Roman oil lamp, first or second century a.d. Earthenware. L. 2", H. 1". (Courtesy, APVA Preservation Virginia; photo, Michael Lavin.)

Visitors look on as Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologist Luke Pecararo surveys the initial excavation of the pre-1617 cellar in James Fort that yielded the Roman oil lamp. (Courtesy, APVA Preservation Virginia; photo, Michael Lavin.)

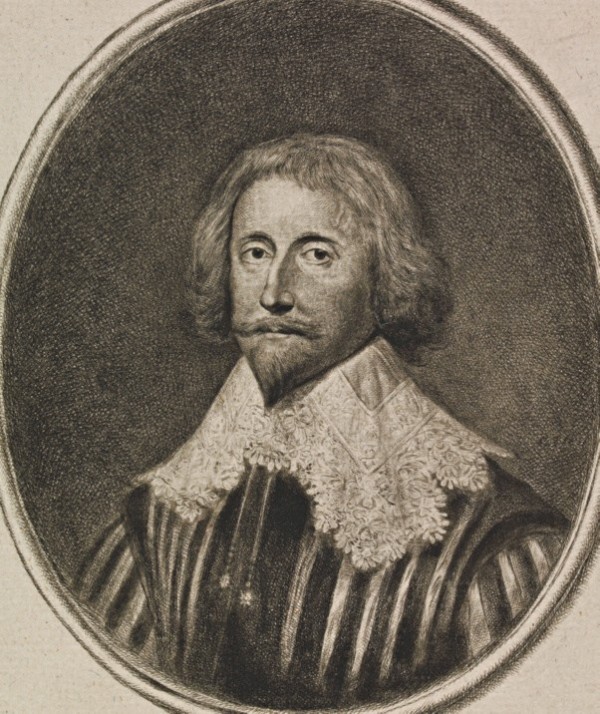

George Sandys, engraving, 1823. (Courtesy, APVA Preservation Virginia; photo, Michael Lavin.) The engraving is based on a 1632 drawing by Cornelius Janssen. Lord Sandys of Ombersley, Worcestershire, owns the original portrait.

The find was astonishing. As the sherds from the unidentified earthenware vessel mended together and the form became clear, it was hard to believe one’s eyes. Taking shape in the Jamestown Rediscovery laboratory was a small Roman oil lamp from the first or second century a.d. (fig. 1)![1] Known as a Firmalampe, or factory lamp, these circular lamps with short nozzles for the wick originated in the Po Valley of Italy. Over a span of four hundred years, large numbers of them were exported to the northern and northwestern provinces of the Roman Empire, where the form was copied.[2] The Jamestown lamp appears to be one of the provincial copies, made in a small workshop in central Gaul, and is a type commonly found in London excavations.[3]

Characteristics of Firmalampen are the “depressed top, two or three raised knobs on the rim, and the factory stamp usually in raised letters on the reverse.”[4] They were produced in two-piece plaster molds, finished by hand, and dipped in an iron slip, which “did not necessarily stop oil seeping through the clay body.”[5] Inexpensive and fueled by vegetable oil, these Roman lamps illuminated the darkness with an efficiency that, according to Donald Bailey, Curator of Greek and Roman Antiquities at the British Museum, was unmatched “until the invention of the circular wick and glass lamp-chimney in the nineteenth century.”[6]

Since archaeologists with the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities began excavations on Jamestown Island in 1994, thousands of ceramic sherds have been uncovered from the site of England’s first successful colony. They are not just English wares but comprise a colorful assemblage from all over Europe and Asia. These international ceramics reflect both the cosmopolitan world of early-seventeenth-century London—the major supply source for the colony—and England’s lack of a substantive ceramic industry at the time.[7]

Some of the ceramics found at Jamestown date to the late sixteenth century. They were made a decade or more before the colonists arrived in 1607 and survived because they were made of durable stoneware, because they were treasured vessels used for status displays, or sometimes because of both. But the Roman oil lamp is the first ceramic finding that is clearly out of context, being almost two thousand years out of its time. It was excavated from the cellar of a building located within James Fort dating to the early seventeenth century. Located close to the “Governor’s Row” of buildings begun by acting governor Thomas Gates in 1611, the cellar had been backfilled by 1617, when it was covered by an addition to the row made by the new governor, Samuel Argall (fig. 2).[8]

How did the Roman oil lamp get to Jamestown and why was it there? Was it scooped up in London with a pile of ballast used to weight ships bound for Virginia? Was it a treasured possession of a colonist who brought it as a remembrance of home? Or, seemingly least plausible, does it indicate the presence of Romans in North America 800 years before Leif Eriksson?

