Mug, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Bisque-fired earthenware. H. 5 7/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens; unless otherwise noted, photos by Gavin Ashworth.)

Mug, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1770–1780. Creamware. H. 5 3/16". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Sprig mold, Salem, North Carolina, ca. 1780. High-fired clay. L. 2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The back of this mold bears the initials “RC” for Rudolph Christ. This is the only surviving sprig mold from the Salem pottery.

Detail of the base of the mug illustrated in fig. 1. The use of a roulette to finish the foot in this manner is very unusual and has not been seen on any Staffordshire examples or on any of the creamwares produced by John Bartlam at Cain Hoy.

An assortment of roulettes and related trimming tools used by present-day potter Don Carpentier in the manufacture of British-style creamwares and pearlwares. (Courtesy, Don Carpentier.)

Mug fragment adhered to kiln prop, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Mug fragments, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) These fragments show the fluted gadrooned rouletting seen on the mug illustrated in fig. 1.

Teapot, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Lead-glazed earthenware. L. 7". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) It is unclear whether this example, one of the most important ceramic objects of eighteenth-century America, was produced by William Ellis during his 1774 visit to the Salem pottery or was a later creation of Rudolph Christ.

View of the opposite side of the teapot illustrated in fig. 8.

Detail of the base of the teapot illustrated in figs. 8 and 9.

Teapot spout, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Handled cup fragments, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The sprigging on the handle terminals, which matches that on the terminals of the teapot illustrated in fig. 8, and the tortoiseshell glaze on the teapot and the matching saucer shown in fig. 13 show that these teawares were being manufactured in sets.

Saucer fragment, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Mug or coffee cup, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Mug or teacup, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The chevron roulette shown along the rim of this vessel and other fragments is a detail often seen on British white salt-glazed teawares.

Mug or teacup fragment, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

“Fineware” fragments, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Mug fragment, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The lines on this straight-sided tankard appear to be the result of turning on the lathe, to simulate a style of creamware popular in the 1770s.

“Fineware” fragments, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Bisque-fired and lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

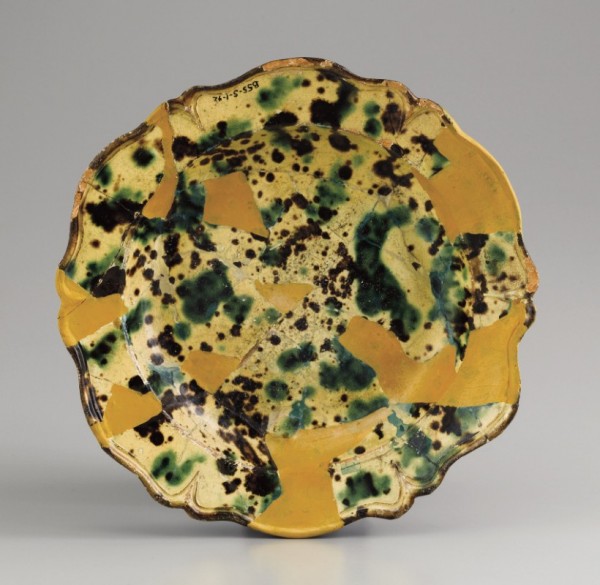

Plate, attributed to Rudolph Christ, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1786–1789. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 9 5/8". (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Beaker and mug, attributed to Rudolph Christ, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1786–1789. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. of mug 4". (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Saucer dish and bowl, attributed to Rudolph Christ, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1786–1789. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. of bowl 7 5/8". (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Teabowls and saucer, attributed to Rudolph Christ, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1786–1789. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. of teabowl 3 3/8". (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Plate mold, attributed to Rudolph Christ, Salem or Bethabara, North Carolina, 1781–1789. Plaster. D. 10". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

Plate, attributed to Rudolph Christ, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1786– 1789. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 9 3/4". (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Detail of the edge of the plate illustrated in fig. 25 showing the red clay body beneath the white slip.

Detail of the reverse of the plate illustrated in fig. 25. Note the two parallel bands of beaded roulette.

