Gustavus Hesselius, portrait of Stephen West, Sr. (1690–1752). Oil on canvas. (Private collection.) West acquired Rumney’s Tavern in 1724. The portrait is superimposed on a detail of a delftware mermaid plate used at Rumney’s Tavern.

Gustavus Hesselius, portrait of Stephen West, Sr. (1690–1752). Oil on canvas. (Private collection.) West acquired Rumney’s Tavern in 1724. The portrait is superimposed on a detail of a delftware mermaid plate used at Rumney’s Tavern.

John Greenwood, Sea Captains Carousing in Surinam, 1758. Oil on canvas. 37 3/4" x 75 1/4". (Courtesy, Saint Louis Art Museum.) Eighteenth-century prints and paintings have recorded numerous depictions of tavern life. These leave little doubt as to the large amounts of ceramics and glass that would succumb during a night of spirited revelry.

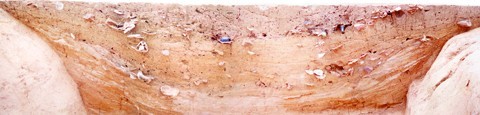

The Rumney/West cellar pit during the course of excavation with the contents of the eastern half removed. The once straight sides of the cellar were eroded away during its useful life. (Photo, Al Luckenbach.)

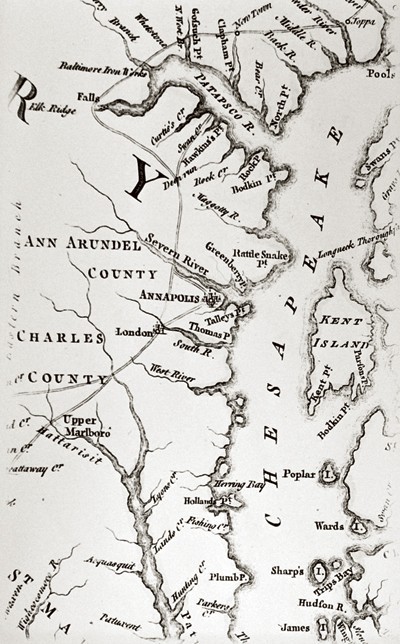

Detail of Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson’s Map of the Most Inhabited part of Virginia, containing the whole province of Maryland with Part of Pensilvania, New Jersey and North Carolina. 1754. (Courtesy, London Town Foundation.) This detail shows the important relationship of London Town, Maryland, to the colonial road system.

A circa 1840 painting of London Town from across South River. (Courtesy, Edmondo Collection.) This view, looking south from the ferry master’s house, shows a number of structures still surviving long past the town’s heyday.

Reconstructed view of London, Maryland. Lee Boynton, 1997. (Courtesy, London Town Foundation.) This painting was based on preliminary archaeological findings along Scott Street and the South River. A view of the William Brown House and Tavern across what was once busy Scott Street; today, an overgrown gully.

Drawing of the building footprints reconstructed from posthole patterns excavated along Scott Street. The area that has been archaeologically exposed so far is impressive for its dense, thoroughly urban layout.

The painstakingly careful excavations of the cellar, carried out over nearly five years, sometimes resembled an operating theater. Here, Lost Towns staff members can be seen working on a pig’s jaw and one of three delftware plates bearing a pagoda motif. (Photo, Al Luckenbach.)

This view of the southwest quarter during excavation shows the popularity of oyster shells as tavern fare. Ceramic and wine bottle fragments, bricks, pig bones, and a barrel hoop complete the assemblage. (Photo, Al Luckenbach.)

Examples of glassware recovered from the Rumney/West cellar. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) A scent bottle and medicinal vials are in the foreground of this grouping. The wine bottles represent the stylistic extremes recovered from the deposit, ranging in date from approximately 1700 to 1725. The trumpet shaped wineglass was a unique find; fragments with knopped stems were more common. One faceted wine glass had the inscription “God Save King George” and is believed to date from the coronation of George I in 1714.

Saucer and tea bowl fragments, China, ca. 1725. Porcelain. D. of saucer: 5". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This export porcelain saucer, along with small fragments representing a number of porcelain cups, are clear indications of the fashionable consumption of tea at the Rumney/West Tavern.

Chamber pot, Germany, ca. 1725. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 5". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This utilitarian object was found in close association with a “mermaid” plate.

Mug, England, probably London, ca. 1720. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 6 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This nearly complete example is one of a number of English brown stoneware mugs recovered. At least two bore the impressed “WR” excise stamp.

