Jug, Yorkshire, England, ca. 1830. Stoneware. H. 20". (Noël Hume Collection; photos, Gavin Ashworth, unless otherwise noted.) The exterior of this massive jug is coated with a lustrous red-brown glaze and decorated with multiple sprigs that include portrait busts of William IV (r. 1830–1837) and Queen Adelaide. The interior is coated with an olive-green lead glaze.

Detail of the jug illustrated in fig. 1: portraits of William IV and Queen Adelaide.

Detail of the jug illustrated in fig. 1: the Stag Kill (W. 5"). The motif is paralleled on a pitcher attributed to Brampton in Derbyshire.

Detail of the jug illustrated in fig. 1: the sloppily applied Hanoverian royal arms and their smug but not too bright flanking lions. Note that the separately sprigged device below the arms has been applied off center.

Detail of the jug illustrated in fig. 1: the dolphin-spearing cherub (H. 4") and, to its right, the erasing and trimming away of another part of the mold’s design.

Detail of the jug illustrated in fig. 1: an unidentified “classical” sprig (W. 4 1/4"), which, having been applied too dry, cracked in firing.

Detail of the jug illustrated in fig. 1: the Parson, with his pipe but without his friends (H. 3 1/8").

Jug, Staffordshire, ca. 1790–1805. Pearlware. H. 8 1/4". (Noël Hume Collection.) This press-molded pearlware jug shows the Parson and the Sexton.

Detail of the jug illustrated in fig. 1: a hunter scene (W. 5 1/4"), in which a man or boy, surrounded by hunting dogs, shows a hare or rabbit to his companion.

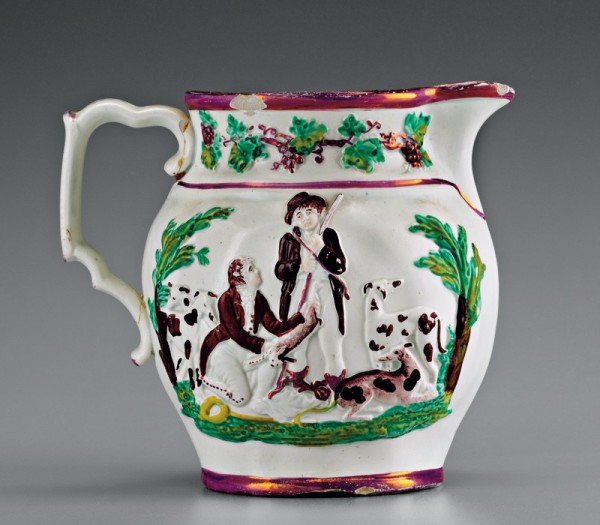

Jug, probably Staffordshire, ca. 1810. Pearlware. H. 6". (Noël Hume Collection.) The hunter scene depicted on this press-molded pearlware jug is decorated in “Pratt” colors. The object in the foreground (unidentifiable on the jug illustrated in fig. 1) might be a dead goose.

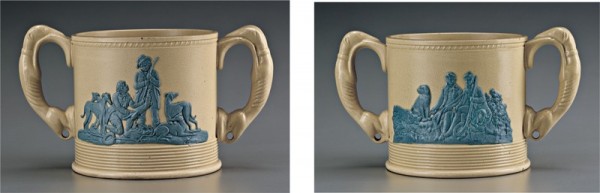

Mug, probably Staffordshire, ca. 1825. Yellow ware. H. 5 3/4". (Noël Hume Collection.) The sprigging on this double hound-handled mug was done with particular care. At left is the hunter scene; at right, shooters at rest with their bag and their dog. Both scenes as stoneware sprigs are present on the giant Eccleshill jug illustrated in fig. 15.

Mug, Derbyshire, ca. 1835. H. 5 1/4". (Noël Hume Collection.) The Fox Kill on this hound-handled mug is the first of a four-sprig frieze.

Detail of the jug illustrated in fig. 1: the dismounted horsemen (W. of each 3 3/4") flanking the Stag Kill scene.

Pitcher, probably Brampton, ca. 1835–1840. Stoneware. H. 15 5/8". (Courtesy, Nicholas Johnson Collection.) The Stag Kill and dismounted huntsmen sprigs on this brown stoneware pitcher parallel those on the jug illustrated in fig. 1. Note the faux screws on both handle and spout.