Roman artifacts, particularly coins, are occasionally found in New World contexts and are promoted as evidence of pre-Columbian contact, but usually the finds either cannot be substantiated or are eventually proven to be hoaxes.[9] Even when the objects appear to be valid, like the Roman figurine found in a circa 1476–1510 burial in Mexico, these rare and random finds are not irrefutable proof of a Roman shipwreck or landing.[10] Either scenario would be expected to leave a higher concentration of material near the contact point, not just one or two isolated finds. A logical, and less captivating, reason for these intrusive materials may be that they are purely accidental objects from Roman occupation in an area, such as London, where ballast was collected. This is the accepted explanation for the three small sherds of Roman pottery found on an early-seventeenth-century English shipwreck in Bermuda.[11]

But what if the Roman oil lamp is not a chance find? Could one of the early colonists have brought it to Virginia as a prized personal possession representing antiquity and learning? Were the English already collecting Roman artifacts on their soils in the early seventeenth century? Were they aware of the provenance and date of these ancient objects that turned up in the course of plowing fields or constructing buildings? The theory that a Roman oil lamp was purposely brought to Jamestown by one of the colonists provides an interesting picture of life in James Fort and a better understanding of the individuals who lived there.

The human propensity for collecting objects of interest is an instinct that archaeologist Ivor Noël Hume suggests we share with animal species such as magpies, crows, squirrels, pack rats, dogs, and groundhogs.[12] The human motivation, of course, is not solely about shiny objects or potential food, but is formed by curiosity and a quest for meaning—the lessons of life that can be learned through tangible connections with history. The systematic study and interest in objects from the past is known as antiquarianism and is considered to have originated in England just before the founding of Jamestown.

Most Americans are aware that 2007 marks the four-hundredth anniversary of the founding of Jamestown, Virginia, the first English colony of what would become the British Empire, and where the American form of government and representative democracy first took root. But few know that 2007 is also the tercentenary year of the Society of Antiquaries of London. The “oldest independent Learned Society concerned with the study of the past,”[13] the society was started by three friends gathering in a pub on December 5, 1707, to discuss historical documents and artifacts. Even before this date there was a documented, formalized English interest in antiquities. In the late sixteenth century, a group of primarily aristocratic historians and book collectors formed the Elizabethan College of Antiquaries. These individuals, including Sir Robert Cotton, William Camden, and Sir William Fleetwood, met to discuss subjects of historical importance until King James I disbanded their organization for political reasons. Antiquaries quickly entered the political arena as the material remains of past customs and traditions started being used as historical facts to define the English spirit and to validate the political system. Aware that knowledge was power, the early antiquaries manipulated their understanding of historical texts and artifacts to curry royal favor and support—or just the opposite, if the political climate should change. According to folklorist Roger D. Abrahams, “antiquarianism was one of the primary pursuits of the virtuosi seeking to assert or control power throughout Early Modern Europe.”[14]

The early antiquaries were among the first archaeologists, initially examining relics that were unearthed accidentally during construction projects but soon turning to deliberate excavations to search for artifacts.[15] During his travels through England from 1535 to 1543, for instance, antiquarian John Leland often describes the latest archaeological findings—“pottes exceeding finely nelyd and florishid in the Romanes tymes diggid out of the groundes,” and the “yerthen pott with romoayne coyness” found in Gloucestershire.[16] Historian William Harrison, in his Description of England (1587), often describes the appearance of antiquities, such as this entry for Kingston-upon-Thames in Surrey County: “for in earring [plowing ] of the ground about that town in time past and now of late (besides the curious foundation of many goodly buildings that have been ripped up by plows, and divers coins of brass, silver, and gold with Roman letters in painted pots found there).”[17]

Who were these early antiquarians so interested in digging up England’s Roman past, and could one of them have come to Virginia with a centuries-old oil lamp carefully packed in his chest of belongings? The answer to the second part of that question is a surprising “Yes.” Many of the men coming to Jamestown in the early seventeenth century were the “poet-antiquarian-adventurers, virtuosi, figures who recognized the relationship between knowledge and power.”[18] Among these early adventurers was Edward Fleetwood, younger son of Sir William Fleetwood, previously mentioned as a member of the Elizabethan Society of Antiquaries. Edward Fleetwood died in 1609, either en route to Jamestown or soon after arriving in the colony.[19] His death left his belongings “ownerless” in the colony and, based on surviving records of similar cases, it is likely the objects were placed in the stewardship of the Virginia Council until just compensation was resolved in the London courts. It is very easy to imagine that a Roman oil lamp, representing antiquity and learning to its antiquarian owner, could have been an object of very little value to others in Virginia and discarded with its owner’s death.