Mug, Staffordshire, ca. 1720. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 6 1/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Several Staffordshire white salt-glazed stoneware mugs were recovered. All had slip-dipped iron-oxide rims.

Pitcher fragment, England, ca. 1720. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 7". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Bowl, Staffordshire, ca. 1720. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 2 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This stoneware bowl and similarly sized delftware bowls may have been used as coffee cups.

Tea bowl and saucer, Staffordshire, ca. 1720. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. of tea bowl: 1 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These two objects were found lying side by side in the excavation.

View of a single excavation level in the southwest quarter of the cellar. This image shows the white salt-glazed stoneware tea bowl and saucer lying amongst the remains of an English stoneware mug, wine bottle fragments, and oyster shells. (Photo, Al Luckenbach.)

Coffee pot fragments, England, ca. 1720. Lead-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These English brown and off-white stoneware coffee pot fragments, including part of the handle and the acorn shaped finial from the lid, are taken as an indication of high status clientele in this circa 1725 context.

Mug, England, ca. 1720. Stoneware. H. 7 3/4". (Courtesy, Garry Atkins; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) An antique specimen of the lead-glazed stoneware represented by the coffee pot fragments illustrated in fig. 19.

Profile of plate, London, ca. 1720. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 8 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This low profile, lacking a foot ring, is typical of London manufacture. It was present on sixteen of seventeen excavated delftware plates.

Plates, London, ca. 1720. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 8 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Two of the four “sunower” plates recovered from the lowest levels of the cellar fill.

Plates, London, ca. 1725. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 8 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These English versions of a Chinese pagoda motif appeared on three excavated examples.

A tin-glazed earthenware mermaid plate is shown here in situ during the first weeks of excavation. It was found intermingled with fragments of a Rhenish chamber pot (and the remains of meals), in the cellar’s northeast quadrant. (Photo, Al Luckenbach.)

Plate, London, ca. 1725. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 8 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) One of three plates recovered that were decorated with the image of a mermaid. This motif now serves as the logo for the Historic London Town Park in Edgewater, Maryland.

Tea bowls, England, ca. 1725. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 1 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These delft tea bowls vary slightly in size, a tribute to the lack of standardization during this early period. Although quite delicate and thin by tin-glazed earthenware standards, they are still thicker than what could be achieved with the newer, white salt-glazed stoneware.

Bowls, England, ca. 1725. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. of tallest: 4 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Numerous delftware bowls attest to the popularity of punch at the Rumney/West establishmen

Spiked bowl, England, ca. 1725. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. to top of spike: 1 1/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This so-called “pineapple bowl” may have held butter or sugar instead. Note the interesting use-wear patterns that appear on all three edges of the pyramidal projection.

Chamber pot, England, ca. 1725. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 4 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.

Jar, North Devon, England, ca. 1720. Gravel-tempered earthenware. H. 10 3/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Although gravel-tempered earthenwares from the North Devon area are very frequently encountered at seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century archaeological sites in Anne Arundel County, this example from Rumney’s cellar is the most complete vessel yet recovered.

Jar, possibly Maryland, ca. 1725. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 9 3/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This tall, redware jar is a candidate for being a local product. Documentary evidence indicates that a potter named John Wamsley was active on the opposite shore of the South River during this time period.

Basin, Staffordshire, ca. 1720. Manganese-mottled earthenware. H. 4 1/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Pipkin, Holland, ca. 1700. Yellow-glazed earthenware. H. 2 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Two buff-bodied yellow-glazed earthenware vessels were recovered with profiles matching Dutch forms.

School children help screen plow zone soils for artifacts. (Photo, Al Luckenbach).

Profile of the cellar fill at the halfway point of excavation. A life-sized version of this illustration has now been mounted in Rumney’s cellar as a permanent exhibit. (Illustration, Severn Graphics.)

When Stephen West finally purchased the aging tavern in London Town, Maryland, he used part of his growing fortune to expand and upgrade the simple wooden structure. The year was 1724, and business was good (fig. 1). The tobacco seaport on the South River was thriving, and the tavern’s location—along the principal north-south road in colonial Maryland—meant that a constant stream of hungry and thirsty travelers flowed past the front door (fig. 2).

