Mug, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Bisque-fired earthenware. H. 5 7/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens; unless otherwise noted, photos by Gavin Ashworth.)

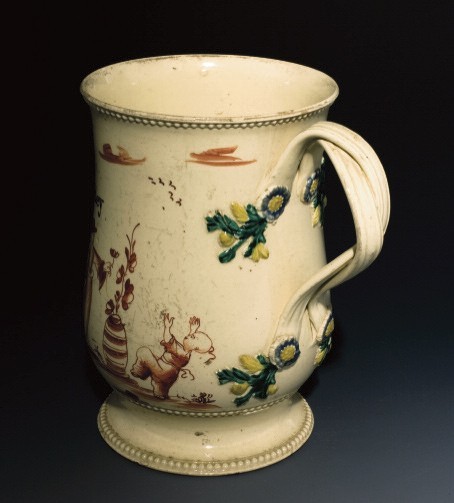

Mug, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1770–1780. Creamware. H. 5 3/16". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Sprig mold, Salem, North Carolina, ca. 1780. High-fired clay. L. 2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The back of this mold bears the initials “RC” for Rudolph Christ. This is the only surviving sprig mold from the Salem pottery.

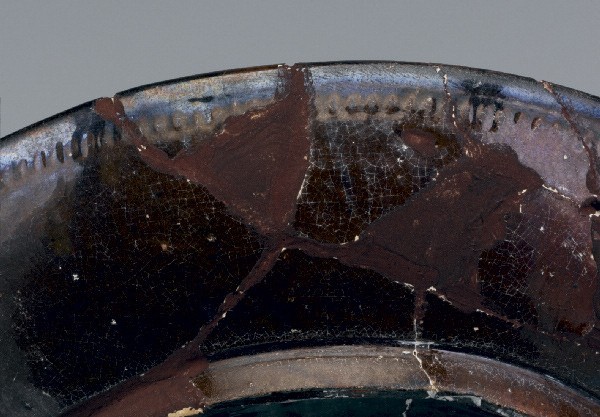

Detail of the base of the mug illustrated in fig. 1. The use of a roulette to finish the foot in this manner is very unusual and has not been seen on any Staffordshire examples or on any of the creamwares produced by John Bartlam at Cain Hoy.

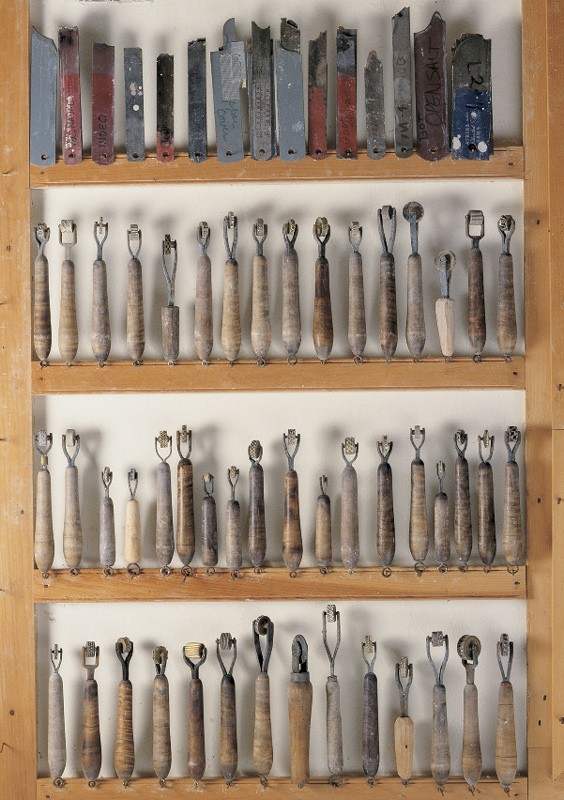

An assortment of roulettes and related trimming tools used by present-day potter Don Carpentier in the manufacture of British-style creamwares and pearlwares. (Courtesy, Don Carpentier.)

Mug fragment adhered to kiln prop, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Mug fragments, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) These fragments show the fluted gadrooned rouletting seen on the mug illustrated in fig. 1.

Teapot, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Lead-glazed earthenware. L. 7". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) It is unclear whether this example, one of the most important ceramic objects of eighteenth-century America, was produced by William Ellis during his 1774 visit to the Salem pottery or was a later creation of Rudolph Christ.

View of the opposite side of the teapot illustrated in fig. 8.

Detail of the base of the teapot illustrated in figs. 8 and 9.

Teapot spout, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Handled cup fragments, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The sprigging on the handle terminals, which matches that on the terminals of the teapot illustrated in fig. 8, and the tortoiseshell glaze on the teapot and the matching saucer shown in fig. 13 show that these teawares were being manufactured in sets.

Saucer fragment, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Mug or coffee cup, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Mug or teacup, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The chevron roulette shown along the rim of this vessel and other fragments is a detail often seen on British white salt-glazed teawares.

