Company); New York Commercial Advertiser, October 2, 1849 (Corlies, Haydock and Company).

North American and Daily Advertiser, Philadelphia, March 31, 1843 (Tyndale’s Store).

Ewins, “‘Supplying the Present Wants of Our Yankee Cousins...,’” pp. 44–46, app. 5, 6.

Ibid., app. 6.

Albany Evening Journal, July 5, 1854 (Tucker, Crawford and Rector).

Chester Chronicle, April 28, 1855.

Chester Chronicle, November 24, 1855.

Buckley, Flintshire produced utilitarian articles in slip and coarse ware; Mary Wondrausch, Mary Wondrausch on Slipware: A Potter’s Approach (London: A. and C. Black, 1986), pp. 65–66.

PA/W-N/8. Only values are given in this ledger rather than details of the actual wares.

Chester Chronicle, January 9, 1869.

Correspondence, Doc. 269, letter dated September 11, 1867, from Milligan, Evans and Company, Liverpool, to Cork, Edge and Malkin.

Correspondence, Doc. 65, September 24, 1866. An order from Scrutton Sons and Company, 3 Corbet Court, Gracechurch, London, included a memorandum that states that the ordered earthenware was intended for Dominica West Indies.

PA/W-N/24, October 28, 1861. See also Littlebury, Directory of the City of Worcester, July 1869 (London, 1869), which lists “Coningsby Norris, china, glass and earthenware warehouse, gilder and enameller, 55 Tything Street.”

PA/W-N/24, October 28, 1861.

PA/W-N/24, October 10, 1861.

Jonathan Rickard, “Mocha Ware: Slip-Decorated Refined Earthenware,” Antiques 144, no. 2 (August 1993): 185–87.

K.A.G. Raybould, “Some Aspects of Mocha Ware,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 12, pt. 1 (1984): 41–44.

PA/W-N/24, August 12, 1861.

PA/W-N/24, November 18, 1861.

PA/W-N/24, J. Rowe, Pontepool, March 14, 1861; ibid.; PA/W-N/24, E. Dukes, Aylesbury, July 3, 1860; PA/W-N/24, H. Raymond, Yeovil, May 23, 1861; Lloyd, Leamington Spa, April 17, 1861.

PA/W-N/24, Mrs.Williams, Coleraine, October 26, 1861.

According to Webster and Company’s Directory of Bristol and Glamorganshire (1865), a James Pring was the publican of Three Horse Shoes, 70 Old Market Street, Bristol.

Post Office Directory of Wiltshire (1859) lists “Dumb Post,” run by W. Palmer, Bremhill, Chippenham.

Correspondence, Doc. 81, November 21, 1866.

Correspondence, Doc. 102, March 12, 1867. When Josiah Hayward of Wells ordered two dozen porter mugs he required “1/2 pint and noggin.”

Correspondence, Doc. 82, November 22, 1866. Mr. E. Jackson, Ilminster, ordered four dozen mugs, 6- and 12-inch “Exact Blue Dipt.”

Raybould, “Some Aspects of Mocha Ware.”

The buyer is given as Lee and Dickson but their location is not given.

Staffordshire Sentinel, January 14, 1865. A trade article estimated that 95,460 packages of earthenware exported from Liverpool to the six principal American ports in 1860 had been reduced to just 29,754 in 1861.

Chester Chronicle, January 4, 1879. An advertisement of Webb, Howarth and Company, “Have just purchased, at considerable Reduction in prices, in consequence of the great depression in the trade in the Potteries, a large stock of Goods.” Apparently, china breakfast services cost 21s., dinner services cost 18s. 6d., dessert services cost 25s., china tea services cost 11s. 6d., and chamber services cost 6s. 8d. Retailers and consumers benefited from depressions.

Correspondence, Doc. 274, September 13, 1867. “P. White” seems to be Pearl White, and pearl white was undecorated. W. R. Jeffrey, Saffron Waldon, wrote, “I intended the pearl white jugs to have been plain as described in my order of 24th ult.”

Correspondence, Doc. 123, April 13, 1867. Letter and order from H. Raymond, Yeovil, referred to “F. Blue Mugs, 12, 2 Handles.”

Warshaw, Box 7, April 14, 1869. Invoice of T. Furnival, Cobridge, addressed to P. Wright, Philadelphia, totaled £224.8.7, with only £15 of this amount described as “F. Blue Avon” muffins and unhandled London teas; the rest of the invoice was for white granite.

Correspondence, Doc. 151, August 31, 1866.

Warshaw, Box 3, October 31, 1846.

Warshaw, Box 3, May 3, 1847.

Warshaw, Box 3, January 19, 1847.

Warshaw, Box 6, October 18, 1858.

Warshaw, Box 7, April 14, 1869.

Ewins, “‘Supplying the Present Wants of Our Yankee Cousins...,’” app. 5.

Warshaw, Box 6, March 31, 1871. Invoice of Clementson Brothers, Hanley, addressed to W. Kline and Company, Philadelphia. Twelve dozen London unhandled teas described as “St. Louis” white granite cost £3 (5s. per dozen), whereas sixty dozen London unhandled teas Tulip CC cost £6 (2s. per dozen). Even though Clementson deducted a discount of 45 percent off Granite and 35 percent off Common, Common (CC) was still the cheapest.

Warshaw, Box 6, October 18, 1858. Invoice of Titus Hammersley, Stoke-on-Trent. Six dozen unhandled London teas of Pearl White Granite “Atlantic” cost £1.10s. with a 42 1/2 percent discount, making 17s. 3d. for six dozen; one dozen equaled 2s. 10d. Warshaw, Box 7, October 6, 1870. Invoice of Pankhurst, Hanley, to P. Wright, Philadelphia. Ten dozen white granite unhandled London teas “St. Denis” were priced as £2.10s., with a 45 percent discount; one dozen now equaled 2s. 9d. This comparison conveys the slight deduction in the price of white granite.