The addition that West built nearly doubled the size of the business previously started by Edward Rumney along Scott Street a quarter century before. The new tavern complex also included the construction of an outbuilding with a larger, more stoutly constructed storage cellar. This rendered the collapsing earthen cellar under the old wing of Rumney’s Tavern open to a new use.

Within a few short years the constant detritus of daily tavern operation—the bones of cows, sheep, pigs, and fish, oyster shells, fireplace ashes, broken glassware, and ceramics—filled the old cellar pit (fig. 3). Nearly five feet of trash, deposited in numerous distinct layers, preserved evidence of tavern life in London Town around the year 1725. Thus, a once functioning cellar now severed as a convenient repository for the tavern’s refuse.

The remains clearly represent the serving end of the operation, as few utilitarian artifacts evidencing food preparation were present. The evidence of high status meals suggests that an elite clientele was frequenting the establishment. In addition, an impressive assemblage of broken glassware and ceramics was discarded in the fill. Nearly a hundred vessels were eventually recovered, many in a largely reconstructable state. This diverse collection contained not only the predictable mugs, plates, bowls, and chamber pots typical of a tavern locale, but also specialty items like a “pineapple bowl,” tea bowls, coffee cups, and fragments of an early stoneware coffeepot.

Background

Towns did not form easily or naturally in the Chesapeake Bay environment. The many navigable rivers off the bay were settled by the middle of the seventeenth century with large numbers of planters engaged in the often-lucrative enterprise of growing tobacco. Tobacco plantations were clustered along these rivers, and each possessed its own wharf facility where the crops could be loaded for transport, and goods and merchandise off loaded in return. Indentured servants or slaves provided many of the manufactured items necessary for the plantation’s operation in small-scale cottage industries. There was no need for towns.

Over the period 1667–1719 the legislative assembly of Maryland, like that of its neighbor Virginia, tried repeatedly to forcibly establish towns.[1] Not only did they perceive towns from the perspective of the modern seventeenth-century Englishman—as economic and social engines of society—but they also sought a solution to a more basic problem. Trade was being conducted on such a geographically personal level that it was almost impossible to collect taxes. Forcing all trade to be conducted through legislative towns could solve this problem with the stroke of a pen.

In 1683, one such legislative act called for the formation of the Town of London on the South River in Anne Arundel County, Maryland. Unlike many such towns, which came to exist only on paper, or at best grew to support only a warehouse, tavern, and a few homes, London Town actually thrived. As the catch basin for a prosperous tobacco-growing region, the town became a thriving seaport. Unlike such well-known colonial towns as Williamsburg, St. Mary’s City, and Annapolis, London Town seems to have owed little of its success to political centrality. Even when the Anne Arundel County courthouse, which had been located at London Town between 1684 and 1695, was moved to Annapolis, the town’s status as an active port of trade did not seem to diminish, but rather continued to grow.

By the early decades of the eighteenth century, London Town had become perhaps the principal tobacco seaport in Maryland. Each year the tobacco fleet would gather on the South River in order to convoy their precious cargoes home. This fact alone had great significance for the nature of the town.

It is estimated from the known forty to fifty occupied lots that the town must have had a resident population that approached 300 during its heyday. But to this number must be added a fairly significant transient population. Not only was the tobacco fleet anchored off shore for weeks or months, awaiting a fickle crop (and leaving sailors with little more to do than wander the town), the planters from outlying areas had to arrive to conduct their business with factors and ship captains. Added to this was the fact that the principal north-south road in colonial Maryland ran through London Town and its ferries. A glance at a portion of the Jefferson and Fry map of 1751 (fig. 4) clearly indicates that, at least at this time, all roads led to London.

The exact cause of the eventual demise of London Town is clouded in the mists of time. One contributing factor may have been the removal of the tobacco inspection station in 1747. Just what would cause the Maryland Assembly to remove this important function from what must have still been one of the most important tobacco ports in the colony is unclear. Although river siltation has been suggested, or a change in salinity that fostered destructive marine worms, a more nefarious explanation involves the fact that a great many of the wealthiest citizens of London Town were relative newcomers from Scotland. Scottish factors, backed by banks and companies abroad, controlled much of the tobacco trade in the eighteenth century. Although not specifically recorded in this case, antipathy between these individuals and the native-born elite is well documented in the Chesapeake Region and may have led to competition.