Jug, attributed to Eccleshill, ca. 1840–1845. H. 24". (Courtesy, Keighley Museum.) A lustrous brown exterior salt glaze and interior olive-green lead glaze cover this giant, which is decorated with portraits of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert as well as the royal arms and hunting scenes. The handle has faux screws at the top and bottom.

Shop jar, Yorkshire, ca. 1840–1850. H. 11 1/2". Pitcher, probably Derbyshire, ca. 1835–1845. H. 5 1/4”. (Noël Hume Collection.) The shop jar, at left, has a pebbled dark brown glaze and is decorated with the Hanoverian royal arms, lions, and topers similar to those on the giant Eccleshill jug illustrated in fig. 15. The pint pitcher, at right, has a lustrous brown upper dip over a drab, unglazed lower body, its sprigs characterized by incised outlining. It has similar albeit larger topers, including the Sexton, who also appears in the pearlware jug illustrated in fig. 8.

Detail of the jug illustrated in fig. 1, showing the handle with its faux screws and lightly scored lateral straps.

What follows is the anatomy of a single salt-glazed stoneware jug, presented in the hope that the steps taken and the disparate clues pursued to catalog it can, themselves, be of interest to readers of ceramic detective stories.

This journal’s title is a mantle to drape a multitude of unexpected treasures, not the least of them a gem that turned up in a Houston thrift shop that specializes in used cowboy boots. As the vendor remembered, it had been brought in by an anonymous bag lady. Nobody thought to ask where she got it or how she managed to haul through the city a jug twenty inches tall and weighing twenty-three pounds. Bought by a Houston collector of Mexican folk art with no abiding interest in stoneware, it was eventually sent to the well-known Slotkin auction house in Georgia, which specializes in modern popular art.[1] Although the auctioneers did not know of the jug’s importance, they thought it sufficiently big and busy to illustrate it in the Maine Antiques Digest, where my wife saw it (fig. 1).

The jug’s significance rests on its portrait busts of England’s King William IV and his wife, Adelaide, who succeeded George IV in 1830 and reigned until 1837 (fig. 2). The presence of the royal portraits around the jug’s neck suggests that the vessel was made to commemorate William’s coronation, thereby providing dating for the several applied devices decorating the body. Readers of previous issues of Ceramics in America might recall my earlier studies of British nineteenth-century brown stonewares and their applied decoration known to potters as sprigs.[2]

The sprigging technique can be traced back at least to the beginning of the Roman Empire. In the late fifteenth century it became popular on German stonewares and would become so in England after 1670, when John Dwight of Fulham perfected the stoneware art. Once established, sprig work flourished through the eighteenth century, decorating large tavern mugs with mounted huntsmen, their hounds, and their prey. Those so-called hunting mugs gave way in the early nineteenth century to jugs portraying more complex sporting themes—depicting hunters on foot presenting game to their master, or watching hounds in the act of the kill. The latter commonly featured a fox or a hare and, occasionally, a stag, as is the case on the massive William IV jug (fig. 3).

As a coronation jug (or so I thought), its principal feature is the Hanoverian version of the British royal arms below a grapevine garland flanked by a pair of lions passant and regardant (fig. 4).[3] Beyond these stands a male figure wearing a well-curled wig and formal clothes of about 1800. He holds a tobacco pipe in his right hand and gestures with his left. At this point the decorator’s design symmetry seemed to desert him, prompting him (or was it her?) to reach for the largest mold on the bench—a winged cherub riding a disgruntled dolphin while thrusting an arrow into its rump (fig. 5).[4] Flanking it are two conventional trees and, beyond them, a pair of dismounted horsemen.

Left to last (because I have no idea what it means) is one more sprig, twice repeated, depicting a pair of putti holding a naked man who they are trying to make read from a large book. Peering out from under the right cherub’s cloak is an animal that resembles a sick dog under a blanket (fig. 6).

So where was this monster jug made, and for what purpose? It is heavy to carry empty and too heavy when four-gallons full. Several such jugs exist, among them the one made by John Bacon for Maria Roberts at the Barrel Inn, Bagworth, suggesting that some were made to decorate the taprooms of rural inns.[5] Their size endows them with what I have long called the “keep me factor,” meaning that they have some attribute that kept them from being discarded during that protracted and perilous period in which they were old but not antique.