Mug or teacup fragment, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

“Fineware” fragments, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Mug fragment, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The lines on this straight-sided tankard appear to be the result of turning on the lathe, to simulate a style of creamware popular in the 1770s.

“Fineware” fragments, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Bisque-fired and lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

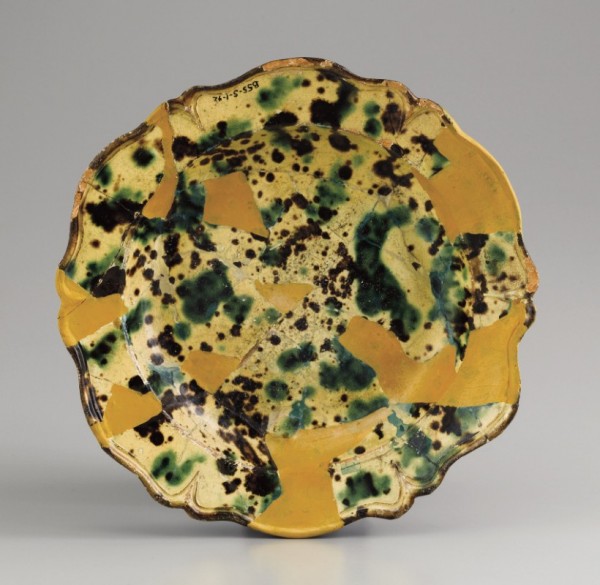

Plate, attributed to Rudolph Christ, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1786–1789. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 9 5/8". (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Beaker and mug, attributed to Rudolph Christ, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1786–1789. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. of mug 4". (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Saucer dish and bowl, attributed to Rudolph Christ, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1786–1789. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. of bowl 7 5/8". (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Teabowls and saucer, attributed to Rudolph Christ, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1786–1789. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. of teabowl 3 3/8". (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Plate mold, attributed to Rudolph Christ, Salem or Bethabara, North Carolina, 1781–1789. Plaster. D. 10". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

Plate, attributed to Rudolph Christ, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1786– 1789. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 9 3/4". (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Detail of the edge of the plate illustrated in fig. 25 showing the red clay body beneath the white slip.

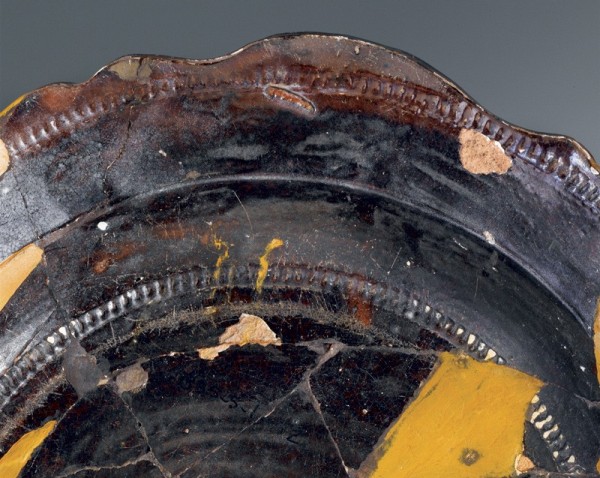

Detail of the reverse of the plate illustrated in fig. 25. Note the two parallel bands of beaded roulette.

Dish, Rouen, France, 1780. Tin-glazed earthenware. L. 16 3/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Saucer fragment, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Saucer fragment, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Plate mold, Rudolph Christ, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1789. Plaster. D. 10 7/8". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

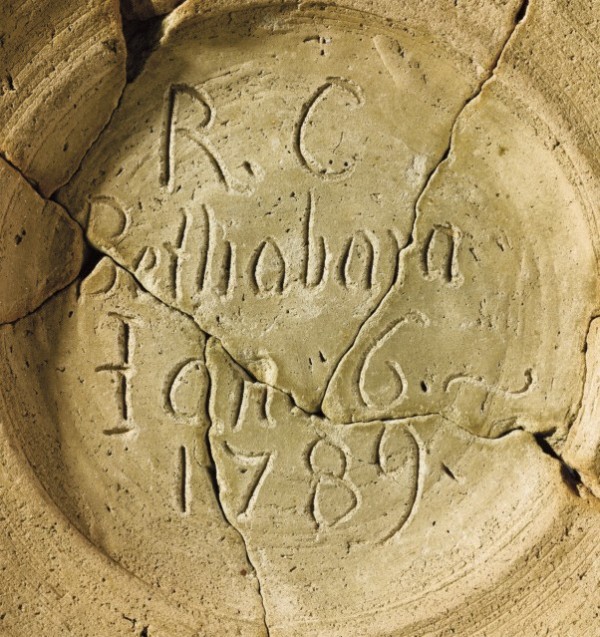

Detail of the inscription on the plate mold illustrated in fig. 31: “R. C / Bethabara / Jan. 6.~ / 1789.”

Plate, probably Staffordshire, ca. 1790. China glaze. D. 10". (Private collection.) This English example of a twelve-sided plate is very similar to the plate mold illustrated in fig. 31.