What is quite clear is that the American Revolutionary War rang the final death knell. The British blockage of shipping clearly finished what was left of London Town as an economic hub (fig. 5). By the mid-1780s, the recorded land transactions dramatically demonstrate a combining of town lots into larger, agriculturally based farms. Perhaps a half dozen structures survived into the twentieth century. Today only two from the town period—one highly altered home on Larrimore’s Point and the William Brown House and Tavern—still exist on the landscape.

London Town Today

Of the original 100-acre town, twenty-three acres are currently owned by Anne Arundel County, Maryland, and are used as a park. Operated by the London Town Foundation as “Historic London Town,” the park today consists of beautiful woodland gardens and a single remaining structure from the town’s heyday. The brick William Brown House and Tavern is a circa 1760 brick structure that once sat alongside the Rumney/West Tavern on Scott Street—today little more than an impressive, overgrown gully.

For a quarter century, the Brown House, filled with colonial period furnishings, and the idyllic, modern, woodland gardens were interpreted for visitors experiencing the park. Although a few of the more informed visitors knew that a town once existed, in point of fact, it was like interpreting the last standing structure in Williamsburg and largely ignoring the reality that it once sat in the middle of a bustling sea port (fig. 6).

All this changed rather abruptly with the commencement of large-scale archaeological excavations in 1995. The on-going investigation is a cooperative effort between Anne Arundel County’s archaeological program, the London Town Foundation, and the county’s Department of Recreation and Parks.[2] To conduct these excavations, the team of professional archaeologists, historians, and laboratory specialists that comprise Anne Arundel County’s Lost Towns Project was augmented by hundreds of volunteers and students. Almost immediately, they began uncovering the remains of earthfast buildings[3] that once stood along Scott Street in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries (fig. 7). Among those discovered was the site of a tavern operation that had apparently spanned nearly sixty years, from roughly 1690 to 1750. Located at this important nexus of sea born and land transportation for over half a century, the Rumney/West Tavern must have been a well-known locale to travelers of the colonial period.

The Rumney/West Tavern Complex

The Lost Towns Project began excavations at the Rumney/West Tavern in 1996. The team excavated the overlying plow zone in over sixty 5 by 5-foot squares, recovering artifacts, and troweling the underlying ground surface. These excavations revealed postholes delineating a 40 by 25-foot earthfast structure divided into two equal sections that apparently represented two rooms. Excavation of one of the 20 by 25 sections revealed the presence of a trash-filled cellar hole measuring approximately 18 by 16 feet at the surface, and 10 feet long at the base.

Over the next five years the 4.5-foot deep cellar deposit was dug in four quadrants. Careful observance of micro stratigraphy lead to the delineation of over forty separate levels of trash, clay, and fireplace ash in each quadrant (fig. 8).

Dating the deposit was attempted in several different ways. The presence and absence of ceramics is, of course, one of the most frequently used methods, but this only results in a broad range of possible dates (circa 1680–1750). Tobacco pipes are also a mainstay of colonial archaeology in that they can provide specific chronological information. In this case, however, only one pipe was marked with the initials of a known maker, pipe maker William Manby (and his son, William), whose known period of output can be placed between 1689 and 1740.

A more novel approach involved a careful analysis of delftware decorative motifs recovered from the cellar. Eight separate motifs were compared to known, dated examples of delftware.[4] In this analysis, these eight motifs occurred ninety-two times on published dated examples with the average date being tabulated as the year 1723.8.[5]This result was viewed as highly significant since it corresponded to the historically documented date that the tavern transferred ownership from Edward Rumney to Steven West in 1724.

Various other studies, such as charcoal and pollen analyses, suggest that the cellar was filled with trash in a short period of time. When these indications are combined with the average date of 1723.8, West’s acquisition of the property in 1724 can be argued as the principal stimulus for the cellar deposit. More supporting data comes from dated window leads recovered in the nearby plowzone. The 1725 dates appearing on some clearly suggest that West was remodeling the tavern complex. The current hypothesis, therefore, is that after a new cellar was built, West must have no longer required the older cellar for its original storage purposes. Once he decided to use it as a trash receptacle, the constant flow of debris from an active tavern operation rapidly filled the pit.

The Rumney/West cellar contents represent a classic archaeological time capsule. Particularly abundant information concerning diet was recovered from oyster shells, animal bones, fish scales, etc., and dietary practices were indicated by the remarkable ceramic and glassware assemblages (figs. 9, 10).[6] The range of ceramics types found are summarized and discussed below.