We knew (or thought we knew) the approximate age of this jug, but it was the problem of divining where it was made that had us reaching for Sherlock Holmes’s violin and syringes. The clues abound, but where do they lead? To pursue them we have to track down other brown stonewares of more conventional shapes and sizes that have matching sprigged decoration. Thousands have survived either as tavern mugs or kitchen pitchers, usually sprig-decorated in one or a combination of three basic themes: hunting, drinking, and farming. A fourth borrows from designs favored by the upmarket factories of Wedgwood, Turner, Minton, and others catering to the literate classes whose taste turned to the neoclassical at the close of the eighteenth century. Indeed, a social historian might usefully devote years to studying which decoration appealed to what levels of nineteenth-century society. It is unlikely, however, that pothouse spriggers gave much thought to such issues.

A prolonged study by several stoneware collectors has led to the conclusion that a master mold-maker, probably in Staffordshire, supplied “knock-off” copies of quality designs to smaller factories throughout the region. New short-lived plaster molds were impressed from the original matrix, then used to make later-generation positive images with which to make yet more molds. Each step shrank the size and blurred the details, making it impossible to accurately trace a mold design from one factory to another—though I have wasted a great deal of time trying.

There are, nonetheless, some basic narrowing clues. The so-called Toby figure with his table and beer was the premier sprig in the London area (Lambeth, Vauxhall, Fulham, and Mortlake) throughout the nineteenth century, whereas in the Midlands and North of England the designs were more diverse—as the Houston jug demonstrates.[6] Take, for example, the standing man with his tobacco pipe (fig. 7). He had arrived at the jug from an earlier and familiar source: three separate men usually shown together (the Parson, the Clerk, the Sexton). The Parson and the Sexton appear in polychrome splendor on a press-molded Staffordshire pearlware jug of about 1790–1805 (fig. 8), proving that the design had been in use for perhaps thirty years before reaching the Houston jug.

The previously mentioned hunting scene in which one man offers a killed hare (or rabbit) to a colleague is another design that originated in Staffordshire in the early years of the nineteenth century (fig. 9). As a rule it was paired with one showing two bird hunters with their bag and their dogs. My press-molded polychrome pearlware example dates circa 1810 (fig. 10).[7] About ten years later another Staffordshire example of this pairing was blue-sprigged onto a hound-handled mug in a lead-glazed yellow ware and graphically demonstrates the quality to be achieved from a new mold and careful application—in marked contrast to the coarseness of the Houston sprigs (fig. 11).[8]

The Houston jug’s Stag Kill sprig had also seen better days and had its origin in a frieze of butting elements featuring horsemen and hounds in pursuit of a fox (fig. 12). Again, this was a northern favorite rarely, if ever, used by London potters. The Stag Kill also came as a three-element frieze, being flanked by the dismounted huntsmen seen on the Houston jug (fig. 13). The dismounted huntsmen design is also on a transfer-printed pearlware jug in the Burnap Collection, Kansas City, where it is said to be “after Moorland” and is dated circa 1790.[9] The same series was applied to a brown stoneware mug dated 1840 and attributed to Bristol, as well as to a pitcher in the collection of Dr. Nicholas Johnson (fig. 14) that is identical to another in the Chesterfield Museum, where it is attributed to Brampton or to Chesterfield itself.[10] Either would put the place of manufacture in Derbyshire. The question, therefore, is whether by extension we should attribute the Houston jug to Brampton. The answer is “not necessarily.”

In the Keighley Museum in Yorkshire there is an even larger jug whose lower body shape resembles that of the Houston jug and whose sprigged decoration is attributed to circa 1840–1845 (fig. 15). The jug is labeled as having been made in the Yorkshire village of Eccleshill, north of Bradford, and so provides an anchor for the study of comparable Yorkshire stonewares.[11] In the same museum is a quart mug decorated with the Parson and his friends, green-glazed inside and also attributed either to Eccleshill# or farther south to Wibsey.[12] Whereas the latter pottery is known to have been in operation as early as 1763, Eccleshill, according to Oswald, did not start until 1837, making it too late to have made a William IV coronation jug. However, the Keighley Museum label puts the factory’s commencement date less precisely—“about 1835–1837”—and thereby within the reign of William IV. Although the Houston jug is well, even majestically, potted, as I have already noted the sprigs are not sharp and the molds evidently old. One might argue, therefore, that although the royal portraits might have been made at the time of the coronation, they continued to be available for use throughout the reign.