Detail of the plate mold illustrated in fig. 31.

Plate mold, attributed to Rudolph Christ, Salem or Bethabara, North Carolina, 1786–1789. High-fired clay. D. 8 5/8". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

Plate fragments, Salem, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The rim fragment on the left has the bead-and-reel pattern often used on English white salt-glazed plates. The center example is the popular feather-edge pattern used exclusively on English creamware. The fragment on the right shows fine swags in a neoclassical pattern similar to those used on English pearlware and creamware plates.

Plate fragments (obverse and reverse), Salem, North Carolina, 1780–1786. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) Note the use of roulette decoration on the reverse of the left fragment.

Plate fragments, Salem, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Plate fragments, Salem, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Plate fragment, Salem, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) This plate fragment has hand-painted manganese decoration imitative of the chinoiserie decoration popular on late-eighteenth-century British creamware and pearlware.

Bowl fragments, Salem, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) These fragments show the exterior (top) and interior (bottom) of a small creamware punch bowl. The manganese decoration is also in the chinoiserie style.

Plate fragments, Salem, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) These fragments from a Queens-shape plate were decorated with cobalt on a pale blue faience glaze, in a style reflecting contemporary English china-glazed wares.

Teapot fragments, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The teapot was probably made during William Ellis’s tenure at the Salem pottery, ca. 1774.

The significance of the immigration circa 1763 of Staffordshire potter John Bartlam to Charleston, South Carolina, and his production of both refined earthenware and soft-paste porcelain on American soil have been championed in a number of recent publications.[1] A lesser-known aspect of this story is the role of journeyman potter William Ellis, one of Bartlam’s highly skilled workers recruited from the Staffordshire industry. After Ellis left Bartlam’s employment, he became part of the Wachovia community in Salem for a short period (December 1773 to May 1774), working with Gottfried Aust, at that time the community’s master potter, and Rudolph Christ, a Moravian journeyman potter. Ellis shared his technological expertise and instructed the Wachovia potters in the making of Staffordshire-style earthenwares, which, at the time, were the de facto production items of the Staffordshire industry.

In the second half of the eighteenth century virtually the entire Western world relied on imported British tableware, and the Carolina piedmont was no different. Fragments of Staffordshire creamware have been found in large quantities on archaeological sites throughout North America, reflecting the international demand for these industrially made tablewares. The Moravians’ interest in producing British-style tableware was motivated primarily by profit; they recognized its potential to be a distinguished sideline to their own coarse redwares—heavily potted, wheel-thrown dishes, jars, and jugs.[2]

The remarkable baluster-shaped mug illustrated in figure 1 is perhaps the most emblematic of the surviving artifacts resulting from Ellis’s sojourn at the Salem pottery. The mug, which is bisque-fired but unglazed, was among a group of wasters recovered from Lot 49 by Stanley South in his 1968 archaeological investigations of the Salem pottery.[3] Made from refined earthenware clay, the Salem mug invokes a vocabulary nearly identical—in size, shape, and decorative details—to Staffordshire-style mugs that were fashionable in England and America during the 1770s and 1780s (fig. 2).

A “Stranger Journeyman Potter”

William Ellis was born in Hanley, England, in 1743 and grew up in the center of the Staffordshire potting industry.[4] Nothing is known about his training, but Ellis was competent enough to have been recruited by Bartlam about 1770. Ellis probably began his work in America at Bartlam’s failed “China and Earthenware Manufactory” in Charleston, which opened in late 1770. By October 1772 Bartlam had encountered severe economic problems and relocated his works to Camden, South Carolina; it is assumed that Ellis accompanied him.[5]

The first mention of Ellis at Salem comes from the detailed and carefully maintained documents of the Moravian Church, which record the arrival of a “stranger journeyman potter by the name of Ellis” in December 1773.[6] From that date until his departure in May 1774, Ellis was able to transmit some of the key production techniques used in the making of English creamware, and possibly English salt-glazed stoneware, to the Salem potters. Before this, Gottfried Aust and the other Moravian potters worked only with the relatively thick and heavy earthenware forms characteristic of European potting traditions, making ready use of the coarse red clays of the North Carolina piedmont. There is little historical evidence to suggest Aust embraced the “finewares” techniques that Ellis proffered, but his subordinate Rudolph Christ certainly did.[7]

William Ellis was not the first “stranger” potter to make the Moravians aware of the practice of “glazing and firing Queens Ware.” An unnamed English potter, likely also a John Bartlam associate, visited Wachovia in the summer of 1771 and introduced Aust to “Queensware” and “Tourtise Shell” at Aust’s Bethabara pottery.[8] A single fragment of a cream-colored beaker, recovered from the kiln waster dump of that shop, might be associated with those demonstrations.[9] While this individual was not invited to stay, his technological expertise had its effect on the Moravian community, whetting the appetite of many to manufacture “finewares.”