The Ceramics from the Rumney/West Tavern

Archaeologists have become particularly used to dealing with ceramics in a highly fragmented state—which theoretically is of little consequence, since all of the necessary informational data frequently remains with the sherd, no matter its size. The many volunteers who participate in the excavations of the Lost Towns Project are always impressed when a tiny chip of pottery can be determined to be, say, a tea bowl made in China in the early eighteenth century. However, intact vessels or those that can be reconstructed add an exciting dimension to any ceramic analysis.

One of the most notable aspects of the assemblage from the Rumney/West Tavern is the predominance of English ceramics. A single Chinese porcelain saucer and small fragments from perhaps as many as seven porcelain tea bowls, a Rhenish stoneware chamber pot, a Rhenish mug, and an example of what may be a Dutch buff-bodied earthenware brazier are all the “foreign” elements that are present. Thus, close to ninety percent of the nearly 198 vessels recovered were of English manufacture.

This lack of non-English ceramics is a dramatic contrast to other excavations by Anne Arundel County’s Lost Towns Project at the 1649 Puritan settlements of Providence and Herrington. These contain examples of ceramics types from all over the world. Dutch ceramics are particularly well represented. As excavations at the Rumney/West Tavern continued, the contrast was quite distinct. The predominance of English wares at Rumney’s was considered a reflection of the effectiveness of the Navigation Acts passed in 1651, 1660, and 1664. These acts forbid the importation of non-English goods (such as Dutch delft) to its colonies.

As is often the case in archaeology, however, this elegant explanation was dispelled by the results from other digs in the town. Notably, excavations at a circa 1700 cellar deposit located at the other end of the London Town peninsula recorded a large number of delftware vessels whose origins appear to be Holland, Portugal, and Italy—but none from England![7] More research is needed to better explain these discrepancies, as archaeology often provides more questions than answers.

Porcelain

The fine, well-made porcelain imported from China that was found was associated only with tea drinking vessels. A saucer painted in under-glaze blue and then enhanced with red enamel and gilt over-glaze decoration was the closest to a complete vessel found in the Rumney/West deposits. This was accompanied by a handful of tiny sherds representing tea bowls. A minimum vessel analysis reveals that apparently as many as seven different bowls are present (fig. 11). Unlike most ceramic types recovered from the Rumney/West cellar, relatively small fragments of these vessels were found.

Rhenish Stoneware

Although German salt-glazed stoneware is common from colonial period sites in the Chesapeake region, including elsewhere at London Town, only two examples were present in the Rumney/West cellar—a sturdy, well-decorated chamber pot (fig. 12), and a single, highly fragmented example of a typical incised Rhenish tavern mug. The chamber pot was discovered fairly high in the layers of trash, and in close association with a delftware “mermaid” plate. It would have represented a notable physical improvement over the fragile tin-glazed earthenware examples that were relatively common at Rumney’s.

English Salt-glazed Stoneware

English brown and gray salt-glazed stoneware mugs, often called “Fulham” or “tavern mugs” by ceramics collectors are, as the name implies, a predictable find in a tavern assemblage. The Rumney/West cellar produced at least seven (and perhaps as many as nine) of these sturdy drinking vessels (fig. 13). Only two demonstrated the static “WR” excise mark.

Given that the earliest known dated example of English white salt-glazed stoneware is 1715, and that New World colonial archaeologists often use the start date of circa 1720, the presence of no less than ten vessels of white salt-glazed stoneware in this circa 1724–1725 deposit is most significant. The Rumney/West cellar is obviously a very early and well-dated context for this type of ceramic ware. Naturally, all specimens were of the earlier slip-dipped variety, and most possessed a brown rim caused by dipping into a manganese color. Four sturdy tavern mugs were included in this grouping (fig. 14), as well as a large and unusual handled pitcher (fig. 15). Interestingly, one small bowl form may in fact be a coffee cup (fig. 16).

Three tea bowls are among the white salt-glazed assemblage—one tea bowl and its saucer were recovered side by side in the same level (figs. 17, 18). This particular example stresses the fact that these bowls are exquisite, thin-walled expressions of this early vessel form. While still not matching the ideal of porcelain, the superiority of the newly invented white salt-glazed over the delftware versions of this kind of delicate vessel seems well established at this early date.

Although the attribution of coffee cup for the one vessel is rather speculative,[8] what is not speculative is the presence in the Rumney/West trash of an English stoneware coffeepot. This particularly rare item by itself speaks volumes about the tavern and its clientele (figs. 19, 20).