Infamous Captain John Smith is another early antiquarian, for even though he was not a gentleman, he was well read and often used classical themes in his writings. As was customary for the time, his English grammar school education included Latin and exposed him to Roman poets, philosophers, and historians such as Ovid, Seneca, and Plutarch. In the words of classical scholar Richard M. Gummere, “Smith . . . was ever a herald of something new, flavoring it with the ancient history which he loved and exemplifying the classical enthusiasms of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.”[20]

William Strachey, who served as secretary of the colony in 1610–1611, is even more representative of the seventeenth-century antiquarian. A graduate of Emmanuel College, Cambridge, and a member of Grays Inn—one of the four Inns of Court training lawyers—Strachey peppered his writings with classical illustrations. One only has to read his A True Reportory (1610) and The Historie of Travaile into Virginia (1612) to appreciate how he “wisely used his Greco-Roman material in its modern application.”[21] For instance, Strachey strongly believed that it was England’s role to spread the Christian religion and to civilize the Virginia Indians, with force if necessary. He supported this with the example of the Romans in Britain, who, through violent means, “reduced the conquered parts of our barbarous island into provinces and established in them colonies of old soldiers, building castles and towns, and in every corner teaching us even to know the powerful discourse of divine reason (which makes us only men and distinguisheth us from beasts).”[22]

Although in Jamestown much too late to be associated with the enigmatic Roman oil lamp, George Sandys is among the most illustrative of these poet-adventurer-antiquarians. Educated at Oxford and son of the archbishop of York, Sandys came to Jamestown in 1621 as the colony’s treasurer and with the intention of completing an English translation of the fifteen books of Ovid’s Metamorphoses (he had already translated five while still in England). As he departed for Virginia, poet Michael Drayton gave him encouragement to “go on with Ovid, as you have begun.”[23] Taking advantage of otherwise unproductive hours, Sandys completed two more books during the voyage “amongst the roreing of the seas, the rustling of the Shrowds, and Clamour of Saylers.”[24] Sandys finished the final eight books of translation during the four years he was in Virginia, 1621–1625 (fig. 3). These were difficult times for the colony, encompassing both the 1622 massacre and the 1624 dissolution of the Virginia Company. The contrast between his hours spent in scholarly pursuit and the reality of life in Virginia prompted Sandys to write that his work was a “double Stranger. Sprung from the Stocke of the ancient Romanes; but bred in the New-World, of the rudenesse whereof it cannot but participate, especially having Warres and Tumults to bring it to light in stead of the Muses.”[25]

To bring Metamorphoses to light, Sandys told his sponsor, King Charles I, that his translations were “limn’d [illuminated] by that unperfect light which was snatcht from the houres of night and repose.”[26] To illuminate his evening hours, Sandys required candles, which were very expensive, or an oil lamp. Only one brass and four ceramic candlesticks have been found in the early James Fort contexts, testifying to the rarity of these objects. Only two early-seventeenth-century Raeren stoneware oil lamps have been excavated from the site. By necessity, most individuals in the colony structured their day based on natural light. Only the gentlemen, such as George Sandys, had the option of using the hours past sundown to do any productive work.

Is it possible that our Roman oil lamp was brought to Jamestown by an antiquarian either to represent antiquity and learning or to illuminate his evening hours? Without written documents supporting this theory, it is difficult to prove. Nevertheless, it is interesting to ponder that we have individuals at James Fort who were considered antiquarians in seventeenth-century English society, and that we have a nearly complete object from an early fort context that would be of extreme interest to an antiquarian.