By the end of July 1771 Aust had moved his Bethabara operation to the pottery in Salem on Lot 48 and continued to make Germanic-style earthenware for the community, which very much needed such utilitarian wares. When Ellis arrived in 1773, however, Aust agreed to “make an experiment of new pottery.”[10] Ellis supervised the construction of a new kiln, adjacent to the pottery, that would be suitable for firing queensware. (South located the archaeological remains of this kiln during his 1968 excavation along the north property line of Lot 49. Most of the kiln structure, which is contained on Lot 48, has yet to be archaeologically explored.)

Technical expertise at building a specialized kiln was just one of the necessary ingredients of the Staffordshire oeuvre. Perhaps most important, the refined Staffordshire table- and teawares required a suitable clay body—something much finer and lighter in color than the coarse earthenware bodies in use at Salem and Bethabara. Ellis would have known this, given both his Staffordshire experience and his use of the white clay that Bartlam had successfully employed in South Carolina. In order to take full advantage of the new ceramic technology, securing a supply of fine, white earthenware clay was critical. Moravian records confirm that such a source was found, and that at least “2 loads white clay” were provided to Ellis during his short stay in the Moravian community.[11] It is unclear whether Ellis helped locate the source of the clay, but it is probable that he did.

Beyond simply finding an appropriate clay source, Ellis’s tutelage presented a methodology quite different from the Moravian potting tradition. The Staffordshire ceramic industry had risen to prominence through industrialization of the production process, which resulted in standardized ware types and vessel forms. English table- and teawares were made using the same methods, molds, and tools employed by virtually all of the Staffordshire factories. Shared tools and materials gave the wares a uniformity that, by the 1770s, was the embodiment of the modern factory assembly line. The introduction of these techniques into an Old World tradition must have generated considerable excitement—and perhaps consternation—within the Moravian pottery community.

Two of the factory production methods utilized by the Staffordshire potteries are most relevant here. One is the use of molds, a manufacturing method in place since the 1740s and one that generally is well understood. The other is the use of the turning lathe, which rarely is associated with ceramic production in America. Ceramic historian David Barker asserts that the lathe was a standard production tool of the Staffordshire industry from the 1720s onward and was used to trim all hand-thrown hollow wares.[12] The broken fragments from John Bartlam’s Cain Hoy site—illustrated in figure 5 of “Staffordshire in America” by Lisa Hudgins in this volume—provide unambiguous evidence of lathe turning, and it only makes sense that Ellis would have included the use of this tool in his instructions to the Moravians.

Perhaps the most critical aspect of the Staffordshire methodology was the technology related to glazing and firing. The refined earthenware body necessary to produce creamware requires higher temperatures and more sustained firing than those used for lead-glazed redwares. Coal was the standard fuel for the factory kilns in Staffordshire. In America, however, Ellis must not only have learned to fire Bartlam’s creamware kiln with wood but developed new abilities to control the kiln temperatures and environment.

In summary, during the short span of five months that Ellis stayed in Salem, he would have tutored Aust and Christ in the following: sourcing and refining suitable white earthenware clays; techniques for producing plate, sprig, and extruded handle molds; using a potter’s lathe to trim and apply rouletted decoration on hollow ware; preparing and applying glaze material; and appropriate firing techniques, including the use of specialized kiln furniture.

Ellis must have succeeded in most of these endeavors to have “made a trial of burning Queensware also another with Stoneware.”[13] The Moravian records further confirm that “the processes necessary for [queensware and stoneware] are pretty well made known to us”—presumably by Ellis. Not until nearly five years after his departure do references to continued interest in the production of finewares appear in the Moravian records. In January 1779 Aust reported to the Aufseher Collegium that Christ had carried away “several forms which are used for flowers for the fine pottery.”[14] Those “forms” have been identified as small molds used to create sprigs for handle terminals on mugs, tankards, and teapots (fig. 3).

The Fineware Pottery in Salem

In September 1780 Rudolph Christ, though still a journeyman under Gottfried Aust, requested permission from the Aufseher Collegium to operate a “fine pottery” in Salem. Christ explicitly understood the importance of such a pottery keeping its white clay source separate, to avoid contamination from the red clay used for the “rough pottery.” Christ, too, was anxious to separate himself from Aust and to focus on the “manufacture of white, black, and salt pottery”—all products emulative of Staffordshire-style ceramics.[15]

The friction between Aust, the shop’s master, and the ambitious Christ has been well documented in the contentious, at times vitriolic, testimony found in the Moravian records, and their personal problems continued to plague the Salem operation.[16] Christ’s unrelenting requests to start a “finewares” manufactory perhaps helped determine the nature of a new contract with Aust in December 1781.[17] Of particular significance, Christ would be responsible for preparing his own clay, and he was to erect a fence separating Aust’s workspace from his own. The contract also specifies vessels for which Christ would receive piece payment—queensware or Staffordshire-style teawares and double-handled mugs:

Pieces which have to be handled more carefully

Tea pots

Bowls

Ware that are sold at a price over 1 penny

Bowls

Half pints

Quarts

Tea cups (from the latter six saucers and six cups

charged by the dozen) of queens ware.

