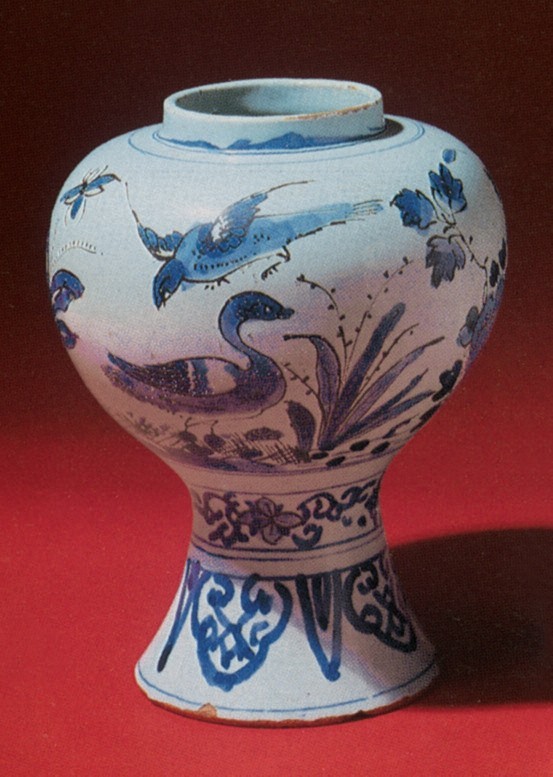

Vase, London or Bristol, 1700–1710. Delftware. H. 6 3/8". (Author’s collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The thrown band and colors appear to be unrecorded for English objects of this type.

Vase, London, ca. 1690. Delftware. H. 5 3/4". (Courtesy, Jonathan Horne.) The vase is decorated in shades of blue within dark manganese line boundaries.

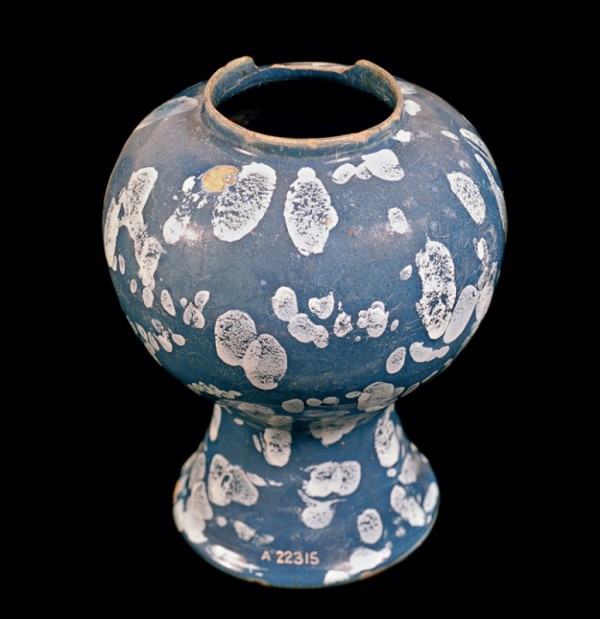

Vase, London, late 17th–early 18th century. Delftware. H. 6 1/4". (Courtesy, Museum of London.) This example has white tin-glaze splotches over a dark blue dipped body.