So what of Wibsey?[13] In their seminal book English Brown Stoneware, 1670–1900, Adrian Oswald and Robin Hildyard point out that Wibsey’s “Nineteenth-century wares are thick and heavy with a matt chocolate brown glaze . . . are often sprigged . . . and sometimes [possess] an interior glaze grey-green in colour.”[14] The authors then muddy their puddle by adding “like some Brampton wares.”# They also reference an April 1927 Connoisseur article devoted to Wibsey that illustrated waster fragments found on the pottery site. Those of us unable to put our fingers on the article might assume that the wasters included examples of pertinent sprigs and the telltale green glaze. Alas, they did not.[15]

Oswald and Hildyard also said of Eccleshill that the style of its brown stonewares has “little to discern that is different from the Derbyshire productions.” Nevertheless, they illustrated a brown stoneware jug with the distinctive interior green glaze and inscribed NOTTINGHAM REVIEW OFFICE 1828. And it, too, is sprig-decorated with the Parson and his friends, and is cautiously attributed as “possibly Yorkshire.”[16] Why, one might ask, would a Yorkshire pottery be making a jug for a customer in Nottingham, where brown stoneware had been famous for a hundred years and more? The likely explanation is that although a few potters were working there as late as the mid-nineteenth century, by about 1800 the brown stoneware manufacturing trade had shifted northward to Derbyshire and Yorkshire.

In Derbyshire the earliest use of the dubious “Yorkshire” interior green glaze occurs on a loving cup inscribed “G.H. Nov. 28th 1825,” attributed to Brampton. There were, however, at least nine family-owned potteries making stoneware in or near Brampton, rendering the town name a generic term for the products of that Derbyshire area. That being so, can we use Eccleshill as a blanket name for wares resembling the Houston jug? A later shop jar bought in California fits the category, having the internal green glaze and decorated on the body with similar “toper” sprigs to those ringing the neck of the Keighley Museum’s massive Eccleshill jug of circa 1840–1850 (fig. 16).[17] Those sprigs evidently owe their origin to others commonly used on London wares though differing in details.[18]

Adrian Oswald once told me that an individual potter could be identified from an object’s rims and handles. No doubt there is truth in this when studying the work of art potters who worked alone, but in factories with a large output, the handles, like the sprigs, were made and attached by specialists. About 1805 someone in Fulham decided that if wooden handles had to be secured with screws, faux screws would add an interesting detail to stoneware jug handles. A Lambeth designer went one better, decreeing that, for added “security,” a fake strap should span the handle terminal and be held in place by two screws, a conceit that continued to be used by Doulton into the twentieth century.[19] By the 1830s the screwed handle had gravitated north to Derbyshire and thence (one presumes) to Yorkshire, where it somewhat hesitantly appeared on the Houston jug. Two screws secure the top of the handle and three at the tail, but the lateral straps are suggested only by horizontal scored lines rather than being applied in relief. Unsure how to treat the third terminal screw, the handler chose to score an oval around it, perhaps to replicate a washer (fig. 17). In neighboring Staffordshire, the handle of John Bacon’s 1849 farm jug also has the five screws, albeit without the scoring.[20] The Eccleshill giant, however, has three screws at the top, only two at the decorated tail, and lacks the scored straps. One wonders why—another decorator? Another factory?

The truth, alas, is that Holmesian acumen notwithstanding, the clues, unless documented, can be wildly misleading. Most of what we “know” is based on the fallible opinions of previous writers, curators, and collectors who, if asked why, would reply, “Because I think so.” Inadequate though that is, it also has to be my response to nailing (or screwing) down the bag lady’s big jug. Yorkshire it must be. Eccleshill it may be—if only because I say so.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author is indebted to Richard Fluhr of Houston for finding the jug and deciding to sell it, and to Philip Mernick in London and Nicholas Johnson in Brookline, Massachusetts, for their valued advice as well as the use of their photographs.

Bought by Richard Fluhr of Houston, Texas, who gladly shared with me all that he knew about his purchase.