Ware that has to be made with special care

Sugar cans

Tea pots

Quart and pint with double handle

Formed plates and dishes[18]

As of this writing, no surviving intact objects are known that can be attributed to the production of fineware at the Salem pottery. South’s archaeological excavations, however, did reveal a remarkable pit filled with wasters of “fine” pottery—tangible ceramic evidence of Ellis’s contribution in introducing Staffordshire ceramic technology to Moravian potters.

The contents of the waster pit have generated discussion of the date of the materials found within. The pit was beneath the stone foundation of an addition to the pottery shop built in 1798, providing a definite end date for the deposit. South contends that the pit was filled in during the 1795–1798 period, based on the presence of stoneware saggars that could correspond to a 1795 reference that Christ had begun to make stoneware.[19] South identifies the sprigged and rouletted fragments found in the pit as failed examples of Christ’s production of fineware, although he does not totally discount the possibility that some of the wares might be Ellis’s 1774 work. John Bivins has a different interpretation of the wasters, however; he specifically attributes the contents to the hand of William Ellis:

The excavated ware here is associated with the experimental kiln built on Lot 49 in 1773 by Aust and the itinerant potter William Ellis for the purpose of instructing the Salem potters how to make and fire the Queensware or “fine pottery” forms with which Ellis was familiar. These pieces are evidently by the hand of Ellis himself; they might be considered a bit difficult for the first efforts of potters such as Aust or Christ who had not been familiar with the large amount of handwork needed to make these complex pieces.[20]

In dissent, Brad Rauschenberg wrote in 1991 that “Despite the fair amount of documentation of his work in the records, no ceramics evidence has been found that can be attributed to the Englishman [Ellis].”[21]

While it is difficult to identify with certainty the maker (or makers) of the Staffordshire-style ceramics recovered from the waster pit, the importance of these archaeological finds of fineware cannot be overstated. They suggest that even though the local white clay was not ideal, it was adequate for the manufacture of several types of relatively thin creamware forms. Furthermore, they embody several important technological attributes of Staffordshire production methods. A roulette wheel was used to create the fluted gadrooned molding on the lip and foot of the Staffordshire-style mug shown in figure 1. An unusual use of another roulette, found on the base of the mug, is atypical of a Staffordshire product (fig. 4). Roulettes were the stock-in-trade of the Staffordshire earthenware industry in the second half of the eighteenth century (fig. 5). An immense variety of decorative beadings was designed for many creamware and pearlware hollow wares. The roulette wheel customarily is made from brass and attached to a wooden handle; a rudimentary roulette can be carved from plaster or fired clay. In British factories, this type of decoration was carried out while the vessel was supported horizontally on a lathe, although the extent to which Moravian potters employed such a device is unclear.

One particularly evocative “kiln accident,” illustrated in figure 6, is the rouletted base of a small earthenware mug frozen to its kiln stand. This pint mug retains the crispness of the roulette’s zigzag impressions, made when the clay body was still soft. Such impressions, also found on other Salem fragments, are not readily associated with known English examples, suggesting they might have been designed and made at Salem. The mug base and other fragments of baluster-shaped mugs (fig. 7) prove that these objects were not unique examples but were, in fact, made in quantity.

Without question, the highly decorative twisted strap handles are the most prominent elements of these mugs. They were created using an extruder and a special die to create the ribbing. A review of Staffordshire creamware examples suggests this style of handle was introduced into the ceramic industry in the mid-1760s and reached its height of popularity about 1780.[22] Intertwined handles continued to be a popular English detail used on china-glazed mugs, tankards, jugs, and tea- and coffeepots well into the 1790s.[23] If Ellis introduced this specific element during his stay with the Moravians in 1774, it would have been on the leading edge of the fashionableness of the style.

Rouletted elements and twisted handles were incorporated in the production of the ambitious teapot shown in figures 8 and 9. This amazing object is perhaps the best expression of the successful transfer of Staffordshire technology in the American environment. Decorated with sponged manganese simulating tortoiseshell, the teapot survived bisque firing but was damaged in the glaze firing. As with the baluster mug, it has sprig handles and rouletted beading around the rim and the base (fig. 10)—standard elements in Staffordshire creamware products. In contrast to the thrown and hand-modeled elements of the traditional but serviceable Moravian teapots, the spout on this example was created using a mold (fig. 11). Fragments of a handled cup and saucer with applied sprigs (figs. 12, 13) and tortoiseshell glaze identical to those used on the teapot illustrated in figure 8 were also recovered.

The overall shape, details, and competency of the baluster mug and the teapot argue for the hand of a master potter experienced with the manufacture of English products, not the unpracticed eye of one of the Moravian potters. The mug and teapot could be attributed to William Ellis directly, but we have no clear evidence from the archaeological context in which they were found to say they were made in 1774. The fact that both glazed and bisque forms were recovered demonstrates that the waster pits contained objects from multiple firings, possibly over a longer period of time than the five-month window of Ellis’s visit. We simply do not know the earliest date for the objects.