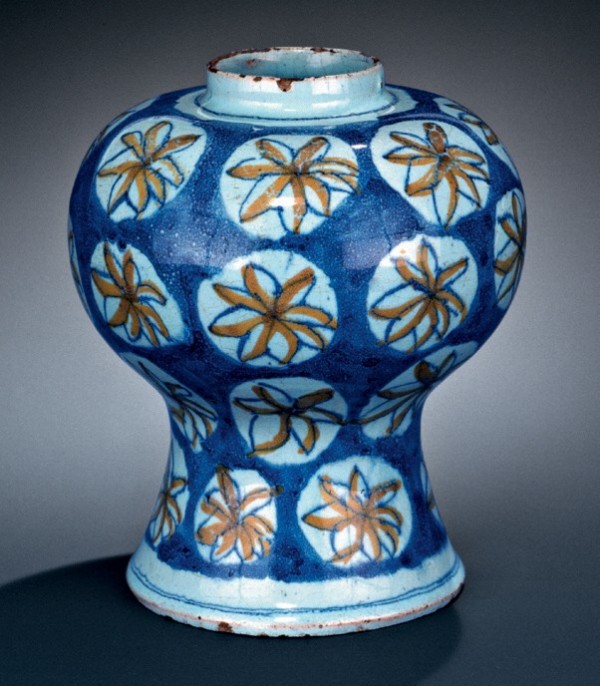

Vase, London, ca. 1690. Delftware. H. 5 1/4". (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) The painted and speckled blue ground of this vase surrounds blue-and-yellow star-shape flowers within clear circles. For a small meiping vase (13.5 cm) with chrysanthemum heads in a white reserve on an underglaze blue background, see Jessica Harrison-Hall, Catalogue of Late Yuan and Ming Ceramics in the British Museum (London: British Museum Press, 2001), fig. 9.40.

An intriguing English delftware vase has been shelved here and there for a number of years, but it has not been presented to observers and researchers in a definitive way. Beyond rarity, it has special merit among its genre companions because of both its profile and coloration. This “delft” is where a biscuit earthen body was given an opaque burnt tin dip that also contained raw glaze ingredients; it was then air dried and decorated in watercolor fashion with glaze-and-color mixed paints before final firing and fusing to set all the colors and glazes. Turned profiles and lively drawings provided the predominant decorations. Gilt and enamel were rarely applied, but many wall tiles in particular were transfer-printed with overglaze during late-production years.

Historically, English gentry, especially, imported elegant showpieces of oversize Chinese porcelain as well as Dutch pottery during the period surrounding the turn of the eighteenth century.[1] The largest ceramics were sought after more in England than Holland.[2] In retrospect this homeland custom was probably supported by the effusive practice of Queen Mary II (r. 1689–1694), who had colored “flower pots” installed such as those found “in ye chimney” at her residence.[3] These could well have been open urns to hold small ornamental trees in fireplaces during the summer. Direct influence came from her palatial surroundings while in Holland for eleven years.[4] Some time ago, the decorating of earlier European chambers with massed ceramics was scholarly interpreted based on an analysis of a 1697 inventory showing the later adoption of similar ostentatious formats at Kensington Palace in London.[5]

In keeping with commercial ventures that correspond to other high-value decorative items being imitated, it is reasonable that nearby pot makers understood the royal vogue and sought their own share of this continuing market for style by courting less affluent yet aspiring clients. Perhaps for practical reasons of manufacture and sale, scaled-down earthenware elements of the likely assembled porcelain garnitures, which often were grouped as three covered jars and two beakers for tall furniture or mantel, became standard forms for the resembling products.[6]

The small early-eighteenth-century delft vase at hand (fig. 1), a probable chimney-shelf component, shows a pointed ovoid baluster shape inverted to that of conventional Chinese porcelain; the highlight is its being thrown with a pronounced swollen girdle. Most likely it originally had a high-dome cover with ball finial on an extended stem. Other English pottery vases of this period also have not retained that probable completeness. The circular base and severely constricted shaft set it apart from Continental comparatives that predominantly have faceted, broader supports.[7]

Further, the inglaze blue-red-green palette featured here seems to be singular among later British as well as its own contemporary English pieces of associated outline, some of which are cited below for comparison.[8] In this primary instance, varied friezes that are separated by assorted line bands include flowerheads and birds amid profuse subsidiary star-bursts and quadruple dots; secondary themes by zone show stylized waves, cloud scrolls with cones, or a stiff pendant lappet-and-leaf chain.