The Rumney/West Tavern operated during a period in which Chesapeake society exhibited increasingly rigid social ranking.[9] This was also a period during which taverns and coffee houses became increasingly important settings in which English speakers on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean not only conducted business, but also created and critiqued fashions and fashionable behavior.[10] The fact that on the South River in colonial Maryland the town of London expressed such behavior by the mid-1720s is most notable.

Tin-glazed Earthenware (delftware)

The delftware plates recovered from the Rumney/West cellar are perhaps the most interesting vessel forms present in this type of ceramic. Except for a single example—a chinoiserie pattern with a foot ring—all were of a distinctive flat-based form usually attributed to London manufacture (fig. 21). Most were decorated (twelve of seventeen), and all the decorated London plates had annular rings as border decoration. Intriguingly, “sets” of plates with identical decoration were recovered. Four examples were found which had a floral “sunflower” pattern (fig. 22), while three others displayed an impractical looking “pagoda” (fig. 23).

One of the first plates discovered at the beginning of the excavation in 1996 depicted a rather homely looking mermaid (figs. 24, 25). This “sea creature” as they are sometimes called in the literature, was eventually found on three of the annular ringed London vessels. Two different respected ceramic experts suggested that the presence of such plates might well be taken to indicate that the “Sign of the Mermaid” might have been the way the public denoted what we are calling here the Rumney/West Tavern.[11] This would appear to be appropriate in a seaport setting. Given that plans are underway for the eventual reconstruction of this building, the visage from this plate may once again swing from a wooden sign in front of the establishment.

But the London Town mermaid has not had to await the reconstructed building. As an indicator of the park’s mission having expanded from the interpretation of the William Brown House and Tavern to that of the entire seaport, the mermaid has been employed for several years as the logo of the London Town Foundation that operates the historic facility. Despite her appearance, no one can dispute the mermaid’s appropriate maritime connotations.

As has already been discussed, the Rumney/West Tavern appears to have served a wealthy clientele accustomed to dining using delftware and porcelain and, more importantly, engaging in social drinking of wines, punches, coffees, and teas. This is evident in the varied group of tin-glazed earthenware cups and bowls. A pair of matching tea bowls was recovered whose remarkably thin walls witness the attempt to reproduce the delicacy of porcelain in a difficult medium (fig. 26). Their painted border decoration corresponds to examples found at the Vauxhall pottery kiln site in London.[12]

A total of ten bowls was recovered, ranging in size from 4.5 to 7 inches (fig. 27). Although some of the smaller examples might be suspects for coffee cups, most, if not all, were undoubtedly for the consumption of alcohol. Interestingly, none of the large communal bowls often seen in contemporary paintings of tavern scenes were recovered. The small polychrome bowl in figure 27 is also a perfect match for a motif found at the Vauxhall production site,[13] while other, fragmentary bowls are evocative of the “sunflower” plates described earlier.

A delftware object of particular significance from the Rumney/West cellar is an unusual bowl possessing a central, pyramidal spike in its base (fig. 28). Similar vessels have been termed “pineapple bowls,” assuming that such fruit (or limes, oranges, etc.) might be impaled on the spike to create an early form of rum punch. Other experts have considered alternative explanations to be preferable, such as butter or sugar containers. Regardless of its actual function, the vessel is clearly a rare and highly specialized item. At least two extant examples in museum collections are known, while three examples were recovered from the Vauxhall salvage excavations.[14] This first New World example speaks volumes for the kind of tavern operation involved along the South River in colonial Maryland.

The Rumney/West assemblage of tin-glazed earthenwares is rounded out by no less than five plain white chamber pots (fig. 29), and by three galley pots.

Other Earthenwares

As stated, the low number of utilitarian, cooking types of vessels in the Rumney/West ceramic assemblage is striking. This implies that food preparation, or at least the disposal of its debris, occurred elsewhere. A single large jar of North Devon gravel-tempered ware is the only example recovered of this well-known, and sometimes abundant, redware ceramic type (fig. 30). This finding further reinforces the distinction between excavations at London Town and those at the earlier town of Providence where this coarse earthenware was present in numbers often approaching eighty percent. Other redware forms found at Rumney’s included three jars, four milk pans, and a bowl. One example of a reconstructed jar is shown in figure 31. These lead-glazed redwares are so universal in construction and materials that they are extremely difficult to attribute to a source of production. Interestingly, historical documents indicate that a potter named John Wamsley was operating during this period, and was apparently located directly across the South River ferry from the Rumney/West Tavern. The possibility that these redwares could be Wamsley’s products is most intriguing but unproven. Unfortunately, efforts by the Lost Towns Project to locate the pottery kiln site have been unsuccessful so far.