Other specimens with intertwined handles that were recovered from the waster pit show less proficiency; perhaps they represent examples of the “quart and pint with double handle” mugs listed in Christ’s contract with Aust. The shape of the small, nearly straight side cup illustrated in figure 14 is unusual and seems to be a poor imitation of contemporary Staffordshire coffee cups. Likewise, the barrel-shaped specimen shown in figure 15 is only vaguely reminiscent of Staffordshire shapes. While both appear to be practical forms, their shapes are amateurish and the execution of the twisted handle and sprig-modeled terminals is clunky; surely these are products of the aspiring potter of fineware, Rudolph Christ.

Additional wasters, both glazed and unglazed, illustrate varying degrees of refinement in the use of sprigging and rouletting (figs. 16, 17). The mug fragments that are covered in a dark green lead glaze (figs. 14-16) are not typical of any known Staffordshire glaze treatment.

One of the dark green glazed mugs shows some indication of lathe trimming (fig. 18). Evidence of lathe use by Moravians potters is circumstantial; no mention of the device appears in any of the inventories made of the pottery shop during the eighteenth century, although, of course, it was an essential tool for the woodworkers and gunsmiths in Bethabara and Salem.[24] Several of the creamware forms produced by Bartlam give clear indication of lathe turning (see Hudgins, “Staffordshire in America,” fig. 5). The incredible thinness of other recovered bisque wasters supports the claim that Moravian potters utilized lathes, since lathe trimming is necessary to achieve this effect (fig. 19).

While the attribution of the various British-style hollow wares recovered from the waster pit on Lot 49 may be debated, without question they represent one of the most important assemblages related to early American ceramic history. Stylistically, many of the objects reflect prevailing 1770s fashion, but most of them have been crudely executed, especially when compared with vessels made at John Bartlam’s pottery in Cain Hoy. The documentary evidence presents a strong case that the products were made by Rudolph Christ, whose intent—that he wanted to take up the manufacture of “white, black, and salt pottery”—was made clear in the report of September 12, 1780, and the 1781 listing of “Ware that has to be made with special care” (see page 85).

The Fineware Pottery in Bethabara, 1786–1789

Any attempt to identify the hand of the potter responsible for the Salem fineware is complicated by all of the “fine” pieces that are attributed, unarguably, to Christ in Bethabara. During the 1966 excavation of the Rudolph Christ waster dump, Stanley South recovered a number of vessel types characteristic of Christ’s production of “fine” pottery at his Bethabara shop. Among them were molded plates in the Queens shape (fig. 20), beakers and mugs (fig. 21), and bowls and deep saucers (fig. 22), many of which were decorated in a simulated tortoiseshell finish. These finewares are significantly different in appearance and finish from the sophisticated forms of sprig-molded wares made in Salem in the early 1780s. The clay body used by Christ at Bethabara is coarser and redder, whereas the fineware clays used in the Salem pottery are whiter and have a much more refined paste. The exceptions are teabowls and saucers made with a white clay (fig. 23) that are nearly identical in form to period creamware examples but covered in an unusually thick brown glaze.

Nothing is more illustrative of the adoption of Staffordshire manufacturing techniques than the use of plaster and clay molds for producing easily repeatable and consistent plates and dishes. We have no specific evidence that Ellis instructed the Moravians in the use of plaster plate molds, but John Bartlam made considerable use of many different rim shapes in his production at Cain Hoy (see Hudgins, “Staffordshire in America,” figs. 14-16). The sizes and shapes of the plate molds used by Christ suggest that they were made from original patterns rather than taken from impressions of imported English examples. He prepared these molds with a variety of edge shapes that paralleled the popular English patterns of the period. The 1781 price list indicates that Christ was making “formed plates and dishes” in Salem at that time (fig. 24). The inventory of the Bethabara enterprise taken on February 1, 1789, records that Christ was bringing back to the Salem pottery “40 plate forms,” suggesting that a sizable number of press-molded plates were made at Bethabara between 1786 and 1789 (fig. 25).

The fragments of the plates recovered at Bethabara reveal the great lengths to which Christ went in order to hide the deficiencies of the coarse red clay body (fig. 26). Intended to simulate British tortoiseshell-decorated creamware, the fronts of the plates are covered in a fine white slip; the backs are covered in a dark manganese slip (fig. 27), a technique reminiscent of the treatment used by contemporary French faience potters (fig. 28).[25] It is not known whether the dark manganese slip was a purposeful appropriation of the French faience style or simply another technique to disguise the poor quality of the Bethabara clay body. Perhaps it was an emulation of the so-called Batavia-style Chinese porcelain, examples of which have been excavated at many American colonial sites.

Christ also added a curious decorative treatment to the backs of the plate and saucer forms made at Bethabara—a simple, beaded roulette embellishment (figs. 29, 30) that does not have parallels on English creamware or French faience; it must have been an inventive use by Christ of the roulette technology.