Ivor Noël Hume, “A-Hunting We Will Go! from Vauxhall to Lambeth, 1700–1956,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. 179–245. Sprigs are relief decoration derived from individual molds and applied to a vessel while in the leather hard state.

The obsolete Hanoverian arms continued to be used well into the reign of Queen Victoria by potters unaware of or not caring that the new queen had not inherited the German crown.

This rather unpleasant scene was evidently extracted from a larger mold.

Ivor Noël Hume, “John Bacon: Prince of Stoneware Potters?” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2005), pp. 20–36.

Noël Hume, “A-Hunting We Will Go!” p. 224.

In Browne Muggs Robin Hildyard states that the “standing topers seem peculiar to Yorkshire stonewares.” Browne Muggs: English Brown Stoneware, exh. cat. (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1985), p. 120, fig. 352. The origin, though not the date, of my Pratt Ware jug remains in doubt, matching fragments having been found on kiln sites as far apart as Bovey Tracy in Devonshire and at the Delftfield Pottery in Scotland. John Lewis and Griselda Lewis, Pratt Ware: English and Scottish Relief Decorated and Underglaze Coloured Earthenware, 1780–1840 (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1984), pp. 106–7, 118–19.

Adrian Oswald, Robin Hildyard, and R. G. Hughes, English Brown Stoneware, 1670–1900 (London: Faber and Faber, 1982), p. 256, state that the hound handles were first used in Derbyshire in 1832. The new generation of hunting designs coincided with the 1792 publication of The Sporting Magazine, which continued under that name until 1831 and whose monthly engravings provided rich fodder.

The dating may be ten years too early, and the association with painter George Morland (1763–1804) is not documented. The jug is illustrated in the 1953 edition of the Burnap Collection catalog as number 588 (p. 97), but was no longer listed when the revised catalog was published in 1967. The same dismounted huntsmen are to be found on a Pratt ware jug attributed to ca. 1800; see Lewis and Lewis, Pratt Ware, p. 174.

Geographic and commercial links to the potteries of the Midlands and the North put Bristol more directly in their design stream than were London’s more conservative decorators. See Hildyard, Browne Muggs, p. 83, no. 214. Nicholas Johnson of Brookline, Massachusetts, is America’s principal authority on English brown stonewares. In England the leading authority is London collector Philip Mernick. Both have valiantly entered the lists to address the challenge posed by the Houston jug. Dr. Johnson’s pitcher is closely paralleled by another dated 1831. See Oswald, Hildyard, and Hughes, English Brown Stoneware, p. 179, fig. 147.

Sprigs on the Eccleshill jug honor the 1840 marriage of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. However, the same portrait sprigs are to be found on a tobacco jar dated 1843 and attributed (rightly, I believe) to Derbyshire. See Oswald, Hildyard, and Hughes, English Brown Stoneware, p. 159, fig. 126b.

Ibid., p. 209, fig. 167 (Eccleshill); Hildyard, Browne Muggs, p. 120, fig. 353 (Wibsey).

Philip Mernick generously shared with me his photographs of Eccleshill wares in Yorkshire’s Keighley Museum as well as those attributed to Brampton in the Chesterfield Museum.

Oswald, Hildyard, and Hughes, English Brown Stoneware, p. 216. They might equally well have said “like some Eccleshill products.” The likelihood that the green interior glaze was a strong Eccleshill pointer was not supported by Oswald, who associated it with Brampton in Derbyshire. Ibid., p. 16.

H. J. M. Maltby, “Wibsey Pottery,” Connoisseur (April 1927): 217–25.

Oswald, Hildyard, and Hughes, English Brown Stoneware, p. 211, fig. 168.

Shop jars are characterized by their straight necks designed to receive a metal (usually tin) lid. A blank ribbon panel was sprigged to the shoulder on which to paste a label identifying the contents. Shop pots, on the other hand, were cylindrical, similarly decorated, and slightly recessed below the lip to seat a metal lid. Sizes range from half pint upward.

Noël Hume, “A-Hunting We Will Go!” p. 235, nos. 1–8.

Fulham shunned the strap but used three screws. Ibid., p. 237, fig. 2. The earliest example had only two deeply inset screws and dated from ca. 1805. Ibid., p. 237, fig. 1.

Noël Hume, “John Bacon,” p. 34, fig. 22.