Dish, Rouen, France, 1780. Tin-glazed earthenware. L. 16 3/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Saucer fragment, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Saucer fragment, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Plate mold, Rudolph Christ, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1789. Plaster. D. 10 7/8". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

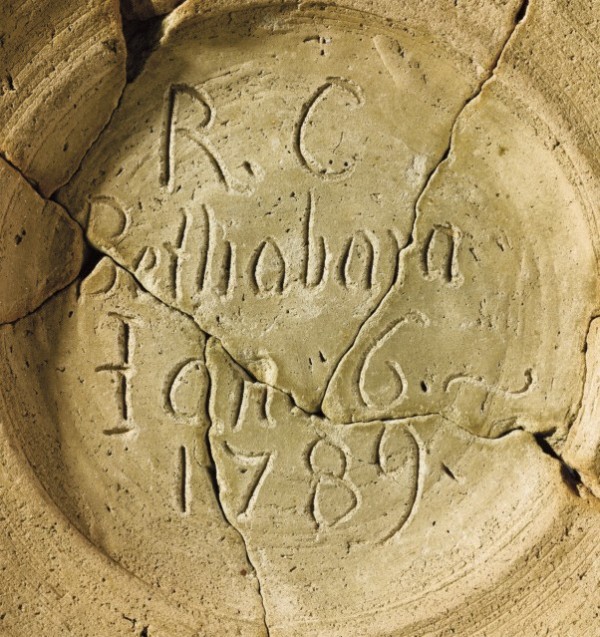

Detail of the inscription on the plate mold illustrated in fig. 31: “R. C / Bethabara / Jan. 6.~ / 1789.”

Plate, probably Staffordshire, ca. 1790. China glaze. D. 10". (Private collection.) This English example of a twelve-sided plate is very similar to the plate mold illustrated in fig. 31.

Detail of the plate mold illustrated in fig. 31.

Plate mold, attributed to Rudolph Christ, Salem or Bethabara, North Carolina, 1786–1789. High-fired clay. D. 8 5/8". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

Plate fragments, Salem, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The rim fragment on the left has the bead-and-reel pattern often used on English white salt-glazed plates. The center example is the popular feather-edge pattern used exclusively on English creamware. The fragment on the right shows fine swags in a neoclassical pattern similar to those used on English pearlware and creamware plates.

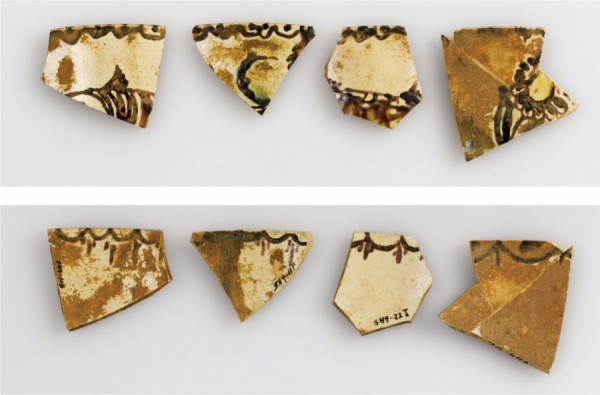

Plate fragments (obverse and reverse), Salem, North Carolina, 1780–1786. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) Note the use of roulette decoration on the reverse of the left fragment.

Plate fragments, Salem, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Plate fragments, Salem, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Plate fragment, Salem, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) This plate fragment has hand-painted manganese decoration imitative of the chinoiserie decoration popular on late-eighteenth-century British creamware and pearlware.

Bowl fragments, Salem, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) These fragments show the exterior (top) and interior (bottom) of a small creamware punch bowl. The manganese decoration is also in the chinoiserie style.

Plate fragments, Salem, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) These fragments from a Queens-shape plate were decorated with cobalt on a pale blue faience glaze, in a style reflecting contemporary English china-glazed wares.

Teapot fragments, Salem, North Carolina, 1774–1786. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The teapot was probably made during William Ellis’s tenure at the Salem pottery, ca. 1774.