An uncommon twelve-sided plate mold, made by Christ at Bethabara and dated January 6, 1789, survives, albeit broken and repaired (figs. 31, 32). The shape of the plate is similar to certain British plate patterns of the 1790s (fig. 33), but the series of four small, raised dots at the apex of each facet (fig. 34) seems to be an idiosyncratic addition by Christ. No fragments of bisque or glazed plates taken from this mold have been found in Salem or Bethabara, nor have archaeological parallels been found for the example shown in figure 35, a modified adaptation of the Queens shape with the unusual addition of raised beading along the entire rim and the outside of the plate well.

Why Christ was content to use the imperfect clays at Bethabara for his simulated creamware is a significant mystery. We know that he had some form of white clay at Bethabara from which he prepared his white engobes for the tortoiseshell-decorated wares.[26] It is possible the equipment necessary to wash the clay was part of the Salem pottery and could not be duplicated at the Bethabara pottery during Christ’s relatively short residence.

If the availability of clay was not the issue, perhaps the Bethabara kiln was simply unable to achieve the firing temperatures needed to duplicate the refined earthenwares previously made in Salem. Ellis had been responsible for building a kiln in Salem that could reach those temperatures. Christ might have been unable to replicate the appropriate architecture at Bethabara, or perhaps he was too busy to focus on the construction of a special-purpose kiln. Knowing that Salem’s master potter (Aust) was in poor health, perhaps Christ chose to make do with the production of his simulated tortoiseshell wares until he could return to Salem and its better-equipped pottery.

Return to Salem and the End of the Fineware Pottery

The death in 1789 of Gottfried Aust paved the way for Christ’s return to Salem, now as its master potter. He brought with him, as mentioned before, forty plate molds. Plate fragments archaeologically recovered in Salem show that he had incorporated a variety of shapes in his output, including the Queens shape, the Royal shape, the Feather shape, a bead-and-reel edge treatment, and some other, unclassified neoclassical styles (fig. 36).

The excavated bisque-fired fragments show that a much finer clay body was used in Salem. Although the body was not perfectly white, a very fine engobe was applied to give the plates a much more Staffordshire-like finish (fig. 37), and Christ used a tortoiseshell finish on the front and a green glaze on the reverse (fig. 38). Overall, these plates are far more aesthetically convincing as imitations of Staffordshire products than the examples made at Bethabara; other glazed fragments give the appearance of competence nearly equal to English examples (fig. 39). Unfortunately, despite the large quantities that must have been produced at both Salem and Bethabara, no surviving examples are known.

Christ’s aspirations to create and perfect Staffordshire-like ceramics continued after he became master of the Salem pottery, even though he was overwhelmed with orders for the coarse utilitarian wares. One Salem creamware plate fragment, hand-painted under the glaze with manganese in a chinoiserie style, shows that such decorated wares were part of the pottery’s output (fig. 40). Fragments from a small creamware punch bowl also show hand-painted chinoiserie decoration, in combination with neoclassical swags (fig. 41). Both examples must date to the 1790s.

When faience potter Carl Eisenberg arrived in 1793, press-molded plates were still being produced in the Salem pottery.[27] Small fragments from a Queens-shape plate (fig. 42) show an intriguing use of faience to mimic the widespread British pearlware exports of the 1790s. This collaboration between Christ and Eisenberg suggests that innovation was alive and well in the Salem pottery, even though there was continuing demand for the coarse redwares.

Further innovation is evidenced in Christ’s experimentation with stoneware about 1793. By 1795 he had shown members of the Collegium samples of stoneware from a firing of the material.[28] South’s excavations recovered saggar fragments covered with a salt glaze that he associated with the 1795 firing. As discussed in this volume by Luke Beckerdite and Johanna Brown (“Eighteenth-Century Earthenware from North Carolina: The Moravian Tradition Reconsidered”), quantities of salt as a glazing ingredient show up on the pottery inventories until 1809. It is hoped that future investigations will clarify what stoneware products were produced.

Many intriguing issues await further research, including an analysis of clays and glazes, which is under way. One provocative artifact is a fragmentary blackware teapot with a molded crabstock handle (fig. 43). This object is imitative of the English Jackfield wares, popular from the 1760s into the 1780s. “Black” pottery is articulated in the September 1780 record of Christ’s intentions to manufacture “white, black, and salt pottery.” Recovered among the sherds of “white” and “salt” pottery in the Lot 49 waster pit, this fragmentary object attests that Christ’s intentions are manifest in tangible products.

In 1797 Christ announced a twenty-foot expansion of the Salem pottery building. The addition was probably constructed in 1798, sealing the waster pit.[29] The large fragments of nearly complete ceramics suggest that it was filled in a relatively short period of time, not over a matter of years—perhaps when Christ was preparing to reorganize the shop. If some of these objects are indeed the products of William Ellis and his 1774 trials of queensware and stoneware, they must have been curated by Aust and Christ on the shelves of the pottery even in waster form and finally discarded during the shop expansion.