Absent defining hollow ware oven wasters, it becomes necessary to extrapolate from other type sherds, remaining objects, and information sources in order to presume the local origin and date for this vase. Evidence from the popularity of its Chinese-inspired drawing leads to the first decade of the eighteenth century. Intensity of primary colors and their texture as well as handiwork at birds and scales while applying them closely relate it to a covered punch bowl dated 1705, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.[9] The age range seems firm. Whereas I give precedence to London before Bristol in part for more prospective sales from the capital city, there is at present no certain discrimination to choose between these places at the understood time of this piece.

Within this family of effectively multicolored English vase offerings, which total relatively few, can be found such contrasts as classic bird or figural themes (fig. 2), white-splashed bleu persan (fig. 3), and patterns within a reserve ground (fig. 4). Another handful of comparable vases with only shades of blue in white bases also remains.[10]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks are extended to Michael Archer and Jonathan Horne for sharing their thoughts. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Jonathan Horne, and the Museum of London kindly provided photographs.

Troy D. Chappell, Collector

Michael Archer, “Delft at Dyrham,” in National Trust Yearbook 1975–76 (London: Europa Publications for the National Trust, 1976), p. 13.

Michael Archer, “Pyramids and Pagodas for Flowers,” Country Life 159, no. 4099 (January 22, 1976): 169.

Archer, “Delft at Dyrham,” pp. 14–15. Queen Mary II reigned jointly from 1689 to 1694 with King William III of Orange, a great-nephew of King Charles I. She was the eldest and Protestant daughter of King James II of England, Scotland, and Ireland, who reigned 1685–1689. After she died, King William III continued his monarchy until his death, in 1702.

For an overview of her ceramic furnishings and appreciation of them, see A.M.L.E. Erkelens, “Delffs porcelijn” van Koningin Mary II: Ceramiek op Het Loo uit de tijd van Willem III en Mary II / Queen Mary’s “Delft Porcelain”: Ceramics at Het Loo from the Time of William and Mary (Apeldoorn: Het Paleis; Zwolle, The Netherlands: Waanders, 1996).

Linda Rosenfeld Shulsky, “Queen Mary’s Collection of Porcelain and Delft and Its Display at Kensington Palace: Based upon an Analysis of an Inventory Taken in 1697,” American Ceramic Circle Journal 7 (1989): 51–74.

Robin Reilly, Wedgwood: The New Illustrated Dictionary (Woodbridge, Suffolk, Eng.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1995), p. 196; Amanda E. Lange, Delftware at Historic Deerfield, 1600–1800 (Deerfield, Mass.: Historic Deerfield, 2001), p. 122. For use and note of in situ examples, see Michael Archer, Delftware: The Tin-Glazed Earthenware of the British Isles (London: Stationery Office in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum, 1997), pp. 362–63.

For a seventeenth-century Dutch covered vase with a blue-red-green figural scene and octagonal shaft, see Erkelens, Queen Mary’s “Delft Porcelain,” p. 50; for octagonal form, see Hugo Morley-Fletcher and Roger McIlroy, Christie’s Pictorial History of European Pottery (Oxford: Phaidon, 1984), p. 224; for a seventeenth-century Dutch uncovered blue-on-white vase with a circular base, see John Carswell, Blue and White: Chinese Porcelain and Its Impact on the Western World, exh. cat., David and Alfred Smart Gallery, University of Chicago (Chicago: The Gallery, 1985), p. 160.

For Liverpool ca. 1760, see Frederic H. Garner and Michael Archer, English Delftware, 2nd ed. (London: Faber and Faber, 1972), figs. 82, 83. For Dublin ca. 1760–1770, see Peter Francis, Irish Delftware: An Illustrated History (London: Jonathan Horne Productions, 2000), pp. 134–40.

For an illustration of this bowl, see Louis L. Lipski and Michael Archer, Dated English Delftware: Tin-Glazed Earthenware, 1600–1800 (London: Sotheby Publications, 1984), fig. 1045.

One example is illustrated in John Black, British Tin-Glazed Earthenware (Buckinghamshire, U.K.: Shire Publications, 2001), p. 7.