Correspondence, Doc. 175, July 10, 1867.

Correspondence, Doc. 44, April 18, 1866.

Correspondence, Doc. 51, January 13, 1866.

Thorstein Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study of Institutions (1899; reprint, London: George Allen and Unwin, 1925). G[eorge P.] Bevan, British Manufacturing Industries (London: Edward Stanford, 1877).

Amanda Vickery, “Women and the World of Goods: A Lancashire Consumer and Her Possessions, 1751–81,” in Consumption and the World of Goods, edited by John Brewer and Roy Porter (London: Routledge, 1993), pp. 274–301. Vickery provides a clear assessment of the limitations of emulation theory.

Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, translated by Richard Nice (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1984).

Winterthur Museum Archive, Doc. 74x18, June 6, 1868. An invoice of Howland and Jones, Boston, to Ramsay and Wheeler (location not given).

William P. Blake, “Home Consumption and Import Statements,” in Ceramic Art: A Report on Pottery, Porcelain, Tiles, Terra-cotta and Brick, with a Table of Marks and Monograms (New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1875).

National Archives (formerly Public Record Office), Cust. 5, vol. 62. Britain in total imported £8,667 worth of “Chinaware and porcelain, Ornamented and plain” in 1860.

National Archives, Cust. 5, vol. 123, 1880.

Anonymous, “Retail Business: A Model Provincial China Shop,” Pottery Gazette, August 1896, p. 607.

Correspondence, Doc. 326, ca. 1860.

PA/W-N/24, October 11, 1861. The wares sent to Fynn of Bristol included “samples for Jno. Hawley.”

Correspondence, Doc. 92, January 7–9, 1867. In this instance the orders consisted of some “seconds” luster, blue and green printed tableware, willow tableware, metal covered stoneware jugs and teapots, Rockingham teapots, and some ewers and basins.

Correspondence, Doc. 48, September 8, 1866. Letter from Hawley, Bristol, to Cork and Edge: “Joseph Capus has sent his crate I have promised you should write him to say if rec’d and when order will be ready . . . .” See also Correspondence, Doc. 213, July 26, 1867. A letter from Thomas Smith, Malborough, Wiltshire, states that “Mr.Hawley was hear [sic] on the 10 and promised to send the crate of goods away not later then [sic] the 13 and I have just been to the station and they have no tidings of it and I have sent the invoice back to you as I can do without the crate of goods now as I was obliged to bye[sic] the goods for the purpose that I wanted . . . .”

Correspondence, Doc. 121, April 12, 1867.

PA/W-N/25.

Anonymous, “Trade,” Pottery Gazette, May 1896, p. 365, describes Dukes of Aylesbury, Fawn of Horsham, Wood of Brighton, and Attwood of Exeter as large dealers who apparently visited villages in their own areas to sell goods, although this working practice was considered to be on the decline. Apparently, the general visit had nearly collapsed as most towns and villages had their own shops.

Correspondence, Doc. 36, February 16, 1866. Arnold A. Kowalsky and Dorothy E. Kowalsky, Encyclopaedia of Marks on American, English, and European Earthenware, Ironstone, Stoneware, 1780–1980: Makers, Marks, and Patterns in Blue and White, Historic Blue, Flow Blue, Mulberry, Romantic Transferware, Tea Leaf, and White Ironstone (Atglen, Pa.: Schiffer, 1999), pp. 163, 181, 203, indicates that Thomas Godwin’s engravings (manufacturer, Burslem) were acquired by Cork and Edge.

John Styles, “Manufacturing, Consumption and Design in Eighteenth-Century England,” in Consumption and the World of Goods, edited by John Brewer and Roy Porter (London: Routledge, 1993), pp. 527–54.

Correspondence, Doc. 75, November 9, 1866. Letter and order from J. G. Hawley, traveler.

Correspondence, Doc. 308, ca. 1860, collection of orders, p. 13. It was recorded at the bottom of an order taken by a Cork and Edge traveler that “Mrs Hindle wants me to give her compliments to Mr. Edge and thinks she is entitled to a present of a toilet set after her long dealing.” James Hindle of Accrington, north Manchester, earthenware dealer, purchased goods from 1855 to 1857, according to the Cork and Edge sales ledgers, but this letter uses the phrase “her long dealing.” Kelly, Lancashire Trade Directory (1858), also only lists the business under the name of James Hindle. According to the 1861 Census, James Hindle, Glass and China Dealer, was 38 years old, and his wife, Mary, was 46; both were born in Accrington.

Family Economist: A Penny Monthly Magazine, Devoted to the Moral, Physical, and Domestic Improvement of the Industrious Classes, 6 vols. (London: Groombridge and Sons, 1853), 6: 245–48. An article entitled “Household Economy” describes a family headed by Lydia and Charles Worth: Lydia was depicted as keeping the house clean and tidy, making clothes for her husband and children, and a “good market-woman.”

Correspondence, Doc. 308, ca. 1860.

Correspondence, Doc. 94, January 22, 1867.

Correspondence, Doc. 81–84, November 1866. Orders from Dorchester, Ringwood, Ilminster, Taunton, Chard, etc.

Ewins, “‘Supplying the Present Wants of Our Yankee Cousins...,’” app. 5, 6.

There is insufficient information about the size of the white granite “Daisy plates” to help explain the price difference.

Correspondence, Doc. 175, July 10, 1867.

Obituary by Ellen Hill, ed., in Blueberry Notes, January–February 2005, 4.