Postscript: As I was completing this article, several tiny sherds of Samian ware, the mass-produced fine tableware of Roman Britain, were recovered from the same context as the oil lamp. Very fragmentary, they appear to be likely candidates for intrusive ballast fill, and their presence throws the theory of a curated Roman oil lamp at Jamestown into doubt. Was the lamp brought to Jamestown purposely, or was it an accidental hitchhiker with river ballast? We may never know.

Beverly A. Straube, Senior Curator, Jamestown Rediscovery, APVA Preservation Virginia; bly@apva.org

Jamestown Rediscovery is an archaeological research project of the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities (APVA Preservation Virginia) at Historic Jamestowne.

Donald M. Bailey, “Roman Pottery Lamps,” Pottery in the Making, edited by Ian Freestone and David Gaimster (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997), p. 164.

I am grateful to Angela Wardle, Roman pottery finds specialist with the Museum of London, for confirming the identification of the oil lamp.

Oscar Broneer, “A Late Type of Wheel-made Lamps from Corinth,” American Journal of Archaeology 31, no. 3 (July–September 1927): 330. There does not appear to be a mark on the Jamestown lamp, although it might have been obscured by the wear on the base.

Bailey, “Roman Pottery Lamps,” p. 169.

Ibid.

Beverly Straube, “European Ceramics in the New World: The Jamestown Example,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 47–71.

According to the Virginia Company records, when George Yeardley took over as governor in 1619, the traditional residence was a house that Gates had built and that Samuel Argall had enlarged while he was governor (1617–1619). Susan Myra Kingsbury, ed., The Virginia Company Records, 4 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1935), 3: 101–2; The Ancient Planters of Virginia, “A Brief Declaration,” in Jamestown Narratives, edited by Edward Wright Haile (Champlain, Va.: Roundhouse, 1998), p. 907.

Ivor Noël Hume, Here Lies Virginia (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1970), pp. 3–4; Jeremiah F. Epstein, “Pre-Columbian Old World Coins in America: An Examination of the Evidence [and Comments and Reply],” Current Anthropology 21, no. 1 (February 1980): 1–20.

Romeo Hristov and Santiago Genovés, “Mesoamerican Evidence of Pre-Columbian Transoceanic Contacts,” Ancient Mesoamerica 10 (1999): 207–13.

Ivor Noël Hume, Martin’s Hundred (New York: A Delta Book, 1982), pp. 301–2.

Ivor Noël Hume, All the Best Rubbish (New York: Harper and Row, 1974), p. 17.

David Gaimster and Bernard Nurse, “The Society of Antiquaries of London over 300 Years,” British Antique Dealers’ Association Annual Handbook 2007/2008 (London: Burlington Magazine, 2007), p. 4.

Roger D. Abrahams, “Antick Dispositions and the Perilous Politics of Culture: Costume and Culture in Jacobean England and America,” Journal of American Folklore 111, no. 440 (Spring 1998): 115.

Peter Burke, “Images as Evidence in Seventeenth-Century Europe,” Journal of the History of Ideas 64, no. 2 (April 2003): 275.

Lucy Toulmin Smith, ed., The Itinerary of John Leland in or about the Years 1535–1543, 5 vols. (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1964), 4: 131.

William Harrison, The Description of England: The Classic Contemporary Account of Tudor Social Life, edited by Georges Edelen ([1587]; reprint, Washington, D.C.: Folger Shakespeare Library; New York: Dover Publications, 1994), p. 300.

Abrahams, “Antick Dispositions,” p. 117.

Edward Fleetwood’s will was proved in England on December 19, 1609. It states that he departed for Virginia on May 8, 1609. He may have been sailing with Captain Samuel Argall, who left in May 1609 and, sailing the northern route, arrived in Jamestown on July 13, 1609. Argall was back in London by November 9, 1609 (The Will of Edward Fleetwood of London, P.R.O. Ref: PROB 11/114); Philip Barbour, ed., The Complete Works of Captain John Smith, 3 vols. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986), 1: 127–28.

Richard M. Gummere, “The Classics in a Brave New World,” Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 62 (1957): 134.

Ibid., p. 127.

William Strachey, “The History of Travel into Virginia Britannia [1612],” in Jamestown Narratives, p. 588.

Gummere, “Classics in a Brave New World,” p. 125.

Kingsbury, Virginia Company Records, 4: 66.

Richard Beale Davis, “America in George Sandys’ ‘Ovid,’” William and Mary Quarterly 4, no. 3 (July 1947): 298.

Ibid.