Also readily recognizable is a steep sided pan of buff-bodied material glazed with mottled manganese. It almost certainly was produced in the Staffordshire region of England (fig. 32), as was a single small cup with yellow and brown glaze recovered in fragmentary condition.

Finally, two probably Dutch products represent the only foreign earthenware from the assemblage. A pipkin and a highly fragmented brazier seem to match known Dutch forms (fig. 33).

Vessel Types

While the classification of ceramics by type provides a useful means of ordering and describing the contents of the Rumney/West cellar, it fails to adequately depict the overall functionality of the assemblage. For this reason archaeologists have come to increasingly rely on the functional classification of vessels, irrespective of type. While describing the numbers and percentages of bowls, plates, cups, etc. found during excavation has a certain utility in itself, it is the capacity to compare these results with data from elsewhere that greatly enhances the comprehension of their significance.

Fortunately, a body of such data exists from excavations done in Annapolis several years ago. Annapolis, which became the colonial capital of Maryland in 1695, sits on the Severn River, the next river system to the north of London Town. Although extensive excavations have been undertaken at the Providence settlement, precursor to Annapolis, this data falls at a chronological point (circa 1649–1680) too remote to provide any useful comparisons to the Rumney/West assemblage. However, the 1997 salvage excavation along Main Street in Annapolis conducted by R. C. Goodwin and Associates provides a perfect body of comparative data.[15]

The site called Freeman’s Ordinary is ideal for a number of reasons. First, it was generally contemporaneous, containing wares from North Devon (1670s) to early white salt-glazed stoneware (1720s). Second, it is geographically proximate, being only three miles away as the crow flies, and like Rumney’s, the Freeman’s assemblage is urban in nature. Finally, both ceramic assemblages show a fairly low presence of utilitarian ceramic vessels (other than chamber pots). This suggests that both are deposits generated from the serving end of the tavern operations and further indicates the utility of Freeman’s as a comparison for the Rumney finds.[16]

Both taverns had significant numbers of wine bottles, wineglasses, mugs, and bowls, strong evidence of the amount of alcoholic consumption that occurred at both establishments. One difference is the prominence at Freeman’s of large numbers of brass wires that once held stoppers on the wine bottles, a phenomenon not seen at Rumney’s. The presence of a nearby Annapolis brewery in the late seventeenth century may provide the explanation for this, and it is speculated that the clientele at Freeman’s was consuming more beer while Rumney’s patrons drank wine.

Another difference is the presence of tea bowls, a coffee pot, and what might well be coffee cups at Rumney/West, but not at Freeman’s Ordinary. If rum punch is the explanation for the “pineapple bowl” from Rumney’s, then this constitutes another example of what would appear to be high status drinking.

Perhaps the most dramatic dichotomy between Freeman’s and Rumney’s is in dinner plates. Rumney’s has numerous, often highly decorated plates, while Freeman’s has none. Two explanations for this can be derived from the missing parts of any such archaeological assemblage—that which was not thrown away or which otherwise does not survive. Wooden trenchers, for example, would not be preserved to be excavated except in the most unusual of circumstances, circumstances not present at either of these two cellars.

A second explanation also involves plates made of materials not discarded for archaeologists to recover such as pewter. During the colonial period, pewter was a valuable metal that was easily reprocessed into other forms. As a consequence, it was not generally thrown away, and not generally recovered on most archaeological sites of the period. Rumney and Freeman’s are not exceptions in this regard.[17]

So, were the missing plates from Freeman’s wooden or pewter, or did they exist at all? While the answer may never be known with certainty, a number of evidentiary lines indicate that Freeman’s was serving a clientele of lower social status than Rumney’s—and would therefore be more likely to have been using wooden trenchers.

One has already been mentioned, the possible beer/wine dichotomy, and the tea/coffee drinking which occurred only at Rumney’s. Historical documents provide another. Records indicate that workmen employed in building the new state house in 1697 were staying at Freeman’s. If Freeman’s Ordinary was accommodating a clientele of laborers, it probably would not also have had elite customers. Finally, a number of artifacts reinforce this conclusion. These include higher status items such as a scent bottle (see fig. 10), a highly decorative sword hanger, and such unique ceramic finds as the “pineapple” bowl found at Rumney’s.