The exciting story of William Ellis’s introduction of Staffordshire-style ceramics into the Salem and Bethabara potteries will benefit from future archaeological investigations of Lot 48 and the full excavation of Ellis’s experimental kiln. We are fortunate that the extremely detailed records of the Moravian community, combined with the amazing objects recovered in Stanley South’s painstaking archaeological excavations, have preserved this unique chapter of American ceramics history.

Stanley A. South, The Search for John Bartlam at Cain Hoy: American’s First Creamware Potter, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology Research Manuscript Series 219 (Columbia: University of South Carolina, 1993); Bradford L. Rauschenberg, “John Bartlam, Who Established ‘new Pottworks in South Carolina’ and Became the First Successful Creamware Potter in America,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 17, no. 2 (November 1991): 1–66; Robert Hunter, “John Bartlam: America’s First Porcelain Manufacturer,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Hunter (Easthampton, Mass.: Antique Collectors’ Club for the Chipstone Foundation, 2007), pp. 193–96.

For more on the Moravians’ motivations in expanding the line of ware produced at the Salem pottery, see Frederic William Marshall, report to the Aeltesten Conferenz, May 5, 1774, as quoted in Bradford L. Rauschenberg, “Escape from Bartlam: The History of William Ellis of Hanley,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 17, no. 2 (November 1991): 88.

Stanley South, Historical Archaeology in Wachovia: Excavating Eighteenth-Century Bethabara and Moravian Pottery (New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 1999), pp. 325–67.

Rauschenberg, “Escape from Bartlam,” pp. 80–102.

Ibid.

Minutes of the Aufseher Collegium, December 8, 1773, as quoted in ibid., p. 84.

John Bivins Jr., The Moravian Potters in North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for Old Salem, Inc., 1972), pp. 30–35.

Frederic William Marshall’s report of January 1, 1774, gives evidence of this first exposure to British-style earthenwares: “the English Fabrique of Queensware and Tourtoise Shell” from an unknown individual who clearly was associated with John Bartlam. Rauschenberg (“Escape from Bartlam,” p. 87) speculates that this individual might have been Bartlam himself, between the time he closed his Charleston factory in 1771 and opened his Camden pottworks in 1774.

See South, Historical Archaeology in Wachovia, p. 259, fig. 26.37.

Minutes of the Aufseher Collegium, February 26, 1774, as quoted in Rauschenberg, “Escape from Bartlam,” p. 87.

Inventory of the Salem Pottery, April 1774, translated and transcribed under Pottery Inventories, Old Salem Research Files, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

David Barker, “‘The Usual Classes of Useful Articles’: Staffordshire Ceramics Reconsidered,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 72–93 (emphasis added).

Frederic William Marshall, report to the Aeltesten Conferenz, May 5, 1774.

Minutes of the Aufseher Collegium, January 27, 1779, as quoted in Rauschenberg, “Escape from Bartlam,” p. 90.

Minutes of the Aufseher Collegium, September 12, 1780, as quoted in ibid., pp. 91–92.

Bivins, Moravian Potters in North Carolina, pp. 31–33.

A complete transcript of this contract is in Rauschenberg, “Escape from Bartlam,” pp. 96–97, and contains several important points to understanding Christ’s territorial claim to the fineware.

This list, as recorded by the Aufseher Collegium, December 11, 1781, is reproduced in South, Historical Archaeology in Wachovia, p. 275.

Ibid., p. 333.

Bivins, Moravian Potters in North Carolina, pp. 165–66.

Rauschenberg, “Escape from Bartlam,” p. 89.

T. Townsend Walford and Roger Massey, eds., Creamware and Pearlware Re-examined (Beckenham, Kent: English Ceramic Circle, 2007). Special thanks to Troy Chappell, who reviewed the evidence for the date origins of extruded twisted handles on creamware forms.

See George L. Miller and Robert Hunter, “How Creamware Got the Blues: The Origins of China Glaze and Pearlware,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 135–61, fig. 24.

One reference made demonstrates that Staffordshire-style wares were “made by hand on the potter’s bench, instead of with instruments on the potter’s wheel.” South, Historical Archaeology in Wachovia, p. 272. South’s interpretation of this passage is that the bench was the place for molding and casting, but it could also include lathe turning.

French faience plates and dishes were available in colonial America and have been excavated in Williamsburg as well as in French settlements along the Mississippi. See, for example, www.sangamoarchaeology.org/FrenchFaience.html (accessed July 9, 2009).

“3 loads of white clay from Bethabara,” quoted in South, Historical Archaeology in Wachovia, p. 279, Table 27.3.

See in this volume Luke Beckerdite and Johanna Brown, “Eighteenth-Century Earthenware from North Carolina: The Moravian Tradition Reconsidered,” and Robert Hunter and Michelle Erickson, “Making a Moravian Faience Ring Bottle.”

Minutes of the Aufseher Collegium, November 3, 1795, transcribed and filed under Lot 48, Old Salem Research Files, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

See South’s discussion of the archaeological remains of this structure in South, Historical Archaeology in Wachovia, p. 334.