Summary

The ceramic assemblage recovered from the Rumney/West Tavern is unusual both for its extensive nature and for its well-preserved and datable context. Together with the analyses of its floral and faunal remains, it provides a remarkably detailed look at upscale tavern life in London Town, Maryland, circa 1725. The utility of such an assemblage for other comparative archaeological studies is of the highest order.

But surprisingly, the greatest contribution that this archaeological assemblage and its excavations have made may not lie in the artifacts or the technical aspects of historical archaeology, but in the public’s awareness and personal participation in the recovery of the past. The Lost Towns Project is a public and educational program (fig. 34). Hundreds of volunteers assisted the professional staff in the excavations, lab processing, research, and analyses involving the Rumney/West Tavern complex. Thousands of school children visited the excavations as they occurred under our white tent.

As the most visible archaeological feature at the park, the excavations proceeded slowly—not just for the normal, careful scientific reasons. Five years of painstaking excavations occurred before the last cultural deposit was removed, but this length of time was partly because of the importance of the excavation as an educational tool.

Edward Rumney and Stephen West’s tavern continues to educate. Today, the site is a permanent exhibit centered around a single life-sized photograph of the deposits as they appeared at the half-way point of the excavations (fig. 35). Over 5,000 school children alone visit each year. After two and a half centuries, the tavern still draws a crowd.

For further information, see John W. Reps, Tidewater Towns: City Planning in Colonial Virginia and Maryland (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1972).

Other institutions providing assistance include the Anne Arundel County Trust for Preservation, the Maryland Historical Trust, the National Park Service, the Kaplan Foundation, and the National Geographic Society. Architectural research support has been provided by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

In earthfast construction, the principal structural members of a building are set directly into the ground. For further information, see Cary Carson, Norman F. Barka, William M. Kelso, Garry W. Stone, and Dell Upton, “Impermanent Architecture in the Southern American Colonies,” Winterthur Portfolio 16, no. 2/3 (summer/autumn 1981): 135–96.

Louis L. Lipski, and Michael Archer, Dated English Delftware: Tin-Glazed Earthenware 1600–1800 (London: Sotheby’s, 1984).

Al Luckenbach and John Kille, “Delftware Motifs and the Dating of Rumney’s Tavern, London Town, Maryland (ca. 1724),” American Ceramic Circle (in press).

Al Luckenbach and Patricia Dance, “Drink and Be Merry: Glass Vessels from Rumney’s Tavern (18AN48), London Town, Maryland,” Maryland Archeology 34, no. 2 (1998): 1–10.

Lisa Plumley and Al Luckenbach, “Tracing Larrimore Point Through Time: Excavations at 18an1084,” Maryland Archeology 36, no. 1 (2000): 11–24.

Jonathan Horne made this suggestion, partially based on the known presence of a coffee pot, and partially on the use of a similarly sized cup in a delft tile store front picture, Dish of Coffee Boy.

Allan Kulikoff, Tobacco and Slaves: The Development of Southern Cultures in the Chesapeake, 1680–1800 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986.)

John Brewer, The Pleasure of the Imagination: English Culture in the Eighteenth Century (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1997).

Ivor Noël Hume and Jonathan Horne both made this suggestion in independent personal communications.

Dennis Cockell, “Some Finds of Pottery at Vauxhall Cross, London,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 9, no. 2 (1974): 121, 129.

Ibid., p. 126.

Frank Britton, London Delftware (London: Jonathan Horne, 1986), p. 71.

April Fehr, Suzanne Sanders, Martha Williams, David Landon, Andrew Madsen, Kathleen Child and Michele Williams, “Cultural Resources Management Investigations for the Main Street Reconstruction Project, Annapolis, Anne Arundel County, Maryland,” report to the City of Annapolis, 1997.

Al Luckenbach, Patricia Dance, and Carolyn Gryczkowski, “Taverns and Urban Life in the Early 18th-Century Chesapeake: A Comparison of Two Assemblages from Anne Arundel County, Maryland,” paper presented at the Society for Historical Archaeology, Atlanta, Georgia, 1998.

Ann Smart Martin, “The Role of Pewter as Missing Artifact: Attitudes Towards Tablewares in Late-Eighteenth-Century Virginia,” Historical Archaeology 23, no. 2 (1989): 1–27.